What is angina

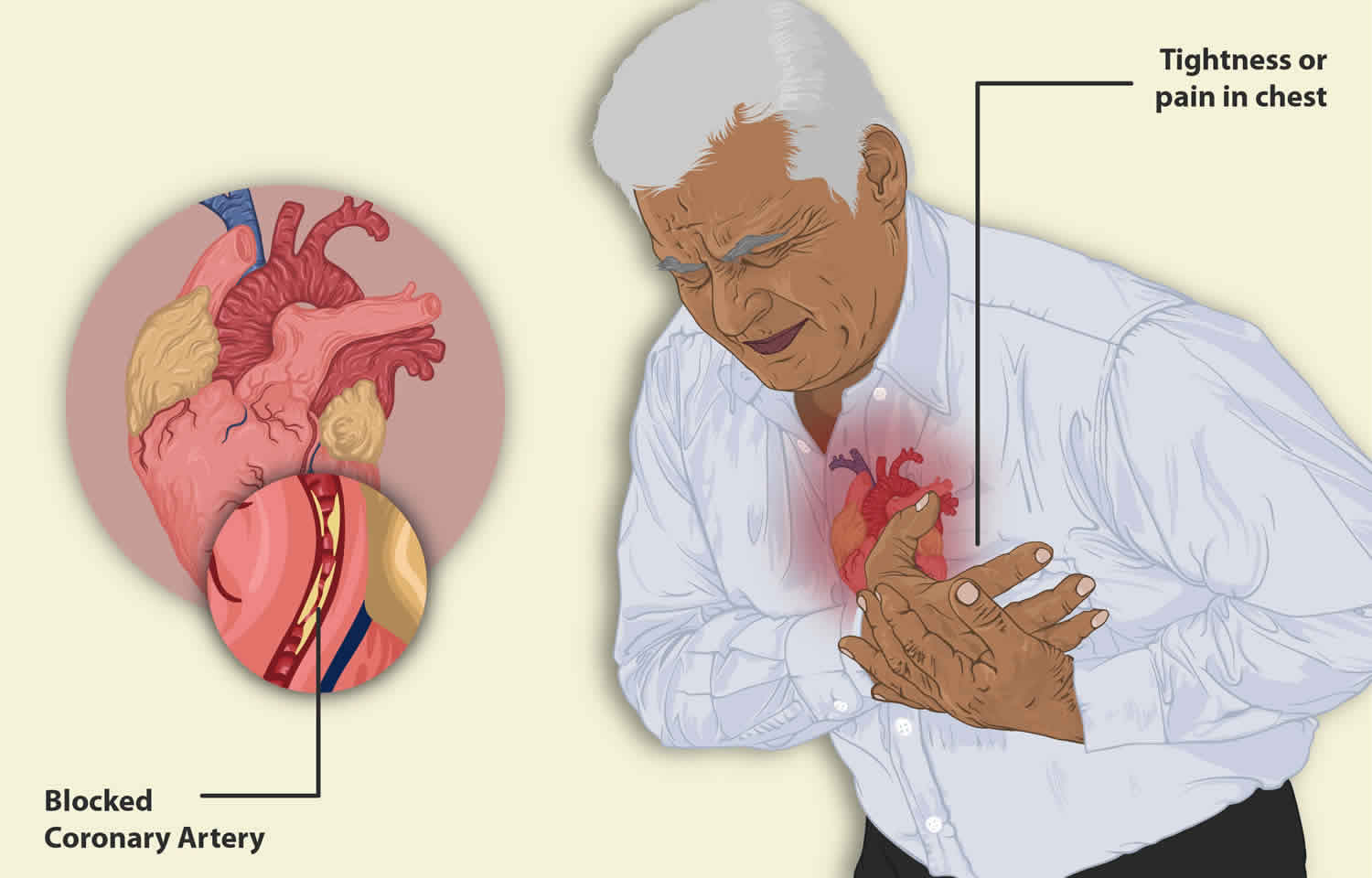

Angina is also called angina pectoris, is a heart condition that causes chest pain, pressure or discomfort you feel when there is not enough blood flowing to your heart muscle. You may also feel the discomfort in your neck, jaw, shoulder, back, arms or stomach. People sometimes describe the feeling as a dull ache. Angina symptoms are not the same for everyone. Some people may feel the pain or tightness only in their arm, neck, stomach or jaw. For some people the chest pain or tightness is severe, while others may feel nothing more than a mild discomfort or pressure. Angina usually happens during activities like walking, climbing stairs, exercising, or cleaning or when someone is upset. Angina can be a symptom of coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease). This occurs when the coronary arteries that carry blood to your heart become narrowed and blocked because of atherosclerosis (thickening or hardening of the arteries caused by a buildup of plaque, which are made up of deposits of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin) or a blood clot. Angina pectoris can also occur because of unstable plaques, poor blood flow through a narrowed heart valve, a decreased pumping function of the heart muscle, as well as a coronary artery spasm. The amount of pain or discomfort you feel does not always reflect how badly your coronary arteries are affected. Angina goes away after a few minutes. However, you should go to the emergency room if you have chest pain that won’t go away. If your chest pain lasts longer than 5 minutes, call your local emergency services number and ask for an ambulance.

Angina symptoms may include:

- Chest pain, dull ache or discomfort often described as squeezing, pressure or tightness

- Intense sweating

- Difficulty catching your breath or shortness of breath

- Pain in your arms, neck, jaw, shoulder or back, even if you don’t have pain in the chest

- Nausea

- Fatigue (feeling overly tired)

- Dizziness

- The feeling of gas or indigestion

- Pain that comes and goes

If you have any of these symptoms, see your doctor. Although angina is relatively common, it can still be hard to distinguish from other types of chest pain, such as the discomfort of indigestion or muscular pain. If you have unexplained chest pain, it’s very important you seek medical help right away, so that your doctor can assess you to find out why you are getting the pain.

- If you have any symptoms of angina, immediately stop, sit down and rest. If your symptoms are still there once you’ve stopped, take your usual angina medication, if you have some.

- If the symptoms are still there in 5 minutes, repeat the dose. Tell someone how you’re feeling, whether that’s by phone or simply the nearest person.

- If the symptoms are getting worse, or are still there in 5 more minutes, call your local emergency services number and ask for an ambulance.

- Chew an adult aspirin tablet (300mg) if there is one easily available, unless you’re allergic to aspirin or have been told not to take it. If you don’t have an aspirin next to you, or if you don’t know if you’re allergic to aspirin, just stay resting until the ambulance arrives.

The chest pain that occurs with angina can make doing some activities, such as walking, uncomfortable. However, the most dangerous angina complication is a heart attack. A heart attack is when a part of the heart muscle suddenly loses its blood supply. This is usually due to coronary heart disease.

Warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Pressure, fullness or a squeezing pain in the center of the chest that lasts for more than a few minutes

- Pain extending beyond the chest to the shoulder, arm, back, or even to the teeth and jaw

- Fainting

- Impending sense of doom

- Increasing episodes of chest pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Continued pain in the upper belly area (abdomen)

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

If you have any of these symptoms, seek emergency medical attention immediately.

To diagnose angina, your doctor will ask you about your signs and symptoms and may run blood tests, take an X-ray, or order tests, such as an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG), an exercise stress test, or cardiac catheterization, to determine how well your heart is working.

With some types of angina, you may need emergency medical treatment to try to prevent a heart attack. To control your condition, your doctor may recommend heart-healthy lifestyle changes, medicines (glyceryl trinitrate or GTN), medical procedures, and cardiac rehabilitation.

