What is achalasia

Achalasia from the Greek for ‘does not relax’, also known as cardiospasm, is a neurodegenerative motility disorder of the esophagus resulting in deranged esophageal peristalsis and loss of lower esophageal sphincter function 1. Instead of food and drink moving normally through the esophagus when you swallow, in people with achalasia they can get stuck there, or even come back up into the mouth.

Under normal circumstances, when you swallow, food passes down the esophagus by waves of muscle contractions and through a special valve into the stomach.

The valve – a ring of muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (see Figures 2 and 3)– controls the entry of food from the lower end of the esophagus into the stomach. If you have achalasia, the nerves that control this sphincter are affected, preventing it from relaxing and allowing food to pass through.

Achalasia also affects the muscular contractions of the esophagus (peristalsis), which normally work to propel food down towards the stomach. This is thought to be due to a malfunction of the nerves around the esophagus.

The pathogenesis of achalasia is not well understood but it is believed to be due to an inflammatory neurodegenerative insult with possible viral involvement. The measles and herpes viruses have been suggested as candidate viruses however molecular techniques have failed to confirm these claims and therefore the causative agent remains undiscovered 2. Genetic and autoimmune components have also been suggested as origins of the neuronal damage however research to date has not found the exact cause 3. Inflammatory changes within the esophagus following the causative insult result in the loss of postganglionic inhibitory neurons in the myenteric plexus and a consequent reduction in the inhibitory transmitters, nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide. The excitatory neurons remain unaffected, with the resulting imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons preventing lower esophageal sphincter relaxation 4. Lack of peristalsis and a non-relaxing lower esophageal sphincter cause progressive dysphagia. Regurgitation, particularly at night, with aspiration of undigested food and weight loss can be presenting features, particularly in established disease. Features which present in the early stages of the disease may be similar to that of gastro-esophageal reflux (GERD), including retrosternal chest pain typically after eating and heartburn 5. Due to initial non-specific symptoms in early stage disease and the low prevalence of achalasia worldwide, the condition often goes undiagnosed for many years, giving rise to features of late stage disease and their associated complications.

Historically, annual achalasia incidence rates were believed to be low, approximately 0.5-1.2 per 100000. More recent reports suggest that annual incidence rates have risen to 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations. Achalasia affects men and women equally between the ages of 30-60. It can also occur in infancy and childhood.

The cause of achalasia is still unknown (idiopathic), but is likely to be multi-factorial. Suggested causes include environmental or viral exposures resulting in inflammation of the esophageal myenteric plexus, which elicits an autoimmune response 1. However, Achalasia can also develop as a result of damage to the nerves to the esophagus. This is seen in chronic Chagas disease – a condition common in South America which is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite.

Achalasia can happen at any age, but is more common in middle-aged or older adults. While there is no cure currently available, there are treatments that can help manage the symptoms.

Achalasia is a progressive disease meaning patients will gradually develop increasing severity of difficulty when swallowing. Medical treatment may alleviate symptoms but they do not provide a long term solution.

Most patients require surgical intervention. Those who are treated early (before marked dilation) may avoid complications of esophageal ulceration, esophageal candidiasis and aspirating stomach contents into the lung. There is also a slight increase in the risk of esophageal carcinoma (cancer of the esophagus). There are limited data to support routine screening for cancer. The overall number of cancers remains low and estimates have suggested that over 400 endoscopies would be required to detect one cancer 6. These numbers are further tempered by the fact that the survival of these patients is poor once the diagnosis is made 7.

With successful myotomy (surgery dividing the abnormal muscle in the lower sphincter of the esophagus), patients are able to gain weight and lead a normal life. Some will develop gastro-esophageal reflux (GERD), especially after surgery which responds to medical treatment. Some recommend endoscopic monitoring for the increased risk of esophageal carcinoma.

Figure 1. Esophagus

Figure 2. Lower esophageal sphincter

Figure 3. lower esophageal sphincter (endoscopic view)

