What is bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis is a common infection of the vagina when there is too much of certain bacteria in the vagina, with a loss of protective lactic-acid producing Lactobacillus species in conjunction with increases in the concentration of facultative and strict anaerobic bacteria including Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella spp., Atopobium vaginae, Sneathia spp., and other bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria 1. Bacterial vaginosis can increase your risk of acquiring a number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV 2. In addition, bacterial vaginosis may contribute to adverse birth outcomes, such as premature birth, low birth weight, and premature rupture of membranes 3. Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of vaginal discharge and vaginal infection in women ages 15-44, but any woman can get bacterial vaginosis 4. The estimated prevalence of bacterial vaginosis among reproductive-aged women in the United States has ranged from a low of 17% to a high of 47%, with an overall estimated prevalence of approximately 25 to 30% 4, 5. In these studies, many of the women with bacterial vaginosis were asymptomatic. Data on the incidence of bacterial vaginosis are extremely limited.

Although the actual cause of bacterial vaginosis is currently unknown, scientists believed bacterial vaginosis is linked to an imbalance of “good” and “harmful” bacteria that are normally found in a woman’s vagina, which could be caused by certain activities that increase your risk, such as unprotected sex or frequent douching. Increased bacterial vaginosis prevalence is associated with a greater number of male sex partners, sex with a female partner, douching and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection 6, 7. A reduced risk is associated with condom use, male partners who are circumcised, and oral contraceptive pills 8, 9. Increasing evidence suggests that sexual activity is integral to the development of incident bacterial vaginosis in most persons, as it correlates with the frequency of sexual activity, younger age at sexual debut, participating in anal and oral sex, and use of vaginal sex toys 10, 5. The role of sexual activity in bacterial vaginosis is also supported by indirect evidence, including (1) the absence of bacterial vaginosis in women prior to sexual debut, (2) concordant vaginal flora among women in same-sex partnerships, and (3) elevated rates of bacterial vaginosis-associated bacterial colonization (as measured with penile swabs) among men engaging in extramarital sexual relationships, as compared with men who are monogamous 11, 12.

Bacterial vaginosis is harmless and easily treated. Bacterial vaginosis is not classed as a sexually transmitted infection (STI) or sexually transmitted disease (STD). However, having bacterial vaginosis can increase your chance of getting a STD (e.g., HIV, N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and HSV- 2) including developing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Bacterial vaginosis also increases the risk for HIV transmission to male sex partners 13. Although bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria can be found in the male genitalia, treatment of male sex partners has not been beneficial in preventing the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis 14.

Please note, bacterial vaginosis must not be confused with vaginitis (inflammation of the vagina). Vaginitis is defined as any condition with symptoms of abnormal vaginal discharge, odor, irritation, itching, or burning 15. The most common causes of vaginitis are bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis 15. Bacterial vaginosis is implicated in 40% to 50% of vaginitis cases when a cause is identified, with vulvovaginal candidiasis accounting for 20% to 25% and trichomoniasis for 15% to 20% of cases. Noninfectious causes, including atrophic, irritant, allergic, and inflammatory vaginitis, are less common and account for 5% to 10% of vaginitis cases. Most women have at least one episode of vaginitis during their lives, making it the most common gynecologic diagnosis in primary care 15.

Bacterial vaginosis key facts

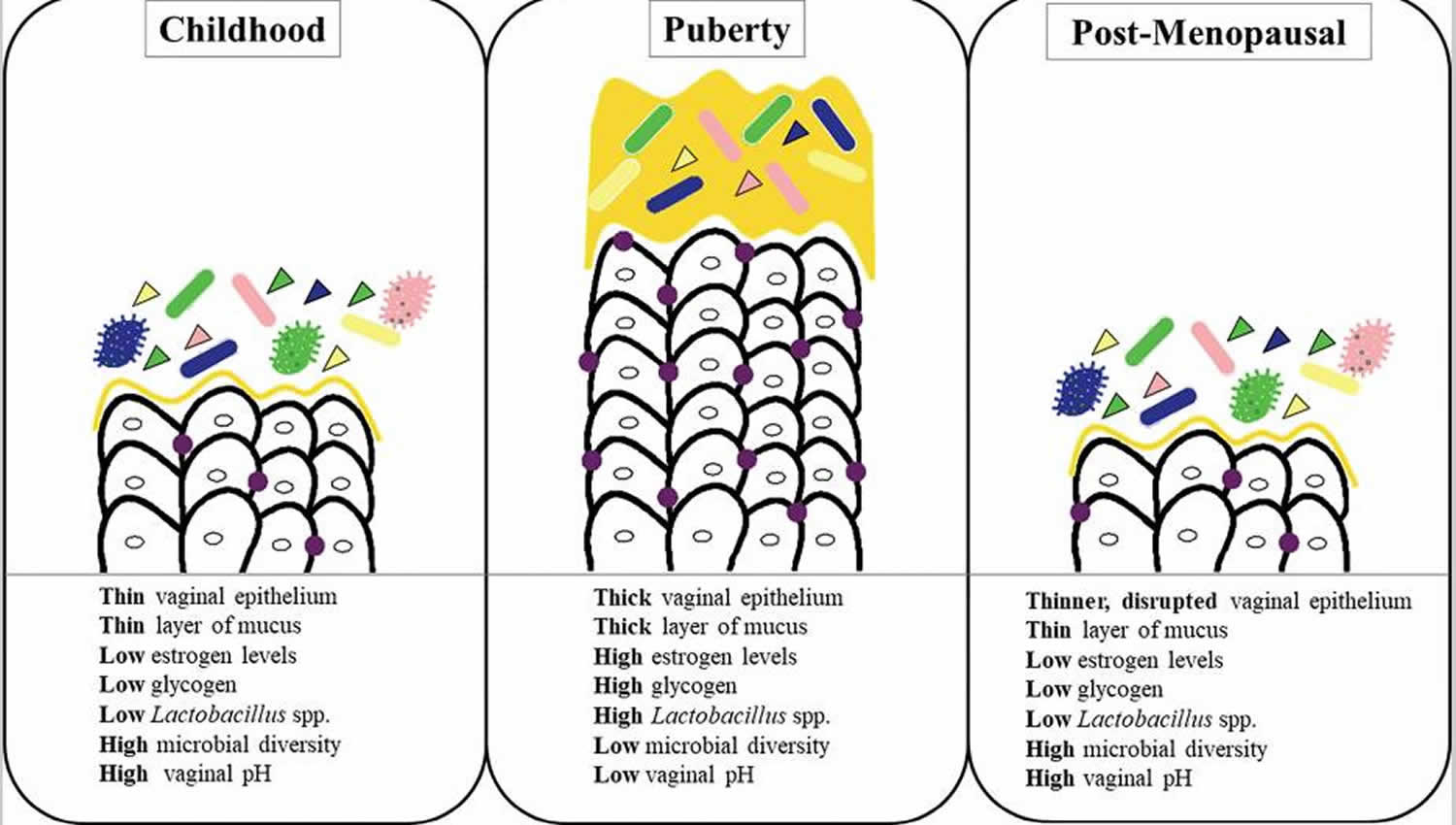

- The vagina is a dynamic ecosystem that changes with age (see Figure 1). Under normal conditions, 70-90% of the vaginal bacterial species in healthy premenopausal women are Lactobacilli 16. Among more than 200 Lactobacillus species, over 20 species have been found in the vaginal flora 17. Sequencing of the 16 rRNA gene revealed that the vaginal bacterial community, mainly composed of Lactobacilli, is classified into five groups named community state types (CST), namely I, II, III, IV and V 18. Four of these groups are dominated by Lactobacillus. The first is dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus, the second by Lactobacillus gasseri, the third by Lactobacillus iners, and the fifth by Lactobacillus jensenii, while the fourth contains a smaller proportion of Lactobacilli but is composed of a polymicrobial mixture of strict and facultative anaerobes (Gardnerella, Atopobium, Mobiluncus, Prevotella…) 19.

- Normal vaginal discharge is clear to white, odorless, and of high viscosity. The normal bacterial microbiota is dominated by Lactobacillus spp. (i.e. Lactobacillus crispatus), but a variety of other facultative and strict anaerobic bacteria are also present at much lower levels. Lactobacillus species are a major part of the lactic acid bacteria group (i.e. they convert sugars to lactic acid) in your vagina, which helps to maintain a normal acidic vaginal pH of 3.8 to 4.5. Some lactobacilli produce H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide), which serves as a host defense mechanism and kills bacteria and viruses. Lactobacillus is a genus of Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic or microaerophilic, rod-shaped, non-spore-forming bacteria. Usually, “good” bacteria (lactobacilli) outnumber “bad” bacteria (anaerobes). But if there are too many anaerobic bacteria, they upset the natural balance of microorganisms in your vagina and cause bacterial vaginosis.

- Bacterial vaginosis is the most common vaginal condition in women ages 15 to 44 20. But women of any age can get it, even if they have never had sex.