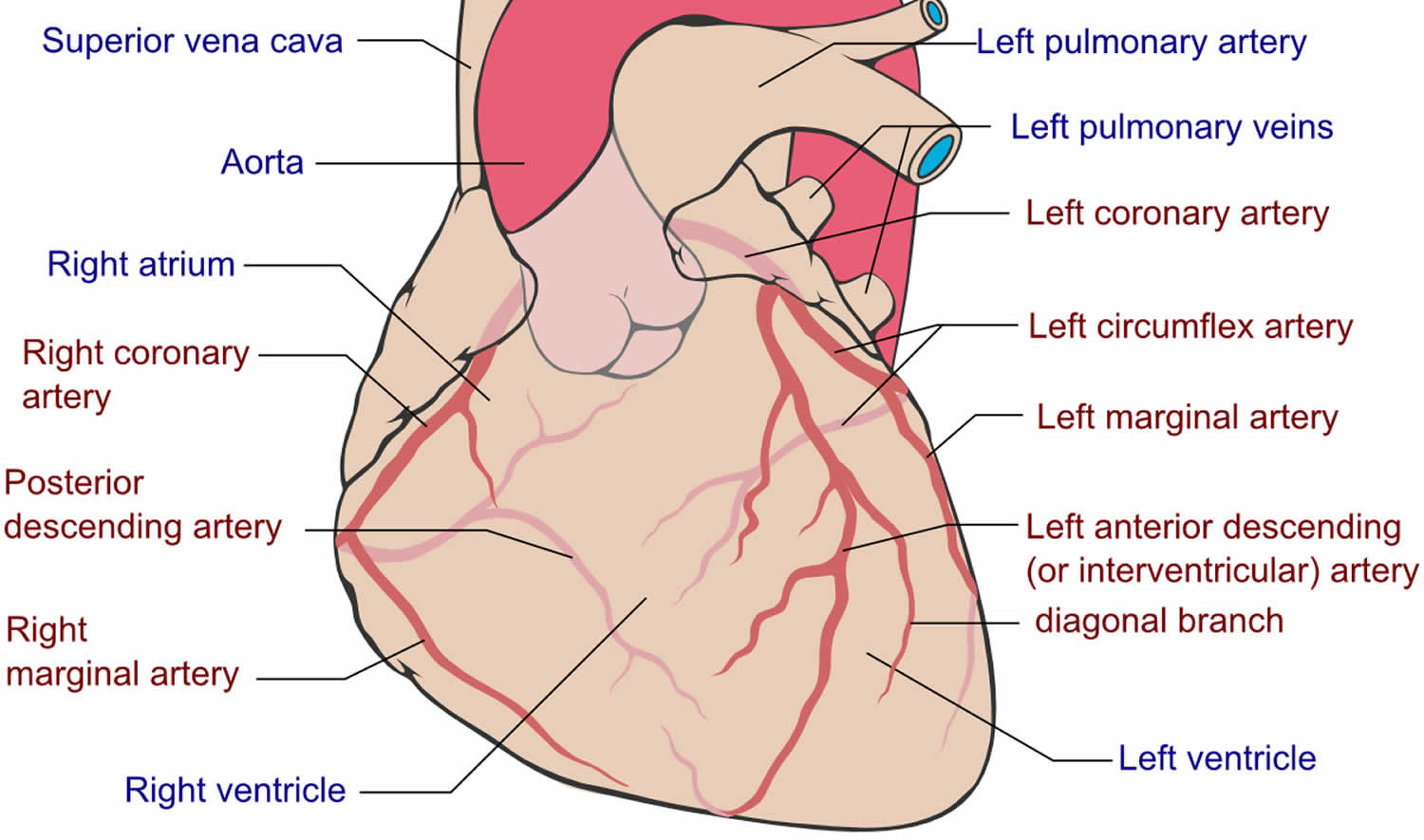

Figure 1. Coronary arteries supplying blood, oxygen & nutrients to your heart

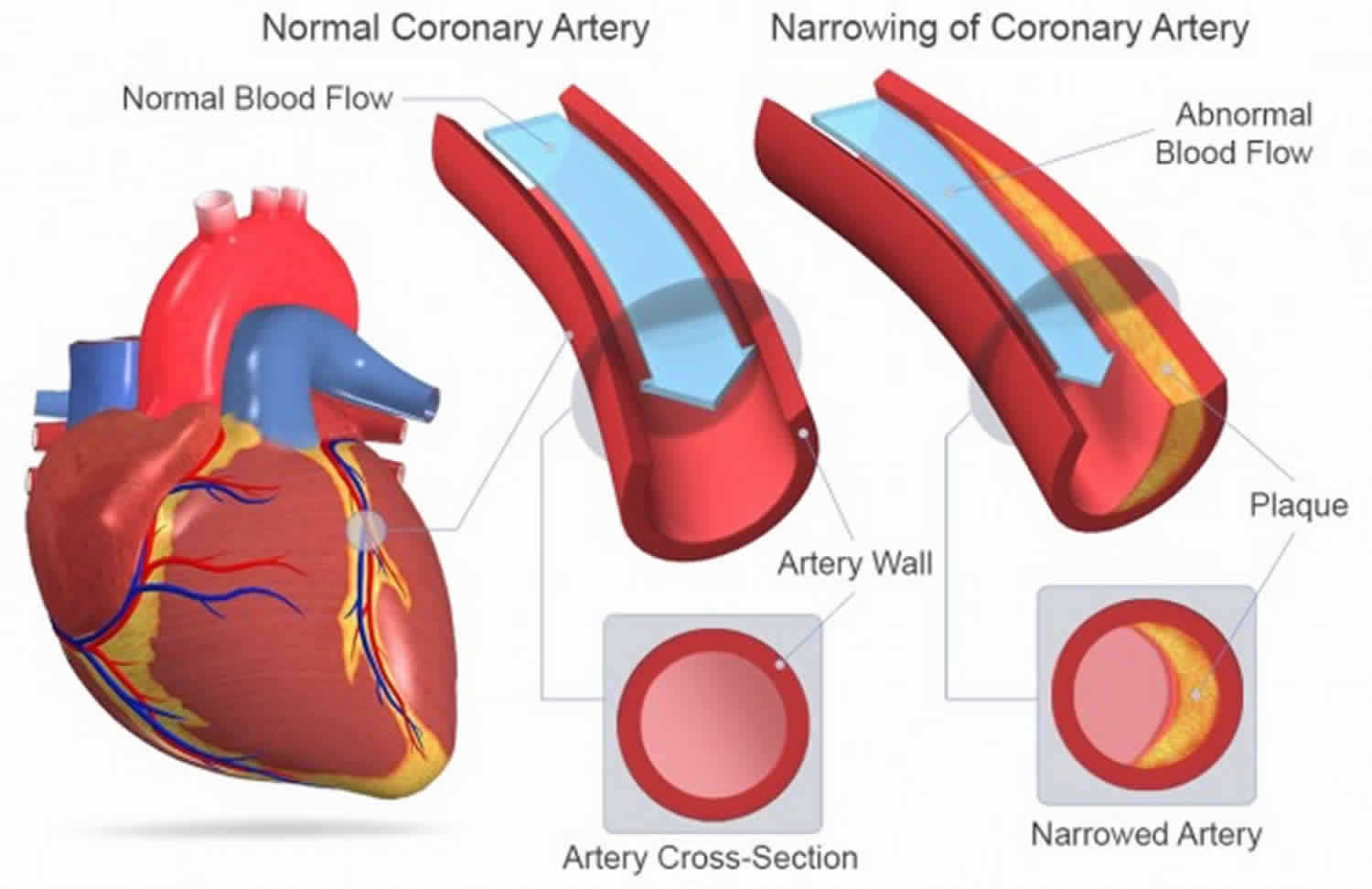

Figure 2. Atherosclerosis blocking the coronary artery in the heart

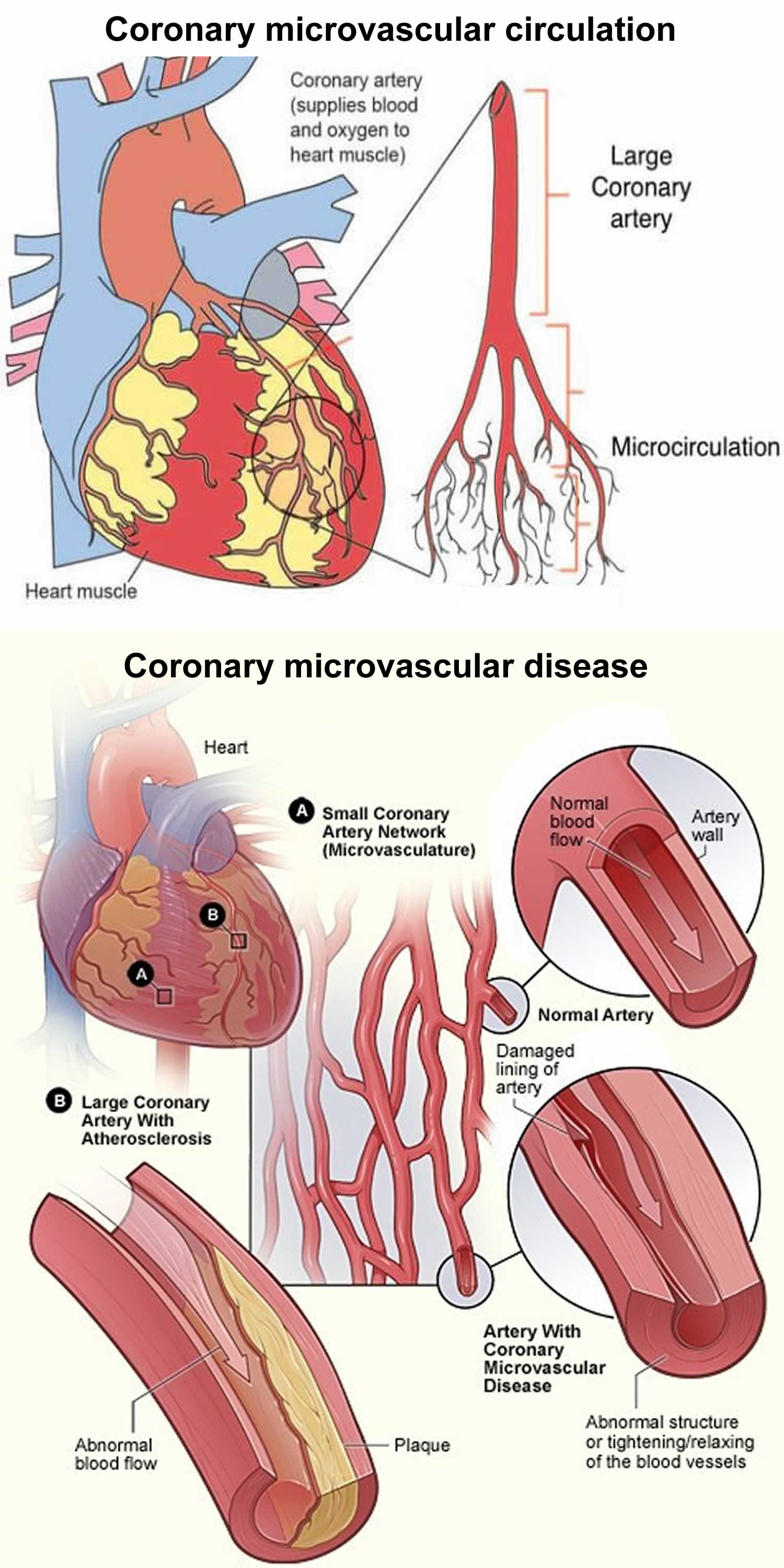

Figure 3. Coronary microvascular disease

Angina can be a warning sign that you are at increased risk of a heart attack. If your chest pain lasts longer than a few minutes and doesn’t go away when you rest or take your angina medications, it may be a sign you’re having a heart attack. Call your local emergency services number or emergency medical help. Only drive yourself to the hospital if there is no other transportation option.

