Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative brain disease and is the most common cause of a progressive dementia in older people characterized by the accumulation of toxic, misfolded beta-amyloid proteins that form plaques in the brain. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis requires that beta-amyloid plaques accumulate to a specific level that is likely to cause symptoms including dementia. Dementia describes a group of symptoms affecting memory, thinking and social abilities severely enough to interfere with your daily life. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines dementia as “a loss of thinking, remembering, and reasoning skills that interferes with a person’s daily life and activities.” Other forms include frontotemporal degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, and vascular and mixed dementias. Dementia isn’t a specific disease, but several different diseases may cause dementia. Though dementia generally involves memory loss, memory loss has different causes. Having memory loss alone doesn’t mean you have dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive disorder that causes brain cells to waste away (degenerate) and die. It first involves the parts of the brain that control thought, memory and language. Memory problems are typically one of the first warning signs of cognitive loss, though initial symptoms may vary from person to person. A decline in other aspects of thinking, such as finding the right words, vision/spatial issues, and impaired reasoning or judgment, may also signal the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease cause a continuous decline in thinking, behavioral and social skills that disrupts a person’s ability to function independently. People with Alzheimer’s disease may have trouble remembering things that happened recently or names of people they know. As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, a person with Alzheimer’s disease will develop severe memory impairment and lose the ability to carry out everyday tasks like driving a car, cooking a meal, or paying bills. They may ask the same questions over and over, get lost easily, lose things or put them in odd places, and find even simple things confusing. As the disease progresses, some people become worried, angry, or violent. A related problem, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) causes more memory problems than normal for people of the same age. Many, but not all, people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) will develop Alzheimer’s disease.

In Alzheimer’s disease, over time, symptoms get worse. People may not recognize family members. They may have trouble speaking, reading or writing. They may forget how to brush their teeth or comb their hair. Later on, they may become anxious or aggressive, or wander away from home. Eventually, they need total care. This can cause great stress for family members who must care for them.

The most common type of Alzheimer’s disease usually begins after age 65 (late-onset Alzheimer’s disease). Alzheimer’s disease usually begins after age 60. However, Alzheimer’s disease is not a normal part of aging, though the risk goes up as you get older. Your risk is also higher if a family member has had the disease. Furthermore, younger-onset also known as early-onset Alzheimer’s disease affects people younger than age 65. Up to 5 percent (1 in every 20 people) of the more than 6 million Americans with Alzheimer’s disease have early- or young-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

There is currently no known cure for Alzheimer’s disease. No treatment can stop Alzheimer’s disease. However, some drugs may help keep symptoms from getting worse for a limited time.

Current Alzheimer’s disease medications may temporarily improve symptoms or slow the rate of decline. These treatments can sometimes help people with Alzheimer’s disease maximize function and maintain independence for a time. Different programs and services can help support people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers.

There is no treatment that cures Alzheimer’s disease or alters the disease process in the brain. In advanced stages of the disease, complications from severe loss of brain function — such as dehydration, malnutrition or infection — result in death.

A number of conditions, including treatable conditions, can result in memory loss or other dementia symptoms. If you are concerned about your memory or other thinking skills, talk to your doctor for a thorough assessment and diagnosis.

If you are concerned about thinking skills you observe in a family member or friend, talk about your concerns and ask about going together to a doctor’s appointment.

Alzheimer’s disease cause

Scientists do not yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer’s disease. There probably is not one single cause, but several factors that affect each person differently. Scientists believe that for most people, Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors that affect the brain over time.

- Age is the best known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. As you age, biological processes can become dysfunctional and contribute to Alzheimer’s. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia increases with age, affecting an estimated 1 in 14 people over the age of 65 and 1 in every 6 people over the age of 80.

- Inflammation is a part of your normal immune response and helps prevent infection. Inflammation can be both protective and harmful. But chronic inflammation can damage your neurons. When you are young, inflammation ramps up and then subsides quickly. But as you get older, it takes longer to reset, meaning you stay inflamed even when your body is healthy.

- Family history—researchers believe that genetics may play a role in developing Alzheimer’s disease. Familial Alzheimer’s disease also known as early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is a very rare form of the disease caused by a gene mutation inherited from a parent. It involves single gene mutations on chromosomes 1, 14, or 21. There are no genetic “causes” of the more common late-onset form of Alzheimer’s. Though genes such as APOE4 (apolipoprotein E4) can increase a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, they don’t mean you will get it. Epigenetic factors, which influence how much or how little your genes are expressed, can also contribute by turning up “bad” genes or turning down “good” ones.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction. Your brain accounts for about 2% of your body weight but use 20% of your body’s energy. This energy comes from glucose, and brain’s ability to process and use it can become less efficient with age, which starves your neurons. Some of this can stem from dysfunction in your mitochondria, which are the engines that power your cells. Diabetes exacerbates this problem, which is why it is a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

- Oxidation. During our lives, we are exposed to various things in the environment that can damage our DNA and proteins. Free radicals, the sun, pollution—these all contribute to oxidation and cellular stress. Our ability to repair such cellular damage wanes as we get older.

- Changes in the brain can begin years before the first symptoms appear.

- Researchers are studying whether education, diet, and environment play a role in developing Alzheimer’s disease.

- Scientists are finding more evidence that some of the risk factors for heart disease and stroke, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol may also increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Damage to the body’s blood vessel network can limit the brain’s supply of oxygen and vital nutrients needed for cells to work properly. Neurons are particularly vulnerable due to their significant energy needs. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease are major risk factors for Alzheimer’s because of their negative impact on your vasculature.

- There is growing evidence that physical, mental, and social activities may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Less than 1 percent of the time, Alzheimer’s disease is caused by specific genetic changes that virtually guarantee a person will develop the disease. These rare occurrences usually result in disease onset in middle age.

The exact causes of Alzheimer’s disease aren’t fully understood, but at its core are problems with brain proteins that fail to function normally, disrupt the work of brain cells (neurons) and unleash a series of toxic events. Neurons are damaged, lose connections to each other and eventually die.

The damage most often starts in the region of the brain that controls memory, but the process begins years before the first symptoms. The loss of neurons spreads in a somewhat predictable pattern to other regions of the brains. By the late stage of the disease, the brain has shrunk significantly.

Researchers are focused on the role of two proteins:

- Plaques. Beta-amyloid is a leftover fragment of a larger protein. When these fragments cluster together, they appear to have a toxic effect on neurons and to disrupt cell-to-cell communication. These clusters form larger deposits called amyloid plaques, which also include other cellular debris.

- Tangles. Tau proteins play a part in a neuron’s internal support and transport system to carry nutrients and other essential materials. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau proteins change shape and organize themselves into structures called neurofibrillary tangles. The tangles disrupt the transport system and are toxic to cells.

Proteins are critical to your survival, as they carry out most functions in your cells. Proteostasis is the “quality control” system for your proteins, which is responsible for their correct formation and for recycling them after they are no longer needed. Both sides of this system are more likely to malfunction as you get older, resulting in an excess of toxic, misfolded proteins such as beta-amyloid and tau proteins, respectively, accumulate into plaques and tangles. Other proteins that can be involved in Alzheimer’s include alpha-synuclein (a component of Lewy bodies), and TDP-43.

Although it’s not known exactly what causes this process to begin, scientists now know that it begins many years before symptoms appear. As brain cells become affected, there’s also a decrease in chemical messengers (called neurotransmitters) involved in sending messages, or signals, between brain cells. Levels of one neurotransmitter, acetylcholine (ACh), are particularly low in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Over time, different areas of the brain shrink. The first areas usually affected are responsible for memories. In more unusual forms of Alzheimer’s disease, different areas of the brain are affected. The first symptoms may be problems with vision or language rather than memory.

Risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s disease

Although it’s still unknown what triggers Alzheimer’s disease, several factors are known to increase your risk of developing the disease.

Age

Increasing age is the greatest known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s is not a part of normal aging, but as you grow older the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease increases. The likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease doubles every 5 years after you reach 65.

Around 1 in 20 people under 65 develop the early- or young-onset Alzheimer’s disease. This is early- or young-onset Alzheimer’s disease can affect people from around the age of 40.