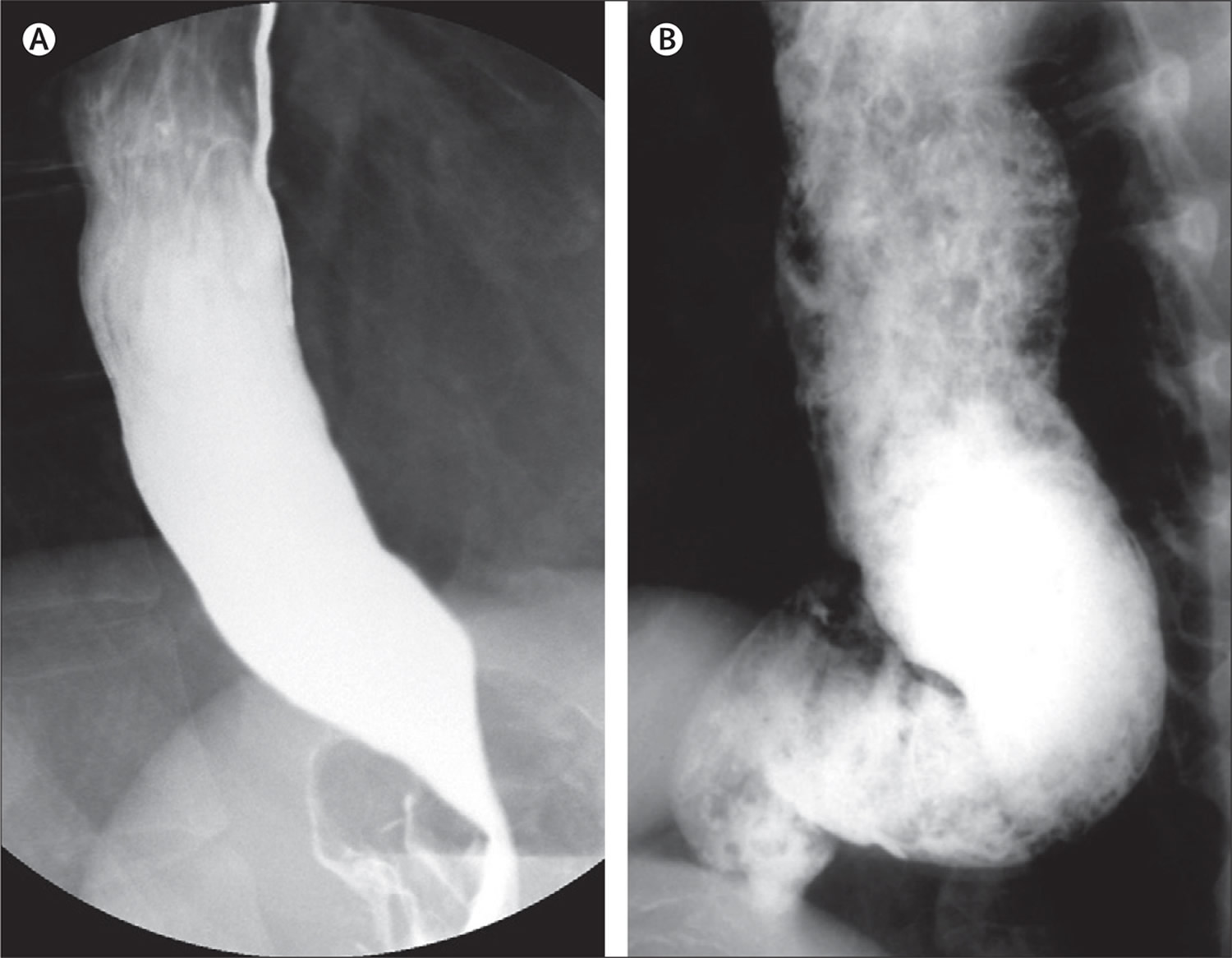

Figure 4. Esophageal achalasia (Barium swallow)

Note: Barium swallow demonstrating typical “bird’s-beak” appearance of the lower oesophageal sphincter in achalasia. The oesophagus above this is dilated.

Achalasia types

The use of high-resolution manometry has led to the subclassification of achalasia into three clinically relevant groups on the basis of the pattern of contractility in the oesophageal body 8 or variants with potential treatment outcome implications 9. To date, three separate retrospective cohort studies have shown that subtype II has the best prognosis, whereas subtype I is somewhat lower and subtype III can be difficult to treat 9. Although these subtypes can be defined with careful analysis of conventional tracings, it is easier and more reproducible with high-resolution manometry.

On the basis of the information reported to date, the evidence clearly confirms that the subtype of achalasia is an independent predictor of success, with type III having the worst outcome after therapy. To what extent the subtypes represent different phenotypes or simply reflect different stages of the disease is hard to say. Recent detailed analyses of high-resolution manometry tracings, combined with impedance and ultrasound images, seem to suggest that type III and type I achalasia, respectively, represent the feature of a compensated and decompensated esophagus to outflow obstructions caused by a dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter 10. The pressurization pattern typical of type II achalasia, on the other hand, stems from another, novel motor response of the esophagus involving longitudinal muscle contractions of the distal esophagus.

Be that as it may, it seems fair to conclude that type III achalasia, characterized by well-defined, lumen-obliterating spastic contractions in the distal esophagus, responds the least to therapy. In this subgroup of achalasia patients, reducing the lower esophageal sphincter pressure may not suffice to control the symptoms, especially as the segment affected by the spastic motility extends well above the lower esophageal sphincter. Chest pain, a prominent symptom in type III achalasia patients (probably associated with spastic contractions), is especially difficult to treat, explaining the lower success rates in these patients. The response to therapy in type II is rather better than that in type I, but in the European Achalasia Trial, at least there were apparently no major differences in the success rate for these subtypes between pneumatic dilation and laparoscopic Heller myotomy.

Future outcome studies are needed to determine the clinical impact of the three subtypes 11.

- Type I (classical achalasia; no evidence of pressurisation) achalasia is associated with absent peristalsis and minimal esophageal body pressurization.

- Type II achalasia is associated with intermittent periods of panesophageal pressurization related to a compression effect.

- Type III achalasia has evidence of abnormal contractility (spastic) with premature or spastic distal esophageal contractions.

Table 1. Subtypes of achalasia manometric, clinical, and histologic differences

| Achalasia Subtype | Manometric Findings | Clinical Findings | Histologic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Elevated median IRP (>15 mm Hg) 100% failed peristalsis (DCI <100 mm Hg/s/cm) | Increased aganglionosis and neuronal loss | |

| II | Elevated median IRP (>15 mm Hg) Panesophageal pressurization ≥20% of swallows | Most likely to report weight loss | Increased aganglionosis and neuronal loss |

| III | Elevated median IRP (>15 mm Hg) Premature contractions ≥20% swallows with DCI >450 mm Hg/s/cm | Least likely to report weight loss More likely to report chest pain | Preserved ganglion cells |

Abbreviations: DCI = distal contractile integral; IRP = integrated relaxation pressure

[Source 12 ]Figure 5. Manometric types of achalasia

Note: Type I is characterised by absence of distal pressurisation to greater than 30 mm Hg. In type II, pressurisation to greater than 30 mm Hg occurs in at least two of ten test swallows, whereas patients with type III disease have spastic contractions with or without periods of compartmentalized pressurisation.

[Source 13Prognosis of achalasia

Surgery often results in longer lasting relief of symptoms, while dilation alone (done at endoscopy) often results in only temporary improvement in symptoms. There is a slightly increased risk of esophageal cancer.

Complications of achalasia

Many people with achalasia delay going to the doctor and getting a diagnosis because their symptoms are not causing major discomfort. However, if you think you may have achalasia, it’s important that you seek medical advice and treatment, because doctors believe the condition may slightly increase the risk of cancer of the esophagus.

