Ascending cholangitis

Ascending cholangitis also known as acute cholangitis, is a bacterial infection superimposed on an obstruction of the biliary tree most commonly from a gallstone, but it may be associated with neoplasm or stricture 1. The classic Charcot’s Triad of findings is right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, fever, and jaundice. A pentad (also known as Reynold’s pentad) can also be seen in which altered mental status and sepsis are present in addition to usual findings. The severity of ascending cholangitis range anywhere from mild infection to life-threatening sepsis caused by the translocation of bacteria into the bloodstream. Thus, therapeutic options for patient management include broad-spectrum antibiotics and, potentially, emergency decompression of the biliary tree 2.

Ascending cholangitis is relatively uncommon. It occurs in association with other diseases that cause biliary obstruction and presence of bacteria in gall bladder bile (bactibilia) (eg, after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), 1-3% of patients develop cholangitis). Risk is increased if dye is injected retrograde.

Gram-negative enteric bacteria, most commonly Escherichia coli, are the primary pathogens 3..

Acute cholangitis is seen in the setting of biliary tree obstruction 4:

- choledocholithiasis (~80%)

- malignancy (~20%)

- sclerosing cholangitis

- biliary tree procedures, e.g. endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

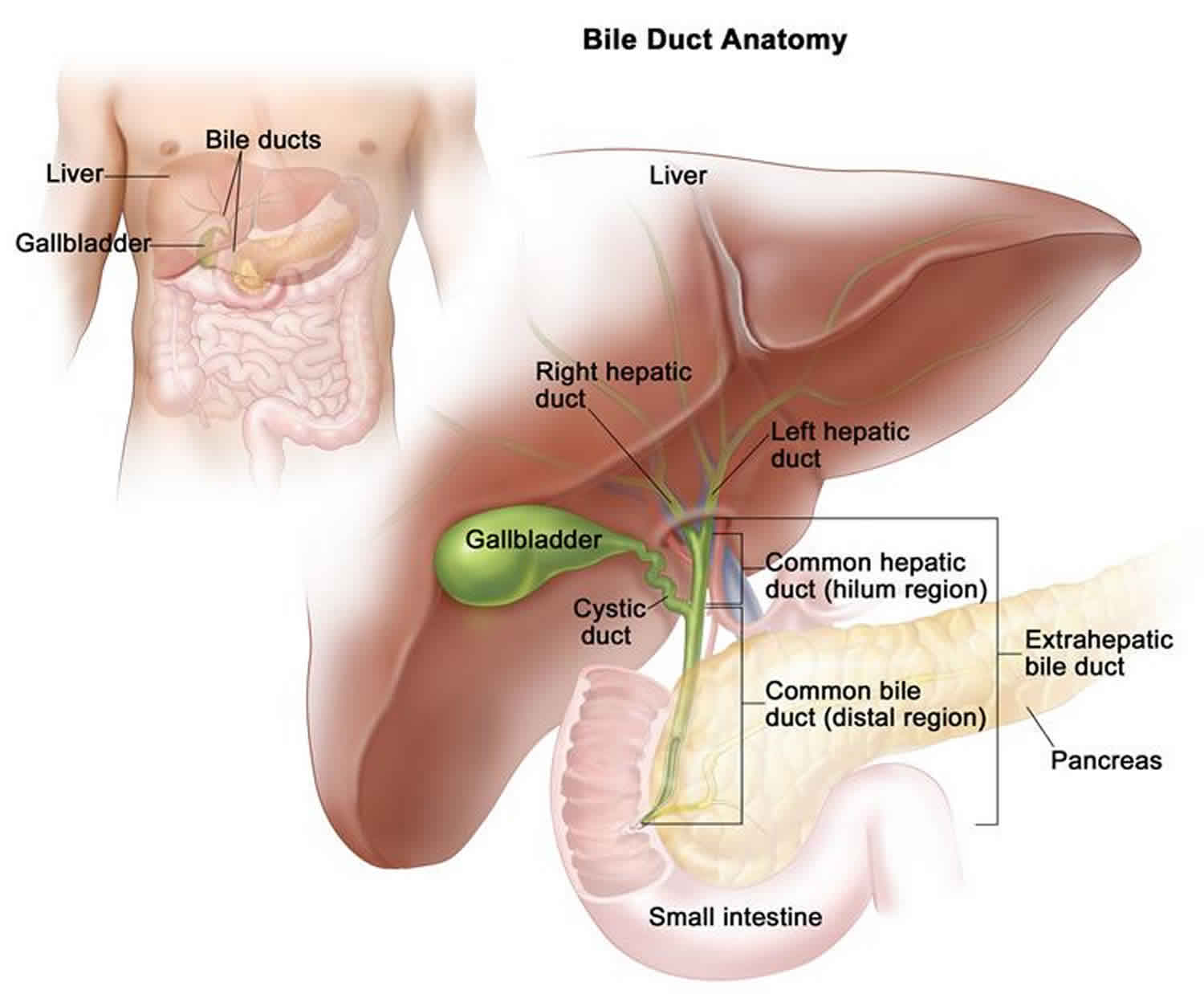

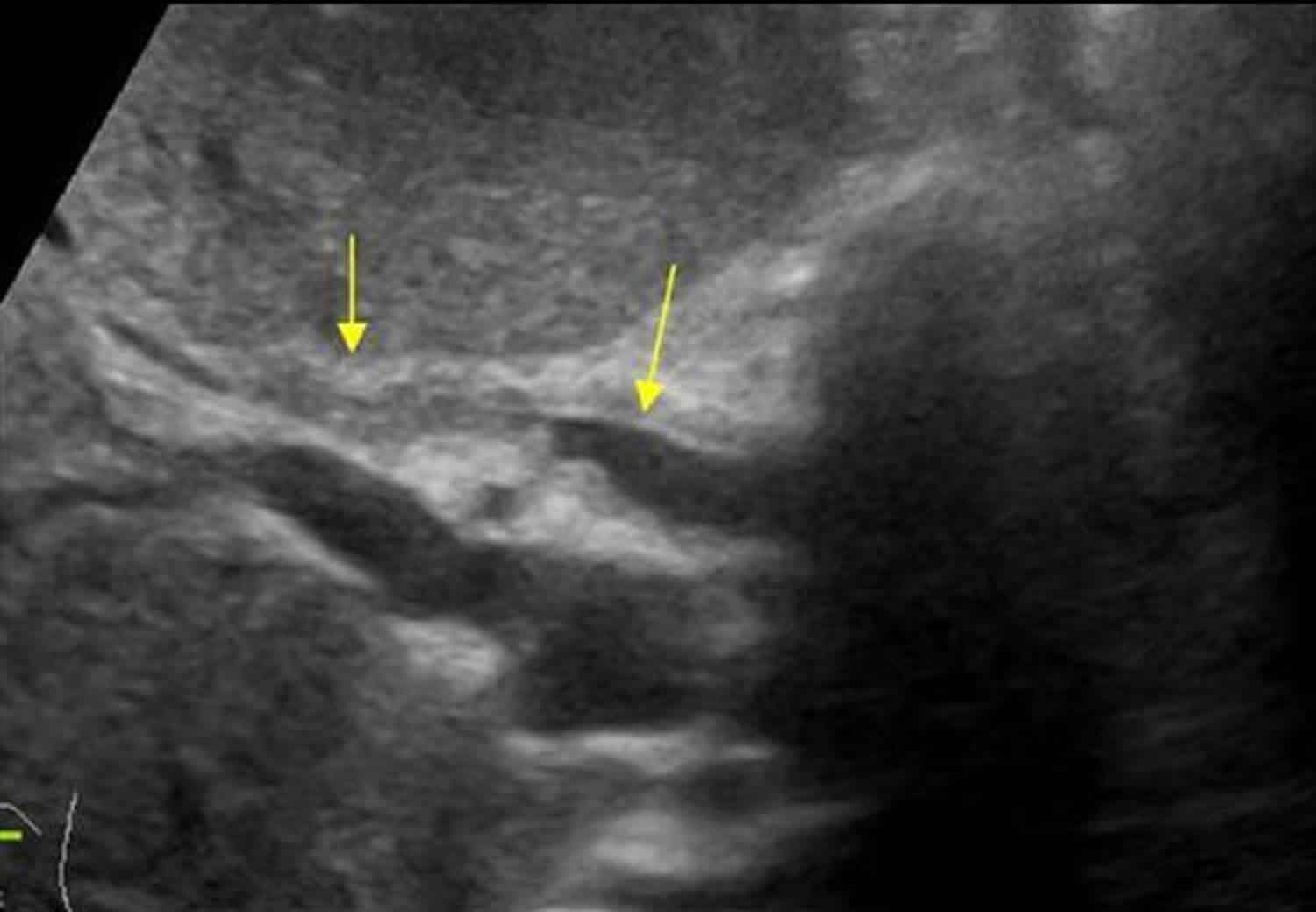

Figure 1. Ascending cholangitis ultrasound

Footnote: 83 year old male presented with fever and and abnormal liver function tests in a patient after cholecystectomy. Cholangitis with segmental narrowing and dilatation of the duct and a thickened wall.

[Source 5 ]Ascending cholangitis causes

In Western countries, gallstones (choledocholithiasis) is the most common cause of ascending cholangitis, followed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and tumors.

