What is bladder cancer

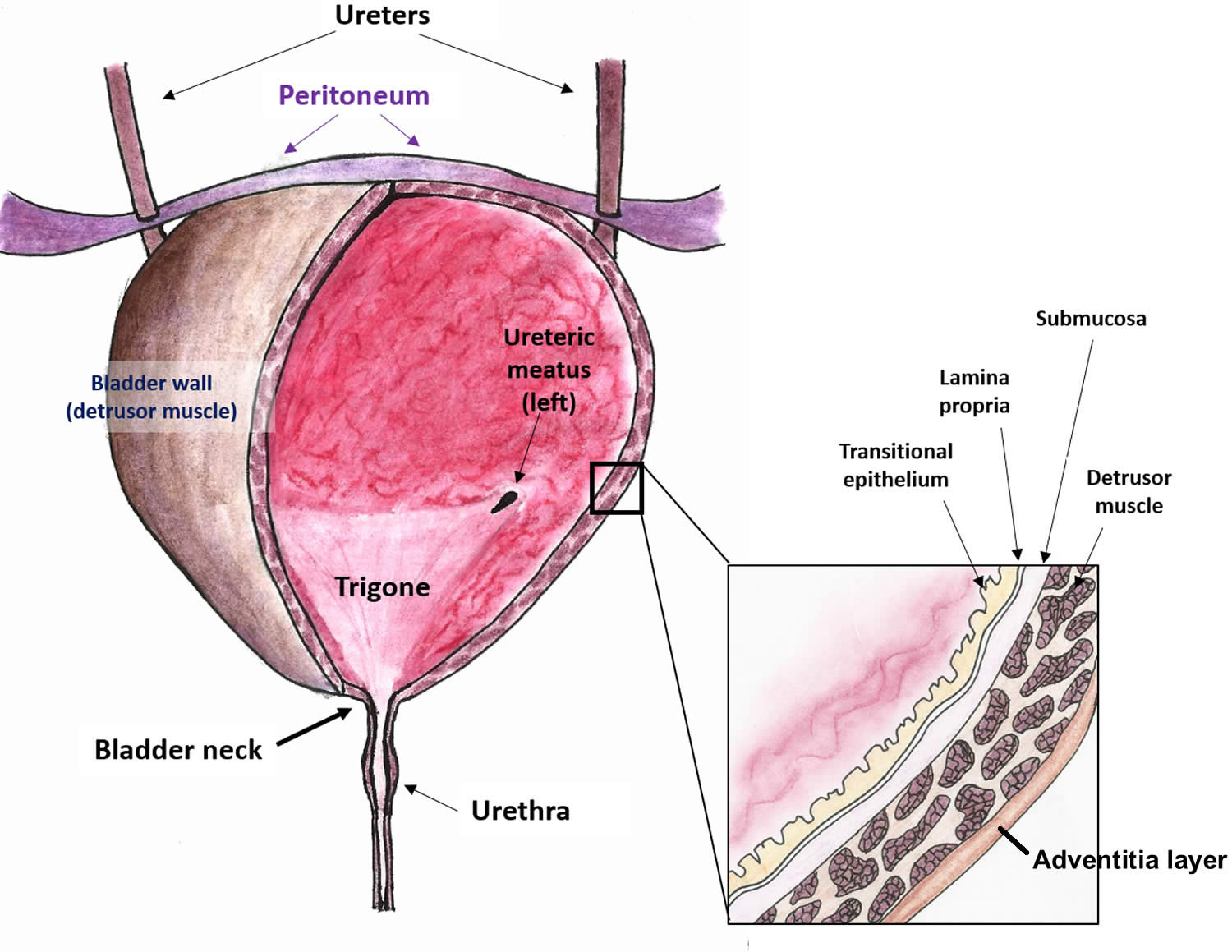

Bladder cancer begins when cells in the urinary bladder start to grow uncontrollably. As more cancer cells develop, they can form a tumor and spread to other areas of the body. The bladder is part of the urinary system, your bladder is like a balloon which stores urine. It’s a stretchy bag made of muscle tissue. The bladder can hold about 300 to 400 mls of urine. The wall of the bladder has several layers, which are made up of different types of cells. Most bladder cancers start in the innermost lining of the bladder, which is called the urothelium or transitional epithelium (see Figure 5 below). Although it’s most common in the bladder, this same type of cancer can occur in other parts of the urinary tract drainage system. As the cancer grows into or through the other layers in the bladder wall, it becomes more advanced and can be harder to treat.

Over time, the cancer might grow outside the bladder and into nearby structures. It might spread to nearby lymph nodes, or to other parts of the body. If bladder cancer spreads, it often goes first to distant lymph nodes, the bones, the lungs, or the liver.

Bladder cancer represents 4.2% of all new cancer cases in the U.S. Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in men, but it’s less common in women. This may be because more men than women have smoked or been exposed to chemicals at work in recent decades.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for bladder cancer in the United States for 2022 are 1, 2:

- New cases: About 81,180 new cases of bladder cancer (about 61,700 in men and 19,480 in women).

- Deaths: About 17,100 deaths from bladder cancer (about 12,120 in men and 4,980 in women).

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 77.1%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 2.8%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of bladder cancer was 18.7 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 4.2 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 2.3 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with bladder cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 712,644 people living with bladder cancer in the United States.

- Bladder cancer occurs mainly in older people. About 9 out of 10 people with this cancer are over the age of 55. The average age of people when they are diagnosed is 73. Overall, the chance men will develop this cancer during their life is about 1 in 27. For women, the chance is about 1 in 89. But each person’s chances of getting bladder cancer can be affected by certain risk factors.

- Whites are more likely to be diagnosed with bladder cancer than African Americans or Hispanic Americans.

The rates of new bladder cancers and deaths linked to bladder cancer and have been dropping slightly in women in recent years. In men, incidence rates have been decreasing, but death rates have been stable.

About half of all bladder cancers are first found while the cancer is still found only in the inner layer of the bladder wall. These are non-invasive or in situ cancers. About 1 in 3 bladder cancers have spread into deeper layers but are still only in the bladder. In most of the remaining cases, the cancer has spread to nearby tissues or lymph nodes outside the bladder. Rarely (in about 4% of cases), it has spread to distant parts of the body. Black patients are slightly more likely to have more advanced disease when they’re diagnosed, compared to whites.

The treatment options for bladder cancer largely depend on how far the cancer has grown into the layers of your bladder also known as the stage of your cancer.

Treatments usually differ between early stage, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer and more advanced muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Bladder cancer treatment may include:

- Surgery, to remove the cancer cells

- Chemotherapy in the bladder (intravesical chemotherapy), to treat cancers that are confined to the lining of the bladder but have a high risk of recurrence or progression to a higher stage

- Chemotherapy for the whole body (systemic chemotherapy), to increase the chance for a cure in a person having surgery to remove the bladder, or as a primary treatment when surgery isn’t an option

- Radiation therapy, to destroy cancer cells, often as a primary treatment when surgery isn’t an option or isn’t desired

- Immunotherapy, to trigger the body’s immune system to fight cancer cells, either in the bladder or throughout the body

- Targeted therapy, to treat advanced cancer when other treatments haven’t helped

A combination of treatment approaches may be recommended by your doctor and members of your care team.

Figure 1. Urinary bladder location

Figure 2. Urinary bladder anatomy

Figure 3. Bladder cancer

Figure 4. Bladder cancer type

Layers of the bladder

Your bladder is made up of layers.

- The first layer is on the inside of your bladder and is called transitional epithelium. It is a special type of lining that stretches as the bladder fills up. It stops the urine being absorbed back into your body.

- The second layer is a thin layer of connective tissue called the lamina propria.

- The third layer is muscle tissue called the muscularis propria.

- The fourth layer is fatty connective tissue. It separates the bladder from other body organs, such as the prostate and kidneys.

Figure 5. Layers of the bladder

Types of bladder cancer

There are different types of bladder cancer. The type of bladder cancer means the type of cell the cancer started in. Knowing this helps your doctor decide which treatment you need.

The most common type of bladder cancer is transitional cell bladder cancer (TCC) also called urothelial bladder cancer or urothelial carcinoma.

Rarer types include squamous cell bladder cancer, adenocarcinoma, sarcoma and small cell bladder cancer.

Doctors also describe your bladder cancer based on how far it has spread into the bladder wall. You can have either non muscle invasive (early or superficial) bladder cancer or invasive bladder cancer.

Urothelial carcinoma (transitional cell carcinoma)

Urothelial carcinoma also known as transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), is by far the most common type of bladder cancer 3. In fact, if you are told you have bladder cancer it is almost certain to be a urothelial carcinoma. These cancers start in the urothelial cells that line the inside of the bladder.

Urothelial cells also line other parts of the urinary tract, such as the part of the kidney that connects to the ureter (called the renal pelvis), the ureters, and the urethra. People with bladder cancer sometimes have tumors in these places, too, so all of the urinary tract needs to be checked for tumors.

Squamous cell carcinoma

In the US, only about 1% to 2% of bladder cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. Seen with a microscope, the cells look much like the flat cells that are found on the surface of the skin. Nearly all squamous cell carcinomas of the bladder are invasive.

Adenocarcinoma

Only about 1% of bladder cancers are adenocarcinomas. These cancer cells have a lot in common with gland-forming cells of colon cancers. Nearly all adenocarcinomas of the bladder are invasive.

Small cell carcinoma

Less than 1% of bladder cancers are small-cell carcinomas. They start in nerve-like cells called neuroendocrine cells. These cancers often grow quickly and usually need to be treated with chemotherapy like that used for small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Sarcoma

Sarcomas start in the muscle cells of the bladder, but they are rare. These less common types of bladder cancer (other than sarcoma) are treated similar to transitional cell carcinomas, especially for early stage tumors, but if chemotherapy is needed, different drugs might be used.

Invasive versus non-invasive bladder cancer

The wall of the bladder has many several layers. Each layer is made up of different kinds of cells (see Figure 5). Most bladder cancers start in the innermost lining of the bladder, which is called the urothelium or transitional epithelium. As the cancer grows into or through the other layers in the bladder wall, it has a higher stage, becomes more advanced, and can be harder to treat.

Over time, the cancer might grow outside the bladder and into nearby structures. It might spread to nearby lymph nodes, or to other parts of the body. When bladder cancer spreads, it tends to go to distant lymph nodes, the bones, the lungs, or the liver.

Bladder cancers are often described based on how far they have invaded into the wall of the bladder:

- Non-invasive cancers are still in the inner layer of cells (the transitional epithelium) but have not grown into the deeper layers.

- Invasive cancers have grown into deeper layers of the bladder wall. These cancers are more likely to spread and are harder to treat.

A bladder cancer can also be described as superficial or non-muscle invasive. These terms include both non-invasive tumors as well as any invasive tumors that have not grown into the main muscle layer of the bladder.

- About half of all bladder cancers are first found while the cancer is still confined to the inner layer of the bladder wall. These are called non-invasive or in situ cancers.

- About 1 in 3 bladder cancers have invaded into deeper layers but are still only in the bladder.

