Common benign skin lesions

Benign skin lesions are harmless skin lesions because they don’t turn into skin cancer (malignant skin lesions), but some benign skin lesions can be quite unsightly. Diagnosis usually is based on the appearance of the skin lesion and the patient’s clinical history, although biopsy is sometimes required. Treatment includes excision, cryotherapy (freezing), curettage with or without electrodesiccation, and pharmacotherapy, and is based on the type of tumor and its location.

Types of benign skin lesions

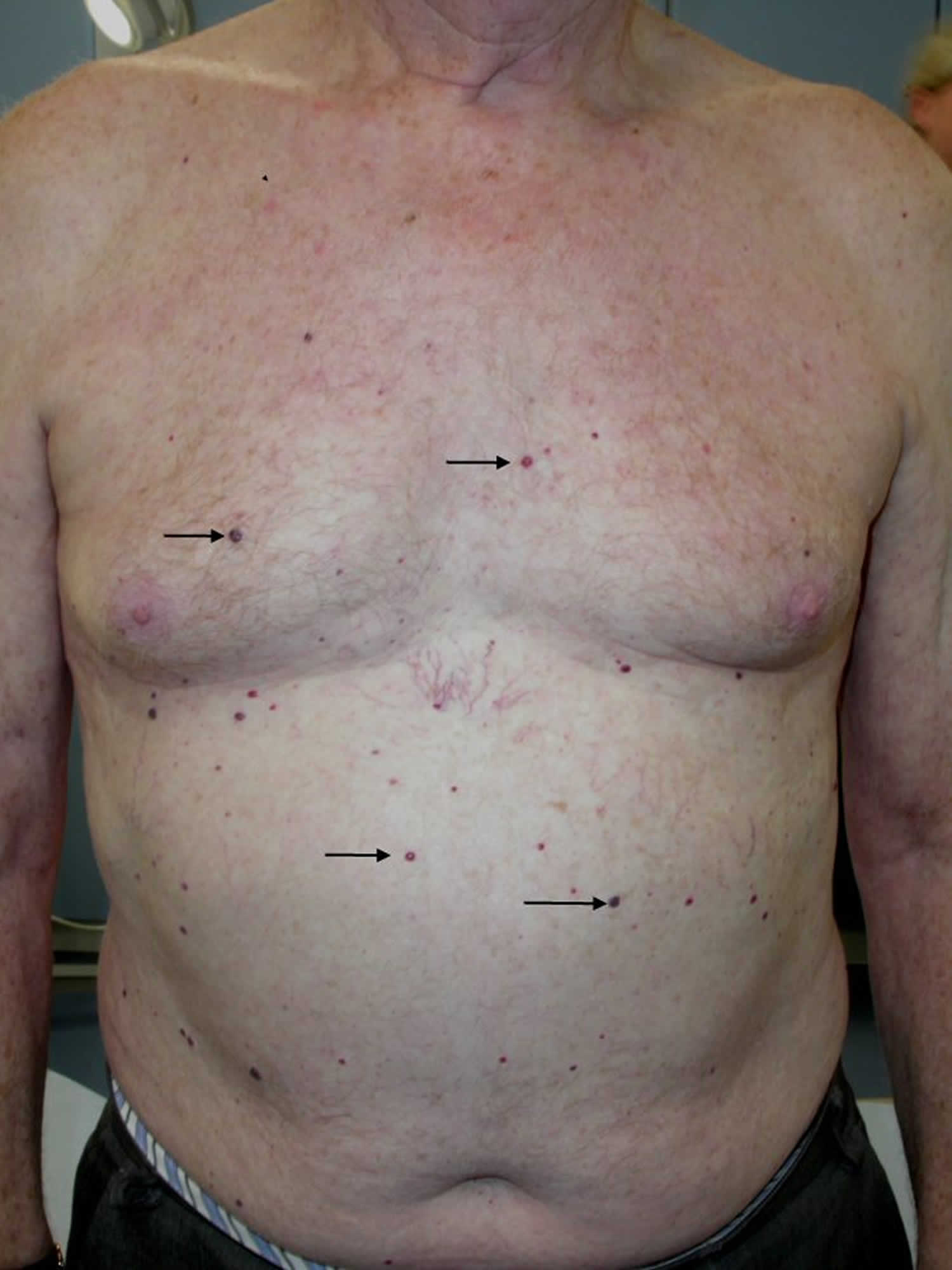

A skin tag also called acrochordon, is an extremely common soft benign (harmless) lesion that appears to hang off the skin. Skin tags develop in both men and women as they grow older. Skin tags (acrochordons) are made up of loosely arranged collagen fibers and blood vessels surrounded by a thickened or thinned-out epidermis. Skin tags (acrochordons) consist of hyperplastic soft dermis and epidermis, and are usually skin colored or brownish (Figure 1). They are generally 1 to 5 mm in size, although they may become larger. The most common locations are in skin folds (e.g., neck, armpits, groin), where skin irritation can be a causative factor. They tend to be more numerous in obese persons and in those with type 2 diabetes mellitus. They occur in 25% to 46% of adults and increase with age and during pregnancy 1. Studies have found that acrochordons are associated with the metabolic syndrome (obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, and elevated C-reactive protein levels) 2. This suggests they may be viewed as cutaneous clues for cardiovascular disease.

Skin tag is also called:

- Acrochordon

- Papilloma

- Fibroepithelial polyp

- Soft fibroma

- Pedunculated (this means it is on a stalk)

- Filiform (this means it is thread-like)

Note: Seborrhoeic keratosis, viral warts or molluscum contagiosum may resemble skin tags.

It is not known what causes skin tags. However, the following factors may play a role:

- Chaffing and irritation from skin rubbing together

- High levels of growth factors, particularly during pregnancy or in acromegaly (gigantism)

- Insulin resistance (syndrome X)

- Human papillomavirus (wart virus)

Diagnosis is based on the appearance and location of lesions. They must be differentiated from neurofibromas, seborrheic keratoses, and pedunculated nevi. There have been rare case reports of skin tags that were found to be basal or squamous cell carcinomas.