Other complications of achalasia can arise because of undigested food being regurgitated during sleep. If the food is accidentally inhaled into the lungs, this can lead to pneumonia, an abscess of the lung, or damage to the bronchial tubes.

Achalasia can also lead to inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis).

Achalasia causes

The causes of achalasia are not well understood. Often when someone develops the disorder, there is no obvious reason why the nerves in their esophagus no longer work properly.

Suspected possible causes of achalasia include:

- viral infections that damage the nerves of the esophagus (this may happen earlier in life, rather than at the time of developing achalasia)

- autoimmune conditions (when the immune system attacks the body’s own cells)

- Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi) – an infectious disease that can destroy nerve cells 14.

Some people seem to be more susceptible to developing achalasia, including people with Parkinson’s disease.

There has been much debate over the cause of achalasia, with several potential triggers for the inflammatory destruction of inhibitory neurons in the oesophageal myenteric plexus being implicated. These include autoimmune responses, infectious agents and genetic factors.

Auto-immune conditions

One recent study observed that patients with achalasia were 3.6 times more likely to suffer an autoimmune condition, compared with the general population 15. Sjogren’s syndrome, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and uveitis were all significantly more prevalent in achalasia patients. The study also found the presence of a T-cell (T lymphocyte) infiltrate and antibodies within the myenteric plexus of many patients with achalasia and an increased presence of human leukocyte antigen class II antigens 15. Another study noted an overall higher prevalence of neural autoantibodies in patients with achalasia in comparison with a healthy control group 16. Although no specific autoantibody was identified, this further supports the theory that achalasia has an autoimmune basis 16.

Infectious agents

The role of an infectious agent in the development of achalasia has been widely debated with several viral agents being implicated. For example, Chagas disease has a known infectious aetiology, and exhibits many similarities with achalasia 14. In addition, there are several reports of varicella zoster virus and Guillain-Barre syndrome preceding the onset of achalasia 14. Antibody studies have demonstrated increased titres to herpes and measles viruses in patients with achalasia in comparison to healthy control groups 17. One study looking specifically at the link between the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and primary achalasia indicated the presence of HSV-1 reactive immune cells in the lower oeseophageal sphincter of achalasia patients, suggesting that HSV-1 may be involved in the neuronal damage to the myenteric plexus leading to achalasia 18. A further study of peripheral blood immune cells found that patients with achalasia showed an enhanced response to HSV-1 antigens 19. In contrast, another investigation using PCR on myotomy specimens did not find any association between herpes, measles or human papilloma viruses and achalasia 20. The current evidence for a causative infectious agent is contradictory and no clear causal relationship has yet been established.

Genetic predisposition

The genetic basis for achalasia has not been widely investigated due to its low prevalence. One syndrome, known as the triple “A” syndrome, which consists of a triad of achalasia, alacrima and adrenocorticotrophic hormone resistant adrenal insufficiency is a known autosomal recessive disorder caused by gene mutations on chromosome 12. This syndrome, together with the prevalence of cases within children of consanguineous couples 21, suggests the possibility for a genetic component to the aetiology of achalasia. There have been associations with other genetic diseases including Parkinson’s disease, Downs syndrome and MEN2B syndrome 22. One recent suggested the possibility of involvement of the rearranged during transfection gene, which is a major susceptibility gene for Hirschprung’s disease (also linked with Down’s syndrome) 23. Mayberry et al 24 conducted a study of first degree relatives of achalasia patients but concluded that inheritance was unlikely to be a significant causative factor due to the rarity of familial cases and exposure to common environmental and social factors within a family group may explain the presence of familial cases of achalasia.

It has been postulated that achalasia may incorporate a multi-factorial aetiology with an initiating event such as a viral or environmental insult resulting in oesophageal myenteric plexus inflammation. This inflammatory reaction may then initiate an autoimmune response in a susceptible group of genetically predisposed people, causing destruction of inhibitory neurons 25.

Achalasia symptoms

The symptoms of achalasia often start slowly and progress gradually, sometimes taking years to fully develop. Achalasia signs and symptoms may include 12:

- difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), which may feel like food or drink is stuck in your throat and can be painful ~ 82%-100%

- a lump or feeling of fullness in the throat

- chest pain that comes and goes ~ 25%-64%

- heartburn, which often leads to misdiagnosis of achalasia as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) ~ 27%-42% 26

- regurgitation of undigested food or liquids (including when asleep) ~ 76%-91%

- coughing or choking (due to regurgitation of food), which may be worse at night ~ 37%

- hiccups

- difficulty burping

- belching

- vomiting

- weight loss ~ 35%-91%

- pneumonia (from aspiration of food into the lungs) ~ 8%

The most frequently occurring symptoms of achalasia are dysphagia (>90%) for solids and liquids, regurgitation of undigested food (76–91%), respiratory complications (nocturnal cough [30%] and aspiration [8%]), chest pain (25–64%), heartburn (18–52%), and weight loss (35–91%) 27.

Heartburn can lead to an erroneous diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), which might culminate in antireflux surgery. Nocturnal coughing mainly occurs in patients with substantial stasis of large amounts of food and secretions. Chest pain is predominantly present in patients with type III disease 28 and responds less well to treatment than do dysphagia and regurgitation, which probably explains the less favourable therapeutic results obtained in patients with type III disease compared with those with type I or II disease 29. However, symptoms of achalasia are not specific, which explains the long delay between onset of symptoms and the final diagnosis (up to 5 years in some studies) 30. Although some patients lose a lot of weight (more than 20 kg), achalasia should also be considered in obese patients 31.

