Anal fissure

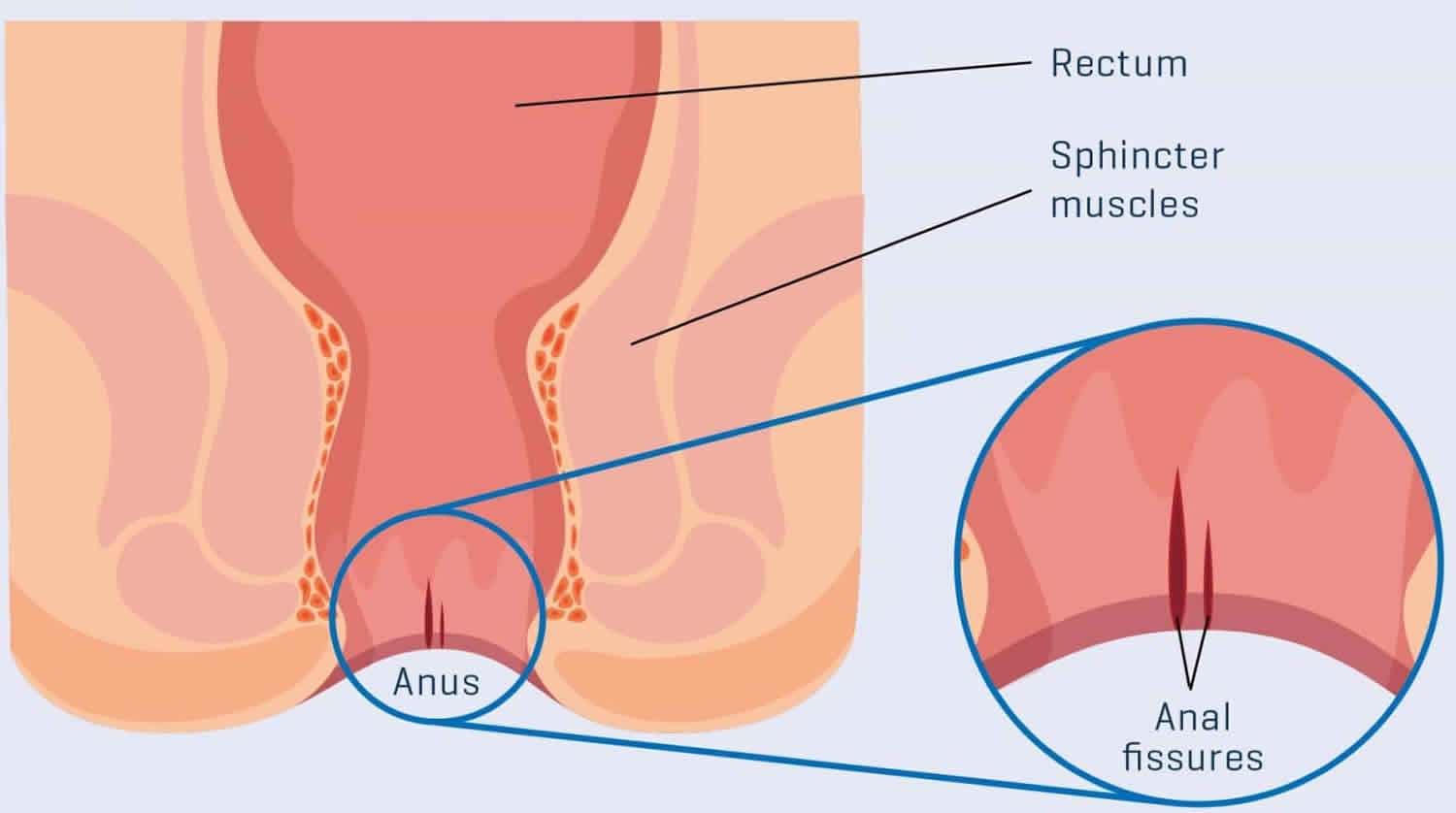

Anal fissure also known as fissure-in-ano, is a linear or oval shaped tear in the thin, moist tissue (mucosa) that lines the anal canal starting just below the dentate line extending to the anal verge (see Figures 1 and 2 below) 1. An anal fissure is a superficial tear in the skin distal to the dentate line that may occur when you pass hard or large stools during a bowel movement 2. About 235,000 new cases of anal fissure are reported every year in the US and about 40% of them persist for months and even years 3. Anal fissures are common in those with a history of constipation or hard stools, low fiber diet, trauma, diarrhea, previous anal surgery or as a consequence of previous bariatric procedure in obese people 2, 4, 5, 6)). Anal fissures typically cause pain and bleeding with bowel movements. You also may experience spasms in the ring of muscle at the end of your anus (anal sphincter). The anal sphincter is the ring of muscles that open and close the anus. Sometimes people confuse anal fissures with hemorrhoids (also called piles), which are swollen veins (similar to varicose veins) in your rectum or anus. Hemorrhoids can develop inside the rectum (internal hemorrhoids) or under the skin around the anus (external hemorrhoids).

The classification of anal fissures is based on causative factors 7:

- Primary anal fissures are typically benign and are likely to be related to local trauma such as hard stools, prolonged diarrhea, vaginal delivery, repetitive injury or penetration.

- Secondary anal fissures are found in patients with previous anal surgical procedures, inflammatory bowel disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease), granulomatous diseases (e.g. tuberculosis, sarcoidosis), infections (e.g. HIV/AIDS, syphilis) or malignancy 5.