Skin tags can be removed for cosmetic reasons by the following methods:

- Cryotherapy (freezing)

- Surgical excision (simple scissor or shave excision)

- Electrosurgery or electrodesiccation (diathermy). Electrodesiccation causes less hypopigmentation than cryotherapy and is the preferred treatment in nonwhite patients.

- Ligation (a suture is tied around the neck of the skin tag)

Small ones can be frozen. An ear speculum placed over a small lesion may be helpful in directing the freeze pattern during cryosurgery. Larger ones can be shaved off and diathermied under local anaesthetic.

Figure 1. Skin tags

Seborrheic keratosis (age spots)

Seborrheic keratoses may start quite early in life, and it is not uncommon to find them on teenagers. Seborrheic keratoses are hyperkeratotic lesions of the epidermis, which often appear to be “stuck on” the surface of the skin. They tend to become larger and more numerous with age. Seborrheic keratoses vary in color, from skin-colored to pink, tan to brown to black, and usually have a well-circumscribed border. Most lesions have a rough surface and usually range in size from 2 mm to 3 cm in diameter, but can be larger. Seborrheic keratoses eventually progress from an initial hyperpigmented macule to the characteristic plaque (Figure 3) 3. The trunk is the most common site, but the lesions also can be found on the extremities, face, and scalp 4. Even though seborrheic keratoses are quite benign, malignancies do occasionally arise within a lesion. Individual lesions may also become uncomfortable or unsightly, and treatment of such lesions is often appropriate. Small ones can be frozen. Larger ones can be scraped off and diathermied under local anesthetic.

Men and women are affected equally by seborrheic keratoses, and the incidence increases with age. Stucco keratoses, a variant of seborrheic keratosis, are multiple skin-colored or white, dry, scaly lesions often seen on the extremities. Dermatosis papulosa nigra is another type of seborrheic keratosis consisting of multiple small, brown or black papules commonly found on the face of dark-skinned persons.

Differentiating between seborrheic keratoses and melanomas is a challenge. Both have variable dark colors, the potential for large size, and irregularity. A key differentiating feature is that a melanoma tends to vary more in color, such as browns, blues, black, grays, and reds, whereas a seborrheic keratosis usually is limited to shades of brown and black 3. Additionally, the surface of seborrheic keratoses tends to be rougher than that of melanomas, which is smooth, yet often friable. Therefore, care should be taken with any seborrhoeic keratosis that is unusual. Even very experienced clinicians are occasionally misled by such lesions, which may turn out to be a pigmented patch of Bowen’s disease or a melanoma. If there is significant doubt about a seborrheic keratosis, the lesion should be biopsied or carefully reassessed in eight weeks or the patient sent for a second opinion.

Seborrheic keratoses are often asymptomatic but can become irritated and inflamed spontaneously or because of chafing from clothing. Treatment of seborrheic keratoses is indicated for cosmetic reasons, to decrease irritation, or to rule out malignancy. Numerous methods of treatment are effective, but the most commonly used are cryosurgery, curettage, and excision. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen is effective for most seborrheic keratoses, with the exception of extremely thick lesions. Repeat treatments may be necessary. Curettage can be performed with or without electrocautery after administration of local anesthesia 3. Shave excision provides good cosmesis; excisional biopsy should be reserved for lesions that are suspicious for melanoma 4. Topical steroids can be used on irritated seborrheic keratoses for symptomatic relief.

The Leser-Trélat sign is the sudden onset or increase in the number of seborrheic keratoses as a result of an underlying internal malignancy, usually an adenocarcinoma of the stomach, colon, or breast 5. Although the condition is rare, a work-up that includes a complete history and physical examination, routine blood tests, chest radiography, mammography and Papanicolaou smear in women, prostate-specific antigen testing in men, and endoscopic studies (esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy) should be considered 6.

Figure 2. Seborrhoeic keratosis

Figure 3. Seborrhoeic keratosis

Cherry angioma (Campbell de Morgan’s spot)

Angiomas can be referred to as an angioma, a cherry angioma (if they have a classical cherry-like appearance) or Campbell de Morgan spots if there are numerous small lesions. Regardless of the terminology they all represent the same lesion and have the following appearances:

- Distribution

- May develop on any body surface but most common on the trunk

- Numbers increase from about the age of 40

- Morphology

- Soft papules and nodules

- Color – red / blue / purple

Cherry angiomas are acquired vascular lesions that occur in up to 50 percent of adults 7. The lesions tend to appear most often on the trunk and extremities and can be up to several millimeters in diameter. They are round, bright to dark red, nonblanching vascular papules (Figure 4). Cherry angiomas first occur in early adulthood and increase in number with age. They are asymptomatic and have no reported clinical consequences.

Cherry angiomas are composed of dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules. The cause is unknown; however, eruption of multiple lesions following exposure to various chemicals, including mustard gas 8 and 2-butoxyethanol 9 has been reported. Hormones also may be an etiologic factor; some pregnant women develop lesions that involute after delivery, and two women with elevated prolactin levels were reported to have developed hundreds of lesions 10.

Cherry angiomas are treated for cosmesis. Options include laser treatment, electrodesiccation of typical lesions, and excision of larger lesions. Cryotherapy is not effective.

Figure 4. Cherry angioma

Figure 5. Campbell de Morgan spots

Dermatofibroma

Dermatofibroma also called a cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma, is a common benign fibrous nodule (idiopathic benign proliferation of fibroblasts) that most often arises on the skin of the lower legs. Dermatofibromas are nodules derived from mesodermal and dermal cells 11. Dermatofibromas may develop at any cutaneous site and range in size from 3 to 10 mm. They are four times more common in women, and most develop between 20 and 50 years of age 12. Dermatofibromas are usually asymptomatic, although itch (pruritus) and tenderness can be present. Dermatofibromas appear gradually over months and may persist for years. Although multiple dermatofibromas may be present, large numbers (15 or more) are rare. A multiple eruptive variant occurs in only 0.3% of patients, many of whom are immunocompromised (classically, those with human immunodeficiency virus infection or systemic lupus erythematosus) 13.

It is unclear whether they are true neoplasms or fibrous reactions to minor trauma, insect bites, viral infections, ruptured cysts, or folliculitis 3. The nodules can be found anywhere on the body, but most commonly appear on the anterior surface of the lower legs. Dermatofibromas are firm, raised papules, plaques, or nodules that vary in size from 3 to 10 mm in diameter (Figure 6). They range in color from brown to purple, red, yellow, and pink 14.