- In most of the remaining cases, the cancer has spread to nearby tissues or lymph nodes outside the bladder.

- Rarely (in about 4% of cases), it has spread to distant parts of the body. Black patients are slightly more likely to have more advanced disease when they are diagnosed, compared to whites.

Papillary versus flat cancer

Bladder cancers are also divided into 2 subtypes, papillary and flat, based on how they grow (see Figure 4).

- Papillary carcinomas grow in slender, finger-like projections from the inner surface of the bladder toward the hollow center. Papillary tumors often grow toward the center of the bladder without growing into the deeper bladder layers. These tumors are called non-invasive papillary cancers. Very low-grade (slow growing), non-invasive papillary cancer is sometimes called papillary urothelial neoplasm of low-malignant potential and tends to have a very good outcome.

- Flat carcinomas do not grow toward the hollow part of the bladder at all. If a flat tumor is only in the inner layer of bladder cells, it is known as a non-invasive flat carcinoma or a flat carcinoma in situ (CIS).

If either a papillary or flat tumor grows into deeper layers of the bladder, it is called an invasive urothelial (or transitional cell) carcinoma.

Bladder cancer signs and symptoms

The main symptom of bladder cancer is blood in your urine also called hematuria. 8 out of 10 people with bladder cancer (80%) have some blood in their urine. This is the same for both men and women. Blood in urine (hematuria) may cause urine to appear bright red or cola colored, though sometimes the urine appears normal and blood is detected on a lab test

Other signs and symptoms of bladder cancer may include:

- Frequent urination

- Passing urine very suddenly (urgency)

- Pain or a burning sensation when passing urine

- Weight loss

- Pain in your back, lower tummy or bones

- Feeling tired and unwell

If you notice that you have discolored urine and are concerned it may contain blood, make an appointment with your doctor to get it checked. Also make an appointment with your doctor if you have other signs or symptoms that worry you.

These symptoms are much more likely to be caused by other conditions rather than cancer. For example a urine infection, particularly if you do not have blood in your urine. For men, the symptoms could be caused by an enlarged prostate gland.

But do tell your doctor straight away if you have these symptoms. If you have an infection, it can usually be cleared up very quickly with antibiotics. And it is always best to check for cancer as early as possible so that it can be diagnosed while it is easier to treat.

Blood in the urine

In most cases, blood in the urine (hematuria) is the first sign of bladder cancer. There may be enough blood to change the color of the urine to orange, pink, or, less often, dark red. Sometimes, the color of the urine is normal but small amounts of blood are found when a urine test (urinalysis) is done because of other symptoms or as part of a general medical check-up.

Blood may be present one day and absent the next, with the urine remaining clear for weeks or even months. But if a person has bladder cancer, at some point the blood reappears.

Usually, the early stages of bladder cancer (when it’s small and only in the bladder) cause bleeding but little or no pain or other symptoms.

Blood in the urine doesn’t always mean you have bladder cancer. More often it’s caused by other things like an infection, benign (not cancer) tumors, stones in the kidney or bladder, or other benign kidney diseases. Still, it’s important to have it checked by a doctor so the cause can be found.

Changes in bladder habits or symptoms of irritation

Bladder cancer can sometimes cause changes in urination, such as:

- Having to urinate more often than usual

- Pain or burning during urination

- Feeling as if you need to go right away, even when your bladder isn’t full

- Having trouble urinating or having a weak urine stream

- Having to get up to urinate many times during the night

These symptoms are also more likely to be caused by a urinary tract infection (UTI), bladder stones, an overactive bladder, or an enlarged prostate (in men). Still, it’s important to have them checked by a doctor so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Symptoms of advanced bladder cancer

Bladder cancers that have grown large enough or have spread to other parts of the body can sometimes cause other symptoms, such as:

- Being unable to urinate

- Lower back pain on one side

- Loss of appetite and weight loss

- Feeling tired or weak

- Swelling in the feet

- Bone pain

Again, many of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by something other than bladder cancer, but it’s important to have them checked so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

If there is a reason to suspect you might have bladder cancer, the doctor will use one or more exams or tests to find out if it is cancer or something else.

Bladder cancer complications

Complications of bladder cancer include symptoms related to the tumor and treatment of adverse effects. Complications related to the tumor include weight loss, fatigue, urinary tract infection (UTI), metastasis, and urinary obstruction leading to chronic kidney failure 4. The adverse effects of surgical management include urinary tract infection (UTI), urinary leak, pouch stones, urinary tract obstruction, erectile dysfunction, and vaginal narrowing 5.

Bladder cancer causes

Researchers do not know exactly what causes most bladder cancers. But they have found some risk factors and are starting to understand how they cause cells in the bladder to become cancer.

Most cases of bladder cancer appear to be caused by exposure to harmful substances, which lead to abnormal changes in the bladder’s cells over many years.

Tobacco smoke is a common cause and it’s estimated that more than 1 in 3 cases of bladder cancer are caused by smoking.

Contact with certain chemicals previously used in manufacturing is also known to cause bladder cancer. However, these substances have since been banned.

Certain changes in the DNA inside normal bladder cells can make them grow abnormally and form cancers. DNA is the chemical in each of your cells that makes up your genes, which control how your cells function. You usually look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA, but DNA affects more than just how you look.

Some genes control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die:

- Genes that help cells grow, divide, and stay alive are called oncogenes.

- Genes that normally help control cell division, repair mistakes in DNA, or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA changes (gene mutations) that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes. Several different gene changes are usually needed for a cell to become cancer.

Acquired gene mutations

Most gene mutations related to bladder cancer develop during a person’s life rather than having been inherited before birth. Some of these acquired gene mutations result from exposure to cancer-causing chemicals or radiation. For example, chemicals in tobacco smoke can be absorbed into the blood, filtered by the kidneys, and end up in urine, where they can affect bladder cells. Other chemicals may reach the bladder the same way. But sometimes, gene changes may just be random events that sometimes happen inside a cell, without having an outside cause.

The gene changes that lead to bladder cancer are not the same in all people. Acquired changes in certain genes, such as the TP53 or RB1 tumor suppressor genes and the FGFR and RAS oncogenes, are thought to be important in the development of some bladder cancers. Changes in these and similar genes may also make some bladder cancers more likely to grow and spread into the bladder wall than others. Research in this field is aimed at developing tests that can find bladder cancers at an early stage by finding their DNA changes.

Inherited gene mutations

Some people inherit gene changes from their parents that increase their risk of bladder cancer. But bladder cancer does not often run in families, and inherited gene mutations are not thought to be a major cause of this disease.

Some people seem to inherit a reduced ability to detoxify (break down) and get rid of certain types of cancer-causing chemicals. These people are more sensitive to the cancer-causing effects of tobacco smoke and certain industrial chemicals. Researchers have developed tests to identify such people, but these tests are not routinely done. It’s not certain how helpful the results of such tests might be, since doctors already recommend that all people avoid tobacco smoke and hazardous industrial chemicals.

Bladder cancer risk factors

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. But having a risk factor, or even many, does not mean that you will get the disease. Many people with risk factors never get bladder cancer, while others with this disease may have few or no known risk factors.

Still, it’s important to know about the risk factors for bladder cancer because there may be things you can do that might lower your risk of getting it. If you’re at higher risk because of certain factors, you might be helped by tests that could find it early, when treatment is most likely to be effective.

Many risk factors make a person more likely to develop bladder cancer.

Risk factors you can change

Smoking

Smoking cigarettes is the most important risk factor for bladder cancer. Smokers are up to 4 times as likely to get bladder cancer as nonsmokers. Smoking causes about half of all bladder cancers in both men and women.

People with the highest risk are those who:

- smoke heavily

- started smoking at a young age

- have smoked for a long time

Smoking other types of tobacco products like cigars and pipes also increases your risk.

How smoking may increase your risk

- Chemicals in the smoke get into the bloodstream. They are then filtered out of the blood by the kidneys and end up in the urine. When the urine is stored in the bladder, these chemicals are in contact with the bladder lining.

- Chemicals called arylamines are known to cause bladder cancer. Arylamines in cigarette smoke may be the cause of the increased risk.

Chemicals at work

If you have been diagnosed with bladder cancer, it’s worth talking to your urologist or cancer doctor to find out if it could be linked to chemicals in your workplace.

Certain industrial chemicals have been linked with bladder cancer. Chemicals called aromatic amines, such as benzidine and beta-naphthylamine, which are sometimes used in the dye industry, can cause bladder cancer.

Workers in other industries that use certain organic chemicals also may have a higher risk of bladder cancer. Industries carrying higher risks include makers of rubber, leather, textiles, and paint products as well as printing companies. Other workers with an increased risk of developing bladder cancer include painters, machinists, printers, hairdressers (probably because of heavy exposure to hair dyes), and truck drivers (likely because of exposure to diesel fumes).

Cigarette smoking and workplace exposures can act together to cause bladder cancer. So, people who smoke who also work with cancer-causing chemicals have an especially high risk of bladder cancer.

- Arylamines: This is a group of chemicals known to cause bladder cancer. Some of these chemicals have been banned for over 50 years. But you may have been exposed to them if you work in industries that produce dyes, rubber, textiles, chemicals or plastics. It can take around 30 years or more for a bladder cancer to develop.

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: These are a group of chemicals that might increase the risk of bladder cancer. You may have been exposed to them if you have worked in:

- industries where people handle carbon or crude oil, or substances made from them

- any industry involving combustion, such as smelting

Employers have a legal duty to protect the health and safety of their employees under law.

Certain medicines or herbal supplements

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), use of the diabetes medicine pioglitazone (Actos®) is linked with an increased risk of bladder cancer. The risk seems to get higher when higher doses are used.

Dietary supplements containing aristolochic acid (mainly in herbs from the Aristolochia family) have been linked with an increased risk of urothelial cancers, including bladder cancer.

Arsenic in drinking water

Arsenic in drinking water has been linked with a higher risk of bladder cancer in some parts of the world. The chance of being exposed to arsenic depends on where you live and whether you get your water from a well or from a public water system that meets the standards for low arsenic content. For most Americans, drinking water isn’t a major source of arsenic.

Not drinking enough fluids

People who drink a lot of fluids, especially water, each day tend to have lower rates of bladder cancer. This might be because they empty their bladders more often, which could keep chemicals from lingering in their bladder.

Being overweight

Some research has shown that you may be at an increased risk of getting bladder cancer if you’re overweight or obese. But more research is needed and it’s unclear how much of an increased risk there may be.

Risk factors you cannot change

Race and ethnicity

Whites are about twice as likely to develop bladder cancer as African Americans and Hispanics. Asian Americans and American Indians have slightly lower rates of bladder cancer. The reasons for these differences are not well understood.

Age

The risk of bladder cancer increases with age. About 9 out of 10 people with bladder cancer are older than 55.

Gender

Bladder cancer is much more common in men than in women.

Chronic bladder irritation and infections

Research shows that having many bladder infections or long lasting infections can increase your risk of developing bladder cancer. Urinary infections, gonorrhoea, kidney and bladder stones, bladder catheters left in place a long time, and other causes of chronic (ongoing) bladder irritation have been linked to bladder cancer especially squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. But it’s not really known how or why this happens.

