Anal fistula

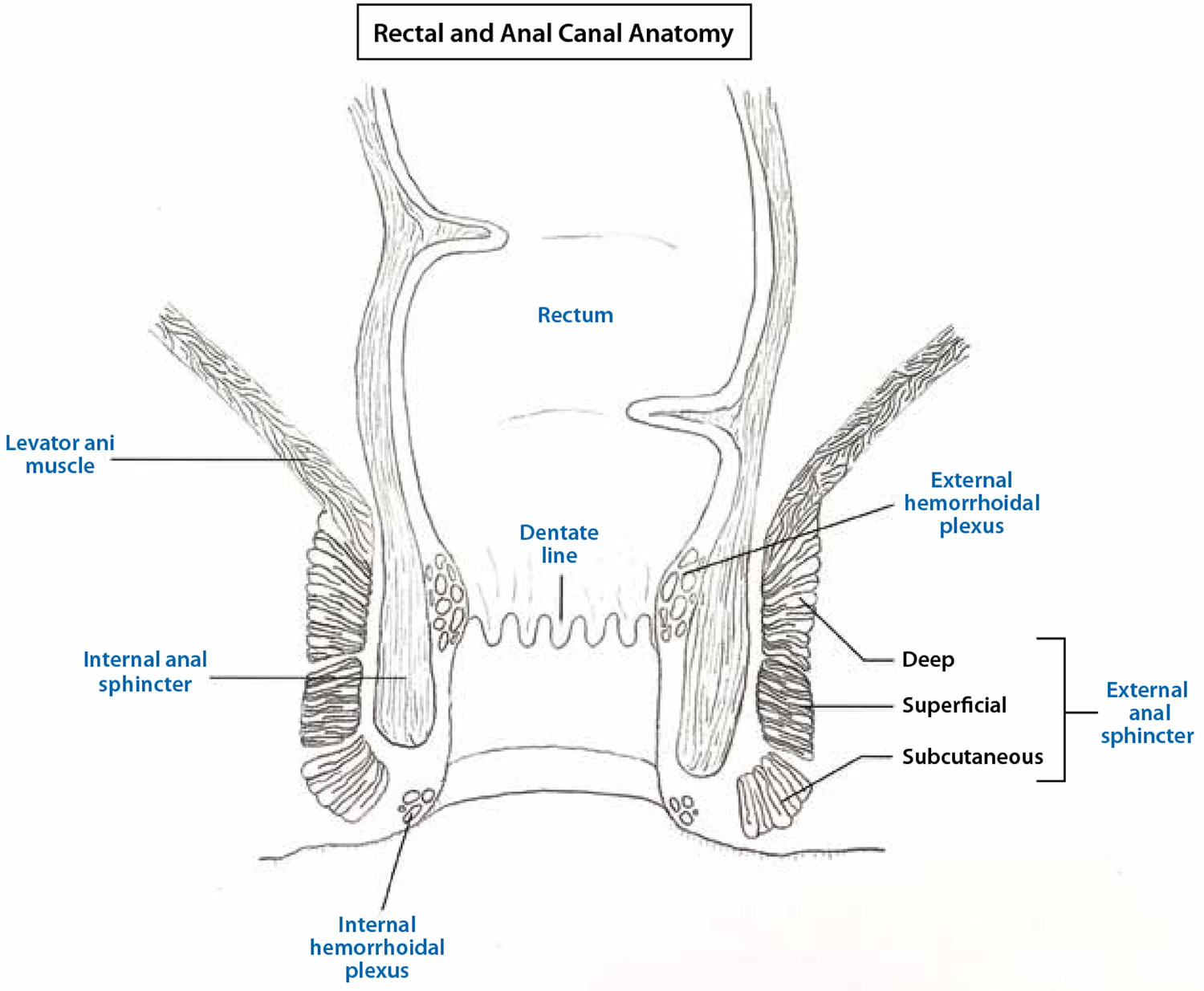

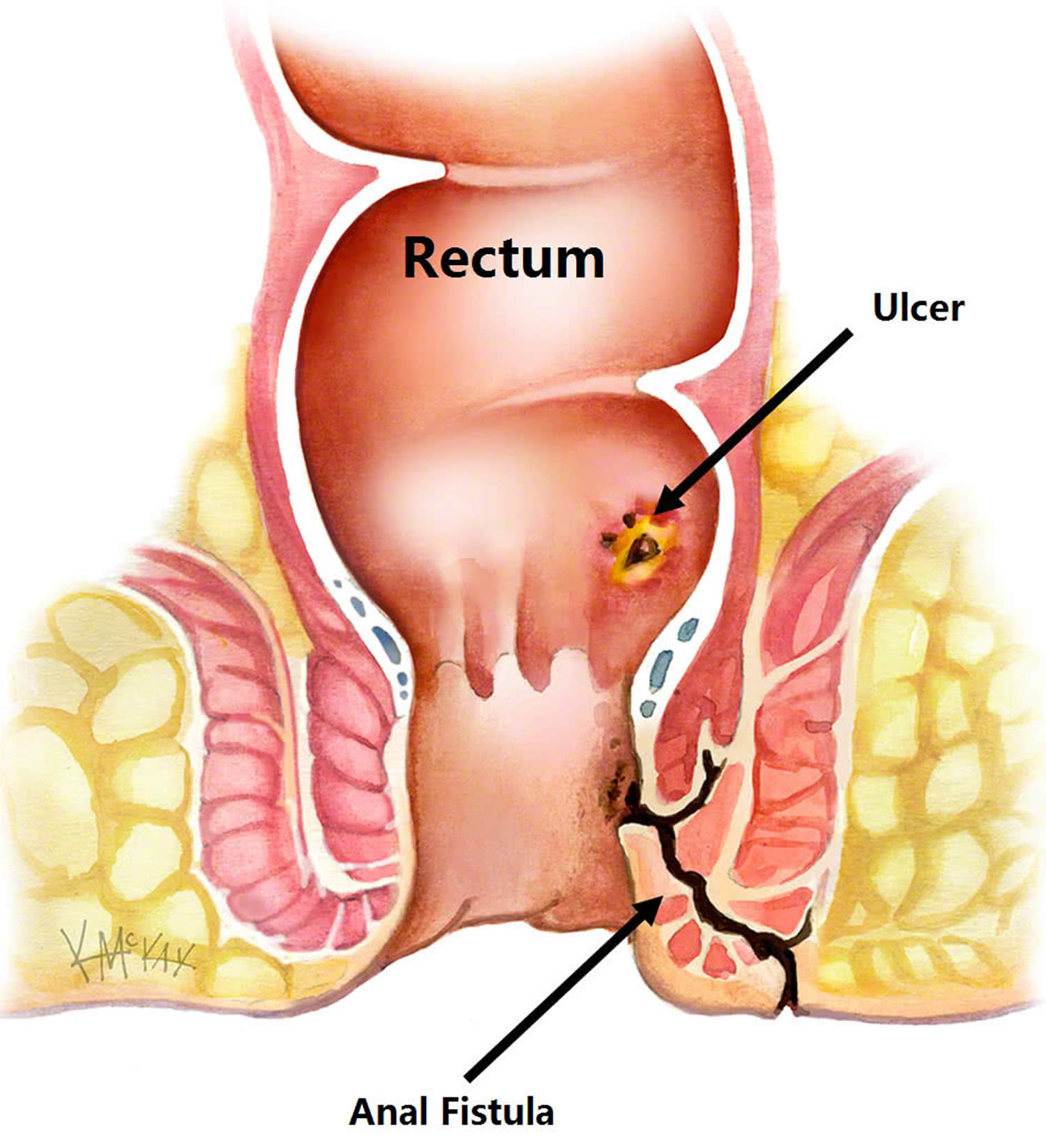

Anal fistula also commonly called fistula-in-ano or perianal fistula, is a small infected tunnel that develops between the anal canal and the perianal skin (the skin near the anus where poop leaves the body) (see Figure 2) 1. The majority of anal fistula are usually the result of an infection near the anus causing a collection of pus (abscess) near the anus or rectum 2. Most anal fistulas (approximately 90% of cases) are idiopathic and are the result of an infection that starts in an anal gland (Figure 3) 3, 4. This infection results in an anal abscess that drains spontaneously or is drained surgically through the skin next to the anus, leaving a communicating tract between the internal anus and the external skin of the perianal region. The fistula then forms a tunnel under the skin and connects with the infected gland. Men are more commonly affected by anal fistulas than women 5 and the mean age of first presentation is reported to be 40 years 6.

The prevalence of anal fistula is reported to be approximately 1-2 per 100,00 patients in European population studies 7. The mean incidence of anal fistula is estimated to be 8.6 per 100,000 people, 1.04 per 10,000 people, and 2.32 per 10,000 people in Finland, Spain and Italy, respectively 5. However, being more than 10 years old, these reports may be outdated. A recent systematic review estimates the prevalence of anal fistula in Europe as 1.69 per 10,000 patients 8.

Anal fistulas are also associated with Crohn’s disease, lymphogranuloma venereum, hidradenitis suppurativa, surgery, radiotherapy and sexually transmitted diseases 9, as these can result in deep rectal/anal mucosal damage, which facilitates the development of fistula. Epidemiological reports on these and other relevant comorbid conditions in anal fistula are sparse. In Crohn’s disease, the cumulative incidence of anal fistula ranges between 17% and 50%, with about 35% of patients having at least one anal fistula during the course of the disease 10. Anal fistulas reported to be associated with tuberculosis are 0.2%, and 3.3% are associated with trauma 5. After surgery, between 1.2% of patients and 0.3% of patients develop anal fistula 11, 12. Approximately 7% of patients with lymphogranuloma venereum 13 and 80%-91% of patients with anorectal tuberculosis present with anal fistula 14.

Patients with chronic diseases like diabetes mellitus are also discussed to be at increased risk of anal fistula, due to their susceptibility to skin lesions and systemic infections 15 and increased risk for perianal abscesses.

Anal fistulas can cause unpleasant symptoms, such as local pain, itching, a chronic discharge of pus draining from the fistulous tract that typically has an offensive odor, which affects your daily activities and occasional bleeding and will not usually get better on their own.

Surgery is usually necessary to treat an anal fistula as they usually do not heal by themselves 16.