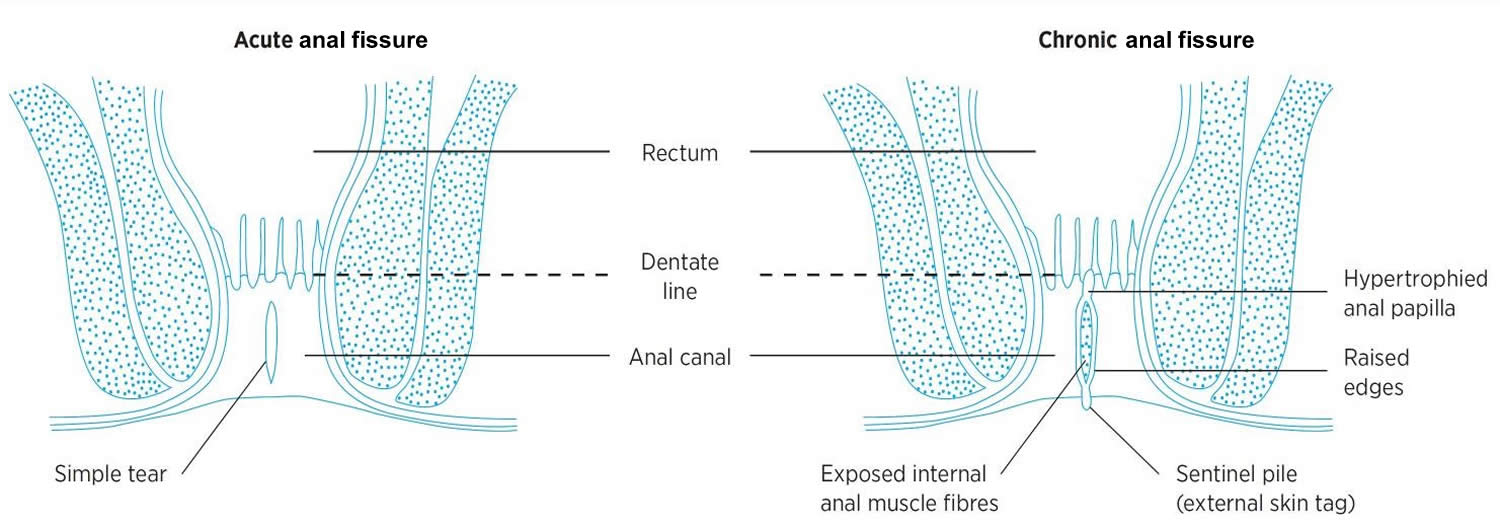

Anal fissures can be acute (lasting less than six weeks) or chronic (more than six weeks) 2. Approximately 40% of patients who present with acute anal fissures progress to chronic anal fissures 8. The majority of anal fissures occur at either the posterior or anterior midline. Other locations warrant further workup to rule out secondary causes (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, among others).

The diagnosis of an anal fissure is primarily clinical. Your doctor will likely ask about your medical history including your toilet habits and perform a physical exam, including a gentle inspection of the anal region. Often the tear is visible by gently parting your buttocks. Usually this exam is all that’s needed to diagnose an anal fissure.

An acute anal fissure commonly heals with 4–8 weeks of conservative therapy. Most anal fissures heal within a few weeks if you take steps to keep your stool soft, such as increasing your intake of fiber (adults should aim to eat at least 30g of fiber a day) and fluids 9. Soaking in warm water or sitz baths for 10 to 20 minutes several times a day, especially after bowel movements, can help relax the anal sphincter and promote healing. If this therapy fails, other treatments may involve prescription creams such as nitrates or calcium channel blockers. You may even need Botox injections into the muscle in the anus (called the anal sphincter). If the anal fissure becomes chronic, minor surgery is usually required to relax the anal muscle can be used as a last resort 10.

Figure 1. Anus anatomy

Figure 2. Anal fissure

See your doctor if you have pain during bowel movements or notice blood on stools or toilet paper after a bowel movement.

See your doctor if you think you have an anal fissure. Do not let embarrassment stop you seeking help. Anal fissures are a common problem doctors are used to dealing with.

Most anal fissures get better without treatment, but your doctor will want to rule out other conditions with similar symptoms, such as piles (hemorrhoids).

Your doctor can also tell you about self-help measures and treatments that can relieve your symptoms and reduce the risk of fissures coming back.

Do anal fissures heal?

Yes. An acute anal fissure (lasting less than six weeks) commonly heals with 4–8 weeks of conservative therapy. If this therapy fails and the fissure becomes chronic, surgery is usually required 11.

Can anal fissure lead to colon cancer?

Anal fissures do not increase the risk of colon cancer nor cause it. However, more serious conditions can cause similar symptoms. Even when an anal fissure has healed completely, your doctor may request other tests. A colonoscopy may be done to rule out other causes of rectal bleeding.

Can anal fissures be prevented or avoided?

Keeping bowel movements regular and avoiding constipation can help reduce your chances of an anal fissure. Add more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains to your diet to get enough fiber. Drink plenty of fluids and get some exercise in every day to help keep your digestive system moving.