One study, for example, found that annually there were two new diagnoses per 1,000 people ages 65 to 74, 11 new diagnoses per 1,000 people ages 75 to 84, and 37 new diagnoses per 1,000 people age 85 and older.

Young-onset Alzheimer’s disease

A very small percentage of people who develop Alzheimer’s disease have the young-onset type. Signs and symptoms of this type usually appear between ages 30 and 60 years. This type of Alzheimer’s disease is very strongly linked to your genes.

Scientists have identified three genes in which mutations cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. If you inherit one of these mutated genes from either parent, you will probably have Alzheimer’s symptoms before age 65. The genes involved are:

- Amyloid precursor protein (APP)

- Presenilin 1 (PSEN1)

- Presenilin 2 (PSEN2)

Mutations of these genes cause the production of excessive amounts of a toxic protein fragment called amyloid-beta peptide. This peptide can build up in the brain to form clumps called amyloid plaques, which are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. A buildup of toxic amyloid-beta peptide and amyloid plaques may lead to the death of nerve cells and the progressive signs and symptoms of this disorder.

As amyloid plaques collect in the brain, tau proteins malfunction and stick together to form neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles are associated with the abnormal brain functions seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

However, some people who have early-onset Alzheimer’s don’t have mutations in these three genes. That suggests that some early-onset forms of Alzheimer’s disease are linked to other genetic mutations or other factors that haven’t been identified yet.

One of the active research trials is the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN), which studies individuals with dominant Alzheimer’s mutations (PSEN1, PSEN2 or APP). This research network includes observational studies and clinical trials.

Family history and genetics

Your risk of developing Alzheimer’s is somewhat higher if a first-degree relative — your parent or sibling — has the disease. While a quarter of Alzheimer’s patients have a strong family history of the disease, only 1% directly inherit a gene mutation that causes early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, also known as familial Alzheimer’s disease 1. Most genetic mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease among families remain largely unexplained, and the genetic factors are likely complex.

Genes control the function of every cell in your body. Some genes determine your basic characteristics, such as the color of your eyes and hair. Other genes can make you more likely to develop certain diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease. The most common gene associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is a risk gene called apolipoprotein E (APOE). Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a regulator of lipid metabolism that has an affinity for beta-amyloid protein and is another genetic marker that increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. There are three types of the APOE gene, called alleles: APOE e2, e3 and e4. Because you inherit one APOE gene from your mother and another from your father, you have two copies of the APOE gene. Everyone has two copies of the gene and the combination determines your APOE “genotype”—E2/E2, E2/E3, E2/E4, E3/E3, E3/E4, or E4/E4.

- APOE e2 — rarest form of APOE and carrying even one copy appears to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease by up to 40%.

- APOE e3 — the most common allele and doesn’t seem to affect the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- APOE e4 — a little more common and is present in approximately 10-15% of the general population (located on chromosome 19) and it increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with getting the disease at an earlier age. Having one copy of E4 (E3/E4) can increase your risk by 2 to 3 times while two copies (E4/E4) can increase the risk by 12 times 2. APOE4 is just one of many risk factors for dementia and its influence can vary across age, gender, race, and nationality 3. For example, having one copy of the E4 allele may pose more risk to women while having two copies seems to affect men and women similarly 4.

Having at least one APOE e4 gene increases your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease two to threefold. If you have two APOE e4 genes, your risk is even higher, approximately eight to twelvefold. But not everyone who has one or even two APOE e4 genes develops Alzheimer’s disease. And the disease occurs in many people who don’t even have an APOE e4 gene, suggesting that the APOE e4 gene affects risk but is not a cause. Other genetic and environmental factors likely are involved in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

As research on the genetics of Alzheimer’s progresses, researchers are uncovering links between late-onset Alzheimer’s and a number of other genes. Several examples include:

- ABCA7. The exact role of ABCA7 isn’t clear, but the gene seems to be linked to a greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers suspect that it may have something to do with the gene’s role in how the body uses cholesterol.

- CLU. This gene helps regulate the clearance of amyloid-beta from the brain. Research supports the theory that an imbalance in the production and clearance of amyloid-beta is central to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

- CR1. A deficiency of the protein this gene produces may contribute to chronic inflammation in the brain. Inflammation is another possible factor in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

- PICALM. This gene is linked to the process by which brain nerve cells (neurons) communicate with each other. Smooth communication between neurons is important for proper neuron function and memory formation.

- PLD3. Scientists don’t know much about the role of PLD3 in the brain. But it’s recently been linked to a significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- TREM2. This gene is involved in the regulation of the brain’s response to inflammation. Rare variants in this gene are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- SORL1. Some variations of SORL1 on chromosome 11 appear to be associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers are continuing to learn more about the basic mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease, which may potentially lead to new ways to treat and prevent the disease.

As with APOE, these genes are risk factors, not direct causes. In other words, having a variation of one of these genes may increase your risk of Alzheimer’s. However, not everyone who has one will develop Alzheimer’s disease.

If several of your family members have developed dementia over the generations and particularly at a young age, you may want to seek genetic counseling for information and advice about your chances of developing Alzheimer’s disease when you’re older.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Down syndrome

Many people with Down syndrome develop Alzheimer’s disease. This is likely related to having three copies of chromosome 21 — and subsequently three copies of the gene for the protein that leads to the creation of beta-amyloid. Signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s tend to appear 10 to 20 years earlier in people with Down syndrome than they do for the general population.

Sex

There appears to be little difference in risk between men and women, but, overall, there are more women with the disease because they generally live longer than men.

Mild cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment is a decline in memory or other thinking skills that is greater than what would be expected for a person’s age, but the decline doesn’t prevent a person from functioning in social or work environments.

People who have mild cognitive impairment have a significant risk of developing dementia. When the primary mild cognitive impairment deficit is memory, the condition is more likely to progress to dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. A diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment enables the person to focus on healthy lifestyle changes, develop strategies to compensate for memory loss and schedule regular doctor appointments to monitor symptoms.

Past head trauma

People who’ve had a severe head trauma have a greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but much research is still needed in this area.

Poor sleep patterns

Research has shown that poor sleep patterns, such as difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Lifestyle and heart health

Research has shown that the same risk factors associated with heart disease may also increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. These include:

- Lack of exercise

- Obesity

- Smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Poorly controlled type 2 diabetes

These factors can all be modified. Therefore, changing lifestyle habits can to some degree alter your risk. For example, regular exercise and a healthy low-fat diet rich in fruits and vegetables are associated with a decreased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Studies have found an association between lifelong involvement in mentally and socially stimulating activities and a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Low education levels — less than a high school education — appear to be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

Aluminum

Aluminum is an element abundantly present in the earth. Aluminum occurs naturally in food and water and is widely used in products ranging from cans and cookware to medications and cosmetics. Some observational studies suggested a link between brain levels of aluminum and Alzheimer’s disease 5. Since the association was found, many studies have investigated whether aluminum increases the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. The findings are far from clear but to be safe, limiting excessive exposure may be a good idea.

Aluminum can come in many forms and its toxicity depends on the levels of trivalent aluminum (Al+3), which can react with water to produce aluminum superoxides, which in turn can deplete mitochondrial iron and promote generation of reactive oxygen species 6. Trivalent aluminum (Al+3)-induced formation of reactive oxygen species can lead to oxidative damage and apoptosis.

Drinking water

Several meta-analyses examined the association between aluminum levels in drinking water and dementia risk, and the evidence is mixed and inconclusive 7, 8, 9. The only high-quality study involved almost 4,000 older adults in southwest France, the Paquid study 10. It found that levels of aluminum consumption in drinking water in excess of 0.1 mg/day were associated with a doubling of dementia risk and a 3-fold increase in Alzheimer’s risk 11. For reference, the 2020 City of New York Drinking Water Quality Report states that the concentration of aluminum in NYC drinking water ranged from 0.008-0.040 mg/liter 12. Of the remaining 13 moderate quality studies, 6 found an association between higher aluminum levels in drinking water and increased dementia risk 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 4 found no associations 18, 19, 20 and 1 found a protective effect of higher soil levels of aluminum 21. Other elements present in drinking water, such as fluoride, copper, zinc, or iron, could also affect cognitive function and the results of these studies 22.