If chest discomfort is a new symptom for you, it’s important to see your doctor to determine the cause and to get proper treatment. If you’ve been diagnosed with stable angina and it gets worse or changes, seek medical help immediately.

The chest pain that occurs with angina can make doing some activities, such as walking, uncomfortable. However, the most dangerous angina complication is a heart attack.

Warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack include:

- Pressure, fullness or a squeezing pain in the center of the chest that lasts for more than a few minutes

- Pain extending beyond the chest to the shoulder, arm, back, or even to the teeth and jaw

- Fainting

- Impending sense of doom

- Increasing episodes of chest pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Continued pain in the upper belly area (abdomen)

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

If you have any of these symptoms, seek emergency medical attention immediately.

What’s the difference between angina and a heart attack?

It can be very difficult to tell if your chest pain or symptoms are angina or if they are due to a heart attack, as the symptoms can be similar. If it’s angina, your symptoms usually ease or go away after a few minutes’ rest, or after taking the medicines your doctor has prescribed for you, such as nitrates. A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart suddenly becomes blocked. Without the blood coming in, the heart can’t get oxygen. If not treated quickly, the heart muscle begins to die. Most heart attacks happen when a blood clot suddenly cuts off the hearts’ blood supply, causing permanent heart damage. The most common cause of heart attacks is coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease). A less common cause of heart attack is a severe spasm (tightening) of a coronary artery. The spasm cuts off blood flow through the coronary artery. If you’re having a heart attack, your symptoms are less likely to ease or go away after resting or taking medicines.

At the hospital, doctors make a diagnosis of angina or a heart attack based on your symptoms, blood tests, and different heart health tests. Treatments may include medicines and medical procedures such as coronary angioplasty. After a heart attack, cardiac rehabilitation and lifestyle changes can help you recover.

Types of angina

There are three types of angina. The type depends on the cause and whether rest or medication relieve symptoms:

- Stable angina or angina pectoris. Stable angina is the most common type of angina. The term angina pectoris is derived from Latin, meaning “strangling of the chest” 1. Stable angina (angina pectoris) occurs when your heart muscle is not getting enough blood flow during periods of physical activity. Stable angina has a regular pattern. Stable angina is usually treated over a longer period. Treatment includes medicines as well as a gradual reintroduction to exercise. This is offered as part of a cardiac rehabilitation program. This improves your heart’s activity and can reduce risk factors that help the condition progress.

- Unstable angina. Unstable angina is the most serious angina and it’s a medical emergency. Unstable angina can be a warning of a heart attack. Unstable angina is when you have symptoms that you have developed for the first time, or angina which was previously stable but has recently got worse or changed in pattern. Unstable angina can occur without warning—even when you are not being physically active or with less stress than usual, and may even come on while you are resting. And it does not follow a pattern. Unstable angina lasts longer than stable angina. Rest and medicine do not relieve unstable angina.

- Variant angina or Prinzmetal’s angina. Variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina) is rare. Variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina) typically happens during the night or early morning when you are at rest. Variant angina can cause severe pain. Medicines can help.

- Refractory angina. Refractory angina episodes are frequent despite a combination of medications and lifestyle changes.

Stable angina

Stable angina also known as angina pectoris, is a type of chest pain, pressure or discomfort you feel when blood flow to your heart is reduced, preventing the heart muscle from receiving enough oxygen. The reduced blood flow is usually the result of a partial or complete blockage of your heart’s arteries (coronary arteries). Stable angina (angina pectoris) usually occurs in individuals with atherosclerosis (thickening or hardening of the arteries caused by a buildup of plaque, which are made up of deposits of fatty substances, cholesterol, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin) whose coronary arteries have been narrowed as a result. The chest pain is typically brought on physical activity (exertion) or emotional stress and does not occur at rest. For example, chest pain, pressure or discomfort that comes on when you’re walking uphill or in the cold weather may be angina. Stable angina pain is predictable and usually similar to previous episodes of chest pain. The chest pain typically lasts a short time, perhaps five minutes or less.

Stable angina is completely relieved by rest or the administration of sublingual nitroglycerine.

There are 2 other forms of angina pectoris. They are:

- Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina

- Microvascular angina or nonobstructive coronary heart disease

Unstable angina

Unstable angina sometimes referred to as acute coronary syndrome causes unexpected chest pain, and usually occurs while resting. Unstable angina is the most serious angina and it’s a medical emergency, since it can progress to a heart attack 2. Medical attention may be needed right away to restore blood flow to the heart muscle. Unstable angina is unpredictable and occurs at rest. Unstable angina may be new or occur more often and be more severe than stable angina. Unstable angina can also occur with or without physical exertion or occurs with less physical effort. Unstable angina is chest pain that is sudden and often gets worse over a short period of time. It’s typically severe and lasts longer than stable angina, maybe 20 minutes or longer. The pain doesn’t go away with rest or the usual angina medications. If the blood flow doesn’t improve, the heart is starved of oxygen and a heart attack occurs. Unstable angina is dangerous and requires emergency treatment.

You may be developing unstable angina if your chest pain:

- Starts to feel different, is more severe, comes more often, or occurs with less activity or while you are at rest

- Lasts longer than 15 to 20 minutes

- Occurs without cause (for example, while you are asleep or sitting quietly)

- Does not respond well to a medicine called nitroglycerin (especially if this medicine worked to relieve chest pain in the past)

- Occurs with a drop in blood pressure or shortness of breath

Unstable angina is a warning sign that a heart attack may happen soon and needs to be treated right away. See your health care provider if you have any type of chest pain.

Coronary artery disease due to atherosclerosis is the most common cause of unstable angina 3. Atherosclerosis is the buildup of fatty material, called plaque, along the walls of the arteries. This causes arteries to become narrowed and less flexible. The narrowing can reduce blood flow to the heart, causing chest pain. The most common cause of unstable angina is due to coronary artery narrowing due to a blood clots that block an artery partially or totally that develops on a disrupted atherosclerotic plaque and is nonocclusive 3. Blood clots may form, partially dissolve, and later form again and angina can occur each time a clot blocks blood flow in an artery.

Rare causes of angina are 2:

- Abnormal function of tiny branch arteries without narrowing of larger arteries (called microvascular dysfunction or cardiac syndrome X)

- Coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal’s angina). Endothelial or vascular smooth dysfunction causes vasospasm of a coronary artery 4

Unstable angina results when the blood flow is impeded to the heart muscle (myocardium). Most commonly, this block can be from intraluminal plaque formation, intraluminal thrombosis, vasospasm, and elevated blood pressure. Often a combination of these is the provoking factor.

Unstable angina is a sign of more severe heart disease. Unstable angina may lead to:

- Abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias)

- A heart attack

- Heart failure

How well you do depends on many different things, including:

- How many and which arteries in your heart are blocked, and how severe the blockage is

- If you have ever had a heart attack

- How well your heart muscle is able to pump blood out to your body

Abnormal heart rhythms and heart attacks can cause sudden death.

If you have unstable angina, you may need to check into the hospital to get some rest, have more tests, and prevent complications.

First, your healthcare provider will need to find the blocked part or parts of the coronary arteries by performing a cardiac catheterization or coronary angiography. In this procedure, a catheter is guided through an artery in your arm or leg and into the coronary arteries, then injected with a liquid dye through the catheter. High-speed X-ray movies record the course of the dye as it flows through the arteries, and doctors can identify blockages by tracing the flow. An evaluation of how well your heart is working also can be done during cardiac catheterization.

Next, based on the extent of the coronary artery blockage(s) your doctor will discuss with you the following treatment options:

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants) are used to treat and prevent unstable angina. You will receive these drugs as soon as possible if you can take them safely.

- Antiplatelet agents include aspirin and the prescription drug clopidogrel or something similar (ticagrelor, prasugrel). These medicines may be able to reduce the chance of a heart attack or the severity of a heart attack that occurs. Dual therapy with aspirin and either clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) decreases the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes, acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), cardiovascular death, and stroke 5, 6.

- During an unstable angina event:

- You may get heparin (or another blood thinner) and nitroglycerin (under the tongue or through an IV). Anticoagulants (blood thinners) – reduce mortality by decreasing re-infarction rates in combination with antiplatelet agents. Used intravenously for acute treatment of unstable angina 5.

- Other treatments may include medicines to control blood pressure, anxiety, abnormal heart rhythms, and cholesterol (such as a statin drug).