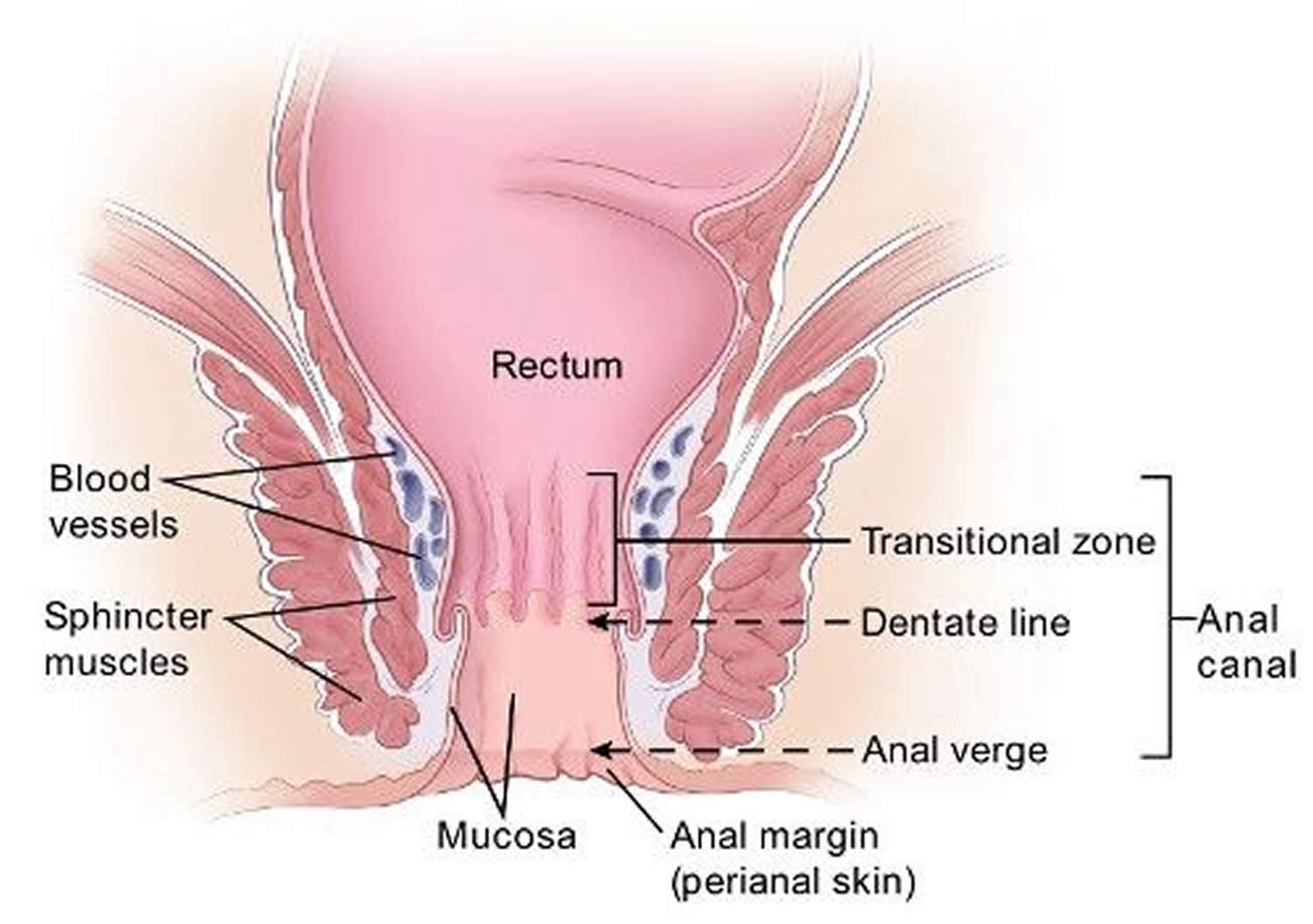

The anus

The anus is connected to the rectum by the anal canal. The anus is the continuation of the large intestine (the colon or large bowel) inferior to the rectum. It’s where the end of the intestines connect to the outside of the body.

The anal canal is about 1-1/2 inches (about 3 to 5 cm) long, it begins where the rectum passes through the levator ani (the muscle that forms the pelvic floor) and goes to the anal verge. The anal verge is where the anal canal connects to the outside skin at the anus. This skin around the anal verge is called the perianal skin (previously called the anal margin). The anal canal has two ring-shaped muscles (called sphincter muscles – an internal and external anal sphincter) that keep the anus closed and prevent stool from leaking out.

As food is digested, it passes from the stomach to the small intestine. It then moves from the small intestine into the main part of the large intestine (called the colon). The colon absorbs water and salt from the digested food. The waste matter that’s left after going through the colon is known as feces or stool. Stool is stored in the last part of the large intestine, called the rectum. From there, stool is passed out of the body through the anus as a bowel movement.

The inner lining of the anal canal is the mucosa. Glands and ducts (tubes leading from the glands) are found under the mucosa. The glands make mucus, which acts as a lubricating fluid.

The anal canal changes as it goes from the rectum to the anal verge. The parts of the anus include the:

- Cells above the anal canal (in the rectum) and in the part of the anal canal close to the rectum are shaped like tiny columns.

- Most cells near the middle of the anal canal are shaped like cubes and are called transitional cells. This area is called the transitional zone – this is where the rectum meets the anal canal.

- About midway down the anal canal is the dentate line, which is where most of the anal glands empty into the anus.

- Below the dentate line are flat (squamous) cells.

- At the anal verge, the squamous cells of the lower anal canal merge with the skin just outside the anus. This skin around the anal verge called the perianal skin or the anal margin, is also made up of squamous cells, but it also contains sweat glands and hair follicles, which are not found in the lining of the lower anal canal. The anal margin is the lower part of the anal canal and it contains muscles called the anal sphincters. You have an internal and external anal sphincter. They are the muscles that control your bowel movements.