Schistosomiasis also known as bilharziasis, an infection with a parasitic worm that can get into the bladder, is also a risk factor for bladder cancer. In countries where this parasite is common (mainly in Africa and the Middle East), squamous cell cancers of the bladder are much more common. This is an extremely rare cause of bladder cancer in the United States.

Having had bladder cancer before

Your risk of developing another cancer anywhere in the urinary tract is higher if you have previously been treated for bladder cancer. This includes:

- any part of your bladder that is still there after your treatment

- the tubes that connect the kidney and the bladder (the ureters) including the part within the kidney (the renal pelvis)

- the tube leading from the bladder to the outside of the body (urethra)

Having had transitional cell cancer of other parts of the urinary tract (such as the ureters, urethra or renal pelvis) also increases your risk of getting bladder cancer.

Other cancers have been linked to an increased risk of bladder cancer. These include head and neck cancers, lung cancer and kidney cancer. Cancer treatment such as radiotherapy may increase your risk or it may be that these cancers share risk factors with bladder cancer.

For this reason, people who have had bladder cancer need careful follow-up to look for new cancers at its earliest stage.

Bladder birth defects

Before birth, there’s a connection between the belly button and the bladder. This is called the urachus. If part of this connection remains after birth, it could become cancer. Cancers that start in the urachus are usually adenocarcinomas, which are made up of cancerous gland cells. About one-third of the adenocarcinomas of the bladder start here. But this is still rare, accounting for less than half of 1% of all bladder cancers.

Another rare birth defect called exstrophy greatly increases a person’s risk of bladder cancer. In bladder exstrophy, both the bladder and the abdominal wall in front of the bladder don’t close completely during fetal development and are fused together. This leaves the inner lining of the bladder exposed outside the body. Surgery soon after birth can close the bladder and abdominal wall (and repair other related defects), but people who have this still have a higher risk for urinary infections and bladder cancer.

Genetics and family history

People who have family members with bladder cancer have a higher risk of getting it themselves. Sometimes this may be because the family members are exposed to the same cancer-causing chemicals (like those in tobacco smoke). They may also share changes in some genes (like GST and NAT) that make it hard for their bodies to break down certain toxins, which can make them more likely to get bladder cancer.

A small number of people inherit a gene syndrome that increases their risk for bladder cancer. For example:

- A mutation of the retinoblastoma (RB1) gene can cause cancer of the eye in infants, and also increases the risk of bladder cancer.

- Cowden disease, caused by mutations in the PTEN gene, is linked mainly to cancers of the breast and thyroid. People with this disease also have a higher risk of bladder cancer.

- Lynch syndrome also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is linked mainly to colon and endometrial cancer. People with this syndrome might also have an increased risk of bladder cancer (as well as other cancers of the urinary tract).

Prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy

Taking the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) for a long time can irritate the bladder and increase the risk of bladder cancer. People taking this drug are often told to drink plenty of fluids to help protect the bladder from irritation.

People who are treated with radiation to the pelvis are more likely to develop bladder cancer.

Systemic sclerosis

Women who have systemic sclerosis have a higher risk of getting bladder cancer than the general public. This may be due to a drug called cyclophosphamide, which is used to treat the condition.

Kidney transplant

People who have had a kidney transplant have a higher risk of getting bladder cancer than the general public.

Bladder Cancer Prevention

There is no sure way to prevent bladder cancer. Some risk factors such as age, gender, race, and family history can’t be controlled. But there might be things you can do that could help lower your risk.

Don’t smoke

Smoking is thought to cause about half of all bladder cancers. This includes any type of smoking — cigarettes, cigars, or pipes.

Limit exposure to certain chemicals in the workplace

Workers in industries that use certain organic chemicals have a higher risk of bladder cancer. Workplaces where these chemicals are commonly used include the rubber, leather, printing materials, textiles, and paint industries. If you work in a place where you might be exposed to such chemicals, be sure to follow good work safety practices.

Some chemicals found in certain hair dyes might also increase risk, so it’s important for hairdressers and barbers who are exposed to these products regularly to use them safely. Most studies have not found that personal use of hair dyes increases bladder cancer risk.

Some research has suggested that people exposed to diesel fumes in the workplace might also have a higher risk of bladder cancer (as well as some other cancers), so limiting this exposure might be helpful.

Drink plenty of liquids

There is some evidence that drinking a lot of fluids – mainly water – might lower a person’s risk of bladder cancer.

Eat lots of fruits and vegetables

Some studies have suggested that a diet high in fruits and vegetables might help protect against bladder cancer, but other studies have not found this. Still, eating a healthy diet has been shown to have many benefits, including lowering the risk of some other types of cancer.

Can Bladder Cancer Be Found Early?

Bladder cancer can sometimes be found early — when it’s small and hasn’t spread beyond the bladder. Finding it early improves your chances that treatment will work.

Screening for bladder cancer

Screening is the use of tests or exams to look for a disease in people who have no symptoms. At this time, no major professional organizations recommend routine screening of the general public for bladder cancer. This is because no screening test has been shown to lower the risk of dying from bladder cancer in people who are at average risk.

Some doctors may recommend bladder cancer tests for people at very high risk, such as:

- People who had bladder cancer before

- People who had certain birth defects of the bladder

- People exposed to certain chemicals at work

Tests that might be used to look for bladder cancer

Tests for bladder cancer look for different substances and/or cancer cells in the urine.

- Urinalysis: One way to test for bladder cancer is to check for blood in the urine (hematuria). This can be done during a urinalysis, which is a simple test to check for blood and other substances in a sample of urine. This test is sometimes done as part of a general health check-up. Blood in the urine is usually caused by benign (non-cancer) problems, like infections, but it also can be the first sign of bladder cancer. Large amounts of blood in urine can be seen if the urine turns pink or red, but a urinalysis can find even small amounts. Urinalysis can help find some bladder cancers early, but it has not been shown to be useful as a routine screening test.

- Urine cytology: In this test, a microscope is used to look for cancer cells in urine. Urine cytology does find some cancers, but it’s not reliable enough to make a good screening test.

- Urine tests for tumor markers: Several newer tests look for substances in the urine that might indicate bladder cancer. These include:

- UroVysion™: This test looks for chromosome changes that are often seen in bladder cancer cells.

- BTA tests: These tests look for a substance called bladder tumor-associated antigen (BTA), also known as CFHrp, in the urine.

- Immunocyt™: This test looks at cells in the urine for the presence of substances such as mucin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which are often found on cancer cells.

- NMP22 BladderChek®: This test looks for a protein called NMP22 in the urine, which is often found at higher levels in people who have bladder cancer.

These tests might find some bladder cancers early, but they can miss some as well. In other cases, the test result might be abnormal even in some people who do not have cancer. At this time the tests are used mainly to look for bladder cancer in people who already have signs or symptoms of cancer, or in people who have had a bladder cancer removed to check for cancer recurrence. Further research is needed before these or other newer tests are proven useful as screening tests.

Watching for possible symptoms of bladder cancer

While no screening tests are recommended for people at average risk, bladder cancer can often be found early because it causes blood in the urine or other urinary symptoms. Many of these symptoms often have less serious causes, but it’s important to have them checked by a doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed. If the symptoms are from bladder cancer, finding it early offers the best chance for successful treatment.

Bladder cancer diagnosis

Bladder cancer is often found because of signs or symptoms a person is having such as blood in your urine or it might be found because of lab tests a person gets for another reason. If bladder cancer is suspected, exams and tests will be needed to confirm the diagnosis. If cancer is found, further tests will be done to help determine the extent (stage) of the cancer.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose bladder cancer may include:

- Using a scope to examine the inside of your bladder (cystoscopy). To perform cystoscopy, your doctor inserts a small, narrow tube (cystoscope) through your urethra. The cystoscope has a lens that allows your doctor to see the inside of your urethra and bladder, to examine these structures for signs of disease. Cystoscopy can be done in a doctor’s office or in the hospital.

- Removing a sample of tissue for testing (biopsy). During cystoscopy, your doctor may pass a special tool through the scope and into your bladder to collect a cell sample (biopsy) for testing. This procedure is sometimes called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). TURBT can also be used to treat bladder cancer.

- Examining a urine sample (urine cytology). A sample of your urine is analyzed under a microscope to check for cancer cells in a procedure called urine cytology.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests, such as computerized tomography (CT) urogram or retrograde pyelogram, allow your doctor to examine the structures of your urinary tract.

- During a CT urogram, a contrast dye injected into a vein in your hand eventually flows into your kidneys, ureters and bladder. X-ray images taken during the test provide a detailed view of your urinary tract and help your doctor identify any areas that might be cancer.

- Retrograde pyelogram is an X-ray exam used to get a detailed look at the upper urinary tract. During this test, your doctor threads a thin tube (catheter) through your urethra and into your bladder to inject contrast dye into your ureters. The dye then flows into your kidneys while X-ray images are captured.

After confirming that you have bladder cancer, your doctor may recommend additional tests to determine whether your cancer has spread to your lymph nodes or to other areas of your body.

Tests may include:

- CT scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Positron emission tomography (PET)

- Bone scan

- Chest X-ray

Medical history and physical exam

Your doctor will want to get your medical history to learn more about your symptoms. The doctor might also ask about possible risk factors, including your family history.

A physical exam can provide other information about possible signs of bladder cancer and other health problems. The doctor might do a digital rectal exam, during which a gloved, lubricated finger is put into your rectum. If you are a woman, the doctor might do a pelvic exam as well. During these exams, the doctor can sometimes feel a bladder tumor, determine its size, and feel if and how far it has spread.

If the results of the exam are abnormal, your doctor will probably do lab tests and might refer you to a urologist (a doctor specializing in diseases of the urinary system and male reproductive system) for further tests and treatment.

Urine lab tests

- Urinalysis: This is a simple test to check for blood and other substances in a sample of urine.

- Urine cytology: For this test, a sample of urine is looked at with a microscope to see if it has any cancer or pre-cancer cells. Cytology is also done on any bladder washings taken during a cystoscopy. Cytology can help find some cancers, but this test is not perfect. Not finding cancer on this test doesn’t always mean you are cancer free.

- Urine culture: If you are having urinary symptoms, this test may be done to see if an infection (rather than cancer) is the cause. Urinary tract infections and bladder cancers can have similar symptoms. For a urine culture, a sample of urine is put into a dish in the lab to allow any bacteria that are present to grow. It can take time for the bacteria to grow, so it may take a few days to get the results of this test.

- Urine tumor marker tests: Different urine tests look for specific substances released by bladder cancer cells. One or more of these tests may be used along with urine cytology to help determine if you have bladder cancer. These include the tests for NMP22 (BladderChek) and BTA (BTA stat), the Immunocyt test, and the UroVysion test. Some doctors find these urine tests useful in looking for bladder cancers, but they may not help in all cases. Most doctors feel that cystoscopy is still the best way to find bladder cancer. Some of these tests are more helpful when looking for a possible recurrence of bladder cancer in someone who has already had it, rather than finding it in the first place.