Table 2. Eckardt Score for Clinical Classification of Achalasia Severity

| Eckardt Score | Dysphagia | Regurgitation | Retrosternal pain (chest pain) | Weight loss (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None | None | None |

| 1 | Occasional | Occasional | Occasional | < 5 |

| 2 | Daily | Daily | Daily | 05/10/21 |

| 3 | Each meal | Each meal | Each meal | > 10 |

Achalasia diagnosis

Achalasia can be diagnosed in a number of ways. If your doctor thinks you may have achalasia, you will be referred to a hospital where a specialist called a gastroenterologist may do one or more of the following diagnostic tests. Achalasia can be diagnosed based on high-resolution esophageal manometry, esophagography (X-rays of your upper digestive system) or endoscopy findings 32.

- Barium swallow. The ‘barium swallow’ is a common test for achalasia. This involves drinking a thick liquid containing the chemical barium, which coats the inside of your esophagus and stomach, making them show up on an X-ray. In people with achalasia, the test often shows that the lower part of the esophagus has narrowed, while an area above this has become stretched or enlarged. The specialist will also be able to see whether the muscle contractions of the esophagus (peristalsis) are working normally or not.

- Gastrografin swallow. A Gastrografin swallow is similar to a barium swallow – you have to swallow a liquid which contains an X-ray contrast medium – this shows up on X-ray and shows the esophagus, including the outline of the inside of the esophagus. Gastrografin is often used when a barium meal can’t be used. Gastrografin is less irritating to the body if there is a leak from the esophagus, such as from a tear.

- Esophageal Manometry. Another investigation that can be used in the diagnosis of achalasia is esophageal manometry. Esophageal manometry is essential for assessing esophageal motor function in patients with achalasia 32. In this test, a thin tube with pressure gauges along its surface is inserted through the mouth or nose into the esophagus. As you swallow small sips of water, the instrument measures the pressure along your esophagus. In a person with achalasia, the test usually shows that the muscular contractions needed to pass food along the esophagus are weak or missing, and that the lower esophageal sphincter is not relaxing as it should after you swallow. The sphincter may also have higher than normal pressure. Manometric findings of aperistalsis and incomplete lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation without evidence of mechanical obstruction supports the diagnosis of achalasia 33. Other findings, such as increased basal lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and baseline esophageal body pressure with simultaneous non-propagating contractions, are also suggestive of achalasia, but are not required for its diagnosis. Though rare, variants of achalasia differing in the degree of incomplete lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation and aperistalsis, as well as some characterized by complete lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation, have been described 11. Aperistalsis has been defined as a lack of esophageal body peristalsis and can present with different pressure patterns, such as a “quiescent” esophageal body, isobaric panesophageal pressurization, and simultaneous contractions. Achalasia variants presenting with propagating contractions, which could represent either early achalasia or, most commonly, a subclinical mechanical obstruction at the esophago-gastric junction, have also been described. This heterogeneity demonstrates the need for motility studies, where motor patterns can affect diagnosis and management 33.

- Endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]). An endoscope (a flexible tube with a light and camera on the end) can be used to examine the esophagus. If you have achalasia, this may show that the esophagus is wider than normal. It would also show if there were any obstructions in the esophagus or stomach. During the test, the specialist may take a sample of tissue (a biopsy) from your esophagus or stomach to examine in the laboratory for any abnormalities.

Every patient with clinical suspicion of achalasia should undergo an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to evaluate for pseudoachalasia 12. A barium swallow is useful for assessing esophageal morphology and motility, and at times is the test in which the diagnosis of achalasia is initially suspected. However, endoscopic and radiologic studies alone may identify only up to 50% of achalasia; thus, the gold standard diagnostic test is high-resolution manometry, which can classify achalasia into its 3 subtypes 32.

Barium esophagography (barium swallow) and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) are used as complementary tests to manometry in the diagnosis and management of achalasia 34. However, neither esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) nor barium esophagography (barium swallow) alone is sensitive enough to achieve a definitive diagnosis 33. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) can be used as a supportive tool for diagnosis of achalasia in only one-third of patients, and esophagography in up to two-thirds of patients 33. Thus, patients suspected to have achalasia but who have shown normal results in EGD or esophagography studies must undergo esophageal motility tests. However, in patients with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or esophagography findings typical of achalasia, esophageal motility tests should be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Achalasia treatment

Achalasia is treated by a gastroenterologist, who deals with problems of the digestive tract. Specific treatment depends on your age, health condition and the severity of the achalasia. However, there is no specific therapy targeting the underlying disease process, because the pathogenesis of the impaired esophageal peristalsis and poor esophageal sphincter relaxation are unclear.

While treatments can’t repair damaged nerves or restore normal contractions in the esophagus, they can often improve the symptoms of achalasia. They do this by weakening the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) at the base of the esophagus, so that food is able to pass through to the stomach.

Pneumatic balloon dilation, peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and laparoscopic Heller myotomy provide similarly effective long-term results for esophageal achalasia. In patients whose condition is too poor for endoscopic treatment or surgery, botulinum injection or oral medication might be helpful.

Balloon dilation

Often one of the first approaches used to treat achalasia is dilation or stretching of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) at the base of the esophagus 35. This is done by putting a small balloon inside the sphincter and inflating it.

Treatment parameters such as balloon size, number of dilations, inflation pressure, and duration vary according to the specialists or institutions. Depending on the general condition of the patient, graded pneumatic balloon dilation (with 30-mm, 35-mm, or 40-mm balloons) is considered one of the primary options for achalasia 36. A prospective randomized European study of pneumatic balloon dilation and laparoscopic Heller myotomy reported that the therapeutic success rate was not significantly different between the 1- and 2-year follow-ups 37. Also, there was no significant difference in the pressure at the LES or esophageal emptying, as assessed by the height of the barium column 35.

Unfortunately, there is a risk during this procedure that the esophagus can rupture or tear. The dilation process may also need to be repeated, as it can stop having the desired effect after a while, and this further increases the risk of rupture.

According to a retrospective analysis of 209 patients, management of achalasia with initial dilation can provide good or excellent long-term results and high patient satisfaction rates 38. However, outpatient procedure may need to be repeated if the esophageal sphincter doesn’t stay open. Nearly one-third of people treated with balloon dilation need repeat treatment within six years.