- A procedure called percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) and stenting can often be done to open a blocked or narrowed coronary artery.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) also called coronary angioplasty, is a nonsurgical but invasive procedure that improves blood flow to our heart. Doctors use percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) to open coronary arteries to the heart that are narrowed or blocked by plaque buildup. It is commonly used to open a blocked artery in patients suffering a heart attack due to a blocked coronary artery. Coronary angioplasty requires cardiac catheterization. A cardiologist, the doctor who specializes in the heart, performs percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) in a hospital cardiac catheterization laboratory. Live X-rays help your doctor guide a catheter through your blood vessels into your heart, where special contrast dye is injected to highlight any blockage. To open a blocked artery, your doctor will insert another catheter with a small inflatable balloon at the tip of that catheter over a guidewire. The balloon is inflated, squeezing open the fatty plaque deposit located on the inner lining of the coronary artery. Then the balloon is deflated and the catheter is withdrawn. Your doctor may also put a small mesh tube called a stent in your artery to help keep the artery open to allow for improved blood flow to the heart muscle. You may develop a bruise and soreness where the catheters were inserted. It also is common to have discomfort or bleeding where the catheters were inserted. You will recover in a special unit of the hospital for a few hours or overnight. You will get instructions on how much activity you can do and what medicines to take. You will need a ride home because of the medicines and anesthesia you received. Your doctor will check your progress during a follow-up visit. If a stent is implanted, you will have to take certain anticlotting medicines exactly as prescribed, usually for at least 3 to 12 months, but sometimes longer. Serious complications during or after a percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) procedure or as you are recovering after one are rare, but they can happen. This might include:

- Bleeding

- Blood vessel damage

- Treatable allergic reaction to the contrast dye

- Need for emergency coronary artery bypass grafting during the procedure

- Arrhythmias, or irregular heartbeats

- Kidney damage

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Blood clots

- Sometimes chest pain can occur during percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) because the balloon briefly blocks blood supply to the heart. Restenosis, when tissue regrows where the artery was treated, may occur in the months after percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty). This may cause the artery to become narrow or blocked again. The risk of complications from this procedure is higher if you are older, have chronic kidney disease, are experiencing heart failure at the time of the procedure, or have extensive heart disease and more than one blockage in your coronary arteries.

- A coronary artery stent is a small, metal mesh tube that opens up (expands) inside a coronary artery. A stent is often placed after coronary angioplasty. It helps prevent the artery from closing up again. The most common complication after a stenting procedure is a blockage or blood clot in the stent. A drug-eluting stent has medicine in it that helps prevent the artery from closing over time. You may need to take certain medicines, such as aspirin and other anti-clotting or anti-platelet medicines, for a year or longer after receiving a stent in an artery, to prevent serious complications such as blood clots.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) also called coronary angioplasty, is a nonsurgical but invasive procedure that improves blood flow to our heart. Doctors use percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) to open coronary arteries to the heart that are narrowed or blocked by plaque buildup. It is commonly used to open a blocked artery in patients suffering a heart attack due to a blocked coronary artery. Coronary angioplasty requires cardiac catheterization. A cardiologist, the doctor who specializes in the heart, performs percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) in a hospital cardiac catheterization laboratory. Live X-rays help your doctor guide a catheter through your blood vessels into your heart, where special contrast dye is injected to highlight any blockage. To open a blocked artery, your doctor will insert another catheter with a small inflatable balloon at the tip of that catheter over a guidewire. The balloon is inflated, squeezing open the fatty plaque deposit located on the inner lining of the coronary artery. Then the balloon is deflated and the catheter is withdrawn. Your doctor may also put a small mesh tube called a stent in your artery to help keep the artery open to allow for improved blood flow to the heart muscle. You may develop a bruise and soreness where the catheters were inserted. It also is common to have discomfort or bleeding where the catheters were inserted. You will recover in a special unit of the hospital for a few hours or overnight. You will get instructions on how much activity you can do and what medicines to take. You will need a ride home because of the medicines and anesthesia you received. Your doctor will check your progress during a follow-up visit. If a stent is implanted, you will have to take certain anticlotting medicines exactly as prescribed, usually for at least 3 to 12 months, but sometimes longer. Serious complications during or after a percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) procedure or as you are recovering after one are rare, but they can happen. This might include:

- Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG or bypass surgery) may be done for some people depending on the extent of coronary artery blockages and medical history. In this procedure, the surgeon creates new paths for blood to flow to the heart when the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart itself are narrowed or blocked. The surgeon attaches a healthy piece of blood vessel from another part of the body on either side of a coronary artery blockage to bypass it. This surgery may lower the risk of serious complications for people who have obstructive coronary artery disease, which can cause chest pain or even heart failure. It may also be used in an emergency, such as a severe heart attack, to restore blood flow. Heart bypass surgery may be done for some people. The decision to have this surgery depends on:

- Which arteries are blocked

- How many arteries are involved

- Which parts of the coronary arteries are narrowed

- How severe the narrowings are

Variant angina or Prinzmetal’s angina

Variant angina also known as Prinzmetal’s angina, variant angina pectoris or vasospastic angina, is caused by spasm of the coronary artery that temporarily reduces blood flow to the heart muscles 7, 8. The coronary arteries may develop spasm as a result of exposure to cold weather, cold water, exercise, or a substance that promotes vasoconstriction as alpha-agonists (pseudoephedrine and oxymetazoline). Recreational drug use, for example, cocaine, amphetamines, alcohol, and marijuana use, is associated with the development of vasospastic angina, especially when used concurrently with cigarette smoking 9. Valsalva maneuver, hyperventilation, and coronary manipulation through cardiac catheterization also can produce hyperreactivity of the coronaries. Typical cardiovascular risk factors have not directly been associated with the presence of vasospastic angina, except for cigarette smoking and inflammatory states determined by high high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels 10. A metabolic disorder such as insulin resistance has also been associated with vasospastic angina 10.

Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina occurs almost only when you are at rest, with transient ischemic electrocardiographic changes in the ST segment, with a prompt response to nitrates 10. Severe chest pain is the main symptom of variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina). Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina often doesn’t follow a period of physical exertion or emotional stress.

Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina is more common in women. Some studies show that the Japanese population has an increased risk of developing variant angina (Prinzmetal’s angina) when compared with Caucasian populations 11. The difference between the Japanese population and the Caucasian population is that the former has a three times higher risk. The average age of presentation of vasospastic angina is around the fifth decade of life. Females are more likely within the Japanese population to experience vasospastic angina 12.

Patients with vasospastic angina or Prinzmetal’s angina may present with the following:

- Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina can be very painful and usually occurs in cycles, typically at rest and overnight between midnight and 8 a.m.

- A chronic pattern of episodes of chest pain at rest that last 5 to 15 minutes, from midnight to early morning.

- Chest pain decreases with the use of short-acting nitrates.

- Typically, these patients have ischemic ST-segment changes on an electrocardiogram during an episode of chest discomfort, which returns to baseline on symptom resolution.

- Typically, the chest pain is not triggered by exertion or alleviated with rest as is typical angina.

- Often, the patient is younger with few or no classical cardiovascular risk factors.

Other vasospastic disorders, like Raynaud phenomenon or a migraine, can be associated with this subset of patients. Patients may complain of recent or past episodes with some symptom-free periods.

The international study group of coronary vasomotion disorders (COVADIS), created a diagnostic criterion to determine the presence of Prinzmetal angina. Vasospastic angina diagnostic criteria elements 13:

- Nitrate-responsive angina — during spontaneous episode, with at least one of the following:

- (a) Rest angina—especially between night and early morning

- (b) Marked diurnal variation in exercise tolerance—reduced in morning

- (c) Hyperventilation can precipitate an episode

- (d) Calcium channel blockers (but not β-blockers) suppress episodes

- Transient ischemic ECG charges — during spontaneous episode, including any of the following in at least two contiguous leads:

- (a) ST segment elevation ≥ 0.1 mV

- (b) ST segment depression ≥ 0.1 mV

- (c) New negative U waves

- Coronary artery spasm — defined as transient total or subtotal coronary artery occlusion (>90% constriction) with angina and ischemic ECG changes either spontaneously or in response to a provocative stimulus (typically acetylcholine ergot, or hyperventilation)

Footnotes:

- ‘Definitive vasospastic angina’ is diagnosed if nitrate-responsive angina is evident during spontaneous episodes and either transient ischemic ECG changes during the spontaneous episodes or coronary artery spasm criteria are fulfilled.

- ‘Suspected vasospasic angina’ is diagnosed if nitrate-responsive angina is evident during spontaneous episodes but transient ischemic ECG changes are equivocal or unavailable and coronary artery spasm criteria are equivocal.

Variant angina pectoris or Prinzmetal’s angina pain may be relieved by medicines such as calcium channel blockers. These medicines help dilate the coronary arteries and prevent spasm 10.

- Calcium channel blockers (calcium antagonists) play an important role in the management of vasospastic angina. It is a first-line treatment due to a vasodilation effect in the coronary vasculature. Calcium antagonist is effective in alleviating symptoms in 90% of patients. Moreover, one study demonstrated that the use of calcium channel blocker therapy was an independent predictor of myocardial infarct-free survival in vasospastic angina patients.

- The use of a long-acting calcium channel blocker (calcium antagonist) is recommended to be given at night as the episodes of vasospasm are more frequent at midnight and early in the morning. A high dose of long-acting calcium antagonists like diltiazem, amlodipine, nifedipine, or verapamil are recommended, and titration should be done on an individual basis with an adequate response and minimal side effects. In some cases, the use of a two-calcium antagonist (dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine) can be effective in patients with poor response to one agent.