Multiple dermatofibromas (i.e., more than 15) on a person have been described as being associated with autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, or immuno-compromisation 15. Usually asymptomatic, diagnosis of dermatofibromas is based on the characteristic appearance of firm, raised, papules or nodules, ranging from tan to reddish brown and Fitzpatrick’s sign, which is the dimpling or retraction of the lesion beneath the skin with lateral compression (Figure 6B) 16.

No treatment is required unless there is a change in size or color, or bleeding or irritation from trauma. A 2012 study 17 found that 73% of patients who underwent laser ablation reported satisfaction with the results.

Treatment should also be considered for cosmetic reasons or for histologic diagnosis. Dermatofibromas can be confused with melanomas, so histologic diagnosis is necessary when the physician is unsure of the clinical diagnosis. Because of the dermal location of the nodules, excisional biopsy is superior to shave biopsy to ensure clear histology and complete removal of the lesion 3. The draw-back to excisional biopsy is scar formation, especially because most dermatofibromas are seen on the thin skin of the anterior lower legs. Punch biopsy also can be used. Cryosurgery is an option for a less invasive treatment, which may not completely destroy the lesion but may improve its cosmetic appearance 18.

Figure 6. Dermatofibroma

Sebaceous Hyperplasia (Senile Hyperplasia)

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a benign disorder of the sebaceous glands that is common in middle-aged and elderly adults. In patients with rare familial forms, the condition begins during puberty. Sebaceous hyperplasia consists of soft, pale yellow, dome-shaped shiny bumps on the forehead or cheeks, or near hair follicles, some of which are centrally umbilicated (Figure 7) 19. There may be single or multiple lesions, commonly occurring on the forehead, cheeks, and nose, most lesions are 1 to 4 mm in diameter, but have been documented up to 5 cm in size 20. Sebaceous hyperplasia also can occur on the vulva. Except for cosmesis, the condition has no clinical significance; however, the lesions are sometimes confused with early basal cell carcinomas. With its characteristic mosaic appearance, the surface of sebaceous hyperplasia is generally less uniform than that of basal cell carcinomas. Histologically, lesions consist of enlarged mature lobules of sebocytes around a central duct. It is important to rule out basal cell carcinoma, which is generally red or pink and increasing in size. Inspection of any surface vessels will show a haphazard arrangement in basal cell carcinoma, whereas the vessels in sebaceous hyperplasia occur only between lobules.

Sebaceous hyperplasia is harmless and does not require any treatment, although patients may request removal of lesions for cosmetic reasons or because of concerns about malignancy. Therapeutic options include cryosurgery, phototherapy, shave excision, laser ablation, electrodesiccation with curettage, chemical cautery, or oral isotretinoin for widespread lesions 21. When the lesions are severe, extensive or disfiguring, oral isotretinoin is effective in clearing lesions but these may recur when treatment is stopped. In females, antiandrogens may help improve the appearance.