Figure 3. Rectum and anus

Anal fissure signs and symptoms

The most common symptom of an anal fissure is a shooting pain in the anus and surrounding area. Anal fissures often cause painful bowel movements and bleeding. You may also see blood on the toilet paper after wiping. Anal fissures may also cause itching in the anal area.

Signs and symptoms of an anal fissure may include:

- Pain, sometimes severe, during bowel movements

- Sharp pain often followed by a deep burning pain after bowel movements that can last up to several hours

- Bright red blood on the stool or toilet paper after a bowel movement

- A visible crack in the skin around the anus

- A small lump or skin tag on the skin near the anal fissure.

Anal fissure complications

Complications of anal fissure can include:

- Failure to heal. An anal fissure that fails to heal within eight weeks is considered chronic and may need further treatment.

- Recurrence. Once you’ve experienced an anal fissure, you are prone to having another one.

- A tear that extends to surrounding muscles. An anal fissure may extend into the ring of muscle that holds your anus closed (internal anal sphincter), making it more difficult for your anal fissure to heal. An unhealed fissure can trigger a cycle of discomfort that may require medications or surgery to reduce the pain and to repair or remove the fissure.

- Bleeding

- Pain

- Infection

- Incontinence

- Fistula formation – the most serious complication

Anal fissure causes

The exact cause of anal fissure is unknown but trauma caused by (especially hard) fecal mass and hypertonicity of the internal sphincter are thought to be the initiating factors 7. Anal fissures are usually a result of straining during a bowel movement, causing injury to the anal canal. Anal fissures also can be caused by repeated diarrhea, when blood flow to the area is decreased (in older adults), after childbirth, or in people with Crohn’s disease.

Common causes of anal fissure include:

- Passing large or hard stools

- Constipation and straining during bowel movements

- Chronic diarrhea

- Anal intercourse

- Pregnancy and childbirth

Less common causes of anal fissures include:

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

- Anal cancer

- HIV

- Tuberculosis

- Syphilis

- Herpes

Risk factors for developing anal fissure

Factors that may increase your risk of developing an anal fissure include:

- Constipation. Straining during bowel movements and passing hard stools increase the risk of tearing.

- Childbirth. Anal fissures are more common in women after they give birth.

- Crohn’s disease. This inflammatory bowel disease causes chronic inflammation of the intestinal tract, which may make the lining of the anal canal more vulnerable to tearing.

- Anal intercourse.

- Age. Anal fissures can occur at any age, but are more common in infants and middle-aged adults.