Cystoscopy

If bladder cancer is suspected, doctors will recommend a cystoscopy. For this exam, a urologist places a cystoscope – a thin tube with a light and a lens or a small video camera on the end – through the opening of the urethra and advances it into the bladder. Sterile salt water is then injected through the scope to expand the bladder and allow the doctor to look at its inner lining.

Cystoscopy can be done in a doctor’s office or in an operating room. Usually the first cystoscopy will be done in the doctor’s office using a small, flexible fiber-optic device. Some sort of local anesthesia may be used to numb the urethra and bladder for the procedure. If the cystoscopy is done using general anesthesia (where you are asleep) or spinal anesthesia (where the lower part of your body is numbed), the procedure is done in the operating room.

Fluorescence cystoscopy (also known as blue light cystoscopy) may be done along with routine cystoscopy. For this exam, a light-activated drug is put into the bladder during cystoscopy. It is taken up by cancer cells. When the doctor then shines a blue light through the cystoscope, any cells containing the drug will glow (fluoresce). This can help the doctor see abnormal areas that might have been missed by the white light normally used.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor

If an abnormal area (or areas) is seen during a cystoscopy, it will be biopsied to see if it is cancer. A biopsy is the removal of small samples of body tissue to see if it is cancer. If bladder cancer is suspected, a biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

The procedure used to biopsy an abnormal area is a transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT), also known as just a transurethral resection (TUR). During this procedure, the doctor removes the tumor and some of the bladder muscle near the tumor. The removed samples are then sent to a lab to look for cancer. If cancer is found, this can also show if it has invaded into the muscle layer of the bladder wall.

Bladder cancer can sometimes develop in more than one area of the bladder (or in other parts of the urinary tract). Because of this, the doctor may take samples from several different areas of the bladder, especially if cancer is strongly suspected but no tumor can be seen. Salt water washings of the inside the bladder may also be collected to look for cancer cells.

Biopsy results

The biopsy samples are sent to a lab, where they are looked at by a pathologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing diseases with lab tests. If bladder cancer is found, two important features are its invasiveness and grade.

Invasiveness

The biopsy can show how deeply the cancer has invaded (grown into) the bladder wall which is very important in deciding treatment.

- If the cancer stays in the inner layer of cells without growing into the deeper layers, it is called non-invasive.

- If the cancer grows into the deeper layers of the bladder, it is called invasive.

Invasive cancers are more likely to spread and are harder to treat.

You may also see a bladder cancer described as superficial or non-muscle invasive. These terms include both non-invasive tumors as well as any invasive tumors that have not grown into the main muscle layer of the bladder.

Bladder cancer grades

Bladder cancers are also assigned a grade, based on how much the cancer cells look like normal cells under the microscope. Bladder cancer grades tells your doctor how the cancer might behave and what treatment you need.

To find the grade of cancer cells, doctors take tissue samples (biopsies) and send them to the laboratory. A specialist (pathologist) looks at them using a microscope.

Bladder cancer cells are often divided into 3 grades:

- Grade 1 bladder cancer: The cancers cells look very like normal cells. They are called low grade or well differentiated. They tend to grow slowly and generally stay in the lining of the bladder.

- Grade 2 bladder cancer: The cancer cells look less like normal cells (abnormal). They are called moderately differentiated. They are more likely to spread into the deeper (muscle) layer of the bladder or to come back after treatment.

- Grade 3 bladder cancer: The cancer cells look very abnormal. They are called high grade or poorly differentiated. They grow more quickly and are more likely to come back after treatment or spread into the deeper (muscle) layer of the bladder.

Bladder cancer can also be described as either low grade or high grade:

- Low-grade cancers look more like normal bladder tissue. They are also called well-differentiated cancers. Low grade is the same as grade 1. Low grade bladder cancer means that your cancer is less likely to grow, spread and come back after treatment. Patients with these cancers usually have a good prognosis (outlook).

- High-grade cancers look less like normal tissue. These cancers may also be called poorly differentiated or undifferentiated. High grade is the same as grade 3. High-grade cancers are more likely to grow into the bladder wall and to spread outside the bladder. These cancers can be harder to treat and come back after treatment.

For example, if you have early (superficial) bladder cancer but the cells are high grade, you’re more likely to need further treatment after surgery. This is to reduce the risk of your cancer coming back.

Another grading system (World Health Organisation [WHO] grades) is sometimes used for early bladder cancer. This divides bladder cancers into 4 groups:

- Urothelial papilloma means it is a non cancerous (benign) tumor

- Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) means it is a very slow growing tumor that is unlikely to spread

- Low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is a slow growing cancer that is unlikely to spread

- High grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is a quicker growing cancer that is more likely to spread

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, sound waves, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body.

If you have bladder cancer, your doctor may order some of these tests to see if the cancer has spread to structures near the bladder, to nearby lymph nodes, or to distant organs. If an imaging test shows enlarged lymph nodes or other possible signs of cancer spread, some type of biopsy might be needed to confirm the findings.

Intravenous pyelogram (IVP)

An intravenous pyelogram (IVP), also called an intravenous urogram (IVU), is an x-ray of the urinary system taken after injecting a special dye into a vein. This dye is removed from the bloodstream by the kidneys and then passes into the ureters and bladder. The dye outlines these organs on x-rays and helps show urinary tract tumors.

It’s important to tell your doctor if you have any allergies or have ever had a reaction to x-ray dyes, or if you have any type of kidney problems. If so, your doctor might choose to do another test instead.

Retrograde pyelogram

For this test, a catheter (thin tube) is placed through the urethra and up into the bladder or into a ureter. Then a dye is injected through the catheter to make the lining of the bladder, ureters, and kidneys easier to see on x-rays.

This test isn’t used as often as IVP, but it may be done (along with ultrasound of the kidneys) to look for tumors in the urinary tract in people who can’t have an IVP.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan uses x-rays to make detailed cross-sectional images of your body. A CT scan of the kidney, ureters, and bladder is known as a CT urogram. It can provide detailed information about the size, shape, and position of any tumors in the urinary tract, including the bladder. It can also help show enlarged lymph nodes that might contain cancer, as well as other organs in the abdomen and pelvis.

CT-guided needle biopsy: CT scans can also be used to guide a biopsy needle into a suspected tumor. This is not used to biopsy tumors in the bladder, but it can be used to take samples from areas where the cancer may have spread. For this procedure, you lie on the CT scanning table while the doctor advances a biopsy needle through the skin and into the tumor.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans , MRI scans show detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays.

MRI images are particularly useful in showing if the cancer has spread outside of the bladder into nearby tissues or lymph nodes. A special MRI of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, known as an MRI urogram, can be used instead of an IVP to look at the upper part of the urinary system.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses sound waves to create pictures of internal organs. It can be useful in determining the size of a bladder cancer and whether it has spread beyond the bladder to nearby organs or tissues. It can also be used to look at the kidneys.

This is usually an easy test to have, and it uses no radiation.

Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy: Ultrasound can also be used to guide a biopsy needle into a suspected area of cancer spread in the abdomen or pelvis.

Chest x-ray

A chest x-ray may be done to see if the bladder cancer has spread to the lungs. This test is not needed if a CT scan of the chest has been done.

Bone scan

A bone scan can help look for cancer that has spread to bones. Doctors don’t usually order this test unless you have symptoms such as bone pain, or if blood tests show the cancer might have spread to your bones.

For this test, you get an injection of a small amount of low-level radioactive material, which settles in areas of damaged bone throughout the body. A special camera detects the radioactivity and creates a picture of your skeleton.

A bone scan may suggest cancer in the bone, but to be sure, other imaging tests such as plain x-rays, MRI scans, or even a bone biopsy might be needed.

Biopsies to look for cancer spread

If imaging tests suggest the cancer might have spread outside of the bladder, a biopsy might be needed to be sure.

In some cases, biopsy samples of suspicious areas are obtained during surgery to remove the bladder cancer.

Another way to get a biopsy sample is to use a thin, hollow needle to take a small piece of tissue from the abnormal area. This is known as a needle biopsy, and by using it the doctor can take samples without an operation. Needle biopsies are sometimes done using a CT scan or ultrasound to help guide the biopsy needle into the abnormal area.

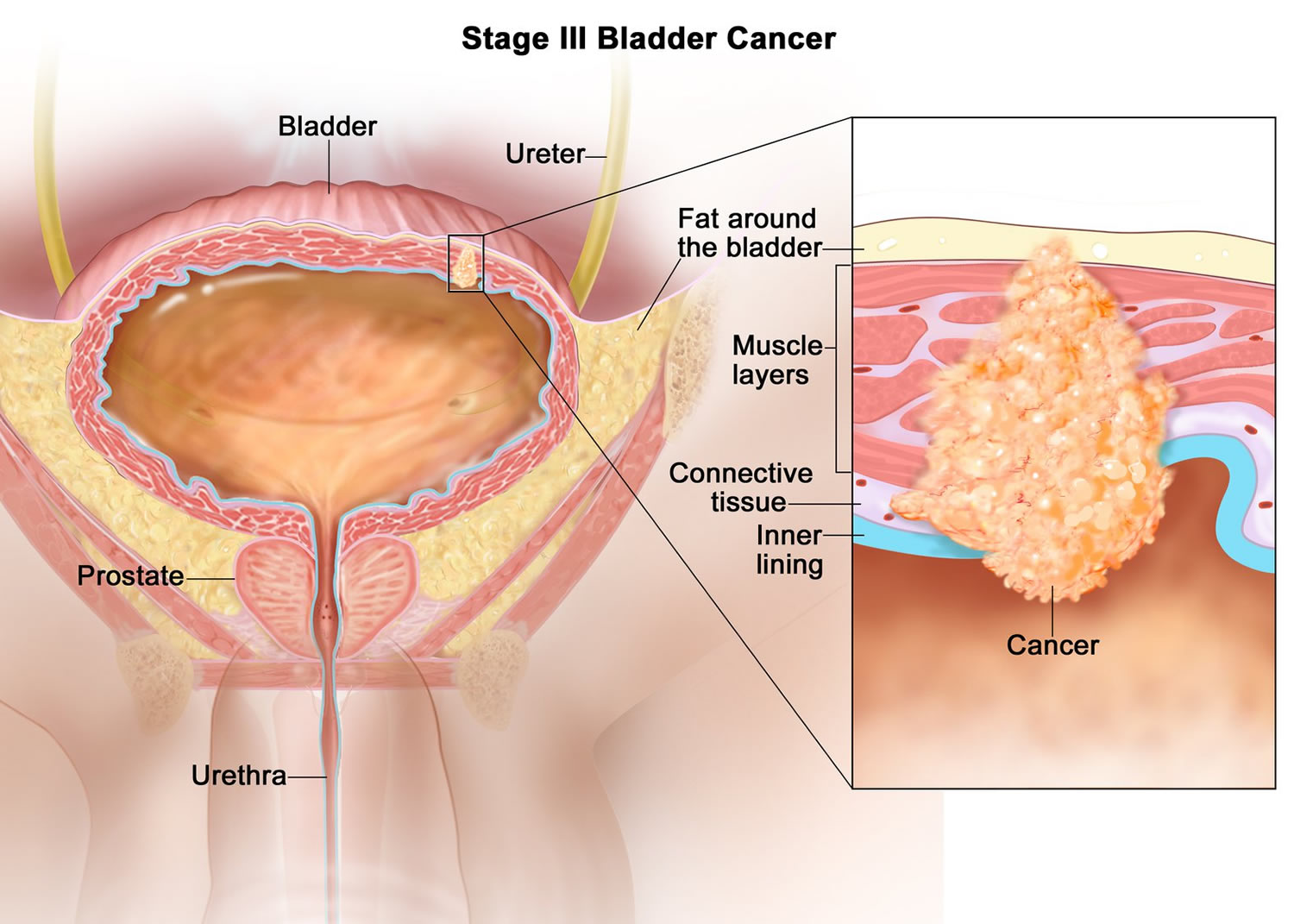

Bladder cancer stages

After someone is diagnosed with bladder cancer, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes the extent (amount) of cancer in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. The stage is one of the most important factors in deciding how to treat the cancer and determining how successful treatment might be. If you have bladder cancer, ask your cancer care team to explain its stage. This can help you make informed choices about your treatment.