Antacids

Some antacids contain high levels of aluminum, as aluminum hydroxide reduces stomach acidity. Among medications, antacids and anti-ulceratives contain the highest levels of aluminum (35-208 mg/dose for antacids and 35-1450 mg/dose for anti-ulceratives) 23, though aluminum-free options exist (e.g., Rolaids, Tums). A very large meta-analysis of 9 observational studies including more than 6,000 people reported that regular antacid use was not associated with Alzheimer’s disease 24. Even when the analysis was confined to people who used antacids regularly for over 6 months, there was no association with Alzheimer’s. Studies with longer follow-up may be needed to definitively exclude the association between antacid use and dementia risk.

Antiperspirants

Aluminum salts in antiperspirants dissolve into the skin’s surface and form a temporary barrier within sweat ducts, which stops the flow of sweat to the skin’s surface. No studies have directly examined the link between aluminum-containing antiperspirant use and Alzheimer’s disease risk. However, a few studies have evaluated the link between antiperspirant use and breast cancer. Two studies found no increase in breast cancer risk 25, 26, but one other study reported that patients who used antiperspirant products more frequently and longer on shaved underarms were diagnosed with breast cancer at an earlier age 27. Studies show that aluminum salts in antiperspirants are poorly absorbed by the body, and the little that is absorbed is flushed out by the kidneys 28. However, if you regularly shave with a razor, aluminum may be more readily absorbed via small nicks and abrasions. To limit potential risks, avoid application of antiperspirants shortly after shaving and limit excessive use.

Occupational aluminum dust exposure

A meta-analysis of 3 observational studies including more than 1,000 people reported that occupational aluminum dust exposure was not associated with Alzheimer’s disease 29. However, further studies that precisely ascertain aluminum exposure are needed. In a more recent 2016 meta-analysis including 4 studies, the relationship between aluminum exposure and dementia was mixed due to the studies being too small 7.

There is no consistent or compelling evidence to associate aluminum with Alzheimer’s disease. Although a few studies have found associations between aluminum levels and Alzheimer’s risk, many others found no such associations. Due to the inconclusive nature of the findings, it may be advisable to limit excessive exposure.

Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by an accumulation of abnormal neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles 30.

Plaques are spherical microscopic lesions that have a core of extracellular amyloid beta-peptide surrounded by enlarged axonal endings. Beta-amyloid peptide is derived from a transmembrane protein known as an amyloid precursor protein (APP). The beta-amyloid peptide is cleaved from APP by the action of proteases named alpha, beta, and gamma-secretase. Usually, APP is cleaved by either alpha or beta-secretase and the tiny fragments formed by them are not toxic to neurons. However, sequential cleavage by beta and then gamma-secretase results in 42 amino acid peptides (beta-amyloid 42). Elevation in levels of beta-amyloid 42 leads to aggregation of amyloid that causes neuronal toxicity. Beta-amyloid 42 favors the formation of aggregated fibrillary amyloid protein over normal APP degradation. APP gene is located on chromosome 21, one of the regions linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Amyloid deposition occurs around meningeal and cerebral vessels and gray matter in Alzheimer’s disease. Gray matter deposits are multifocal and coalesce to form milliary structures called plaques. However, brain scans have noted amyloid plaques in some persons without dementia and then other persons had dementia but brain scans did not find any plaques.

Neurofibrillary tangles are fibrillary intracytoplasmic structures in neurons formed by a protein called tau. The primary function of the tau protein is to stabilize axonal microtubules. Microtubules run along neuronal axons and are essential for intracellular transport. Microtubule assembly is held together by tau protein. In Alzheimer’s disease, due to aggregation of extracellular beta-amyloid, there is hyperphosphorylation of tau which then causes the formation of tau aggregates. Tau aggregates form twisted paired helical filaments known as neurofibrillary tangles. They occur first in the hippocampus and then may be seen throughout the cerebral cortex. Tau-aggregates are deposited within the neurons. There is a staging system developed by Braak and Braak based on the topographical staging of neurofibrillary tangles into 6 stages, and this Braak staging is an integral part of the National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Tangles are more strongly correlated to Alzheimer’s than the plaques are.

Another feature of Alzheimer’s disease is granulovacuolar degeneration of hippocampal pyramidal cells by amyloid angiopathy. Some reports indicate that cognitive decline correlates more with a decrease in the density of presynaptic boutons from pyramidal neurons in laminae III and IV, rather than an increase in the number of plaques.

Neuronal loss in Nucleus Basalis of Myenert, leading to low acetylcholine has also been noted.

Vascular contribution to the neurodegenerative process of Alzheimer’s disease is not fully determined. The risk of dementia is increased fourfold with subcortical infarcts. The cerebrovascular disease also exaggerates the degree of dementia and its rate of progression 31.

Alzheimer’s disease prevention

Alzheimer’s disease is not a preventable condition. However, a number of lifestyle risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease can be modified. Evidence suggests that changes in diet, exercise and habits — steps to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease — may also lower your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders that cause dementia. Heart-healthy lifestyle choices that may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s include the following:

- Exercise regularly. Exercise may protect against brain aging and improve mental function. Avoid long periods of physical inactivity and engage in moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for at least 30 minutes, 3 to 5 days per week.

- Eat a diet of fresh produce, healthy oils and foods low in saturated fat. Studies have shown that a brain-healthy diet consists of high levels of fruits, vegetables, fish, and legumes. With a recent observational study reported that people who consumed large amounts of processed meat had an elevated risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease 32. There is also a growing evidence that specific diets— including the Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and MIND (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diets—may promote brain health. These healthy, balanced options include whole foods such as fish, nuts, and vegetables rich in vitamins, nutrients, and omega-3 fatty acids. The mechanisms by which a healthy diet influences cognitive functions are not yet clear, but may be mediated by dietary components with antioxidant (e.g., fruits, vegetables) and anti-inflammatory (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols) properties 33. A healthy diet also decreases the risks for type-2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol, all of which have been associated with cognitive decline and dementia. Additional research is needed to determine which combination of foods and nutrients are best for optimal brain health. But based on this study and previous ones, a heart-healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, and nuts, and low in full-fat dairy and red meat appear to be beneficial 34.

- Follow treatment guidelines to manage high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol. Some chronic diseases can raise the risk of dementia and some medications can impair your brain’s function. Periodically review your medications and supplements with your physician and work with them to manage your brain health. Once you have the right treatment plan, make sure to take your medications as directed and periodically check with your pharmacist.

- Protect your head. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is caused by a blow or jolt to the head – especially when the person is knocked out unconscious. Traumatic brain injuries can start a process in the brain where the substances that cause Alzheimer’s disease build up around the injured area. Wear a protective headgear in situations where there is a higher-than-normal risk of head injury – for example, riding a bike or scooter, working on a building site, horse-riding or playing football or cricket.

- If you smoke, ask your doctor for help to quit smoking. Smoking causes your arteries to become narrower, which can raise your blood pressure. It also increases your risk of cardiovascular disease, as well as several types of cancer.

- Keeping alcohol to a minimum. Drinking excessive amounts of alcohol increases your risk of stroke, heart disease and some cancers, as well as damaging your nervous system, including your brain.

- Maintaining a healthy weight. Being overweight or obese can increase your blood pressure and the risk of type 2 diabetes, both of which are linked to a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. If you are overweight or obese, even losing 5% to 10% of the excess weight can help reduce your risk of dementia.

- Get Enough Sleep. Impaired sleep contributes to cognitive decline and may increase your risk of Alzheimer’s disease. To protect your brain, establish a bedtime routine, maintain a regular sleep schedule, and treat sleep-disordered breathing such as apnea. Don’t eat or exercise within 2–3 hours of bedtime and avoid over-use of sleeping pills and inducing sleep with alcohol, particularly if you have restless legs syndrome.

- Alleviate Stress. Prolonged stress can harm your brain, leading to fatigue, disturbed sleep, poor concentration, and memory lapses. Protect yourself by making changes to your lifestyle and learning ways to cope.