There are several different perianal fistula surgery procedures. The best option for you will depend on the position of your anal fistula and whether it’s a single channel or branches off in different directions. Sometimes you may need to have an initial examination of the area under general anesthetic (where you’re asleep) to help determine the best treatment.

Total sphincter preservation surgery has gradually become the first choice for anal fistula treatment 16. In the past few decades, several sphincter-sparing techniques have been established, including fistulotomy, Seton, endorectal advancement flap (ERAF), ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), fibrin glue, anal fistula plug, fistula laser closure, video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT), and adipose-derived stem cells. Based on these independent sphincter-sparing techniques, to further diminish the recurrence rate, protect the anal sphincter and obtain better postoperative outcomes, some innovative, combined, and modified new therapies have been proposed and applied in clinical studies in recent years. However, due to the diversity of treatment methods and the inevitable heterogeneity of clinical trials, their variable outcomes are prone to generate confusion and misunderstanding. Your colorectal surgeon will talk to you about the options available and which one they feel is the most suitable for you. In Crohn’s disease patients, first-line treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor α antibody is recommended 1.

Surgery for an anal fistula is usually carried out under general anesthetic. In many cases, it’s not necessary to stay in hospital overnight afterwards.

The aim of surgery is to heal your anal fistula while avoiding damage to the anal sphincter muscles, the ring of muscles that open and close the anus, which could potentially result in loss of bowel control (bowel incontinence).

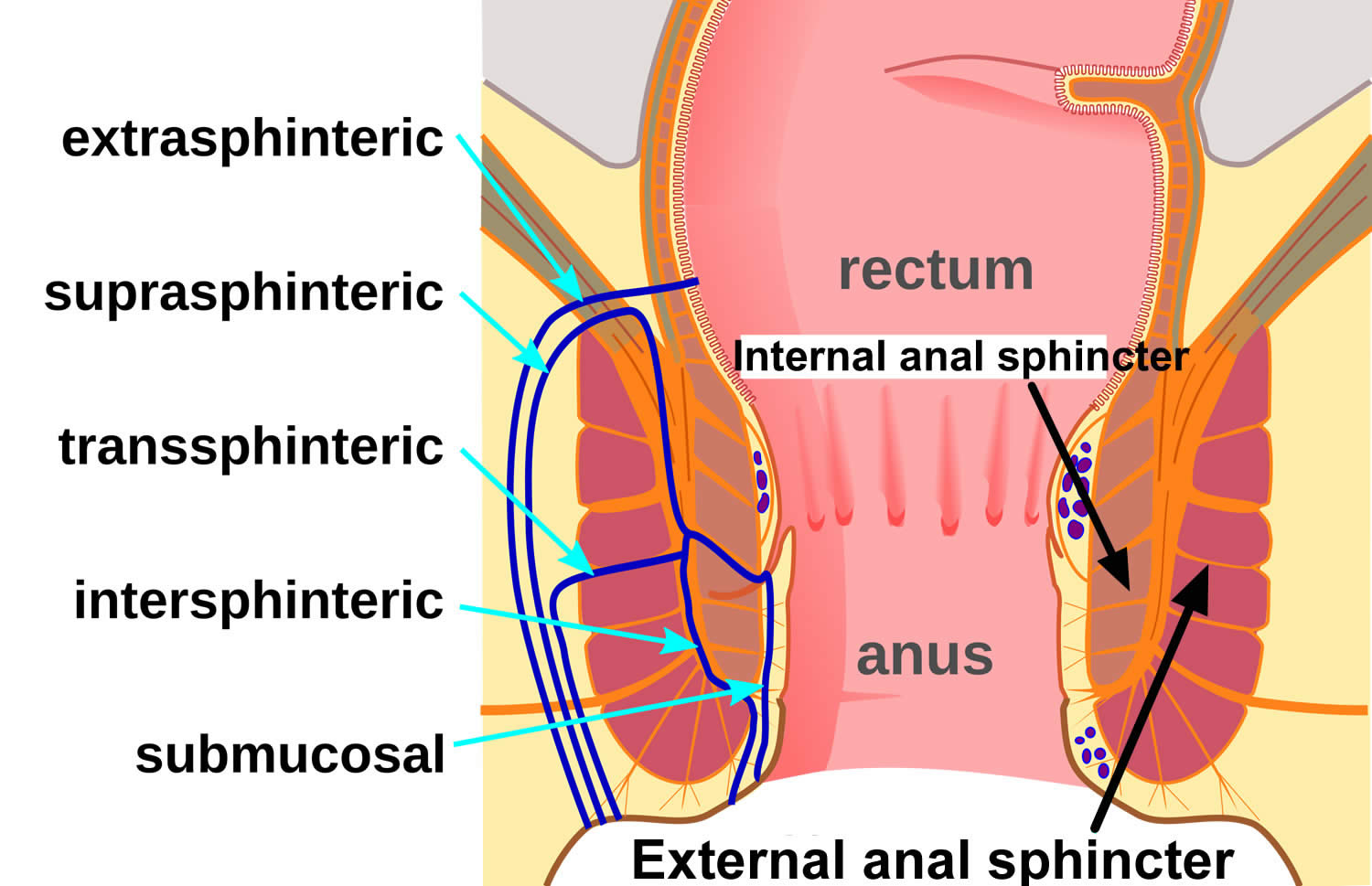

Figure 1. Rectal and anal canal anatomy

Figure 2. Anal fistula

Figure 3. Anorectal fistula

What is the recovery like from anal fistula surgery?

Pain after surgery is controlled with pain pills, fiber and bulk laxatives. Patients should plan for time at home using sitz baths and avoiding the constipation that can be associated with prescription pain medication. Discuss with your surgeon the specific care and time away from work prior to surgery to prepare yourself for post-operative care.

Can anal fistula recur?

Up to 50% of abscesses may re-present as another abscess or as a frank fistula. Despite proper treatment and apparent complete healing, fistulas can potentially recur, with recurrence rates dependent upon the particular surgical technique utilized. Should similar symptoms arise, suggesting recurrence, it is recommended that you find a colon and rectal surgeon to manage your condition.

A large meta-analysis examined risk factors for recurrence of anal fistula after fistula surgery included a high transanal fistula, horseshoe extensions, and multiple fistula tracts as well as the patient having a history of anal procedures or not identifying the internal opening of the fistula intraoperatively 17. In a study of 251 patients who had high transphincteric fistulas and were treated with loose setons history of fistula surgery, horseshoe fistula, and anterior fistula were risk factors of recurrence 18.

Types of anal fistula

Anal fistula can be short and superficial, not involving the anal sphincter (submucosal fistula) or can be long and deep, involving the just the internal anal sphincter (intersphincteric fistula) or both anal sphincters (transphincteric fistula or extrasphincteric). Most fistulae are low arising from low within the anal canal. Rarely fistulas are high, arising from above the anal canal (supralevator fistula).

Anal fistula can be divided into simple and complex types according to the degree of lesions. According to the classification standards of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), simple anal fistula includes low transphincteric, and intersphincteric fistulas that cross 30% of the external sphincter. Regarding simple anal fistula, especially distal cases, fistulotomy can be used to obtain ideal treatment results 19. However, complex anal fistula is one of the refractory diseases encountered in colorectal surgery; it is transphincteric fistula that account for more than 30% of sphincter complex,. Fistulas are complex if the primary track includes high transsphincteric fistulas with or without a high blind tract, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric fistulas, horseshoe fistulas, multiple tracks, anteriorly lying track in a female patient, and those associated with inflammatory bowel disease, radiation, malignancy, preexisting fecal incontinence or chronic diarrhea.

Simple anal fistula

Simple anal fistula are those with a single tract that involves less than 30-50% of the external anal sphincter. The preferred treatment of a simple ana fistula is to lay it open 20. This is a small operation under general anesthetic, in which a probe is placed in the fistula, and the overlying skin cut to allow the tract to heal as a shallow ulcer.

Complex anal fistula

Complex anal fistula are those with multiple tracts, those that involve more than 30-50% of the external sphincter, those that involve the anterior half of the anus (in women), any fistula as a result of radiation or Crohn’s disease, and those arising in someone with already compromised sphincter function (i.e. weak anal tone prone to incontinence). These cannot simply be laid open, and often the first step is to control the sepsis by inserting a seton.