Any condition that leads to stasis or obstruction of bile in the common bile duct, including benign or malignant stricture, parasitic infection, or extrinsic compression by the pancreas, can result in bacterial infection and cholangitis. Partial obstruction is associated with a higher rate of infection than complete obstruction.

Common bile duct stones

Common bile duct stones predispose patients to cholangitis. Approximately 10-15% of patients with cholecystitis have common bile duct stones.

Approximately 1% of patients post cholecystectomy have retained common bile duct stones. Most common bile duct stones are immediately symptomatic, while some remain asymptomatic for years.

Some common bile duct stones are formed primarily rather than secondarily to gallstones.

Obstructive tumors

Obstructive tumors cause cholangitis. Partial obstruction is associated with an increased rate of infection compared with that of complete neoplastic obstruction. Obstructive tumors include the following:

- Pancreatic cancer

- Cholangiocarcinoma 6

- Ampullary cancer

- Porta hepatis tumors or metastasis

Other causes

Additional causes of cholangitis include the following:

- Strictures or stenosis

- Endoscopic manipulation of the common bile duct

- Choledochocele

- Sclerosing cholangitis (from biliary sclerosis)

- AIDS cholangiopathy

- Ascaris lumbricoides infections

Ascending cholangitis pathophysiology

The main factors in the pathogenesis of acute ascending cholangitis are biliary tract obstruction, elevated intraluminal pressure, and infection of bile 7. A biliary system that is colonized by bacteria but is unobstructed, typically does not result in cholangitis. It is believed that biliary obstruction diminishes host antibacterial defenses, causes immune dysfunction, and subsequently increases small bowel bacterial colonization. Although the exact mechanism is unclear, it is