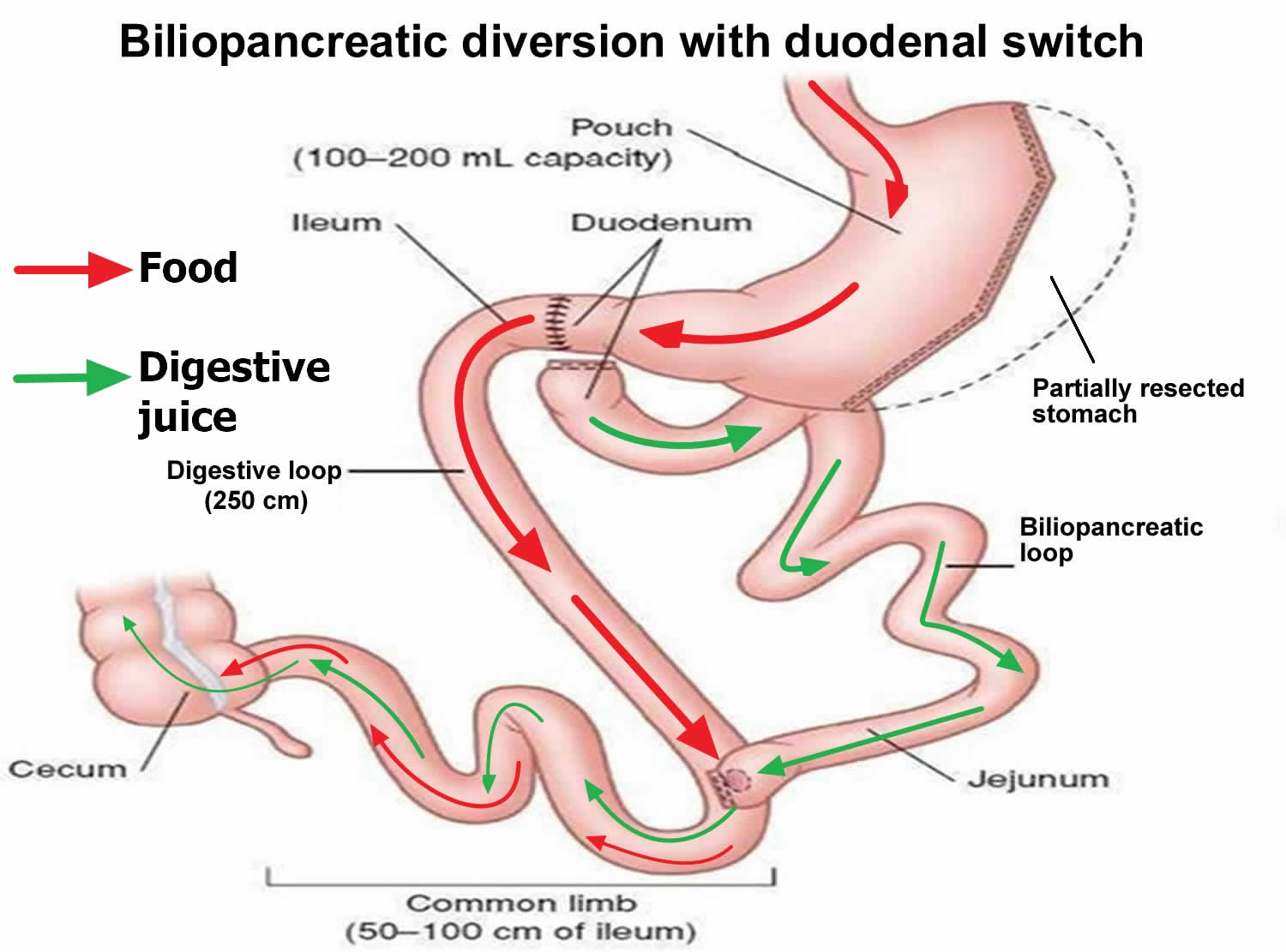

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch also known as the duodenal switch is a type of surgery to cause weight loss. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch begins with creation of a tube-shaped stomach pouch (shaped like a banana) similar to the sleeve gastrectomy. The tube-shaped stomach pouch makes patients eat less food. Following creation of the sleeve-like stomach, the first portion of the small intestine is separated from the stomach. A part of the small intestine is then brought up and connected to the outlet of the newly created stomach, so that when you eat, the food goes through the sleeve pouch and into the latter part of the small intestine. The food stream bypasses roughly 75% of the small intestine. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch resembles the gastric bypass, where more of the small intestine is not used. This results in a significant decrease in the absorption of calories and nutrients. Patients must take vitamins and mineral supplements after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery. Even more than gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch affects intestinal hormones in a manner that reduces hunger, increases fullness and improves blood sugar control. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch can cause a lot of weight loss. It can cause more weight loss than a gastric bypass or a sleeve gastrectomy. The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is considered to be the most effective approved weight loss surgery for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in patients with obesity 1.

There are currently two different forms of duodenal switch in practice. The original form is called the biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch (or sometimes, the gastric reduction duodenal switch). This is the version with the most history and research behind it. The newer version, the loop duodenal switch, was developed to simplify the procedure and reduce complications.

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is mostly done as a keyhole procedure (laparoscopic procedure), in which there are a number of small cuts in your abdomen, under general anesthesia. Through these small cuts, the surgeon can insert thin tools and a small scope attached to a camera that projects images onto a video monitor. Laparoscopic surgery has fewer risks than open surgery and may cause less pain and scarring. Recovery may also be faster with laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. But sometimes, open surgery with larger cuts is needed. Open biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch involves a single large cut in your abdomen may be a better option than laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch for certain people. You may need open surgery if you have a high level of obesity, had stomach surgery before, or have other complex medical problems.

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is done in the hospital. The length of your hospital stay will depend on your recovery and which procedure you’re having done. When performed laparoscopically, your hospital stay may last around two days.

After a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, it may be possible to lose 70 to 80 percent of your excess weight within two years. However, the amount of weight you lose also depends on your change in lifestyle habits.

In addition to weight loss, a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch may improve or resolve conditions often related to being overweight, including:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Type 2 diabetes

- Stroke

- Infertility

A biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch can also improve your ability to perform routine daily activities, which could help improve your quality of life.

- The advantages of the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure are 2:

- among the best results for improving obesity. Topart P. et al. 3 and Sethi et al. 4 reported excellent weight loss results after a follow-up of 2, 5 and 10 years.

- affects bowel hormones to cause less hunger and more fullness after eating;

- it is the most effective procedure for treatment of type 2 diabetes with obesity 5, 1

- The disadvantages of the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure are 2, 3, 4:

- has slightly higher complication rates than other procedures;

- highest malabsorption and greater possibility of vitamins and micro-nutrient deficiencies;

- reflux and heart burn can develop or get worse;

- risk of looser and more frequent bowel movements;

- more complex surgery requiring more operative time.

While a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is very effective for weight loss and the reversal of obesity-related comorbidities, it has more risks, including protein malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies and it’s more technically complex to perform with the operation being time consuming 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure is the least-common weight-loss procedure performed in the United States 13, 14, 15. The most common types of weight loss surgery in United States are gastric sleeve surgery (sleeve gastrectomy) around 53.8%, followed by gastric bypass (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) 23.1%; laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (gastric banding) 5.7% with biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch at 0.6% 13, 14, 15.

You may be a good candidate for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch if you are an adult who has extreme obesity (Body Mass Index (BMI) > 40 kg/m²) or super obesity (Body Mass Index (BMI) > 50 kg/m²) and you have not been able to lose your excess weight, or you keep gaining back weight you have lost using non-surgical methods such as diet and exercise or medications 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch may also be offered to people who are obese (BMI over 35 kg/m²) and who have other serious health problems like type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure or severe obstructive sleep apnea. It has also been shown that the biliopancreatic bypass with duodenal switch has a better effect on type 2 diabetes and reduction of hyperlipidemia then other weight loss procedures 21. The caveat is that this procedure requires an adequate follow-up program because there is an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies compared with the other weight loss procedures.