- The use of long-acting nitrates are also effective in preventing vasospastic events, but chronic use is associated with tolerance. In patients on calcium antagonist without an adequate response to treatment, long-acting nitrates can be added.

- Nicorandil, a nitrate, and K-channel activator also suppress vasospastic attacks.

- The use of beta-blockers, especially those with nonselective adrenoceptor blocking effects, should be avoided because these drugs can aggravate the symptoms.

- Treatment with guanethidine, clonidine, or cilostazol has been reported to be beneficial in patients taking calcium channel antagonists. However, these drugs are not well-studied in this setting.

- The use of fluvastatin has been shown to be effective in preventing coronary spasm and may exert benefits via endothelial nitric oxide or direct effects on the vascular smooth muscle.

Microvascular angina

Microvascular angina also known as “cardiac syndrome X” or nonobstructive coronary heart disease, is more common in women particularly in perimenopausal and postmenopausal females 14, 15. Doctors have found that the pain of microvascular angina results from poor function of tiny blood vessels nourishing the heart (coronary microvascular disease), as well as the arms and legs. The prevalence of microvascular angina is estimated to be up to 30% of stable angina patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries 16. Classic microvascular angina is defined as a disease entity with (1) effort angina; (2) findings compatible with myocardial ischemia/coronary microvascular dysfunction upon diagnostic investigation; (3) the appearance of normal or near normal coronary arteries on angiography; and (4) absence of any other specific cardiac disease, such as variant angina, cardiomyopathy, or valvular disease 17. Findings compatible with myocardial ischemia include: (1) diagnostic ST segment depression during spontaneous or stress-induced typical chest pain; (2) reversible perfusion defects on stress myocardial scintigraphy; (3) documentation of stress-related coronary blood flow abnormalities using more advanced diagnostic techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance (MR), positron emission tomography (PET) or Doppler ultrasound; (4) metabolic evidence of transient myocardial ischemia (cardiac PET or MR, invasive assessment) 16.

The causes of microvascular angina aren’t fully known, although there different mechanisms and theories of the condition have been reported 18. These include problems with the inner lining of the small blood vessels, changes in the size and number of these vessels, problems with these vessels expanding to allow more blood to the heart during exercise or when you feel stressed or spasms within the walls of these very small arterial blood vessels causing reduced blood flow to the heart muscle. Another commonly hypothesized cause is heightened cardiac pain sensitivity, termed “hyperalgesia.” Microvascular angina is considered in patients with typical anginal chest pain and microvascular dysfunction of the coronary vessels after stressors such as exercise, which did not exhibit any evidence of ischemia of the myocardium by angiography 15. Patients with established microvascular angina often tend to have unfavorable cardiovascular events, leading to recurring hospitalizations, decreased quality of life, and poor prognostic outcomes. The challenge of achieving therapeutic efficacy from pharmacotherapy also poses additional barriers as traditional therapy for managing anginal chest pain is often unsuccessful. This often prolongs microvascular angina symptoms, prompts hospital admissions, restraining daily activities, and inability to attend work.

Subjects who have established microvascular angina have a 30% greater probability of presenting with underlying metabolic comorbid conditions when compared to the general population (8%). Potential contributing factors to the pathogenesis of microvascular angina and coronary microvascular dysfunction include insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, enhanced sodium-hydrogen exchange in red blood cells, chronic inflammation with elevated C-reactive protein levels (CRP), and vascular or nonvascular smooth muscle dysfunction 19.

Research shows that people with microvascular angina may be at increased risk of a heart attack or other heart problems. If you have been diagnosed with microvascular angina and you feel chest pain that does not go away after around 15 minutes, you should still call your local emergency services number immediately and ask for an ambulance.

Coronary microvascular disease sometimes called small artery disease or small vessel disease, is heart disease that affects the walls and inner lining of tiny coronary artery blood vessels that branch off from the larger coronary arteries 20. Coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease) involves plaque formation that can block blood flow to the heart muscle. In contrast, coronary microvascular disease, the heart’s coronary artery blood vessels don’t have plaque, but damage to the inner walls of the blood vessels can lead to spasms and decrease blood flow to the heart muscle. In addition, abnormalities in smaller arteries that branch off of the main coronary arteries may also contribute to coronary microvascular disease. People with microvascular angina have chest pain but have no apparent coronary artery blockages. Microvascular angina can be treated with some of the same medicines used for stable angina (angina pectoris).

Angina that occurs in coronary microvascular disease may differ from the typical angina that occurs in heart disease in that the chest pain usually lasts longer than 10 minutes, and it can last longer than 30 minutes. If you have been diagnosed with coronary microvascular disease, follow the directions from your healthcare provider regarding how to treat your symptoms and when to seek emergency assistance.

Microvascular angina chest pain or discomfort:

- May be more severe and last longer than other types of angina pain

- May occur with shortness of breath, sleep problems, fatigue, and lack of energy

- Often people who experience coronary microvascular disease symptoms often first notice them during their routine daily activities and times of mental stress. They occur less often during physical activity or exertion. This differs from disease of the major coronary arteries and main branches, in which symptoms usually first appear during physical activity.

The risk factors for coronary microvascular disease are the same as for coronary artery disease, including diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Many researchers think some of the risk factors that cause atherosclerosis may also lead to coronary microvascular disease. Atherosclerosis is a disease in which plaque builds up inside the arteries. Risk factors for atherosclerosis include:

- Unhealthy blood cholesterol levels

- High blood pressure

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Overweight and obesity

- Lack of physical activity

- Unhealthy diet

- Older age

- Family history of heart disease

No studies have been done on how to prevent coronary microvascular disease. Researchers don’t yet know how or in what way preventing coronary microvascular disease differs from preventing heart disease.

Knowing your family history of heart disease, making the following lifestyle changes and ongoing care can help you lower your risk for heart disease.

- Manage blood pressure

- Control cholesterol

- Reduce blood sugar

- Get active

- Eat better

- Lose or manage weight

- Stop smoking

Microvascular angina is primarily a diagnosis of occlusion, which further prompts extensive workup and assessment that can be costly and time-consuming 18. Patients present with typical or atypical anginal chest pain, ST depression, and no evidence of coronary vessel obstruction greater than 50% on angiography 18.

Research to identify better ways to detect and diagnose coronary microvascular disease is ongoing. Diagnosing coronary microvascular disease was previously a challenge. Standard tests for coronary artery disease may not be able to detect coronary coronary microvascular disease. These tests look for blockages in the large coronary arteries. Coronary microvascular disease affects the tiny coronary arteries. If you have angina but tests show your coronary arteries are normal, you could still have coronary microvascular disease. PET scans and MRI imaging are now available which measure blood flow through the coronary arteries and can detect coronary coronary microvascular disease in very small blood vessels.

Newer tests to assess small vessel function in the heart include:

- Using small guidewires, about the thickness of a human hair, passed into a coronary artery during an angiogram in order to measure blood vessel function.

- A test using a drug called acetylcholine.

The Coronary Vasomotion Disorders International Study (COVADIS) Group define microvascular angina as symptoms of myocardial ischemia with proven coronary microvascular dysfunction (e.g. index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) ≥25, coronary flow reserve (CFR) <2.0 or abnormal microvascular constriction during acetylcholine infusion), with unobstructed epicardial coronary arteries 21.

Microvascular angina clinical diagnostic criteria 22:

- Symptoms of myocardial ischemia

- a) Effort and/or rest angina

- b) Angina equivalents (i.e. shortness of breath)

- Absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (<50% diameter reduction and/or Fractional Flow Reserve [FFR] by >0.80) by

- a) Coronary CT angiography

- b) Invasive coronary angiography

- Objective evidence of myocardial ischemia

- a) Ischemic ECG changes during an episode of chest pain

- b) Stress-induced chest pain and/or ischemic ECG changes in the presence or absence of transient/reversible abnormal myocardial perfusion and/or wall motion abnormality

- Evidence of impaired coronary microvascular function

- a) Impaired coronary flow reserve (cut-off values depending on methodology use between ≤2.0 and ≤2.5)

- b) Abnormal coronary microvascular resistance indices (e.g. index of microvascular resistance (IMR) > 25) 23

- c) Coronary microvascular spasm, defined as reproduction of symptoms, ischemic ECG shifts but no epicardial spasm during acetylcholine testing.

- d) Coronary slow flow phenomenon, defined as TIMI frame count (TFC) >25.

Additional testing can confirm the diagnosis.

Coronary microvascular disease symptoms often first occur during routine daily tasks. Because of this, you may be asked to fill out a questionnaire called the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI). The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) is a patient-reported estimate of functional capacity, maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) and maximum metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs) 24. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) includes questions about how well you’re able to do daily activities, such as shopping, cooking and going to work. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) results can help determine what additional tests are needed to make the diagnosis of coronary microvascular disease 25.

The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) is a self-administered questionnaire that measures a person’s functional capacity. The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) questionnaire produces a score between 0 and 58.2 points, which is linearly correlated with a patient’s maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) and maximum metabolic equivalent of tasks (METs), as measured from cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

The Duke Activity Status Index Questionnaire 24:

- Can you take care of yourself (eating, dressing, bathing or using the toilet)?

- Yes (+ 2.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you walk indoors, such as around your house?

- Yes (+ 1.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you walk a block or two on level ground?

