What is a bone density test

A bone mineral density (BMD) test measures how much calcium and other types of minerals are in an area of your bone. The main reason to have the bone density test is to find and treat serious bone loss. Bone density test helps your health care provider detect osteoporosis and predict your risk of bone fractures. Bone mineral density uses a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. A bone-density test gives out a small amount of radiation. Most experts feel that the risk of small amount of X-ray radiation is very low compared with the benefits of finding osteoporosis before you break a bone. But the harmful effects of radiation can add up, so it is best to avoid bone density test when you can unless you have to.

By 2020, approximately 12.3 million Americans older than age 50 years are expected to have osteoporosis 1. Osteoporotic fractures, particularly hip fractures, are associated with limitation of ambulation, chronic pain and disability, loss of independence, and decreased quality of life, and 21% to 30% of patients die within 1 year of a hip fracture 2. Seventy-one percent of osteoporotic fractures occur among women 3 and women have higher rates of osteoporosis than men at any given age; however, men have a higher fracture-related mortality rate than women 4. The prevalence of primary osteoporosis (i.e., osteoporosis without underlying disease) increases with age and differs by race/ethnicity. With the aging of the U.S. population, the potential preventable burden is likely to increase in future years.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found convincing evidence that bone density tests are accurate for predicting osteoporotic fractures in women and men. Screening and treating low bone mineral density (BMD) detected through screening can result in increased bone mineral density (BMD) and decrease the risk of subsequent fractures and fracture-related morbidity and mortality. Most evidence supports screening and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women; the evidence for primary prevention in men is lacking, and future research is needed. One cannot assume that the bones of men and women are biologically the same, especially because bone density is affected by differing levels and effects of testosterone and estrogen in men and women. Moreover, rapid bone loss occurs in women due to the loss of estrogen during menopause. Although women have a higher risk of osteoporosis at an earlier age than men, likely due to loss of estrogen during menopause, it raises the question of whether the benefits of treatment observed in trials in women can be directly extrapolated to men.

The most commonly used test is central dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine. While several bone measurement tests similarly predict risk of fracture, DEXA directly measures bone mineral density (BMD), and most treatment guidelines use central DEXA to define osteoporosis and the treatment threshold to prevent osteoporotic fractures. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found adequate evidence that clinical risk assessment tools are moderately accurate in identifying risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found no studies that evaluated the effect of screening for osteoporosis on fracture rates or fracture-related morbidity or mortality.

In 2014, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommended bone density test in all women age 65 years and older and all men age 70 years and older 6. It also recommended bone density testing in postmenopausal women younger than age 65 years and men ages 50 to 69 years based on their risk factor profile, including if they had a fracture as an adult. The International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing in all women age 65 years and older and all men age 70 years and older. It also recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing in postmenopausal women younger than age 65 years and men younger than age 70 years who have risk factors for low bone mass 7. The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends screening in women age 65 years and older and younger women whose fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman 8. In 2012 (and reaffirmed in 2014) the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended bone density screening with DXA beginning at age 65 years in all women and selective screening in postmenopausal women younger than age 65 years who have osteoporosis risk factors or an adult fracture 9. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists also recommends evaluating all women age 50 years and older for osteoporosis risk and consider bone density testing based on clinical fracture risk profile 10. The Endocrine Society recommends screening in men older than age 70 years and adults ages 50 to 69 years with significant risk factors or fracture after age 50 years 11.

Bone mineral density (BMD) tests are used to:

- Diagnose bone loss and osteoporosis

- See how well osteoporosis medicine is working

- Predict your risk of future bone fractures

You should have bone mineral testing or screening if you have an increased risk of osteoporosis.

You are more likely to get osteoporosis if you are:

- A woman, age 65 or older

- A man, age 70 or older

Women under age 65 and men ages 50 to 70 are at increased risk of osteoporosis if they:

- Have a broken bone caused by normal activities, such as a fall from standing height or lower (fragility fracture)

- Have rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, or eating disorders

- Have early menopause (either from natural causes or surgery)

- History of hormone treatment for prostate cancer or breast cancer

- Have had a significant loss of height due to compression fractures of the back

- Smoke

- Have a strong family history of osteoporosis

- Take corticosteroid medicines (prednisone or methylprednisolone) every day for more than 3 months

- Take thyroid hormone replacement

- Have three or more drinks of alcohol a day on most days

Regardless of your sex or age, your doctor may recommend a bone density test if you’ve:

- Lost height. People who have lost at least 1.6 inches (4 centimeters) in height may have compression fractures in their spines, for which osteoporosis is one of the main causes.