In general, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch could be an option for you if 22, 23, 24, 25:

- Your body mass index (BMI) is 40 kg/m² or higher (extreme obesity). Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is recommended for super obese people with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 50 kg/m² 17, 18, 19, 20

- Your BMI is 35 to 39.9 kg/m² (obesity), and you have a serious weight-related health problem, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, severe obstructive sleep apnea, stroke, high cholesterol, lung disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), asthma or some other breathing problems.

- Patients who fail operative treatment with Roux en-Y gastric bypass surgery and gastric sleeve surgery, biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch should be considered 20, 26

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a measure of obesity used to determine who are good candidates for weight-loss surgery. Body Mass Index (BMI) measures body fat based on your weight in relation to your height.

- The formula for Body Mass Index (BMI) = weight (kg) / [height (m)]²

Body Mass Index (BMI) is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

- Example: Weight = 68 kg, Height = 165 cm (1.65 m)

- Calculation: 68 ÷ (1.65)² = 24.98 kg/m² = BMI

You can also use an online BMI calculator:

- For Adults go here: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/english_bmi_calculator/bmi_calculator.html

- For Children go here: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/bmi/calculator.html

A biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is typically done only after you’ve tried to lose weight by non-surgical alternatives such as improving your diet and exercise habits. The first step is usually to try changes to what you eat and drink, and what daily activity and exercise you do. There are some medicines that can help people lose weight. Surgery is usually thought about only after these other options have been tried.

For people with a BMI of 35 kg/m² or higher, obesity can be hard to treat with diet and exercise alone, so health care professionals may recommend weight-loss surgery. For people with a BMI of 30-35 kg/m² who have type 2 diabetes that is difficult to control with medications and lifestyle changes, weight-loss surgery may be considered as a treatment option.

Weight-loss surgery also may be an option to consider if you have serious health problems related to obesity, such as type 2 diabetes or sleep apnea. Weight-loss surgery can improve many of the medical conditions linked to obesity, especially type 2 diabetes 27, 28.

But a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch isn’t for everyone who is severely overweight. You likely will have an extensive screening process to see if you qualify.

You must also be willing to make permanent changes to lead a healthier lifestyle both before and after surgery. You may be required to participate in long-term follow-up plans that include monitoring your nutrition, your lifestyle and behavior, and your medical conditions.

Before your biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch procedure, you will meet with several health care professionals, such as an internist, a dietitian, a psychiatrist or psychologist, and a bariatric surgeon.

- The internist will ask about your medical history, perform a thorough physical exam, and order blood tests. If you smoke, you may benefit from stopping smoking at least 6 weeks before your surgery.

- Preoperative nutritional assessment recommendations 29, 30:

- All people should have a comprehensive nutritional assessment prior to weight loss surgery

- Check full blood count including hemoglobin, ferritin, folate and vitamin B12 levels

- Check serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels

- Check serum calcium levels

- Check serum/plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels

- Seek advice from a specialist with expertise in primary hyperparathyroidism if primary hyperparathyroidism is suspected

- Consider checking serum vitamin A levels in individuals going forward for malabsorptive procedures such as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch or where vitamin A deficiency may be suspected

- Consider checking serum zinc, copper and selenium levels in individuals going forward for malabsorptive procedures such as biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch or if a deficiency is suspected

- Routinely screen HbA1c, lipid profile, liver and kidney function tests and treat as necessary

- Treat and correct nutritional deficiencies preoperatively as individuals have an increased risk of deficiencies postoperatively

- Preoperative nutritional assessment recommendations 29, 30:

- The dietitian will explain what and how much you will be able to eat and drink after surgery and help you prepare for how your life will change after surgery.

- The psychiatrist or psychologist may assess you to see if you are ready to manage the challenges of weight-loss surgery.

- The surgeon will tell you more about the surgery, including how to prepare for it and what type of follow-up you will need.

These health care professionals also will advise you to become more active and adopt a healthy eating plan before and after surgery. Many weight loss surgical centers recommend that people follow a low calorie or low carbohydrate diet immediately prior to surgery to reduce the size of their liver 31. As these diets are not always nutritionally complete, a multivitamin and mineral supplement are needed 32

Losing weight and bringing your blood glucose, also known as blood sugar, levels closer to normal before surgery may lower your chances of having surgery-related problems.

Some weight-loss surgery programs have groups you can attend before and after surgery to help answer questions about the surgery and offer support.

Lastly, check with your health insurance plan or your regional Medicare or Medicaid office to find out if your policy covers weight-loss surgery.

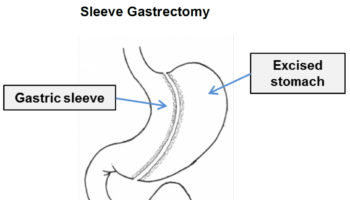

Figure 1. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

[Source 33 ]Where to find a weight loss surgeon near me?

To find a board certified weight loss surgeon (the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery) please go here https://asmbs.org/patients/find-a-provider

How much weight can I lose with a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch?

The average weight loss with a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is 80% of excess weight over a two-year period. That’s well above the average weight loss from other weight loss surgery overall, which is 50% to 60%. People who have biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery also maintain more weight loss over the long term. Studies show an average sustained weight loss of 70% of excess weight over ten years. That means that if you were 200 lbs. overweight, you would lose an average of 140 lbs., and keep it off.

How effective is biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch?

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery has a 90% success rate for weight loss. That means that 90% of people lose at least 50% of their excess weight. Most lose more. The surgery has a similar success rate for remission of related health conditions. As much as 90% of people with type 2 diabetes are able to discontinue their medications after a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Because of its higher success rate, some people who fail to lose enough weight with other weight loss surgeries choose to have revision surgery with a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch.

What is the difference between biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch vs. gastric bypass surgery?

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is similar to the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Both involve reducing your stomach (weight loss by restriction) and bypassing part of your small intestine (weight loss by malabsorption). In general, the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch leans more on malabsorption, while the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass leans more on restriction. The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch reduces the size of your stomach by about 60% to 70% (vs. 70% to 80% with the Roux-en-Y). But it also bypasses about 75% of the small intestine (vs. about 30% with the Roux-en-Y).

What is the difference between biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch vs. the gastric sleeve?

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is a two-part surgery that begins with a gastric sleeve. In fact, the sleeve gastrectomy was originally developed as the first part of the duodenal switch. The gastric sleeve procedure reduces the stomach to a small, tubular “sleeve,” about 75% of its original size. The second part of the duodenal switch goes a step further by bypassing much of the small intestine. This second part produces greater weight loss than the gastrectomy alone, but also more potential side effects.

When biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure doesn’t work

It’s possible to not lose enough weight or to regain weight after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery. This weight gain can happen if you don’t follow the recommended lifestyle changes. If you frequently snack on high-calorie foods, for instance, you may have inadequate weight loss. To help avoid regaining weight, you must make permanent healthy changes in your diet and get regular physical activity and exercise.

It’s important to keep all of your scheduled follow-up appointments after weight-loss surgery so your doctor can monitor your progress. If you notice that you aren’t losing weight or you develop complications after your surgery, see your doctor immediately.

Stomach anatomy

The stomach is a muscular J-shaped pouchlike hollow organ that hangs inferior to the diaphragm in the upper left portion of the abdominal cavity and has a capacity of about 1 liter or more (Figure 2) 34. The stomach’s shape and size vary from person to person, depending on things like people’s sex and build, but also on how much they eat.