Figure 6. Balloon (pneumatic) dilation

Note: Schematic representation of the pneumodilatation procedure. The deflated balloon is inserted over a guide wire, after which the slightly inflated balloon is positioned at the oesophagogastric junction with the indentation still visible. Finally, the balloon is fully inflated and the indentation disappears. After removal of the balloon, the LOS is distended, allowing adequate passage. LOS=lower oesophageal splinter.

Medications

There are no medicines in US to specifically treat achalasia, although sometimes medicines may be prescribed to help relax the lower esophageal sphincter. These include nitroglycerin (such as glyceryl trinitrate) and calcium channel blockers (such as nifedipine), which are also used to treat high blood pressure and angina. Your doctor might suggest muscle relaxants such as nitroglycerin (Nitrostat) or nifedipine (Procardia) before eating.

Medications are generally considered only if you’re not a candidate for pneumatic balloon dilation or surgery, and Botox hasn’t helped. This type of therapy is rarely indicated.

While these medications may help relieve some of the symptoms of achalasia temporarily, they are not effective in all cases, and tend to stop working over time. They can also cause unwanted side effects such as headaches and low blood pressure. For these reasons, they are often only used for people who are unable to have other forms of treatment.

Botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin (Botox) is a nerve toxin that is well-known for its ability to relax muscles, including those causing facial frown lines and wrinkles. When used in the treatment of achalasia, Botulinum toxin is injected directly into the lower esophageal sphincter via an endoscope. Although the procedure is relatively safe, it only provides temporary relief (usually for 3 to 12 months) and its long-term effects are not yet known 39. The median duration of the symptom-free period was 11.5 months after the first botulinum injection, and 10.5 months after the second 40.

Repeat Botulinum toxin injections may make it more difficult to perform surgery later if needed. Botox (botulinum toxin type A) is generally recommended only for people who aren’t good candidates for pneumatic dilation or surgery due to age or overall health.

Typically, 100 U of botulinum toxin is injected into 4 quadrant of lower esophageal splinter (LES) each as 4 divided doses. There is wide variability in the timing of the botulinum toxin injections. A multicenter randomized study found no clear dose-response effect (doses of 50, 100, or 200 U) after 1 month, but 2 injections of 100 U botulinum toxin, 30 days apart, was the most effective therapeutic schedule 41. According to a 9-year retrospective chart review, botulinum toxin was used in 21.0% of achalasia patients. Symptom improvement persisted for a mean of 6.2 months, with a need for repeated injections (mean, 1.7; range: 1-7), and about 43.0% of patients required different, additional treatments 42.

Botulinum toxin injection can induce esophageal perforation or, inflammatory mediastinitis 43 and chest pain (4.3%) or heartburn (0.7%) 44, but it is a relatively safe treatment because of the low probability of complications. Botulinum toxin injection is less efficacious than pneumatic balloon dilation and myotomy in inducing long-term remission of achalasia 40. However, if myotomy or pneumatic balloon dilation cannot be performed because the patient is in poor general condition, repeated botulinum toxin injection should be considered. Following repeated botulinum toxin injection, 50.0% of patients were asymptomatic.

Achalasia surgery

Surgery may be recommended for younger people because nonsurgical treatment tends to be less effective in this group.

Surgical options include:

Heller myotomy

Surgery can be done to decrease the pressure in the lower sphincter of the esophagus, using a procedure called myotomy (or Heller myotomy). This type of surgery is generally reserved for cases where achalasia does not respond to treatment using balloon dilation. During the myotomy, the surgeon cuts the lower esophageal sphincter muscle to release the tension. The surgery is done laparoscopically (using small abdominal incisions to pass a camera and surgical instruments through) and under a general anesthetic.

Although the operation is successful in about 85 per cent of cases, up to 20 per cent of people develop a condition called gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) after surgery, which causes acid in the stomach to rise into the esophagus and can cause heartburn.

To avoid future problems with GERD (gastro-esophageal reflux disease), a procedure known as fundoplication might be performed at the same time as a Heller myotomy. In fundoplication, the surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the lower esophagus to create an anti-reflux valve, preventing acid from coming back (GERD) into the esophagus. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure.

Fundoplication

The surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the lower esophageal sphincter, to tighten the muscle and prevent acid reflux. Fundoplication might be performed at the same time as Heller myotomy, to avoid future problems with acid reflux. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure.

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)

A new operation known as peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) has recently been developed, however, long-term follow-up studies are required to define the role of POEM in the initial endoscopic treatment of achalasia 33. Previous meta-analyses of POEM showed a clinical success rate of 98% 45. Additionally, in another meta-analysis, the postoperative Eckardt score was better for patients who underwent POEM versus those who underwent Heller myotomy 46. Recent guidelines for achalasia stated that peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) has an efficacy similar to that of Heller myotomy 47. A study with a 3-year follow-up showed that POEM (peroral endoscopic myotomy) was comparable to Heller myotomy in terms of the postoperative Eckardt score and quality of life 48. A large, recently published large cohort study, with long-term follow-up, showed that the clinical success rate of POEM was 87% after a median follow-up of 49 months 49.

In the POEM procedure, the surgeon uses an endoscope inserted through your mouth and down your throat to create an incision in the inside lining of your esophagus. Then, as in a Heller myotomy, the surgeon cuts the muscle at the lower end of the esophageal sphincter. However, in contrast to Heller myotomy, which requires partial fundoplication to reduce pathologic acid reflux, POEM is typically performed without any anti-reflux procedure 50.

POEM may also be combined with or followed by later fundoplication to help prevent gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). Some patients who have a POEM and develop gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) after the procedure are treated with daily oral medication.

Previous meta-analyses reported that acid reflux occurs more frequently after POEM than after Heller myotomy 51. However, there was no difference in the rate of reflux symptoms, pathologic acid reflux, or the requirement for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) between the POEM and Heller myotomy groups 52.