believed that bacteria gain access to the biliary tree by retrograde ascent from the duodenum or from portal venous blood. As a result, infection ascends into the hepatic ducts, causing serious infection. Increased biliary pressure pushes the infection into the biliary canaliculi, hepatic veins, and perihepatic lymphatics, leading to bacteremia (25-40%). The infection can be suppurative in the biliary tract.

The bile is normally sterile. In the presence of gallbladder or common duct stones, however, the incidence of bactibilia increases. The most common organisms isolated in bile are Escherichia coli (27%), Klebsiella species (16%), Enterococcus species (15%), Streptococcus species (8%), Enterobacter species (7%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7%). Organisms isolated from blood cultures are similar to those found in the bile. The most common pathogens isolated in blood cultures are E coli (59%), Klebsiella species (16%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5%), and Enterococcus species (4%). In addition, polymicrobial infection is commonly found in bile cultures (30-87%) and less frequent in blood cultures (6-16%).

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic liver disease that is thought to be due to an autoimmune mechanism 8. It is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. This condition ultimately leads to portal hypertension and cirrhosis of the liver with the only definitive treatment being a liver transplant 9.

Ascending cholangitis prevention

Prophylactic antibiotics prior to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may decrease risk of cholangitis.

Prompt recognition and treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis in patients at higher risk for complications (eg, those with diabetes) decrease risk of cholangitis.

Aggressive search for commond bile duct stones during diagnosis and treatment of cholecystitis may be necessary to prevent cholangitis.