There are actually 2 types of stages for bladder cancer:

- The clinical stage is the doctor’s best estimate of the extent of the cancer, based on the results of physical exams, cystoscopy, biopsies, and any imaging tests that are done (such as CT scans). These exams and tests are described in Tests for bladder cancer.

- If surgery is done to treat the cancer, the pathologic stage can be determined using the same factors as the clinical stage, plus what is found during surgery.

The clinical stage is used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread farther than the clinical stage estimates. Pathologic staging is likely to be more accurate, because it gives your doctor a firsthand impression of the extent of your cancer.

A staging system is a standard way for the cancer care team to describe how far a cancer has spread. The staging system most often used for bladder cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- T describes how far the main (primary) tumor has grown through the bladder wall and whether it has grown into nearby tissues.

- N indicates any cancer spread to lymph nodes near the bladder. Lymph nodes are bean-sized collections of immune system cells, to which cancers often spread first.

- M indicates whether or not the cancer has spread (metastasized) to distant sites, such as other organs or lymph nodes that are not near the bladder.

Numbers or letters appear after T, N, and M to provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced.

The T category describes how far the main tumor has grown into the wall of the bladder (or beyond).

The wall of the bladder has 4 main layers.

- The innermost lining is called the urothelium or transitional epithelium.

- Beneath the urothelium is a thin layer of connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves.

- Next is a thick layer of muscle.

- Outside of this muscle, a layer of fatty connective tissue separates the bladder from other nearby organs.

Nearly all bladder cancers start in the urothelium. As the cancer grows into or through the other layers in the bladder, it becomes more advanced.

The T categories are described in the Table 1 below, except for:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor

The N category describes spread only to the lymph nodes near the bladder (in the true pelvis) and those along the blood vessel called the common iliac artery. These lymph nodes are called regional lymph nodes. Any other lymph nodes are considered distant lymph nodes. Spread to distant nodes is considered metastasis (described in the M category). Surgery is usually needed to find cancer spread to lymph nodes, since it is not often seen on imaging tests.

The N categories are described in the Table 1 below, except for:

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- N0: There’s no regional lymph node spread.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

The M category for bladder cancer describes whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) to a different part of the body.

There are 2 M stages:

- M0 means your cancer has not spread to other parts of the body

- M1 means your cancer has spread to other parts of the body. The most common sites are distant lymph nodes, the bones, the lungs, and the liver. Cancer that has spread to other areas of the body, such as the lungs, is called advanced or metastatic bladder cancer.

- M1a means your cancer has spread to the lymph nodes outside the pelvis

- M1b means your cancer has spread to other parts of the body like the bones, lungs and liver

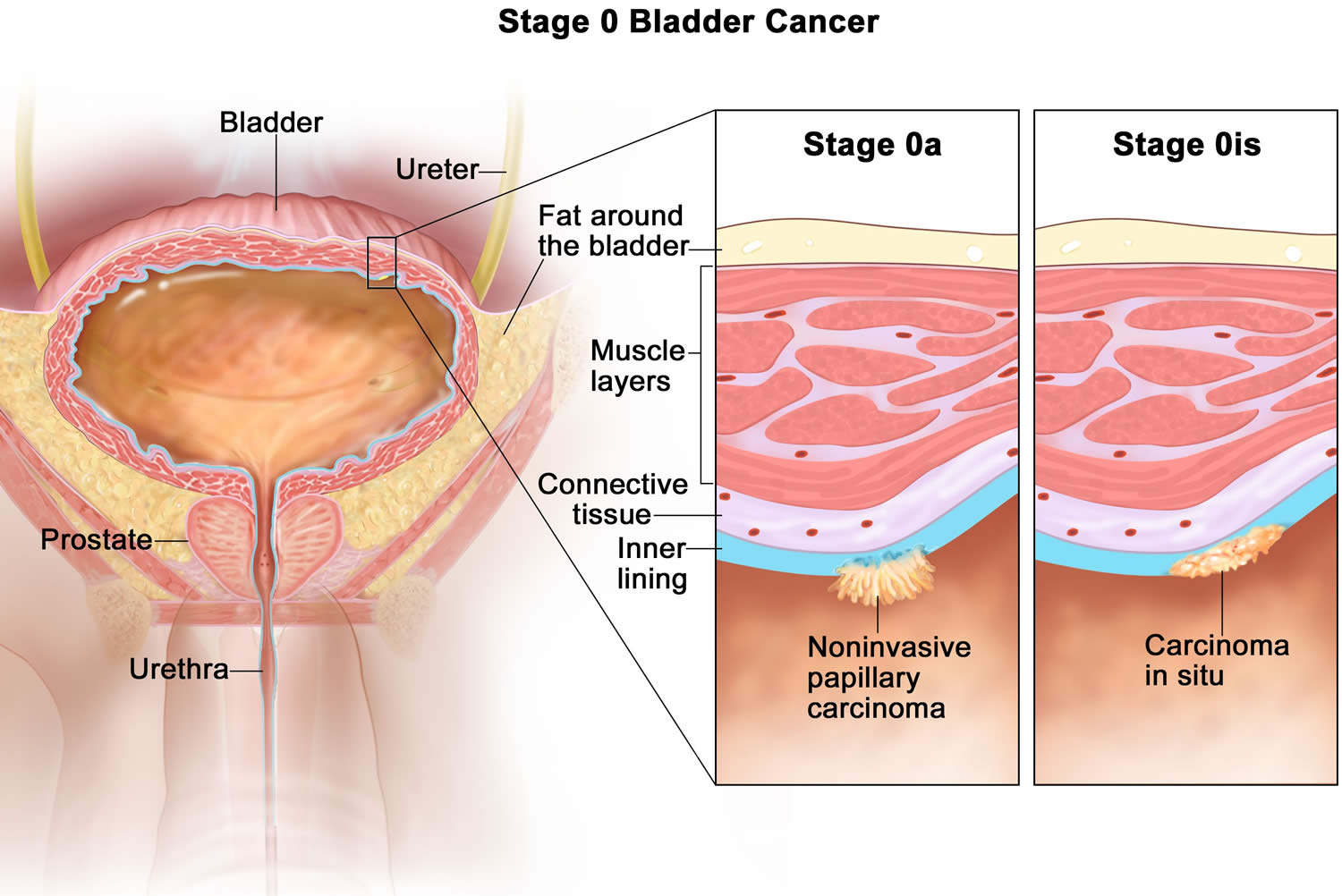

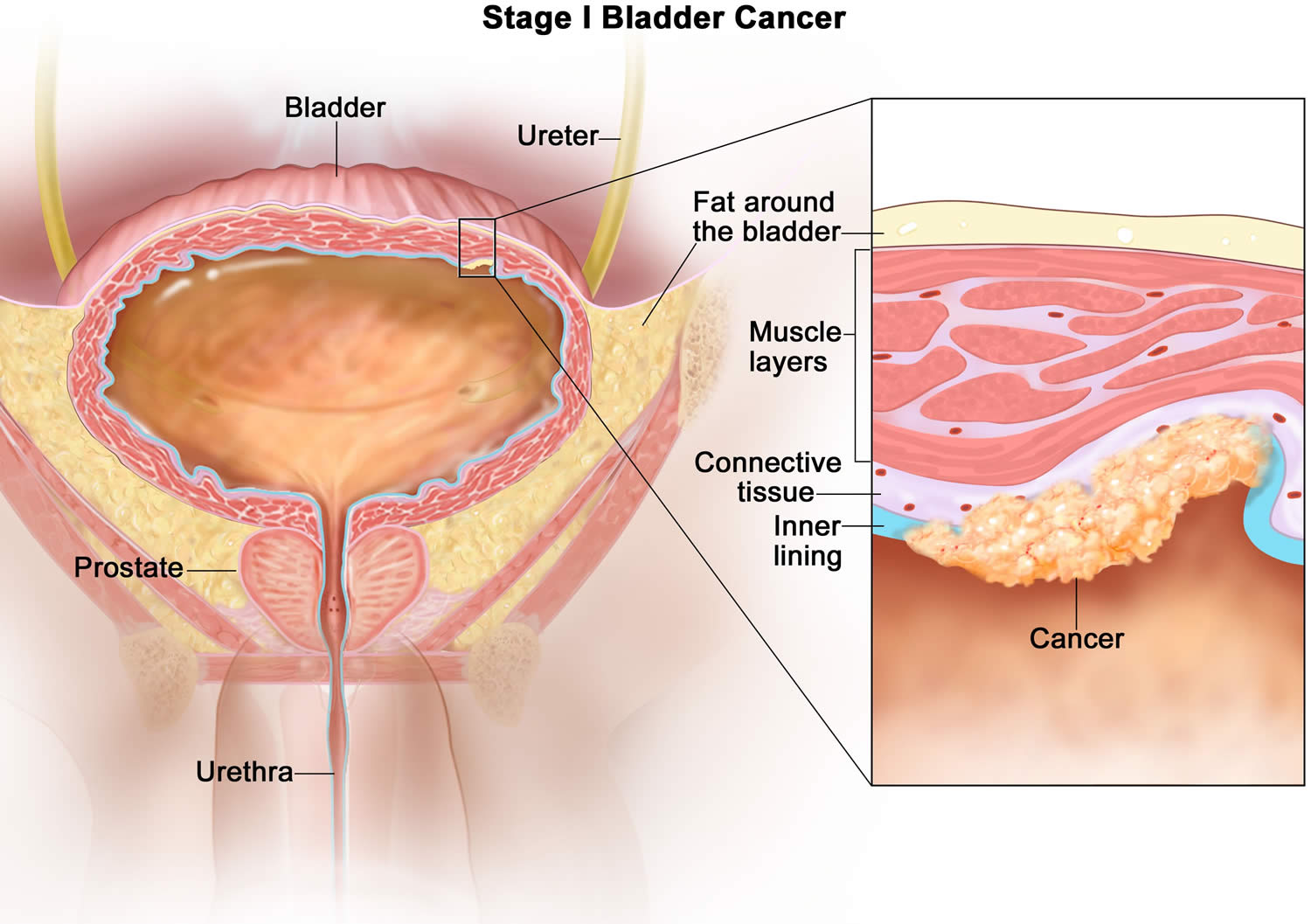

Once the T, N, and M categories have been determined, usually after surgery, this information is combined to find the overall cancer stage. Bladder cancer stages are defined using 0 and the Roman numerals I to IV (1 to 4). Stage 0 (also known as carcinoma in situ) is the earliest stage, while stage IV (4) is the most advanced.