Figure 7. Sebaceous hyperplasia

Keratoacanthoma

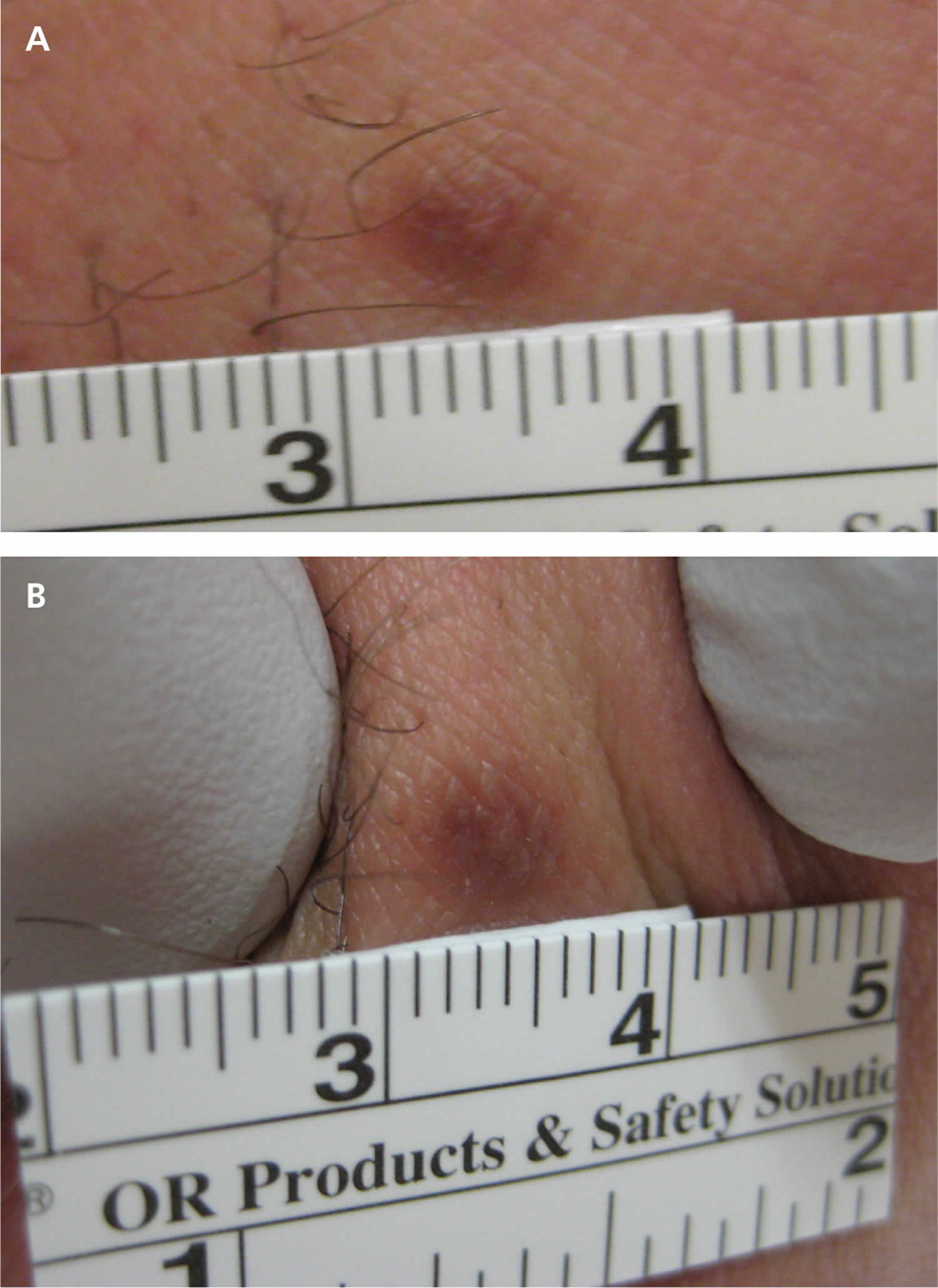

Keratoacanthomas are rapidly growing skin lesions that occur primarily on sun-damaged skin in older persons. Keratoacanthomas are rapidly growing, squamoproliferative benign tumors that resemble squamous cell carcinoma. Keratoacanthomas begin as round, firm, reddish or skin-colored papules over two to four weeks to a size of 2 cm or more that develop into dome-shaped nodules with a keratin-filled crater (Figure 8). It grows for a few months; then it may shrink and resolve by itself. The papule often develops an umbilicated, keratinous core. After four to six months, the lesion involutes with expulsion of the core, often leaving a hypopigmented scar if not excised early in its course 22. The majority of lesions involve the face and upper extremities, although they frequently occur on the lower extremities, especially in women 23.

Keratoacanthomas are usually solitary, but multiple lesions may be present. Keratoacanthoma is considered to be a variant of the keratinocyte or non-melanoma skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). As it cannot be clinically reliably distinguished from more severe forms of skin cancer, keratoacanthomas are usually treated surgically.

Keratoacanthoma may start at the site of a minor injury to sun-damaged and hair-bearing skin. At first, it may appear as a small pimple or boil and may be squeezed but is found to have a solid core filled with keratin (scale). It then proliferates, and it may be up to 2cm in diameter by the time it is brought to the attention of the doctor.

The cause of keratoacanthomas is uncertain. Possible causative agents include sun exposure, ultraviolet light, cigarette smoking, human papillomavirus infection, genetic factors, trauma, chemical carcinogens and prolonged contact with coal tar derivatives 22.

There is long-standing controversy over whether keratoacanthomas are benign, spontaneously self-limited tumors or a variant of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma that have the potential for metastasis 24. Keratoacanthomas share histopathologic characteristics that make them difficult to distinguish from squamous cell carcinoma. Shave biopsy may be inadequate to distinguish the conditions, whereas punch biopsy may be adequate because it obtains deeper tissue. Because no clinical or pathologic features can reliably differentiate keratoacanthoma from squamous cell carcinoma, early simple excision of lesions is recommended, with margins of 3 to 5 mm. Mohs micrographic surgery may be considered if tissue sparing is desired 25.

Medical treatment (systemic retinoids or intralesional injections of methotrexate, fluorouracil, or bleomycin) is reserved for nonsurgical candidates, patients with multiple lesions, and those with lesions on inoperable sites 26.

If keratoacanthoma recurs, it should be treated again.

Patients with keratoacanthomas are at risk of further similar lesions and other skin cancers.

