What is Addison’s disease

Addison’s disease also known as primary adrenal insufficiency or hypoadrenalism, is a rare endocrine disorder that occurs when your adrenal glands do not produce enough of their hormones – cortisol (a “stress” hormone) and aldosterone and androgens (the other hormones made by the adrenal glands) 1. Addison’s disease can be caused by damage to the adrenal glands, autoimmune conditions, and certain genetic conditions. Some of the symptoms include changes in blood pressure, chronic diarrhea, darkening of the skin, paleness, extreme weakness, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, salt craving, and weight loss. Treatment with replacement corticosteroids usually controls the symptoms. You’ll need to take the hormones to replace those that are missing for the rest of your life.

Addison’s disease, the common term for primary adrenal insufficiency, occurs when the adrenal glands are damaged and cannot produce enough of the adrenal hormone cortisol. The adrenal hormone aldosterone and androgens may also be lacking. Addison’s disease is seen in all age groups and affects male and female equally. Addison’s disease affects 110 to 144 of every 1 million people in developed countries 2. Because the estimated prevalence of Addison disease is one in 20,000 persons in the United States and Western Europe, a high clinical suspicion is needed to avoid misdiagnosing a life-threatening Addisonian crisis (also known as acute adrenal crisis, acute adrenal failure adrenal crisis or acute adrenal insufficiency) 3. Addison’s disease symptoms are gradual and worsen over a period of years, making early diagnosis difficult 4. Addison disease is usually diagnosed after a significant stress or illness unmasks cortisol and mineralocorticoid deficiency, presenting as shock, hypotension (low blood pressure) and volume depletion (adrenal crisis or Addisonian crisis) 5. Cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies contribute to hypotension, orthostasis, and shock; however, adrenal crisis is more likely to occur in primary adrenal insufficiency compared with secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Your adrenal glands are composed of two sections (see Figure 1). The interior (the adrenal medulla) produces adrenaline-like hormones. The outer layer (the adrenal cortex) produces a group of hormones called corticosteroids, which include glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids and male sex hormones (androgens).

Some of the hormones the adrenal glands cortex produces are essential for life — the glucocorticoids (Cortisol) and the mineralocorticoids (Aldosterone). Addison’s disease treatment involves taking hormones to replace those that are missing.

The cause of Addison’s disease has dramatically changed from an infectious cause to autoimmune pathology since its initial description. Addison’s disease is usually the result of a problem with the immune system, which causes it to attack the outer layer of the adrenal gland (the adrenal cortex), disrupting the production of the steroid hormones aldosterone and cortisol. However, tuberculosis (TB) is still the predominant cause of Addison’s disease in developing countries 6.

Addison’s disease is named after Thomas Addison, who first described patients affected by this disorder in 1855, in the book titled “On the constitutional and local effects of the disease of supra renal capsule” 7. Addison’s disease can present as a life-threatening crisis also known as Addisonian crisis or adrenal crisis, because it is frequently unrecognized in its early stages. Addison’s disease signs and symptoms can be subtle and nonspecific 8. Early-stage symptoms of Addison’s disease are similar to other more common health conditions, such as depression or flu.

Early symptoms of Addison’s disease may include 9:

- lack of energy or motivation (fatigue)

- muscle weakness

- low mood

- loss of appetite and unintentional weight loss

- increased thirst

Over time, these problems may become more severe and you may experience further symptoms, such as dizziness, fainting, cramps and exhaustion.

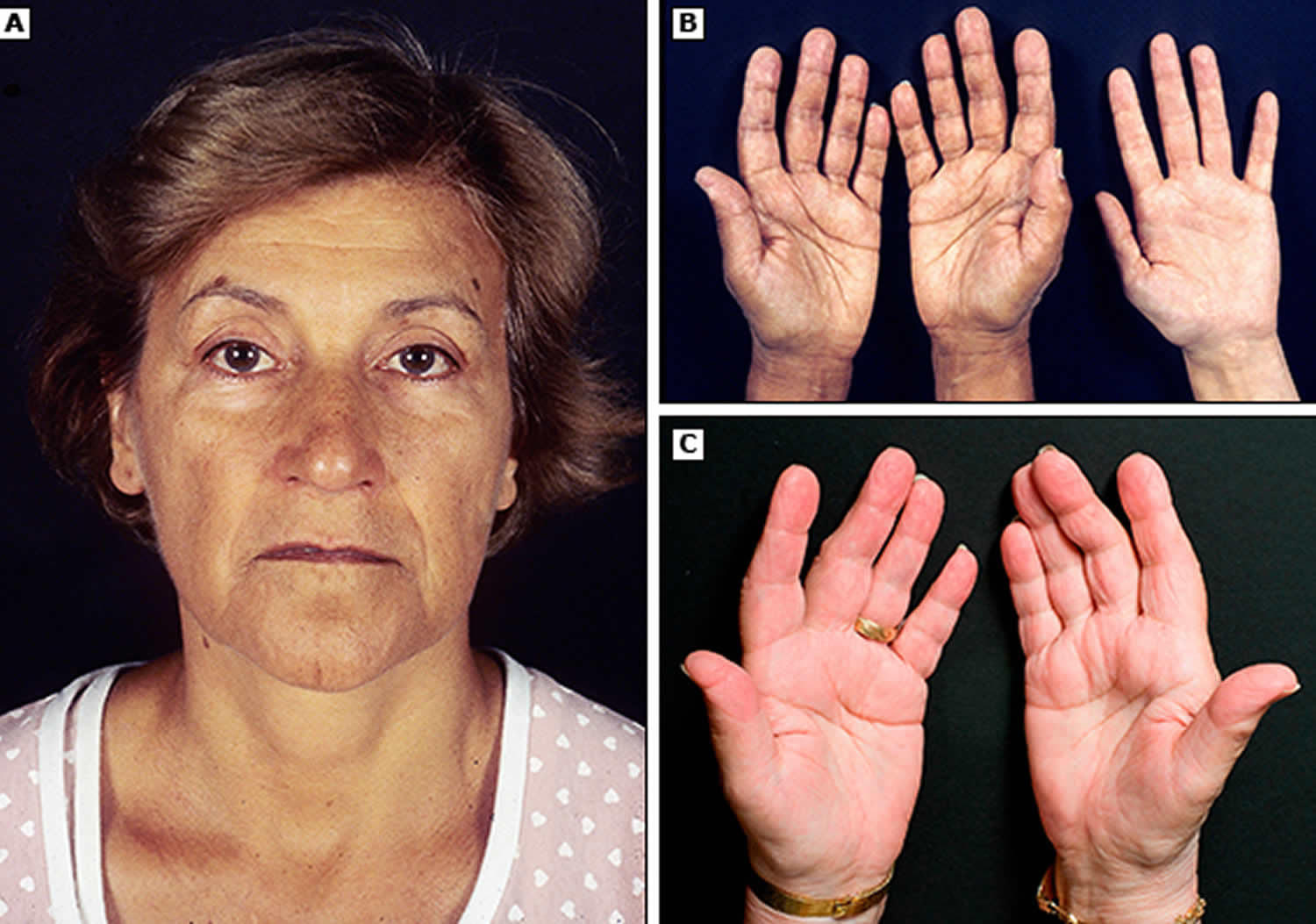

You may also develop small areas of darkened skin, or darkened lips or gums (hyperpigmentation). Hyperpigmentation is the physical finding most characteristic of Addison disease, arising from continual stimulation of the corticotrophs in the anterior pituitary. Specifically, hyperpigmentation results from cross-reactivity between the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) produced by the corticotrophs and the melanocortin 1 receptor on keratinocytes. Hyperpigmentation is usually generalized over the entire body and can be found in palmar creases, buccal mucosa, vermilion border of the lips, and around scars and nipples. It is not a feature of secondary adrenal insufficiency because of the lack of increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in these patients.

These symptoms relate to the degree of cortisol, mineralocorticoid, and adrenal androgen deficiency 8.

Although these symptoms are not always caused by Addison’s disease, you should see a doctor so they can be investigated.

Addison’s disease treatment usually involves corticosteroid (steroid) replacement therapy for life. Corticosteroid medicine is used to replace the hormones cortisol and aldosterone that your body no longer produces. A medicine called hydrocortisone is usually used to replace the cortisol. Other possible medicines are prednisolone or dexamethasone, although these are less commonly used.