- Yes (+ 2.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you climb a flight of stairs or walk up a hill?

- Yes (+ 5.50)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you run a short distance?

- Yes (+ 8.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do light work around the house, such as dusting or washing dishes?

- Yes (+ 2.75)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do moderate work around the house, such as vacuuming, sweeping floors or carrying in groceries?

- Yes (+ 3.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do heavy work around the house, such as scrubbing floors or lifting and moving heavy furniture?

- Yes (+ 8.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you do yard work, such as raking leaves, weeding or pushing a power mower?

- Yes (+ 4.5)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you have sexual relations?

- Yes (+ 5.25)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you participate in moderate recreational activities, such as golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis or throwing a baseball or football?

- Yes (+ 6.0)

- No (+ 0.0)

- Can you participate in strenuous sports, such as swimming, singles tennis, football, basketball or skiing?

- Yes (+ 7.50)

- No (+ 0.0)

Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) = sum of “Yes” replies ___________ (the higher the score (maximum 58.2), the higher the functional status.)

VO2max (in mL/kg/min) = (0.43 x DASI) + 9.6

VO2max = ___________ ml/kg/min ÷ 3.5 ml/kg/min = __________ METS (maximum metabolic equivalent of tasks)

The management of patients suspected of having microvascular angina is challenging and complex as its cause is not entirely understood. To date, there are no specific guidelines to treat microvascular angina, and management should be initiated on a case by case basis.

Treatment of coronary microvascular disease involves pain relief, controlling risk factors and other symptoms.

Microvascular angina treatments may include medicines such as:

- Cholesterol medication to improve cholesterol levels.

- Blood pressure medications to lower high blood pressure and decrease the heart’s workload.

- Antiplatelet medication to help prevent blood clots.

- Medications to relax blood vessels including beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and nitroglycerin.

- Nitroglycerin to treat chest pain.

Pharmacologic management of microvascular angina can be initiated by conventional anti-ischemic agents such as beta-blockers, nitrates, and calcium channel blockers. Additional agents like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, statins, and antianginals such as ranolazine may also be used. Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, verapamil, diltiazem) may be an alternative therapy to beta-blockers if a therapeutic response is not achieved 26. Although calcium channel blockers increase exercise tolerance and minimize the episodes of angina, they are reported to be not as effective as beta-blockers in patients with microvascular angina. Ranolazine, a recent antianginal indicated for chronic angina used in patients with refractory angina, has also been reported to be an effective alternative for therapy. Ranolazine’s function to regulate neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels plays a role in managing potential neuropathic pain in patients with microvascular angina. A Seattle Angina Questionnaire reported ranolazine as a beneficial agent in females with anginal symptoms and no reported evidence of coronary artery obstruction 27.

Statins enhance the endothelium’s vasodilatory effects and may be effective in patients with microvascular angina. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have also been reported to be beneficial. They impede endothelial bradykinin degradation, which results in vasodilatory effects 26. These effects may further regulate the microvascular tone of the coronary vessels.

Based on the hypothesis of altered pain perception in patients with microvascular angina, analgesic pharmacotherapy may be effective. Pain management with agents like tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and xanthine derivatives (adenosine receptor blockers) have been reported to show effectiveness.

Agents such as xanthine derivatives (adenosine receptor blockers), aminophylline, and imipramine have been proposed in select patients. Imipramine has been reported to decrease the frequency of chest pain by roughly 50% 18. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) action of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibition exerts analgesic action; hence their proposed benefits in patients with microvascular angina. Imipramine is also advised by the American College of Cardiology for microvascular angina patients unresponsive to beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates. Imipramine, used in the management of microvascular angina, has been controversial due to its adverse effects.

Lifestyle changes or improvements are also recommended, other treatment modalities such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and neural electrical stimulation may be considered in select patients 28. Neural electrical stimulation procedures target increased pain sensitivity in microvascular angina and are utilized in subjects resistant to pharmacotherapy. Procedures include spinal cord stimulation and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). The therapeutic effects reportedly enhance parasympathetic activity, further improving endothelial dysfunction and pain sensitivity. Other reported actions include increasing blood flow in the coronary vessels by spinal cord stimulation.

The intensity of microvascular angina symptoms is reported to reduce in 30% of subjects but may progressively worsen in approximately 20% of patients over time 29, 15. A study conducted on a cohort of female subjects reported 45% of individuals with chest pain and no evidence of coronary artery obstruction by imaging (angiography) reported ongoing typical or atypical chest pain persisting greater than 12 months. The study also reported subjects to have twice the risk for adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction [heart attack], stroke, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality).

Progressive disease comprises regular and lengthy anginal chest pains that manifest at decreased exertion levels and may even occur at rest. Some subjects may also experience a disease course resistant to pharmacological management, which further diminishes the quality of life. Patients with a progressive disease course may require drastic diagnostics that could lead to functional disability 15.

Angina signs and symptoms

Angina symptoms include chest pain and discomfort. The chest pain or discomfort may feel like:

- Burning

- Fullness

- Pressure

- Squeezing

Pain may also be felt in the arms, neck, jaw, shoulder or back.

Other symptoms of angina include:

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

Angina symptoms are not the same for everyone. The severity, duration and type of angina can vary. New or different symptoms may signal a more dangerous form of angina (unstable angina) or a heart attack.

Any new or worsening angina symptoms will need to be evaluated immediately by a health care provider who can determine whether you have stable or unstable angina.

You might experience angina if it is a cold day, or if you’re walking after a meal. Being very upset can sometimes trigger an angina episode too. Or you may get angina if you’re exerting yourself, for

example, during activities such as exercise or sexual intercourse.

The symptoms of angina usually fade after a few minutes’ rest, or after taking the medicines that your doctor or nurse may have prescribed for you, such as glyceryl trinitrate (GTN).

Each type of angina has certain typical symptoms.

Stable angina symptoms

- Discomfort that feels like gas or indigestion

- Pain during physical exertion or mental stress

- Pain that spreads from your breastbone to your arms or back

- Pain that is relieved by medicines

- Pattern of symptoms that has not changed in the last 2 months

- Symptoms that go away within 5 minutes

Unstable angina symptoms

- Changes in your stable angina symptoms

- Pain that grows worse

- Pain that is not relieved by rest or medicines

- Pain that lasts longer than 20 minutes or goes away and then comes back

- Pain while you are resting or sleeping

- Severe pain

- Shortness of breath

Microvascular angina symptoms

- Pain after physical or emotional stress

- Pain that is not immediately relieved by medicines

- Pain that lasts a long time

- Pain that you feel while doing regular daily activities

- Severe pain

- Shortness of breath

Variant angina or Prinzmetal angina symptoms

- Cold sweats

- Fainting

- Numbness or weakness of the left shoulder and upper arm

- Pain that is relieved by medicines

- Pain that occurs during rest or while sleeping

- Pain that starts in the early morning hours

- Severe pain

- Vague pain with a feeling of pressure in the lower chest, perhaps spreading to the neck, jaw, or left shoulder

Angina in women

Symptoms of angina in women can be different from the classic angina symptoms in men. These differences may lead to delays in seeking treatment. For example, chest pain is a common symptom in women with angina, but it may not be the only symptom or the most prevalent symptom for women. Women may also have symptoms such as:

- Discomfort in the neck, jaw, teeth or back

- Nausea

- Shortness of breath

- Stabbing pain instead of chest pressure

- Stomach (abdominal) pain

Heart disease in men is more often due to blockages in their coronary arteries, referred to as obstructive coronary artery disease. Women more frequently develop heart disease within the very small arteries that branch out from the coronary arteries. This is referred to as microvascular disease (microvascular angina) and occurs particularly in younger women. Up to 50% of women with anginal symptoms who undergo cardiac catheterization don’t have the obstructive type of coronary artery disease..

Angina causes

Angina is caused by insufficient blood flow to the muscle of your heart (myocardium). Even though the heart is full of blood, this blood is pumped through the body. The muscles of the heart need their own supply of blood. That blood is carried through the coronary arteries, which sit on the outside of the heart (see Figure 1). The most common cause of reduced blood flow to the heart muscle is coronary artery disease (also known as coronary heart disease). If you have coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease), then these arteries have become narrowed by fatty deposits known as plaques. This is called atherosclerosis. Narrowed coronary arteries can’t carry as much blood as they should. Blood carries oxygen, which the heart muscle needs to survive. When the heart muscle isn’t getting enough oxygen, it causes a condition called ischemia.

If plaques in a blood vessel rupture or a blood clot forms, it can quickly block or reduce flow through a narrowed artery. This can suddenly and severely decrease blood flow to the heart muscle.

During times of low oxygen demand — when resting, for example — the heart muscle may still be able to work on the reduced amount of blood flow without triggering angina symptoms. But when the demand for oxygen goes up, such as when exercising, angina can result.

A spasm that tightens your coronary arteries can also cause angina. Coronary artery spasms can occur whether or not you have coronary heart disease and can affect large or small coronary arteries. Damage to your heart’s arteries may cause them to narrow instead of widen when the heart needs more oxygen-rich blood.

Risk factors for angina

Anything that causes your heart muscle to need more blood or oxygen supply can result in angina. Risk factors include physical activity, emotional stress, extreme cold and heat, heavy meals, drinking excessive alcohol, and cigarette smoking.

The following things may increase your risk of angina:

- Increasing age. Angina is most common in adults age 60 and older.