Figure 8. Keratoacanthoma

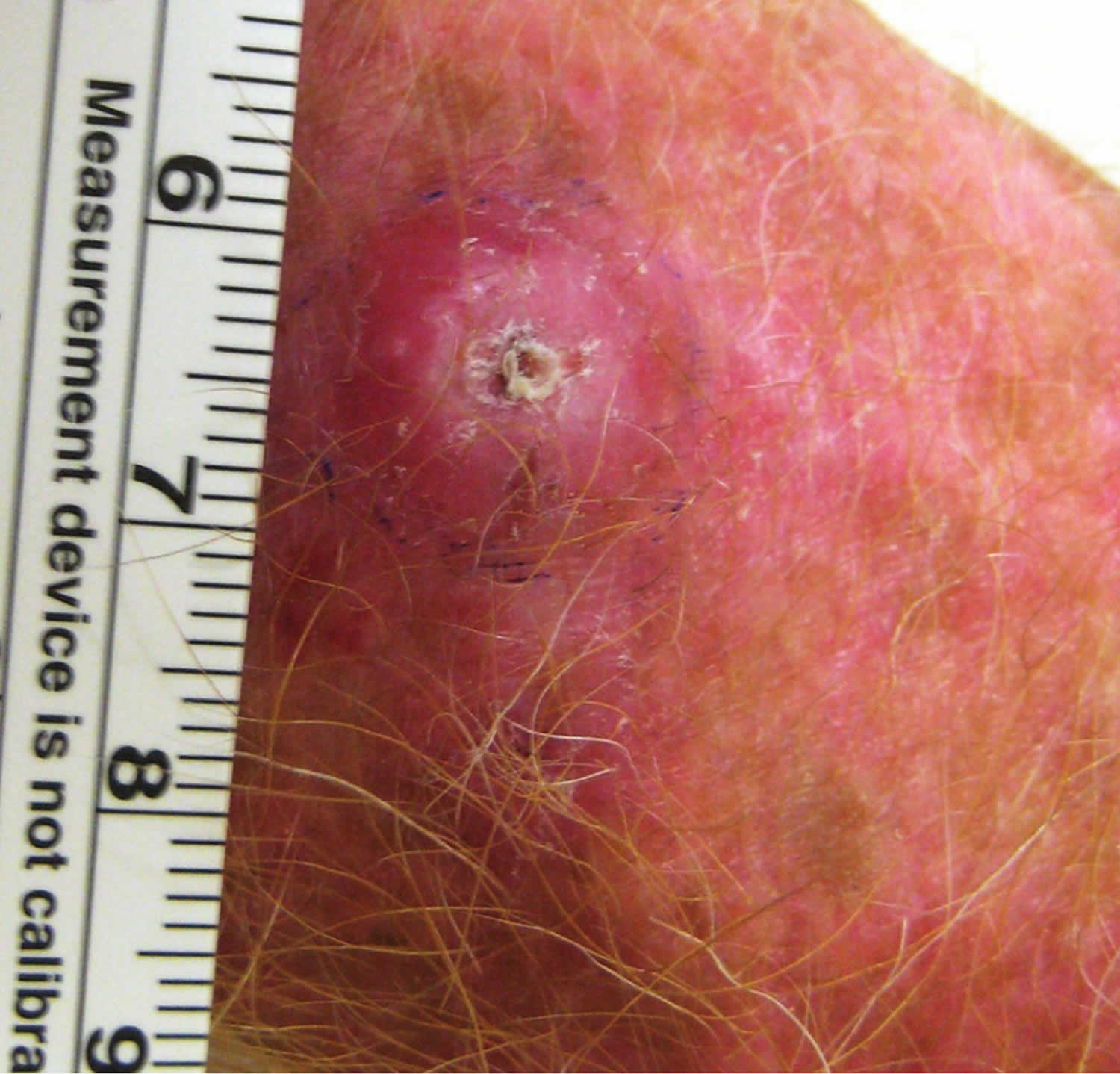

Pyogenic granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma also called lobular capillary hemangioma, granuloma pyogenicum or granuloma telangiectaticum, is a relatively common rapidly growing nodules (reactive proliferation of capillary blood vessels) that bleeds easily. Their name is a misnomer, as these lesions are neither pyogenic nor granulomas. Pyogenic granuloma presents as a shiny red lump with a raspberry-like or minced meat-like surface. Although they are benign, pyogenic granulomas can cause discomfort and profuse bleeding.

Pyogenic granulomas are an acquired benign tumor often found on mucous membranes. Pyogenic granulomas tend to occur on the head or neck, or at sites of previous penetrating trauma. Pyogenic granuloma affects people of all races. Pyogenic granuloma rarely occurs in children less than 6 months old but is common in children and young adults and women are affected more often than men because of the relationship with pregnancy. Approximately 2% of women develop a mucosal lesion in the late first to second trimester of pregnancy 27.

Pyogenic granulomas may go away on their own, particularly those associated with pregnancy. If due to a drug, they usually disappear when the drug is stopped.

Pyogenic granuloma is usually diagnosed clinically because of its typical time course and appearance. The differential diagnosis includes Spitz nevi, amelanotic melanoma, and squamous or basal cell carcinoma.

Histology confirms the diagnosis, especially if a form of skin cancer such as amelanotic melanoma is in the differential diagnosis. Pyogenic granuloma reveals a lobular collection of blood vessels within inflamed tissue.

Pyogenic granulomas are usually removed because of their rapid growth and tendency to bleed.

There are several methods used to remove pyogenic granuloma:

- Surgical excision

- Curettage and cauterisation: the lesion is scraped off with a curette and the feeding blood vessel cauterised to reduce the chances of re-growth.

- Laser surgery can be used to remove the lesion and burn the base, or a pulse dye laser may be used to shrink small lesions.

- Cryotherapy may be suitable for small lesions.

- Chemical cauterisation using silver nitrate is effective for small lesions.

- Imiquimod cream has been reported to be effective and may be particularly useful in children.

- Experimentally, topical 1% propranolol ointment has proved effective when used early in children with pyogenic granuloma 28.

Recurrence after treatment is common because feeding blood vessels extend deep into the dermis in a cone-like manner. In these cases, the most effective method of removal is to completely cut out the affected area (excision), which is then closed with stitches.

Treatment options include shave excision with electrodesiccation of the base, and laser ablation (Figure 9) 29.

Figure 9. Pyogenic granuloma

Footnote: A red, nodular pyogenic granuloma (A) before treatment, and (B) after laser ablation