Perianal fistula classification

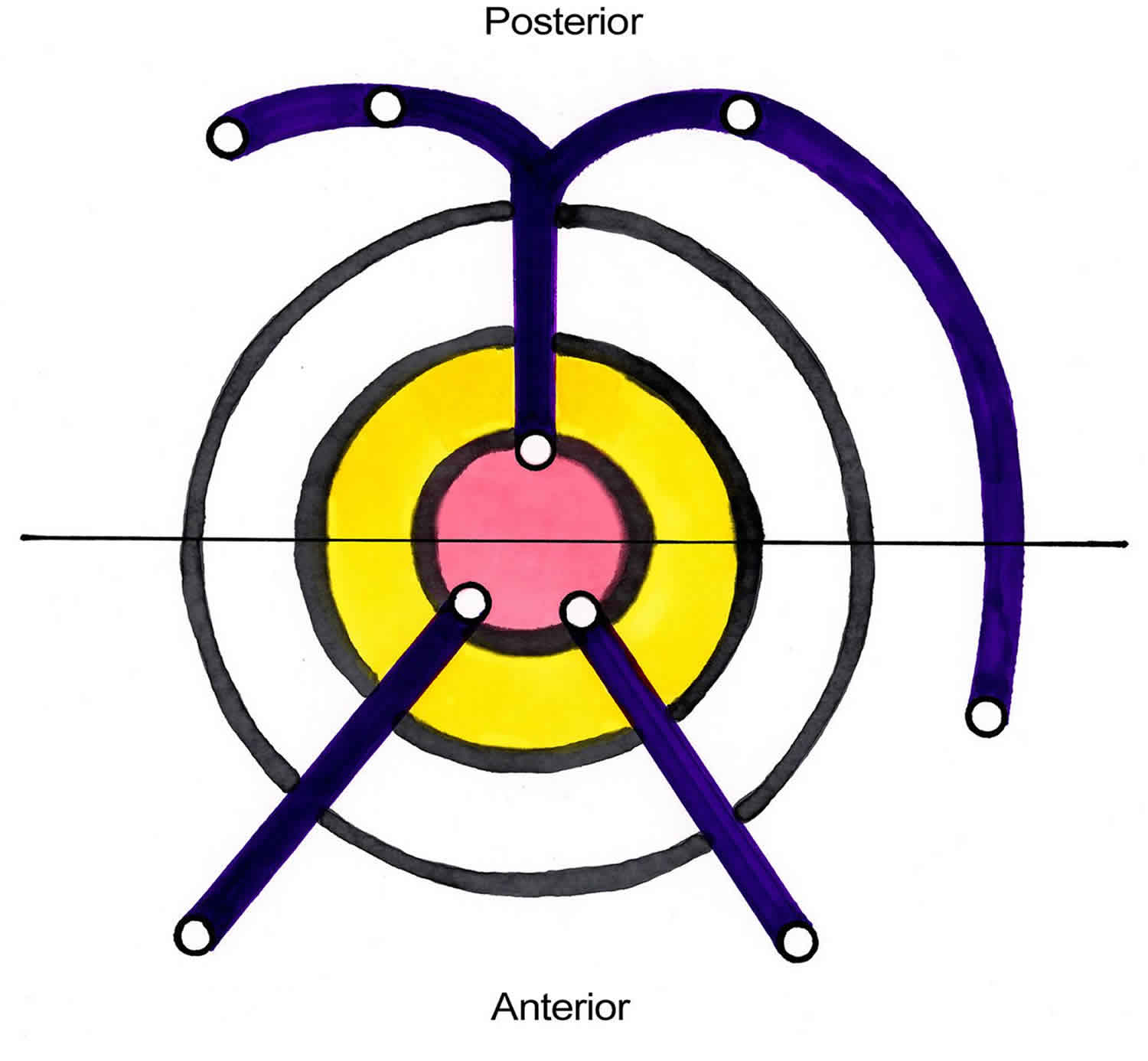

The Goodsall rule can help anticipate the anatomy of a perianal fistula. The Goodsall rule states that perianal fistulas with an external opening anterior to a plane passing transversely through the center of the anus will follow a straight radial course to the dentate line. Fistulas with their openings posterior to this line will follow a curved course to the posterior midline (see Figure 4). Exceptions to this rule are external openings lying more than 3 cm from the anal verge. These almost always originate as a primary or secondary tract from the posterior midline, consistent with a previous horseshoe abscess 21.

Figure 4. Perianal fistula Goodsall rule

Parks classification system

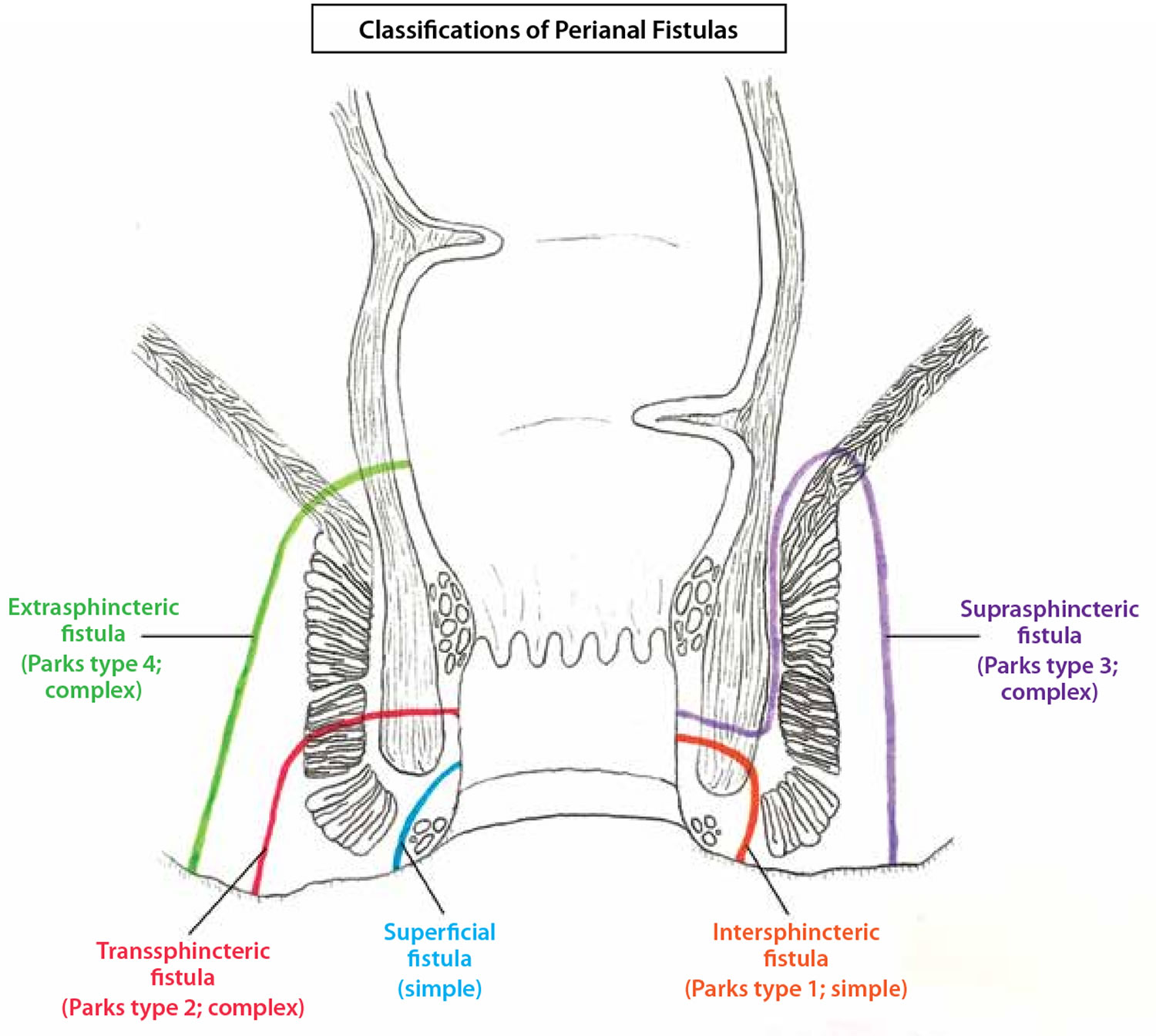

The classification system developed by Parks, Gordon, and Hardcastle (generally known as the Parks classification) is the one most commonly used for perianal fistula. The Parks classification categorizes perianal fistulas based on their relationship to the external and internal anal sphincters (Figures 1 and 3) 22. The Parks classification system (Figure 3 below) defines four types of perianal fistula or fistula-in-ano that result from cryptoglandular infections, as follows 23:

- Intersphincteric

- Transsphincteric

- Suprasphincteric

- Extrasphincteric

Figure 5. Parks classification of perianal fistula

Footnote: The Parks classification of perianal fistulas illustrates a superficial fistula, intersphincteric fistula (type 1), transsphincteric fistula (type 2), suprasphincteric fistula (type 3), and extrasphincteric fistula (type 4) in relation to the internal and external anal sphincter muscles. A revised classification from the American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review Panel defines perianal fistulas as simple or complex.

[Source 24 ]Intersphincteric perianal fistula

Intersphincteric fistulas is one that crosses the internal sphincter and then has a tract to the outside of the anus. Intersphincteric fistulas are the most common type of fistula comprising 50-80% of all cryptoglandular fistulas.

An intersphincteric perianal fistula is characterized as follows:

- Intersphincteric perianal fistula is the result of a perianal abscess

- Common course – It begins at the dentate line, then tracks via the internal sphincter to the intersphincteric space between the internal and external anal sphincters, and finally terminates in the perianal skin or perineum

- Incidence – 70% of all anal fistulas

- Other possible tracts – No perineal opening; high blind tract; high tract to lower rectum or pelvis

Transsphincteric perianal fistula

Trans is a Latin word for “on the other side of.” So a trans-sphincteric fistula is one that crosses to the other side of the external sphincter before exiting in the perianal area and thus involving both the internal and external anal sphincters.

A transsphincteric perianal fistula is characterized as follows:

- In its usual variety, transsphincteric perianal fistula results from an ischiorectal fossa abscess

- Common course – It tracks from the internal opening at the dentate line via the internal and external anal sphincters into the ischiorectal fossa and then terminates in the perianal skin or perineum

- Incidence – 25% of all anal fistulas

- Other possible tracts – High tract with perineal opening; high blind tract

Suprasphincteric perianal fistula

Suprasphincteric fistula tracts travel superior to the external sphincter and cross the puborectal muscle before changing course caudal to their external opening. Accordingly, they pass the internal anal sphincter and the puborectal muscle but spare the external anal sphincter. When these patients typically present with a perirectal abscess, it may not be visible on inspection, but they will have tenderness on the digital rectal exam.

A suprasphincteric perianal fistula is characterized as follows:

- Suprasphincteric perianal fistul arises from a supralevator abscess

- Common course – It passes from the internal opening at the dentate line to the intersphincteric space, tracks superiorly to above the puborectalis, and then curves downward lateral to the external anal sphincter into the ischiorectal fossa and finally to the perianal skin or perineum

- Incidence – 5% percent of all anal fistulas

- Other possible tracts – High blind tract (ie, palpable through rectal wall above dentate line)

Extrasphincteric perianal fistula

Extrasphincteric fistulas often arise in the more proximal rectum rather than the anus and are often a complication of a procedure. Their external opening is in the perianal area and the tract courses superiorly to enter the anal canal above the dentate line.

An extrasphincteric perianal fistula is characterized as follows:

- Extrasphincteric perianal fistula may arise from foreign body penetration of the rectum with drainage through the levators, from penetrating injury to the perineum, from Crohn disease or carcinoma or its treatment, or from pelvic inflammatory disease

- Common course – It runs from the perianal skin via the ischiorectal fossa, tracking upward and through the levator ani muscles to the rectal wall, completely outside the sphincter mechanism, with or without a connection to the dentate line

- Incidence – 1% of all anal fistulas

Current procedural terminology codes classification

Current procedural terminology coding includes the following:

- Subcutaneous

- Submuscular (intersphincteric, low transsphincteric)

- Complex, recurrent (high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric, multiple tracts, recurrent)

- Second stage

Unlike the current procedural terminology coding, the Parks and colleagues classification system developed by Parks et al 23 does not include the subcutaneous fistula. These fistulas are not of cryptoglandular origin but are usually caused by unhealed anal fissures or anorectal procedures (eg, hemorrhoidectomy or sphincterotomy).