Aldosterone is replaced with a medicine called fludrocortisone. Your doctor may also ask you to add extra salt to your daily diet, although if you’re taking enough fludrocortisone medicine this may not be necessary. Unlike most people, if you feel the urge to eat something salty, then you should eat it.

In general, the medicines used for Addison’s disease do not have side effects, unless your dose is too high. If you take a higher dose than necessary for a long time, there’s a risk of problems such as weakened bones (osteoporosis), mood swings and difficulty sleeping (insomnia).

See your doctor if you have common signs and symptoms of Addison’s disease, such as:

- Darkening areas of skin (hyperpigmentation)

- Severe fatigue

- Unintentional weight loss

- Gastrointestinal problems, such as nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain

- Lightheadedness or fainting

- Salt cravings

- Muscle or joint pains

Figure 1. Adrenal gland anatomy

What do adrenal hormones do ?

Adrenal hormones, such as cortisol and aldosterone, play key roles in the functioning of the human body, such as regulating blood pressure; metabolism, the way the body uses digested food for energy; and the body’s response to stress. In addition, the body uses the adrenal hormone dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to make androgens and estrogens, the male and female sex hormones.

Cortisol

Cortisol belongs to the class of hormones called glucocorticoids, which affect almost every organ and tissue in the body. Cortisol’s most important job is to help the body respond to stress. Among its many tasks, cortisol helps:

- maintain blood pressure and heart and blood vessel function

- slow the immune system’s inflammatory response—how the body recognizes and defends itself against bacteria, viruses, and substances that appear foreign and harmful

- regulate metabolism

The amount of cortisol produced by the adrenal glands is precisely balanced. Like many other hormones, cortisol is regulated by the hypothalamus, which is a part of the brain, and the pituitary gland. First, the hypothalamus releases a “trigger” hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary gland to send out adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. Cortisol then signals back to both the pituitary gland and hypothalamus to decrease these trigger hormones.

Figure 2. ACTH and Cortisol production and control by the hypothalamus (the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis)

[Source 10]

[Source 10]Figure 3. Negative feedback regulates cortisol secretion

Aldosterone

Aldosterone belongs to the class of hormones called mineralocorticoids, also produced by the adrenal glands. Aldosterone helps maintain blood pressure and the balance of sodium and potassium in the blood. When aldosterone production falls too low, the body loses too much sodium and retains too much potassium.

The decrease of sodium in the blood can lead to a drop in both blood volume—the amount of fluid in the blood—and blood pressure. Too little sodium in the body also can cause a condition called hyponatremia. Symptoms of hyponatremia include feeling confused and fatigued and having muscle twitches and seizures.

Too much potassium in the body can lead to a condition called hyperkalemia. Hyperkalemia may have no symptoms; however, it can cause irregular heartbeat, nausea, and a slow, weak, or an irregular pulse.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is another hormone produced by your adrenal glands. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a precursor hormone, which means it has little biological effect on its own, but has powerful effects when converted into sex hormones such as testosterone and estradiol. The body uses dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to make the sex hormones, androgen and estrogen. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is produced from cholesterol mainly by the outer layer of the adrenal glands (the adrenal cortex), although it is also made by the testes and ovaries in small amounts. With adrenal insufficiency, the adrenal glands may not make enough dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Healthy men derive most androgens from the testes. Healthy women and adolescent girls get most of their estrogens from the ovaries. In women, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is an important source of estrogens in the body – it provides about 75% of estrogens before the menopause, and 100% of estrogens in the body after menopause. However, women and adolescent girls may have various symptoms from DHEA insufficiency, such as loss of pubic hair, dry skin, a reduced interest in sex, and depression.

Addison’s disease pathophysiology

Adrenal gland failure in Addison’s disease results in decreased cortisol production initially followed by that of aldosterone, both of which will eventually result in an elevation of adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) hormones due to the loss of negative feedback inhibition 11. Melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) is produced from the same precursor molecule as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) called pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC).

Hyperpigmentation or abnormal darkening of the skin is found in patients with primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease). In Addison’s disease, the adrenal glands do not produce enough hormones (including cortisol). As a consequence, the hypothalamus stimulates the pituitary gland to release more adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to try and stimulate the adrenal glands to produce more cortisol. Adrenocorticotropic hormone can be broken down to produce melanocyte-stimulating hormone, leading to hyperpigmentation of the skin.

Addison’s disease causes

Addison’s disease results when your adrenal glands are damaged, producing insufficient amounts of the hormone cortisol and often aldosterone as well. The adrenal glands are located just above your kidneys. Your adrenal glands are composed of two sections. The interior (the adrenal medulla) produces adrenaline-like hormones. The outer layer (the adrenal cortex) produces a group of hormones called corticosteroids. Corticosteroids include:

- Glucocorticoids. These hormones, which include cortisol, influence your body’s ability to convert food into energy, play a role in your immune system’s inflammatory response and help your body respond to stress.

- Mineralocorticoids. These hormones, which include aldosterone, maintain your body’s balance of sodium and potassium to keep your blood pressure normal.

- Androgens. These male sex hormones are produced in small amounts by the adrenal glands in both men and women. They cause sexual development in men, and influence muscle mass, sex drive (libido) and a sense of well-being in both men and women.

The failure of your adrenal glands to produce adrenocortical hormones is most commonly the result of the body attacking itself (autoimmune disease). An auto-immune disorder in which the body’s immune system makes antibodies which attack the cells of the adrenal cortex and slowly destroys them. This can take months to years. For unknown reasons, your immune system views the adrenal cortex as foreign, something to attack and destroy.

Other causes of adrenal gland failure may include:

- Tuberculosis (TB). Tuberculosis was the leading cause of Addison disease up until the middle of the 20th century, when antibiotics were introduced that successfully treated tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (TB) is the most common cause of Addison’s disease worldwide, but it’s rare in the US. Tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection that mostly affects the lungs but can also spread to other parts of your body. It can cause Addison’s disease if it damages your adrenal glands.

- Infections (bacterial, fungal, tuberculosis) of the adrenal glands e.g. cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- Cancer that spreads to the adrenal glands

- Surgical removal of the adrenal glands

- Amyloidosis—protein build up in organs (very rare)

- Bleeding into the adrenal glands, which may present as adrenal crisis without any preceding symptoms.

Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: Addison’s Disease

The outer layer of the adrenal glands is called the adrenal cortex. If the cortex is damaged, it may not be able to produce enough cortisol.

A common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is an autoimmune disease that causes the immune system to attack healthy tissues. In the case of Addison’s disease, the immune system turns against the adrenal gland(s). There are some very rare syndromes (several diseases that occur together) that can cause autoimmune adrenal insufficiency.

Autoimmune Disorders

Up to 80 percent of Addison’s disease cases are caused by an autoimmune disorder, which is when the body’s immune system attacks the body’s own cells and organs 12. In autoimmune Addison’s disease, which mainly occurs in middle-aged females, the immune system gradually destroys the adrenal cortex—the outer layer of the adrenal glands 12.

Autoimmune Addison’s disease can be divided into stages of progression (Table 1) 13, 14. As autoimmune Addison’s disease develops, individuals lose adrenocortical function over a period of years. In the first three stages, the human leukocyte antigen genes confer genetic risk; an unknown precipitating event initiates antiadrenal autoimmunity; and 21-hydroxylase antibodies are produced, which predict future disease. The production of 21-hydroxylase antibodies can precede symptom onset by years to decades, and they are present in more than 90% of recent-onset cases 15. In the fourth stage, overt adrenal insufficiency develops. Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease) occurs when at least 90 percent of the adrenal cortex has been destroyed 2. As a result, both cortisol and aldosterone are often lacking. Sometimes only the adrenal glands are affected. Sometimes other endocrine glands are affected as well, as in polyendocrine deficiency syndrome.

One of the first metabolic abnormalities to occur is an increase in plasma renin level, followed by the sequential development of other abnormalities, including a decreased response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation in the fifth stage. If symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are present but go undiagnosed, an Addisonian crisis can occur.