- Fractured a bone. Fragility fractures occur when a bone becomes so fragile that it breaks much more easily than expected. Fragility fractures can sometimes be caused by a strong cough or sneeze.

- Taken certain drugs. Long-term use of steroid medications, such as prednisone, interferes with the bone-rebuilding process — which can lead to osteoporosis.

- Received a transplant. People who have received an organ or bone marrow transplant are at higher risk of osteoporosis, partly because anti-rejection drugs also interfere with the bone-rebuilding process.

- Had a drop in hormone levels. In addition to the natural drop in hormones that occurs after menopause, women’s estrogen may also drop during certain cancer treatments. Some treatments for prostate cancer reduce testosterone levels in men. Lowered sex hormone levels weaken bone.

Current practice recommends bone density retesting every 2 years. However, some women may be able to wait a much longer time between their screening bone density tests. Talk to your provider about how often you should be tested.

How much does a bone density test cost?

A DEXA scan costs about $125. Not all health insurance plans pay for bone density tests, so ask your insurance provider beforehand if you’re covered.

How long does a bone density test take?

The bone density test usually takes about 10 to 30 minutes.

How often should I get bone density scan screening test?

The potential value of rescreening women whose initial screening test did not detect osteoporosis is to improve fracture risk prediction. A lack of evidence exists about optimal intervals for repeated screening and whether repeated screening is necessary in a woman with normal bone mineral density (BMD). Because of limitations in the precision of testing, a minimum of two years may be needed to reliably measure a change in bone mineral density (BMD); however, longer intervals may be necessary to improve fracture risk prediction. A prospective study of 4,124 women 65 years or older found that neither repeated bone mineral density (BMD) measurement nor the change in bone mineral density (BMD) after eight years was more predictive of subsequent fracture risk than the original measurement 12.

Potential harms of bone density scan screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found no studies that directly examined harms of screening in men. Potential harms of screening in men are likely to be similar to those in women. Evidence on treatment harms in men is very limited 4.

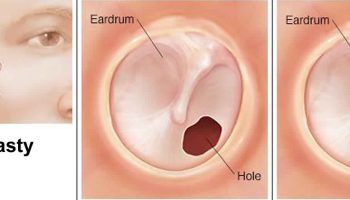

Figure 1. Bone density – with bone loss, the outer shell of a bone becomes thinner and the interior becomes more porous. Normal bone (A) is strong and flexible. Osteoporotic bone (B) is weaker and subject to fracture.

Low Bone Mass Versus Osteoporosis

The information provided by a bone mineral density (BMD) test can help your doctor decide which prevention or treatment options are right for you.

If you have low bone mass that is not low enough to be diagnosed as osteoporosis, this is sometimes referred to as osteopenia. Low bone mass can be caused by many factors such as:

- heredity

- the development of less-than-optimal peak bone mass in your youth

- a medical condition or medication to treat such a condition that negatively affects bone

- abnormally accelerated bone loss.

Although not everyone who has low bone mass will develop osteoporosis, everyone with low bone mass is at higher risk for the disease and the resulting fractures.

As a person with low bone mass, you can take steps to help slow down your bone loss and prevent osteoporosis in your future. Your doctor will want you to develop—or keep—healthy habits such as eating foods rich in calcium and vitamin D and doing weight-bearing exercise such as walking, jogging, or dancing. In some cases, your doctor may recommend medication to prevent osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis: If you are diagnosed with osteoporosis, these healthy habits will help, but your doctor will probably also recommend that you take medication. Several effective medications are available to slow—or even reverse—bone loss. If you do take medication to treat osteoporosis, your doctor can advise you concerning the need for future bone mineral density (BMD) tests to check your progress.

Who should get a bone density test ?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 recommends that all women over age 65 should have a bone density test. Women who are younger than age 65 and at high risk for fractures should also have a bone density test (asymptomatic screening). Men age 70 and up may want to talk with their doctors about the risks and benefits before deciding on bone density test for asymptomatic screening.

You may need a follow-up bone-density test after several years. That depends on the results of your first test. Younger women, and men ages 50 to 69, should consider the bone density test if they have risk factors for serious bone loss.

Risk factors for osteoporosis include:

- Breaking a bone in a minor accident.

- Having rheumatoid arthritis.

- Having a parent who broke a hip.

- Smoking

- Drinking heavily.

- Having a low body weight.

- Using corticosteroid drugs for three months or more.

- Having a very low vitamin D level.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation – Screening Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures 5

- Women age 65 years and older: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing to prevent osteoporotic fractures in women age 65 years and older.