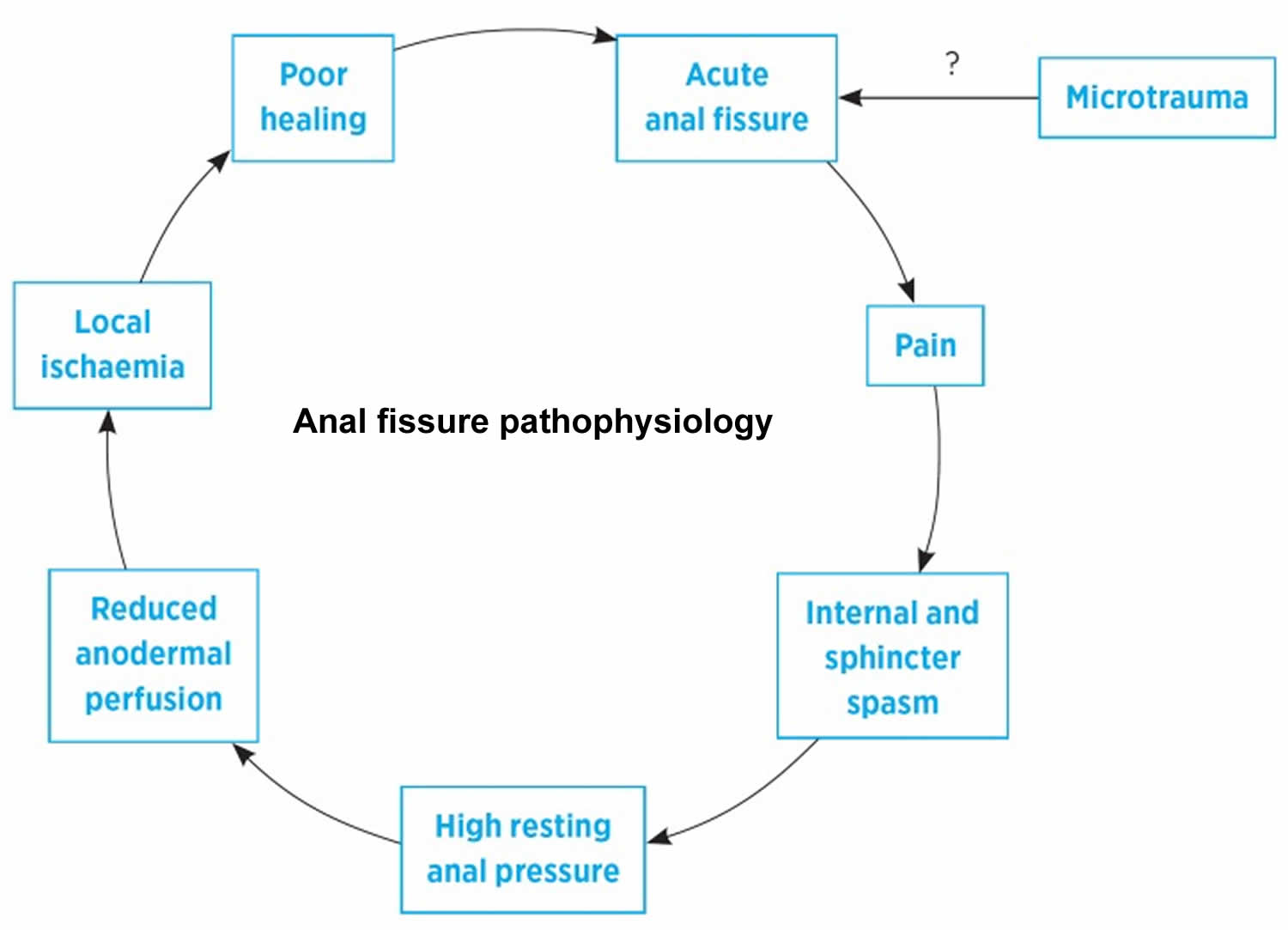

Anal fissure pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of anal fissures is not entirely clear. Anal fissure is probably due to an acute injury that leads to local pain and spasm of the internal anal sphincter. This spasm and the resulting high resting anal sphincter pressure 12 leads to reduced blood flow and ischemia 13 and poor healing. Unless this cycle is broken the fissure will persist (Figure 4).

In approximately 90% of patients the anal fissure is located in the posterior midline. It is hypothesized that this predilection for the posterior midline may occur because this portion of the anal canal is poorly perfused 14. Anterior anal fissures affect approximately 10% of patients and may have a different pathophysiology. They are associated with younger, mostly female, patients often with injury to or dysfunction of the external anal sphincter 7. In less than 1% of patients the fissures are lateral or multiple 15. Irrespective of these differences, posterior and anterior anal fissures are thought to be of primary cause, whereas lateral or multiple fissures are more likely to be secondary in nature 15.

A small study of completely excised anal fissures found no underlying microscopic features of inflammation in most of the patients. Furthermore, these anal fissures or defects showed little in the way of ulcer characteristics and appeared to be more consistent with unstable anodermal scar tissue 16. Additional research is needed to understand the temporal relationship between poor perfusion and lack of inflammation, as well as to identify the best terminology to describe these lesions.

Figure 4. Anal fissure pathophysiology

[Source 11 ]Anal fissure prevention

You may be able to prevent an anal fissure by taking measures to prevent constipation or diarrhea. Eat high-fiber foods (such as fruit, vegetables and wholegrains), drink fluids and exercise regularly to keep from having to strain during bowel movements.

Anal fissure diagnosis

Your doctor will likely ask about your medical history including your toilet habits and perform a physical exam, including a gentle inspection of the anal region. Often the tear is visible by gently parting your buttocks. Usually this exam is all that’s needed to diagnose an anal fissure.

A digital rectal examination (DRE), where a doctor inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into your bottom to feel for abnormalities, is not usually used to diagnose anal fissures as it’s likely to be painful.

An acute anal fissure looks like a fresh tear, somewhat like a paper cut. A chronic anal fissure likely has a deeper tear, and may have internal or external fleshy growths. A fissure is considered chronic if it lasts more than eight weeks.

The fissure’s location offers clues about its cause. A fissure that occurs on the side of the anal opening, rather than the back or front, is more likely to be a sign of another disorder, such as Crohn’s disease. Your doctor may refer you for specialist assessment if they think something serious may be causing your fissure. Your doctor may recommend further testing if he or she thinks you have an underlying condition:

- Anoscopy. An anoscope is a tubular device inserted into the anus to help your doctor visualize the rectum and anus.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. Your doctor will insert a thin, flexible tube with a tiny video into the bottom portion of your colon. This test may be done if you’re younger than 50 and have no risk factors for intestinal diseases or colon cancer.

- Colonoscopy. Your doctor will insert a flexible tube into your rectum to inspect the entire colon. This test may be done if you are older than age 50 or you have risk factors for colon cancer, signs of other conditions, or other symptoms such as abdominal pain or diarrhea.

- Occasionally, a measurement of anal sphincter pressure may be taken for anal fissures that have not responded to simple treatments. This may include a more thorough examination of your bottom carried out using anaesthetic to minimize pain.

Anal fissure treatment

Most anal fissures heal within a few weeks if you take steps to keep your stool soft, such as increasing your intake of fiber and fluids. Soaking in warm water or sitz baths for 10 to 20 minutes several times a day, especially after bowel movements, can help relax the sphincter and promote healing. Some people with anal fissures may need medication or, occasionally, surgery.

If your baby has an anal fissure, be sure to change diapers frequently, wash the area gently and discuss the problem with your child’s doctor.

Anal fissure home remedy

Several home remedies may help relieve discomfort and promote healing of an anal fissure, as well as prevent recurrences:

- Add fiber to your diet. Eating about 25 to 30 grams of fiber a day can help keep stools soft and improve fissure healing. Fiber-rich foods include fruits, vegetables, nuts and whole grains. You also can take a fiber supplement. Adding fiber may cause gas and bloating, so increase your intake gradually.

- Drink adequate fluids. Fluids help prevent constipation.

- Avoid straining during bowel movements. Straining creates pressure, which can open a healing tear or cause a new tear.

- Sitz baths. A sitz bath is simply a warm water bath in which a person sits in water up to the hips that are often used for healing or cleansing purposes. You sit in the bath. The water covers only your hips and buttocks. The water may contain medicine. Don’t use soap or bubbles or any other products unless prescribed by your doctor. Relax in the sitz bath 2 to 3 times a day for about 10 minutes at a time.