Table 1. Development stages of Autoimmune Addison’s disease

| Stage | Symptoms | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Genetic risk | None | HLA-B8, -DR3, and -DR4 genes confer risk |

| 2. Precipitating event starts antiadrenal autoimmunity | None | Possible environmental trigger |

| 3. 21-hydroxylase antibodies present | None | Antibodies appear before disease onset in 90% of cases |

| 4. Metabolic decompensation | Fatigue, anorexia, nausea, hyperpigmentation | Increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and decreased 8 a.m. cortisol levels; high clinical suspicion needed for diagnosis |

| 5. Decreased response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation | Hypotension and shock (addisonian crisis) | Severe symptoms can be life-threatening |

Approximately 50% of persons with Addison’s disease caused by autoimmune adrenalitis develop another autoimmune disorder during their lifetime, necessitating lifelong vigilance for associated autoimmune conditions 16. Of note, 10% of women with Addison disease experience autoimmune premature ovarian failure or primary ovarian insufficiency, in their reproductive years with signs and symptoms of estrogen deficiency (e.g., amenorrhea, flushing, fatigue, poor concentration) 17. It is appropriate to offer these patients evaluation and counseling on other options for building a family 18.

Risk factors for the autoimmune type of Addison’s disease include other autoimmune diseases:

- Type 1 diabetes

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Hypopituitarism

- Pernicious anemia

- Graves’ disease

- Chronic thyroiditis

- Dermatis herpetiformis

- Vitiligo

- Myasthenia gravis

Table 2. Autoimmune diseases occurring with Addison’s disease

| Disease | Lifetime prevalence (%) | Appropriate diagnostic tests |

|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto disease or Graves disease) 16 | 22 | Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid peroxidase antibody, and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin levels |

| Celiac disease 19 | 12 | Tissue transglutaminase antibody level |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus 20 | 11 | HbA1C, fasting blood glucose, and islet autoantibody levels |

| Hypoparathyroidism 21 | 10 | Calcium and parathyroid hormone levels |

| Primary ovarian insufficiency 22 | 10 | Follicle-stimulating hormone level |

| Pernicious anemia 16 | 5 | Complete blood count, vitamin B12 level, and parietal cell antibody level |

| Primary gonadal failure (testes) 20 | 2 | Testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone levels |

| None 17 | 50 | — |

Footnote: Data compiled from multiple studies across different populations.

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome is a rare cause of Addison’s disease. Sometimes referred to as multiple endocrine deficiency syndrome, polyendocrine deficiency syndrome is classified into type 1 and type 2.

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 is inherited and occurs in children. Symptoms start during childhood. Almost any organ can be affected by autoimmune damage. Fortunately it is extremely rare—only several hundred cases have been reported worldwide. Conditions associated with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 include:

In addition to adrenal insufficiency, these children may have:

- Underactive parathyroid glands, which are four pea-sized glands located on or near the thyroid gland in the neck; they produce a hormone that helps maintain the correct balance of calcium in the body.

- Delayed or slow sexual development.

- Vitamin B12 malabsorption / deficiency (pernicious anemia), a severe type of anemia; anemia is a condition in which red blood cells are fewer than normal, which means less oxygen is carried to the body’s cells. With most types of anemia, red blood cells are smaller than normal; however, in pernicious anemia, the cells are bigger than normal.

- Candidiasis (chronic yeast infection).

- Chronic hepatitis, a liver disease.

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome Type 2

Researchers think autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 2, which is sometimes called Schmidt’s syndrome, is also inherited. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 2 usually affects young adults, symptoms primarily develop in adults aged 18 to 30 and may include:

- Addison’s disease

- Underactive or overactive thyroid function

- Delayed or slow sexual development

- Diabetes, in which a person has high blood glucose, also called high blood sugar or hyperglycemia

- White skin patches, a loss of pigment on areas of the skin (vitiligo)

- Celiac disease 23

Secondary adrenal insufficiency

Adrenal insufficiency can also occur if your pituitary gland is diseased. The pituitary gland makes a hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce its hormones. Inadequate production of ACTH can lead to insufficient production of hormones normally produced by your adrenal glands, even though your adrenal glands aren’t damaged. Secondary adrenal insufficiency can occur if your pituitary gland becomes damaged – for example, because of a tumor on the pituitary gland (pituitary adenoma). Doctors call this condition secondary adrenal insufficiency and is a separate condition to Addison’s disease.

Another more common cause of secondary adrenal insufficiency occurs when people who take corticosteroids for treatment of chronic conditions, such as asthma or arthritis, abruptly stop taking the corticosteroids.

Stoppage of Corticosteroid Medication

A temporary form of secondary adrenal insufficiency may occur when a person who has been taking a synthetic glucocorticoid hormone, called a corticosteroid, for a long time stops taking the medication. Corticosteroids are often prescribed to treat inflammatory illnesses such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and ulcerative colitis. In this case, the prescription doses often cause higher levels than those normally achieved by the glucocorticoid hormones created by the body. When a person takes corticosteroids for prolonged periods, the adrenal glands produce less of their natural hormones. Once the prescription doses of corticosteroid are stopped, the adrenal glands may be slow to restart their production of the body’s glucocorticoids. To give the adrenal glands time to regain function and prevent adrenal insufficiency, prescription corticosteroid doses should be reduced gradually over a period of weeks or even months. Even with gradual reduction, the adrenal glands might not begin to function normally for some time, so a person who has recently stopped taking prescription corticosteroids should be watched carefully for symptoms of secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Surgical Removal of Pituitary Tumors

Another cause of secondary adrenal insufficiency is surgical removal of the usually noncancerous, ACTH-producing tumors of the pituitary gland that cause Cushing’s syndrome. Cushing’s syndrome is a hormonal disorder caused by prolonged exposure of the body’s tissues to high levels of the hormone cortisol. When the tumors are removed, the source of extra ACTH is suddenly gone and a replacement hormone must be taken until the body’s adrenal glands are able to resume their normal production of cortisol. The adrenal glands might not begin to function normally for some time, so a person who has had an ACTH-producing tumor removed and is going off of his or her prescription corticosteroid replacement hormone should be watched carefully for symptoms of adrenal insufficiency.

Changes in the Pituitary Gland

Less commonly, secondary adrenal insufficiency occurs when the pituitary gland either decreases in size or stops producing ACTH. These events can result from

- tumors or an infection in the pituitary

- loss of blood flow to the pituitary

- radiation for the treatment of pituitary or nearby tumors

- surgical removal of parts of the hypothalamus

- surgical removal of the pituitary

Infections

Tuberculosis (TB), an infection that can destroy the adrenal glands, accounts for 10 to 15 percent of Addison’s disease cases in developed countries. When primary adrenal insufficiency was first identified by Dr. Thomas Addison in 1849, tuberculosis (TB) was the most common cause of the disease. As tuberculosis (TB) treatment improved, the incidence of Addison’s disease due to tuberculosis (TB) of the adrenal glands greatly decreased. However, recent reports show an increase in Addison’s disease from infections such as tuberculosis (TB) and cytomegalovirus. Cytomegalovirus is a common virus that does not cause symptoms in healthy people; however, it does affect babies in the womb and people who have a weakened immune system—mostly due to HIV/AIDS. Other bacterial infections, such as Neisseria meningitidis, which is a cause of meningitis, and fungal infections can also lead to Addison’s disease.

Other Causes

Less common causes of Addison’s disease are:

- Spread of cancer to the adrenal glands

- Amyloidosis, a serious, though rare, group of diseases that occurs when abnormal proteins, called amyloids, build up in the blood and are deposited in tissues and organs

- Surgical removal of both adrenal glands (adrenalectomy) – for example, to remove a tumor

- Bleeding into the adrenal glands, which may present as adrenal crisis without any preceding symptoms. Very heavy bleeding into the adrenal glands, sometimes associated with meningitis or other types of severe sepsis.

- Genetic defects including abnormal adrenal gland development, an inability of the adrenal glands to respond to ACTH, or a defect in adrenal hormone production

- Medication-related causes, such as from anti-fungal medications (e.g., ketoconazole) and the anesthetic etomidate, which may be used when a person undergoes a rapid sequence intubation for patients requiring mechanical ventilation. The effect of etomidate is dose-dependent 24.

- Intubation—the placement of a flexible, plastic tube through the mouth and into the trachea, or windpipe, to assist with breathing.

- Adrenoleukodystrophy – a rare, life-limiting inherited condition that affects the adrenal glands and nerve cells in the brain, and is mostly seen in young boys

- Certain treatments needed for Cushing’s syndrome – a collection of symptoms caused by very high levels of cortisol in the body

Addison’s disease symptoms

Addison’s disease symptoms usually develop slowly, often over several months. Often, Addison’s disease progresses so slowly that symptoms are ignored until a stress, such as illness or injury, occurs and makes symptoms worse.

