Achlorhydria

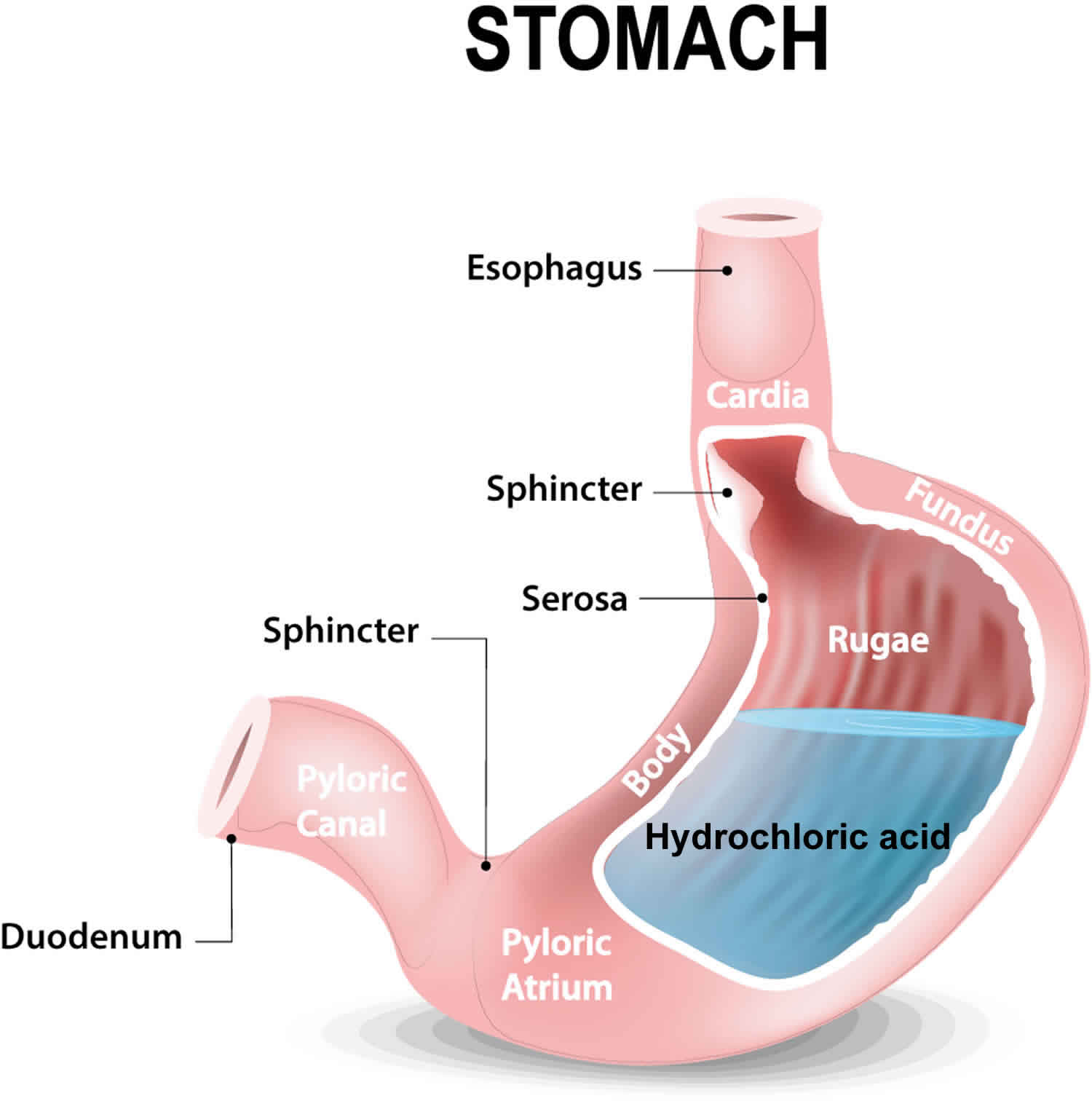

Achlorhydria also called hypochlorhydria, refers to uncommon conditions in which production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach is respectively absent or reduced. Achlorhydria is usually secondary to an underlying medical condition 1. Gastric acid is the fluid secreted by the stomach. It is composed of hydrochloric acid, potassium chloride, and sodium chloride. Hydrochloric acid plays an integral part in the digestion of food and protects our body against pathogens ingested with food or water. The parietal cells lining the stomach are mainly involved in its production 2.