- Treat Depression. The relationship between dementia and depression is complex. It appears that having untreated depression increases your risk of developing dementia. However, depression can happen as part of the overall symptoms of dementia itself.

- Treat hearing loss. Hearing loss may increase your risk of getting dementia. However the reasons for this are still unclear. To avoid hearing loss increasing your risk of getting dementia, it’s important to get your hearing tested. Speak to your doctor about being referred to an audiologist (a health care professional for hearing). This will show up any hearing issues and provide ways of managing them, such as using a hearing aid. Often, managing hearing loss works best when you start doing it early on. This means protecting your hearing from a young age. For example, you can avoid listening to loud noises for long periods, and wear ear protection when necessary.

- Be Social. Loneliness and depression can impair cognitive health, causing memory loss and attention deficits. Maintain and build your social connections. And if you experience depression, get support.

- Keep Learning. Stimulate your brain throughout life by engaging intellectually. Education at any age may protect against cognitive decline. Studies have shown that preserved thinking skills later in life and a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease are associated with participating in social events, reading, dancing, playing board games, creating art, playing an instrument, and other activities that require mental and social engagement.

Mediterranean diet is low in saturated fat and high in fiber 35:

- Fruits, vegetables, grains, beans, nuts, and seeds are eaten daily and make up the majority of food consumed.

- Fat, much of it from olive oil, may account for up to 40% of daily calories.

- Small portions of cheese or yogurt are usually eaten each day, along with a serving of fish, poultry, or eggs.

- Red meat is consumed now and then.

- Small amounts of red wine are typically taken with meals.

- Main meals consumed daily should be a combination of three elements: cereals, vegetables and fruits, and a small quantity of legumes, beans or other (though not in every meal). Cereals in the form of bread, pasta, rice, couscous or bulgur (cracked wheat) should be consumed as one–two servings per meal, preferably using whole or partly refined grains. Vegetable consumption should amount to two or more servings per day, in raw form for at least one of the two main meals (lunch and dinner). Fruit should be considered as the primary form of dessert, with one–two servings per meal. Consuming a variety of colors of both vegetables and fruit is strongly recommended to help ensure intake of a broad range of micronutrients and phytochemicals. The less these foods are cooked, the higher the retention of vitamins and the lower use of fuel, thus minimizing environmental impact.

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet 36:

- Grains and grain products: 7–8 servings per day, more than half of which are whole-grain foods

- Fruits: 4–5 servings per day

- Vegetables: 4–5 servings per day

- Low-fat or non-fat dairy foods: 2–3 servings per day

- Lean meats, fish, poultry: 6 or less servings or fewer per day

- Nuts, seeds, and legumes: 4–5 servings per week

- Added fats and oils: 2–3 servings per day

- Sweets: 5 or less servings per week

- Salt (sodium): 1,500 milligrams (mg) sodium lowers blood pressure even further than 2,300 mg sodium daily.

MIND diet is short for Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet 37. The MIND diet is similar to two other healthy meal plans: the DASH diet and the Mediterranean diet. Morris et al. 37 originally devised the MIND diet and found that the diet can slow cognitive decline over an average of 4.7 years in adults aged 58–98 years old. Interestingly, recent research found that the MIND diet and not the Mediterranean diet, protected against 12-year incidence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults 38. Also, a large observational study with older adults found that longer adherence to the MIND diet was associated with better verbal memory 39. The MIND diet promotes 10 healthy foods (Leafy greens, other veg, nuts, berries, fish, poultry, olive oil, beans, whole grains, red wine) and limits 5 other foods (red meat, butter, cheese, pastries and sweets, fried foods). While previous research shows that higher consumption of vegetables are associated with lower risk of cognitive decline 40, the strongest association was observed for higher intake of leafy greens 41. Previous research on cognitive function or dementia do not observe protective effects for overall fruit consumption 42. However, berries were shown to slow cognitive decline, particularly in global cognition and verbal memory in older adults 43.

- The MIND diet has 15 dietary components, including 10 “brain-healthy food groups” 44:

- Green leafy vegetables (like spinach and salad greens): At least six servings a week

- Other vegetables: At least one a day

- Nuts: Five servings a week

- Berries: Two or more servings a week

- Beans: At least three servings a week

- Whole grains: Three or more servings a day

- Fish: Once a week

- Poultry (like chicken or turkey): Two times a week

- Olive oil: Use it as your main cooking oil.

- Wine: One glass a day

- You AVOID:

- Red meat: Less than four servings a week

- Butter and margarine: Less than a tablespoon daily

- Cheese: Less than one serving a week

- Pastries and sweets: Less than five servings a week

- Fried or fast food: Less than one serving a week

- You AVOID:

The research found that high scores in all three diets were associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, but the MIND diet was the only diet in which even moderate adherence was beneficial. The MIND diet was also associated with a slower decline in global cognition, the equivalent of being 7.5 years younger in age cognitively. However, all of these studies are still observational, making it very difficult to confirm whether the benefits are caused by the diet or by other characteristics shared by the people who choose these foods. More research could help determine which of these diets has the most potential benefit for brain health. In the meantime, take note of the basic characteristics that they share: high levels of fruits, vegetables, fish, and legumes and low levels of processed foods, red meat, sweets, and sugars.

Dietary flavonols

Flavonols are a major class of the family of flavonoids, molecules that have interesting biological activity such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilatation effects, and they have been considered as potential anticancer agents 45. Flavonols are compounds found naturally in many fruits, vegetables, tea, and wine. A recent observational study reported that people with high intakes of flavonols had a significantly lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to people with low intakes 46. Findings come from a study of 921 elderly participants (average age of 81.2 years old) who were free of dementia at the time of enrollment. Every year, participants received clinical neurologic examinations while also being interviewed on the frequency and amounts of different food items and beverages they consumed. Participants were followed for up to 12 years (average of 6.1 years), during which 220 participants developed Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers found that participants who were in the top 20% in total flavonol intake had a 48% lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to those in the bottom 20%, after controlling for major lifestyle and other factors associated with dementia, such as age, education, genetic risk factor (ApoE), cognitive activity (e.g., reading, playing games, and writing letters), and physical activity (e.g., walking, biking, yard work) 46. Interestingly, the association between higher flavonol intake and reduced Alzheimer’s risk was stronger in men compared to women, such that men who were in the top 20% in total flavonol intake had a 76% lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s compared to men in the bottom 20%. The reasons for this sex difference are unknown 46.

Researchers further evaluated the different subclasses of flavonols, called kaempferol, myricetin, isorhamnetin, and quercetin.

- Kaempferol is abundant in kale, beans, tea, spinach, broccoli, capers, ginger, and dried goji berries 47. Participants who were in the top 20% in kaempferol intake had a 50% lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to those in the bottom 20%.

- Myricetin is rich in tea, wine, kale, oranges, nuts, berries, and tomatoes 47. Participants who were in the top 20% in myricetin intake had a 38% lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to those in the bottom 20%.

- Isorhamnetin is abundant in pears, olive oil, wine, and tomato sauce. Participants who were in the top 20% in isorhamnetin intake had a 38% lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to those in the bottom 20%.

- Quercetin is rich in tomatoes, capers, red onions, kale, berries, apples, and tea 47. Dietary intake of quercetin was not associated with a lower rate of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Because this study was an observational study and not a randomized clinical trial, it was not designed to prove that flavonols, or specific subclasses of flavonols like kaempferol, prevent Alzheimer’s disease. People who eat a diet rich in flavonols may be more likely to practice other healthy habits that are good for the brain. However, it is worth emphasizing that the associations between high flavonol intake and reduced Alzheimer’s disease risk remained significant even after controlling for some of these brain-healthy habits, such as cognitive and physical exercise.

Findings from this current study is consistent with previous ones reporting that greater flavonoid intake is associated with higher cognitive scores and slower cognitive decline 43, 48, 49, 50. Thus, a diet rich in fruits, dark-colored vegetables, and legumes appears to be beneficial for brain health and dementia prevention.

Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease

Many people with early onset Alzheimer’s disease are in their 40s and 50s. They have families, careers or are even caregivers themselves when Alzheimer’s disease strikes. In the United States, it is estimated that approximately 200,000 people have early onset.