Anal fistula signs and symptoms

Symptoms of an anal fistula can include:

- skin irritation around the anus

- a constant, throbbing pain that may be worse when you sit down, move around, poo or cough

- smelly discharge from near your anus

- passing pus or blood when you poop

- swelling and redness around your anus and a high temperature (fever) if you also have an abscess

- difficulty controlling bowel movements (bowel incontinence) in some cases

The end of the fistula might be visible as a hole in the skin near your anus, although this may be difficult for you to see yourself.

Anal fistula causes

Most anal fistulas are idiopathic (approximately 90% of cases), and is thought to originate from a blockage of the anal glands and crypts. Obstruction of the anal glands allows bacteria to proliferate and ultimately forms a perirectal or anorectal or perianal abscess. With or without surgical treatment of the anorectal abscess, there is a significant risk of fistula formation. In addition to an incision and drainage, a 5 to 10-day course of antibiotics has been shown to decrease the rate of fistula formation 25.

Less common causes of anal fistulas include:

- Crohn’s disease – a long-term condition in which the digestive system becomes inflamed

- Diverticulitis – infection of the small pouches that can stick out of the side of the large intestine (colon)

- Hidradenitis suppurativa – a long-term skin condition that causes abscesses and scarring

- Infection with tuberculosis (TB) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with or without AIDS, are predisposed to anorectal disease and anal fistulas. These fistulas may lack internal openings and are sometimes in the absence of an underlying abscess 26. In one study, fistula-in-ano accounted for 6% anorectal pathologies in HIV patients and was irrespective of the utilization of antiretroviral therapy 27.

- Complication of surgery near the anus

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) of the anus and rectum, usually secondary to anal receptive intercourse, may predispose individuals to perianal abscess and fistula. These anorectal STIs are most commonly caused by gonorrhea, chlamydia as well as, syphilis (Treponema pallidum) and herpes simplex 28.

- Radiation proctitis is another cause of anal fistulas. Radiation proctitis requires surgical intervention in less than 10% of the cases with fistula tracks to the vagina, urethra, and bladder being a common complication. Impaired microvascular healing often requires multiple treatment modalities, including local excision, flap reconstruction, and diversion of stool or urine from the site 29.

- Complicated vaginal deliveries with 3rd or 4th-degree tears or requirement of episiotomy may predispose to anal fistula; however, these fistulas often heal spontaneously. In nonhealing obstetric related anal fistulas, surgical therapy is dependent on the location of the fistula as well as vaginal involvement. When distal to the dentate line, a recto-vaginal fistula becomes an ano-rectovaginal fistula. Causes include obstetrical trauma typically associated with a traumatic vaginal birth. Patients who undergo episiotomy are at increased risk for sphincter injury and fecal incontinence 30.

Anal fistula results when an anal abscess bursts into the tissues surrounding the anus. This condition is common in young adults, but can occur at any age. The reason why some people develop a fistula, and others don’t is not known.

The crypto-glandular theory espoused by Eisenhammer 31 and Parks 32 remains the most plausible explanation for the initiating event in most cases of idiopathic anal sepsis, and is widely accepted 20. This theory proposes that sepsis originates as an infection in an obstructed anal gland, usually lying in the intersphincteric space. Mitalas et al. 33 performed histological studies on the fistula track in a series of nine patients with chronic fistula undergoing exploration of the intersphincteric space. None of the tracks contained evidence of anal gland tissue with mucin-producing cells. However, this does not disprove the theory, as it is quite plausible that glandular epithelium was obliterated during the original septic process. Whereas there has not been any recent publication confirming this theory, equally there has not been a publication proposing a more plausible explanation. Naldini et al. 34 performed endoanal ultrasound scans on 175 patients with a chronic anal fissure. They demonstrated an intersphincteric fistula in 91 (53%) patients and a transsphincteric fistula in 21 (12%) patients 34. The relevance of this finding is uncertain. Whilst it suggests a possible alternative cause for an anal fistula, its relevance is more likely to be an explanation for chronicity of an anal fissure 20. Why some people are more prone to anal sepsis remains unexplained. Smoking and Crohn’s disease have both been shown to increase your risk of developing a fistula. The success of surgery for the treatment of fistulae due to Crohn’s disease or in the smoker is considerably lower than for other fistulas. Smoking within the last year seems to double the risk of anal sepsis, but this effect disappears 5 years after cessation of smoking 35. What is less clear is the explanation for persistence of the sepsis with formation of a fistula. Infliximab infusions have been shown to increase the success of fistula closure in Crohn’s disease 36.

Whilst the cryptoglandular theory assumes that an anal fistula has arisen from the spread of infection from an anal gland, the rate of fistula formation following presentation with an anal abscess is low. Two recent series have reported similar findings, with only a third of patients presenting with an abscess going on to form an anal fistula 37, 38. Furthermore, neither study identified any associated features that might have increased the risk of fistula formation, which was lower in diabetic patients 37, 38. A lower rate of 15.5% for fistula formation following an acute anal abscess has been calculated from hospital activity data 39, although this only included patients undergoing surgery for an anal fistula and it is likely that the overall rate is higher as patients not seeking further medical attention would not have been captured by this data set. Why some patients go on to establish a fistula remains uncertain; possible reasons include persistent sepsis, epithelialization of the track and hormone-mediated host response 20. Traditionally it has been assumed that persistence of sepsis drives fistula formation. However, earlier studies have shown a paucity of organisms in a fistula track 40, 41 and more recent studies using molecular techniques have shown a lack of bowel-related organisms in the fistula track. Tozer et al. 42 used in situ hybridization to study the microflora of 18 idiopathic (cryptoglandular) fistulas. Surprisingly, bacteria were not found in close association with the luminal surface of any fistula track. Similarly, in a series of 10 patients with transsphincteric fistulas, van Onkelen et al. 43 failed to identify bacteria in the fistula track using 16S rRNA sequencing in nine patients. However, immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of bacterial-derived proinflammatory peptidoglycans in all bar one fistula, with evidence of host response in 6 out of 10. This raises the possibility that fistula formation and persistence represent a host response to bacterial cell wall-derived peptidoglycans. It has been suggested (but with no evidence to confirm this) that cell wall lipopolysaccharides activate proinflammatory cytokine production, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), which could be enhanced by testosterone and inhibited by estrogen, providing an explanation for the lower incidence of anal fistulas in women 44.

Epithelialization of the track has been hypothesized as a cause for persistence of an anal fistula, but it remains uncertain whether this is of primary etiological importance or a secondary phenomenon 20. van Koperen et al. 45 examined 18 fistula tracks and demonstrated epithelialization in 15 patients, mostly around the internal opening. However, this series only included patients with a low fistula undergoing fistulotomy. Mitalas et al. 33 performed a similar study but on 44 patients with a higher fistula involving the external sphincter. Epithelialization of the external part of the track was observed in 11 of 44 (25%) and of the intersphincteric part of the track in 2 of 11 (22%). Thus, epithelialization is uncommon within more complex fistulas.

Another conundrum is the mechanism by which sepsis spreads around the anal canal to form fistulas of differing complexity. Whilst it is easy to envisage infection spreading along paths of least resistance, such as the intersphincteric space or circumferentially in the ischio-rectal fossas, it is more difficult to explain the spread of sepsis through the external sphincter to form a transsphincteric fistula and to provide a logical explanation as to why some fistulas involve little sphincter muscle and others involve most of the external sphincter 20. A plausible explanation is that infection follows fibers of the longitudinal muscle penetrating the external sphincter, but this is by no means proven. Surgical dogma assumes that the ‘deep postanal space’ is critical to the spread of sepsis around the anus, and thus the key to eradicating a fistula was thought to be adequate drainage of this space, as well as control of the primary track. However, what constitutes the ‘deep postanal space’ is disputed, with some going as far as to question whether it exists as a distinct entity 46, 47. Recent radiological and anatomical studies suggest there are several potential, or actual, spaces around the anal sphincters that are likely to be important in the spread of infection. To confuse the issue further, some of these ‘spaces’ cannot be identified in the normal anal canal and only become apparent once sepsis develops and localizes to that area 48, 49.

Anal fistula pathophysiology

An anal fistula, which is an epithelialized connection between the anal canal and external peri-anal area, is characterized by inflammatory tissue and granulation tissue. The distal obstruction prevents the fistula from healing. Because cells are continually being turned over, there is constant debris in the fistula tract, which causes obstruction and prevents healing. The use of a seton and how it allows fistulas to heal is evidence of this as setons allow constant drainage of the fistula and usually result in the fistula migrating and healing.

Anal fistula diagnosis

See a doctor if you have persistent symptoms of an anal fistula. Your doctor will ask about your symptoms and whether you have any bowel conditions. They may also ask to examine your anus and gently insert a finger inside it (rectal examination) to check for signs of a fistula.

If your doctor thinks you might have a fistula, they can refer you to a specialist called a colorectal surgeon for further tests to confirm the diagnosis and determine the most suitable treatment.

Knowing the complete path of an anal fistula is important for effective treatment. The opening of the channel at the skin (external) generally appears as a red, inflamed area that may ooze pus and blood. This external opening is usually easily detected.

Finding the fistula opening in the anus (internal opening) is more complicated. Colorectal surgeons use the latest technology, including the following:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used for mapping the fistula tract and providing detailed images of the sphincter muscle and other structures of the pelvic floor.

- Endoscopic ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to identify the fistula, the sphincter muscles and surrounding tissues.

- Fistulography is an X-ray of the fistula after a contrast solution is injected.

Other options include:

- Fistula probe, an instrument specially designed to be inserted through a fistula

- Anoscope, a small endoscope used to view the anal canal

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy, a procedure to rule out other disorders such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

- An injected dye solution, which may help locate the fistula opening.

Examination under anesthesia

Examination of the perineum, digital rectal examination (DRE), and anoscopy are performed after the anesthesia of choice is administered. This must be done before surgical intervention is initiated, especially if outpatient evaluation causes discomfort or has not helped to delineate the course of the fistulous process.