Achlorhydria has many definitions. First, achlorhydria has been defined by a peak acid output in response to a maximally effective stimulus that results in an intragastric pH greater than 5.09 in men and greater than 6.81 in women 3. Second, achlorhydria has been defined by a maximal acid output of less than 6.9 m/mole/h in men and less than 5.0 m/mole/h in women. Third, achlorhydria has been defined as a ratio of serum pepsinogen I/pepsinogen II of less than 2.9.

In patients younger than 60 years of age, the incidence of achlorhydria and hypochlorhydria were 2.3% and 2% respectively; whereas, in older patients, it increased to 5% 2. That is an increase of almost 3-fold. Another study on autoimmune causes showed an age-related incidence of parietal cell autoantibodies. Their prevalence increases with age, for example, from 2.5% in the third decade to 12% in the eighth decade. Autoimmune gastritis is frequently found in association with other autoimmune conditions. It is also a component of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3. No association has been found between pernicious anemia and HLA types 4.

Achlorhydria causes

Multiple disorders can cause achlorhydria 5:

- Pernicious anemia (anemia that occurs when the small intestines cannot properly absorb vitamin B12 due to anti-parietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies): Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune phenomenon in which antibodies are formed. These autoantibodies cause the autoimmune destruction of parietal cells leading to atrophic gastritis.

- Use of antisecretory medications: Short-term standard dose treatment with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) has been shown to have low risk, but long-term use of proton pump inhibitor has been linked to hypochlorhydria.

- Helicobacter pylori infection: Acute Helicobacter pylori infection of gastric epithelial cells represses H-K-ATPase alpha subunit gene expression leading to transient hypochlorhydria and supporting Helicobacter pylori proliferation. This growth of Helicobacter pylori may even initiate a pathological process causing gastric cancer.

- Gastric bypass: Gastric bypass is a gastric exclusion operation performed in patients with massive obesity to reduce food intake. Studies show that the acid secretion unbuffered by the food in the excluded stomach results in lowered gastrin secretion hence leading to achlorhydria in such patients.

- VIPomas: VIPoma is an endocrine tumor that usually arises from beta-pancreatic cells and secretes Vasoactive intestinal peptide. It may be associated with MEN1. The massive amounts of VIP secretion cause watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, achlorhydria, vasodilation, hypercalcemia, and hyperglycemia.

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid): Thyroid hormone plays a role in hydrochloric acid secretion hence hypothyroidism can lead to achlorhydria.

- Radiation to stomach: Radiation to stomach has also been reported to cause achlorhydria.

- Gastric cancer: Animal studies have shown evidence of achlorhydria in gastric cancer.

Achlorhydria pathophysiology

Parietal cells lining the stomach wall are vital in maintaining the acidic pH of the stomach. They do this with the help of hydrogen potassium ATPase pump (HKA pump) which pushes potassium out and hydrogen back into the stomach. To keep the pump working, potassium ions must enter back into the stomach through the apical membrane. The apical membrane is lined with potassium-selective channels that are responsible for potassium ion efflux. These are called inward rectifier channels (Kir). A study conducted on knock out mice showed genetic evidence of one such channel: KCNE2-KCNQ1. KCNQ1 a transmembrane voltage-gated, homotetrameric potassium-selective channel. KCNE2 alters the voltage dependence of KCNQ1, converting it to a voltage-independent gate that has increased current conduction at low pH. KCNE2 and KCNQ1 are often found at the apical membrane of parietal cells. Targetted gene deletion of either of these subunits was found to result in achlorhydria. This study showed that these play an essential role in gastric acid secretion by maintaining the supply of luminal potassium to keep the HK-ATPase pump functional. In the same study, dysfunction of KCNQ1 also caused the development of gastric neoplasia independent of Helicobacter pylori infection (secondary to achlorhydria).

Thus any insult to parietal cells by any means (antibodies, surgery, drugs) can lead to achlorhydria which further activates multiple cascades of events that can lead to bacterial proliferation, gastrointestinal symptoms, and even gastric cancer.

Achlorhydria symptoms

Depending on the primary cause, the symptoms of achlorhydria can vary. Generally, patients develop following symptoms which are listed in order of their prevalence:

- Epigastric pain

- Weight loss

- Heartburn

- Nausea

- Bloating

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Acid regurgitation

- Early satiety

- Vomiting

- Postprandial fullness

- Constipation

- Dysphagia

- Glossitis

- Decreased position and vibration sense.

Achlorhydria complications

Majority of the complications found in achlorhydria are due to nutrient deficiency. They are also more common as compared to the other complications.