Ascending cholangitis symptoms

Charcot described cholangitis as a triad of findings of right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain, fever, and jaundice. The Reynolds pentad adds mental status changes and sepsis to the triad. A spectrum of cholangitis exists, ranging from mild symptoms to fulminant overwhelming sepsis. With septic shock, the diagnosis can be missed in up to 25% of patients.

Consider acute ascending cholangitis in any patient who appears septic, especially in patients who are elderly, jaundiced, or who have abdominal pain. A history of abdominal pain or symptoms of gallbladder colic may be a clue to the diagnosis.

Acute ascending cholangitis symptoms include the following:

- Charcot’s triad consists of fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice. It is reported in up to 50-70% of patients with cholangitis. However, recent studies believe it is more likely to be present in 15-20% of patients.

- Fever is present in approximately 90% of cases.

- Abdominal pain and jaundice is thought to occur in 70% and 60% of patients, respectively.

- Patients present with altered mental status 10-20% of the time and hypotension approximately 30% of the time. These signs, combined with Charcot’s triad, constitute Reynolds pentad.

- Consequently, many patients with ascending cholangitis do not present with the classic signs and symptoms 10.

- Most patients complain of right upper quadrant pain; however, some patients (ie, elderly persons) are too ill to localize the source of infection.

Other symptoms include the following:

- Jaundice

- Fever, chills, and rigors

- Abdominal pain

- Pruritus

- Acholic or hypocholic stools

- Malaise

The patient’s medical history may be helpful. For example, a history of the following increases the risk of cholangitis:

- Gallstones, common bile duct stones

- Recent cholecystectomy

- Endoscopic manipulation or ERCP, cholangiogram

- History of cholangitis

- History of HIV or AIDS: AIDS-related cholangitis is characterized by extrahepatic biliary edema, ulceration, and obstruction. The etiology is uncertain, but it may be related to cytomegalovirus or Cryptosporidium infections. The management of this condition is described below, although decompression is usually not necessary.

In general, patients with acute ascending cholangitis are quite ill and frequently present in septic shock without an apparent source of the infection.

Physical examination may reveal the following:

- Fever (90%), although elderly patients may have no fever

- Right upper quadrant (RUQ) tenderness (65%)

- Mild hepatomegaly

- Jaundice (60%)

- Mental status changes (10-20%)

- Sepsis

- Hypotension (30%)

- Tachycardia

- Peritonitis (uncommon, and should lead to a search for an alternative diagnosis)

Ascending cholangitis complications

Patients are increasingly likely to have complications with greater degrees of illness, as follows:

- Liver failure, hepatic abscesses, and microabscesses

- Bacteremia (25-40%); gram-negative sepsis

- Acute renal failure

Catheter-related problems in patients treated with percutaneous or endoscopic drainage include the following:

- Bleeding (intra-abdominally or percutaneously)

- Catheter-related sepsis

- Fistulae

- Bile leak (intraperitoneally or percutaneously)

Ascending cholangitis diagnosis

You may have the following tests to look for blockages:

- Abdominal ultrasound

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram (PTCA)

You may also have the following blood tests:

- Bilirubin level

- Liver enzyme levels

- Liver function tests

- White blood count (WBC)

Procalcitonin may have potential as a useful biomarker for determining the need for emergency biliary drainage and intensive care in patients with acute cholangitis 11. Shinya et al 11 noted that significantly elevated procalcitonin levels were found in their cohort of patients with grade III inflammation based on the 2013 Tokyo guidelines versus those with grade I inflammation, as well as those with positive hemocultures compared to those with negative hemocultures. Moreover, procalcitonin levels were significantly increased in severe cases that were underestimated as grade I or II 11.

Imaging studies are important to confirm the presence and cause of biliary obstruction and to rule out other conditions 2. Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scanning are the most commonly used first-line imaging modalities. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and endoscopic ultrasonography are commonly used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes 2.

Abdominal ultrasound

Ultrasonography is excellent for gallstones and cholecystitis 12. It is highly sensitive and specific for examining the gallbladder and assessing bile duct dilatation (see the following image). However, it often misses stones in the distal bile duct 13.

Consider the following:

- Transabdominal ultrasonography is the initial imaging study of choice.

- Ultrasonography can differentiate intrahepatic obstruction from extrahepatic obstruction and image dilated ducts.

- In one study of cholangitis, only 13% of common bile duct stones were observed on ultrasonography, but dilated common bile duct was found in 64%.