At the point where the esophagus leads into the stomach, the digestive tube is usually kept shut by muscles of the esophagus and diaphragm (Figure 3). When you swallow, these muscles relax and the lower end of the esophagus opens, allowing food to enter the stomach. If this mechanism does not work properly, acidic gastric juice might get into the esophagus, leading to heartburn or an inflammation (Figure 3).

Thick folds (rugae) of mucosal and submucosal layers mark the stomach’s inner lining and disappear when the stomach wall is distended. The stomach receives food from the esophagus, mixes the food with gastric juice, initiates protein digestion, carries on limited absorption, and moves food into the small intestine (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Stomach

Figure 3. Gastroesophageal junction

Figure 4. Parts of the small intestine

Parts of the Stomach

The stomach has 5 parts (Figure 5):

The cardia is a small area near the esophageal opening.

The fundus, which balloons superior to the cardia, is a temporary storage area. It is usually filled with air that enters the stomach when you swallow.

The dilated body region, called the body (corpus), which is the main part of the stomach, lies between the fundus and pylorus. In the body of the stomach food is churned and broken into smaller pieces, mixed with acidic gastric juice and enzymes, and pre-digested.

The antrum – the lower portion (near the intestine), where the food is mixed with gastric juice

The pylorus is the distal portion and the last part of the stomach where it approaches the small intestine. The pyloric canal is a narrowing of the pylorus as it approaches the small intestine. At the end of the pyloric canal the muscular wall thickens, forming a powerful circular muscle, the pyloric sphincter. This muscle is a valve that controls gastric emptying.

The first 3 parts of the stomach, the cardia, fundus, and body, are sometimes called the proximal stomach. Some cells in these parts of the stomach make acid and pepsin (a digestive enzyme), the parts of the gastric juice that help digest food. They also make a protein called intrinsic factor, which the body needs to absorb vitamin B12.

The lower 2 parts, the antrum and pylorus, are called the distal stomach. The stomach has 2 curves, which form its inner and outer borders. They are called the lesser curvature and greater curvature, respectively.

Figure 5. Parts of the stomach

Stomach function

The stomach takes in food from the esophagus (gullet or food pipe), mixes it, breaks it down, and then passes it on to the small intestine in small portions. Following a meal, the mixing movements of the stomach wall aid in producing a semifluid paste of food particles and gastric juice called chyme. Peristaltic waves push the chyme toward the pylorus of the stomach. As chyme accumulates near the pyloric sphincter, the sphincter begins to relax. Stomach contractions push chyme a little at a time into the small intestine.

The rate at which the stomach empties depends on the fluidity of the chyme and the type of food present. Liquids usually pass through the stomach rapidly, but solids remain until they are well mixed with gastric juice. Fatty foods may remain in the stomach from three to six hours; foods high in proteins move through more quickly; carbohydrates usually pass through faster than either fats or proteins.

As chyme enters the duodenum (the proximal portion of the small intestine), accessory organs—the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder—add their secretions.

Gastric secretions

The mucous membrane that forms the inner lining of the stomach is thick. Its surface is studded with many small openings called gastric pits located at the ends of tubular gastric glands (Figure 6).

Gastric glands generally contain three types of secretory cells. Mucous cells, in the necks of the glands near the openings of the gastric pits, secrete mucus. Chief cells and parietal cells are in the deeper parts of the glands. The chief cells secrete digestive enzymes, and the parietal cells release a solution containing hydrochloric acid. The products of the mucous cells, chief cells, and parietal cells together form gastric juice.

Pepsin is by far the most important digestive enzyme in gastric juice. The chief cells secrete pepsin in the form of an inactive enzyme precursor called pepsinogen. When pepsinogen contacts hydrochloric acid from the parietal cells, it breaks down rapidly, forming pepsin. Pepsin begins the digestion of nearly all types of dietary protein into polypeptides. This enzyme is most active in an acidic environment, which is provided by the hydrochloric acid in gastric juice.

The mucous cells of the gastric glands (mucous neck cells) and the mucous cells associated with the stomach’s inner surface release a viscous, alkaline secretion that coats the inside of the stomach wall. This coating normally prevents the stomach from digesting itself.

Another component of gastric juice is intrinsic factor, which the parietal cells secrete. Intrinsic factor is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine. Table 1 summarizes the major components of gastric juice.

Figure 6. Stomach cells (gastric glands)

Note: Lining of the stomach. Gastric glands include mucous cells, parietal cells, and chief cells. The mucosa of the stomach is studded with gastric pits that are the openings of the gastric glands.

Table 1. Major components of Gastric Juice

| Component | Source | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Pepsinogen | Chief cells of the gastric glands | Inactive form of pepsin |

| Pepsin | Formed from pepsinogen in the presence of hydrochloric acid | A protein-splitting enzyme that digests nearly all types of dietary protein into polypeptides |

| Hydrochloric acid | Parietal cells of the gastric glands | Provides the acid environment needed for the production and action of pepsin |

| Mucus | Mucous cells | Provides a viscous, alkaline protective layer on the stomach’s inner surface |

| Intrinsic factor | Parietal cells of the gastric glands | Necessary for vitamin B12 absorption in the small intestine |

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch contraindications

The contraindications for biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch are similar to other weight loss procedures 35.

Absolute contraindications for weight loss surgery:

- Pregnancy

- Severe psychiatric illness

- Eating disorders

- Patient-related contraindications to undergo surgery (cardiovascular risk, anesthetic risk)

- Substance misuse (alcoholism)

- Severe coagulopathies (blood clotting or bleeding disorders)

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure

You will need to go through an in-depth process to be approved for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure. This is done to find out if you are ready for the surgery, and if it will help you. And you will need to find out if your health insurance plan will cover the costs of the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure. You’ll need to meet with healthcare providers such as a surgeon, a special bariatric nurse, and a dietitian with experience in biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch.

Talk with your healthcare team how to prepare for your surgery. Tell your healthcare providers about all the medicines you take. This includes over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, herbs, and other supplements. You may need to stop taking some medicines before the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure, such as blood thinners and aspirin.

How you prepare

If you qualify for a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, your health care team gives you instructions on how to prepare for surgery.

You may need to have various lab tests and exams before surgery, such as:

- Blood tests, to check your overall health

- Chest X-ray to check your lungs

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) to check your heart rhythm

You will generally also be told to:

- Stop smoking.

- Lose weight by following a special diet.

- Get counseling to discuss emotional health and disordered eating habits.

- Read educational material that will be given to you or attend classes about the procedure, expected results, and possible complications.

Tell your health care team if you:

- Have had any recent changes in your health, such as an infection or fever

- Are sensitive or allergic to any medicines, latex, tape, or anesthetic medicines (local and general)

- Have a history of bleeding disorders

- Are taking any blood-thinning (anticoagulant) medicines, including aspirin, ibuprofen, or other medicines that affect blood clotting

- Are pregnant or think you may be pregnant

- Use a CPAP or BiPAP machine for sleep apnea or another breathing disorder

Also:

- Ask a family member or friend to take you home from the hospital. You can’t drive yourself.

- Follow any directions you are given for not eating or drinking before surgery.

- Follow all other instructions from your healthcare provider.

- Ask which medicines you should stop taking before surgery and for how long, and which medicines should be taken the day of surgery.

- Bring your CPAP or BiPAP machine to the hospital on the day of your surgery.

You will be asked to sign a consent form that gives your doctor permission to do the procedure. Read the form carefully. Ask questions if something is not clear.

Food and medications

Before your surgery, give your surgeon and any other health care providers a list of all medicines, vitamins, minerals, and herbal or dietary supplements you take. You may have restrictions on eating and drinking and which medications you can take.

If you take blood-thinning medications, talk with your doctor before your surgery. Because these medications affect clotting and bleeding, your blood-thinning medication routine may need to be changed.

If you have diabetes, talk with the doctor who manages your insulin or other diabetes medications for specific instructions on taking or adjusting them after surgery.