Addison’s disease signs and symptoms may include:

- Extreme fatigue, chronic, or long lasting, fatigue

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite or decreased appetite

- Darkening of your skin (hyperpigmentation)

- Low blood pressure that drops further when a person stands up, causing dizziness or fainting

- Salt craving

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- Nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Muscle or joint pains

- Muscle weakness

- Irritability

- Depression

- Body hair loss or sexual dysfunction in women

- Headache

- Sweating

- Irregular or absent menstrual periods

- In women, loss of interest in sex.

Hyperpigmentation, or darkening of the skin, can occur in Addison’s disease. This darkening is most visible on scars; skin folds; pressure points such as the elbows, knees, knuckles, and toes; lips; and mucous membranes such as the lining of the cheek.

The slowly progressing symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are often ignored until a stressful event, such as surgery, a severe injury, an illness, or pregnancy, causes them to worsen.

Figure 3. Hyperpigmentation in the hand

Figure 4. Hyperpigmentation in the mouth

Figure 5. Hyperpigmentation in the mouth

Acute adrenal failure (Addisonian crisis or adrenal crisis)

Sudden, severe worsening of adrenal insufficiency symptoms is called adrenal crisis. If the person has Addison’s disease, this worsening can also be called an Addisonian crisis. Each year, typically 8% of people with Addison’s disease experience Addisonian crisis (adrenal crisis). This means they need extra steroid medication immediately, in the form of an emergency injection of intra-muscular hydrocortisone. In most cases, symptoms of adrenal insufficiency become serious enough that people seek medical treatment before an adrenal crisis occurs. However, sometimes symptoms appear for the first time during an adrenal crisis.

The danger signs of Addisonian crisis include:

- Extreme weakness, feeling terrible, vomiting, headache

- Light-headedness or dizziness on sitting up or standing up

- Feeling very cold, uncontrollable shaking; back, limb or abdominal pain

- Confusion, drowsiness, loss of consciousness

Addisonian crisis (adrenal crisis) the signs and symptoms may also include:

- Sudden, severe pain in your lower back, abdomen or legs

- Severe vomiting and diarrhea, leading to dehydration

- Low blood pressure

- Loss of consciousness

- High potassium (hyperkalemia) and low sodium (hyponatremia)

If this happens to yourself or someone you are caring for, do not delay. If not treated, an adrenal crisis can cause death:

- inject yourself (or the person you are caring for) with your hydrocortisone ampoule (100mg)

- seek immediate medical attention – call your local emergency services number, stating “Addisonian crisis”

- Other key phrases to use are: Steroid-dependent, risk of adrenal crisis, adrenal insufficiency crisis, Addison’s or Addisonian emergency

- AND describe symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, injury/shock).

Addisonian crisis requires immediate medical care – If not treated, an adrenal crisis can cause death.

In an Addisonian crisis you will also have:

- Low blood pressure (hypotension)

- High potassium (hyperkalemia) and low sodium (hyponatremia)

Adrenal crisis treatment typically includes intravenous injections of:

- Hydrocortisone

- Saline solution

- Sugar (dextrose)

In adrenal crisis, you need to be given the drug hydrocortisone right away through a vein (intravenous) or muscle (intramuscular). You may receive intravenous fluids if you have low blood pressure.

You will need to go to the hospital for treatment and monitoring. If infection or another medical problem caused the Addisonian crisis, you may need additional treatment.

The treatment of Addisonian crisis to prevent hypovolemic shock is:

- 100mg hydrocortisone, intravenous (preferably) or intramuscular

- Instructions for hydrocortisone 100mg:

- Use hydrocortisone sodium phosphate OR hydrocortisone sodium succinate, 100mg.

- Note that hydrocortisone acetate can NOT be used due to its slow-release, microcrystalline formulation.

- Give bolus hydrocortisone over a minimum of 10 minutes to avoid vascular damage.

- Instructions for hydrocortisone 100mg:

- An intravenous saline infusion.

Once this treatment has been administered, Addisonian crisis patient will require monitoring until their blood pressure and electrolytes are stable. Thus, you may continue to need:

- 100mg hydrocortisone every 6 hours intravenous or intramuscular

- OR by infusion pump, e.g. 200mg per 24 hours or 8.33mg per hour

- Usually, these high doses of hydrocortisone can be weaned to oral maintenance doses of hydrocortisone after 24 – 72 hours, provided the patient’s condition is improving. Ensure that patient is stable on oral steroids prior to discharge.

- An intravenous saline infusion (0.9% saline solution or equivalent).

How is adrenal crisis treated ?

Adrenal crisis is treated with adrenal hormones. People with adrenal crisis need immediate treatment. Any delay can cause death. When people with adrenal crisis are vomiting or unconscious and cannot take their medication, the hormones can be given as an injection.

A person with adrenal insufficiency should carry a corticosteroid injection at all times and make sure that others know how and when to administer the injection, in case the person becomes unconscious.

The dose of corticosteroid needed may vary with a person’s age or size. For example, a child younger than 2 years of age can receive 25 milligrams (mg), a child between 2 and 8 years of age can receive 50 mg, and a child older than 8 years should receive the adult dose of 100 mg.

How can a person prevent adrenal crisis ?

The following steps can help a person prevent adrenal crisis:

- Ask a health care provider about possibly having a shortage of adrenal hormones, if always feeling tired, weak, or losing weight.

- Learn how to increase the dose of corticosteroid for adrenal insufficiency when ill. Ask a health care provider for written instructions for sick days. First discuss the decision to increase the dose with the health care provider when ill.

- When very ill, especially if vomiting and not able to take pills, seek emergency medical care immediately.

How can someone with adrenal insufficiency prepare in case of an emergency ?

People with adrenal insufficiency should always carry identification stating their condition, “adrenal insufficiency,” in case of an emergency. A card or medical alert tag should notify emergency health care providers of the need to inject corticosteroids if the person is found severely injured or unable to answer questions.

The card or tag should also include the name and telephone number of the person’s health care provider and the name and telephone number of a friend or family member to be notified. People with adrenal insufficiency should always carry a needle, a syringe, and an injectable form of corticosteroids for emergencies.

What problems can occur with adrenal insufficiency ?

Problems can occur in people with adrenal insufficiency who are undergoing surgery, suffer a severe injury, have an illness, or are pregnant. These conditions place additional stress on the body, and people with adrenal insufficiency may need additional treatment to respond and recover.

Surgery

People with adrenal insufficiency who need any type of surgery requiring general anesthesia must be treated with IV corticosteroids and saline. IV treatment begins before surgery and continues until the patient is fully awake after surgery and is able to take medication by mouth. The “stress” dosage is adjusted as the patient recovers until the regular, presurgery dose is reached.

In addition, people who are not currently taking corticosteroids, yet have taken long-term corticosteroids in the past year, should tell their health care provider before surgery. These people may have sufficient ACTH for normal events; however, they may need IV treatment for the stress of surgery.

Severe Injury

Patients who suffer severe injury may need a higher, “stress” dosage of corticosteroids immediately following the injury and during recovery. Often, these stress doses must be given intravenously. Once the patient recovers from the injury, dosing is returned to regular, pre-injury levels.

Illness

During an illness, a person taking corticosteroids orally may take an adjusted dose to mimic the normal response of the adrenal glands to this stress on the body. Significant fever or injury may require a triple dose. Once the person recovers from the illness, dosing is then returned to regular, pre-illness levels. People with adrenal insufficiency should know how to increase medication during such periods of stress, as advised by their health care provider. Immediate medical attention is needed if severe infections, vomiting, or diarrhea occur. These conditions can lead to an adrenal crisis.

Pregnancy

Women with adrenal insufficiency who become pregnant are treated with the same hormone therapy taken prior to pregnancy. However, if nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy interfere with taking medication orally, injections of corticosteroids may be necessary. During delivery, treatment is similar to that of people needing surgery. Following delivery, the dose is gradually lessened, and the regular dose is reached about 10 days after childbirth.

Addison’s disease complications

Addison’s disease can develop into an adrenal crisis (Addisonian crisis) if not recognized and promptly treated. This can result in hypotension (low blood pressure), shock, hypoglycemia (low blood levels of sugar), acute cardiovascular decompensation, and death 25. Patients with adrenal insufficiency are also at higher risk of death due to infections, cancer, and cardiovascular causes. Delayed recognition and treatment of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) can cause neurologic consequences. A supraphysiologic glucocorticoid replacement can lead to the development of Cushing syndrome 26. Growth suppression can occur in children. Premature ovarian failure or primary ovarian insufficiency may develop in up to 10% of women with Addison disease 27.