As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means a more advanced cancer. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

TNM staging system

Table 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system

| Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description |

|---|---|---|

| 0a | Ta N0 M0 | The cancer is a non-invasive papillary carcinoma (Ta). It has grown toward the hollow center of the bladder but has not grown into the connective tissue or muscle of the bladder wall. It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). |

| 0is | Tis N0 M0 | The cancer is a flat, non-invasive carcinoma (Tis), also known as flat carcinoma in situ (CIS). The cancer is growing in the inner lining layer of the bladder only. It has not grown inward toward the hollow part of the bladder, nor has it invaded the connective tissue or muscle of the bladder wall. It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0). |

| 1 | T1 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown into the layer of connective tissue under the lining layer of the bladder, but has not reached the layer of muscle in the bladder wall (T1). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

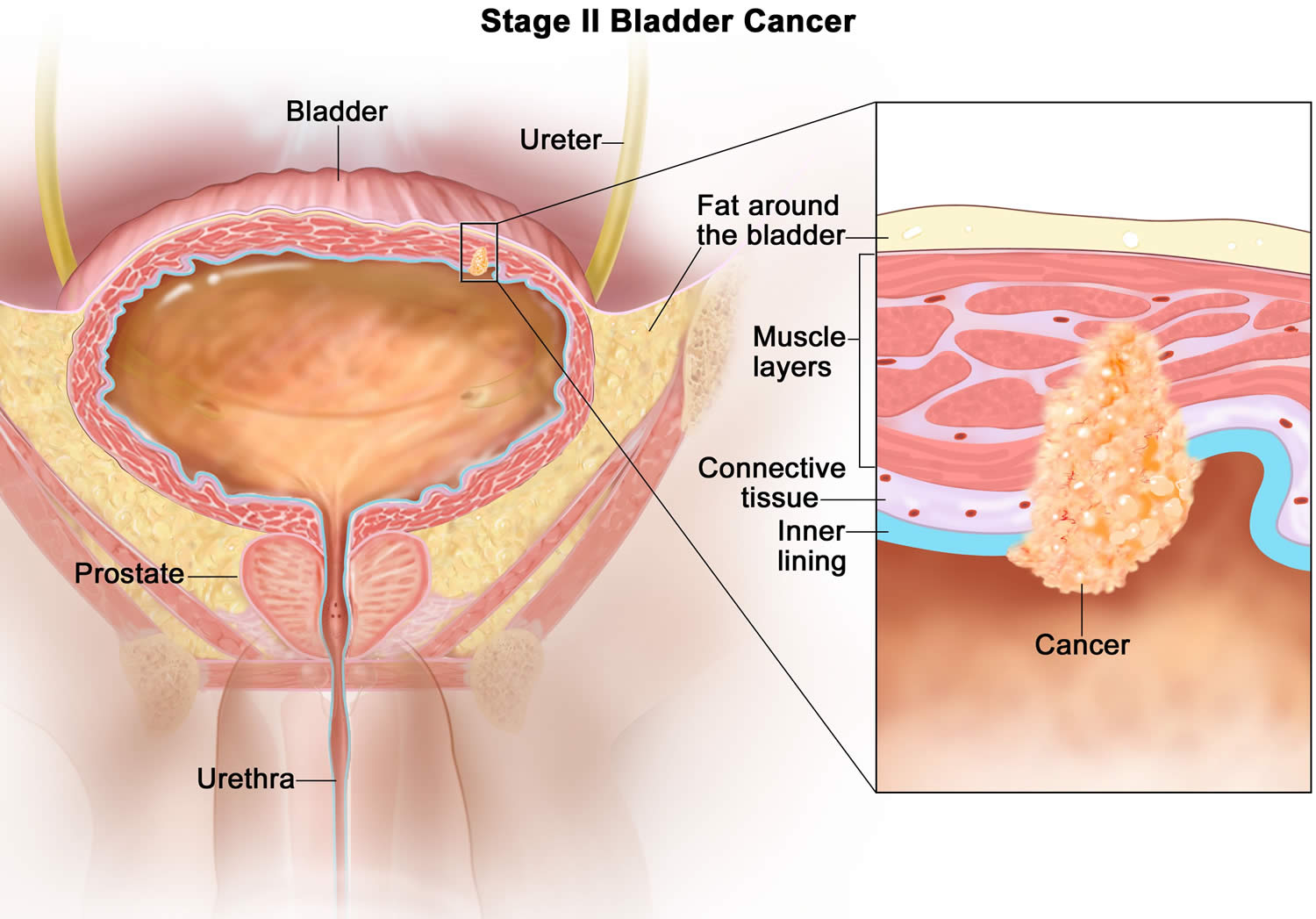

| 2 | T2a or T2b N0 M0 | The cancer has grown into the inner (T2a) or outer (T2b) muscle layer of the bladder wall, but it has not passed completely through the muscle to reach the layer of fatty tissue that surrounds the bladder. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

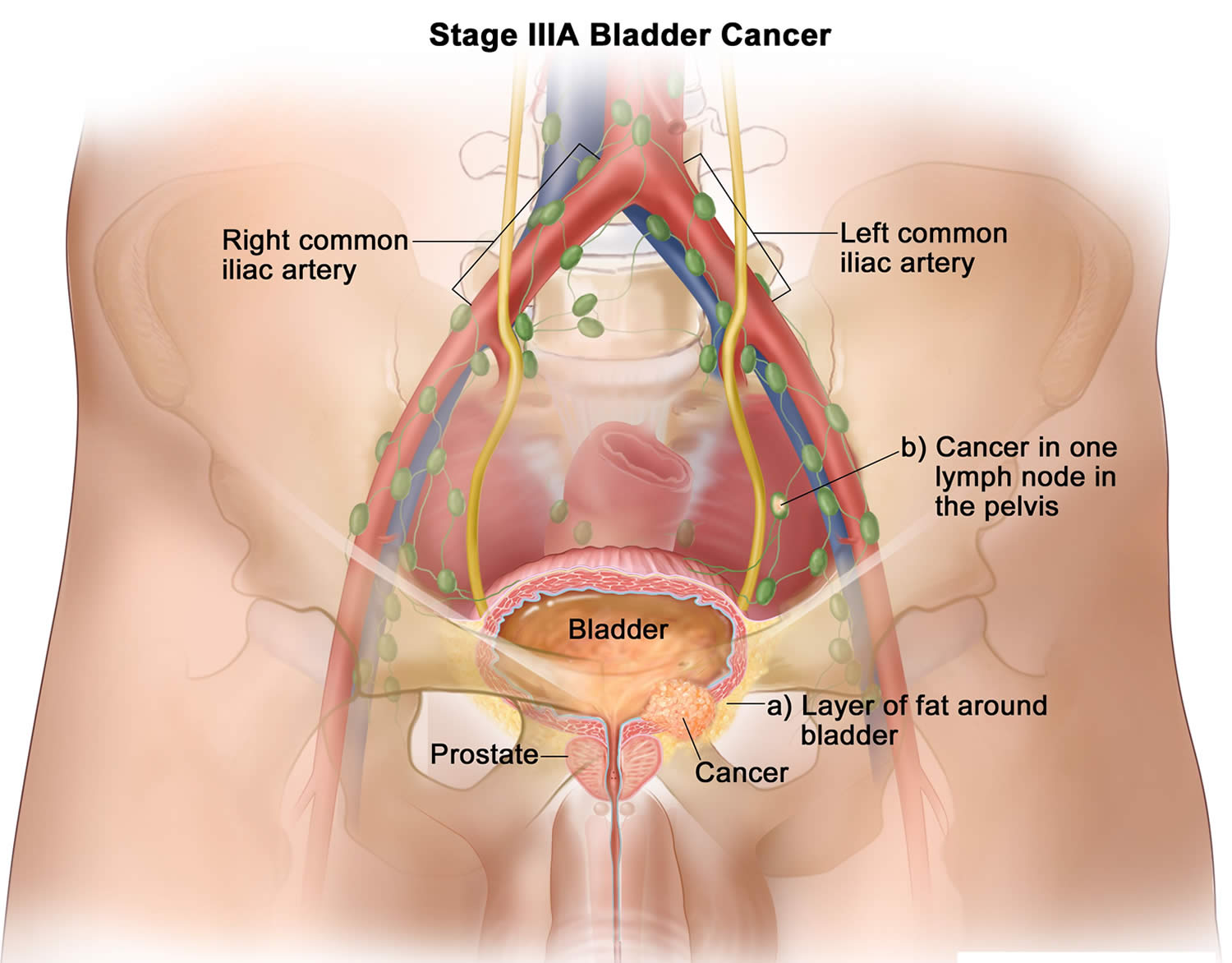

| 3A | T3a, T3b or T4a N0 M0 | The cancer has grown through the muscle layer of the bladder and into the layer of fatty tissue that surrounds the bladder (T3a or T3b). It might have spread into the prostate, seminal vesicles, uterus, or vagina, but it’s not growing into the pelvic or abdominal wall (T4a). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | ||

| T1-4a N1 M0 | The cancer has: grown into the layer of connective tissue under the lining of the bladder wall (T1), OR into the muscle layer of the bladder wall (T2), OR into the layer of fatty tissue that surrounds the bladder, (T3a or T3b) OR it might have spread into the prostate, seminal vesicles, uterus, or vagina, but it’s not growing into the pelvic or abdominal wall (T4a). AND the cancer has spread to 1 nearby lymph node in the true pelvis (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). | |