Management of achalasia recurrence after initial treatment

If pneumatic balloon dilation fails as a first-line treatment, additional treatment with pneumatic balloon dilation may be considered 53, 54. Pneumatic balloon dilation is also an option when symptoms recur after botulinum toxin injection 55. In cases showing persistent or recurrent symptoms after Heller myotomy, retreatment with pneumatic balloon dilation may be considered 56. Heller myotomy is an effective treatment for the majority of achalasia patients. However, a small proportion of patients suffer persistent or recurrent symptoms after surgery. In such cases, the success rate of pneumatic balloon dilation after surgery was reported to vary from 50% to 78% 57. If the symptoms persist after POEM, pneumatic balloon dilation may be considered as salvage therapy depending on the clinical symptoms of the patient, although there are relatively few studies supporting this 58.

Oesophagectomy for end-stage achalasia

Despite the efficacy of pneumodilatation and laparoscopic Heller myotomy, 2–5% of patients will develop end-stage disease 59, defined as a massive dilatation of the esophagus with retention of food, unresponsive reflux disease, or the presence of preneoplastic lesions 60. In these cases, esophageal resection might be necessary to improve the patient’s quality of life and avoid the risk of invasive carcinoma. The risk of needing esophagectomy is higher if the esophagus is already markedly dilated at the first intervention than if it is mildly dilated (<4 cm) 61. Indeed, the presence of a megaesophagus (maximum esophageal diameter > 6 cm), could be a predictive factor for the need of esophagectomy 62.

In a recent systemic review, the postoperative morbidity ranged from 19% to 50% and the mortality ranged from 0.0% to 5.4% 62. Given the high morbidity and mortality, esophagectomy should be performed in patients with a megaesophagus who are fit for major surgery, complain of long-lasting disabling symptoms not responding to multiple endoscopic and surgical interventions, preferably in specialized centers.

The ideal reconstruction method after esophagectomy has not yet been established. Gastric interposition has the advantage of needing only one anastomosis, but gastro-esophageal reflux can cause severe damage if the anastomosis is intrathoracic. If a total esophagectomy is done and the anastomosis is in the neck, the critical vascular supply to the gastric tube can be compromised, resulting in anastomotic leakage and stricture 61. Alternatively, a long colonic interposition can be constructed, but anastomotic failure or stricture due to ischemia might occur. Short-segment colon interposition with an intrathoracic anastomosis might be a valid option in such patients. In a recent review that included 295 patients, an optimum outcome (defined as unrestricted or regular diet) was present in 65–100% of patients at a medium follow-up of 44 months (range 25–72), irrespective of the technique used.

Achalasia diet

The management of a person with achalasia and nutritional problems is very similar to that of patients with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) due to neurologic disease or esophagogastric cancer 63. Oral feeding has relevant psychosocial significance to patients and their families, and should be continued whenever possible. In some patients, oral intake is often not adequate even in the absence of significant swallowing difficulties. In mild to moderate achalasia, nutrition is generally mildly affected and if the family encourages the patient to follow dietary modifications, loss of weight and malnutrition rarely occurs.

Dysphagia diets should be highly individualized, including modification of food texture or fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or puréed, and fluids may be thickened 64.

If a person is unable to eat or drink or to consume sufficient quantities of food, or the risk of pulmonary aspiration is high, tube feeding should be provided. If there is a possibility for surgical myotomy, enteral nutrition via a nasal feeding tube will be adequate as a provisional measure, considering that a malnourished patient is always at major risk for postoperative complications. In very rare and selected cases of end-stage achalasia, in which there is any further possibility of surgery or pneumatic dilation, the insertion of the feeding tube through a percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy rather than a surgical gastrostomy would be the treatment of choice. Percutaneous gastric tube feeding is effective and usually acceptable to patients and their carers. Long-term complications include tube obstruction and wound infection. In some patients who are fed via a gastric tube, pulmonary aspiration may occur and routine intrajejunal feeding has been suggested for these cases 65.

References- O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2013;19(35):5806-5812. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5806. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3793135/

- Boeckxstaens GE. Achalasia: virus-induced euthanasia of neurons. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1610–1612. https://www.nature.com/articles/ajg2008334

- Gockel I, Müller M, Schumacher J. Achalasia–a disease of unknown cause that is often diagnosed too late. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:209–214. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3329145

- Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404–1414. https://www.nature.com/articles/ajg2005241

- Francis DL, Katzka DA. Achalasia: update on the disease and its treatment. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:369–374. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20600038

- Sandler RS, Nyrén O, Ekbom A, Eisen GM, Yuen J, Josefsson S. The risk of esophageal cancer in patients with achalasia: a population-based study. JAMA. 1995;274:1359–1362. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530170039029. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7563560

- Leeuwenburgh I, Scholten P, Alderliesten J, et al. Long-term esophageal cancer risk in patients with primary achalasia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2144–2149. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.263. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20588263

- Pandolfino, JE, Kwiatek, MA, Nealis, T et al. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008; 135: 1526–1533 http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(08)01332-2/fulltext

- AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ, American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2005 Jan; 128(1):209-24. http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(04)02004-9/fulltext

- Hong SJ, Bhargava V, Jiang Y, DeBoer D, Mittal RK. A unique esophagealmotor pattern that involves longitudinal is responsible for emptying in achalasia esophagus. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 102–11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2950263

- Kahrilas, P. J., Bredenoord, A. J., Fox, M., Gyawali, C. P., Roman, S., Smout, A. J., Pandolfino, J. E., & International High Resolution Manometry Working Group (2015). The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society, 27(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12477

- Patel, D. A., Lappas, B. M., & Vaezi, M. F. (2017). An Overview of Achalasia and Its Subtypes. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 13(7), 411–421. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5572971