Addisonian crisis

If you have untreated Addison’s disease, you may develop an Addisonian crisis as a result of physical stress, such as an injury, infection or illness. Normally, the adrenal glands produce two to three times the usual amount of cortisol in response to physical stress. With adrenal insufficiency, the inability to increase cortisol production with stress can lead to an Addisonian crisis.

An Addisonian crisis is a life-threatening situation that results in low blood pressure, low blood levels of sugar and high blood levels of potassium. You will need immediate medical care.

People with Addison’s disease commonly have associated autoimmune diseases.

Addison’s disease prevention

Addison’s disease can’t be prevented, but there are steps you can take to avoid an addisonian crisis:

- Talk to your doctor if you always feel tired, weak, or are losing weight. Ask about having an adrenal shortage.

- If you have been diagnosed with Addison’s disease, ask your doctor about what to do when you’re sick. You may need to learn how to increase your dose of corticosteroids.

- If you become very sick, especially if you are vomiting and you can’t take your medication, go to the emergency room.

Some people with Addison’s disease worry about serious side effects from hydrocortisone or prednisone because they know these occur in people who take these steroids for other reasons. However, if you have Addison’s disease, the adverse effects of high-dose glucocorticoids should not occur, since the dose you are prescribed is replacing the amount that is missing. Make sure to follow up with your doctor on a regular basis to make sure your dose is not too high.

Addison’s disease diagnosis

In its early stages, adrenal insufficiency can be difficult to diagnose. A health care provider may suspect it after reviewing a person’s medical history and symptoms.

A diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is confirmed through hormonal blood and urine tests. A health care provider uses these tests first to determine whether cortisol levels are too low and then to establish the cause. Imaging studies of the adrenal and pituitary glands can be useful in helping to establish the cause.

Your doctor will talk to you first about your medical history and your signs and symptoms. If your doctor thinks that you may have Addison’s disease, you may undergo some of the following tests:

- Blood test. Measuring your blood levels of sodium, potassium, cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) gives your doctor an initial indication of whether adrenal insufficiency may be causing your signs and symptoms. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce its hormones. A blood test can also measure antibodies associated with autoimmune Addison’s disease. Because the adrenal hormones are gradually lost over years to decades, the levels vary. One of the first indications that there is adrenal cortex dysfunction is an elevated plasma renin level 28. A rise in adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels is concomitant with the loss of adrenal hormones. Yearly monitoring of ACTH levels in at-risk individuals shows that measurements greater than 50 pg per mL (11 pmol per L), which exceed the upper limit of normal, are indicative of cortisol deficiency 15.

- Thyroid function test. Your thyroid gland may also be tested to see if it’s working properly. Your thyroid gland is found in your neck. It produces hormones that control your body’s growth and metabolism. People with Addison’s disease often have an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), where the thyroid gland does not produce enough hormones. By testing the levels of certain hormones in your blood, your endocrinologist (a specialist in hormone conditions) can determine whether you have hypothyroidism.

- ACTH (Cosyntropin) Stimulation Test. The ACTH (Cosyntropin) Stimulation Test is the most commonly used test for diagnosing adrenal insufficiency. In this test, the patient is given an intravenous (IV) injection of synthetic ACTH, and samples of blood, urine, or both are taken before and after the injection. The cortisol levels in the blood and urine samples are measured in a lab. The normal response after an ACTH injection is a rise in blood and urine cortisol levels. People with Addison’s disease or longstanding secondary adrenal insufficiency have little or no increase in cortisol levels.

- The serum cortisol, plasma ACTH, plasma aldosterone, and plasma renin levels should be measured before administering 250 mcg of ACTH. At 30 and 60 minutes after intravenous ACTH administration, the serum cortisol level should be measured again. A normal response occurs with peak cortisol levels greater than 18 to 20 mcg per dL (497 to 552 nmol per L); a smaller or absent response is diagnostic for adrenal insufficiency 29.

- Both low- and high-dose ACTH stimulation tests may be used depending on the suspected cause of adrenal insufficiency. For example, if secondary adrenal insufficiency is mild or has only recently occurred, the adrenal glands may still respond to ACTH because they have not yet shut down their own production of hormone. Some studies have suggested a low dose—1 microgram (mcg)—may be more effective in detecting secondary adrenal insufficiency because the low dose is still enough to raise cortisol levels in healthy people, yet not in people with mild or recent secondary adrenal insufficiency. However, recent research has shown that a significant proportion of healthy children and adults can fail the low-dose test, which may lead to unnecessary treatment. Therefore, some health care providers favor using a 250 mcg ACTH test for more accurate results.

- CRH stimulation test. When the response to the ACTH test is abnormal, a CRH (Corticotropin-releasing hormone) stimulation test can help determine the cause of adrenal insufficiency. In this test, the patient is given an IV injection of synthetic CRH (Corticotropin-releasing hormone) and blood is taken before and 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after the injection. The cortisol levels in the blood samples are measured in a lab. People with Addison’s disease respond by producing high levels of ACTH, yet no cortisol. People with secondary adrenal insufficiency do not produce ACTH or have a delayed response. CRH will not stimulate ACTH secretion if the pituitary is damaged, so no ACTH response points to the pituitary as the cause. A delayed ACTH response points to the hypothalamus as the cause.

- Insulin-induced hypoglycemia test. Occasionally, doctors suggest this test if pituitary disease is a possible cause of adrenal insufficiency (secondary adrenal insufficiency). The test involves checking your blood sugar (blood glucose) and cortisol levels at various intervals after an injection of insulin. In healthy people, glucose levels fall and cortisol levels increase.

- Ultrasound of the abdomen. Ultrasound uses a device, called a transducer, that bounces safe, painless sound waves off organs to create an image of their structure. A specially trained technician performs the procedure in a health care provider’s office, an outpatient center, or a hospital, and a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the images; a patient does not need anesthesia. The images can show abnormalities in the adrenal glands, such as enlargement or small size, nodules, or signs of calcium deposits, which may indicate bleeding.

- Tuberculin skin test. A tuberculin skin test measures how a patient’s immune system reacts to the bacteria that cause tuberculosis. A small needle is used to put some testing material, called tuberculin, under the skin. A nurse or lab technician performs the test in a health care provider’s office; a patient does not need anesthesia. In 2 to 3 days, the patient returns to the health care provider, who will check to see if the patient had a reaction to the test. The test can show if adrenal insufficiency could be related to tuberculosis.To test whether a person has tuberculosis (TB) infection, which is when tuberculosis bacteria live in the body without making the person sick, a special tuberculosis (TB) blood test is used. To test whether a person has tuberculosis (TB) disease, which is when tuberculosis bacteria are actively attacking a person’s lungs and making the person sick, other tests such as a chest x-ray and a sample of sputum—phlegm that is coughed up from deep in the lungs—may be needed.

- Antibody blood tests. The antibody blood test can detect antibodies—proteins made by the immune system to protect the body from foreign substances—associated with autoimmune Addison’s disease. Measurement of 21-hydroxylase antibody levels helps discern the cause of Addison disease. The 21-hydroxylase enzyme is necessary for cortisol synthesis in the adrenal cortex; antibodies directed against the 21-hydroxylase enzyme (21-hydroxylase antibodies are present in more than 90% of recent-onset cases) are specific for autoimmune Addison’s disease and are detectable before symptom onset by years to decades 14.