Several techniques have been described to help locate the course of the fistula and, more important, identify the internal opening. They include the following:

- Inject hydrogen peroxide, milk, or dilute methylene blue into the external opening and watch for egress at the dentate line; in the authors’ experience, methylene blue often obscures the field more than it helps identify the opening

- Traction (pulling or pushing) on the external opening may also cause a dimpling or protrusion of the involved crypt

- Insertion of a blunt-tip crypt probe via the external opening may help to outline the direction of the tract; if it approaches the dentate line within a few millimeters, a direct extension likely existed (care should be taken to not use excessive force and create false passages)

Anal fistula treatment

Anal fistulas usually require surgery as they rarely heal if left untreated. Treatment of anal fistula depends on the fistula’s location and complexity. The goals are to repair the anal fistula completely to prevent recurrence and to protect the sphincter muscles. Damage to these muscles can lead to fecal incontinence.

A range of treatment options include:

- Fistulotomy. The surgeon cuts the fistula’s internal opening, scrapes and flushes out the infected tissue, and then flattens the channel and stitches it in place. To treat a more complicated fistula, the surgeon may need to remove some of the channel. Fistulotomy may be done in two stages if a significant amount of sphincter muscle must be cut or if the entire channel can’t be found.

- Advancement rectal flap. The surgeon creates a flap from the rectal wall before removing the fistula’s internal opening. The flap is then used to cover the repair. This procedure can reduce the amount of sphincter muscle that is cut.

- Seton placement. The surgeon places a silk or latex string (seton) into the fistula to help drain the infection.

- Fibrin glue and collagen plug. The surgeon clears the channel and stitches shut the internal opening. Special glue made from a fibrous protein (fibrin) is then injected through the fistula’s external opening. The anal fistula tract also can be sealed with a plug of collagen protein and then closed.

- Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT). LIFT is a two-stage treatment performed at Mayo Clinic’s campus in Florida for more-complex or deep fistulas. LIFT allows the surgeon to access the fistula between the sphincter muscles and avoid cutting them. A seton is first placed into the fistula tract, forcing it to widen over time. Several weeks later, the surgeon removes infected tissue and closes the internal fistula opening.

In cases of complex fistula, more-invasive procedures may be recommended, including:

- Ostomy and stoma. The surgeon creates a temporary opening in the abdomen to divert waste into a collection bag, to allow the anal area time to heal.

- Muscle flap. In very complex anal fistulas, the channel may be filled with healthy muscle tissue from the thigh, labia or buttock.

Many people do not need to stay in hospital overnight after surgery, although some may need to stay in hospital for a few days.

All the procedures for anal fistulas carries a number of benefits and risks. You can discuss this with the surgeon.

The main risks are:

- infection – this may require a course of antibiotics; severe cases may need to be treated in hospital

- recurrence of the fistula – the fistula can sometimes recur despite surgery

- fecal incontinence – this is a potential risk with most types of anal fistula treatment, although severe incontinence is rare and every effort will be made to prevent it. The word ‘incontinence’ encompasses a wide spectrum, from the odd stain in the underwear, through inadvertent passage of flatus, to frank and devastating loss of stool with the prospect of a colostomy. Incontinence has a negative impact on quality of life 50 but so too does fistula recurrence 51 and an endless cycle of failure and recurrence is to be avoided as fecal incontinence.

The level of risk will depend on things like where your fistula is located and the specific procedure you have. Speak to your surgeon about the potential risks of the procedure they recommend.

Risk factors for fecal incontinence after fistula surgery include a history of anorectal procedures, female gender, complex fistulas, and preoperative incontinence. Fistulotomy should be avoided in fistulas, which are grades 3 or 4 as complex fistulas are associated with higher rates of postoperative incontinence 52. Performing anal manometry can be helpful preoperatively in determining which patients should undergo a sphincter sparing approach as patients that exhibit signs of incontinence before surgery are more likely to have worsened function postoperatively 53. A history of incisions and drainage or multiple fistula surgery is associated with a higher risk of worsened postoperative sphincter function as well as the type of operation performed, a fistulotomy, or a sphincter sparing procedures 54.

Female sex is a risk factor for postoperative incontinence. Treatment of incontinence to flatus and stool involves biofeedback therapy, sacral nerve stimulation. A systematic approach to fecal incontinence has been proposed with initial treatment consisting of bulking agents for stool and increasing dietary fiber followed by training of the pelvic floor muscles with biofeedback therapy. If these are not effective, then more invasive options, including surgical sphincteroplasty, magnetic anal sphincter, or implantation of an artificial anal sphincter may be considered. Only in patients that have exhausted all non-invasive and invasive options is a colostomy offered for recalcitrant fecal incontinence 55.

The best remedy for any complication is prevention. One way to prevent incontinence is by minimizing the number of procedures a patient requires for his or her fistula and tailoring therapy for high-risk patients. Counseling patients preoperatively on the risks of fecal incontinence and obtained preoperative anal manometry are all useful for stratifying patients preoperatively. Obtaining preoperative imaging to classify fistulas before surgery more accurately should be considered as well.

Fistulotomy

A fistulotomy is a procedure that involves cutting open the whole length of the fistula, scraping and flushing out the infected tissue, and then flattening the channel and stitches it in place so it heals into a flat scar. A fistulotomy is the most effective treatment for many anal fistulas, although it’s usually only suitable for fistulas that do not pass through much of the sphincter muscles, as the risk of bowel incontinence is lowest in these cases.

Fistulotomy has an extremely high (95%+) cure rate, as long as all tracks are dealt with 56, 57. As a general rule, fistulotomy results in a reliable cure with good patient satisfaction, where 2 cm of proximal muscle remains intact and in the presence of a ‘normal’ bowel habit, without urgency and in the absence of irritable bowel symptoms 20.

If the surgeon has to cut a small portion of anal sphincter muscle during the procedure, they’ll make every attempt to reduce the risk of bowel incontinence.

In cases where the risk of incontinence is considered too high, another procedure may be recommended instead.

Marsupialization

Marsupialization is the surgical technique of cutting a slit into an abscess or cyst and suturing the edges of the slit to form a continuous surface from the exterior surface to the interior surface of the cyst or abscess. Sutured in this fashion, the site remains open and can drain freely. This technique is used to treat a cyst or abscess when a single draining would not be effective and complete removal of the surrounding structure would not be desirable. Marsupialization after fistulotomy is associated with a significantly shorter healing time and a shorter duration of wound discharge 20. Four randomized trials have demonstrated that marsupialization of the fistulotomy wound reduces time to wound healing 58, 59, 60, 61. Ho et al. 59 demonstrated a faster healing time (6 vs 10 weeks) in 103 patients randomized to fistulotomy vs fistulotomy with marsupialization. A higher squeeze pressure was also seen in the marsupialized group, but the clinical relevance of this is unclear. Pescatori et al. 61 studied 46 patients in the same way and found less bleeding as well as a quicker reduction in wound size in the marsupialized group. More recently, Jain et al. 60 randomized 40 patients to fistulectomy or fistulotomy with marsupialization, demonstrating faster wound healing (around 5 weeks vs around 7) and earlier cessation of wound discharge. Chalya et al. 58 found similar results in 162 patients randomized between the same procedures.

Seton placement

If your fistula passes through a significant portion of anal sphincter muscle, your surgeon may initially recommend inserting a seton. A seton is a piece of surgical thread that’s left in the fistula for several weeks to keep it open. This allows it to drain and helps it heal, while avoiding the need to cut the sphincter muscles.

Essentially a seton can be used in three main ways in the treatment of an anal fistula, with myriad variations of technique between published series. The seton can be inserted and tied loosely over the sphincter to drain the track and allow sepsis to settle before it is removed, in the hope that the fistula will heal (loose seton). The seton can be used to divide the sphincter muscle slowly to eradicate the fistula (cutting seton) and the seton can be used as a long-term drain to provide palliation of symptoms from the fistula, where other techniques are deemed unsuitable.

Loose setons allow fistulas to drain, but do not cure them. To cure a fistula, tighter setons may be used to cut through the fistula slowly. This may require several procedures that the surgeon can discuss with you. Or they may suggest carrying out several fistulotomy procedures, carefully opening up a small section of the fistula each time, or a different treatment.

Loose seton

A loose seton can be used to treat ‘high’ and complex anal fistulas with low risk to diminishing anal control. A loose seton, used as sole treatment, results in fistula healing in only a small proportion of patients. Higher healing rates are achieved by staged fistulotomy after a period of seton drainage.

A number of series of patients treated with a loose seton continue to be reported, often with subtle variation in technique and all highlighting the relative safety of this technique as regards alteration in anal control. However, convincing evidence of fistula healing following simple removal of a loose seton is scant, and often an additional procedure is required to achieve fistula healing. Galis-Rozen et al. 62 reported a series of 77 patients, 17 of whom had Crohn’s disease and were treated with a loose seton alone. Of the 60 patients with non-Crohn’s fistulas, only 4 healed without further surgery and 20 (46%) healed following second-stage fistulotomy. However, a similar proportion of patients either had recurrence or did not heal following seton placement, possibly reflecting the complexity of fistulas included in this series. In a similar manner, Lim et al. 63 described an intriguing modification of the loose seton technique. The primary track was re-routed into the intersphincteric space, by dividing the mucosa and internal sphincter below the internal opening and placing a seton around the external sphincter in the intersphincteric plane, before closing the internal opening, mucosa and divided internal sphincter over the seton. Fifty-three patients were treated by this technique, with a reported recurrence rate of 13% and incontinence reported by two patients. However, follow-up was mostly by telephone contact and no clinical assessment was made to confirm healing of the fistula. An alternative approach was reported by Pinedo et al. 64 in 18 patients with transsphincteric fistulas. The external part of the track was laid open to the outer surface of the external sphincter and an internal sphincterotomy was performed to lay open the intersphincteric element of the track. A loose elastic seton was inserted in the remaining track through the external sphincter and removed when the internal opening had migrated to the anal verge. All setons were eventually removed after a median of 4 months; however, it is not clear how many fistulas healed, although there was deterioration in anal control reported. Subhas et al. 65 used a silk seton as a loose seton, which the patient was instructed to rotate through 360° in each direction on a daily basis. Twenty-four patients were followed for a mean of 45 months (but only by questionnaire and telephone interview), with 18 (75%) fistulas healing, 9 once the seton extruded spontaneously and 9 after low fistulotomy of the residual track: two patients developed incontinence of liquid stool only. Kelly et al. 66 followed a series of 200 patients treated with a polybutylate (Ethibond™) suture, with a recurrence rate of 6% and a low rate of incontinence. However, follow-up was short (6 months) and detail of how changes in anal control were defined and assessed was lacking. Furthermore, although the loose seton controlled symptoms, most patients ended up requiring a second procedure to lay open the residual fistula track. Follow-up is not described in any detail and four patients (6%) were said to have experienced ‘minor’ incontinence.