Anal fissure medicine

Your doctor may recommend:

- Laxatives. Laxatives are a type of medicine that can help you poop more easily. Adults with an anal fissure will usually be prescribed bulk-forming laxative tablets or granules. These work by helping your poo retain fluid, making it softer and less likely to dry out. Children with an anal fissure are usually prescribed an osmotic laxative oral solution. This type of laxative works by increasing the amount of fluid in the bowels, which stimulates the body to need to poop. Your doctor may recommend starting treatment at a low dose and gradually increasing it every few days until you’re able to pass soft poo every 1 or 2 days.

- Painkillers. If you have prolonged burning pain after having a poop, your doctor may recommend taking common painkillers, such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) or ibuprofen, which you can buy from a pharmacy or supermarket. If you decide to take these medicines, make sure you follow the dosage instructions on the patient information leaflet or packet.

- Externally applied glyceryl trinitrate or nitroglycerin (Rectiv), to help increase blood flow to the anal fissure and promote healing and to help relax the anal sphincter. Nitroglycerin ointment usually twice a day is generally considered the medical treatment of choice when other conservative measures fail. You’ll usually have to use nitroglycerin ointment for at least 6 weeks, or until your fissure has completely healed. The majority of acute fissures (present for less than 6 weeks) will heal with nitroglycerin treatment. Around 7 in every 10 chronic fissures heal with nitroglycerin therapy if used correctly. Side effects may include headache, which can be severe. Some people also feel dizzy or lightheaded after using the nitroglycerin ointment. If headaches are a problem, reducing the amount of ointment you use for a few days can help. Using a pea-sized amount of ointment 5 or 6 times a day is often better than using a larger amount twice a day. Nitroglycerin is not suitable for children or pregnant or breastfeeding women.

- Topical anesthetic creams such as lidocaine hydrochloride (Xylocaine) may be helpful for pain relief. A topical anaesthetic is one you rub directly into the affected area. It will not help fissures heal, but it can help ease the pain. Lidocaine is the most commonly prescribed topical anaesthetic for anal fissures. It comes in the form of either a gel or an ointment, and is usually only used for a short time (a few days).

- Calcium channel blockers usually used to treat high blood pressure (hypertension), such as oral nifedipine (Procardia) or diltiazem (Cardizem) can help relax the anal sphincter. These medications may be taken by mouth or applied externally and may be used when nitroglycerin is not effective or causes significant side effects. Topical calcium channel blockers work by relaxing the sphincter muscle and increasing blood supply to the fissure (similar to nitroglycerin). Topical calcium channel blockers are thought to be about as effective as nitroglycerin ointment for treating anal fissures, and may be recommended if other medicines have not helped. As with nitroglycerin ointment, you’ll usually have to use calcium channel blockers for at least 6 weeks, or until your fissure has completely healed. Side effects can include headaches, dizziness, and itchiness or burning at the site when you use the medicine. Any side effects should pass within a few days once your body gets used to the medicine.

- Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) injection, to paralyze the anal sphincter muscle and relax spasms. Botulinum toxin is a relatively new treatment for anal fissures. It’s usually used if other medicines have not helped. Botulinum toxin is a powerful poison that’s safe to use in small doses. If you have an anal fissure, an injection of the botulinum toxin can be used to paralyze your sphincter muscle. This should prevent the muscle from spasming, helping reduce pain and allowing the fissure to heal. It’s not clear exactly how effective botulinum toxin injections are for anal fissures, but research suggests they’re helpful for more than half the people who have them. This is similar to having treatment with nitroglycerin ointment and topical calcium channel blockers. The effects of botulinum toxin injections last for around 2 to 3 months, which should normally allow enough time for the fissure to heal.

Anal fissure surgery

If you have a chronic anal fissure that is resistant to other treatments, or if your symptoms are severe, your doctor may recommend surgery. Doctors usually perform a procedure called lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), which involves cutting a small portion of the anal sphincter muscle to reduce spasm and pain, and promote healing. A lateral sphincterotomy (LIS) is one of the most effective treatments for anal fissures, with a good track record of success. Most people will fully heal within 2 to 4 weeks. Studies have found that for chronic anal fissure, surgery is much more effective than any medical treatment. However, surgery has a small risk of causing loss of bowel control (bowel incontinence).

Advancement flaps

Advancement anal flaps involve taking healthy tissue from another part of your body and using it to repair the fissure and improving the blood supply to the site of the fissure. Advancement anal flaps may be recommended to treat long-term (chronic) anal fissures caused by pregnancy, or an injury to the anal canal.

Endorectal advancement flaps typically involved a subcutaneous flap with an incision made from the anal verge extending caudally. The skin flap is then advanced into the anal canal and positioned to cover the anal fissure and sutured in place. Two independent studies showed a 98% success rate with advancement anoplasty for the treatment of chronic anal fissure, irrespective of anal tone 17, 18. One prospective randomized trial of lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) versus advancement flap found no significant difference in healing rates (100% in the sphincterotomy group vs. 85% in the flap group) 19. Incontinence was not observed in either group. The advancement flap is an appropriate alternative to lateral internal sphincterotomy and may be particularly helpful in patients with low-pressure fissures. More data are needed before it can be recommended as first-line therapy.