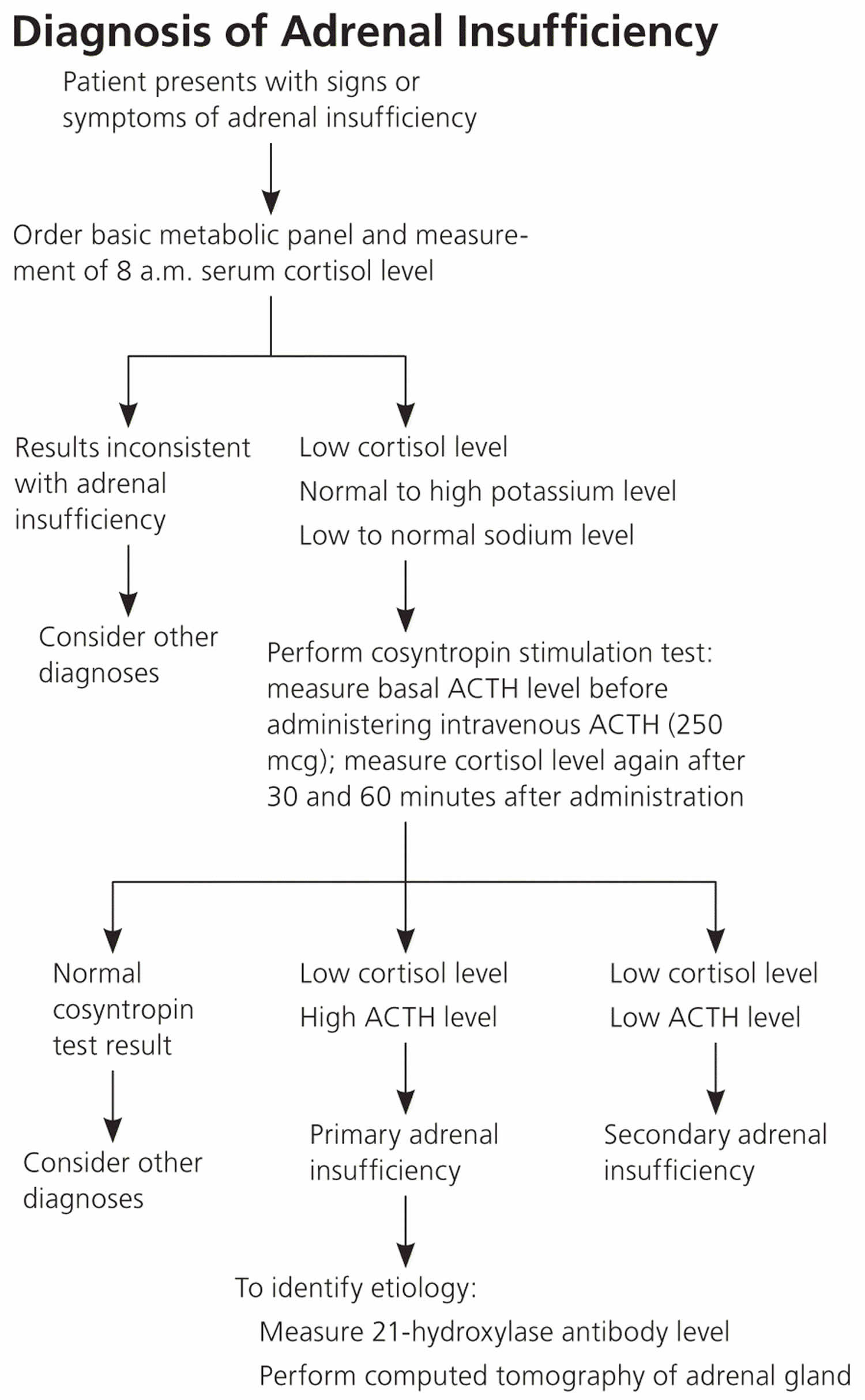

The goal of laboratory testing is to document a low cortisol level and determine whether the adrenal insufficiency is primary or secondary, as outlined in Figure 6. Low serum cortisol levels at 8 a.m. (less than 3 mcg per dL [83 nmol per L]) suggest adrenal insufficiency, as do levels 30. Hyponatremia (low blood sodium) can be attributed to cortisol and mineralocorticoid deficiencies, whereas hyperkalemia (high blood potassium) is attributed solely to a lack of mineralocorticoids.

After secondary adrenal insufficiency is diagnosed, health care providers may use the following tests to obtain a detailed view of the pituitary gland and assess how it is functioning:

- Imaging tests. Your doctor may have you undergo a computerized tomography (CT) scan of your abdomen to check the size of your adrenal glands and look for other abnormalities that may give insight to the cause of the adrenal insufficiency. Your doctor may also suggest an MRI scan of your pituitary gland if testing indicates you might have secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Figure 6. Addison’s disease diagnosis

Addison’s disease treatment

All treatment for Addison’s disease involves hormone replacement therapy (glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids), you’ll need to take daily prescription hormones to replace the lost hormones to correct the levels of steroid hormones your body isn’t producing.

This can include hydrocortisone, prednisone, or cortisone acetate. If your body is not making enough of the hormone aldosterone, your doctor may prescribe fludrocortisone. These medicines are taken every day by mouth (in pill form). This should help you to live an active life, although many people find they still need to manage their fatigue.

Your doctor may also recommend that you take a medicine called dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a precursor hormone, which means it has little biological effect on its own, but has powerful effects when converted into sex hormones such as testosterone and estradiol. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is produced from cholesterol mainly by the outer layer of the adrenal glands (the adrenal cortex), although it is also made by the testes and ovaries in small amounts. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) circulates in the blood, mainly attached to sulphur as dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, which prevents the hormone being broken down. In women, dehydroepiandrosterone is an important source of estrogens in the body – it provides about 75% of estrogens before the menopause, and 100% of estrogens in the body after menopause. Some women who have Addison’s disease find that taking this medicine improves their mood and sex drive.

The dose of each medication is adjusted to meet the needs of the patient.

In some cases, the underlying causes of Addison’s disease can be treated. For example, tuberculosis (TB) is treated with a course of antibiotics over a period of at least 6 months.

However, most cases are caused by a problem with the immune system that cannot be cured.

If you are experiencing an Addisonian crisis, you need immediate medical care. The treatment typically consists of intravenous (IV) injections of hydrocortisone, saline (salt water), and dextrose (sugar). These injections help restore blood pressure, blood sugar, and potassium levels to normal.

During adrenal crisis, low blood pressure, low blood glucose, low blood sodium, and high blood levels of potassium can be life threatening. Standard therapy involves immediate IV injections of corticosteroids and large volumes of IV saline solution with dextrose, a type of sugar. This treatment usually brings rapid improvement. When the patient can take liquids and medications by mouth, the amount of corticosteroids is decreased until a dose that maintains normal hormone levels is reached. If aldosterone is deficient, the person will need to regularly take oral doses of fludrocortisone acetate.

Researchers have found that using replacement therapy for dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in adolescent girls who have secondary adrenal insufficiency and low levels of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) can improve pubic hair development and psychological stress. Further studies are needed before routine supplementation recommendations can be made.

Cortisol is replaced with a corticosteroid, such as hydrocortisone, prednisone, or dexamethasone, taken orally one to three times each day, depending on which medication is chosen. Dexamethasone is not an appropriate choice for maintenance treatment; the dose titration is difficult and increases the risk of Cushing’s syndrome 31.

If aldosterone is also deficient, it is replaced with oral doses of a mineralocorticoid hormone, called fludrocortisone acetate (Florinef), taken once or twice daily. People with secondary adrenal insufficiency normally maintain aldosterone production, so they do not require aldosterone replacement therapy.

An ample amount of sodium is recommended, especially during heavy exercise, when the weather is hot or if you have gastrointestinal upsets, such as diarrhea. If you feel unwell due to salt deficiency, such as light-headedness, cramps or feeling generally washed out, to feel better quickly you will need to take some salt (soup and salty crackers or sodium tablets). Your doctor will also suggest a temporary increase in your dosage if you’re facing a stressful situation, such as an operation, an infection or a minor illness. If you overdose on salt or fludrocortisone, you will notice that your feet and ankles become puffy. This is a reliable sign in most people and it may mean you need to reduce your fludrocortisone dose, although this should only be done after consulting your endocrinologist. One other thing to watch out for is liquorice, which interacts with your medications to produce salt-retention in the same way as aldosterone does. People with Addison’s disease need to avoid liquorice for this reason.

Table 3. Medications for the treatment of Addison disease

| Medication | Dosage | Comments | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | |||

| Prednisone | 3 to 5 mg once daily | Use stress doses for illness, surgical procedures, and hospitalization | Symptoms of adrenal insufficiency; low to normal plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone levels indicate over-replacement |

| Hydrocortisone | 15 to 25 mg divided into two or three doses per day | Use stress doses for illness, surgical procedures, and hospitalization | |

| Dexamethasone | 0.5 mg once daily | Use intramuscular dose for emergencies and when unable to tolerate oral intake | |

| Mineralocorticoid | |||

| Fludrocortisone | 0.05 to 0.2 mg once daily | Dosage may need to increase to 0.2 mg per day in the summer because of salt loss from perspiration | Blood pressure; serum sodium and potassium levels; plasma renin activity in the upper normal range |

| Androgen | |||

| Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) | 25 to 50 mg once daily | Available as an over-the-counter supplement; can improve mood and quality of life in women | Libido, mood, and sense of well-being |

Some options for treatment include:

- Oral corticosteroids. Hydrocortisone (Cortef), prednisone or cortisone acetate may be used to replace cortisol. Your doctor may prescribe fludrocortisone to replace aldosterone.