Tight seton (cutting seton)

A tight seton can be used to treat selected ‘high’ and complex anal fistulas where other techniques are either not suitable or have failed. The patient should be counselled carefully as to the risk of permanent incontinence. A tight seton inserted into a transsphincteric fistula will result in healing in upwards of 90% of patients. There is some risk of diminishing anal control that is influenced by the height of the internal opening and the amount of muscle encompassed in the seton.

A tight seton has been used where a surgeon is unwilling to perform fistulotomy because it is thought that too much sphincter will be divided in the process and the risk of incontinence is high. A variety of techniques have been described, all with the same principle, namely slow division of the sphincter encompassed by the seton, with progressive caudal migration of the track and eventual extrusion of the seton. Much is made of the theory that this slow division with a foreign material generates fibrosis around the sphincter as it is divided, limiting separation of the sphincter ends and healing of the muscle cephalad to the seton as it descends the anal canal. This is in contrast to the springing open of the sphincter ends that occurs with primary fistulotomy. Attractive as this theory sounds, there is little or no evidence to substantiate improved sphincter morphology and function over immediate fistulotomy. Anecdotal comparison of ultrasound appearances of the sphincters after cutting seton suggest less sphincter separation than after fistulotomy, but it is uncertain if like is being compared with like 67. Rosen and Kaiser 68 used data from Ritchie et al. 69 to demonstrate an association between the rate of incontinence and the interval between seton tightening, which they interpreted as supporting evidence that slow sphincter division preserves sphincter function. However, this requires a large leap of faith, as the data used were very heterogeneous, with different definitions of incontinence and periods of follow-up.

Evidence in favor of the use of a cutting seton is still based on case series, and no specific randomized trial of tight setons vs other surgical options has been performed. Most studies suffer from a number of flaws, usually involving the definition of end-points, limited follow-up and low numbers. A variety of different materials have been used as tight setons, including silk 70, rubber bands, rubber surgical glove 71, silastic vessel sloop 72 and electrical cable tie 73. Each modification is designed to make tightening the seton simple as well as avoiding the need for a general anaesthetic. Similarly, some authors perform internal sphincterotomy prior to seton insertion 74 and others encompass both the external and internal sphincters in the seton, after removing skin and anoderm beneath the seton 67. Whichever technique is employed, the internal sphincter will eventually be divided by the seton as it cuts through the fistula track and overlying sphincter. Vial et al. 75 performed a meta-analysis on a number of case series looking at recurrence rates and alteration in anal control after use of a cutting seton, with and without sphincterotomy at time of seton insertion. They concluded that recurrence rates were similar (at less than 5%), but overall incontinence was higher after sphincterotomy (25%) than after seton insertion without sphincterotomy (6%). However, these results should be interpreted with considerable caution as the studies were very heterogeneous, with different follow-up periods and different methods of assessing changes to incontinence.

Raslan et al. 70 collated 51 patients treated with a tight silk seton, with a recurrence rate of 10% and incontinence to flatus of 16% and liquid stool of 6%. However, details as to the anatomy of the fistulas treated and how continence was assessed are absent and follow-up duration was not specified, but was likely to have been short. A similar study by Kamrava et al. 76 used silk, but tightening of the seton was controlled by the patient. Recurrence was 10% and only 1 of 47 patients was reported to have new problems with control, although definitions used for assessing control were loose and follow-up was short. Using a thin electrical cable tie as a seton is intriguing: Memon et al. 73 reported a series of 79 patients with transsphincteric or suprasphincteric fistulas, with a recurrence rate of 5% and no reported change in continence. However, no details were given as to the level of discomfort experienced by the patients, who required on average six tightenings of the seton and an average of 12 weeks for healing to occur. Hammond et al. 72 used a silastic vessel and nerve sloop as a ‘snug’ seton in a series of 29 patients. The seton cut through the enclosed tissue in 15 patients, but 14 patients required a superficial fistulotomy to finally remove the seton. There were no recurrences identified, and 10 patients (34%) experienced early minor incontinence, which persisted in 4 of 16 patients followed for a median of 42 months. Leventoglu et al. 71 used a rubber glove as a ‘hybrid’ seton; this was not tied as tightly as a traditional cutting seton with the same intention as Hammond et al. 72. Side tracks were dealt with by a modified Hanley technique, using Penrose drains. With this technique there was one recurrence over a mean follow-up of 20 months and no significant change in the Cleveland continence score. Ege et al. 67 used the cuff from a rubber glove as a ‘hybrid’ seton, tied snugly over the denuded external sphincter following internal sphincterotomy. They followed 128 patients, with the seton extruding after a mean of 19 days, suggesting that many fistulas were low. Complete healing occurred at 3 months in all patients and only two patients returned with a recurrent fistula after a minimum of 12 months’ follow-up. However, in common with other studies, it is unclear as to how tightly the seton was tied over the sphincter. Izadpanah et al. 74 described a technique they called a ‘pulling seton’ in a large series of 201 patients in whom they divided the internal sphincter and the external part of the fistula, before tying a seton over the remaining external sphincter muscle. The patient was instructed to tug on the seton four times a day. Using this technique, they reported a recurrence rate of 5% and no permanent gas or faecal incontinence. However, follow-up was short and postoperative assessment of continence was limited. Rosen and Kaiser 68 reported on 121 patients with a transsphincteric fistula treated by tight seton. Initial healing occurred in 90% of patients, rising to 98% after further surgical procedures. Interestingly, 17 patients with preexisting continence problems improved following surgery, indicating that the presence of a fistula can cause continence problems (possibly by discharge through the track). Only eight patients developed new problems with anal control. These excellent results should be interpreted with some caution as follow-up of these patients was short (mean 5 months).

In summary, a variety of materials have been used as a cutting seton, with most series reporting successful healing of the fistula and recurrence rates of the order of 10% after short-term follow-up. It is uncertain if internal sphincterotomy is a necessary part of the procedure. It is likely that sphincter division (even slow division) will inevitably lead to some diminution in anal control, which may not become apparent immediately. Ritchie et al. 69 collated a large number of series and calculated an average incontinence rate of the order of 12%.

Advancement flap procedure

An advancement flap procedure may be considered if your fistula passes through the anal sphincter muscles and having a fistulotomy carries a high risk of causing bowel incontinence. An advancement flap may also be used to close an anorectal or recto-urethral fistula.

Advancement flap surgery involves cutting or scraping out the fistula and covering the hole where it entered the bowel with a flap of tissue taken from inside the rectum, which is the final part of the bowel.

An advancement flap procedure has a lower success rate than a fistulotomy, but avoids the need to cut the anal sphincter muscles.

Adequate vascularity of the flap and tension-free anastomosis, placed well beyond the site of the (excised) internal opening, are key to success. Advancement flaps can be taken from the rectum (transanal advancement flap) or from the perianal skin (cutaneous advancement flap). Also described are the transanal sleeve advancement flap (TSAF) and the Delorme’s-style advancement flap. This is similar to the transanal sleeve advancement flap (TSAF) but, as in the Delorme’s procedure for rectal prolapse, after mucosal mobilization the muscle wall is advanced and sutured down to the internal anal sphincter distal to the internal opening of the fistula. This procedure is facilitated by internal intussusception and would not be a tension-free repair without it 77. The presence of internal intussusception or perineal descent may facilitate advancement flap repair.

A number of factors have been identified as risk factors for failure of an advancement flap procedure. These include, smoking 78, a flap for a recurrent fistula 79, Crohn’s disease 80, horseshoe abscess 81 and high BMI 82. Differing study populations may explain heterogeneity in the significance of risk factors identified in different studies.

Advancement flap procedures are safe. Early case series suggested efficacy in around 70% of patients 20. However, more recent randomized controlled trial data, often vs the anal fistula plug, and larger series, suggest healing in a smaller proportion, perhaps of the order of 50–60% 83, 84. A recent multicentre randomized trial of 94 patients from Scandinavia found a primary success rate (defined as clinical healing), at a median of 12 months of follow-up, of 62% of 40 patients 85. A full-thickness flap was used and patients had a single, non-complex high transsphincteric track and after only a single previous fistula operation (probably seton insertion). The comparator group, treated with a fistula plug, achieved clinical success in only a third of patients. MRI confirmation of healing was not reported in either arm 85. This study represents a robustly performed assessment of transanal rectal advancement flap surgery in well-selected patients, and is a realistic report of the technique 85. A recent meta-analysis including 26 studies and 1655 patients indicated an increasing success rate (avoidance of recurrence) with increasing thickness of the flap raised, although there was significant heterogeneity between studies 86. The pooled recurrence rate was 21%, but ranged from 0% to 47%. Core out vs curettage of the track did not influence outcome.

There is great heterogeneity in how continence is assessed following advancement flap surgery. Early studies found little impairment of continence but some authors suggest minor incontinence may occur in around a quarter of patients 87. Meta-analysis suggests a greater likelihood of continence impairment with full-thickness flaps (20%) than mucosal or partial thickness flaps (10%), although the impairment was generally minor 86.

Transanal advancement flap

Transanal advancement flap can be used to treat an anal fistula where simple fistulotomy is thought likely to result in unacceptable impairment of continence. The success rate of transanal advancement flap is of the order of 60%.

The transanal rectal advancement flap procedure has several advantages over other treatments for anal fistula. Division of the external sphincter is avoided with less risk of impairment of continence, and defects of the contour of the anal canal, such as a keyhole deformity, are avoided and healing is quicker than after fistulotomy. Additional procedures can be incorporated into the operation, such as sphincteroplasty, without the need for a protective colostomy. Failure of the repair does not usually lead to worse symptoms, although the internal sphincter at the level of the anorectal junction will have been disrupted to a certain extent and the anal canal will be somewhat more rigid as a result of scar tissue. This could result in functional impairment.