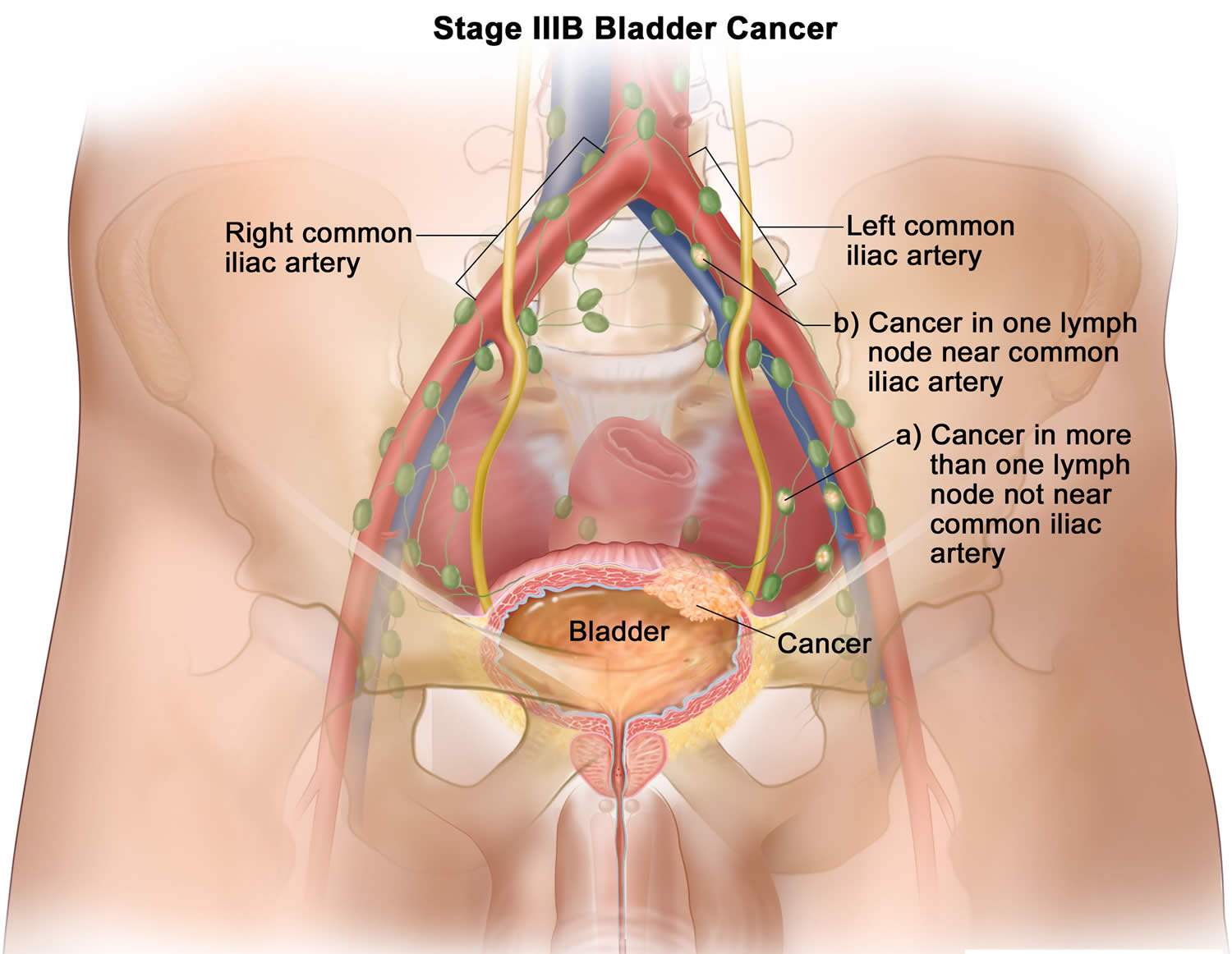

| 3B | T1-T4a N2 or N3 M0 | The cancer has: grown into the layer of connective tissue under the lining of the bladder wall (T1), OR into the muscle layer of the bladder wall (T2), OR into the layer of fatty tissue that surrounds the bladder (T3a or T3b), OR it might have spread into the prostate, seminal vesicles, uterus, or vagina, but it’s not growing into the pelvic or abdominal wall (T4a). AND the cancer has spread to 2 or more lymph nodes in the true pelvis (N2) or to lymph nodes along the common iliac arteries (N3). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

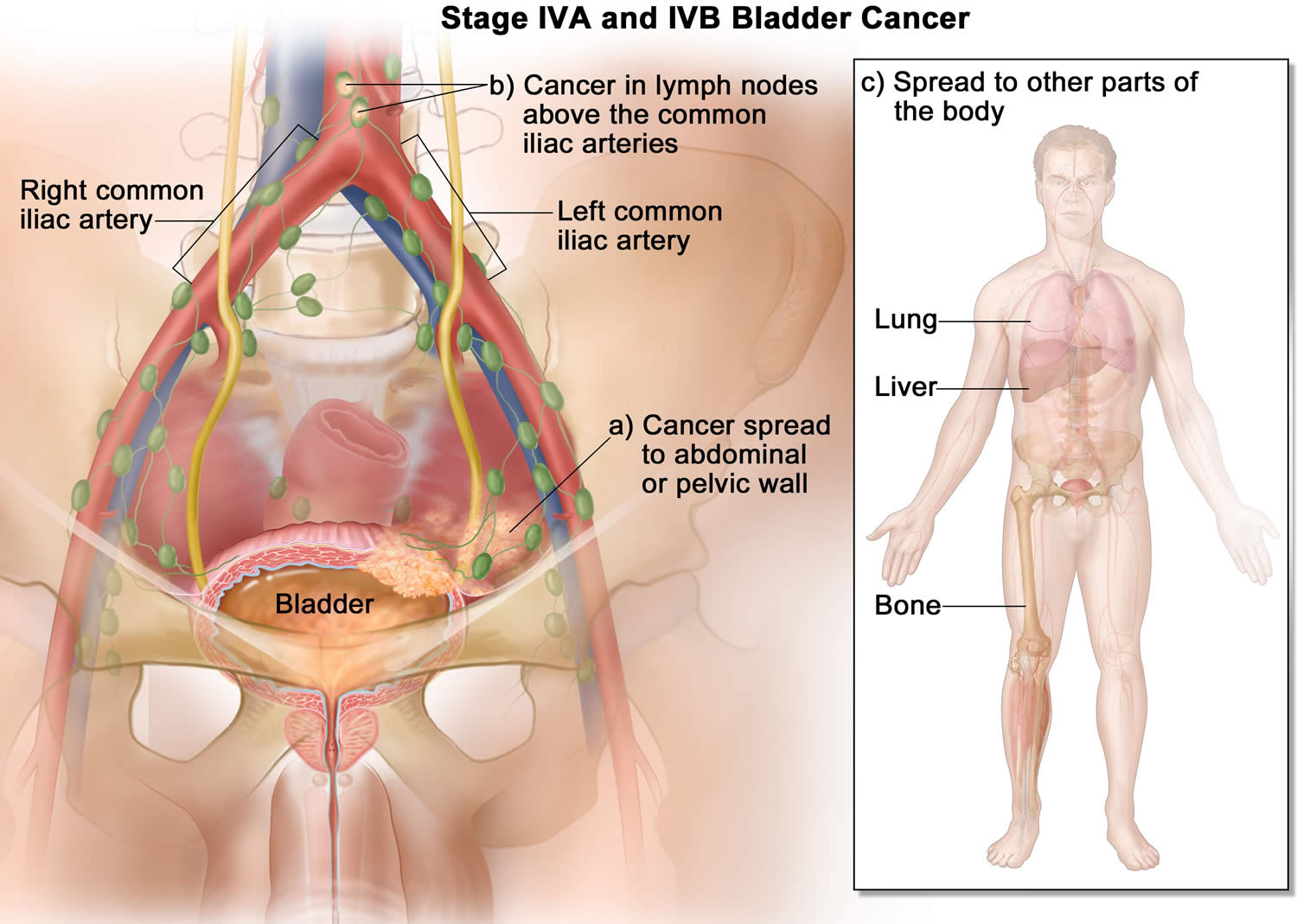

| 4A | T4b Any N M0 | The cancer has grown through the bladder wall into the pelvic or abdominal wall (T4b). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). |

| OR | ||

| Any T Any N M1a | The cancer might or might not have grown through the wall of the bladder into nearby organs (Any T). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to distant lymph nodes (M1a). | |

| 4B | Any T Any N M1b | The cancer might or might not have grown through the wall of the bladder into nearby organs (Any T). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). It has spread to 1 or more distant organs, such as the bones, liver, or lungs (M1b). |

Stage 0 bladder cancer

In stage 0, abnormal cells are found in tissue lining the inside of the bladder. These abnormal cells may become cancer and spread into nearby normal tissue. Stage 0 is divided into stages 0a and 0is, depending on the type of the tumor:

- Stage 0a is also called noninvasive papillary carcinoma, which may look like long, thin growths growing from the lining of the bladder.

- Stage 0is is also called carcinoma in situ (CIS), which is a flat tumor on the tissue lining the inside of the bladder.

Stage 1 bladder cancer

In stage 1 bladder cancer, the cancer has formed and spread to the layer of connective tissue next to the inner lining of the bladder.

Stage 2 bladder cancer

In stage 2 bladder cancer, the cancer has grown through the connective tissue layer into the muscle of the bladder wall.

Stage 3 bladder cancer

Stage 3 bladder cancer is divided into stages 3A and 3B.

- In stage 3A bladder cancer, the cancer has spread from the bladder to the layer of fat surrounding the bladder and may have spread to the reproductive organs (prostate, seminal vesicles, uterus, or vagina) and cancer has not spread to lymph nodes; OR the cancer has spread from the bladder to one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries (major arteries in the pelvis).

- In stage 3B bladder cancer, the cancer has spread from the bladder to more than one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries or to at least one lymph node that is near the common iliac arteries.

Footnote: Stage 3A bladder cancer. Cancer has spread from the bladder to (a) the layer of fat around the bladder and may have spread to the prostate and/or seminal vesicles in men or the uterus and/or vagina in women, and cancer has not spread to lymph nodes; or (b) one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries.

Footnote: Stage 3B bladder cancer. Cancer has spread from the bladder to (a) more than one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries; or (b) at least one lymph node that is near the common iliac arteries.

Stage 4 bladder cancer

Stage 4 bladder cancer is divided into stages 4A and 4B.

- In stage 4A bladder cancer, the cancer has spread from the bladder to the wall of the abdomen or pelvis; OR the cancer has spread to lymph nodes that are above the common iliac arteries (major arteries in the pelvis).

- In stage 4B bladder cancer, the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the lung, bone, or liver.

Footnotes: Stage 4A and 4B bladder cancer. In stage 4A bladder cancer, the cancer has spread from the bladder to (a) the wall of the abdomen or pelvis; or (b) lymph nodes above the common iliac arteries. In stage 4B bladder cancer, the cancer has spread to (c) other parts of the body, such as the lung, liver, or bone.

Bladder cancer survival rates

Survival rates tell you what portion of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding about how likely it is that your treatment will be successful. Some people will want to know the survival rates for their cancer, and some people won’t.

Cancer survival rates don’t tell the whole story

Survival rates are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had the disease, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. There are a number of limitations to remember:

- The numbers below are among the most current available. But to get 5-year survival rates, doctors have to look at people who were treated at least 5 years ago. As treatments are improving over time, people who are now being diagnosed with bladder cancer may have a better outlook than these statistics show.

- These statistics are based on the stage of the cancer when it was first diagnosed. They do not apply to cancers that later come back or spread, for example.

- The outlook for people with bladder cancer varies by the stage (extent) of the cancer – in general, the survival rates are higher for people with earlier stage cancers. But many other factors can affect a person’s outlook, such as age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment. The outlook for each person is specific to their circumstances.

Your doctor can tell you how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your particular situation.