- Iron deficiency

- Vitamin-B12 deficiency

- Vitamin-D and calcium deficiency leading to osteoporosis and bone fracture

- Gastric adenocarcinoma

- Gastric carcinoid tumor

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome

Achlorhydria diagnosis

When suspecting achlorhydria, multiple tests are conducted to confirm the diagnosis and to find its primary cause:

- Antiparietal and anti-intrinsic factor antibody

- Biopsy of stomach

- Gastric pH monitoring

- Serum pepsinogen level (a low serum pepsinogen level indicates achlorhydria)

- Serum gastrin levels (high serum gastrin levels greater than 500 to 1000 pg/mL may indicate achlorhydria)

- Tests for detecting H. pylori infection (urea breath test, stool antigen test, biopsy, polymerase chain reaction-PCR or fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH])

- Hemoglobin level

Although not all patients with suspected achlorhydria need documentary evidence of a lack of acid production, the most important study to prove the presence of the condition is measurement of basal acid secretion.

For practical purposes, gastric pH at endoscopy should be done in patients with suspected achlorhydria. Older testing methods using fluid aspiration through a nasogastric tube can be done. These procedures can cause significant patient discomfort and are less efficient in obtaining a diagnosis. It has been proposed that fasting gastric pH can be predicted noninvasively using an equation based on the serum pepsinogen 1 level and the presence/absence of Helicobacter pylori.

A complete profile of gastric acid secretion is best obtained during a 24-hour gastric pH study.

Achlorhydria may also be documented by measurements of extremely low serum levels of pepsinogen A (< 17 mcg/L).

High serum gastrin levels (>500-1000 pg/mL) may support a diagnosis of achlorhydria.

Litmus paper is readily available to examine the pH of gastric secretions and, in contrast to the pH electrode, is less expensive while providing equally reliable results.

Helicobacter pylori infection can be inferred from the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies directed against Helicobacter pylori. If endoscopy is performed, the most convenient biopsy-based test is the urease enzyme test, which is based on a change in color of an indicator dye due to urea degradation. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimens is the most sensitive test, provided that a special stain (eg, a modified Giemsa or silver stain) permitting optimal visualization of Helicobacter pylori is used. Culture of Helicobacter pylori is the most specific test but is difficult.

Antiparietal cell antibody testing should be ordered because a strong association exists between achlorhydria and so-called autoimmune conditions. If achlorhydria is confirmed, patients should have a hydrogen breath test to check for bacterial overgrowth. Iron indices, calcium, prothrombin time, vitamin B-12, vitamin D, and thiamine levels should be checked to exclude deficiencies. Complete blood count with indices and peripheral smears can be examined to exclude anemia. Elevation of serum folate is suggestive of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Indeed, bacterial folate can be absorbed into the circulation.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

To exclude gastric carcinoids at the time of diagnosis, an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy may be indicated. Extensive literature examines the utility of upper GI endoscopy to screen patients with diabetes mellitus and antiparietal cell antibodies for gastric carcinoid tumors. Because of the low incidence of gastric carcinoid tumors, there is no evidence that upper GI endoscopy in screening these patients is of clinical benefit.

Gastric acid output measurement

Gastric acid output measurement consists of a timed collection of acid production; results are reported in mEq/h.

The patient is placed in the left lateral decubitus position. A nasogastric tube is passed into the antrum of the stomach after an overnight fast. Fluoroscopy can be used to guide accurate tube placement.

The initial aspirated fluid is discarded. A specimen is collected for 1 hour (at 15-min intervals) to assess fasting basal acid output (reference range, 1-6 mEq/h). Acid secretion is then stimulated by the administration of intravenous pentagastrin (2 U/kg). Four subsequent specimens in 15-minute aliquots are collected to determine maximal acid output (reference range, < 40 mEq/h).

Acidity is measured either by titration with the chemical indicator methyl red or by the use of a pH electrode. Patients with achlorhydria do not respond with an increase of acid output after pentagastrin stimulation.

Intragastric pH measurements

Intragastric pH measurements during endoscopy may be a valuable screening method.

A pH electrode for titration of H+ is passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. If the pH is found to be 4.0 or higher (and if no further decrease in pH occurs over time), patients may undergo a pentagastrin stimulation test.

More than 50% of patients whose initial stomach pH is 4.0 or higher are hypochlorhydric or achlorhydric.

Achlorhydria treatment

There is no specific treatment for achlorhydria 2. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori is recommended in patients who are found to have it. Other treatments are targeted at improving the complications of achlorhydria 6. Achlorhydria may be associated with vitamin B-12 deficiency in the setting of pernicious anemia. Parenteral vitamin B-12 may be important in selected patients. These include replacement of calcium, vitamin D and iron. Achlorhydria is also associated with thiamine (vitamin B-1) deficiency in the setting of bacterial overgrowth. Bacterial overgrowth is commonly treated with the following antimicrobials: metronidazole, amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium, ciprofloxacin, or rifaximin. There are no specific guidelines for surveillance, although achlorhydria is a preneoplastic condition. Even though there are no current guidelines on screening or monitoring of these patients, the clinician should always be aware that many cases of gastric cancer have been reported in achlorhydria patients 7. The Kyoto consensus in 2015 stated that endoscopic surveillance and follow up should be done in patients who underwent eradication therapy for H. pylori and were found to have a preneoplastic condition.