Patients are typically placed on a low carbohydrate diet before biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery to shrink the liver as much a possible before surgery. Studies have shown that preoperative weight loss may lead to some improvements in postoperative outcomes and possibly decrease complications. Patients who can lose weight before surgery have been shown to have total weight loss following the surgery 36.

Other precautions

You may be required to start a physical activity program and to stop any tobacco use.

You may also need to prepare by planning ahead for your recovery after surgery. For instance, arrange for help at home if you think you’ll need it.

Before biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure

Before you go to the operating room, you will change into a gown and will be asked several questions by both doctors and nurses. In the operating room, you are given general anesthesia before your surgery begins. Anesthesia is medicine that keeps you asleep and comfortable during surgery.

During biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure

The specifics of your surgery depend on your individual situation and your doctor’s practices. Some surgeries are done with traditional large, or open, incisions in your abdomen, while some may be performed laparoscopically, which involves inserting instruments through multiple small incisions in your abdomen.

- The first step of a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. The first step in a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch involves removing a portion (about 80 percent) of your stomach. After making the incisions with the open or laparoscopic technique, your surgeon removes a large portion of your stomach and forms the remaining portion with staples into a narrow sleeve shaped like a banana similar to the sleeve gastrectomy. Your surgeon leaves intact the valve that releases food to the small intestine (the pyloric valve or pyloric sphincter), along with a limited portion of the small intestine that normally connects to the stomach (duodenum). This small stomach restricts the amount of food you can eat at one time.

- The second step of a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. During the second step, your surgeon makes one cut through the first part of the small intestine just below the duodenum and a second cut farther down, near the lower end of the small intestine (the ileum). Then your surgeon brings a very short length of the last part of the small intestine (the ileum) is brought up and attached to the duodenum. This is the duodenal switch. The effect is to bypass a large segment of the small intestine.

- Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is generally performed as a single procedure; however, in select circumstances, the procedure may be performed as two separate operations — sleeve gastrectomy followed by intestinal bypass once weight loss has begun.

Each part of the surgery usually takes a few hours. After surgery, you awaken in a recovery room, where medical staff monitors you for any complications.

When you eat, the food then only goes through the new stomach pouch. It empties into the last part of the small intestine (the ileum). This goes around (bypasses) a large section of the small intestine (a small segment of the duodenum and the jejunum), so that less of the food is digested. You absorb fewer calories and nutrients. This can cause a lot of weight loss. The part of the small intestine (a small segment of the duodenum and the jejunum) that has been separated is reconnected to the last part of the small intestine (the ileum). This changes the normal way that bile and digestive juices break down food. This is the biliopancreatic diversion. This cuts back on how many calories you absorb, causing still more weight loss.

After biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure

You will wake up in a recovery room. You will be given medicine to control pain. You will then be moved to a hospital room. You will be asked to get out of bed to move around within the next day. This helps prevent blood clots in your legs. You will have liquid nutrition. Your healthcare team will tell you when you’re ready to go home.

At first, you may have stomach or bowel cramping, or nausea. Tell your healthcare team if pain or nausea is severe or doesn’t improve with time. Take pain medicines as prescribed. Your healthcare team will tell you when it’s OK to shower, drive, return to work, exercise, and lift objects.

Call your surgeon or healthcare team if you have any of the following:

- A fever of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher, or as directed by your healthcare provider

- A red, bleeding, or draining incision

- Frequent or persistent nausea or vomiting

- Increased pain at an incision

- Pain or swelling in your legs

- Trouble breathing or chest pain

You will get instructions about how to adapt to your new diet after your surgery. You will likely be on liquid nutrition for a few weeks after surgery. Over time, you’ll start to eat soft foods and then solid foods. If you eat too much or too fast, you will likely have stomach pain or vomiting. You’ll learn how to know when your new stomach is full.

Your healthcare provider or nutritionist will give you more instructions about your diet. You’ll need to learn good habits like choosing healthy foods and not skipping meals. Your healthcare provider or nutritionist will also need to screen you for low levels of vitamins and nutrients.

Immediately after a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure, you may have liquids but no solid food as your stomach and intestines begin to heal. You’ll then follow a special diet plan that changes slowly from liquids to pureed foods. After that, you can eat soft foods, then move on to firmer foods as your body is able to tolerate them.

Your diet after surgery may continue to be quite restricted, with specified limits on how much and what you can eat and drink. Your doctor will recommend that you take vitamin and mineral supplements after surgery, including a multivitamin, calcium and vitamin B12. These are vital to prevent micronutrient deficiency.

You will need to take daily supplements after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery. These include:

- Vitamins A, D, and K

- Multivitamin

- Iron supplements

- Calcium supplements

- Vitamin B-12 supplements or injections

Work with your healthcare team after surgery to stay healthy. Make sure to:

- Follow the nutrition plan set up by your dietitian.

- Get regular physical activity. Start slowly and build up to more activity.

- Talk with a counselor or weight-loss surgery support group to help you adjust.

You’ll also have frequent medical checkups to monitor your health in the first several months after weight-loss surgery. You may need laboratory testing, bloodwork and various exams.

You may experience changes as your body reacts to the rapid weight loss in the first three to six months after a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, including:

- Body aches

- Feeling tired, as if you have the flu

- Feeling cold

- Dry skin

- Hair thinning and hair loss

- Mood changes

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch complications

As with any major surgery, a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch poses potential health risks, both in the short term and long term.

Risks associated with biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch are similar to any abdominal surgery and can include:

- Bleeding, which may require transfusions and additional procedures including more surgery

- Infection, such as pneumonia, intra-abdominal abscesses, or Clostridium difficile colitis, which can lead to septic shock

- Adverse reactions to anesthesia

- Allergic reactions to medicines

- Blood clots in your legs (deep vein thrombosis or DVT) that may travel to your lungs (pulmonary embolism)

- Lung or breathing problems

- Leaks from the site where the sections of the stomach, small intestine, or both are stapled or sewn together (anastomotic leak)

- Injury to your stomach, intestines, or other organs during surgery

- Injury to the spleen that may lead to removal of the spleen, which can lead to long term problems with immunity

- Heart attack

- Rhythm problems with the heart (arrhythmias)

- Stroke

- Short-term (temporary) hair loss

- Stomach cramping and diarrhea after eating fat

Rarely, complications of a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch can lead to death. In a recent meta-analysis of 361 studies including 85 048 patients overall rate of death within 30 days of weight loss surgery was found to be 0.28% 11. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch had the highest early mortality with a rate of 0.29% to 1.23% for open and 0.0% to 2.7% for laparoscopic procedures 11. Postoperative mortality is most commonly associated with pulmonary embolism, respiratory failure, and anastomotic leaks. It is important to acknowledge that biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is the procedure of choice for the most extremely obese patients; therefore it can be assumed that surgical risk in this group is higher at baseline 37. This was demonstrated in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium, a prospective multicenter observational study, which included 4776 patients analyzing 30-day outcomes after bariatric surgery. It showed that extreme values of BMI were significantly associated with increased risk of major adverse outcomes (death; venous thromboembolism; percutaneous, endoscopic, or operative reintervention; and length of stay greater than 30 days) 38.

One-year complication rates as reported in the US Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database are 4.6% after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, 10.8% after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, 14.9% after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and 25.7% after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch 39. This includes minor complications such as gastrointestinal side effects including flatulence, malodorous stools, and fatty stools (steatorrhea). Of major complications, gastrointestinal anastomotic leak is the most common, serious, early surgical complication. Hamoui et al. 40 reviewed 701 biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch cases performed over a ten-year period and reported that 5% of patients developed complications necessitating revisional surgery. Protein malnutrition was the most common indication for reoperation. A postoperative complication rate of 15% was then seen in their revisional surgery group, with wound infections being the most common complication in this group 40. Biertho et al. 10 analyzed a series of 1000 biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch patients, in which major complications occurred in 7% of patients. They showed no difference in complication rate when comparing laparoscopic to open biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Rehospitalization was required in 12.7% of patients and reoperations occurred in 6% of patients 10.