- Advantages to sonography include the ability to be performed rapidly at the bedside by the emergency department physician, capacity to image other structures (eg, aorta, pancreas, liver), identification of complications (eg, perforation, empyema, abscess), and lack of radiation.

- Disadvantages to sonography include operator and patient dependence, cannot image the cystic duct, and decreased sensitivity for distal common bile duct stones.

- A normal sonogram does not rule out acute cholangitis.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is both diagnostic and therapeutic and is considered the criterion standard for imaging the biliary system.

ERCP should be reserved for patients who may require therapeutic intervention. Patients with a high clinical suspicion for cholangitis should proceed directly to ERCP.

ERCP has a high success rate (98%) and is considered safer than surgical and percutaneous intervention.

Diagnostic use of ERCP carries a complication rate of approximately 1.38% and a mortality rate of 0.21%. The major complication rate of therapeutic ERCP is 5.4%, and it has a mortality rate of 0.49%. Complications include pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation 14.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a noninvasive imaging modality that is increasingly being used in the diagnosis of biliary stones and other biliary pathology.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is accurate for detecting choledocholithiasis, neoplasms, strictures, and dilations within the biliary system.

Limitations of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography include the inability for invasive diagnostic tests such as bile sampling, cytologic testing, stone removal, or stenting. It has limited sensitivity for small stones (< 6 mm in diameter).

Absolute contraindications are the same as for a traditional MRI, which include the presence of a cardiac pacemaker, cerebral aneurysm clips, ocular or cochlear implants, and ocular foreign bodies. Relative contraindications include the presence of cardiac prosthetic valves, neurostimulators, metal prostheses, and penile implants.

The risk of MRCP during pregnancy is not known.

Ascending cholangitis treatment

In unstable patients with acute ascending cholangitis, prehospital care should include the following:

- Immediate assessment of ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation)

- Monitoring (eg, pulse oximetry, cardiac monitor, frequent blood pressure measurements, blood glucose measurement)

- Stabilization (eg, oxygen, placement of 2 large-bore IVs, administration of IV fluids to unstable patients)

- Rapid transport

Emergency department care

Suspect mild cholangitis in patients with jaundice and a fever; consider cholangitis in all patients with sepsis.

The degree of urgency of treatment depends on severity of illness. Important points are resuscitation, diagnosis, and treatment.

Management of acute cholangitis in the emergency department includes the following:

- After assessment of the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), place the patient on a monitor with pulse oximetry, provide oxygen via nasal canula, and obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG). Draw and send laboratory studies (including blood cultures) when the intravenous line is placed.

- Provide fluid resuscitation with intravenous (IV) crystalloid solution (eg, 0.9% normal saline).

- Administer parenteral antibiotics empirically after blood cultures are drawn. Do not delay administration of antibiotics if blood cultures cannot be drawn.

- Correct any electrolyte abnormalities or coagulopathies.

- Standard therapy for cholangitis consists of broad-spectrum antibiotics with close observation to determine the need for emergency decompression of the biliary tree 15.

- A nasogastric tube may be helpful for patients who are vomiting.

- Patients should be nothing by mouth (NPO). Place a Foley catheter in ill patients to monitor urine output.

The surgical literature states that, in patients with mild cholangitis, 80-90% respond to medical therapy 16. Approximately 15% do not respond and subsequently require immediate surgical or endoscopic decompression. Mortality rates approach 100% for patients who fail medical therapy and do not have surgical decompression.

In severely ill patients, treatment is immediate biliary decompression. The method depends on the degree of illness. In the past, drainage was performed surgically. Today, options of percutaneous or endoscopic drainage exist in addition to medical management with antibiotics. Endoscopic drainage has been shown to decrease mortality rates from 30% to 10%.

Zhang et al indicate that endoscopic sphincterotomy is safe and effective for temporary biliary decompression in patients with acute obstructive cholangitis, and endoscopic nasobiliary drainage without sphincterotomy may be considered as a first-line therapy in this setting 17. The investigators also suggested that endoscopic sphincterotomy may improve the effectiveness of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage in those with papillary inflammation stricture and thick bile.