Survival rates for bladder cancer

According to the most recent data, when including all stages of bladder cancer:

- The 5-year relative survival rate is about 77.1%

- The 10-year relative survival rate is about 70%

- The 15-year relative survival rate is about 65%

Keep in mind that just as 5-year survival rates are based on people diagnosed and first treated more than 5 years ago, 10-year survival rates are based on people diagnosed more than 10 years ago (and 15-year survival rates are based on people diagnosed at least 15 years ago).

Bladder cancer survival rates by stage

The numbers below are based on thousands of people diagnosed with bladder cancer from 2011 to 2017. These numbers come from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database 7. The SEER database tracks 5-year relative survival rates for bladder cancer in the United States, based on how far the cancer has spread. The SEER database, however, does not group cancers by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, etc.). Instead, it groups cancers into localized, regional, and distant stages:

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the bladder.

- Regional: The cancer has spread from the bladder to nearby structures or lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body such as the lungs, liver or bones.

Table 2. 5-year relative survival rates for bladder cancer

| SEER Stage | 5-year Relative Survival Rate |

|---|---|

| In situ alone Localized | 96% 70% |

| Regional | 38.00% |

| Distant | 6.00% |

| All SEER stages combined | 77.00% |

Footnotes:

- Based on people diagnosed with bladder cancer between 2011 and 2017.

- Remember, these survival rates are only estimates – they can’t predict what will happen to any individual person. We understand that these statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk to your doctor to better understand your specific situation.

- People now being diagnosed with bladder cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, and other factors will also affect your outlook.

Bladder cancer prognosis

Bladder cancer prognosis depends on the following:

- The stage of the cancer (whether it is superficial or invasive bladder cancer, and whether it has spread to other places in the body). Bladder cancer in the early stages can often be cured.

- The type of bladder cancer cells and how they look under a microscope.

- Whether there is carcinoma in situ in other parts of the bladder.

- Your age and general health.

If the cancer is superficial, prognosis also depends on the following:

- How many tumors there are.

- The size of the tumors.

- Whether the tumor has recurred (come back) after treatment.

No one can tell you exactly how long you will live. Below are general statistics based on large groups of people. Remember, they can’t tell you what will happen in your individual case.

There are no US-wide statistics available for bladder cancer survival by stage. These figures are for men and women diagnosed between 2013 and 2017 in the United Kingdom 8.

- Stage 1 bladder cancer: Stage 1 means that the cancer has started to grow into the connective tissue beneath the bladder lining. Around 80 out of 100 people (around 80%) survive their cancer for 5 years or more after they are diagnosed.

- Stage 2 bladder cancer: Stage 2 means that the cancer has grown through the connective tissue layer into the muscle of the bladder wall. Around 45 out of 100 people (around 45%) survive their cancer for 5 years or more after diagnosis.

- Stage 3 bladder cancer: Stage 3 means that the cancer has grown through the muscle into the fat layer. It may have spread outside the bladder to the prostate, womb or vagina. Around 40 out of 100 people (around 40%) survive their cancer for 5 years or more after they are diagnosed.

- Stage 4 bladder cancer: Stage 4 means that the cancer has spread to the wall of the abdomen or pelvis, the lymph nodes or to other parts of the body. If bladder cancer does spread to another part of the body, it is most likely to go to the bones, lungs or liver. The statistics for stage 4 bladder cancer survival don’t take into account the age of the people with bladder cancer. Statistics that do take into account the age (age-standardized statistics) are not available. Around 10 out of 100 people (around 10%) will survive their stage 4 bladder cancer for 5 years or more after they are diagnosed.

Bladder cancer treatment

Treatment options for bladder cancer depend on a number of factors, including the type of cancer, what the cancer cells look like (the grade), and whether it has spread (the stage of the cancer), which are taken into consideration along with your overall health and your treatment preferences.

Depending on the stage of the cancer and other factors, treatment options for people with bladder cancer can include:

- Surgery to remove the cancer cells

- Transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration: Surgery in which a cystoscope (a thin lighted tube) is inserted into the bladder through the urethra. A tool with a small wire loop on the end is then used to remove the cancer or to burn the tumor away with high-energy electricity. This is known as fulguration.

- Radical cystectomy: Surgery to remove the bladder and any lymph nodes and nearby organs that contain cancer. This surgery may be done when the bladder cancer invades the muscle wall, or when superficial cancer involves a large part of the bladder. In men, the nearby organs that are removed are the prostate and the seminal vesicles. In women, the uterus, the ovaries, and part of the vagina are removed. Sometimes, when the cancer has spread outside the bladder and cannot be completely removed, surgery to remove only the bladder may be done to reduce urinary symptoms caused by the cancer. When the bladder must be removed, the surgeon creates another way for urine to leave the body.

- Partial cystectomy: Surgery to remove part of the bladder. This surgery may be done for patients who have a low-grade tumor that has invaded the wall of the bladder but is limited to one area of the bladder. Because only a part of the bladder is removed, patients are able to urinate normally after recovering from this surgery. This is also called segmental cystectomy.

- Urinary diversion: Surgery to make a new way for the body to store and pass urine.

- Chemotherapy in the bladder also known as intravesical chemotherapy, to treat cancers that are confined to the lining of the bladder but have a high risk of recurrence or progression to a higher stage

- Chemotherapy for the whole body also known as systemic chemotherapy, to increase the chance for a cure in a person having surgery to remove the bladder, or as a primary treatment when surgery isn’t an option

- Radiation therapy also known as radiotherapy, to destroy cancer cells, often as a primary treatment when surgery isn’t an option or isn’t desired

- Immunotherapy to trigger the body’s immune system to fight cancer cells, either in the bladder or throughout the body

- Targeted therapy to treat advanced cancer when other treatments haven’t helped.

Sometimes, the best option might include more than one of type of treatment. Surgery, alone or with other treatments, is part of the treatment for most bladder cancers. Surgery can often remove early-stage bladder tumors. But a major concern in people with early-stage bladder cancer is that new cancers often form in other parts of the bladder over time. Removing the entire bladder (known as a radical cystectomy) is one way to avoid this, but it can have major side effects. If the entire bladder is not removed, other treatments may be given to try to reduce the risk of new cancers. Whether or not other treatments are given, close follow-up is needed to look for signs of new cancers in the bladder.

Which doctors treat bladder cancer?

Depending on your options, you can have different types of doctors on your treatment team. The types of doctors who treat bladder cancers include:

- Urologists: surgeons who specialize in treating diseases of the urinary system and male reproductive system

- Radiation oncologists: doctors who treat cancer with radiation therapy

- Medical oncologists: doctors who treat cancer with medicines such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy

You might have many other specialists on your treatment team as well, including physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), nurses, psychologists, social workers, nutrition specialists, rehabilitation specialists, and other health professionals. See Health Professionals Associated With Cancer Care for more on this.

Making treatment decisions

It’s important to discuss all of your treatment options, including their goals and possible side effects, with your doctors to help make the decision that best fits your needs. Some important things to consider include:

- Your age and expected life span

- Any other serious health conditions you have

- The stage and grade of your cancer

- The likelihood that treatment will cure your cancer (or help in some other way)

- Your feelings about the possible side effects from treatment

You may feel that you must make a decision quickly, but it’s important to give yourself time to absorb the information you have just learned. It’s also very important to ask questions if there is anything you’re not sure about.

Getting a second opinion

You may also want to get a second opinion. This can give you more information and help you feel more certain about the treatment plan you choose. If you aren’t sure where to go for a second opinion, ask your doctor for help.

Thinking about taking part in a clinical trial

Clinical trials are carefully controlled research studies that are done to get a closer look at promising new treatments or procedures. Clinical trials are one way to get state-of-the art cancer treatment. In some cases, they may be the only way to get access to newer treatments. They are also the best way for doctors to learn better methods to treat cancer. Still, they are not right for everyone.

If you would like to learn more about clinical trials that might be right for you, start by asking your doctor if your clinic or hospital conducts clinical trials.

Bladder cancer surgery

Surgery is part of the treatment for most bladder cancers. The type of surgery done depends on the stage (extent) of the cancer. It also depends on your choices based on the long-term side effects of some kinds of surgery.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)

A transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) also known transurethral resection (TUR), is a procedure to diagnose bladder cancer and to remove cancers confined to the inner layers of the bladder — those that aren’t yet muscle-invasive cancers. During the TURBT procedure, a surgeon passes an electric wire loop through a cystoscope and into the bladder. The electric current in the wire is used to cut away or burn away the cancer. Alternatively, a high-energy laser may be used.

Because doctors perform the TURBT procedure through the urethra, you won’t have any cuts (incisions) in your abdomen.

As part of the TURBT procedure, your doctor may recommend a one-time injection of cancer-killing medication (chemotherapy) into your bladder to destroy any remaining cancer cells and to prevent cancer from coming back. The medication remains in your bladder for a period of time and then is drained.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) is also the most common treatment for early-stage or superficial (non-muscle invasive) bladder cancers. Most patients have superficial cancer when they are first diagnosed, so this is usually their first treatment. Some people might also get a second, more extensive TURBT as part of their treatment.

How transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) is done

This surgery is done using an instrument put up the urethra, so it doesn’t require cutting into the abdomen. You will get either general anesthesia (where you are asleep) or regional anesthesia (where the lower part of your body is numbed).

For this operation, a type of rigid cystoscope called a resectoscope is placed into the bladder through the urethra. The resectoscope has a wire loop at its end to remove any abnormal tissues or tumors. The removed tissue is sent to a lab to be looked at by a pathologist.

After the tumor is removed, more steps may be taken to try to ensure that it has been destroyed completely. Any remaining cancer may be treated by fulguration (burning the base of the tumor) while looking at it with the cystoscope. Cancer can also be destroyed using a high-energy laser through the cystoscope.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) side effects

The side effects of TURBT are generally mild and do not usually last long. You might have some bleeding and pain when you urinate after surgery. You can usually return home the same day or the next day and can resume your usual activities within a week or two.

Even if the TURBT removes the tumor completely, bladder cancer often comes back (recurs) in other parts of the bladder. This might be treated with another TURBT. But if TURBT needs to be repeated many times, the bladder can become scarred and lose its capacity to hold much urine. Some people may have side effects such as frequent urination, or even incontinence (loss of control of urination).

In patients with a long history of recurrent, non-invasive low-grade tumors, the surgeon may sometimes just use fulguration to burn small tumors that are seen during cystoscopy (rather than removing them). This can often be done using local anesthesia (numbing medicine) in the doctor’s office. It is safe but can be mildly uncomfortable.

Cystectomy

When bladder cancer is invasive, all or part of the bladder may need to be removed. This operation is called a cystectomy.

- Partial cystectomy: If the cancer has invaded the muscle layer of the bladder wall but is not very large and only in one place, it can sometimes be removed along with part of the bladder wall without taking out the whole bladder. The hole in the bladder wall is then closed. Nearby lymph nodes are also removed and examined for cancer spread. Only a small portion of people with cancer that has invaded the muscle can have this surgery. The main advantage of partial cystectomy is that the person keeps their bladder and doesn’t need reconstructive surgery (see below). But the remaining bladder may not hold as much urine, which means they will have to urinate more often. The main concern with this type of surgery is that bladder cancer can still recur in another part of the bladder wall.