Helicobacter pylori –associated achlorhydria

Achlorhydria associated with Helicobacter pylori infection may respond to Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, although resumption of gastric acid secretion may only be partial.

The standard, first-line therapy for gastric Helicobacter pylori is as follows: proton pump inhibitor use (20 mg oral twice daily) plus clarithromycin (500 mg oral twice daily) plus amoxicillin (1 g oral twice daily). For patients who are allergic to penicillin, amoxicillin can be replaced by levofloxacin (250 mg oral twice daily).

There is some minor disagreement on the duration of treatment. US guidelines recommend a 14-day course, while in Europe, a 7-day course is considered to be sufficient. A meta-analysis reveals a 12% advantage for a longer course of treatment, but this is at an added expense and a greater risk of adverse effects. Patient compliance is also more difficult with a longer course of treatment (ie, 14 days vs 7 days).

Immune-mediated diseases

In immune-mediated diseases (eg, pernicious anemia), acid secretion cannot be restored after destruction of the gastric secretory mucosa.

Treatment of gastritis that leads to pernicious anemia consists of parenteral vitamin B-12 injection. It is not clear whether intranasal vitamin B-12 therapy is adequate in individuals who have been diagnosed with pernicious anemia. Parenteral vitamin B-12 treatment may reverse the hematologic abnormalities. However, it may have little effect on preexisting neurologic abnormalities. This treatment does not affect the underlying gastric atrophy, inflammation, or the possible development of gastric carcinoma and should be followed with these risks in mind.

Associated immune-mediated conditions (eg, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroiditis) should also be treated. However, treatment of these disorders has no known beneficial effect on achlorhydria.

Bacterial overgrowth

The normal indigenous intestinal microflora consists of about 1015 bacteria that mainly reside in the lower gut. Bacterial overgrowth implies abnormal bacterial colonization of greater than 100,000/mL in the upper gut.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth can result in recurrent diarrhea with malabsorption, D-lactic acidosis, and an increased risk of endogenous infection. Other conditions associated with small bowel bacterial overgrowth include steatorrhea, macrocytic anemia, and, less commonly, protein-losing enteropathy.

Microecologic changes are accompanied by vitamin B-12 deficiency anemia, hypovitaminosis, protein deficiency, translocation of bacteria and their toxins from the intestine into the bloodstream, emergence of endotoxinemia, and possible generalization of infection. Bacterial overgrowth is diagnosed by the concentration of hydrogen in expiratory flow (glucose-hydrogen breath test) or by bacteriological study of aspirate from the proximal part of the small intestine.

Antimicrobial agents, including metronidazole, amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium, ciprofloxacin, and rifaximin, can be used to treat bacterial overgrowth.

Long-term proton pump inhibitor use

Achlorhydria resulting from long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use may be treated by dose reduction or withdrawal of the proton pump inhibitor.

Gastric reacidification

Achlorhydria from proton pump inhibitor use may also be corrected by administration of hydrochloric acid supplements. More recently, betaine hydrochloride (BHCl) has been used as a gastric acid supplement and is available over the counter as a nutraceutical. In healthy volunteers with pharmacologically induced hypochlorhydria, betaine hydrochloride has been shown to temporarily reduce the gastric pH, but cessation of proton pump inhibitor therapy is often enough to correct medication-induced achlorhydria 8.

Surgery for carcinoid tumors

Surgery is the only potentially curative therapy for carcinoid tumors 9.

Surgical antrectomy results in normalization of serum gastrin levels and disappearance of multicentric gastric carcinoids. In a study by Hirschowitz et al 10, antrectomy resulted in normalization of serum gastrin levels within 8 hours and disappearance of carcinoids in 6-16 weeks.

Gladdy et al 9 examined the efficacy of endoscopic surveillance versus surgical resection in the treatment of patients with type I gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors. In the study, 46 patients underwent endoscopic surveillance with polypectomy, while 19 patients were treated with gastric resection. The latter treatment was used in patients with larger-sized tumors, increased depth of invasion, and solitary tumors. The 5-year recurrence-free survival rate was 75% in the surgical resection patients, but the disease-specific survival rate was 100% in both patient groups. Concomitant adenocarcinoma was found in 4 of the patients who underwent resection, with the detection made through preoperative biopsy in 2 of these individuals. The carcinoid tumors were bigger and the carcinoid disease was more advanced in all patients with coexisting gastric adenocarcinoma.