Since health care providers generally don’t look for Alzheimer’s disease in younger people, getting an accurate diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s can be a long and frustrating process. Symptoms may be incorrectly attributed to stress or there may be conflicting diagnoses from different health care professionals. People who have early-onset Alzheimer’s may be in any stage of dementia — early stage, middle stage or late stage. The disease affects each person differently and symptoms will vary.

If you are experiencing memory problems:

- Have a comprehensive medical evaluation with a doctor who specializes in Alzheimer’s disease. Getting a diagnosis involves a medical exam and possibly cognitive tests, a neurological exam and/or brain imaging.

- Write down symptoms of memory loss or other cognitive difficulties to share with your health care professional.

- Keep in mind that there is no one test that confirms Alzheimer’s disease. A diagnosis is only made after a comprehensive medical evaluation.

What causes early onset Alzheimer’s disease?

Doctors do not understand why most cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease appear at such a young age. But in a few hundred families worldwide, scientists have pinpointed several rare genes that directly cause Alzheimer’s disease. People who inherit these rare genes tend to develop symptoms in their 30s, 40s and 50s. When Alzheimer’s disease is caused by deterministic genes, it is called “familial Alzheimer’s disease,” and many family members in multiple generations are affected.

Scientists have identified three genes in which mutations cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. If you inherit one of these mutated genes from either parent, you will probably have Alzheimer’s symptoms before age 65. The genes involved are:

- Amyloid precursor protein (APP)

- Presenilin 1 (PSEN1)

- Presenilin 2 (PSEN2)

Mutations of these genes cause the production of excessive amounts of a toxic protein fragment called amyloid-beta peptide. This peptide can build up in the brain to form clumps called amyloid plaques, which are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. A buildup of toxic amyloid-beta peptide and amyloid plaques may lead to the death of nerve cells and the progressive signs and symptoms of this disorder.

As amyloid plaques collect in the brain, tau proteins malfunction and stick together to form neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles are associated with the abnormal brain functions seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

However, some people who have early-onset Alzheimer’s don’t have mutations in these three genes. That suggests that some early-onset forms of Alzheimer’s disease are linked to other genetic mutations or other factors that haven’t been identified yet.

One of the active research trials is the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN), which studies individuals with dominant Alzheimer’s mutations (PSEN1, PSEN2 or APP). This research network includes observational studies and clinical trials.

Stages of Alzheimer’s disease

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease worsen over time, although the rate at which the disease progresses varies. On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives four to eight years after diagnosis, but can live as long as 20 years, depending on other factors.

Changes in the brain related to Alzheimer’s begin years before any signs of the disease. This time period, which can last for years, is referred to as preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

The stages below provide an overall idea of how abilities change once symptoms appear and should only be used as a general guide. (Dementia is a general term to describe the symptoms of mental decline that accompany Alzheimer’s and other brain diseases.)

Generally, the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are divided into 3 main stages: mild Alzheimer’s disease, moderate Alzheimer’s disease and severe Alzheimer’s disease. Be aware that it may be difficult to place a person with Alzheimer’s in a specific stage as stages may overlap.

Alzheimer’s disease typically progresses slowly in three general stages:

- Mild (early stage),

- Moderate (middle stage),

- Severe (late stage).

Since Alzheimer’s disease affects people in different ways, the timing and severity of dementia symptoms varies as each person progresses through the stages of Alzheimer’s disease differently.

Mild Alzheimer’s disease (early stage)

In the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease, a person may function independently. He or she may still drive, work and be part of social activities. Despite this, the person may feel as if he or she is having memory lapses, such as forgetting familiar words or the location of everyday objects.

Friends, family or others close to the individual begin to notice difficulties. During a detailed medical interview, doctors may be able to detect problems in memory or concentration. Common difficulties include:

- Problems coming up with the right word or name

- Trouble remembering names when introduced to new people

- Challenges performing tasks in social or work settings.

- Forgetting material that one has just read

- Losing or misplacing a valuable object

- Increasing trouble with planning or organizing

Moderate Alzheimer’s disease (middle stage)

Moderate Alzheimer’s disease is typically the longest stage and can last for many years. As the disease progresses, the person with Alzheimer’s will require a greater level of care.

During the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s, the dementia symptoms are more pronounced. A person may have greater difficulty performing tasks, such as paying bills, but they may still remember significant details about their life.

You may notice the person with Alzheimer’s confusing words, getting frustrated or angry, or acting in unexpected ways, such as refusing to bathe. Damage to nerve cells in the brain can make it difficult to express thoughts and perform routine tasks.

At this point, symptoms will be noticeable to others and may include:

- Forgetfulness of events or about one’s own personal history

- Feeling moody or withdrawn, especially in socially or mentally challenging situations

- Being unable to recall their own address or telephone number or the high school or college from which they graduated

- Confusion about where they are or what day it is

- The need for help choosing proper clothing for the season or the occasion

- Trouble controlling bladder and bowels in some individuals

- Changes in sleep patterns, such as sleeping during the day and becoming restless at night

- An increased risk of wandering and becoming lost

- Personality and behavioral changes, including suspiciousness and delusions or compulsive, repetitive behavior like hand-wringing or tissue shredding

Severe Alzheimer’s disease (late stage)

In the final stage of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia symptoms are severe. Individuals lose the ability to respond to their environment, to carry on a conversation and, eventually, to control movement. They may still say words or phrases, but communicating pain becomes difficult. As memory and cognitive skills continue to worsen, significant personality changes may take place and individuals need extensive help with daily activities.

At this stage, individuals may:

- Need round-the-clock assistance with daily activities and personal care

- Lose awareness of recent experiences as well as of their surroundings

- Experience changes in physical abilities, including the ability to walk, sit and, eventually, swallow

- Have increasing difficulty communicating

- Become vulnerable to infections, especially pneumonia

Alzheimer’s disease symptoms

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive condition, which means the symptoms develop gradually over many years and eventually become more severe. It affects multiple brain functions.

Brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease lead to growing trouble with:

- Memory loss

- Thinking and reasoning problem

- Making judgments and decisions problem

- Planning and performing familiar tasks problem

- Changes in personality and behavior

The first sign of Alzheimer’s disease is usually minor memory loss. An early sign of Alzheimer’s disease is usually difficulty remembering recent events or conversations and forgetting the names of places and objects (short-term memory loss). As the disease progresses, memory impairments worsen and other symptoms develop, such as:

- confusion, disorientation and getting lost in familiar places

- difficulty planning or making decisions

- problems with speech and language

- problems moving around without assistance or performing self-care tasks

- personality changes, such as becoming aggressive, demanding and suspicious of others

- hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that are not there) and delusions (believing things that are untrue)

- low mood or anxiety.

At first, a person with Alzheimer’s disease may be aware of having difficulty with remembering things and organizing thoughts. A family member or friend may be more likely to notice how the symptoms worsen.

The rate at which the symptoms progress is different for each individual. And sometimes these symptoms are confused with other conditions and may initially be put down to old age.

In some cases, other conditions can be responsible for symptoms getting worse. These conditions include:

- infections

- stroke

- delirium

As well as these conditions, other things, such as certain medicines, can also worsen the symptoms of dementia.

Anyone with Alzheimer’s disease whose symptoms are rapidly getting worse should be seen by a doctor so these can be managed.

Early symptoms

In the early stages, the main symptom of Alzheimer’s disease is memory lapses.

For example, someone with early Alzheimer’s disease may:

- forget about recent conversations or events

- misplace items

- forget the names of places and objects

- have trouble thinking of the right word

- ask questions repetitively

- show poor judgement or find it harder to make decisions

- become less flexible and more hesitant to try new things

There are often signs of mood changes, such as increasing anxiety or agitation, or periods of confusion.

Middle-stage symptoms

As Alzheimer’s disease develops, memory problems will get worse. Someone with Alzheimer’s disease may find it increasingly difficult to remember the names of people they know and may struggle to recognize their family and friends.

Other symptoms may also develop, such as:

- increasing confusion and disorientation – for example, getting lost, or wandering and not knowing what time of day it is

- obsessive, repetitive or impulsive behavior

- delusions (believing things that are untrue) or feeling paranoid and suspicious about carers or family members

- problems with speech or language (aphasia)

- disturbed sleep

- changes in mood, such as frequent mood swings, depression and feeling increasingly anxious, frustrated or agitated

- difficulty performing spatial tasks, such as judging distances

- seeing or hearing things that other people do not (hallucinations)

Some people also have some symptoms of vascular dementia.