- Boeckxstaens, G and Zaninotto, G. Achalasia and esophago-gastric junction outflow obstruction: focus on the subtypes. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012; 24: 27–31 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01833.x/full

- Ghoshal UC, Daschakraborty SB, Singh R. Pathogenesis of achalasia cardia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3050–3057. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3386318/

- Booy JD, Takata J, Tomlinson G, Urbach DR. The prevalence of autoimmune disease in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:209–213. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21899655

- Kraichely RE, Farrugia G, Pittock SJ, Castell DO, Lennon VA. Neural autoantibody profile of primary achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:307–311. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2819289/

- Aetiology of achalasia. http://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/872

- Castagliuolo I, Brun P, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Palù G, Costantino M, Baldan N, Zaninotto G. Esophageal achalasia: is the herpes simplex virus really innocent. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:24–30; discussion 30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14746832

- Lau KW, McCaughey C, Coyle PV, Murray LJ, Johnston BT. Enhanced reactivity of peripheral blood immune cells to HSV-1 in primary achalasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:806–813. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20438398

- Birgisson S, Galinski MS, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Richter JE. Achalasia is not associated with measles or known herpes and human papilloma viruses. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:300–306. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9052510

- Kaar TK, Waldron R, Ashraf MS, Watson JB, O’Neill M, Kirwan WO. Familial infantile oesophageal achalasia. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:1353–1354. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1793307/pdf/archdisch00644-0093.pdf

- Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404–1414. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15929777

- Gockel I, Müller M, Schumacher J. Achalasia–a disease of unknown cause that is often diagnosed too late. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:209–214. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3329145/

- Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. A study of swallowing difficulties in first degree relatives of patients with achalasia. Thorax. 1985;40:391–393. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC460073/pdf/thorax00233-0071.pdf

- Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Wu KL, Wu DC, Tai WC, Changchien CS. 2011 update on esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1573–1578. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3325522

- Kessing BF, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ. Erroneous diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Dec;9(12):1020-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.022

- Achalasia. Boeckxstaens, Guy E et al. The Lancet 4 January 2014, Volume 383 , Issue 9911 , 83 – 93

- Rohof, WO, Salvador, R, Annese, V et al. Outcomes of treatment for achalasia depend on manometric subtype. Gastroenterology. 2013; 144: 718–725 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23277105

- Eckardt, VF, Stauf, B, and Bernhard, G. Chest pain in achalasia: patient characteristics and clinical course. Gastroenterology. 1999; 116: 1300–1304 http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(99)70493-2/fulltext

- Eckardt, VF. Clinical presentations and complications of achalasia. (vi.)Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001; 11: 281–292 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11319062

- Vantrappen, G, Hellemans, J, Deloof, W et al. Treatment of achalasia with pneumatic dilatations. Gut. 1971; 12: 268–275 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1411631/pdf/gut00653-0044.pdf

- Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Aug;108(8):1238-49; quiz 1250. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.196

- Jung, H. K., Hong, S. J., Lee, O. Y., Pandolfino, J., Park, H., Miwa, H., Ghoshal, U. C., Mahadeva, S., Oshima, T., Chen, M., Chua, A., Cho, Y. K., Lee, T. H., Min, Y. W., Park, C. H., Kwon, J. G., Park, M. I., Jung, K., Park, J. K., Jung, K. W., … Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (2020). 2019 Seoul Consensus on Esophageal Achalasia Guidelines. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility, 26(2), 180–203. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20014

- Moonen A, Boeckxstaens G. Current diagnosis and management of achalasia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;48(6):484-90. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000137

- Tan Y, Zhu H, Li C, Chu Y, Huo J, Liu D. Comparison of peroral endoscopic myotomy and endoscopic balloon dilation for primary treatment of pediatric achalasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2016 Oct;51(10):1613-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.06.008

- van Hoeij, F. B., Prins, L. I., Smout, A., & Bredenoord, A. J. (2019). Efficacy and safety of pneumatic dilation in achalasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society, 31(7), e13548. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13548

- Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Rohof WO, Smout AJ, Tack J, Zwinderman AH, Zaninotto G, Busch OR; European Achalasia Trial Investigators. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011 May 12;364(19):1807-16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010502

- Hulselmans M, Vanuytsel T, Degreef T, Sifrim D, Coosemans W, Lerut T, Tack J. Long-term outcome of pneumatic dilation in the treatment of achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Jan;8(1):30-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.09.020

- Zhu Q, Liu J, Yang C. Clinical study on combined therapy of botulinum toxin injection and small balloon dilation in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dig Surg. 2009 Feb;26(6):493-8. doi: 10.1159/000229784

- Martínek J, Siroký M, Plottová Z, Bures J, Hep A, Spicák J. Treatment of patients with achalasia with botulinum toxin: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16(3):204-9. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2003.00329.x

- Vela MF, Richter JE, Wachsberger D, Connor J, Rice TW. Complexities of managing achalasia at a tertiary referral center: use of pneumatic dilatation, Heller myotomy, and botulinum toxin injection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Jun;99(6):1029-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30199.x

- Chao CY, Raj A, Saad N, Hourigan L, Holtmann G. Esophageal perforation, inflammatory mediastinitis and pseudoaneurysm of the thoracic aorta as potential complications of botulinum toxin injection for achalasia. Dig Endosc. 2015 Jul;27(5):618-21. doi: 10.1111/den.12392

- van Hoeij FB, Tack JF, Pandolfino JE, Sternbach JM, Roman S, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Complications of botulinum toxin injections for treatment of esophageal motility disorders†. Dis Esophagus. 2017 Feb 1;30(3):1-5. doi: 10.1111/dote.12491

- Zaninotto, G., Annese, V., Costantini, M., Del Genio, A., Costantino, M., Epifani, M., Gatto, G., D’onofrio, V., Benini, L., Contini, S., Molena, D., Battaglia, G., Tardio, B., Andriulli, A., & Ancona, E. (2004). Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia. Annals of surgery, 239(3), 364–370. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000114217.52941.c5