The authors recommended that resection be considered for patients with more advanced carcinoid disease, owing to the increased adenocarcinoma risk associated with the advanced disorder. They also concluded that endoscopic surveillance is appropriate for determining the status of carcinoid tumors and for the assessment of the dysplasia or adenocarcinoma that can arise in association with type 1 gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors.

Achlorhydria prognosis

Several conditions associated with achlorhydria lead to increased mortality and morbidity. Specifically, achlorhydria has been associated with the following major sequelae: gastric cancer, hip fracture, and bacterial overgrowth.

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a chronic condition. Bacterial overgrowth is underrecognized. It is the most common cause of malabsorption among older adults. Competition between bacteria and the human host for ingested nutrients leads to malabsorption and considerable morbidity due to micronutrient deficiency.

Clinical symptoms, including chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, macrocytic anemia, weight loss, and protein-losing enteropathy, can be seen in these patients.

There are reports of cycling of antibiotics to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance. Retreatment may be necessary once every 1-6 months.

Carcinoid tumors

Achlorhydria is an important cause of hypergastrinemia, which can subsequently lead to the development of gastric carcinoid tumor and gastric adenocarcinoma.

In a report from the American Cancer Society, approximately 5000 carcinoid tumors are diagnosed each year in the United States. Statistics from the National Cancer Institute demonstrate that approximately 74% of these tumors originate in the gastrointestinal tract, whereas 8.7% of all enteric carcinoid tumors originate in the stomach.

Mortality specific to gastric carcinoid tumor has previously been studied and is as follows: 5-year survival is 64% with localized disease, 40% with regional disease, and 10% with distant disease spread.

Hip fracture

Long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, particularly at high doses, is associated with an increased risk of hip fracture. The mortality rate during the first year after a hip fracture is 20%. Among those who survive, 1 in 5 patients require nursing home care.

These findings suggest an association between achlorhydria related to proton pump inhibitor use and hip fracture. Several potential mechanisms may explain this association. Significant hypochlorhydria, particularly in the elderly, who may have a higher prevalence of& H pylori infection, could result in calcium malabsorption secondary to small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Limited animal and human studies have shown that proton pump inhibitor therapy may decrease insoluble calcium absorption or bone density. In addition, in vitro data suggests that proton pump inhibitor therapy may inhibit osteoclastic vacuolar H+/K+ -ATPase and result in decreased bone resorption.

References- Furuta T, Baba S, Yamade M, Uotani T, Kagami T, Suzuki T, Tani S, Hamaya Y, Iwaizumi M, Osawa S, Sugimoto K. High incidence of autoimmune gastritis in patients misdiagnosed with two or more failures of H. pylori eradication. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018 Aug;48(3):370-377

- Fatima R, Aziz M. Achlorhydria. [Updated 2019 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507793

- Achlorhydria. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/170066-overview

- Villanacci V, Casella G, Lanzarotto F, Di Bella C, Sidoni A, Cadei M, Salviato T, Dore MP, Bassotti G. Autoimmune gastritis: relationships with anemia and Helicobacter pylori status. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017 Jun – Jul;52(6-7):674-677.

- Chen C, Zheng Z, Li B, Zhou L, Pang J, Wu W, Zheng C, Zhao Y. Pancreatic VIPomas from China: Case reports and literature review. Pancreatology. 2019 Jan;19(1):44-49.

- Lechner K, Födinger M, Grisold W, Püspök A, Sillaber C. [Vitamin B12 deficiency. New data on an old theme]. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2005 Sep;117(17):579-91.

- Kayamba V, Shibemba A, Zyambo K, Heimburger DC, Morgan DR, Kelly P. High prevalence of gastric intestinal metaplasia detected by confocal laser endomicroscopy in Zambian adults. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184272

- Yago MR, Frymoyer AR, Smelick GS, et al. Gastric reacidification with betaine HCl in healthy volunteers with rabeprazole-induced hypochlorhydria. Mol Pharm. 2013 Nov 4. 10(11):4032-7.

- Gladdy RA, Strong VE, Coit D, et al. Defining surgical indications for type I gastric carcinoid tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009 Nov. 16(11):3154-60.

- Hirschowitz BI, Griffith J, Pellegrin D, Cummings OW. Rapid regression of enterochromaffinlike cell gastric carcinoids in pernicious anemia after antrectomy. Gastroenterology. 1992 Apr. 102(4 Pt 1):1409-18.