- Researchers are still studying how women get bacterial vaginosis. You can get bacterial vaginosis without having sex, but bacterial vaginosis is more common in women who are sexually active. Having a new sex partner or multiple sex partners, as well as douching, can upset the balance of good and harmful bacteria in your vagina 20. This raises your risk of getting bacterial vaginosis.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends all women with bacterial vaginosis should be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) 21.

- Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of vaginal symptoms among women, but it is not clear what role sexual activity plays in the development of bacterial vaginosis.

- You may be more at risk for bacterial vaginosis if you:

- Have a new sex partner

- Have multiple sex partners

- Douche 22

- Do not use condoms or dental dams

- Are pregnant. bacterial vaginosis is common during pregnancy. About 1 in 4 pregnant women get bacterial vaginosis 23. The risk for bacterial vaginosis is higher for pregnant women because of the hormonal changes that happen during pregnancy.

- Are African-American. bacterial vaginosis is twice as common in African-American women as in white women 24

- Have an intrauterine device (IUD), especially if you also have irregular bleeding 25

- Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy has been linked to several obstetric complications, including late miscarriage, premature rupture of membranes, premature delivery, and low birth weight at delivery 3, 26, 27, 28. Bacterial vaginosis has also been associated with gynecologic complications, particularly an increased risk of post-operation infections after gynecological procedures 29. There are some data to suggest bacterial vaginosis may cause additional gynecologic complications, including endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and infertility, but prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to conclusively determine if bacterial vaginosis clearly causes these complications 30.

The prevalence in the United States is estimated to be 21.2 million (29.2%) among women ages 14–49, based on a nationally representative sample of women who participated in NHANES 2001–2004. The following are other findings from this study 31.

- Most women found to have bacterial vaginosis (84%) reported no symptoms.

- Women who have not had vaginal, oral, or anal sex can still be affected by bacterial vaginosis (18.8%), as can pregnant women (25%), and women who have ever been pregnant (31.7%).

- Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis increases based on lifetime number of sexual partners.

- Non white women have higher rates (African-American 51%, Mexican Americans 32%) than white women (23%).

Bacterial vaginosis is traditionally diagnosed with Amsel criteria, although Gram stain is the diagnostic standard 15.

Bacterial vaginosis is treated with oral metronidazole, intravaginal metronidazole, or intravaginal clindamycin 15. Treatment is especially important for pregnant women. Pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis may deliver premature (early) or low birth-weight babies.

Recommended antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis 21:

- Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

- OR Metronidazole gel 0.75%, one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally, once a day for 5 days

- OR Clindamycin cream 2%, one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days

Alcohol consumption should be avoided during treatment with nitroimidazoles. To reduce the possibility of a disulfiram-like reaction, abstinence from alcohol use should continue for 24 hours after completion of metronidazole. Clindamycin cream is oil-based and might weaken latex condoms and diaphragms for 5 days after use (refer to clindamycin product information for additional information).

Women should be advised to refrain from sexual activity or use condoms consistently and correctly during the treatment regimen. Douching might increase the risk for relapse, and no data support the use of douching for treatment or relief of symptoms.

You can buy treatments for bacterial vaginosis over the counter, but there’s no clear proof they work.