By this stage, someone with Alzheimer’s disease usually needs support to help them with everyday living. For example, they may need help eating, washing, getting dressed and using the toilet.

Later symptoms

In the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease, the symptoms become increasingly severe and can be distressing for the person with the condition, as well as their carers, friends and family.

Hallucinations and delusions may come and go over the course of the disease, but can get worse as the condition progresses.

Sometimes people with Alzheimer’s disease can be violent, demanding and suspicious of those around them.

A number of other symptoms may also develop as Alzheimer’s disease progresses, such as:

- difficulty eating and swallowing (dysphagia)

- difficulty changing position or moving around without assistance

- weight loss – sometimes severe

- unintentional passing of urine (urinary incontinence) or stools (bowel incontinence)

- gradual loss of speech

- significant problems with short- and long-term memory

In the severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease, people may need full-time care and assistance with eating, moving and personal care.

Memory loss

Everyone has occasional memory lapses. It’s normal to lose track of where you put your keys or forget the name of an acquaintance. But the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease persists and worsens, affecting the ability to function at work or at home.

People with Alzheimer’s disease may:

- Repeat statements and questions over and over

- Forget conversations, appointments or events, and not remember them later

- Routinely misplace possessions, often putting them in illogical locations

- Get lost in familiar places

- Eventually forget the names of family members and everyday objects

- Have trouble finding the right words to identify objects, express thoughts or take part in conversations

According to the National Institute on Aging, in addition to memory problems, someone with Alzheimer’s disease may experience one or more of the following signs:

- Memory loss that disrupts daily life, such as getting lost in a familiar place or repeating questions.

- Trouble handling money and paying bills.

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work or at leisure.

- Decreased or poor judgment.

- Misplaces things and being unable to retrace steps to find them.

- Changes in mood, personality, or behavioral.

If you or someone you know has several or even most of the signs listed above, it does not mean that you or they have Alzheimer’s disease. It is important to consult a health care provider when you or someone you know has concerns about memory loss, thinking skills, or behavioral changes.

- Some causes for symptoms, such as depression and drug interactions, are reversible. However, they can be serious and should be identified and treated by a health care provider as soon as possible.

- Early and accurate diagnosis provides opportunities for you and your family to consider or review financial planning, develop advance directives, enroll in clinical trials, and anticipate care needs.

Thinking and reasoning problem

Alzheimer’s disease causes difficulty concentrating and thinking, especially about abstract concepts such as numbers.

Multitasking is especially difficult, and it may be challenging to manage finances, balance checkbooks and pay bills on time. These difficulties may progress to an inability to recognize and deal with numbers.

Making judgments and decisions problem

The ability to make reasonable decisions and judgments in everyday situations will decline. For example, a person may make poor or uncharacteristic choices in social interactions or wear clothes that are inappropriate for the weather. It may be more difficult to respond effectively to everyday problems, such as food burning on the stove or unexpected driving situations.

Planning and performing familiar tasks problem

Once-routine activities that require sequential steps, such as planning and cooking a meal or playing a favorite game, become a struggle as the disease progresses. Eventually, people with advanced Alzheimer’s may forget how to perform basic tasks such as dressing and bathing.

Changes in personality and behavior

Brain changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease can affect moods and behaviors. Problems may include the following:

- Depression

- Apathy

- Social withdrawal

- Mood swings

- Distrust in others

- Irritability and aggressiveness

- Changes in sleeping habits

- Wandering

- Loss of inhibitions

- Delusions, such as believing something has been stolen

Preserved skills

Many important skills are preserved for longer periods even while symptoms worsen. Preserved skills may include reading or listening to books, telling stories and reminiscing, singing, listening to music, dancing, drawing, or doing crafts.

These skills may be preserved longer because they are controlled by parts of the brain affected later in the course of the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease complications

Memory and language loss, impaired judgment, and other cognitive changes caused by Alzheimer’s can complicate treatment for other health conditions. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may not be able to:

- Communicate that he or she is experiencing pain — for example, from a dental problem

- Report symptoms of another illness

- Follow a prescribed treatment plan

- Notice or describe medication side effects

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses to its last stages, brain changes begin to affect physical functions, such as swallowing, balance, and bowel and bladder control. These effects can increase vulnerability to additional health problems such as:

- Inhaling food or liquid into the lungs (aspiration)

- Pneumonia and other infections

- Falls

- Fractures

- Bedsores

- Malnutrition or dehydration

Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis

There is no single diagnostic test that can determine if a person has Alzheimer’s disease. Physicians (often with the help of specialists such as neurologists, neuropsychologists, geriatricians and geriatric psychiatrists) use a variety of approaches and tools to help make a diagnosis. Although physicians can almost always determine if a person has dementia, it may be difficult to identify the exact cause.

Memory problems are not just caused by dementia, they can also be caused by:

- depression or anxiety

- stress

- medicines

- alcohol or drugs

- sleeping problems (insomnia)

- other health problems – such as hormonal disturbances or nutritional deficiencies

Medical history

During the medical workup, your health care provider will review your medical history, including psychiatric history and history of cognitive and behavioral changes. He or she will want to know about any current and past illnesses, as well as any medications you are taking. The doctor will also ask about key medical conditions affecting other family members, including whether they may have had Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias.

Physical exam and diagnostic tests

During a medical workup, you can expect the physician to:

- Ask about diet, nutrition and use of alcohol.

- Review all medications. (Bring a list or the containers of all medicines currently being taken, including over-the-counter drugs and supplements.)

- Check blood pressure, temperature and pulse.

- Listen to the heart and lungs.

- Perform other procedures to assess overall health.

- Collect blood or urine samples for laboratory testing. Blood tests may help your doctor rule out other potential causes of memory loss and confusion, such as a thyroid disorder or vitamin deficiencies.

Neurological exam

During a neurological exam, the physician will closely evaluate the person for problems that may signal brain disorders other than Alzheimer’s. The doctor will look for signs of small or large strokes, Parkinson’s disease, brain tumors, fluid accumulation on the brain, and other illnesses that may impair memory or thinking.

Your doctor will perform a physical exam and likely assess overall neurological health by testing the following:

- Reflexes

- Muscle tone and strength

- Ability to get up from a chair and walk across the room

- Sense of sight and hearing

- Coordination

- Balance

Information from a physical exam and laboratory tests can help identify health issues that can cause symptoms of dementia. Common causes of dementia-like symptoms are depression, untreated sleep apnea, delirium, side effects of medications, thyroid problems, certain vitamin deficiencies and excessive alcohol consumption. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, these conditions often may be reversed with treatment.

Mental status and neuropsychological testing

Your doctor may conduct a brief mental status test or a more extensive set of tests to assess memory and other thinking skills. Longer forms of neuropsychological testing may provide additional details about mental function compared with people of a similar age and education level. These tests are also important for establishing a starting point to track the progression of symptoms in the future.