In a randomized trial of 60 patients, Sovik et al. 41 compared mean operating time, median length of stay, and complication rates between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. On average Roux-en-Y gastric bypass required 91 minutes operating time compared to 206 minutes operating time for biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Median length of stay was 2 days post-RYGB and 4 days post-biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Perioperative complication rates were comparable between groups; however this study was likely underpowered and larger studies are necessary to truly draw conclusions 41. It can not be understated that a greater volume of less complex bariatric procedures could be performed in the time that it takes to complete biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. With the overwhelming burden of obesity and need for weight loss surgical procedures mindful resource allocation is crucial. A staged procedure with biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for select patients may allow for better utilization of resources in those patients who would benefit most from this complex surgery 37.

Longer term risks and complications of a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch may include:

- Blockages in the intestines, known as bowel obstruction (scarring inside your belly that could lead to a blockage in your bowel in the future)

- Dumping syndrome, causing diarrhea, nausea or vomiting and cramping

- Gallstones

- Dehydration if you don’t drink enough fluids

- Kidney failure

- Hernia at an incision site or inside the abdomen

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- Not enough protein (protein malnutrition)

- Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch makes it hard for the body to absorb vitamins and minerals. People who have biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch may have vitamin and iron deficiency (shortage):

- Low levels of calcium and iron

- Low levels of fat-soluble vitamins such as A, D, E, and K

- Low level of thiamine (vitamin B1). This is rare but can damage the nervous system.

- These can lead to serious, long-term problems such as:

- Not enough red blood cells (anemia)

- Thinning bones (osteoporosis)

- Kidney stones

- Severe life-threatening protein malnutrition called Kwashiorkor (rare)

- Gastritis (inflamed stomach lining), heartburn, or stomach ulcers

- Stomach perforation

- Ulcers

- Ongoing vomiting from eating more than your stomach pouch can hold

- Depressed mood or other emotional issues

- Risk of acid reflux, esophagitis and hiatal hernia (caused by the stomach pushing up against the diaphragm)

- Need for more surgery to fix problems.

You may also have problems such as:

- Failure to meet your weight loss goals

- Weight regain

- Loose folds of skin that may need surgery to remove

You will need to take vitamin and mineral supplements for life. You will also need to have blood tests regularly. This is to prevent severe malnutrition and related problems. Even if you take supplements, you still may have nutrition problems and need treatment.

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch will change your eating habits for the rest of your life. Make sure you fully understand the risks and benefits for you. Your own risks and benefits may vary according to your age and your general health. Talk with your surgeon to find out what risks may apply to you.

Anastomotic leak

The incidence of a gastric or duodenal leak following biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is 1.14% vs. 1.12% for Roux en-Y gastric bypass 42. The leak site appears to be more common at the duodenoduodenal anastomosis 43. The risk of leakage from the longitudinal gastric staple line is minimal compared to the leak rate from the gastric staple line in the gastric bypass procedure. These patients may be asymptomatic, but they frequently present with rapid heart rate (tachycardia), which is usually the first sign. They can also have rapid breathing (tachypnea) and be febrile. The diagnostic test of choice for an anastomotic leak should be a CT scan with oral and IV contrast, high sensitivity, and specificity. An upper GI series can also be used, but it has a low sensitivity. If the leak is acute (<5 days), patients should return to the operating room for exploration with repair and placement of a distal feeding tube 44.

Bleeding

The reported incidence for a postoperative hemorrhage is less than 1% of all gastric bypass surgeries experience bleeding, which requires intervention or transfusion. This can present as intraluminal and extraluminal bleeding. This has likely improved due to improved staple technology. Hemorrhage is more commonly seen with laparoscopic gastric bypass over open procedures 45. Postoperative hemorrhage is treated at the surgeon’s discretion, depending on the patient’s clinical picture 46. For intraluminal bleeding, endoscopic treatment may be necessary but is not very common 46. Patients who have extraluminal bleeding who are hemodynamically unstable and unresponsive to resuscitation will need to return to the operating room for exploration and repair 46.

Nutritional deficiencies

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch is the weight loss procedure associated with the greatest perioperative malnutrition and metabolic-related complications 46. All patients need to begin supplementation postoperatively ; however there is no standardized approach to replacement and sometimes deficiencies are refractory to dietary supplements 37. Following biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch patients can consume normal nutritional meals and continue to be malnourished 47. Common nutritional deficiencies that can be seen are iron deficiency anemia, protein-calorie malnutrition, low blood calcium (hypocalcemia), deficiency of the fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E and K), vitamin B1 (thiamin), vitamin B12, and folate 47. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch has proven to be more malabsorptive compared to other weight loss surgeries; thus close follow-up and laboratory studies are essential for these patients. If a nutritional deficiency is detected, dietary supplementation is extremely important 37. Supplementation is of paramount importance; unfortunately in this patient population compliance is lacking 48.

As an example, the supplements implemented by Marceau et al. 49 in their uncontrolled case series with fifteen-year follow-up was as follows:

- Iron 300 mg,

- Calcium 500 mg,

- Vitamin D 50 000 IU,

- Vitamin A 20 000 IU,

- 1 multivitamin tablet, and

- yogurt probiotics.

Adjustments were made as appropriate; consequently severe anemia and vitamin deficiencies were uncommon 49.

Aasheim et al. 50 randomized 60 super-obese patients to receive either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch comparing 25-hydroxyvitamin D, vitamin A, and vitamin B1 up to 1 year postoperatively. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch patients had lower mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D and vitamin A concentrations, as well as a steeper decline in vitamin B1 compared to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass 50. Decreased vitamin D and calcium levels with associated secondary hyperparathyroidism have been demonstrated 51, 52, 53. Marceau et al. 49, after prospectively analyzing 33 patients utilizing iliac crest bone biopsy, bone mineral density, and biochemical investigations, proclaimed that despite serum abnormalities in vitamin D, calcium, and PTH overall bone mineral density and fracture risk were unchanged 10 years after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. A population-based retrospective cohort study out of the United Kingdom confirmed these results, concluding that bariatric surgery (60% gastric band, 29% Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 11% other—biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch was not separated) did not significantly effect fracture risk with a mean follow-up of 2.2 years 54. Additionally, facture risk was independent of the specific surgical technique. Longer-term studies are necessary to ensure that results are enduring 54. Clinically there have been case reports of biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch-related vitamin A deficiency and associated night-blindness 55, 56, post-biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch peripheral neuropathies associated with B12 deficiencies 55 and Wernicke’s encephalopathy as a result of vitamin B1 deficiencies 57, 58.

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch diet

Immediately after a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch procedure, you may have clear liquids but no solid food as your stomach and intestines begin to heal. An upper gastrointestinal study with water-soluble contrast (Gastrografin®) is routinely performed on the second postoperative day in all patients, to evaluate and document the shape, capacity and function of the stomach. You’ll then follow a special diet plan that changes slowly from liquids to pureed foods. After that, you can eat soft foods, then move on to firmer foods as your body is able to tolerate them. For the next 3 weeks a protein-enriched diet and daily multi-vitamins, oral supplements (calcium, iron and fat-soluble vitamins – A,D,E,K) are recommended 59. The gallstone prophylaxis is initiated in the patients with intact gallbladders (500 mg/day of Ursodeoxicolicacid). A CT-scan will be considered at any time a complication is suspected.