Figure 1. Vaginal microbiome over a woman’s lifespan

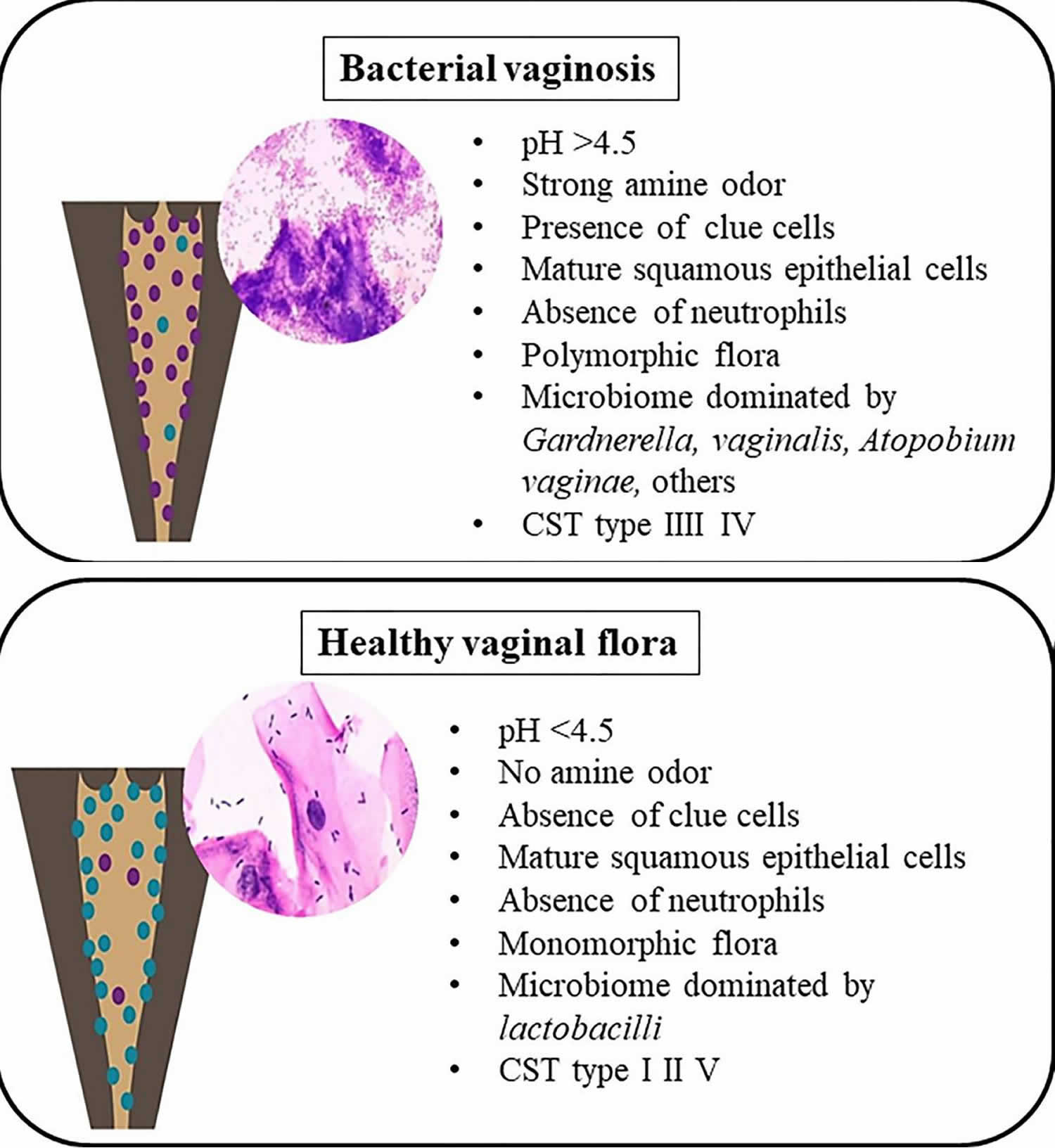

[Source 32 ]Figure 2. Bacterial vaginosis versus healthy vaginal flora

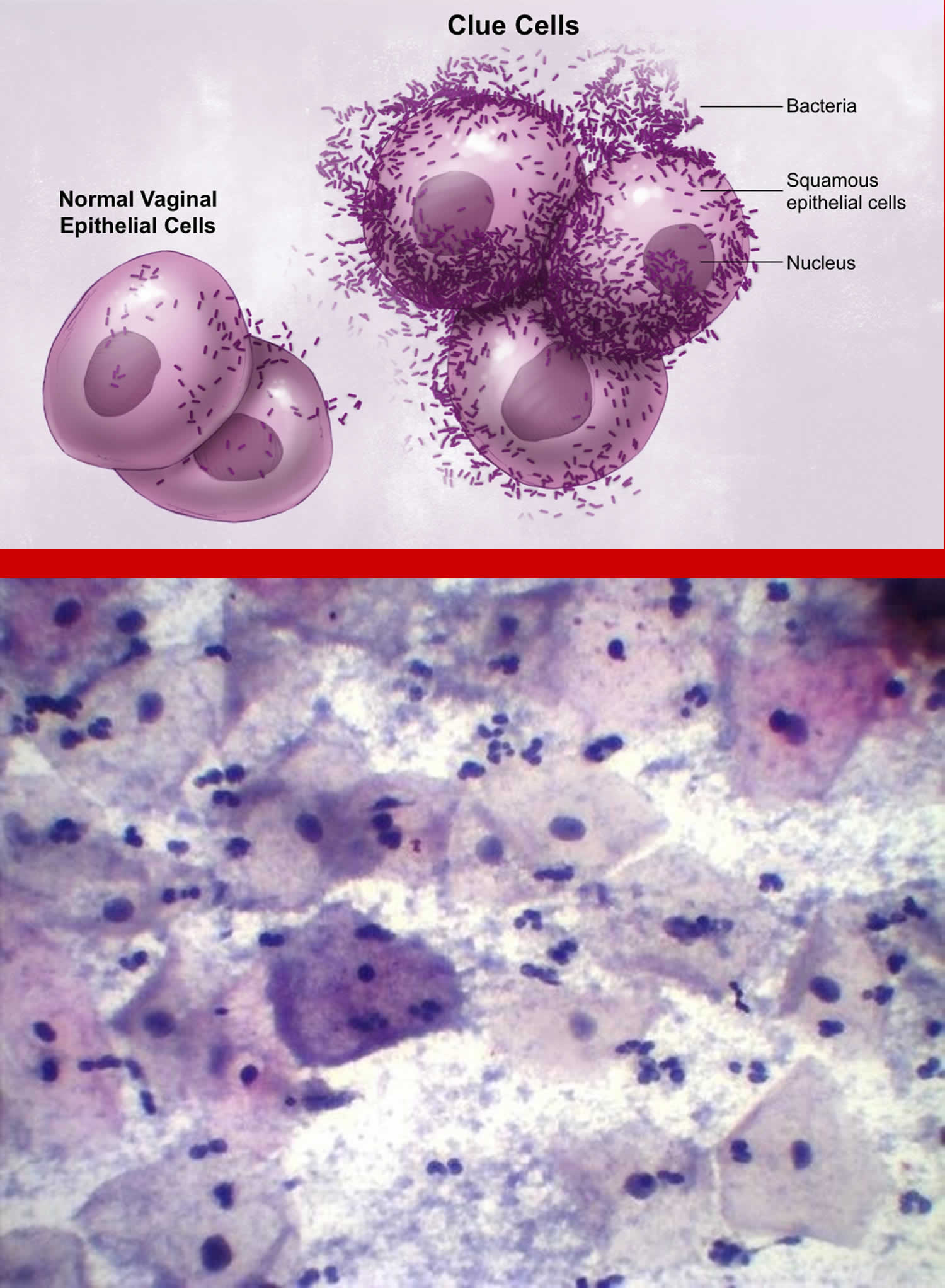

[Source 32 ]Figure 3. Bacterial vaginosis clue cells (vaginal cells covered with bacteria that are a sign of bacterial vaginosis)

[Source 33 ]Home remedies for bacterial vaginosis

To help relieve symptoms and prevent bacterial vaginosis from returning:

DO

- use water and an emollient, such as E45 cream, or plain soap to wash your genital area

- have showers instead of baths

- stay out of hot tubs or whirlpool baths.

- wash your vagina and anus with a gentle, non-deodorant soap.

- rinse completely and gently dry your genitals well.

- use unscented tampons or pads.

- wear loose-fitting clothing and cotton underwear. Avoid wearing pantyhose.

- wipe from front to back after you use the bathroom.

DON’T

- use perfumed soaps, bubble bath or shower gel

- use vaginal deodorants, washes or douches

- put antiseptic liquids in the bath

- use strong detergents to wash your underwear

- smoke

See a doctor or sexual health clinic if:

- You have vaginal discharge that’s new and associated with an odor or fever. Your doctor can help determine the cause and identify signs and symptoms.

- You’ve had vaginal infections before, but the color and consistency of your discharge seems different this time.

- You have multiple sex partners or a recent new partner. Sometimes, the signs and symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection are similar to those of bacterial vaginosis.

- You try self-treatment for a yeast infection with an over-the-counter treatment and your symptoms persist.

- Your vaginal discharge has a strong fishy smell, particularly after sex

- Your vaginal discharge is white or grey

- Your vaginal discharge is thin and watery

Bacterial vaginosis doesn’t usually cause any soreness or itching. If you’re unsure it’s bacterial vaginosis check vaginal discharge.

| Vaginal Discharge | Possible cause |

|---|---|

| Smells fishy | bacterial vaginosis |

| Thick and white, like cottage cheese | thrush |

| Green, yellow or frothy | trichomoniasis |

| With pelvic pain or bleeding | chlamydia or gonorrhoea |

| With blisters or sores | genital herpes |

Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis requires a vaginal exam by a qualified health care provider and the laboratory testing of fluid collected from the vagina 34.

An examination to diagnose bacterial vaginosis is similar to a regular gynecological checkup. While performing the examination, your doctor will visually examine your vagina for signs of bacterial vaginosis, which include increased vaginal discharge that has a white or gray color.

Your health care provider will also collect a small amount of your vaginal fluid with a wooden spatula or cotton-tipped applicator. The sample will be tested in a laboratory for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis.

An accurate diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is important because it will help the provider determine whether you have bacterial vaginosis or some other infection, such as a sexually transmitted disease like chlamydia or gonorrhoea. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends all women with bacterial vaginosis should be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) 21.

If bacterial vaginosis is diagnosed in a sexually active woman, she should be tested for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as:

- Syphilis

- Gonorrhea

- Chlamydia

- Hepatitis B

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

How do you get bacterial vaginosis?

Researchers do not know the cause of bacterial vaginosis or how some women get it. Scientists do know that the infection typically occurs in sexually active women. Bacterial vaginosis is linked to an imbalance of “good” and “harmful” bacteria that are normally found in a woman’s vagina. Having a new sex partner or multiple sex partners, as well as douching, can upset the balance of bacteria in the vagina. This places a woman at increased risk for getting bacterial vaginosis.

Researchers also do not know how sex contributes to bacterial vaginosis. There is no research to show that treating a sex partner affects whether or not a woman gets bacterial vaginosis. Having bacterial vaginosis can increase your chances of getting other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Bacterial vaginosis rarely affects women who have never had sex.

You cannot get bacterial vaginosis from toilet seats, bedding, or swimming pools.

How can I avoid getting bacterial vaginosis?

Doctors and scientists do not completely understand how bacterial vaginosis spreads. There are no known best ways to prevent it.

The following basic prevention steps may help lower your risk of developing bacterial vaginosis:

- Not having sex;

- Limiting your number of sex partners;

- Always using a condom when you have sex; and

- Not douching. Douching removes the healthy bacteria in your vagina that protect against infection.

How do I know if I have bacterial vaginosis?

Many women with bacterial vaginosis do not have symptoms. If you do have symptoms, you may notice:

- A thin white or gray vaginal discharge;

- Pain, itching, or burning in the vagina;

- A strong fish-like odor, especially after sex;

- Burning when urinating;

- Itching around the outside of the vagina.

How will my doctor know if I have bacterial vaginosis?

A health care provider will examine your vagina for signs of vaginal discharge. Your provider can also perform laboratory tests on a sample of vaginal fluid to determine if bacterial vaginosis is present. Bacterial vaginosis is traditionally diagnosed with Amsel criteria, although Gram stain is the diagnostic standard 15.

What happens if I don’t get treated?

Bacterial vaginosis can cause some serious health risks, including 21:

- Increasing your chance of getting HIV if you have sex with someone who is infected with HIV;

- If you are HIV positive, increasing your chance of passing HIV to your sex partner;

- Making it more likely that you will deliver your baby too early if you have bacterial vaginosis while pregnant. Bacterial vaginosis can lead to premature birth or a low-birth-weight baby (smaller than 5 1/2 pounds at birth). All pregnant women with symptoms of bacterial vaginosis should be tested and treated if they have it;

- Increasing your chance of getting other STDs, such as chlamydia and gonorrhea. These bacteria can sometimes cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can make it difficult or impossible for you to have children.

Recurring bacterial vaginosis

It’s common for bacterial vaginosis to come back, usually within 3 months.

You’ll need to take treatment for longer (up to 6 months) if you keep getting bacterial vaginosis (you get it more than twice in 6 months). Your doctor or sexual health clinic will recommend how long you need to treat it.

They can also help identify if something is triggering your bacterial vaginosis, such as sex or your period.

Can bacterial vaginosis be cured?

Bacterial vaginosis will sometimes go away without treatment. But if you have symptoms of bacterial vaginosis you should be checked and treated. It is important that you take all of the medicine prescribed to you, even if your symptoms go away. Your doctor can treat bacterial vaginosis with antibiotics, but bacterial vaginosis may recur even after treatment. Treatment may also reduce the risk for some STDs (sexually transmitted diseases).

Male sex partners of women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis generally do not need to be treated. bacterial vaginosis may be transferred between female sex partners 35.

How can I lower my risk of bacterial vaginosis?

Researchers do not know exactly how bacterial vaginosis spreads. Steps that might lower your risk of bacterial vaginosis include:

- Keeping your vaginal bacteria balanced. Use warm water only to clean the outside of your vagina. You do not need to use soap. Even mild soap can cause irritate your vagina. Always wipe front to back from your vagina to your anus. Keep the area cool by wearing cotton or cotton-lined underpants.

- Not douching. Douching upsets the balance of good and harmful bacteria in your vagina. This may raise your risk of bacterial vaginosis. It may also make it easier to get bacterial vaginosis again after treatment. Doctors do not recommend douching.

- Not having sex. Researchers are still studying how women get bacterial vaginosis. You can get bacterial vaginosis without having sex, but bacterial vaginosis is more common in women who have sex.