- Race or ethnicity. Some groups of people are at higher risk for developing coronary heart disease and one of its main symptoms, angina. African Americans who have already had a heart attack are more likely than whites to develop angina. Variant angina is more common among people living in Japan, especially men, than among people living in Western countries.

- Sex. Angina affects both men and women, but at different ages based on men and women’s risk of developing coronary heart disease. In men, heart disease risk starts to increase at age 45. Before age 55, women have a lower risk for heart disease than men. After age 55, the risk rises in both women and men. Women who have already had a heart attack are more likely to develop angina compared with men. Microvascular angina most often begins in women around the time of menopause.

- Environment or occupation factors. Angina may be linked to a type of air pollution called particle pollution. Particle pollution can include dust from roads, farms, dry riverbeds, construction sites, and mines. Your work life can increase your risk of angina. Examples include work that limits your time available for sleep, involves high stress, requires long periods of sitting or standing, is noisy, or exposes you to potential hazards such as radiation.

- Family history of heart disease. Tell your health care provider if your mother, father or any siblings have or had heart disease or a heart attack.

- Family history of premature heart disease. This means if your father or a brother has, or had, angina or a heart attack before the age of 55, or if your mother or a sister has, or had, angina or a heart attack before the age of 65.

- Tobacco use. Smoking, chewing tobacco and long-term exposure to secondhand smoke can damage the lining of the arteries, allowing deposits of cholesterol to collect and block blood flow.

- Diabetes. Diabetes increases the risk of coronary artery disease, which leads to angina and heart attacks by speeding up atherosclerosis and increasing cholesterol levels.

- High blood pressure. Over time, high blood pressure damages arteries by accelerating hardening of the arteries.

- High cholesterol or triglycerides. Too much bad cholesterol —high amount of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) — in the blood can cause arteries to narrow. A high LDL increases the risk of angina and heart attacks. A high level of triglycerides in the blood also is unhealthy.

- Medical conditions in which your heart needs more oxygen-rich blood than your body can supply increase your risk for angina. They include:

- Anemia

- Cardiomyopathy, or disease of the heart muscle

- Heart problems, such as heart failure, heart valve diseases, or high blood pressure

- Inflammation

- Metabolic syndrome

- Other health conditions. Chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, metabolic syndrome or a history of stroke increases the risk of angina.

- Not enough exercise. An inactive lifestyle contributes to high cholesterol, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and obesity. Talk to your health care provider about the type and amount of exercise that’s best for you.

- Obesity. Obesity is a risk factor for heart disease, which can cause angina. Being overweight makes the heart work harder to supply blood to the body.

- Emotional stress. Too much stress and anger can raise blood pressure. Surges of hormones produced during stress can narrow the arteries and worsen angina.

- Medications. Drugs that tighten blood vessels, such as some migraine drugs, may trigger Prinzmetal’s angina (variant angina pectoris).

- Drug misuse. Cocaine and other stimulants can cause blood vessel spasms and trigger angina.

- Cold temperatures. Exposure to cold temperatures can trigger Prinzmetal’s angina (variant angina pectoris).

- Medical procedures. Heart procedures such as stent placement, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) can trigger coronary spasms and angina. Although rare, noncardiac surgery can also trigger unstable angina or variant angina.

Angina prevention

You can help prevent angina by following the same lifestyle changes that are used to treat angina. These include:

- Not smoking.

- Eating a healthy diet.

- Avoiding or limiting alcohol.

- Exercising regularly.

- Maintaining a healthy weight.

- Managing other health conditions related to heart disease.

- Reducing stress.

- Getting recommended vaccines to avoid heart complications.

Angina diagnosis

To help diagnose angina, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and examine you. You’ll also be asked about any risk factors, including whether you have a family history of heart disease.

Tests used to diagnose and confirm angina include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) is a quick and painless test that measures the electrical activity of the heart. Sticky patches (electrodes) are placed on the chest and sometimes the arms and legs. Wires connect the electrodes to a computer, which displays the test results. An ECG can show if the heart is beating too fast, too slow or not at all. Your health care provider also can look for patterns in the heart rhythm to see if blood flow through the heart has been slowed or interrupted.

- Hyperventilation testing. Hyperventilation testing can help diagnose variant angina. Rapid breathing under controlled conditions with careful medical monitoring may bring on electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) changes that help your doctor diagnose variant angina.

- A blood test called troponin that measures damage to the heart muscle. Troponin is a protein found in the muscles of the heart. Normally, troponin levels are close to undetectable in the blood. When heart muscles are injured or damaged, troponin is released into the bloodstream and, as heart damage progresses, greater amounts of troponin may be detected. Doctors commonly test troponin levels several times over a 24-hour period when a person is suspected of having had a heart attack. Testing may also be ordered to evaluate heart injury related to certain medical procedures. A troponin test requires a blood sample and is typically performed in an emergency room, hospital, or similar medical setting.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray shows the condition of the heart and lungs. A chest X-ray may be done to determine if other conditions are causing chest pain symptoms and to see if the heart is enlarged.

- Exercise stress test, which measures blood pressure and heart activity during exercise. Sometimes angina is easier to diagnose when the heart is working harder. A stress test typically involves walking on a treadmill or riding a stationary bike while the heart is monitored. Other tests may be done at the same time as a stress test. If you can’t exercise, you may be given drugs that mimic the effect of exercise on the heart.

- Nuclear stress test also known as a radionuclide scan, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, myoview or thallium scan. A nuclear stress test helps measure blood flow to the heart muscle at rest and during stress. It can show the blood flow to your heart and how your heart functions when it has to work harder – for example, when you’re active. You will be given an injection of a small amount of isotope (a radioactive substance). A large camera is then put in position close to your chest and takes pictures of your heart. These pictures help your doctor to work out if the problem is angina, how much it is affecting the heart, and what treatment would be most helpful.

- Echocardiogram or echo, which uses sound waves to create images of your heart in motion. These images can show how blood flows through the heart. An echocardiogram may be done during a stress test, where it’s called stress echocardiogram. A stress echocardiogram is when the echocardiogram is recorded after the heart has been put under stress – either during exercise or after giving you a particular type of medicine that speeds up the heart to mimic exercise. The test can show if any areas of your heart are getting less blood flow when your heart is working hard. The stress echocardiogram pictures help your doctor to work out if the problem is angina, and how much it is affecting the heart. Your doctor can then decide what treatment might be most helpful.

- Coronary angiography. Coronary angiogram uses X-ray imaging to examine the inside of the heart’s blood vessels. It’s part of a general group of procedures known as cardiac catheterization. A health care provider threads a thin tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in your arm or groin to an artery in your heart and injects dye through the catheter. The dye makes the heart arteries show up more clearly on an X-ray. The dye helps blood vessels show up better on the images and outlines any blockages. Your health care provider might call this type of X-ray an angiogram. If you have an artery blockage that needs treatment, a balloon on the tip of the catheter can be inflated to open the artery. A mesh tube (stent) is typically used to keep the artery open.

- Cardiac computerized tomography (coronary CT). For this test, you typically lie on a table inside a doughnut-shaped machine. An X-ray tube inside the machine rotates around the body and collects images of the heart and chest. A cardiac CT scan can show if the heart is enlarged or if any heart’s arteries are narrowed. Coronary CT can show the blood flow through your coronary arteries and will give you a ‘calcium score’, which is a measure of how much calcium there is in the artery walls. The higher your calcium score is, the higher your risk of having

coronary heart disease. - Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the heart. You typically lie on a table inside a long, tubelike machine that produces detailed images of the heart’s structure and blood vessels.

- Cardiac positron emission tomography (PET) scanning assesses blood flow through the small coronary blood vessels and into the heart tissues. This is a type of nuclear heart scan that can diagnose coronary microvascular disease.

Angina treatment

Angina treatment aims to reduce your symptoms and reduce your risk of heart attack, stroke or death.

Mild angina will respond well to:

- a healthier diet

- increasing physical activity (safely, under the supervision of your doctor)

- reducing stress

- quitting smoking, if you smoke

Your doctor might prescribe nitrates to relax your blood vessels, so more blood flows to your heart. You might also need other heart medications like beta-blockers or aspirin.

You will need immediate treatment if you have unstable angina or angina pain that’s different from what you usually have.

If you have severe angina, you might need surgery such as angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery.

Your doctor might advise you to join a cardiac rehabilitation program, to help you manage your angina and reduce the risk of further heart problems.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Heart disease is often the cause of angina. Making lifestyle changes to keep the heart healthy is an important part of angina treatment. Try these strategies:

- Don’t smoke and avoid exposure to secondhand smoke. If you need help quitting, talk to your health care provider about smoking cessation treatment.

- Exercise and manage your weight. As a general goal, aim to get at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity every day. If you’re overweight, talk to your health care provider about safe weight-loss options. Ask your health care provider what weight is best for you.

- Eat a healthy diet low in salt and saturated and trans fats and rich in whole grains, fruits and vegetables.

- Manage other health conditions. Diabetes, high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol can lead to angina.

- Practice stress relief. Getting more exercise, practicing mindfulness and connecting with others in support groups are some ways to reduce emotional stress.

- Avoid or limit alcohol. If you choose to drink alcohol, do so in moderation. For healthy adults, that means up to one drink a day for women and up to two drinks a day for men.