Medical therapy can be complementary to surgical or endoscopic treatments. In less ill patients, medical treatment may be all that is necessary. Perform the following:

- The mainstay of medical therapy is drainage. ERCP is the best method to accomplish biliary drainage. A study by Sharma showed equal safety and effectiveness when using a 7 Fr stent or 10 Fr stent for biliary drainage in patients with severe cholangitis 18.

- Maintain medical therapy and consider elective surgery with patients who show improvement. Patients who are being medically managed and do not improve or who deteriorate should rapidly be referred to undergo either endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), sphincterotomy, or percutaneous drainage 12.

Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage is a technique that is being used in Asia in the surgical management of acute cholangitis 19. Data from a meta-analysis indicate that endoscopic nasobiliary drainage may cause fewer perioperative complications (eg, preoperative cholangitis rate, postoperative pancreatic fistula rate) than endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS) in patients with malignant biliary obstruction 20. However, a limitation of the meta-analysis was that there were no data from randomized controlled trials.

Admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for ill patients is appropriate. Continue intravenous antibiotics; monitor the blood cultures so that the antibiotics can be narrowed to the appropriate pathogen, and provide supportive measures including administration of intravenous fluids 15. Administer intravenous antibiotics 12-24 hours prior to nonemergent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Refer worsening patients to emergent ERCP for sphincterotomy or percutaneous drainage.

Traditionally, antibiotics were administered for 7-10 days to treat cholangitis. However, it now appears that a 3-day course may be sufficient in patients who undergo adequate biliary drainage.

In addition, a study by Park et al 21 indicated that in patients with acute cholangitis with bacteremia who have achieved successful biliary drainage, treatment with an early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics is just as effective as conventional 10-day intravenous antibiotic therapy. The study involved 59 patients, including 30 who underwent conventional intravenous antibiotic treatment and 29 who were switched early in treatment to oral antibiotics. At follow-up, 30 days after diagnosis, the investigators determined that the bacterial eradication rate was not significantly different between the two groups, being 93.3% for the conventional treatment patients and 93.1% for the early switch group. Moreover, the groups showed no statistically significant differences in the recurrence rate for acute cholangitis and the 30-day mortality rate.

Ascending cholangitis prognosis

Acute ascending cholangitis prognosis depends on several factors, including the following 22:

- Early recognition and treatment of cholangitis

- Response to therapy

- Underlying medical conditions of the patient

Mortality rate ranges from 5-10%, with a higher mortality rate in patients who require emergency decompression or surgery. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for acute cholangitis within 24 hours appears to be associated with a lower 30-day mortality 23.

In patients responding to antibiotic therapy, the prognosis is good.

Schneider et al 24 proposed a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality in patients with acute cholangitis using 22 predictors and the Tokyo criteria to stratify them into high- and low-risk mortality groups and then into different management groups. In univariate analysis, organ failure had the strongest association with mortality—with mental confusion, hypotension requiring catecholamines, Quick value below 50%, serum creatinine level above 2 mg/dL, and a platelet count below 100,000/mm3 as prognostic factors contributing to organ failure. Patients classified as low risk for mortality would be considered for elective biliary drainage, whereas those considered to be at high risk for mortality would undergo urgent biliary drainage 24.

Schwed et al 25 indicate that leukocytosis greater than 20,000 cells/μL and total bilirubin level above 10 mg/dL, but not timing of ERCP, are independent prognostic factors for adverse outcomes. In a separate study, Tabibian et al 26 did not find adverse outcomes from weekend admission and weekend endoscopic retrograde cholangiography on patients with acute cholangitis admitted to a tertiary care center.

Morbidity and mortality

Mortality from cholangitis is high due to the predisposition in people with underlying disease. Historically, the mortality rate was 100%. With the advent of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, therapeutic endoscopic sphincterotomy, stone extraction, and biliary stenting, the mortality rate has significantly declined to approximately 5-10%.

The following patient characteristics are associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates:

- Hypotension

- Acute renal failure

- Liver abscess

- Cirrhosis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- High malignant strictures

- Radiologic cholangitis: Post percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

- Female gender

- Age older than 50 years

- Failure to respond to antibiotics and conservative therapy

Advanced age, concurrent medical problems, and delay in decompression increase the emergent operative mortality rate (17-40%).

The mortality rate of elective surgery after medical stabilization is significantly less (approximately 3%).