- Limiting your number of sex partners. Researchers think that your risk of getting bacterial vaginosis goes up with the number of partners you have.

How can I protect myself if I am a female and my female partner has bacterial vaginosis?

If your partner has bacterial vaginosis, you might be able to lower your risk by using protection during sex.

- Use a dental dam every time you have sex. A dental dam is a thin piece of latex that is placed over the vagina before oral sex.

- Cover sex toys with condoms before use. Remove the condom and replace it with a new one before sharing the toy with your partner.

What is the difference between bacterial vaginosis and a vaginal yeast infection?

Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal yeast infections are both common causes of vaginal discharge. They have similar symptoms, so it can be hard to know if you have bacterial vaginosis or a yeast infection. Only your doctor or nurse can tell you for sure if you have bacterial vaginosis.

With bacterial vaginosis, your discharge may be white or gray but may also have a fishy smell. Discharge from a yeast infection may also be white or gray but may look like cottage cheese.

What should I do if I have bacterial vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginosis is easy to treat. If you think you have bacterial vaginosis:

- See a doctor. Antibiotics will treat bacterial vaginosis.

- Take all of your medicine. Even if symptoms go away, you need to finish all of the antibiotic.

- Tell your sex partner(s) if she is female so she can be treated.

- Avoid sexual contact until you finish your treatment.

- See your doctor again if you have symptoms that don’t go away within a few days after finishing the antibiotic.

Is it safe to treat pregnant women who have bacterial vaginosis?

Yes. The medicine used to treat bacterial vaginosis is safe for pregnant women. All pregnant women with symptoms of bacterial vaginosis should be tested and treated if they have it.

If you do have bacterial vaginosis, you can be treated safely at any stage of your pregnancy. You will get the same antibiotic given to women who are not pregnant.

Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

Pregnant women can get bacterial vaginosis. Pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis are more likely to have babies born premature (early) or with low birth weight than pregnant women without bacterial vaginosis. Low birth weight means having a baby that weighs less than 5.5 pounds at birth.

Treatment is especially important for pregnant women and is recommended for all symptomatic pregnant women. Studies have been undertaken to determine the efficacy of bacterial vaginosis treatment among pregnant women, including two trials demonstrating that metronidazole was efficacious during pregnancy using the 250-mg regimen 36, 37; however, metronidazole administered at 500 mg twice daily can be used. One trial involving a limited number of participants revealed treatment with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily to be equally effective as metronidazole gel, with cure rates of 70% using Amsel criteria to define cure 38. Another trial demonstrated a cure rate of 85% using Gram-stain criteria after treatment with oral clindamycin 39. Multiple studies and meta-analyses have failed to demonstrate an association between metronidazole use during pregnancy and teratogenic or mutagenic effects in newborns 40, 41. Although older studies indicated a possible link between use of vaginal clindamycin during pregnancy and adverse outcomes for the newborn, newer data demonstrate that this treatment approach is safe for pregnant women 42. Because oral therapy has not been shown to be superior to topical therapy for treating symptomatic bacterial vaginosis in effecting cure or preventing adverse outcomes of pregnancy, symptomatic pregnant women can be treated with either of the oral or vaginal regimens recommended for nonpregnant women. Although adverse pregnancy outcomes, including premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, preterm birth, intra-amniotic infection, and postpartum endometritis have been associated with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis in some observational studies, treatment of bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women can reduce the signs and symptoms of vaginal infection. A meta-analysis has concluded that no antibiotic regimen prevented preterm birth (early or late) in women with bacterial vaginosis (symptomatic or asymptomatic). However, in one study, oral bacterial vaginosis therapy reduced the risk for late miscarriage, and in two additional studies, such therapy decreased adverse outcomes in the neonate 43.

Treatment of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women who are at high risk for preterm delivery (i.e., those with a previous preterm birth) has been evaluated by several studies, which have yielded mixed results. Seven trials have evaluated treatment of pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis at high risk for preterm delivery: one showed harm 44, two showed no benefit 45, 46, and four demonstrated benefit 36, 37, 47, 48.

Similarly, data are inconsistent regarding whether treatment of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women who are at low risk for preterm delivery reduces adverse outcomes of pregnancy. One trial demonstrated a 40% reduction in spontaneous preterm birth among women using oral clindamycin during weeks 13–22 of gestation 48. Several additional trials have shown that intravaginal clindamycin given at an average gestation of >20 weeks did not reduce likelihood of preterm birth 46, 49. Therefore, evidence is insufficient to recommend routine screening for bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic pregnant women at high or low risk for preterm delivery for the prevention of preterm birth 50.

Although metronidazole crosses the placenta, no evidence of teratogenicity or mutagenic effects in infants has been found in multiple cross-sectional and cohort studies of pregnant women 51. Data suggest that metronidazole therapy poses low risk in pregnancy 52.

Metronidazole is secreted in breast milk. With maternal oral therapy, breastfed infants receive metronidazole in doses that are less than those used to treat infections in infants, although the active metabolite adds to the total infant exposure. Plasma levels of the drug and metabolite are measurable, but remain less than maternal plasma levels 53. Although several reported case series found no evidence of metronidazole-associated adverse effects in breastfed infants, some clinicians advise deferring breastfeeding for 12–24 hours following maternal treatment with a single 2-g dose of metronidazole 54. Lower doses produce a lower concentration in breast milk and are considered compatible with breastfeeding 55. Data from studies of human subjects are limited regarding the use of tinidazole in pregnancy; however, animal data suggest that such therapy poses moderate risk. Thus tinidazole should be avoided during pregnancy 52.

Bacterial vaginosis symptoms

Approximately 50 to 75% of women with bacterial vaginosis don’t have any signs or symptoms 56. At other times, bacterial vaginosis may cause 57, 58:

- A white (milky) or gray vaginal discharge that coats the walls of the vagina. It may also be foamy or watery.

- Vaginal discharge with an unpleasant or fish-like odor (“fishy smell”), especially after sex and around the time of menstruation.

- Vaginal pain or itching inside and outside the vagina

- Burning during urination

- Vaginal irritation

These symptoms may be similar to vaginal yeast infections and other health problems. Only your doctor or nurse can tell you for sure whether you have bacterial vaginosis. Doctors are unsure of the incubation period for bacterial vaginosis.

Symptoms may remit spontaneously. Bacterial vaginosis does not typically cause itch (pruritus), burning, dysuria (discomfort, pain or burning when urinating), painful intercourse (dyspareunia), vaginal inflammation, or vulvar swelling 58. Qualitative studies have shown that bacterial vaginosis can negatively impact self-esteem, sexual relationships, and quality of life 5.

Bacterial vaginosis complications

Bacterial vaginosis doesn’t generally cause complications. Sometimes, having bacterial vaginosis may lead to:

- Preterm birth. In pregnant women, bacterial vaginosis is linked to premature deliveries and low birth weight babies.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Having bacterial vaginosis makes women more susceptible to sexually transmitted infections, such as HIV, herpes simplex virus, chlamydia or gonorrhea. If you have HIV, bacterial vaginosis increases the odds that you’ll pass the virus on to your partner.

- Infection risk after gynecologic surgery. Having bacterial vaginosis may increase the risk of developing a post-surgical infection after procedures such as hysterectomy or dilation and curettage (D&C).

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Bacterial vaginosis can sometimes cause PID, an infection of the uterus and the fallopian tubes that can increase the risk of infertility.

Bacterial vaginosis causes

Bacterial vaginosis occurs when there’s a change in the natural balance of bacteria in your vagina. What causes this to happen isn’t fully known, but you’re more likely to get it if:

- you’re sexually active

- you’ve had a change of partner

- you have an IUD (contraception intrauterine device)

- you use perfumed products in or around your vagina

Bacterial vaginosis is not classed as an STI, even though it can be triggered by sex. A woman can pass it to another woman during sex.

But women who haven’t had sex can also get bacterial vaginosis.

Current understanding of the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis suggests loss of the normal hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) producing Lactobacillus species in the vagina by multiple facultative and strict anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Prevotella sp. and Mobiluncus sp.), Gardnerella Vaginalis, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, and numerous fastidious or uncultivated anaerobes, which leads to a subsequent vaginal dysbiosis and a proinflammatory state 1. To date, however, the exact cause of bacterial vaginosis has not been determined, despite extensive research 59. Some women experience transient vaginal microbial changes, whereas others experience them for longer intervals of time. Among women presenting for care, bacterial vaginosis is the most prevalent cause of vaginal discharge or malodor; however, in a nationally representative survey, most women with bacterial vaginosis were asymptomatic 60.

Bacterial vaginosis is associated with having multiple male or female partners, a new sex partner, douching, lack of condom use, and lack of vaginal lactobacilli; women who have never been sexually active are rarely affected 61. The cause of the microbial alteration that precipitates bacterial vaginosis is not fully understood, and whether bacterial vaginosis results from acquisition of a single sexually transmitted pathogen is not known. Nonetheless, women with bacterial vaginosis are at increased risk for the acquisition of some STDs (e.g., HIV, N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and HSV- 2), complications after gynecologic surgery, complications of pregnancy, and recurrence of bacterial vaginosis 62. Bacterial vaginosis also increases the risk for HIV transmission to male sex partners 13. Although bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria can be found in the male genitalia, treatment of male sex partners has not been beneficial in preventing the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis 14.