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) recommends that healthcare providers prescribe these daily supplements after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch weight-loss surgery to help prevent nutritional deficiencies:

- Vitamin A, starting 2 to 4 weeks after surgery

- Vitamin D, starting 2 to 4 weeks after surgery

- Vitamin K, starting 2 to 4 weeks after surgery

- Multivitamin with 200% of the daily values, starting the first day after discharge from the hospital

- Minimum of 18 mg to 27 mg of iron, and up to 50 mg to 100 mg a day for menstruating women or adolescents at risk for anemia

- Calcium supplements, usually taken as 3 to 4 doses of 500 mg to 600 mg doses, starting on the first day after your discharge or within the first month after surgery. Note: Don’t take these at the same time as iron supplements. Wait a couple of hours.

- Vitamin B12 supplements containing 350 mcg to 500 mcg. Some people will need to give themselves B12 injections every month

- Optional B-complex vitamin

- Up to 3 servings of calcium-rich dairy beverages

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) also recommends that you eat small but nutritious meals that are high in protein, along with fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and omega-3 fatty acids. You should avoid meals high in sugar.

Your doctor will probably recommend that you work with a dietitian to plan healthy meals that give you enough protein, vitamins, and minerals while you are losing weight. Even with a healthy diet, you probably will need to take vitamin and mineral supplements for the rest of your life.

It’s important to understand that following a healthy lifestyle is critical to maintaining weight loss after surgery. This includes eating a healthy diet and getting plenty of regular exercise. And it requires a lifelong commitment, with regular visits to your bariatric surgeon or other healthcare provider for periodic lab checks. The duodenal switch can result in considerable weight loss. It also offers improvement or resolution of many obesity-related medical conditions. But it needs regular follow-up and a commitment to taking the protein, vitamins, and supplements that you will need.

But if you continue to drink a lot of high-calorie liquid such as soda or fruit juice, you may not lose weight. If you continually overeat, your stomach may stretch. If your stomach stretches, you will not benefit from your surgery.

What are the alternatives to biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch?

The alternatives to biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch surgery are lifestyle changes, such as diet and exercise, or lifestyle changes combined with weight-loss medicines or lap band surgery (adjustable gastric banding) or gastric sleeve surgery or gastric bypass surgery. You can get professional help with this: ask your doctor.

A prospective, cross-sectional study 60 assessed weight loss, food tolerance and diet quality in 130 subjects (14 obese pre-surgical controls, 13 adjustable gastric banding, 62 gastric sleeve and 41 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) found the obese pre-surgical controls and adjustable gastric banding groups consumed significantly more high-calorie extra foods, resulting in poor weight loss and food tolerance outcomes for the adjustable gastric banding group. The control and adjustable gastric banding groups consumed significantly more high-calorie extra foods (9.2 and 7.7 daily serves respectively) compared with the gastric sleeve (3.4 serves) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (4.0 serves) groups. There were several significant correlations between food tolerance and dietary intake including breads and cereals and meat and meat alternatives.

Which type of weight loss surgery is right for me?

Many factors will determine which type of weight loss surgery is the best type for you, including how much weight you need to lose and any illnesses you might have.

Your doctor will do a detailed assessment and discuss with you the best option, including the risks.

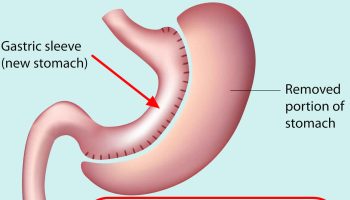

Gastric sleeve

Gastric sleeve surgery, also called “vertical sleeve gastrectomy” (VSG) or “sleeve gastrectomy“, is a newer type of weight loss surgery (bariatric surgery) where a surgeon removes most of your stomach (removing approximately 80 to 85% of the greater curvature of stomach) and makes a narrow tube or “gastric sleeve” out of the remaining stomach, leaving only a banana-shaped section that is closed with staples (Figure 7) 61, 62, 63, 64. Your new, banana-shaped stomach is much smaller than your original stomach. After the gastric sleeve surgery, your stomach will hold only about a tenth of what it did before, making you feel full sooner after eating a small amount of food and be less hungry. You might also feel less hungry because your smaller stomach will produce lower levels of a hormone called ghrelin, which causes hunger and you may lose from 50 to 90 pounds. Taking out part of your stomach may also affect other hormones and bacteria in your gastrointestinal system that affect appetite and metabolism. Gastric sleeve surgery cannot be reversed because some of your stomach is permanently removed. Endoscopic gastric sleeve surgery is less invasive and cheaper than other forms of bariatric surgery.

Gastric sleeve surgery is done as a laparoscopic surgery, with small incisions in the upper abdomen. Most of the left part of the stomach is removed. The remaining stomach is then a narrow tube called a sleeve. Food empties out of the bottom of the stomach into the small intestine the same way that it did before surgery. The small intestine is not operated on or changed. After the surgery, less food will make you full when eating.

Like other weight-loss procedures, endoscopic gastric sleeve surgery requires commitment to a healthier lifestyle. Gastric sleeve surgery isn’t a “fix it and forget it” kind of surgery. To be considered for gastric sleeve surgery, a person must be committed to changing his or her eating and exercise habits over the long term to help ensure the long-term success of endoscopic gastric sleeve surgery. Not everyone who wants the gastric sleeve surgery will be eligible to get it.

Gastric sleeve surgery is typically done only after you’ve tried to lose weight by improving your diet and exercise habits.

Doctors consider a number of things when deciding if weight loss surgery is the right choice for you. These include whether you are:

- at least 14 years old and near adult height with more than 100 pounds of extra weight to lose

- healthy enough to handle surgery

- have medical problems that could improve with significant weight loss, such as sleep apnea, diabetes, or heart problems

- have proved that you can stick to a healthy diet and get regular exercise

- have family members who will provide emotional and practical support (like driving to every doctor’s visit or buying healthy food)

In general, gastric sleeve surgery could be an option for you if 22, 23, 24, 25:

- Your body mass index (BMI) is 40 kg/m² or higher (extreme obesity).

- Your BMI is 35 to 39.9 kg/m² (obesity), and you have a serious weight-related health problem, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure or severe obstructive sleep apnea. In some cases, you may qualify for certain types of weight-loss surgery if your BMI is 30 to 34 kg/m² and you have serious weight-related health problems.

You must also be willing to make permanent changes to lead a healthier lifestyle. You may be required to participate in long-term follow-up plans that include monitoring your nutrition, your lifestyle and behavior, and your medical conditions.

Check with your health insurance plan or your regional Medicare or Medicaid office to find out if your policy covers weight-loss surgery.

Endoscopic gastric sleeve surgery can lead to significant weight loss. The amount of weight you lose also depends on how much you can change your lifestyle habits.

But studies have shown promising results. A recent study of people with an average body mass index (BMI) around 38 kg/m² found that endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty led to an average weight loss of 39 pounds (17.8 kilograms) after 6 months. After 12 months, weight loss was 42 pounds (19 kilograms).

In a study of people with an average body mass index (BMI) of about 45 kg/m², the procedure resulted in an average weight loss of about 73 pounds (33 kilograms) during the first six months.

As with other weight loss procedures and surgeries that lead to significant weight loss, endoscopic gastric sleeve surgery may improve conditions often related to being overweight, including:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Heart disease

- Stroke

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Type 2 diabetes

- Stroke

- Cancer

- Infertility

Figure 7. Gastric sleeve surgery

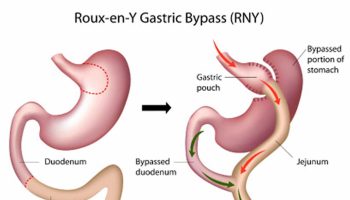

Gastric bypass surgery

A gastric bypass surgery or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a type of weight-loss surgery (bariatric surgery) where surgical staples are used to create a small pouch at the top of the stomach. This pouch will hold about 1 cup of food. The pouch is then connected to your small intestine, bypassing (missing out) the rest of the stomach. This means it takes less food to make you feel full and you’ll absorb fewer calories from the food you eat. Gastric bypass surgery is one of the most common types of weight loss surgery in the United States. Gastric bypass surgery is done when lifestyle intervention (diet and physical activity) and drugs haven’t worked or when you have serious health problems because of your weight.

In Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, the rest of your stomach will still be there, but food won’t go to it. The pouch is the only part of the stomach that receives food. This greatly limits the amount that you can comfortably eat and drink at one time.

Next, the small intestine is then cut a short distance below the main stomach and connected to the new pouch. Your surgeon will attach one end of it to the small stomach pouch and the other end lower down on the small intestine, making a “Y” shape. That’s the bypass part of the procedure. The rest of your stomach is still there. It delivers chemicals from the pancreas to help digest food that comes from the small pouch. Doctors use the laparoscopic method for most gastric bypasses.

Food flows directly from the pouch into this part of the intestine. The main part of the stomach, however, continues to make digestive juices. The portion of the intestine still attached to the main stomach is reattached farther down. This allows the digestive juices to flow to the small intestine. Because food now bypasses a portion of the small intestine, fewer nutrients and calories are absorbed.

Gastric bypass surgery can provide long-term weight loss. The amount of weight you lose depends on your type of surgery and your change in lifestyle habits. It may be possible to lose 60 percent, or even more, of your excess weight within two years.

In addition to weight loss, gastric bypass surgery may improve or resolve conditions often related to being overweight, including:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Type 2 diabetes

- Stroke

- Infertility

Gastric bypass surgery can also improve your ability to perform routine daily activities, which could help improve your quality of life.

Figure 8. Gastric bypass before and after

Footnote: Before gastric bypass, food (see arrows) enters your stomach and passes into the small intestine. After surgery, the amount of food you can eat is reduced due to the smaller stomach pouch. Food is also redirected so that it bypasses most of your stomach and the first section of your small intestine (duodenum). Food flows directly into the middle section of your small intestine (jejunum), altering the secretion of gastrointestinal hormones and thereby affecting your appetite and metabolism.

Figure 9. Gastric bypass surgery or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or Lap Band

In laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, a hollow, flexible silicone band is placed around the upper stomach, which causes a restrictive effect, reduces stomach capacity, and produces rapid feelings of satiety. The band is tightened by injecting saline into it through a subcutaneous port, which is located just inferior to the sternum or lateral to the umbilicus (Figure 10). Because of a higher complication rate and less weight loss compared with the other two most common procedures (gastric sleeve and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass), the demand for gastric banding is decreasing in the United States 65.

Figure 10. Adjustable Gastric Banding

References- Harris LA, Kayser BD, Cefalo C, Marini L, Watrous JD, Ding J, Jain M, McDonald JG, Thompson BM, Fabbrini E, Eagon JC, Patterson BW, Mittendorfer B, Mingrone G, Klein S. Biliopancreatic Diversion Induces Greater Metabolic Improvement Than Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Cell Metab. 2019 Nov 5;30(5):855-864.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.09.002

- Bariatric Surgery Procedures. https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures

- Topart P, Becouarn G, Delarue J. Weight Loss and Nutritional Outcomes 10 Years after Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch. Obes Surg. 2017 Jul;27(7):1645-1650. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2537-x

- Sethi M, Chau E, Youn A, Jiang Y, Fielding G, Ren-Fielding C. Long-term outcomes after biliopancreatic diversion with and without duodenal switch: 2-, 5-, and 10-year data. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016 Nov;12(9):1697-1705. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.006

- Rubino F, Schauer PR, Kaplan LM, Cummings DE. Metabolic surgery to treat type 2 diabetes: clinical outcomes and mechanisms of action. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:393-411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.051308.105148

- Ren CJ, Patterson E, Gagner M. Early results of laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch: a case series of 40 consecutive patients. Obes Surg. 2000 Dec;10(6):514-23; discussion 524. doi: 10.1381/096089200321593715

- de Csepel J, Burpee S, Jossart G, Andrei V, Murakami Y, Benavides S, Gagner M. Laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch for morbid obesity: a feasibility study in pigs. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001 Apr;11(2):79-83. doi: 10.1089/109264201750162293

- Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, Mavandadi S, Zainabadi K, Wilson SE. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg. 2004 Oct;240(4):586-93; discussion 593-4. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000140752.74893.24

- Ballantyne GH, Belsley S, Stephens D, Saunders JK, Trivedi A, Ewing DR, Iannace V, Davis D, Capella RF, Wasielewski A, Moran S, Schmidt HJ. Bariatric surgery: low mortality at a high-volume center. Obes Surg. 2008 Jun;18(6):660-7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9357-y

- Biertho L, Lebel S, Marceau S, Hould FS, Lescelleur O, Moustarah F, Simard S, Biron S, Marceau P. Perioperative complications in a consecutive series of 1000 duodenal switches. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013 Jan-Feb;9(1):63-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.10.021

- Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Sledge I. Trends in mortality in bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2007 Oct;142(4):621-32; discussion 632-5. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.018

- Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013 Apr;23(4):427-36. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0864-0

- Ponce J, DeMaria EJ, Nguyen NT, Hutter M, Sudan R, Morton JM. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of bariatric surgery procedures in 2015 and surgeon workforce in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016 Nov;12(9):1637-1639. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.488

- Gadde KM, Martin CK, Berthoud HR, Heymsfield SB. Obesity: Pathophysiology and Management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 2;71(1):69-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.011

- Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2020. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers

- Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, Schindler K, Busetto L, Micic D, Toplak H; Obesity Management Task Force of the European Association for the Study of Obesity. European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. Obes Facts. 2015;8(6):402-24. doi: 10.1159/000442721. Epub 2015 Dec 5. Erratum in: Obes Facts. 2016;9(1):64.

- Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, Bantle JP, Sledge I. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009 Mar;122(3):248-256.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041

- Søvik TT, Aasheim ET, Taha O, Engström M, Fagerland MW, Björkman S, Kristinsson J, Birkeland KI, Mala T, Olbers T. Weight loss, cardiovascular risk factors, and quality of life after gastric bypass and duodenal switch: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Sep 6;155(5):281-91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-5-201109060-00005

- Prachand VN, Davee RT, Alverdy JC. Duodenal switch provides superior weight loss in the super-obese (BMI > or =50 kg/m2) compared with gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2006 Oct;244(4):611-9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000239086.30518.2a

- Ward M, Prachand V. Surgical treatment of obesity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 Nov;70(5):985-90. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.001

- Skogar ML, Sundbom M. Duodenal Switch Is Superior to Gastric Bypass in Patients with Super Obesity when Evaluated with the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS). Obes Surg. 2017 Sep;27(9):2308-2316. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2680-z

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S102-38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. Epub 2013 Nov 12. Erratum in: Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129(25 Suppl 2):S139-40.

- Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity consensus statement. Nutrition Today 1991;26:32–35.