Epidermal inclusion cyst

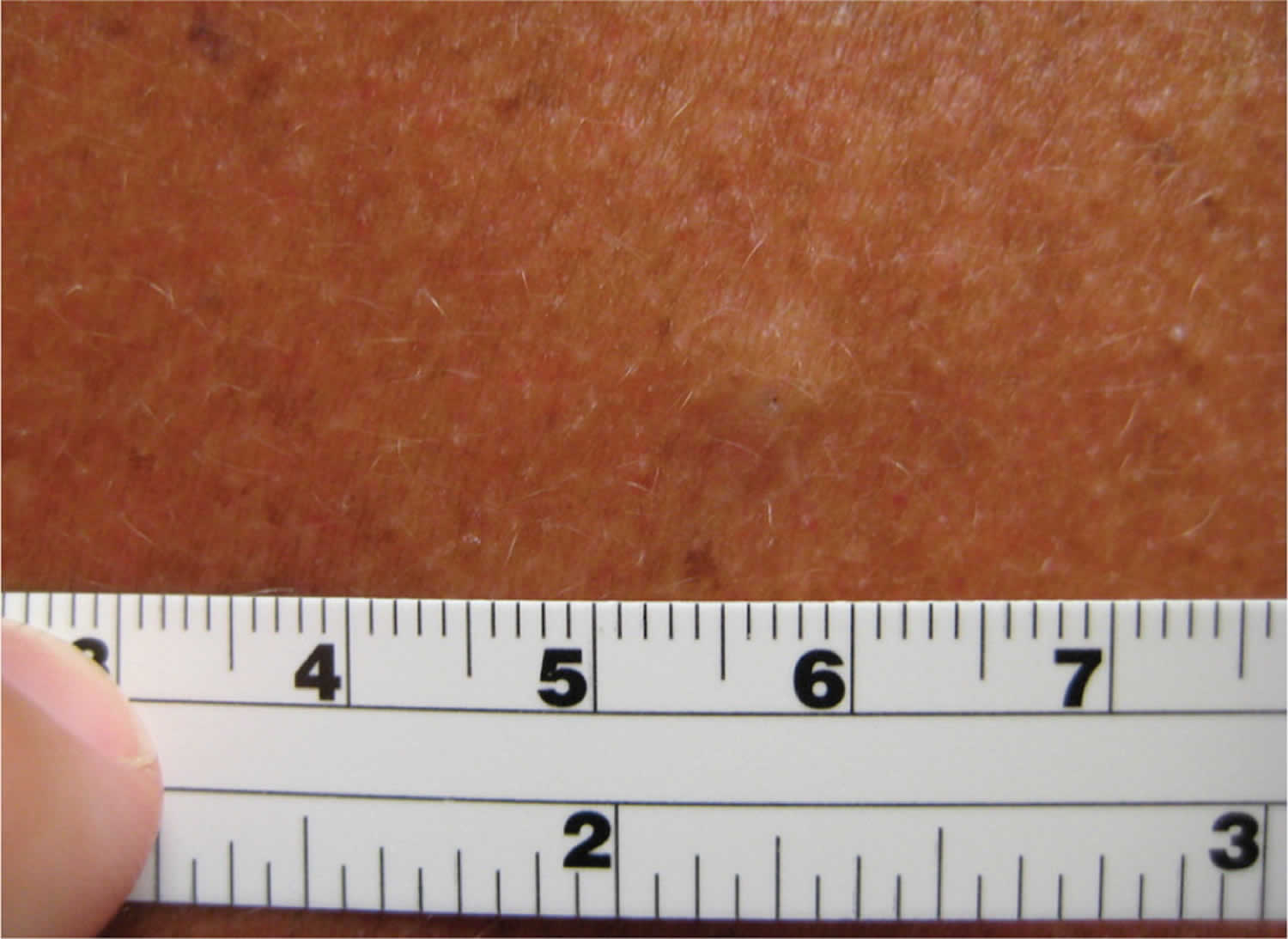

Epidermal inclusion cyst also called epidermoid cyst, is the most common type of cutaneous cyst. Epidermal inclusion cysts are discrete nodules resulting from the implantation and proliferation of epidermal elements within the dermis. However, they display no sebaceous component and are not truly sebaceous cysts. Epidermoid cysts typically present on the head, neck, back, or chest, and may remain stable for years or may grow rapidly over time. The cyst is filled with keratin and lined with stratified squamous epithelium. Spontaneous inflammation and rupture of the cyst wall into the dermis can occur, with significant involvement of surrounding tissue. The pus can either drain from the surface or be slowly resorbed. There is no way to predict which lesions will remain quiescent or become larger or inflamed. Infected cysts tend to be larger, more erythematous, and more painful than sterile inflamed cysts.

Multiple epidermal inclusion cysts are associated with Gardner syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition associated with colon cancer. Cysts that are unusual in number or location (e.g., fingers, toes) warrant screening for colon cancer. Malignancies (e.g., basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, squamous cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides, melanoma in situ) can develop in cysts, but this is rare 30.

Diagnosis of epidermal inclusion cysts is based on appearance and palpation of a discrete, freely movable cyst or nodule. Careful inspection often reveals a central punctum (Figure 10). Treatment is unnecessary unless desired by the patient, and can be accomplished via simple excision with removal of the cyst and cyst wall 31. Indications for excision include cosmesis, pain, and recurrent infection. Inflamed or ruptured cysts often resolve spontaneously without therapy, although they tend to recur. Intralesional steroid injections can hasten resolution of inflamed cysts and should be followed by interval excision 32.

Acutely inflamed, fluctuant cysts should be incised and drained. Destruction of the wall decreases the risk of cyst recurrence and drainage is enhanced with gauze packing. Use of antibiotics is not necessary, unless a concurrent cellulitis exists. Any child with sebaceous cysts or any adult with sebaceous cysts in uncommon areas may have Gardner’s syndrome, a variation of familial adenomatous polyposis exhibiting sebaceous cysts, intestinal polyps, osteomas, and fibromatosis 33.

Figure 10. Epidermal inclusion cyst

Warts

A viral wart is a very common growth of the skin caused by infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). A wart is also called a verruca, and warty lesions may be described as verrucous. Cutaneous viral warts have a hard, keratinous surface. A tiny black dot may be observed in the middle of each scaly spot, due to an intracorneal hemorrhage.

Viral warts are very widespread in people with the rare inherited disorder epidermodysplasia verruciformis.

Malignant change is rare in common warts and causes verrucous carcinoma.

Oncogenic strains of HPV, the cause of some anogenital warts and warts arising in the oropharynx, are responsible for intraepithelial and invasive neoplastic lesions including cervical, anal, penile and vulval cancer.

Warts are particularly common in:

- School-aged children, but they may arise at any age

- Eczema, due to a defective skin barrier

- People who are immune-suppressed with medications such as azathioprine or ciclosporin or with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. In these patients, warts may never disappear — despite treatment.

Warts are due to infection by the human papillomavirus (HPV), a DNA virus. More than 100 HPV subtypes are known, giving rise to a variety of presentations. Infection occurs in the superficial layers of the epidermis, causing proliferation of the keratinocytes (skin cells) and hyperkeratosis — the wart. The most common subtypes of HPV are types 2, 3, 4, 27, 29, and 57.

HPV is spread by direct skin-to-skin contact or autoinoculation. This means if a wart is scratched or picked, the viral particles may be spread to another area of skin. The incubation period can be as long as twelve months.

Clinical features of viral warts

- Common wart: Common warts present as papules with a rough, papillomatous and hyperkeratotic surface ranging in size from 1 mm to larger than 1 cm. They arise most often on the backs of fingers or toes, around the nails—where they can distort nail growth—and on the knees. Sometimes they resemble a cauliflower; these are known as butcher’s warts.

Plantar wart: Plantar warts (verrucas) include tender inwardly growing and painful ‘myrmecia’ on the sole, and clusters of less painful mosaic warts. Plantar epidermoid cysts are associated with warts. Persistent plantar warts may rarely be complicated by the development of verrucous carcinoma. - Plane wart: Plane warts have a flat surface. The most common sites are the face, hands and shins. They are often numerous. They may be inoculated by shaving or scratching so that they appear in a linear distribution (pseudo-Koebner response). Plane warts are mostly caused by HPV types 3 and 10.

- Filiform wart: Filiform warts are on a long stalk like a thread. They commonly appear on the face. They are also described as digitate (like a finger).

- Mucosal wart: Oral warts can affect the lips and even inside the cheeks, where they may be called squamous cell papillomas. They are softer than cutaneous warts. See also anogenital warts.

Viral warts are diagnosed clinically and tests are rarely needed. A dermatoscopic examination is sometimes helpful to distinguish viral warts from other verrucous lesions such as seborrhoeic keratosis and skin cancer. Sometimes, viral warts are diagnosed on skin biopsy. The histopathological features of verruca vulgaris differ from that of plane warts.