The following summarizes current step-by-step conceptual models for the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis 1, 2, 63:

- In the baseline state, in a healthy vaginal microbiome, Lactobacillus species are dominant, and they produce lactic acid from glycogen, a process that maintains a low vaginal pH; this acidic pH environment inhibits the growth of other bacterial species that are normally present in the vagina at very low levels.

- The process of vaginal dysbiosis usually begins with colonization of the vagina with a virulent strain of Gardnerella vaginalis, typically following a sexual exposure; the proliferation of this organism displaces vaginal lactobacilli and creates a biofilm scaffolding conducive to recruiting Prevotella bivia (and other bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria).

- Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella bivia engage in a synergistic relationship in which proteolysis by Gardnerella vaginalis produces amino acids that enhance the growth of Prevotella bivia. In turn, ammonia produced by Prevotella bivia enhances the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis.

- Sialidase produced by both Prevotella bivia and Gardnerella vaginalis promotes breakdown of the mucin layer of the vaginal epithelium and increase adherence of other strict anaerobes, including Atopobium vaginae, Megasphaera type I, and others which join the bacterial vaginosis biofilm on the upper layers.

- Atopobium vaginae stimulates a strong host immune response from vaginal epithelial cells, leading to localized cytokine and beta-defensin production

- Gradually the healthy normal dominant vaginal lactobacilli are replaced by Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria-2 (BVAB-2), and Megasphaera type I.

- In the final phase of this transition to bacterial vaginosis, mucus degradation occurs, the vaginal pH is elevated, multiple harmful compounds are produced (biogenic amines, toxic metabolites, and proinflammatory cytokines)—all resulting in a final state of vaginal dysbiosis and inflammation, which may progress to cause vaginal symptoms and adverse outcomes associated with this infection.

Risk factors for developing bacterial vaginosis

Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis include:

- Having multiple sex partners or a new sex partner. Doctors don’t fully understand the link between sexual activity and bacterial vaginosis, but the condition occurs more often in women who have multiple sex partners or a new sex partner. Bacterial vaginosis also occurs more frequently in women who have sex with women.

- Douching. The practice of rinsing out your vagina with water or a cleansing agent (douching) upsets the natural balance of your vagina. This can lead to an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria, and cause bacterial vaginosis. Since the vagina is self-cleaning, douching isn’t necessary.

- Natural lack of lactobacilli bacteria. If your natural vaginal environment doesn’t produce enough of the good lactobacilli bacteria, you’re more likely to develop bacterial vaginosis.

Bacterial vaginosis prevention

To help prevent bacterial vaginosis:

- Minimize vaginal irritation. Use mild, nondeodorant soaps and unscented tampons or pads.

- Don’t douche. Your vagina doesn’t require cleansing other than normal bathing. Frequent douching disrupts the vaginal balance and may increase your risk of vaginal infection. Douching won’t clear up a vaginal infection.

- Avoid a sexually transmitted infection. Use a male latex condom, limit your number of sex partners or abstain from intercourse to minimize your risk of a sexually transmitted infection.

Bacterial vaginosis diagnosis

Before you see a doctor or nurse for a test:

- Don’t douche or use vaginal deodorant sprays. They might cover odors that can help your doctor diagnose bacterial vaginosis. They can also irritate your vagina.

- Make an appointment for a day when you do not have your period.

There are tests to find out if you have bacterial vaginosis. Your doctor or nurse takes a sample of vaginal discharge. Your doctor or nurse may then look at the sample under a microscope, use an in-office test, or send it to a lab to check for harmful bacteria. Your doctor or nurse may also see signs of bacterial vaginosis during an exam.

Bacterial vaginosis can be diagnosed by the use of clinical criteria (i.e., Amsel’s Diagnostic Criteria) 64 or Gram stain. A Gram stain (considered the gold standard laboratory method for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis) is used to determine the relative concentration of lactobacilli (i.e., long Gram-positive rods), Gram-negative and Gram-variable rods and cocci (i.e., Gardnerella Vaginalis, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and peptostreptococci), and curved Gram-negative rods (i.e., Mobiluncus) characteristic of bacterial vaginosis. Clinical criteria require three of the following symptoms or signs:

- homogeneous, thin, white discharge that smoothly coats the vaginal walls;

- clue cells (e.g., vaginal epithelial cells studded with adherent coccobacilli) on microscopic examination (see Figure 3);

- pH of vaginal fluid >4.5 (a vaginal pH of 4.5 or higher is a sign of bacterial vaginosis); or

- a fishy odor of vaginal discharge before or after addition of 10% potassium hydroxide (i.e., the Whiff test).

Detection of three of these criteria has been correlated with results by Gram stain 65. Other tests, including Affirm VP III (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), a DNA hybridization probe test for high concentrations of Gardnerella Vaginalis, and the OSOM bacterial vaginosis Blue test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Framingham, MA), which detects vaginal fluid sialidase activity, have acceptable performance characteristics compared with Gram stain. Although a prolineaminopeptidase card test is available for the detection of elevated pH and trimethylamine, it has low sensitivity and specificity and therefore is not recommended. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been used in research settings for the detection of a variety of organisms associated with bacterial vaginosis, but evaluation of its clinical utility is still underway. Detection of specific organisms might be predictive of bacterial vaginosis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 66. Additional validation is needed before these tests can be recommended to diagnose bacterial vaginosis. Culture of Gardnerella Vaginalis is not recommended as a diagnostic tool because it is not specific. Cervical Pap tests have no clinical utility for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis because of their low sensitivity and specificity.

Although multiple nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are commercially available for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis in symptomatic women, only two of these are cleared by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA): BD MAX Vaginal Panel and Aptima BV 67, 68. These tests are currently intended only for use in women with vaginitis symptoms, and can be run using a self-obtained or clinician-collected vaginal swab specimens, with results available within 24 hours 69.

- BD MAX Vaginal Panel: The BD MAX Vaginal Panel is a multiplex, real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay used to evaluate women with vaginitis symptoms. This assay can detect major Lactobacillus species that are present in a healthy vaginal microbiota (L. crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and prominent bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria (G. vaginalis, A. vaginae, BVAB-2, and Megasphaera type 1) 67. In addition, the BD MAX Vaginal Panel can detect organisms responsible for causing trichomoniasis and vulvovaginal candidiasis 68. This assay bases the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis on the relative concentrations of the healthy Lactobacillus species and the bacterial vaginosis-causing organisms, with a final determination based on a proprietary algorithm 67. For the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis, this test has a reported sensitivity with clinician-collected specimens of 90.5% and specificity of 85.8%; similar results were seen with self-obtained specimens 68.

- Aptima BV Test: The Aptima BV test can be used in symptomatic women to detect certain Lactobacillus species (L. Crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii) and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria (G. vaginalis and A. vaginae). This test has a reported sensitivity with clinician-collected specimens of 95.0% and specificity of 89.6%; similar results were seen with self-obtained specimens 70.

Bacterial vaginosis treatment

Treatment is recommended for women with symptoms 67. The established benefits of therapy in nonpregnant women are to relieve vaginal symptoms and signs of infection. Other potential benefits to treatment include reduction in the risk for acquiring Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis, HIV, and herpes simplex type 2 71. The use of probiotics that target vaginal repletion of Lactobacillus species is an attractive concept for treatment and for prevention of recurrences, but this strategy is not recommended as a primary or adjunctive therapy for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis at this time 72, 67.

Bacterial vaginosis medication

Recommended antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis 67:

- Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days;

- OR

- Metronidazole gel 0.75%, one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally, once a day for 5 days;

- OR

- Clindamycin cream 2%, one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Accumulating reports have refuted prior warnings that metronidazole (or tinidazole) causes a disulfiram reaction in persons who ingest alcohol while taking these antibiotics 73. Accordingly, experts now consider it unnecessary for persons to refrain from ingesting alcohol when they are taking metronidazole or tinidazole 73, 67.

Clindamycin cream is oil-based and might weaken latex condoms and diaphragms for 5 days after use (refer to clindamycin product information for additional information).

Women should be advised to refrain from sexual activity or use condoms consistently and correctly during the bacterial vaginosis treatment regimen. Douching might increase the risk for relapse, and no data support the use of douching for treatment or relief of symptoms.

Intravaginal clindamycin cream is preferred in case of allergy or intolerance to metronidazole or tinidazole. Intravaginal metronidazole gel can be considered for women who are not allergic to metronidazole but do not tolerate oral metronidazole.

Alternative bacterial vaginosis medicine 67:

- Tinidazole 2 g orally once daily for 2 days;

- OR

- Tinidazole 1 g orally once daily for 5 days;

- OR

- Clindamycin 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days;

- OR

- Clindamycin ovules 100 mg intravaginally once at bedtime for 3 days

- Note: Clindamycin ovules use an oleaginous base that might weaken latex or rubber products (e.g., condoms and vaginal contraceptive diaphragms). Use of such products within 72 hours following treatment with clindamycin ovules is not recommended.