Angina medications

If lifestyle changes — such as eating healthy and exercising — don’t improve heart health and relieve angina pain, medications may be needed. Not everyone who has angina will be prescribed the same medicines. Your doctor will prescribe the medicines that work best for you.

Medications to treat angina may include:

- Nitrates. Nitrates are often used to treat angina. Nitrates relax and widen the blood vessels so more blood flows to the heart. You may be given nitrates as a fast-acting spray or tablets, as slow-release tablets, or as skin patches. The most common form of nitrate used to treat angina is nitroglycerin. Your doctor will give you a fast-acting nitrate spray or tablets. To relieve an episode of angina, use the spray or tablet under your tongue. It will start acting within a few seconds and the symptoms should go away within a few minutes. Your health care provider might recommend taking a nitrate before activities that typically trigger angina (such as exercise) or on a long-term preventive basis. You should only use your nitroglycerin as a preventer if your doctor has told you to do this and if you know which activities bring on your angina. If you need to take your nitroglycerin medicines more often than usual, you should speak to your doctor. Keep the nitroglycerin tablets in their original container. They will be OK for eight weeks after you have opened the container. After that time they lose their strength so you’ll need to replace them. You can keep nitroglycerin sprays for up to two years after using them for the first time, but always check the instructions on the packaging.

- Slow-release nitrate tablets. If you get regular episodes of angina, your doctor may give you a medicine that helps to prevent you getting the angina. This medicine lasts longer than

nitroglycerin sprays or tablets and can be taken either once or twice a day, depending on your condition. - Nitroglycerin skin patches. Self-adhesive skin patches containing nitroglycerin act in a similar way to slow-release nitrates, but the medicine is absorbed through your skin rather than as a tablet. Usually, you would put on a new patch each morning and take it off at night before going to bed.

- If you’re taking any type of nitrate medicine, you should not take medicines to improve your sex drive or to maintain an erection (PDE-5 inhibitors such as Viagra) without speaking to your doctor first.

- Slow-release nitrate tablets. If you get regular episodes of angina, your doctor may give you a medicine that helps to prevent you getting the angina. This medicine lasts longer than

- Aspirin. Aspirin reduces blood clotting, making it easier for blood to flow through narrowed heart arteries. Preventing blood clots can reduce the risk of a heart attack. Don’t start taking a daily aspirin without talking to your health care provider first.

- Clot-preventing drugs. Certain medications such as clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) make blood platelets less likely to stick together, so blood doesn’t clot. One of these medications may be recommended if you can’t take aspirin.

- Beta blockers. Beta blockers cause the heart to beat more slowly and with less force, which lowers blood pressure. These medicines also relax blood vessels, which improves blood flow. Beta-blockers are very effective in preventing episodes of angina.

- Statins. Statins are drugs used to lower blood cholesterol. High cholesterol is a risk factor for heart disease and angina. Statins block a substance that the body needs to make cholesterol. They help prevent blockages in the blood vessels.

- There are other types of medicines that can be used when statins are not suitable, or that can be used as well as statins. These include fibrates and ezetimibe. You may be given ezetimibe as well as a statin or, if you cannot take a statin, your doctor may give you ezetimibe on its own.

- Calcium channel blockers. Calcium channel blockers also called calcium antagonists, relax and widen blood vessels to improve blood flow. Calcium-channel blockers are used to reduce the frequency of angina attacks. If you have asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or diabetes, your doctor may prescribe calcium-channel blockers for you rather than beta-blockers.

- Potassium-channel activators. Potassium-channel activators have a similar effect to nitrates, as they relax the walls of the coronary arteries and so improve the flow of blood to the heart.

- Other blood pressure medications. Other drugs to lower blood pressure include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs). If you have high blood pressure, diabetes, signs of heart failure or chronic kidney disease, your health care provider may prescribe one of these types of medications.

- Ranolazine (Ranexa). This medication may be prescribed for chronic stable angina that doesn’t get better with other medications. It may be used alone or with other angina medications, such as calcium channel blockers, beta blockers or nitroglycerin. When given with other anti-angina medicines, ranolazine can also increase the length of time you can be physically active without pain. Ranolazine may work for coronary microvascular disease, which causes microvascular angina. Ranolazine may be a substitute for nitrates for men with stable angina who take drugs for erectile dysfunction.

- Morphine relieves pain and help relax the blood vessels. Your doctor may suggest it if other medicines have not helped.

Alternative medicine

Omega-3 fatty acids are a type of unsaturated fatty acid. It’s thought that omega-3 fatty acids can lower inflammation throughout the body. Inflammation has been linked to coronary artery disease. However, the pros and cons of omega-3 fatty acids for heart disease continue to be studied.

Sources of omega-3 fatty acids include:

- Fish and fish oil. Fish and fish oil are the most effective sources of omega-3 fatty acids. Fatty fish — such as salmon, herring and light canned tuna — contain the most omega-3 fatty acids and, therefore, the most benefit. Fish oil supplements may offer benefit, but the evidence is strongest for eating fish.

- Flax and flaxseed oil. Flax and flaxseed oil contain a type of omega-3 fatty acid called alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). ALA contains smaller amounts of omega-3 fatty acids than do fish and fish oil. Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) may help lower cholesterol and improve heart health. But research is mixed. Some studies haven’t found ALA to be as effective as fish. Flaxseed also contains a lot of fiber, which has various health benefits.

- Other oils. Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) can also be found in canola oil, soybeans and soybean oil.

Other supplements may help lower blood pressure or cholesterol — two risk factors for coronary artery disease. Some that may be effective are:

- Barley

- Psyllium, a type of fiber

- Oats, a type of fiber that includes beta-glucans and is found in oatmeal and whole oats

- Garlic

- Plant sterols (found in supplements and some margarines, such as Promise, Smart Balance and Benecol)

Always talk to a health care provider before taking herbs, supplements or medications bought without a prescription. Some drugs and supplements can interfere with other drugs.

Surgery and procedures

If lifestyle changes, medications or other therapies don’t reduce angina pain, a catheter procedure or open-heart surgery may be needed.

Surgeries and procedures used to treat angina and coronary artery disease include:

- Angioplasty with stenting. During an angioplasty — also called a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) — a tiny balloon is inserted into the narrowed artery. The balloon is inflated to widen the artery, and then a small wire mesh coil (stent) is usually inserted to keep the artery open. Angioplasty with stenting improves blood flow in the heart, reducing or eliminating angina. Angioplasty with stenting may be a good treatment option for those with unstable angina or if lifestyle changes and medications don’t effectively treat chronic, stable angina.

- Open-heart surgery (coronary artery bypass surgery [CABG]). During coronary artery bypass surgery, a vein or artery from somewhere else in the body is used to bypass a blocked or narrowed heart artery. Bypass surgery increases blood flow to the heart. It’s a treatment option for both unstable angina and stable angina that has not responded to other treatments.

Having an angioplasty or bypass surgery does not cure coronary heart disease. The aim of these treatments is to improve the blood supply to your heart muscle. This should help to improve your

symptoms, although sometimes it does not get rid of all of them.

Enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP)

Sometimes, a nondrug option called enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) may be recommended to increase blood flow to the heart. With enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP), blood pressure-type cuffs are placed around the calves, thighs and pelvis. EECP requires multiple treatment sessions. EECP may help reduce symptoms in people with frequent, uncontrolled angina (refractory angina).

Spinal cord stimulators

Spinal cord stimulators block the sensation of pain. Emerging research suggests that this technology can help people be more physically active, feel angina less often, and have a better quality of life.

Transmyocardial laser therapy

Transmyocardial laser therapy stimulates growth of new blood vessels or improve blood flow in the heart muscle. It can relieve angina pain and increase your ability to exercise without discomfort. This laser-based treatment is done during open-heart surgery or through cardiac catheterization. Rarely, your doctor may recommend this treatment in combination with coronary artery bypass grafting.

Unstable angina treatment

If you have unstable angina, you may need to check into the hospital to get some rest, have more tests, and prevent complications.

First, your healthcare provider will need to find the blocked part or parts of the coronary arteries by performing a cardiac catheterization or coronary angiography. In this procedure, a catheter is guided through an artery in your arm or leg and into the coronary arteries, then injected with a liquid dye through the catheter. High-speed X-ray movies record the course of the dye as it flows through the arteries, and doctors can identify blockages by tracing the flow. An evaluation of how well your heart is working also can be done during cardiac catheterization.

Next, based on the extent of the coronary artery blockage(s) your doctor will discuss with you the following treatment options:

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants) are used to treat and prevent unstable angina. You will receive these drugs as soon as possible if you can take them safely.

- Antiplatelet agents include aspirin and the prescription drug clopidogrel or something similar (ticagrelor, prasugrel). These medicines may be able to reduce the chance of a heart attack or the severity of a heart attack that occurs. Dual therapy with aspirin and either clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) decreases the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes, acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), cardiovascular death, and stroke 5, 6.

- During an unstable angina event:

- You may get heparin (or another blood thinner) and nitroglycerin (under the tongue or through an IV). Anticoagulants (blood thinners) – reduce mortality by decreasing re-infarction rates in combination with antiplatelet agents. Used intravenously for acute treatment of unstable angina 5.

- Other treatments may include medicines to control blood pressure, anxiety, abnormal heart rhythms, and cholesterol (such as a statin drug).

- A procedure called percutaneous coronary intervention (coronary angioplasty) and stenting can often be done to open a blocked or narrowed coronary artery.