- Glucocorticoids:

- Hydrocortisone 5 to 25 mg/day (can be divided into 2 or 3 doses)

- Prednisone 3 to 5 mg/day

- To minimize adverse effects, the glucocorticoid dose should be titrated to the lowest possible dose that controls symptoms; ensure the patient is clinically well. Plasma Renin level can also be used to adjust the doses. Serum ACTH levels may vary significantly and cannot be used for dose adjustment. It is important to consider concurrent medications when deciding the glucocorticoid dose. For example, certain drugs such as Rifampin can increase hepatic glucocorticoid metabolism and may inactivate cortisol 25.

- Mineralocorticoid: Fludrocortisone 0.05 to 0.2 mg daily.

- Fludrocortisone should be administered at a sufficient dose to keep the plasma renin level in the reference range 32. An elevated plasma renin level indicates a higher dose of fludrocortisone is required. The mineralocorticoid dosage should also be tailored to address the degree of stress. Furthermore, the identification and treatment of underlying causes such as sepsis are critical for an optimal outcome.

- Glucocorticoids:

- Corticosteroid injections. If you’re ill with vomiting and can’t retain oral medications, injections may be needed.

Treatment considerations

- In patients with Addison’s disease, glucocorticoid secretion does not increase during stress. Patients should be counseled about the need for stress-dose glucocorticoids for illnesses and before surgical procedures because destruction of the adrenal glands prevents an adequate physiologic response to stress 33. Therefore, in the presence of fever, infection, or other illnesses, the hydrocortisone dose should be increased to compensate for a possible stress response.

- Mineralocorticoid replacement generally does not need to be changed for illness or procedures. However, the dose may need to be adjusted in the summer months when there is salt loss from excessive perspiration.

- There are many expert recommendations for stress dosing of glucocorticoids based on the degree of stress; clinical trials comparing different approaches are lacking in the literature. In general, a usual stress dose is 2-3 times the daily maintenance dose 34. For minor illnesses such as influenza or viral gastroenteritis, the patient can take three times the glucocorticoid dose during the illness and resume normal dosing after resolution of symptoms.

- Patients should also have an injectable form of glucocorticoid (intramuscular dexamethasone) available in cases of nausea, vomiting, or other situations when oral intake is not possible.

- Patients taking rifampin require an increased dose of hydrocortisone, as it increases the clearance of hydrocortisone.

- Thyroid hormone therapy in persons with undiagnosed Addison disease may precipitate an adrenal crisis because the thyroid hormone increases the hepatic clearance of cortisol 8. In addition, patients with a new diagnosis can have a reversible increase in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels because glucocorticoids inhibit secretion 35. Glucocorticoid replacement can potentially normalize thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels less than 30 mIU/L 8. In individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus, unexplained hypoglycemia and decreasing insulin requirements may be the initial signs of Addison disease 36.

- In patients with concomitant diabetes insipidus, glucocorticoid therapy can aggravate diabetes insipidus. Cortisol is required for free-water clearance, and cortisol deficiency may prevent polyuria.

- Pregnancy, particularly during the third trimester, increases corticosteroid requirements.

Potential future treatments

Researchers are working to develop delayed-release corticosteroids, which act more like the human body. They are also working on pumps implanted under the skin that can deliver steroids in more-accurate doses.

Future treatment may eventually involve using adrenocortical stem cells combined with immunomodulatory treatment — modifying the immune response or the immune system — as well as gene therapy.

Adjusting your medication

At certain times, your medication may need to be adjusted to account for any additional strain on your body. For example, you may need to increase the dosage of your medication if you experience any of the following:

- an illness or infection – particularly if you have a high temperature of 38 °C or above

- an accident, such as a car crash

- an operation, dental or medical procedure – such as a tooth filling or endoscopy

- strenuous exercise that’s not usually part of your daily life

This will help your body cope with the additional stress. Your endocrinologist will monitor your dosage and advise about any changes.

Over time, as you get used to the condition and learn what can trigger your symptoms, you may learn how to adjust your medication yourself. However, always consult your doctor or specialist if you’re unsure.

Get a hydrocortisone emergency injection kit

After your Addison’s disease diagnosis, you should be issued with a prescription for the medication required for a hydrocortisone emergency injection kit. This will include vials of hydrocortisone that either you or a friend or family member can administer if you are vomiting and unable to absorb oral tablets, or showing other signs of severe illness.

There are two types of hydrocortisone available. These are prescribed as 3 – 5 vials. You will be prescribed either:

- Hydrocortisone sodium phosphate 100mg (1ml liquid ampoule), OR

- Hydrocortisone sodium succinate 100mg (powdered Solu-Cortef plus 2ml water ampoule)

You will also need the necessary intramuscular needles and syringes needed to inject.

Many people prefer hydrocortisone sodium phosphate (ex-Efcortesol) for their injection kits as this requires no mixing, before drawing up into the needle for injection. However if this is unavailable you should swap temporarily to Solu-Cortef which is a dried form of hydrocortisone that is mixed with a water vial before injection. The ‘How-To’ leaflets for your kit and instructions below cover both types of hydrocortisone medication for injection.

Emergency treatment

You and a partner or family member may be trained to administer an injection of hydrocortisone in an emergency.

This could be necessary if you go into shock after an injury, or if you experience vomiting or diarrhea and are unable to keep down oral medication. This may occur if you’re pregnant and have morning sickness. Your endocrinologist will discuss with you when an injection might be necessary.

If you need to administer emergency hydrocortisone, always call your doctor immediately afterwards. Check what out-of-hours services are available in your local area, in case the emergency is outside normal working hours.

You can also register yourself with your local ambulance service, so they have a record of your requirement for a steroid injection or tablets, if you need their assistance.

Treating adrenal crisis

Adrenal crisis, or Addisonian crisis, needs urgent medical attention. Dial your local emergency services number for an ambulance if you or someone you know are experiencing adrenal crisis.

Signs of an adrenal crisis include:

- severe dehydration

- pale, cold, clammy skin

- sweating

- rapid, shallow breathing

- dizziness

- severe vomiting and diarrhea

- severe muscle weakness

- headache

- severe drowsiness or loss of consciousness

In hospital, you’ll be given lots of fluid through a vein in your arm to rehydrate you. This will contain a mixture of salts and sugars (sodium, glucose and dextrose) to replace what your body is lacking. You’ll also be injected with hydrocortisone to replace the missing cortisol hormone.

Any underlying causes of the adrenal crisis, such as an infection, will also be treated.

Addison’s disease diet

Some people with Addison’s disease who are aldosterone deficient can benefit from following a diet rich in sodium. A health care provider or a dietitian can give specific recommendations on appropriate sodium sources and daily sodium guidelines if necessary.

Corticosteroid treatment is linked to an increased risk of osteoporosis—a condition in which the bones become less dense and more likely to fracture. People who take corticosteroids should protect their bone health by consuming enough dietary calcium and vitamin D. A health care provider or a dietitian can give specific recommendations on appropriate daily calcium intake based upon age and suggest the best types of calcium supplements, if necessary.

Coping and support

These steps may help you cope better with a medical emergency if you have Addison’s disease:

- Carry a medical alert card and bracelet at all times. In the event you’re incapacitated, emergency medical personnel know what kind of care you need.

- Keep extra medication handy. Because missing even one day of therapy may be dangerous, it’s a good idea to keep a small supply of medication at work, at a vacation home and in your travel bag, in the event you forget to take your pills. Also, have your doctor prescribe a needle, syringe and injectable form of corticosteroids to have with you in case of an emergency.

- Stay in contact with your doctor. Keep an ongoing relationship with your doctor to make sure that the doses of replacement hormones are adequate, but not excessive. If you’re having persistent problems with your medications, you may need adjustments in the doses or timing of the medications.

Living with Addison’s disease

Many people with Addison’s disease find that taking their medication enables them to continue with their normal diet and exercise routines. However, bouts of fatigue are also common, and it can take some time to learn how to manage these periods of low energy.

Some people find that needing to take regular doses of medication is restrictive and affects their daily life or emotional health. Missing a dose of medication, or taking it late, can also lead to exhaustion or insomnia.