- Crespin OM, Liu LWC, Parmar A, Jackson TD, Hamid J, Shlomovitz E, Okrainec A. Safety and efficacy of POEM for treatment of achalasia: a systematic review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2017 May;31(5):2187-2201. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5217-y

- Park CH, Jung DH, Kim DH, Lim CH, Moon HS, Park JH, Jung HK, Hong SJ, Choi SC, Lee OY; Achalasia Research Group of the Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Comparative efficacy of per-oral endoscopic myotomy and Heller myotomy in patients with achalasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Oct;90(4):546-558.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.046

- Zaninotto G, Bennett C, Boeckxstaens G, Costantini M, Ferguson MK, Pandolfino JE, Patti MG, Ribeiro U Jr, Richter J, Swanstrom L, Tack J, Triadafilopoulos G, Markar SR, Salvador R, Faccio L, Andreollo NA, Cecconello I, Costamagna G, da Rocha JRM, Hungness ES, Fisichella PM, Fuchs KH, Gockel I, Gurski R, Gyawali CP, Herbella FAM, Holloway RH, Hongo M, Jobe BA, Kahrilas PJ, Katzka DA, Dua KS, Liu D, Moonen A, Nasi A, Pasricha PJ, Penagini R, Perretta S, Sallum RAA, Sarnelli G, Savarino E, Schlottmann F, Sifrim D, Soper N, Tatum RP, Vaezi MF, van Herwaarden-Lindeboom M, Vanuytsel T, Vela MF, Watson DI, Zerbib F, Gittens S, Pontillo C, Vermigli S, Inama D, Low DE. The 2018 ISDE achalasia guidelines. Dis Esophagus. 2018 Sep 1;31(9). doi: 10.1093/dote/doy071

- Li QL, Wu QN, Zhang XC, Xu MD, Zhang W, Chen SY, Zhong YS, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Qin WZ, Hu JW, Cai MY, Yao LQ, Zhou PH. Outcomes of per-oral endoscopic myotomy for treatment of esophageal achalasia with a median follow-up of 49 months. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Jun;87(6):1405-1412.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.10.031

- de Pascale S, Repici A, Puccetti F, Carlani E, Rosati R, Fumagalli U. Peroral endoscopic myotomy versus surgical myotomy for primary achalasia: single-center, retrospective analysis of 74 patients. Dis Esophagus. 2017 Aug 1;30(8):1-7. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox028

- Repici A, Fuccio L, Maselli R, Mazza F, Correale L, Mandolesi D, Bellisario C, Sethi A, Khashab MA, Rösch T, Hassan C. GERD after per-oral endoscopic myotomy as compared with Heller’s myotomy with fundoplication: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Apr;87(4):934-943.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.10.022

- Schlottmann F, Luckett DJ, Fine J, Shaheen NJ, Patti MG. Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy Versus Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) for Achalasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar;267(3):451-460. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002311

- Schneider AM, Louie BE, Warren HF, Farivar AS, Schembre DB, Aye RW. A Matched Comparison of Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy to Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy in the Treatment of Achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Nov;20(11):1789-1796. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3232-x

- Jung, H. E., Lee, J. S., Lee, T. H., Kim, J. N., Hong, S. J., Kim, J. O., Kim, H. G., Jeon, S. R., & Cho, J. Y. (2014). Long-term outcomes of balloon dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in patients with primary achalasia. The Korean journal of internal medicine, 29(6), 738–745. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2014.29.6.738

- Stewart RD, Hawel J, French D, Bethune D, Ellsmere J. S093: pneumatic balloon dilation for palliation of recurrent symptoms of achalasia after esophagomyotomy. Surg Endosc. 2018 Sep;32(9):4017-4021. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6271-4

- Saleh CM, Ponds FA, Schijven MP, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Efficacy of pneumodilation in achalasia after failed Heller myotomy. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Nov;28(11):1741-1746. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12875

- Xu MM, Kahaleh M. Recurrent symptoms after per-oral endoscopic myotomy in achalasia: Redo, dilate, or operate? A call for a tailored approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Jan;87(1):102-103. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.06.004

- van Hoeij FB, Ponds FA, Werner Y, Sternbach JM, Fockens P, Bastiaansen BA, Smout AJPM, Pandolfino JE, Rösch T, Bredenoord AJ. Management of recurrent symptoms after per-oral endoscopic myotomy in achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Jan;87(1):95-101. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.036

- Nabi Z, Reddy DN, Ramchandani M. Retreatment after failure of per-oral endoscopic myotomy: Does “cutting” fare better than “stretching”? Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Nov;86(5):927-928. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.05.031

- Duranceau, A, Liberman, M, Martin, J et al. End-stage achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012; 25: 319–330 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21166740

- Triadafilopoulos, G, Boeckxstaens, GE, Gullo, R et al. The Kagoshima consensus on esophageal achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012; 25: 337–348 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21595779

- Eldaif, SM, Mutrie, CJ, Rutledge, WC et al. The risk of esophageal resection after esophagomyotomy for achalasia. (discussion 62–63.)Ann Thorac Surg. 2009; 87: 1558–1562 http://www.annalsthoracicsurgery.org/article/S0003-4975(09)00359-2/fulltext

- Aiolfi A, Asti E, Bonitta G, Bonavina L. Esophagectomy for End-Stage Achalasia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2018 May;42(5):1469-1476. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4298-7

- Bower MR, Martin RC., 2nd Nutritional management during neoadjuvant therapy for esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:82–87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19373870

- Given MF, Hanson JJ, Lee MJ. Interventional radiology techniques for provision of enteral feeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:692–703. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16184329

- Zhao JG, Li YD, Cheng YS, et al. Long-term safety and outcome of a temporary self-expanding metallic stent for achalasia: A prospective study with a 13-year single-center experience. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1973–1980. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2705705/