Many people don’t bother to treat viral warts because treatment can be more uncomfortable than warts —they are hardly ever a serious problem. Warts that are very small and not troublesome can be left alone, and in some cases, they will regress on its own.

However, warts may be painful, and they often look ugly so cause embarrassment.

To get rid of them, you have to stimulate your body’s immune system to attack the wart virus. Persistence with the treatment and patience is essential!

Topical treatment

Topical treatment includes wart paints containing salicylic acid or similar compounds, which work by removing the dead surface skin cells.

The paint is applied once daily. Treatment with wart paint usually makes the wart smaller and less uncomfortable; 70% of warts resolve within twelve weeks of daily applications.

- Soften the wart by soaking in a bath or bowl of hot soapy water.

- Rub the wart surface with a piece of pumice stone or emery board.

- Apply wart paint or gel accurately, allowing it to dry.

- Cover with plaster or duct tape.

If the wart paint makes the skin sore, stop treatment until the discomfort has settled, then recommence as above. Take care to keep the chemical off normal skin.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is repeated at one to two–week intervals. It is uncomfortable and may result in blistering for several day or weeks. Success is in the order of 70% after 3–4 months of regular freezing.

A hard freeze using liquid nitrogen might cause a permanent white mark or scar. It can also cause temporary numbness.

An aerosol spray with a mixture of dimethyl ether and propane (DMEP) can be purchased over the counter to freeze common and plantar warts. Read and follow the instructions carefully.

Combining immunotherapy with cryotherapy reduces the number of cryotherapy sessions.

Electrosurgery

Electrosurgery (curettage and cautery) is used for large and resistant warts. Under local anaesthetic, the growth is pared away and the base burned. The wound heals in two weeks or longer; even then 20% of warts can be expected to recur within a few months. This treatment leaves a permanent scar.

Other treatments

Other experimental treatments for recurrent, resistant or extensive warts include:

- Topical retinoids, such as tretinoin cream or adapalene gel

- The immune modulator, imiquimod cream

- Fluorouracil cream

- Bleomycin injections

- Oral retinoids

- Pulsed dye laser destruction of feeding blood vessels

- Photodynamic therapy

- Laser vaporisation

- H2 receptor antagonists

- Oral zinc oxide and zinc sulfate

- Applications of raw garlic or tea tree oil

- Immune stimulation using diphencyprone, or squaric acid

- Immunotherapy with Candida albicans or tuberculin PPD

- Hypnosis

- Hyperthermia, for example, using a heat patch

- Occlusion with duct tape.