In the past, suppurative cholangitis was thought to have increased morbidity; however, prospective studies have not found this to be true.

References- Acute Cholangitis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/774245-overview

- Mohammad Alizadeh AH. Cholangitis: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017 Dec 28. 5 (4):404-13.

- Emergency Radiology. Springer. (2007) ISBN:3540689087

- Kim SW, Shin HC, Kim HC et-al. Diagnostic performance of multidetector CT for acute cholangitis: evaluation of a CT scoring method. Br J Radiol. 2012;85 (1014): 770-7. doi:10.1259/bjr/72001875

- Cholangitis. https://www.ultrasoundcases.info/cholangitis-4958/

- Jabara B, Fargen KM, Beech S, Slakey DR. Diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma: a case series and literature review. J La State Med Soc. 2009 Mar-Apr. 161(2):89-94.

- Ascending cholangitis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/774245-overview

- Aron JH, Bowlus CL. The immunobiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009 Sep. 31(3):383-97.

- Kashyap R, Mantry P, Sharma R, et al. Comparative analysis of outcomes in living and deceased donor liver transplants for primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009 Aug. 13(8):1480-6.

- Kinney TP. Management of ascending cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007 Apr. 17(2):289-306, vi.

- Shinya S, Sasaki T, Yamashita Y, et al. Procalcitonin as a useful biomarker for determining the need to perform emergency biliary drainage in cases of acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014 Oct. 21 (10):777-85.

- Cremer A, Arvanitakis M. Diagnosis and management of bile stone disease and its complications. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2016 Mar. 62 (1):103-29.

- Rustemovic N, Cukovic-Cavka S, Opacic M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound elastography as a method for screening the patients with suspected primary sclerosing cholangitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Jun. 22(6):748-53.

- Iorgulescu A, Sandu I, Turcu F, Iordache N. Post-ERCP acute pancreatitis and its risk factors. J Med Life. 2013 Mar 15. 6(1):109-13.

- Wilkins T, Agabin E, Varghese J, Talukder A. Gallbladder dysfunction: cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and biliary dyskinesia. Prim Care. 2017 Dec. 44 (4):575-97.

- van Erpecum KJ. Gallstone disease. Complications of bile-duct stones: Acute cholangitis and pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006. 20(6):1139-52.

- Zhang RL, Zhao H, Dai YM, et al. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage with sphincterotomy in acute obstructive cholangitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Dig Dis. 2014 Feb. 15 (2):78-84.

- Sharma BC, Agarwal N, Sharma P, Sarin SK. Endoscopic biliary drainage by 7 Fr or 10 Fr stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 Jun. 54(6):1355-9.

- Itoi T, Kawai T, Sofuni A, et al. Efficacy and safety of 1-step transnasal endoscopic nasobiliary drainage for the treatment of acute cholangitis in patients with previous endoscopic sphincterotomy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Jul. 68(1):84-90.

- Lin H, Li S, Liu X. The safety and efficacy of nasobiliary drainage versus biliary stenting in malignant biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Nov. 95 (46):e5253.

- Park TY, Choi JS, Song TJ, et al. Early oral antibiotic switch compared with conventional intravenous antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis with bacteremia. Dig Dis Sci. 2014 Nov. 59(11):2790-6.

- Rosing DK, De Virgilio C, Nguyen AT, El Masry M, Kaji AH, Stabile BE. Cholangitis: analysis of admission prognostic indicators and outcomes. Am Surg. 2007 Oct. 73(10):949-54.

- Tan M, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Laursen SB. Association between early ERCP and mortality in patients with acute cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Jan. 87 (1):185-92.

- Schneider J, Hapfelmeier A, Thores S, et al. Mortality risk for acute cholangitis (MAC): a risk prediction model for in-hospital mortality in patients with acute cholangitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 9. 16:15.

- Schwed AC, Boggs MM, Pham XD, et al. Association of admission laboratory values and the timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with clinical outcomes in acute cholangitis. JAMA Surg. 2016 Nov 1. 151 (11):1039-45.

- Tabibian JH, Yang JD, Baron TH, Kane SV, Enders FB, Gostout CJ. Weekend admission for acute cholangitis does not adversely impact clinical or endoscopic outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2016 Jan. 61 (1):53-61.