Relative contraindications to the transanal rectal advancement flap procedure include: the presence of proctitis – especially in patients with Crohn’s disease; undrained sepsis and⁄or persisting secondary tracks; an anorectal fistula with a diameter > 3 cm; malignant or radiation-related fistula; a fistula of less than 4 weeks’ duration; and an associated stricture of the anorectum 88. Stricture, tissue loss and scarring of the anorectum may impair the surgeon’s access and may make flap repair technically impossible.

The surgical technique for endoanal advancement flap procedures has been described in earlier publications 89, 90, 91. Whilst many surgeons would use mechanical bowel preparation prior to surgery, and consider the use of a defunctioning stoma to cover the procedure, there is no evidence base to support these approaches. A semi-circular flap is most commonly used as this avoids ischemia at the corners. The majority of authors describe a U-shaped flap, while a minority use an inverted U-shaped flap. The flap consists of mucosa, submucosa and a varying degree of circular muscle from none to the full rectal wall thickness, depending on the author. There has been limited evidence from individual studies to support the logical assertion that more muscle means greater vascularity and therefore success, at the cost of a greater risk of impairment of continence, but pooled data from a recent meta-analysis suggest that this is correct 86.

Transanal sleeve advancement flap (TSAF)

The transanal sleeve advancement flap (TSAF) procedure takes the concept of flap advancement one step further by mobilizing the circumference of the anal canal. It has been used for a subgroup of patients with severe complex fistulas associated with Crohn’s disease 92. The technique is similar to the transanal flap procedure described above, but in addition a 90–100% circumferential incision is made at or just below the dentate line to create a sleeve of the full thickness of the bowel wall. This is then mobilized proximally into the supralevator space until sufficient mobility is achieved to allow the flap to be advanced distally into the anal canal without tension. Its distal edge is then sutured with absorbable sutures to the epithelium of the anal canal below the level of the internal opening. This technique may offer an alternative in selected patients with fistulation in Crohn’s disease without proctitis, for whom the only alternative is proctectomy with permanent stoma.

The cutaneous advancement flap procedure

The cutaneous advancement flap procedure is an alternative to rectal advancement flap repair of a high fistula. The cutaneous advancement flap procedure has a similar success rate to endoanal flap, but the theoretical risk of avoiding ectropion formation.

The cutaneous advancement flap appears to have a similar success rate to endoanal flap procedures, with the theoretical advantage that by moving skin into the anal canal, mucosal ectropion is avoided 93, 94. The technique for the procedure has been described elsewhere 93, 94.

Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure

The ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure is a treatment for fistulas that pass through the anal sphincter muscles, where a fistulotomy would be too risky. During the treatment, a cut is made in the skin above the fistula and the sphincter muscles are moved apart. The fistula is then sealed at both ends and cut open so it lies flat.

This procedure has had some promising results so far, but it’s only been around since 2007 95, so more research is needed to determine how well it works in the short and long term.

Three randomized controlled trials have been reported ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure 96, 97, 98. One only compared LIFT with a modification of LIFT, rather than a standard treatment, whilst the other two compared LIFT with a mucosal advancement flap. In addition, 18 case series have been reviewed 20.

Madbouly et al. 98 randomized 70 patients to either LIFT or a mucosal advancement flap. Primary healing was achieved in 33 (94%) patients undergoing LIFT compared with 32 (91%) patients undergoing a flap repair. Median healing times were 22.6 and 32.1 days, respectively. After follow-up of 1 year, a successful outcome was achieved in 26 (74%) of the LIFT group compared with 20 (66%) in the advancement flap group, highlighting the importance of long-term follow up in fistula surgery research. There was no significant difference in continence scores in this study.

A similar, but smaller, study randomized 25 patients to LIFT and 14 to anorectal advancement flap 96. All patients had seton inserted prior to definitive surgery. Recurrences were seen in 2/25 and 1/14, respectively. The authors concluded that LIFT was simple and safe, took significantly less time than a flap and patients returned to work earlier.

Sileri et al. 99 reported 26 patients with complex fistulas, 19 of whom were healed at a minimum of 16 months following LIFT. The recurrences occurred between 4 and 8 weeks following surgery. They defined ‘complex’ as any track that was deeper than 30% of the external sphincter, anterior fistula in women, recurrent fistula or preexisting incontinence. Only two patients had previously had a loose seton inserted prior to the LIFT procedure. Another series of 40 patients with transsphincteric fistulas deemed to be inappropriate for fistulotomy underwent LIFT 100. Success rates of up to 74% were noted, although follow-up was short (a mean of 18 weeks).

Ooi et al. 101 reported 25 patients who had undergone LIFT. Ten of them had developed recurrence after previous fistula surgery. The primary and secondary end-points were cure rate and degree of incontinence, respectively. Primary healing was observed in 17 (68%) patients at a median of 6 weeks. Seven patients had recurrence of their fistula, which presented between 7 and 20 weeks’ postoperatively. There was no reported incontinence. Liu et al. 102 recruited 38 patients between 2008 and 2011. At a median follow-up of 26 months (26 patients had at least 12 months’ follow-up), healing was seen in 23/38 (61%). One failure occurred over 12 months after the index procedure, with 80% of failures occurring within the first 6 months following the procedure. No intra-operative complications or incontinence were noted. Increasing fistula length was associated with decreased likelihood of healing.

A recent large series (167 patients) reported a success rate (healing) of 94% at a median follow-up of 12 months 103. The majority of fistulas were transsphincteric 104 and a number were recurrent 105. Ten patients who developed a recurrent fistula were managed with a repeat LIFT procedure. Schulze et al. 106 performed LIFT on 75 patients between May 2008 and June 2013. All had undergone an initial procedure that involved drainage of sepsis, insertion of a loose seton and partial fistulotomy. There were nine recurrences, at a mean follow-up of 14.6 months, all of which were treated with repeat LIFT and biograft or anorectal advancement flap. There were no subsequent recurrences. Recurrences were related to fistulas with multiple tracks. Only one patient reported a change in continence.

An attempt has been made to determine whether LIFT is more effective in distinct fistula sub-types 107. LIFT was performed in simple transsphincteric (five), complex fistulae (six) and recurrent cases postfistulotomy (six). The overall success rate at a mean follow-up of 11 months was 53%. Healing rates in the three groups were four out of five, three out of six and two out of six, respectively. These numbers are too small to draw any conclusions, but intuitively LIFT should be more likely to succeed in less complicated fistulas (as is the case for all fistula treatments). There is general consensus that the presence of multiple tracks, diabetes mellitus, perianal collections and long tracks are all associated with a higher chance of failure of LIFT.

LIFT has been employed as an alternative to fistulotomy in patients with low transsphincteric fistulas 108. Healing was seen in 18/22 patients recruited at a median follow-up of 19.5 months. The four unsuccessful cases were treated with fistulotomy. Although there was no comparison with patients with similar fistulas undergoing fistulotomy as sole treatment, the authors reported a final healing rate of 100% and no alteration in continence, which was assessed prospectively.

A Chinese group recently reported on 43 patients with ‘complex’ fistulas treated by LIFT, all of whom were followed up for more than 1 year 109. Healing of the fistula was seen in 36 of 43 (84%) patients; failure, when seen, occurred a mean of 8.6 weeks after the original procedure. In this series, eight patients had dehiscence or infection at the site of the intersphincteric wound, with five patients requiring laying open. This complication is probably commoner than reported in many series.

Modifications to the LIFT procedure have been described. The Bio-LIFT procedure, for example, involves placing a biograft (usually a piece of collagen mesh) in the intersphincteric space following ligation of the intersphincteric fistula track. Success was reported in 11 of 16 (63%) fistulas treated, at a median follow-up of 26 weeks 110. A randomized trial comparing the two approaches in 235 patients reported healing rates at 6 months of 94% in the LIFT + biograft group, vs 84% in the LIFT group alone 97. The authors reported that the addition of the graft had the advantage of higher healing rates, decreased healing time and a lower early postoperative pain score. Another modification involves making a lateral incision from the external opening to the intersphincteric groove, ligating the fistula track within the intersphincteric space and complete excision of the external part of the fistula 111. In a series of 39 patients treated in this way and followed for a mean of 15 months, 34 (87%) achieved healing. There was no change in continence, as measured by the Cleveland Clinic score preoperatively and at 6 months postoperatively. An alternative approach is to de-roof the fistula from internal opening to intersphincteric groove and ligate the fistula track, while at the same time preserving the external sphincter. This modified LIFT was performed on a series 56 patients, with an overall cure rate of 71%. True recurrence (5%) was much less frequent than simple failure of the technique and persistence of an active fistula track after the operation 112.

LIFT has been used as treatment for recurrent fistulas 113. Fifteen patients with recurrent transsphincteric fistulas were followed up for 8–26 months (median 13.5 months). At the end of follow-up, six patients still had evidence of fistula, either persistence of the original fistula (four patients) or recurrence (two patients). LIFT has also been used in selected patients with Crohn’s disease, with 8 of 12 reported to be healed at 12 months 114.

To conclude, to date there are a few randomized studies as well as number of case series that attest to the potential efficacy of LIFT. LIFT appears to be associated with less functional compromise than some traditional treatments of transsphincteric fistulas, although recurrence/persistence rates are probably similar. One of the advantages of the LIFT procedure is that of secondary success. Where a genuine downstaging of the fistula from transsphincteric to intersphincteric takes place in a proportion of failures, allowing laying open of this intersphincteric fistula, preserving the external sphincter which would have been involved originally 115. Future work should focus on comparison with standard treatments, paying particular attention to comparing similar fistulas and focusing on deeper fistulas, where conventional treatments may be more problematic as regards functional outcome.

Fibrin glue

Treatment with fibrin glue is currently the only non-surgical option for anal fistulas. It involves the surgeon injecting a glue into the fistula while you’re under a general anesthetic. The glue helps seal the fistula and encourages it to heal.