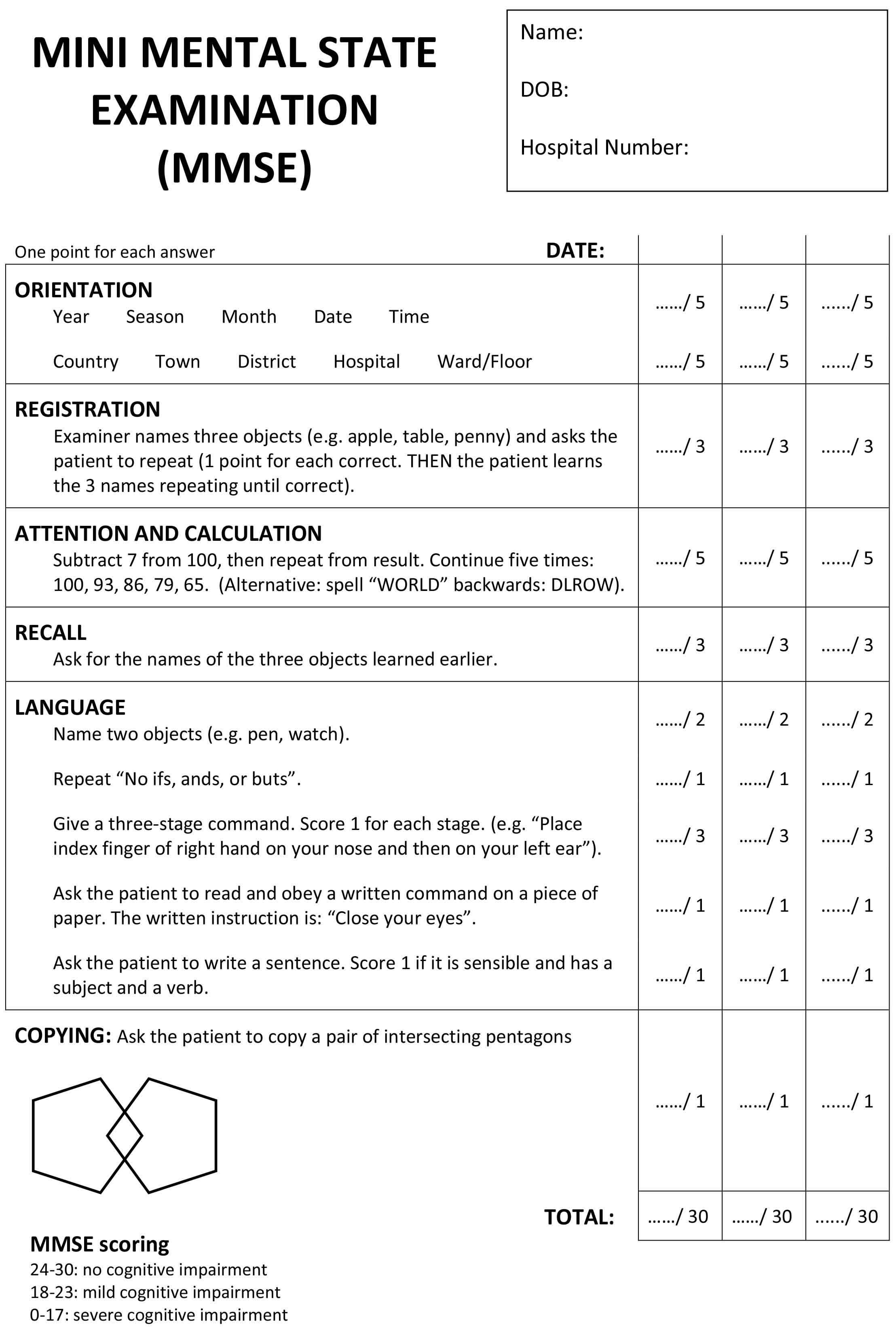

Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and the Mini-Cog test

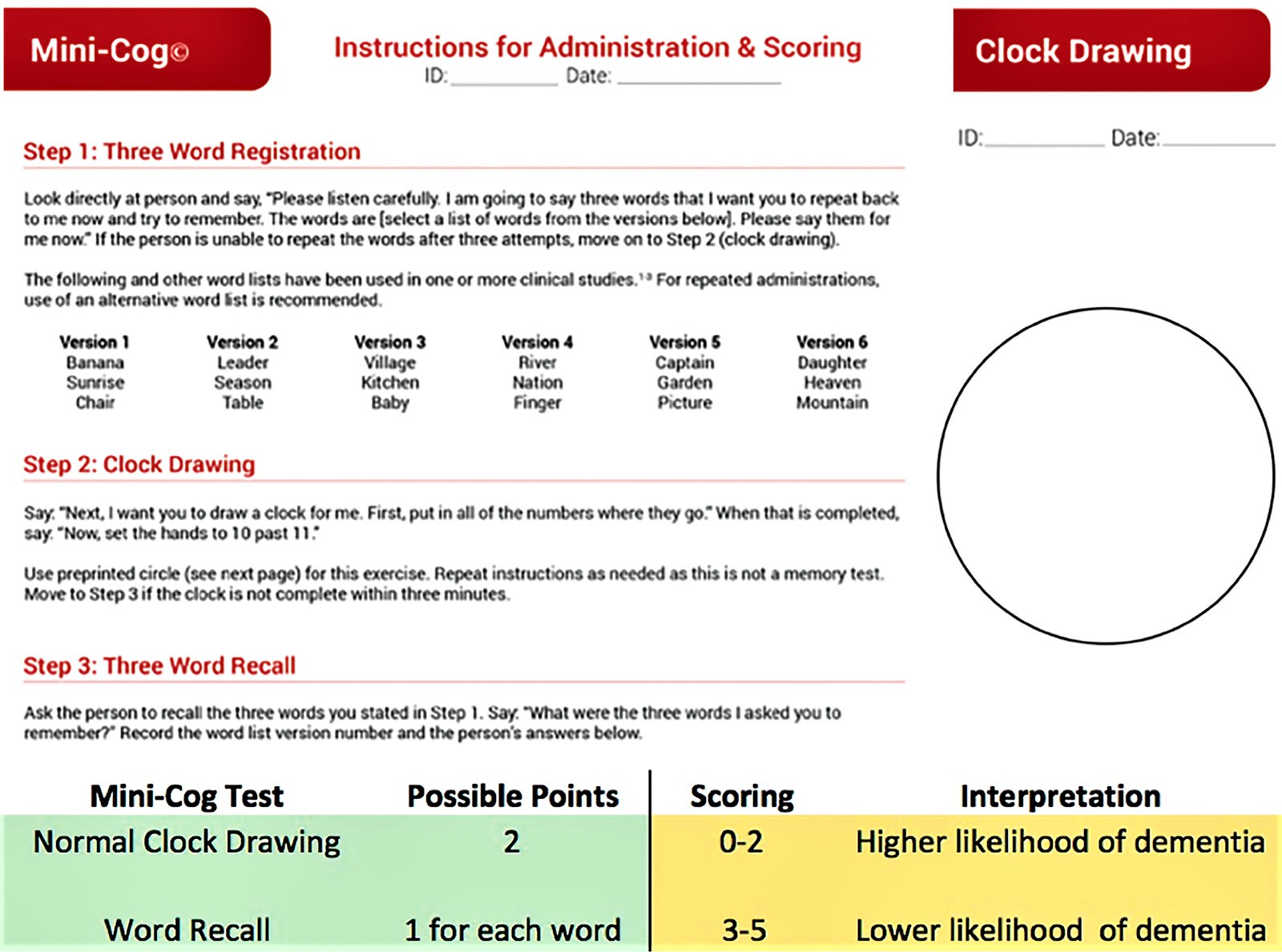

The Mini-Mental State Exam and Mini-Cog test are two commonly used assessments.

During the Mini-Mental State Exam, a health professional asks a patient a series of questions designed to test a range of everyday mental skills. The maximum MMSE score is 30 points. A score of 20 to 24 suggests mild dementia, 13 to 20 suggests moderate dementia, and less than 12 indicates severe dementia. On average, the MMSE score of a person with Alzheimer’s declines about two to four points each year.

During the Mini-Cog, a person is asked to complete two tasks:

- Remember and a few minutes later repeat the names of three common objects.

- Draw a face of a clock showing all 12 numbers in the right places and a time specified by the examiner.

The results of this brief test can help a physician determine if further evaluation is needed.

Figure 1. Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)

Figure 2. Mini-Cog test

Brain imaging

Images of the brain are now used chiefly to pinpoint visible abnormalities related to conditions other than Alzheimer’s disease — such as strokes, trauma or tumors — that may cause cognitive change. New imaging applications — currently used primarily in major medical centers or in clinical trials — may enable doctors to detect specific brain changes caused by Alzheimer’s disease.

Imaging of brain structures include the following:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI uses radio waves and a strong magnetic field to produce detailed images of the brain. MRI scans are used primarily to rule out other conditions. While they may show brain shrinkage, the information doesn’t currently add significant value to making a diagnosis.

- Computerized tomography (CT). A CT scan, a specialized X-ray technology, produces cross-sectional images (slices) of your brain. It’s currently used chiefly to rule out tumors, strokes and head injuries.