Figure 11. Viral wart

How to diagnose benign skin tumors

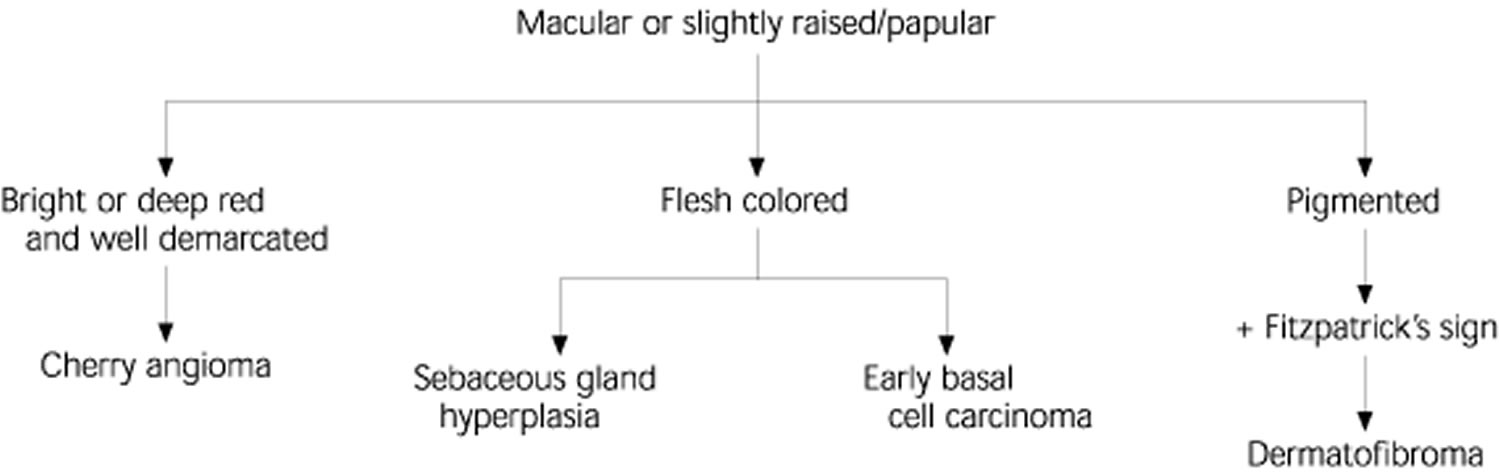

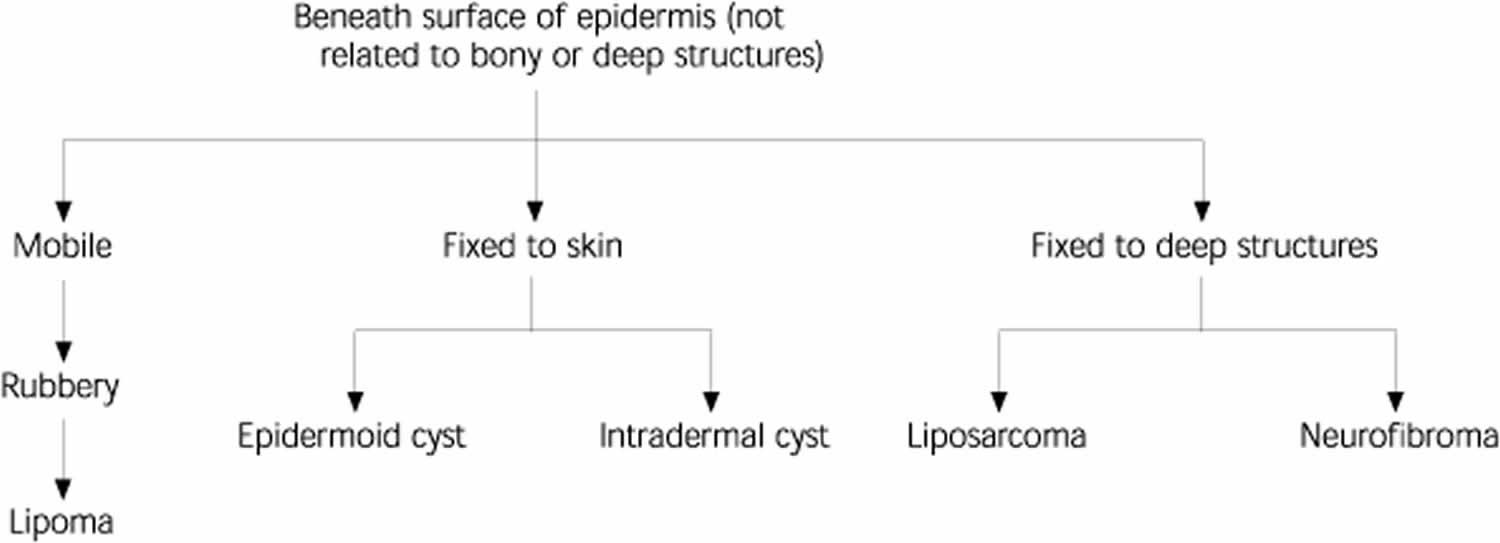

To accurately diagnose and treat benign skin lesions is an important skill your family physician should possess. Options for evaluating patients with benign skin tumors can be categorized according to the morphologic characteristics of each lesion: macular or slightly raised/papular (Figure 1), papular (Figure 2), or subepidermal (Figure 3).

Figure 11. Algorithm for the diagnosis of benign skin tumors (macular or slightly raised/papular)

Footnote: Selected common skin tumors included. Many other less common entities exist.

[Source 11 ]Figure 12. Algorithm for the diagnosis of benign papular skin tumors

Footnote: Selected common skin tumors included. Many other less common entities exist.

[Source 11 ] References- Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174(4):180–183.

- Tamega AA, Aranha AM, Guiotoku MM, Miot LD, Miot HA. Association between skin tags and insulin resistance [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(1):25–31.

- Pariser RJ. Benign neoplasms of the skin. Med Clin North Am. 1998;82:1285–307.

- Scott MA. Benign cutaneous neoplasms. Prim Care. 1989;16:645–63.

- Schwartz RA. Sign of Leser-Trelat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:88–95.

- Heaphy MR Jr, Millns JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trelat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2 Pt 2):386–90.

- Plunkett A, Merlin K, Gill D, Zuo Y, Jolley D, Marks R. The frequency of common nonmalignant skin conditions in adults in central Victoria, Australia. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:901–8.

- Firooz A, Komeili A, Dowlati Y. Eruptive melanocytic nevi and cherry angiomas secondary to exposure to sulfur mustard gas [Letter]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:646–7.

- Raymond LW, Williford LS, Burke WA. Eruptive cherry angiomas and irritant symptoms after one acute exposure to the glycol ether solvent 2-butoxyethanol. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40:1059–64.

- Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular proliferation. Part II. Hyperplasias and benign neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:887–919.

- Common Benign Skin Tumors. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Feb 15;67(4):729-738. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/0215/p729.html

- Diagnosing Common Benign Skin Tumors. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Oct 1;92(7):601-607. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/1001/p601.html

- Massone C, Parodi A, Virno G, Rebora A. Multiple eruptive dermatofibromas in patients with systemic lupus erythematous treated with prednisone. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(5):279–281.

- Ferrari A, Soyer HP, Peris K, Argenziano G, Mazzocchetti G, Piccolo D, et al. Central white scarlike patch: a dermatoscopic clue for the diagnosis of dermatofibroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1123–5.

- Lu I, Cohen PR, Grossman ME. Multiple dermatofibromas in a woman with HIV infection and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(5 Pt 2):901–3.

- Meffert JJ, Peake MF, Wilde JL. ‘Dimpling’ is not unique to dermatofibromas. Dermatology. 1997;195:384–6.

- Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Segura-Palacios JM, de Daniel-Rodríguez C, Jiménez-Gómez N, Ballester-Martínez A. Dermatofibromas treated with pulsed dye laser: clinical and dermoscopic outcomes. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14(2):98–101.

- Lanigan SW, Robinson TW. Cryotherapy for dermatofibromas. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1987;12:121–3.

- Bader RS, Scarborough DA. Surgical pearl: intralesional electrodesiccation of sebaceous hyperplasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 Pt 1):127–8.

- Czarnecki DB, Dorevitch AP. Giant senile sebaceous hyperplasia [Letter]. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1101

- Yu C, Shahsavari M, Stevens G, Liskanich R, Horowitz D. Isotretinoin as monotherapy for sebaceous hyperplasia. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(6):699–701.

- Manstein CH, Frauenhoffer CJ, Besden JE. Keratoacanthoma: is it a real entity?. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;40:469–72.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1–19.

- Karaa A, Khachemoune A. Keratoacanthoma: a tumor in search of a classification. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(7):671–678.

- Shriner DL, McCoy DK, Goldberg DJ, Wagner RF Jr. Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(1):79–97.

- Kirby JS, Miller CJ. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):689–702.

- Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(1):1–19.

- Neri I, Baraldi C, Balestri R, Piraccini BM, Patrizi A. Topical 1% propranolol ointment with occlusion in treatment of pyogenic granulomas: An open-label study in 22 children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(1):117-120. doi:10.1111/pde.13372

- Gilmore A, Kelsberg G, Safranek S. Clinical inquiries. What’s the best treatment for pyogenic granuloma? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(1):40–42.

- Swygert KE, Parrish CA, Cashman RE, Lin R, Cockerell CJ. Melanoma in situ involving an epidermal inclusion (infundibular) cyst. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29(6):564–565.

- Crile G Jr. Thirteen shortcuts in office surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 1975;55:1025–9.

- Zuber TJ. Minimal excision technique for epidermoid (sebaceous) cysts. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(7):1409–1412, 1417–1418,1420.

- Habif TP. Benign skin tumors. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. 3d ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996:627–48.