It remains uncertain as to which fistulas are suitable for fibrin glue treatment. Success (fistula healing) is low when the fistula track is short. Treatment with fibrin glue is generally less effective than fistulotomy for simple fistulas and the results may not be long-lasting, but it may be a useful option for fistulas that pass through the anal sphincter muscles because they do not need to be cut.

With variable and mostly low rates of healing, fibrin glue is not recommended for routine use in anal fistulas, but may be considered where other surgical options are not feasible 20.

Various autologous and commercial preparations of fibrin glue have been used to treat anal fistulas. Autologous glues are formed from the patient’s own blood, whilst commercially available glues are a mixture of clotting factors, aprotinin and calcium (Beriplast; CSL Behring, Pennsylvania, USA; Tisseel; Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, Illinois, USA), or are synthetic glues, such as cyanoacrylate (Glubran; GEM SRL, Viareggio, Italy). The glues are applied to fill the fistula track and provide a bridge for fibroblasts and stromo-vascular cell in-growth to produce healing. Their ease of use, minimal risk to continence and repeatability make them an attractive option, especially in patients at high risk of sphincter dysfunction 104, 116.

A wide range of healing rates with fibrin glues have been reported, ranging from 14% to 94% 117, 118. Variability in disease complexity, fistula anatomy and surgical technique makes comparison of the results from randomized trials difficult to interpret 119. A meta-analysis has not shown any statistical difference with the use of fibrin glue, compared to other conventional surgical treatments, in terms of fistula recurrence or incontinence 120.

Some authors have reported better healing rates in longer tracks, suggesting that shorter tracks (< 3.5 cm) are less likely to retain the glue 121, but this has been contradicted in other reports 122, 123. Technical errors have been suggested for failure, including inadequate curettage and washout to remove all infected and epithelialized tissue 155, 161, 162, or incomplete filling of the track with the glue to ensure occlusion 121.

Like other fistula treatments, recurrence rates with fibrin glue increase with the length of follow-up. A long-term follow-up study showed that up to 26% of patients who were symptom free at 6 months went on to develop recurrence at an average of 4.1 years 124. However, on several occasions the recurrence was at a different site, suggesting that a new fistula had formed. The highest probability of failure appears to occur in the first 6 months following treatment, so 6 months should be the minimum follow up period 125.

A multicentre trial randomized patients to fibrin glue or seton treatment for transsphincteric fistulas and showed a 38% healing rate in the fibrin glue group, compared with 87% in the seton group 104. Patients who had a recurrence after fibrin glue were further randomized to repeat glue treatment or a loose seton. A further 50% healed with repeat glue treatment. Notably, there was a significant worsening in the Cleveland Clinic continence score in the seton group. Many studies have investigated the use of repeat glue application to increase healing rates, even up to four applications 126. A prospective study of fibrin glue for simple transsphincteric and intersphincteric fistulas showed that repeat glue treatment decreased the overall recurrence rate from 23% to 7.6% 127. Conversely, other authors have reported that repeated applications of fibrin glue are unlikely to succeed 128 and other studies have shown an adverse outcome when fibrin glue is combined with an endorectal advancement flap 129.

Various strategies have been suggested to improve the healing rates with glues. Local sepsis should be eradicated with the use of preoperative setons, the track should be thoroughly curetted and the track irrigated with either saline or hydrogen peroxide. Preoperative bowel preparation has not consistently shown a benefit. Suturing the internal or external openings shut has been advocated, but not shown to confer a significant benefit 117.

It has been suggested that high failure rates with the glue may be a consequence of the glue not being retained in the fistula track 130. To overcome this, some authors have recommended the use of stool softeners and avoiding straining and exercise in the postoperative period, although there are no data to support this. Other explanations for failure of fibrin glue include early resorption/degradation within 5–10 days of application, providing insufficient time for established healing 131, 132. A Phase 1 trial using Permacol® glue, which incorporates fibres suspended in fibrin glue to provide a physical scaffold for host cell proliferation after glue absorption, has shown promising results, but more, randomized, data are required 132. Newer autologous fibrin sealants have not shown any increased efficacy compared with conventional glues, with healing rates of up to 40% 133. Research continues into the use of stem cell autologous suspensions for fistula application and the ADMIRE CD study used fibrin glue as the scaffold for allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell treatment of Crohn’s anal fistulas 134. This may represent the main role for fibrin glue in the future.

Bioprosthetic plug

Another option is the insertion of a bioprosthetic plug. This is a cone-shaped plug made from animal tissue that’s used to block the internal opening of the fistula and preventing fecal material from entering. Anal fistula plugs procedure works well for blocking an anal fistula and there are no serious concerns about its safety. Anal fistula plugs provide a physical scaffold for in-growth of host regenerative and immune cells to promote healing and repair. The plugs degrade over a period of several weeks, by which time the repair process is established.

Accepting that rates of healing are variable, an anal fistula plug is an option for treating transsphincteric fistulas, especially where surgical options are considered to have a significant risk of jeopardizing continence. The additional cost of the plug should be taken into account when considering this surgical treatment. The initial reported high success rates of anal fistula plugs have not been maintained in later series, but, similar to fibrin glue, anal fistula plugs do not threaten continence. It remains uncertain as to which fistulas are best suited to fistula plug treatment.

Types of bioprosthetic plug

Several fistula plugs have been developed commercially, but the BioDesign Surgisis® Anal Fistula Plug (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, USA), composed of acellular, lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa, is the most established 20. Other plugs include the GORE Bio A® Fistula Plug (Flagstaff, Arizona, USA), a composite of polyglycolic acid and trimethylenecarbonate synthetic polymers 174, which has now been withdrawn by the manufacturer, the Pressfit® plug (Deco Med s.r.l., Venice, Italy), which is made from acellular dermal matrix, and the Curaseal AF® device (CuraSeal, Inc., Santa Clara, California, USA), which incorporates a silicone disc to reinforce occlusion of the internal fistula opening. Secure anchoring of the plug at the internal opening is a critical feature in the design of all these plugs.

Reported success rates for fistula healing with anal fistula plugs vary, ranging from 24% to 88% 175, reflecting differences in patient selection, plugs used, surgical technique, definition of healing and length of follow-up. In 2007, a Consensus Conference was held to establish uniformity in the indications and techniques for insertion of the Cook Medical fistula plug 135. It concluded that all types of ano-cutaneous fistula were suitable for plug treatment, with transsphincteric fistulas being the ideal indication. Emphasis was placed on the prior control of associated sepsis and the use of seton drainage for 6–12 weeks preoperatively. Debridement or curettage of the track was discouraged, although gentle brushing to de-epithelialize the track was subsequently recommended, with saline or hydrogen peroxide irrigation being optional. Secure suturing of the plug to the internal opening/internal sphincter was considered important to prevent early extrusion of the plug, which had been reported as a cause for failure in some studies 136. There was no evidence to support the routine use of a rectal mucosal flap to cover the plug. Suturing of the plug has been facilitated by modification of the original plug design to incorporate an internal ‘button’.

Initial encouraging results from Johnson et al. 137 reporting closure rates of up to 87% have not been reproduced in later studies, which have presented mixed results. A randomized trial comparing the fistula plug with endorectal advancement flap (ERAF) was closed prematurely due to a high incidence of recurrence in the plug arm 138. In another randomized controlled trial, comparing an acellular dermal matrix (ADM) plug vs fistula plug with endorectal advancement flap (ERAF), a healing rate of 82% was reported in the ADM group, with lower rates of recurrence (ADM plug 4% vs ERAF 28%) 139. A subsequent meta-analysis comparing the plug with endorectal advancement flap (ERAF) failed to show any difference in recurrence rates or complications 140. However, a recent robust multicentre randomized controlled trial of 94 patients with a transsphincteric fistula demonstrated clinical healing at 12 months in only 38% (15 of 44 patients) treated by collagen plug, compared with 66% (27 of 41 patients) treated by endorectal advancement flap (ERAF) 85.

A potential disadvantage with the plug is the cost of the device, but this may be offset by a shorter hospital stay. In a study comparing fistula plug against endorectal advancement flap (ERAF), healing rates were similar, but the costs associated with endorectal advancement flap (ERAF) were higher due to a longer duration of hospital stay 141.

In a recent UK multicentre study (the NIHR FIAT trial) 152 patients were randomized to receive the Cook Biodesign fistula plug and compared with 152 patients receiving surgeon’s preference [cutting seton, ERAF, fistulotomy or ligation of intersphincteric fistula track (LIFT)] 142. Similar clinical fistula healing rates were observed at 12 months’ follow-up (plug 54% vs surgeon’s preference 57%) 142. Early plug extrusion remained a problem, despite the adoption of best surgical technique, occurring in 15% of cases. Rates of incontinence were low in both groups and there was no statistical difference in quality of life as measured by the Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQoL) and EQ-5D scoring systems. Complications rates were similar between the two groups, with the exception of increased early postoperative pain in the plug group, presumably associated with suturing to the internal anal sphincter.

The fistula plug has been successfully used in combination with other procedures, including the LIFT procedure. In a large, multicentre RCT, the LIFT–plug procedure was found to result in statistically significant higher healing rates compared with LIFT alone (LIFT–plug 94.0% vs LIFT 83.9%) 97.

Most studies have included variable follow-up after surgery, ranging from 3 to 12 months. A long-term follow-up study, using MRI to assess fistula healing at 12 months after plug insertion, showed radiological evidence of a persistent fistula in up to 21% of patients, suggesting that reports of fistula healing at 12 months are likely to be an overestimate 143.

Benefits in favor of the fistula plug include ease of use and lack of complications. No differences in complication rates have been reported between ERAF and AFP 140, with documented complications including sepsis/abscess, recurrence and constipation 97. Unlike some other techniques, no study has reported a detrimental effect to continence following use of a plug. Thus, the fistula plug is an option for treating a transsphincteric fistula. Uncertainty in healing efficacy is counterweighed by the lack of detrimental effect on continence. The cost of the device might be offset by shorter lengths of hospital stay.

Endoscopic ablation

In this procedure, an endoscope (a tube with a camera on the end) is put in the fistula. An electrode is then passed through the endoscope and used to seal the fistula.

Endoscopic ablation works well and there are no serious concerns about its safety.

Laser surgery

Radially emitting laser fiber treatment involves using a small laser beam to seal the fistula. There are uncertainties around how well it works, but there are no major safety concerns.