Imaging of disease processes can be performed with positron emission tomography (PET). During a PET scan, a low-level radioactive tracer is injected into the blood to reveal a particular feature in the brain. PET imaging may include the following:

- Fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans show areas of the brain in which nutrients are poorly metabolized. Identifying patterns of degeneration — areas of low metabolism — can help distinguish between Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia.

- Amyloid PET imaging can measure the burden of amyloid deposits in the brain. This imaging is primarily used in research but may be used if a person has unusual or very early onset of dementia symptoms.

- Tau Pet imaging, which measures the burden of neurofibrillary tangles in the brain, is only used in research.

In special circumstances, such as rapidly progressive dementia or very early onset dementia, other tests may be used to measure abnormal beta-amyloid or tau in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Future diagnostic tests

Researchers are working on tests that can measure the biological evidence of disease processes in the brain. These tests may improve the accuracy of diagnoses and enable earlier diagnosis before the onset of symptoms.

Genetic testing generally isn’t recommended for a routine Alzheimer’s disease evaluation. The exception is people who have a family history of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Meeting with a genetic counselor to discuss the risks and benefits of genetic testing is recommended before undergoing any tests.

Genetic testing

Most experts don’t recommend genetic testing for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. In some instances of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, however, genetic testing may be appropriate.

Most clinicians discourage testing for the APOE genotype because the results are difficult to interpret. And doctors can generally diagnose Alzheimer’s disease without the use of genetic testing.

Testing for the mutant genes that have been linked to early-onset Alzheimer’s — APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 — may provide more-certain results if you’re showing early symptoms or if you have a family history of early-onset disease. Genetic testing for early-onset Alzheimer’s disease may also have implications for current and future therapeutic drug trials as well as for family planning. Before being tested, it’s important to weigh the emotional consequences of having that information. The results may affect your eligibility for certain forms of insurance, such as disability, long-term care and life insurance.

Researchers are also studying genes that may protect against Alzheimer’s disease. One variant of the APOE gene, called APOE Christchurch, appears to be protective, with an effect similar to that of APOE e2. More research is needed to understand this variant’s effect on Alzheimer’s disease risk.

Alzheimer’s disease treatment

There is currently no known cure for Alzheimer’s disease.

Treatment addresses several different areas:

- Helping people maintain mental function.

- Managing behavioral symptoms.

- Slowing or delaying the symptoms of the disease.

Medications

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved medications that fall into two categories:

- Drugs that may delay clinical decline in people living with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Drugs that may temporarily mitigate some symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

When considering any treatment, it is important to have a conversation with your health care professional to determine whether it is appropriate. A physician who is experienced in using these types of medications should monitor people who are taking them and ensure that the recommended guidelines are strictly observed.

Alzheimer’s disease treatments overview:

- May delay clinical decline

- Aducanumab (Aduhelm™) approved for Alzheimer’s disease. Side effects include Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA) which is swelling in areas of the brain, with or without small spots of bleeding in or on the surface of the brain; headache and fall.

- Treats cognitive symptoms (memory and thinking)

- Donepezil (Aricept®) approved for mild to severe dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, muscle cramps and increased frequency of bowel movements.

- Galantamine (Razadyne®) approved for mild to moderate dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and increased frequency of bowel movements.

- Rivastigmine (Exelon®) approved for mild to moderate dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and increased frequency of bowel movements.

- Memantine (Namenda®) approved for moderate to severe dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Side effects include headache, constipation, confusion and dizziness.

- Memantine + Donepezil (Namzaric®) approved for moderate to severe dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, increased frequency of bowel movements, headache, constipation, confusion and dizziness.

- Treats non-cognitive symptoms (behavioral and psychological)

- Suvorexant (Belsomra®) approved for insomnia in people living with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Side effects include impaired alertness and motor coordination, worsening of depression or suicidal thinking, complex sleep behaviors, sleep paralysis, compromised respiratory function.

Table 1. Alzheimer’s disease treatments summary

| Drug Name | Drug Type and Use | Delivery Method | How It Works | Manufacturer’s Recommended Dosage | Common Side Effects | Prescribing information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aducanumab (Aduhelm®) | Disease-modifying immunotherapy prescribed to treat mild cognitive impairment or mild Alzheimer’s | Intravenous (IV): Dose is determined by a person’s weight; given over one hour every four weeks; most people will start with a lower dose and over a period of time increase the amount of medicine to reach the full prescription dose | Removes abnormal beta-amyloid to help reduce the number of plaques in the brain |

| Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which can lead to fluid buildup or bleeding in the brain; also headache, dizziness, falls, diarrhea, confusion | https://www.biogencdn.com/us/aduhelm-pi.pdf |

| Donepezil (Aricept®) | Cholinesterase inhibitor prescribed to treat symptoms of mild, moderate, and severe Alzheimer’s | Tablet: Once a day; dosage may be increased over time if well tolerated Orally disintegrating tablet: Same dosing regimen as above | Prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine in the brain |

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, fatigue, weight loss | http://www.aricept.com |

| Rivastigmine (Exelon®) | Cholinesterase inhibitor prescribed to treat symptoms of mild, moderate, and severe Alzheimer’s | Capsule: Twice a day; dosage may be increased over time, at minimum two-week intervals, if well tolerated Patch: Once a day; dosage amount may be increased over time, at minimum four-week intervals, if well tolerated | Prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine and butyrylcholine (a brain chemical similar to acetylcholine) in the brain |

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, indigestion, muscle weakness | https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022083s008lbl.pdf |

| Memantine (Namenda®) | N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist prescribed to treat symptoms of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s | Tablet: Once a day; dosage may be increased in amount and frequency (up to twice a day) if well tolerated Oral solution: Same dosage as tablet Extended-release capsule: Once a day; dosage may increase in amount over time, at minimum one-week intervals, if well tolerated | Blocks the toxic effects associated with excess glutamate and regulates glutamate activation |

| Dizziness, headache, diarrhea, constipation, confusion | https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021487s010s012s014,021627s008lbl.pdf |

| Manufactured combination of memantine and donepezil (Namzaric®) | NMDA antagonist and cholinesterase inhibitor prescribed to treat symptoms of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s | Extended-release capsule: Once a day; initial dosage depends on whether the person is already on a stable dose of memantine and/or donepezil; dosage may increase over time, at minimum one-week intervals, if well tolerated | Blocks the toxic effects associated with excess glutamate and prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine in the brain |

| Headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, anorexia | https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/namzaric_pi.pdf |

| Galantamine (Razadyne®) | Cholinesterase inhibitor prescribed to treat symptoms of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s | Tablet: Twice a day; dosing may increase over time, at minimum four-week intervals, if well tolerated Extended-release capsule: Same dosage as tablet but taken once a day | Prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine and stimulates nicotinic receptors to release more acetylcholine in the brain |

| Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, dizziness, headache | https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021615s021lbl.pdf |

Footnote: * Available as a generic drug.

[Source: National Institutes of Health. National Institute on Aging 51 ]Drugs that may delay clinical decline

Drugs in this category may delay clinical decline with benefits to both cognition and function in people living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Aducanumab also known as aducanumab-avwa that is marketed as Aduhelm, is a human monoclonal antibody intravenous (IV) infusion therapy that is specific for beta-amyloid for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease 52. Aducanumab (Aduhelm) is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2021 under the accelerated approval pathway, which provides patients with a serious disease earlier access to drugs when there is an expectation of clinical benefit despite some uncertainty about the clinical benefit 53. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in confirmatory trial(s). Aducanumab (Aduhelm) works by targeting beta-amyloid, a microscopic protein fragment that forms in the brain and accumulates into plaques. These plaques disrupt communication between nerve cells in the brain and may also activate immune system cells that trigger inflammation and devour disabled nerve cells. While scientists aren’t sure what causes cell death and tissue loss during the course of Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid plaques are one of the potential contributors. Aducanumab (Aduhelm) is the first therapy to demonstrate that removing beta-amyloid resulted in better clinical outcomes 54.

- Aduhelm was shown in clinical trials to delay the clinical decline of people living with early Alzheimer’s disease (mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer’s or mild Alzheimer’s dementia).