Fissurectomy

Fissurectomy entails excision of the chronic granulation tissue, hypertrophied papilla, and scar, and is either left open or closed primarily 16. In one clinical trial by Mousavi et al 20, fissurectomy was considered inferior to lateral internal sphincterotomy. Another study by Lindsey et al 21 combined fissurectomy with botulinum toxin injection and had a 93% healing rate with only transient incontinent to flatus in 7%. Badejo 22 reported 100% healing rate at 2 weeks with no complications and no recurrences at 1-year follow-up. These results have not been duplicated in any other study. In general, fissure excision does not improve healing rates when combined with lateral sphincterotomy (LIS), and may lead to unnecessary risks of incontinence.

Chronic fissure treatment

Chronic anal fissure is typically more difficult to treat, given recurrence and complications. Aside from using nitrates and calcium channel blockers, a third pharmacological method can be employed to prevent a recurrence of chronic anal fissure. Botulinum toxin (Botox) is generally considered safe and provides significant pain relief. Compared to nitrates and calcium channel blockers, botulinum toxin (Botox) is superior and the most effective.

Lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) is considered the ‘gold standard’ therapy for chronic anal fissure and relieves symptoms with a high rate of healing and less than 10% long term recurrence 11. Lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) has, however, been associated with the development of a period of transient postoperative anal incontinence in 30% (or even more) patients which can become permanent 23, 24. Anal incontinence (including uncontrolled flatus, mild stool, soiling, and gross incontinence) is the major complication; it occurs in approximately 45% of patients in the immediate postoperative period with a higher likelihood in females (50% versus 30% in males) 2. Within five years of lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), the rate of incontinence is substantially reduced to less than 10%, with a gross loss of solid stool being less than 1% 2. Recurrence of chronic anal fissure in post-lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) patients is approximately 5%, in which conservative methods with pharmacological treatment cures approximately 75% 2.

Other acute complications from lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) surgery include excessive bleeding, encountered more commonly during the open technique, and may require suture ligation. Approximately 1% of patients undergoing the closed technique develop a perianal abscess, primarily because of the dead space created by the separation of the anal mucosa.

One long-term complication of sphincterotomy encountered more frequently in the repair of posterior chronic anal fissures is a keyhole deformity. A keyhole deformity is usually asymptomatic and is well tolerated by patients. In a study of over 600 patients undergoing internal sphincterotomy, only 15 developed a keyhole deformity, which was not associated with any anal incontinence, but went on to receive the repair.

In a study conducted between 1984 and 1996, 96% of patients undergoing lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) had complete resolution of their chronic anal fissure within three weeks. An open and closed technique can be used in this procedure, under either local or general anesthesia. It has been found that those undergoing lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) with local anesthesia have a higher rate of recurrence of chronic anal fissure 2. In the open technique of lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), an incision is made across the intersphincteric groove. Blunt dissection is then employed to separate the internal sphincter from the anal mucosa. Finally, the internal sphincter is divided with scissors. In the closed technique of lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), a small incision is made at the intersphincteric groove, and a scalpel is inserted parallel to the internal sphincter. The scalpel is advanced along the intersphincteric groove, and the internal sphincter is then divided by rotating the scalpel toward it. The healing rate is found to be the same with either an open or closed approach 2.

Novel therapies

In a pilot study of eight patients, autologous adipose tissue transplant has shown 75% healing of anal fissure and 80% resolution of anal stenosis in patients with chronic anal fissure who failed previous medical and surgical therapy 25.

In a recent pilot study five patients with chronic anal fissure underwent one temporary 8-electrode Octad lead for sacral nerve root stimulation 26. Stimulation was conducted for 20 minutes three times per day. The lead was removed after 3 weeks of stimulation. All patients had healing of the fissure by the end of the third week and no recurrence at 1-year follow-up 26.

Anal fissure prognosis

Acute anal fissures in low-risk patients typically do well with conservative management and resolve within a few days to a few weeks. However, a percentage of these patients go on to develop chronic anal fissure, which requires pharmacological treatment or surgical management. Over 90% of patients undergoing surgical management achieve cure within 3 to 4 weeks post-operatively 27. Anal fissures often come back. A fully healed fissure can come back after a hard bowel movement or trauma. Medical problems such as inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease), infections, or anal tumors can cause symptoms similar to anal fissures. If a fissure does not improve with treatment, it is important to be evaluated for other possible conditions.

Post-treatment prognosis

Most patients can return to work and go back to daily activities a few days after surgery. Complete healing after both medical and surgical treatments can take 6 to 10 weeks. Even when the pain and bleeding lessen, it is important to maintain good bowel habits and eat a high-fiber diet. Continued hard or loose bowel movements, scarring, or spasm of the internal anal muscle can delay healing.

- Botox injections are associated with healing of chronic anal fissures in 50% to 80% of patients.

- Lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS) is successful in more than 90% of patients. Although uncommon, this procedure may affect the patient’s ability to fully control gas or bowel movements (anal incontinence).

Living with anal fissures

Your doctor may prescribe stool softeners to make going to the bathroom easier and less painful while the fissure heals. Numbing cream can also make bowel movements less painful. Petroleum jelly, zinc oxide, 1% hydrocortisone cream, and products like Preparation H can help soothe the area. Instead of toilet paper, use alcohol-free baby wipes that are gentler on the area.

Sitz baths can help heal fissures and make you feel better. Fill the tub with enough lukewarm water to cover your hips and buttocks. Don’t use soap or bubbles or any other products unless prescribed by your doctor. Relax in the sitz bath 2 to 3 times a day for about 10 minutes at a time.