- OR

- Secnidazole 2 g oral granules in a single dose

- Note: Oral granules should be sprinkled onto unsweetened applesauce, yogurt, or pudding before ingestion. A glass of water can be taken after administration to aid in swallowing.

Alcohol consumption should be avoided during treatment with nitroimidazoles. To reduce the possibility of a disulfiram-like reaction, abstinence from alcohol use should continue for 72 hours after completion of tinidazole.

Alternative regimens include several tinidazole regimens 74 or clindamycin (oral or intravaginal) 75. An additional regimen includes metronidazole (750-mg extended release tablets orally once daily for 7 days); however, data on the performance of this alternative regimen are limited.

Certain studies have evaluated the clinical and microbiologic efficacy of using intravaginal lactobacillus formulations to treat bacterial vaginosis and restore normal flora 76. Overall, no studies support the addition of any available lactobacillus formulations or probiotic as an adjunctive or replacement therapy in women with bacterial vaginosis. Further research efforts to determine the role of these regimens in bacterial vaginosis treatment and prevention are ongoing.

Management of Sex Partners

Data from clinical trials indicate that a woman’s response to therapy and the likelihood of relapse or recurrence are not affected by treatment of her sex partner(s) 14. Therefore, routine treatment of sex partners is not recommended. However, a pilot study reported that male partner treatment (i.e., metronidazole 400 mg orally 2 times/day in conjunction with 2% clindamycin cream applied topically to the penile skin 2 times/day for 7 days) of women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis had an immediate and sustained effect on the composition of the vaginal microbiota, with an overall decrease in bacterial diversity at day 28 77. Male partner treatment also had an immediate effect on the composition of the penile microbiota; however, this was not as pronounced at day 28, compared with that among women. A phase 3 multicenter randomized double-blinded trial evaluating the efficacy of a 7-day oral metronidazole regimen versus placebo for treatment of male sex partners of women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis did not find that male partner treatment reduced bacterial vaginosis recurrence in female partners, although women whose male partners adhered to multidose metronidazole were less likely to experience treatment failure 78. Furthermore, because female sex partners are often concurrent for bacterial vaginosis status, the option of screening and treatment of female sex partners could be considered, but this approach has not been studied rigorously in clinical trials 79.

Post-Treatment Follow-Up

Follow-up visits are unnecessary if symptoms resolve 67. Because persistent or recurrent bacterial vaginosis is common, women should be advised to return for evaluation if symptoms recur 67. Detection of certain bacterial vaginosis-associated organisms has been associated with antimicrobial resistance and might be predictive of risk for subsequent treatment failure 80. Limited data are available regarding optimal management strategies for women with persistent or recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Using a different recommended treatment regimen can be considered in women who have a recurrence; however, retreatment with the same recommended regimen is an acceptable approach for treating persistent or recurrent bacterial vaginosis after the first occurrence 81. For women with multiple recurrences after completion of a recommended regimen, 0.75% metronidazole gel twice weekly for 4–6 months has been shown to reduce recurrences, although this benefit might not persist when suppressive therapy is discontinued 82. Limited data suggest that an oral nitroimidazole (metronidazole or tinidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days) followed by intravaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 21 days and then suppressive 0.75% metronidazole gel twice weekly for 4–6 months for those women in remission might be an option for women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis 83. Monthly oral metronidazole 2g administered with fluconazole 150 mg has also been evaluated as suppressive therapy; this regimen reduced the incidence of bacterial vaginosis and promoted colonization with normal vaginal flora 84.

HIV Infection

Bacterial vaginosis appears to recur with higher frequency in women who have HIV infection 85. Women with HIV who have bacterial vaginosis should receive the same treatment regimen as those who do not have HIV infection.

Metronidazole (or Tinidazole) Allergy or Intolerance

For women who are allergic or intolerant to metronidazole (or tinidazole), the preferred option is to treat with clindamycin cream—one full applicator (5 grams) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days 67. Intravaginal metronidazole gel can be considered for women who are not allergic to metronidazole but do not tolerate oral metronidazole.

Treatment of pregnant women with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis

All pregnant women who have symptomatic bacterial vaginosis should receive treatment since symptomatic bacterial vaginosis is clearly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including premature rupture of membranes, preterm birth, intra-amniotic infection, and postpartum endometritis 27, 28. Furthermore, treating symptomatic bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy reduces symptoms and may reduce certain adverse obstetrical outcomes, such as late miscarriage. Any of the recommended bacterial vaginosis treatments for nonpregnant women (oral metronidazole, metronidazole gel, and clindamycin cream) as well as certain alternative regimens (oral clindamycin and clindamycin ovules) can be used to treat women with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy 67. Metronidazole crosses the placenta and is excreted in breast milk, but it has not been linked to teratogenic effects 86. Tinidazole is not recommended during pregnancy due to evidence of fetal harm in animal studies. There are insufficient data in pregnancy to recommend using secnidazole in pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis. Several specific preparations should not be used during pregnancy, including metronidazole 1.3% vaginal gel, the 750-mg vaginal metronidazole tablets, and the Clindesse brand of 2% clindamycin vaginal cream, which is a high-dose single application treatment for bacterial vaginosis. For breastfeeding mothers with symptomatic bacterial vaginosis, metronidazole can be used 67.

Management of pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

Since routine screening for bacterial vaginosis is not recommended for pregnant women who do not have vaginal symptoms, the need to address the treatment of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy should not routinely arise. Available data suggest no benefit for the treatment of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women who are considered at low risk for preterm delivery 87. For pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (i.e., those with a previous preterm birth or late miscarriage), the impact of treating asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis is not clear and available data are conflicting—four studies showed benefit with treatment 88, 89, 90, 91, two showed no benefit 92, 93 and one showed harm 94.

Treatment of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women at low risk for preterm delivery has not been reported to reduce adverse outcomes of pregnancy in a large multicenter randomized controlled trial 87. Therefore, routine screening for bacterial vaginosis among asymptomatic pregnant women at high or low risk for preterm delivery for preventing preterm birth is not recommended.

Treatment in women with HIV

Women with HIV experience higher prevalence and longer persistence of bacterial vaginosis compared to women without HIV 95. The treatment of bacterial vaginosis in women with HIV should be the same as for women without HIV 67.

Treatment of Recurrent Bacterial Vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis recurs in approximately 30% of women within the first 3 months following treatment, and in up to 50% of women after 6 to 12 months 96. Very little is known about antimicrobial resistance with pathogens that cause bacterial vaginosis, although clinical experience suggests that treatment failure from true antimicrobial resistance is uncommon 10.

- Single Recurrence: Women with a single recurrence can be treated with either the same recommended regimen or a different recommended regimen 67.

- Multiple Recurrences: For women who experience multiple recurrences of bacterial vaginosis after completing treatment with a recommended regimen, a different approach from the initial treatment is recommended. Based on available data, the following regimens are suggested as options for these women 67:

- Metronidazole gel (0.75%) vaginal suppository twice weekly for at least 3 months 97.

- Metronidazole 750 mg vaginal suppository twice weekly for at least 3 months 98.

- Metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily (or tinidazole 500 mg orally twice daily) for 7 days, followed by intravaginal boric acid 600 mg daily for 21 days, followed by suppressive therapy with intravaginal metronidazole gel (0.75%) twice weekly for 4 to 6 months 99.

- Metronidazole 2 grams orally once per month plus fluconazole 150 mg orally once per month given over a 12-month timeframe has also been evaluated as periodic presumptive therapy; this approach resulted in fewer episodes of bacterial vaginosis in one study when compared to placebo 100.

- Astodrimer 1% gel (a dendrimer-based microbicide) at a dose of 5 grams vaginally every other day for 16 weeks 101.