- Harith Rajagopalan, Alan D. Cherrington, Christopher C. Thompson, Lee M. Kaplan, Francesco Rubino, Geltrude Mingrone, Pablo Becerra, Patricia Rodriguez, Paulina Vignolo, Jay Caplan, Leonardo Rodriguez, Manoel P. Galvao Neto; Endoscopic Duodenal Mucosal Resurfacing for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: 6-Month Interim Analysis From the First-in-Human Proof-of-Concept Study. Diabetes Care 1 December 2016; 39 (12): 2254–2261. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-0383

- Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL, Farooqi IS, Murad MH, Silverstein JH, Yanovski JA. Pediatric Obesity-Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Mar 1;102(3):709-757. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2573

- Himpens J. Is duodenal switch the preferred option after failed Roux-en-Y gastric bypass? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016 Nov;12(9):1678-1680. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.04.010

- Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: A joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861–877. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0236

- McTigue KM, Wellman R, Nauman E, et al. Comparing the 5-year diabetes outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet) Bariatric Study. JAMA Surgery. 2020;e200087. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0087

- O’Kane M, Parretti HM, Pinkney J, Welbourn R, Hughes CA, Mok J, Walker N, Thomas D, Devin J, Coulman KD, Pinnock G, Batterham RL, Mahawar KK, Sharma M, Blakemore AI, McMillan I, Barth JH. British Obesity and Metabolic Surgery Society Guidelines on perioperative and postoperative biochemical monitoring and micronutrient replacement for patients undergoing bariatric surgery-2020 update. Obes Rev. 2020 Nov;21(11):e13087. doi: 10.1111/obr.13087

- Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, Craggs-Dino L, Isom KA, Greiman L. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 May;13(5):727-741. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018

- Edholm D, Kullberg J, Haenni A, Karlsson FA, Ahlström A, Hedberg J, Ahlström H, Sundbom M. Preoperative 4-week low-calorie diet reduces liver volume and intrahepatic fat, and facilitates laparoscopic gastric bypass in morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2011 Mar;21(3):345-50. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0337-2

- Baldry EL, Leeder PC, Idris IR. Pre-operative dietary restriction for patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the UK: observational study of current practice and dietary effects. Obes Surg. 2014 Mar;24(3):416-21. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1125-6

- Farrell, M. (2017). Smeltzer & Bare’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- How does the stomach work ? National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072488/

- Choban PS, Jackson B, Poplawski S, Bistolarides P. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: why, who, when, how, where, and then what? Cleve Clin J Med. 2002 Nov;69(11):897-903. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.69.11.897

- Tewksbury C, Williams NN, Dumon KR, Sarwer DB. Preoperative Medical Weight Management in Bariatric Surgery: a Review and Reconsideration. Obes Surg. 2017 Jan;27(1):208-214. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2422-7

- Anderson B, Gill RS, de Gara CJ, Karmali S, Gagner M. Biliopancreatic diversion: the effectiveness of duodenal switch and its limitations. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:974762. doi: 10.1155/2013/974762

- Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium; Flum DR, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, Pories W, Courcoulas A, McCloskey C, Mitchell J, Patterson E, Pomp A, Staten MA, Yanovski SZ, Thirlby R, Wolfe B. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jul 30;361(5):445-54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901836

- Demaria EJ, Winegar DA, Pate VW, Hutcher NE, Ponce J, Pories WJ. Early postoperative outcomes of metabolic surgery to treat diabetes from sites participating in the ASMBS bariatric surgery center of excellence program as reported in the Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database. Ann Surg. 2010 Sep;252(3):559-66; discussion 566-7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f2aed0

- Hamoui N, Chock B, Anthone GJ, Crookes PF. Revision of the duodenal switch: indications, technique, and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 Apr;204(4):603-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.011

- T T Søvik, O Taha, E T Aasheim, M Engström, J Kristinsson, S Björkman, C F Schou, H Lönroth, T Mala, T Olbers, Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity, British Journal of Surgery, Volume 97, Issue 2, February 2010, Pages 160–166, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6802

- Chang SH, Freeman NLB, Lee JA, Stoll CRT, Calhoun AJ, Eagon JC, Colditz GA. Early major complications after bariatric surgery in the USA, 2003-2014: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2018 Apr;19(4):529-537. doi: 10.1111/obr.12647

- Anthone GJ, Lord RV, DeMeester TR, Crookes PF. The duodenal switch operation for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2003 Oct;238(4):618-27; discussion 627-8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000090941.61296.8f

- Jacobsen HJ, Nergard BJ, Leifsson BG, Frederiksen SG, Agajahni E, Ekelund M, Hedenbro J, Gislason H. Management of suspected anastomotic leak after bariatric laparoscopic Roux-en-y gastric bypass. Br J Surg. 2014 Mar;101(4):417-23. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9388

- Ma IT, Madura JA 2nd. Gastrointestinal Complications After Bariatric Surgery. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015 Aug;11(8):526-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4843041

- Conner J, Nottingham JM. Biliopancreatic Diversion With Duodenal Switch. [Updated 2022 Sep 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563193

- Faintuch J, Matsuda M, Cruz ME, Silva MM, Teivelis MP, Garrido AB Jr, Gama-Rodrigues JJ. Severe protein-calorie malnutrition after bariatric procedures. Obes Surg. 2004 Feb;14(2):175-81. doi: 10.1381/096089204322857528

- Marceau P, Biron S, Lebel S, Marceau S, Hould FS, Simard S, Dumont M, Fitzpatrick LA. Does bone change after biliopancreatic diversion? J Gastrointest Surg. 2002 Sep-Oct;6(5):690-8. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)00086-5

- Marceau P, Biron S, Hould FS, Lebel S, Marceau S, Lescelleur O, Biertho L, Simard S. Duodenal switch: long-term results. Obes Surg. 2007 Nov;17(11):1421-30. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9435-9

- Aasheim ET, Björkman S, Søvik TT, Engström M, Hanvold SE, Mala T, Olbers T, Bøhmer T. Vitamin status after bariatric surgery: a randomized study of gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jul;90(1):15-22. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27583. Epub 2009 May 13. Erratum in: Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Jan;91(1):239-40.

- Sinha N, Shieh A, Stein EM, Strain G, Schulman A, Pomp A, Gagner M, Dakin G, Christos P, Bockman RS. Increased PTH and 1.25(OH)(2)D levels associated with increased markers of bone turnover following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011 Dec;19(12):2388-93. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.133

- Slater GH, Ren CJ, Siegel N, Williams T, Barr D, Wolfe B, Dolan K, Fielding GA. Serum fat-soluble vitamin deficiency and abnormal calcium metabolism after malabsorptive bariatric surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004 Jan;8(1):48-55; discussion 54-5. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.09.020

- Balsa JA, Botella-Carretero JI, Peromingo R, Caballero C, Muñoz-Malo T, Villafruela JJ, Arrieta F, Zamarrón I, Vázquez C. Chronic increase of bone turnover markers after biliopancreatic diversion is related to secondary hyperparathyroidism and weight loss. Relation with bone mineral density. Obes Surg. 2010 Apr;20(4):468-73. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0028-z

- Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, Cooper A, van Staa TP, Cooper C, Harvey NC. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012 Aug 3;345:e5085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5085

- Stroh C, Weiher C, Hohmann U, Meyer F, Lippert H, Manger T. Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) after a duodenal switch procedure: a case report. Obes Surg. 2010 Mar;20(3):397-400. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9913-8

- Aasheim ET, Søvik TT, Bakke EF. Night blindness after duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008 Sep-Oct;4(5):685-6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.05.001

- Aasheim ET. Wernicke encephalopathy after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2008 Nov;248(5):714-20. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181884308

- Primavera A, Brusa G, Novello P, Schenone A, Gianetta E, Marinari G, Cuneo S, Scopinaro N. Wernicke-Korsakoff Encephalopathy Following Biliopancreatic Diversion. Obes Surg. 1993 May;3(2):175-177. doi: 10.1381/096089293765559548

- Copăescu C. Laparoscopic Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch – The Most Effective Operation for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. How I do it? Chirurgia (Bucur). 2018 Sept-Oct;113(5):704-711. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.113.5.704

- Food tolerance and diet quality following adjustable gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014 Mar-Apr;8(2):e115-200. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2013.02.002. https://www.obesityresearchclinicalpractice.com/article/S1871-403X(13)00014-8/fulltext

- Sleeve gastrectomy. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/sleeve-gastrectomy/about/pac-20385183

- Types of Weight-loss Surgery. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/bariatric-surgery/types

- Brethauer SA. Sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2011 Dec;91(6):1265-79, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.08.012

- Gumbs AA, Gagner M, Dakin G, Pomp A. Sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2007 Jul;17(7):962-9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9151-x

- Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):275-287.