People who develop fissures once are more likely to have them in the future, so it’s important to keep bowel movements regular. If you’ve had a fissure in the past, you may be tempted to hold your bowel movement in to avoid the pain of passing it. But that’s not a good idea. That can make stools become hard and difficult to pass, which will make the fissure worse. Continue with a high-fiber diet and drink plenty of liquid to help make stools easy to pass.

References- Beaty, J. S., & Shashidharan, M. (2016). Anal Fissure. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 29(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1570390

- Jahnny B, Ashurst JV. Anal Fissures. [Updated 2021 Nov 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526063

- Barton J. Nitroglycerin and Lidocaine topical treatment for anal fissure. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002:April.

- Elía Guedea M, Gracia Solanas JA, Royo Dachary P, Ramírez Rodríguez JM, Aguilella Diago V, Martínez Díez M. Prevalencia de afección anal en el paciente superobeso mórbido tras bypass biliopancreático de Scopinaro [Prevalence of anal diseases after Scopinaro’s biliopancreatic bypass for super-obese patients]. Cir Esp. 2008 Sep;84(3):132-7. Spanish. doi: 10.1016/s0009-739x(08)72154-7

- Lund JN, Scholefield JH. Aetiology and treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1996 Oct;83(10):1335-44. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831006

- ((Brisinda G, Cadeddu F, Brandara F, Brisinda D, Maria G. Treating chronic anal fissure with botulinum neurotoxin. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004 Dec;1(2):82-9. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0048

- Schlichtemeier, S., & Engel, A. (2016). Anal fissure. Australian prescriber, 39(1), 14–17. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2016.007

- Choi, Y. S., Kim, D. S., Lee, D. H., Lee, J. B., Lee, E. J., Lee, S. D., Song, K. H., & Jung, H. J. (2018). Clinical Characteristics and Incidence of Perianal Diseases in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Annals of coloproctology, 34(3), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2017.06.08

- Siddiqui J, Fowler GE, Zahid A, Brown K, Young CJ. Treatment of anal fissure: a survey of surgical practice in Australia and New Zealand. Colorectal Dis. 2019 Feb;21(2):226-233. doi: 10.1111/codi.14466

- Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;109(8):1141-57; (Quiz) 1058. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.190

- Madalinski M. H. (2011). Identifying the best therapy for chronic anal fissure. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics, 2(2), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v2.i2.9

- Keck JO, Staniunas RJ, Coller JA, Barrett RC, Oster ME. Computer-generated profiles of the anal canal in patients with anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995 Jan;38(1):72-9. doi: 10.1007/BF02053863

- Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ. Relationship between anal pressure and anodermal blood flow. The vascular pathogenesis of anal fissures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994 Jul;37(7):664-9. doi: 10.1007/BF02054409

- Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ, De Graaf EJ. Ischaemic nature of anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1996 Jan;83(1):63-5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830120

- Zaghiyan, K. N., & Fleshner, P. (2011). Anal fissure. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 24(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1272820

- Engel AF, Eijsbouts QA, Balk AG. Fissurectomy and isosorbide dinitrate for chronic fissure in ano not responding to conservative treatment. Br J Surg. 2002 Jan;89(1):79-83. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01958.x

- Giordano P, Gravante G, Grondona P, Ruggiero B, Porrett T, Lunniss PJ. Simple cutaneous advancement flap anoplasty for resistant chronic anal fissure: a prospective study. World J Surg. 2009 May;33(5):1058-63. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9937-1

- Chambers W, Sajal R, Dixon A. V-Y advancement flap as first-line treatment for all chronic anal fissures. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010 May;25(5):645-8. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0881-1

- Leong AF, Seow-Choen F. Lateral sphincterotomy compared with anal advancement flap for chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995 Jan;38(1):69-71. doi: 10.1007/BF02053862

- Mousavi SR, Sharifi M, Mehdikhah Z. A comparison between the results of fissurectomy and lateral internal sphincterotomy in the surgical management of chronic anal fissure. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009 Jul;13(7):1279-82. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0908-5

- Lindsey I, Cunningham C, Jones OM, Francis C, Mortensen NJ. Fissurectomy-botulinum toxin: a novel sphincter-sparing procedure for medically resistant chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 Nov;47(11):1947-52. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0693-x

- Badejo OA. Outpatient treatment of fissure-in-ano. Trop Geogr Med. 1984 Dec;36(4):367-9.

- Brown CJ, Dubreuil D, Santoro L, Liu M, O’Connor BI, McLeod RS. Lateral internal sphincterotomy is superior to topical nitroglycerin for healing chronic anal fissure and does not compromise long-term fecal continence: six-year follow-up of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Apr;50(4):442-8. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0844-3

- Arroyo A, Pérez F, Serrano P, Candela F, Calpena R. Open versus closed lateral sphincterotomy performed as an outpatient procedure under local anesthesia for chronic anal fissure: prospective randomized study of clinical and manometric longterm results. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Sep;199(3):361-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.04.016

- Lolli P, Malleo G, Rigotti G. Treatment of chronic anal fissures and associated stenosis by autologous adipose tissue transplant: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 Apr;53(4):460-6. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b726b2

- Yakovlev A, Karasev SA, Dolgich OY. Sacral nerve stimulation: a novel treatment of chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Mar;54(3):324-7. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318202f922

- Brady JT, Althans AR, Neupane R, Dosokey EMG, Jabir MA, Reynolds HL, Steele SR, Stein SL. Treatment for anal fissure: Is there a safe option? Am J Surg. 2017 Oct;214(4):623-628. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.004