- Muzny, C. A., Łaniewski, P., Schwebke, J. R., & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. (2020). Host-vaginal microbiota interactions in the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis. Current opinion in infectious diseases, 33(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000620

- Muzny, C. A., Taylor, C. M., Swords, W. E., Tamhane, A., Chattopadhyay, D., Cerca, N., & Schwebke, J. R. (2019). An Updated Conceptual Model on the Pathogenesis of Bacterial Vaginosis. The Journal of infectious diseases, 220(9), 1399–1405. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz342

- Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, Krohn MA, Gibbs RS, Martin DH, Cotch MF, Edelman R, Pastorek JG 2nd, Rao AV, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec 28;333(26):1737-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604

- Peebles K, Velloza J, Balkus JE, McClelland RS, Barnabas RV. High Global Burden and Costs of Bacterial Vaginosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2019 May;46(5):304-311. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000972

- Bautista, C. T., Wurapa, E., Sateren, W. B., Morris, S., Hollingsworth, B., & Sanchez, J. L. (2016). Bacterial vaginosis: a synthesis of the literature on etiology, prevalence, risk factors, and relationship with chlamydia and gonorrhea infections. Military Medical Research, 3, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-016-0074-5

- Klebanoff, M. A., Nansel, T. R., Brotman, R. M., Zhang, J., Yu, K. F., Schwebke, J. R., & Andrews, W. W. (2010). Personal hygienic behaviors and bacterial vaginosis. Sexually transmitted diseases, 37(2), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bc063c

- Klebanoff, M. A., Andrews, W. W., Zhang, J., Brotman, R. M., Nansel, T. R., Yu, K. F., & Schwebke, J. R. (2010). Race of male sex partners and occurrence of bacterial vaginosis. Sexually transmitted diseases, 37(3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c04865

- Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, Law M, Pirotta M, Garland SM, De Guingand D, Morton AN, Fairley CK. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Mar;56(6):777-86. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1030

- Schwebke JR, Desmond R. Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis in women at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Nov;32(11):654-8. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175396.10304.62

- Bradshaw, C. S., & Sobel, J. D. (2016). Current Treatment of Bacterial Vaginosis-Limitations and Need for Innovation. The Journal of infectious diseases, 214 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S14–S20. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw159

- Vodstrcil LA, Walker SM, Hocking JS, Law M, Forcey DS, Fehler G, Bilardi JE, Chen MY, Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS. Incident bacterial vaginosis (BV) in women who have sex with women is associated with behaviors that suggest sexual transmission of BV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Apr 1;60(7):1042-53. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1130

- Liu, C. M., Hungate, B. A., Tobian, A. A., Ravel, J., Prodger, J. L., Serwadda, D., Kigozi, G., Galiwango, R. M., Nalugoda, F., Keim, P., Wawer, M. J., Price, L. B., & Gray, R. H. (2015). Penile Microbiota and Female Partner Bacterial Vaginosis in Rakai, Uganda. mBio, 6(3), e00589. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00589-15

- Cohen CR, Lingappa JR, Baeten JM, et al. Bacterial vaginosis associated with increased risk of female-to-male HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis among African couples. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001251.

- Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacteria vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:822–30.

- Vaginitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018 Mar 1;97(5):321-329. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0301/p321.html

- Africa, C. W., Nel, J., & Stemmet, M. (2014). Anaerobes and bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy: virulence factors contributing to vaginal colonisation. International journal of environmental research and public health, 11(7), 6979–7000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110706979

- Huang, B., Fettweis, J. M., Brooks, J. P., Jefferson, K. K., & Buck, G. A. (2014). The changing landscape of the vaginal microbiome. Clinics in laboratory medicine, 34(4), 747–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cll.2014.08.006

- Ravel, J., Gajer, P., Abdo, Z., Schneider, G. M., Koenig, S. S., McCulle, S. L., Karlebach, S., Gorle, R., Russell, J., Tacket, C. O., Brotman, R. M., Davis, C. C., Ault, K., Peralta, L., & Forney, L. J. (2011). Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 4680–4687. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1002611107

- Gajer, P., Brotman, R. M., Bai, G., Sakamoto, J., Schütte, U. M., Zhong, X., Koenig, S. S., Fu, L., Ma, Z. S., Zhou, X., Abdo, Z., Forney, L. J., & Ravel, J. (2012). Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Science translational medicine, 4(132), 132ra52. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605

- Bacterial Vaginosis – CDC Fact Sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/std/bv/stdfact-bacterial-vaginosis.htm

- Bacterial Vaginosis. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm

- Klebanoff, M.A., et al. (2010). Personal Hygienic Behaviors and Bacterial Vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis; 37(2):94-9.

- Koumans, E.H., Sternberg, M., Bruce, C., McQuillan, G., Kendrick, J., Sutton, M., Markowitz, L. (2007). The Prevalence of Bacterial Vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004; Associations with Symptoms, Sexual Behaviors, and Reproductive Health (link is external). Sexually Transmitted Diseases; 34(11): 864-869.

- Ness, R.B., et al. (2003). Can known risk factors explain racial differences in the occurrence of bacterial vaginosis? (link is external) J Natl Med Assoc; 95:201–212.

- Madden, T. et al. (2012). Risk of bacterial vaginosis in users of the intrauterine device: a longitudinal study. Sex Transm Dis; 39(3): 217-222.

- Berger A, Kane KY. Clindamycin for vaginosis reduces prematurity and late miscarriage. J Fam Pract. 2003 Aug;52(8):603-4.

- Laxmi U, Agrawal S, Raghunandan C, Randhawa VS, Saili A. Association of bacterial vaginosis with adverse fetomaternal outcome in women with spontaneous preterm labor: a prospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jan;25(1):64-7. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.565390

- Nelson, D. B., Hanlon, A., Hassan, S., Britto, J., Geifman-Holtzman, O., Haggerty, C., & Fredricks, D. N. (2009). Preterm labor and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria among urban women. Journal of perinatal medicine, 37(2), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2009.026

- Oakeshott, P., Kerry, S., Hay, S., & Hay, P. (2004). Bacterial vaginosis and preterm birth: a prospective community-based cohort study. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 54(499), 119–122.

- Ravel J, Moreno I, Simón C. Bacterial vaginosis and its association with infertility, endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Mar;224(3):251-257. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.019

- Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, McQuillan G, Kendrick J, Sutton M, Markowitz LE. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Nov;34(11):864-9. https://journals.lww.com/stdjournal/Fulltext/2007/11000/The_Prevalence_of_Bacterial_Vaginosis_in_the.6.aspx

- Abou Chacra, L., Fenollar, F., & Diop, K. (2022). Bacterial Vaginosis: What Do We Currently Know?. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 11, 672429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.672429

- Bisht, Mithila & Agarwal, Shweta & Upadhyay, Deepak. (2015). Utility of Papanicolaou test in diagnosis of cervical lesions: a study in a tertiary care centre of western Uttar Pradesh. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 3. 1070. 10.5455/2320-6012.ijrms20150508

- Money, D. (2005). The laboratory diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 16, 77–79.

- Bacterial Vaginosis – CDC Fact Sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/std/BV/STDFact-Bacterial-Vaginosis.htm

- Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, et al. Reduced incidence of preterm delivery with metronidazole and erythromycin in women with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1732–6.

- Morales WJ, Schorr S, Albritton J. Effect of metronidazole in patients with preterm birth in preceding pregnancy and bacterial vaginosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;171:345–9.

- Yudin MH, Landers DV, Meyn L, et al. Clinical and cervical cytokine response to treatment with oral or vaginal metronidazole for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:527–34.

- Ugwumadu A, Reid F, Hay P, et al. Natural history of bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora in pregnancy and effect of oral clindamycin. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:114–9.

- Burtin P, Taddio A, Ariburnu O, et al. Safety of metronidazole in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172(2 Pt 1):525–9.

- Piper JM, Mitchel EF, Ray WA. Prenatal use of metronidazole and birth-defects – no association. Obstet Gynecol 1993;82:348–52.

- Lamont RF, Nhan-Chang CL, Sobel JD, et al. Treatment of abnormal vaginal flora in early pregnancy with clindamycin for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:177–90.

- Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, et al. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;1:CD000262.

- Odendaal HJ, Popov I, Schoeman J, et al. Preterm labour—is bacterial vaginosis involved? South African Medical Journal 2002;92:231–4.

- Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, et al. Metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med 2000;342:534–40.

- Vermeulen GM, Bruinse HW. Prophylactic administration of clindamycin 2% vaginal cream to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women with an increased recurrence risk: a randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1999;106:652–7.

- McDonald HM, O’Loughlin JA, Vigneswaran R, et al. Impact of metronidazole therapy on preterm birth in women with bacterial vaginosis flora (Gardnerella vaginalis): a randomised, placebo controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:1391–7.

- Ugwumadu A, Manyonda I, Reid F, et al. Effect of early oral clindamycin on late miscarriage and preterm delivery in asymptomatic women with abnormal vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361:983–8.

- Lamont RF, Duncan SL, Mandal D, et al. Intravaginal clindamycin to reduce preterm birth in women with abnormal genital tract flora. Obstet Gynecol 2003;101:516–22.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy to prevent preterm delivery: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:214–9.

- Koss CA, Baras DC, Lane SD, et al. Investigation of metronidazole use during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:4800–5.

- Briggs GC, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation, 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

- https://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/lactmed.htm

- Erickson SH, Oppenheim GL, Smith GH. Metronidazole in breast milk. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57:48–50.

- Golightly P, Kearney L. Metronidazole— is it safe to use with breastfeeding? United Kingdom National Health Service, UKMI;2012.

- Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, McQuillan G, Kendrick J, Sutton M, Markowitz LE. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Nov;34(11):864-9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074e565

- Eschenbach DA, Hillier S, Critchlow C, Stevens C, DeRouen T, Holmes KK. Diagnosis and clinical manifestations of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Apr;158(4):819-28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90078-6

- Reiter S, Kellogg Spadt S. Bacterial vaginosis: a primer for clinicians. Postgrad Med. 2019 Jan;131(1):8-18. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1546534

- Bacterial Vaginosis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm

- Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001-2004: associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:864–9.

- Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Morton A, et al. Early sexual experiences and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 2009;200:1662–70.

- Laxmi U, Agrawal S, Raghunandan C, et al. Association of bacterial vaginosis with adverse fetomaternal outcome in women with spontaneous preterm labor: a prospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:64–7.

- Muzny, C. A., Blanchard, E., Taylor, C. M., Aaron, K. J., Talluri, R., Griswold, M. E., Redden, D. T., Luo, M., Welsh, D. A., Van Der Pol, W. J., Lefkowitz, E. J., Martin, D. H., & Schwebke, J. R. (2018). Identification of Key Bacteria Involved in the Induction of Incident Bacterial Vaginosis: A Prospective Study. The Journal of infectious diseases, 218(6), 966–978. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy243

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med 1983;74:14–22.

- Schwebke JR, Hillier SL, Sobel JD, et al. Validity of the vaginal gram stain for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88(4 Pt 1):573–6.

- Cartwright CP, Lembke BD, Ramachandran K, et al. Development and validation of a semiquantitative, multitarget PCR assay for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50:2321–9.

- Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines – Bacterial Vaginosis 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/bv.htm

- Gaydos, C. A., Beqaj, S., Schwebke, J. R., Lebed, J., Smith, B., Davis, T. E., Fife, K. H., Nyirjesy, P., Spurrell, T., Furgerson, D., Coleman, J., Paradis, S., & Cooper, C. K. (2017). Clinical Validation of a Test for the Diagnosis of Vaginitis. Obstetrics and gynecology, 130(1), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002090

- Coleman, J. S., & Gaydos, C. A. (2018). Molecular Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis: an Update. Journal of clinical microbiology, 56(9), e00342-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00342-18

- Schwebke, J. R., Taylor, S. N., Ackerman, R., Schlaberg, R., Quigley, N. B., Gaydos, C. A., Chavoustie, S. E., Nyirjesy, P., Remillard, C. V., Estes, P., McKinney, B., Getman, D. K., & Clark, C. (2020). Clinical Validation of the Aptima Bacterial Vaginosis and Aptima Candida/Trichomonas Vaginitis Assays: Results from a Prospective Multicenter Clinical Study. Journal of clinical microbiology, 58(2), e01643-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01643-19

- Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, et al. Bacterial vaginosis assessed by gram stain and diminished colonization resistance to incident gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal genital infection. J Infect Dis 2010;202:1907–15.

- Cohen, C. R., Wierzbicki, M. R., French, A. L., Morris, S., Newmann, S., Reno, H., Green, L., Miller, S., Powell, J., Parks, T., & Hemmerling, A. (2020). Randomized Trial of Lactin-V to Prevent Recurrence of Bacterial Vaginosis. The New England journal of medicine, 382(20), 1906–1915. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1915254

- Mergenhagen, K. A., Wattengel, B. A., Skelly, M. K., Clark, C. M., & Russo, T. A. (2020). Fact versus Fiction: a Review of the Evidence behind Alcohol and Antibiotic Interactions. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 64(3), e02167-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02167-19

- Livengood CH, 3rd, Ferris DG, Wiesenfeld HC, et al. Effectiveness of two tinidazole regimens in treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110(2 Pt 1):302–9.

- Sobel J, Peipert JF, McGregor JA, et al. Efficacy of clindamycin vaginal ovule (3-day treatment) vs. clindamycin vaginal cream (7-day treatment) in bacterial vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2001;9:9–15.

- Hemmerling A, Harrison W, Schroeder A, et al. Phase 2a study assessing colonization efficiency, safety, and acceptability of Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 in women with bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:745–50.

- Plummer, E. L., Vodstrcil, L. A., Danielewski, J. A., Murray, G. L., Fairley, C. K., Garland, S. M., Hocking, J. S., Tabrizi, S. N., & Bradshaw, C. S. (2018). Combined oral and topical antimicrobial therapy for male partners of women with bacterial vaginosis: Acceptability, tolerability and impact on the genital microbiota of couples – A pilot study. PloS one, 13(1), e0190199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190199

- Schwebke, J. R., Lensing, S. Y., Lee, J., Muzny, C. A., Pontius, A., Woznicki, N., Aguin, T., & Sobel, J. D. (2021). Treatment of Male Sexual Partners of Women With Bacterial Vaginosis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 73(3), e672–e679. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1903

- Marrazzo, J. M., Antonio, M., Agnew, K., & Hillier, S. L. (2009). Distribution of genital Lactobacillus strains shared by female sex partners. The Journal of infectious diseases, 199(5), 680–683. https://doi.org/10.1086/596632

- Nyirjesy P, McIntosh MJ, Steinmetz JI, et al. The effects of intravaginal clindamycin and metronidazole therapy on vaginal mobiluncus morphotypes in patients with bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:197–202.

- Bunge KE, Beigi RH, Meyn LA, et al. The efficacy of retreatment with the same medication for early treatment failure of bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:711–3.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:1283–9.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:732–4.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect Dis 2008;197:1361–8.

- Jamieson DJ, Duerr A, Klein RS, et al. Longitudinal analysis of bacterial vaginosis: findings from the HIV epidemiology research study. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:656–63.

- Koss, C. A., Baras, D. C., Lane, S. D., Aubry, R., Marcus, M., Markowitz, L. E., & Koumans, E. H. (2012). Investigation of metronidazole use during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 56(9), 4800–4805. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.06477-11

- Subtil D, Brabant G, Tilloy E, Devos P, Canis F, Fruchart A, Bissinger MC, Dugimont JC, Nolf C, Hacot C, Gautier S, Chantrel J, Jousse M, Desseauve D, Plennevaux JL, Delaeter C, Deghilage S, Personne A, Joyez E, Guinard E, Kipnis E, Faure K, Grandbastien B, Ancel PY, Goffinet F, Dessein R. Early clindamycin for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy (PREMEVA): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Nov 17;392(10160):2171-2179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31617-9

- McDonald HM, O’Loughlin JA, Vigneswaran R, Jolley PT, Harvey JA, Bof A, McDonald PJ. Impact of metronidazole therapy on preterm birth in women with bacterial vaginosis flora (Gardnerella vaginalis): a randomised, placebo controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 Dec;104(12):1391-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11009.x

- Ugwumadu A, Manyonda I, Reid F, Hay P. Effect of early oral clindamycin on late miscarriage and preterm delivery in asymptomatic women with abnormal vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003 Mar 22;361(9362):983-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12823-1

- Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, DuBard MB, Copper RL. Reduced incidence of preterm delivery with metronidazole and erythromycin in women with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec 28;333(26):1732-6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332603

- Morales WJ, Schorr S, Albritton J. Effect of metronidazole in patients with preterm birth in preceding pregnancy and bacterial vaginosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Aug;171(2):345-7; discussion 348-9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70033-8

- Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, Hillier SL, Thom EA, Ernest JM, Heine RP, Nugent RP, Fischer ML, Leveno KJ, Wapner R, Varner M. Metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 24;342(8):534-40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420802

- Vermeulen GM, Bruinse HW. Prophylactic administration of clindamycin 2% vaginal cream to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women with an increased recurrence risk: a randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999 Jul;106(7):652-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08363.x

- Odendaal HJ, Popov I, Schoeman J, Smith M, Grové D. Preterm labour–is bacterial vaginosis involved? S Afr Med J. 2002 Mar;92(3):231-4.

- Jamieson DJ, Duerr A, Klein RS, Paramsothy P, Brown W, Cu-Uvin S, Rompalo A, Sobel J. Longitudinal analysis of bacterial vaginosis: findings from the HIV epidemiology research study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Oct;98(4):656-63. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01525-3

- Bradshaw, C. S., & Brotman, R. M. (2015). Making inroads into improving treatment of bacterial vaginosis – striving for long-term cure. BMC infectious diseases, 15, 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1027-4

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, Nyirjesy P, Wiesenfeld HC, Peipert J, Soper D, Ohmit SE, Hillier SL. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 May;194(5):1283-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.041

- Aguin T, Akins RA, Sobel JD. High-dose vaginal maintenance metronidazole for recurrent bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. Sex Transm Dis. 2014 May;41(5):290-1. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000123

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Nov;36(11):732-4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b08456

- McClelland, R. S., Richardson, B. A., Hassan, W. M., Chohan, V., Lavreys, L., Mandaliya, K., Kiarie, J., Jaoko, W., Ndinya-Achola, J. O., Baeten, J. M., Kurth, A. E., & Holmes, K. K. (2008). Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. The Journal of infectious diseases, 197(10), 1361–1368. https://doi.org/10.1086/587490

- Schwebke, J. R., Carter, B. A., Waldbaum, A. S., Agnew, K. J., Paull, J., Price, C. F., Castellarnau, A., McCloud, P., & Kinghorn, G. R. (2021). A phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of Astodrimer 1% Gel for preventing recurrent bacterial vaginosis. European journal of obstetrics & gynecology and reproductive biology: X, 10, 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurox.2021.100121