Some people can develop associated health conditions, such as diabetes or an underactive thyroid, which require extra treatment and management.

You’ll usually need to have appointments with an endocrinologist every 6 to 12 months so they can review your progress and adjust your medication dose, if necessary. Your doctor can provide support and repeat prescriptions in between these visits.

Failing to take your medication could lead to a serious condition called an adrenal crisis, so you must:

- remember to collect your repeat prescriptions

- keep spare medication as necessary – for example, in the car or at work, and always carry some spare medication with you

- take your medication every day at the right time

- pack extra medication if you’re going away – usually double what you would normally need, plus your injection kit

- carry your medication in your hand luggage if you are traveling by plane, with a note from your doctor explaining why it is necessary

You could also inform close friends or colleagues of your condition. Tell them about the signs of adrenal crisis and what they should do if you experience one.

Medical alert bracelets

It’s also a good idea to wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace that informs people you have Addison’s disease. Medical alert bracelets or necklaces are pieces of jewellery engraved with your medical condition and an emergency contact number. They are available from a number of retailers.

Wearing a medical alert bracelet will inform any medical staff treating you about your condition and what medication you require.

After a serious accident, such as a car crash, a healthy person produces more cortisol. This helps you cope with the stressful situation and additional strain on your body that results from serious injury. As your body cannot produce cortisol, you’ll need a hydrocortisone injection to replace it and prevent an adrenal crisis.

Addison’s disease prognosis

The treatment of Addison’s disease is a life-long replacement of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. A strict balance is required to avoid over-or under-treatment with glucocorticoids. Therefore, careful monitoring is required. Over-treatment with glucocorticoids may result in obesity, diabetes, and osteoporosis 37. Over-treatment with mineralocorticoids can cause hypertension (high blood pressure). Patients with Addison disease are at increased risk of developing other autoimmune conditions; up to 50% of patients with Addison disease may develop another autoimmune condition 38. Thyroid hormone replacement may precipitate an adrenal crisis in unrecognized patients.

References- Adrenal Insufficiency. https://www.hormone.org/diseases-and-conditions/adrenal/adrenal-insufficiency

- Betterle C, Morlin L. Autoimmune Addison’s disease. In: Ghizzoni L, Cappa M, Chrousos G, Loche S, Maghnie M, eds. Pediatric Adrenal Diseases. Endocrine Development. Vol. 20. Padova, Italy: Karger Publishers; 2011: 161–172.

- Erichsen MM, Løvås K, Skinningsrud B, et al. Clinical, immunological, and genetic features of autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency: observations from a Norwegian registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4882–4890.

- Bleicken B, Hahner S, Ventz M, Quinkler M. Delayed diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is common: a cross-sectional study in 216 patients. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(6):525–531.

- Bouachour G, Tirot P, Varache N, Gouello JP, Harry P, Alquier P. Hemodynamic changes in acute adrenal insufficiency. Intensive Care Med. 1994; 20(2):138–141.

- Stewart PM, Krone NP. The adrenal cortex. In: Kronenburg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Reed Larson P, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. pp. 515–20. Ch. 15.

- The conquest of Addison’s disease. Hiatt JR, Hiatt N. Am J Surg. 1997 Sep; 174(3):280-3.

- Addison Disease: Early Detection and Treatment Principles. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Apr 1;89(7):563-568. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2014/0401/p563.html

- Burke CW. Adrenocortical insufficiency. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;14(4):947–976.

- Ross AP, Ben-Zacharia A, Harris C, Smrtka J. Multiple Sclerosis, Relapses, and the Mechanism of Action of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone. Frontiers in Neurology. 2013;4:21. doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3591751/

- Burton, C., Cottrell, E., & Edwards, J. (2015). Addison’s disease: identification and management in primary care. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 65(638), 488–490. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X686713

- Neary N, Nieman L. Adrenal insufficiency: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2010;(3):217–223.

- Eisenbarth GS, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(20):2068–2079.

- Betterle C, Dal Pra C, Mantero F, Zanchetta R. Autoimmune adrenal insufficiency and autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes: autoantibodies, autoantigens, and their applicability in diagnosis and disease prediction [published correction appears in Endocr Rev. 2002;23(4):579]. Endocr Rev. 2002;23(3):327–364.

- Baker PR, Nanduri P, Gottlieb PA, et al. Predicting the onset of Addison’s disease: ACTH, renin, cortisol, and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(5):617–624.

- Zelissen PM, Bast EJ, Croughs RJ. Associated autoimmunity in Addison’s disease. J Autoimmun. 1995;8(1):121–130.

- Husebye ES, Løvås K. Immunology of Addison’s disease and premature ovarian failure. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2009;38(2):389–405.

- Baker V. Life plans and family-building options for women with primary ovarian insufficiency. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(4):362–372.

- O’Leary C, Walsh CH, Wieneke P, et al. Coeliac disease and autoimmune Addison’s disease: a clinical pitfall. QJM. 2002;95(2):79–82.

- Kasperlik-Zaluska AA, Migdalska B, Czarnocka B, Drac-Kaniewska J, Niegowska E, Czech W. Association of Addison’s disease with autoimmune disorders—a long-term observation of 180 patients. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67(793):984–987.

- Blizzard RM, Chee D, Davis W. The incidence of adrenal and other antibodies in the sera of patients with idiopathic adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease). Clin Exp Immunol. 1967;2(1):19–30.

- Nerup J. Addison’s disease—clinical studies. A report of 108 cases. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1974;76(1):127–141.

- Collin P, Kaukinen K, Välimäki M, Salmi J. Endocrinological disorders and celiac disease. Endocr Rev. 2002 Aug;23(4):464-83. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0035

- Thompson Bastin, M. L., Baker, S. N., & Weant, K. A. (2014). Effects of etomidate on adrenal suppression: a review of intubated septic patients. Hospital pharmacy, 49(2), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1310/hpj4902-177

- Munir S, Quintanilla Rodriguez BS, Waseem M. Addison Disease. [Updated 2021 May 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441994

- Bornstein, S. R., Allolio, B., Arlt, W., Barthel, A., Don-Wauchope, A., Hammer, G. D., Husebye, E. S., Merke, D. P., Murad, M. H., Stratakis, C. A., & Torpy, D. J. (2016). Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 101(2), 364–389. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-1710

- Hoek A, Schoemaker J, Drexhage HA. Premature ovarian failure and ovarian autoimmunity. Endocr Rev. 1997 Feb;18(1):107-34. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0291

- Betterle C, Scalici C, Presotto F, et al. The natural history of adrenal function in autoimmune patients with adrenal autoantibodies. J Endocrinol. 1988;117(3):467–475.

- Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, et al. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72(4):773–778.

- Schmidt IL, Lahner H, Mann K, Petersenn S. Diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency: evaluation of the corticotropin-releasing hormone test and basal serum cortisol in comparison to the insulin tolerance test in patients with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(9):4193–4198.

- Arlt, W., & Society for Endocrinology Clinical Committee (2016). SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY ENDOCRINE EMERGENCY GUIDANCE: Emergency management of acute adrenal insufficiency (adrenal crisis) in adult patients. Endocrine connections, 5(5), G1–G3. https://doi.org/10.1530/EC-16-0054

- Oelkers W, Diederich S, Bähr V. Diagnosis and therapy surveillance in Addison’s disease: rapid adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) test and measurement of plasma ACTH, renin activity, and aldosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992 Jul;75(1):259-64. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1320051

- Oelkers W, Diederich S, Bähr V. Therapeutic strategies in adrenal insufficiency. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2001;62(2):212–216.

- Michels A, Michels N. Addison disease: early detection and treatment principles. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Apr 1;89(7):563-8.

- Samuels MH. Effects of variations in physiological cortisol levels on thyrotropin secretion in subjects with adrenal insufficiency: a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(4):1388–1393.

- Armstrong L, Bell PM. Addison’s disease presenting as reduced insulin requirement in insulin dependent diabetes. BMJ. 1996;312(7046):1601–1602.

- Chantzichristos D, Eliasson B, Johannsson G. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE Disease burden and treatment challenges in patients with both Addison’s disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020 Jul;183(1):R1-R11. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0052

- Zelissen PM, Bast EJ, Croughs RJ. Associated autoimmunity in Addison’s disease. J Autoimmun. 1995 Feb;8(1):121-30. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1995.0009