- Postmenopausal women younger than age 65 years at increased risk of osteoporosis: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for osteoporosis with bone measurement testing in postmenopausal women younger than age 65 years who are at increased risk of osteoporosis, as determined by a formal clinical risk assessment tool.

- Men: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis to prevent osteoporotic fractures in men.

The drugs used to treat bone loss

The most common drugs to treat bone loss are Fosamax (generic alendronate), Boniva (generic ibandronate), and Actonel (generic risendronate).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found convincing evidence that drug therapies reduce subsequent fracture rates in postmenopausal women. The benefit of treating screening-detected osteoporosis is at least moderate in women age 65 years and older and younger postmenopausal women who have similar fracture risk. The harms of treatment range from no greater than small for bisphosphonates and parathyroid hormone to small to moderate for raloxifene and estrogen. Therefore, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 concludes with moderate certainty that the net benefit of screening for osteoporosis in these groups of women is at least moderate.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 concludes that the evidence is inadequate to assess the effectiveness of drug therapies in reducing subsequent fracture rates in men without previous fractures. Treatments that have been proven effective in women cannot necessarily be presumed to have similar effectiveness in men, and the direct evidence is too limited to draw definitive conclusions. Thus, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 could not assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis in men.

1) Women younger than age 65 years who have additional risk for osteoporosis, based on medical history and other findings. Additional risk factors for osteoporosis include:

- Estrogen deficiency.

- A history of maternal hip fracture that occurred after the age of 50 years.

- Low body mass (less than 127 lbs or 57.6 kg).

- History of amenorrhea (more than 1 year before age 42 years).

2) Women younger than age 65 years or men younger than age 70 years who have additional risk factors, including:

- Current use of cigarettes

- Loss of height, thoracic kyphosis.

3) Individuals of any age with bone mass osteopenia, or fragility fractures on imaging studies such as radiographs, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

4) Individuals age 50 years and older who develop a wrist, hip, spine, or proximal humerus fracture with minimal or no trauma, excluding pathologic fractures.

5) Individuals of any age who develop 1 or more insufficiency fractures.

6) Individuals receiving (or expected to receive) glucocorticoid therapy for more than 3 months.

7) Individuals beginning or receiving long-term therapy with medications known to adversely affect bone mineral density (BMD) (e.g., anticonvulsant drugs, androgen deprivation therapy, aromatase inhibitor therapy, or chronic heparin).

8) Individuals with an endocrine disorder known to adversely affect bone mineral density (BMD) (e.g., hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, or Cushing’s syndrome).

9) Hypogonadal men older than 18 years and men with surgically or chemotherapeutically induced castration.

10) Individuals with medical conditions that could alter bone mineral density (BMD), such as:

- Chronic renal failure.

- Rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritis.

- Eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

- Organ transplantation.

- Prolonged immobilization.

- Conditions associated with secondary osteoporosis, such as gastrointestinal malabsorption or malnutrition, sprue, osteomalacia, vitamin D deficiency, endometriosis, acromegaly, chronic alcoholism or established cirrhosis, and multiple myeloma.

- Individuals who have had gastric bypass for obesity. The accuracy of DEXA in these patients might be affected by obesity.

11) Individuals being considered for pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis.

12) Individuals being monitored to:

- Assess the effectiveness of osteoporosis drug therapy 13.

- Follow-up medical conditions associated with abnormal bone mineral density (BMD).

13) Children or adolescents with medical conditions associated with abnormal bone mineral density (BMD) 14 including but not limited to:

- Individuals receiving (or expected to receive) glucocorticoid therapy for more than 3 months.

- Individuals receiving radiation or chemotherapy for malignancies.

- Individuals with an endocrine disorder known to adversely affect bone mineral density (BMD) (e.g., hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, growth hormone deficiency or Cushing’s syndrome).

- Individuals with bone dysplasias known to have excessive fracture risk (osteogenesis imperfecta, osteopetrosis) or high bone density.

- Individuals with medical conditions that could alter bone mineral density (BMD), such as:

- Chronic renal failure.

- Rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritis.

- Eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

- Organ transplantation.

- Prolonged immobilization.

- Conditions associated with secondary osteoporosis, such as gastrointestinal malabsorption, sprue, inflammatory bowel disease, malnutrition, osteomalacia, vitamin D deficiency, acromegaly, cirrhosis, HIV infection, prolonged exposure to fluorides.

14) DEXA scan may be indicated in the diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of individuals with conditions that result in pathologically increased bone mineral density (BMD), such as osteopetrosis or prolonged exposure to fluoride.

15) DEXA scan may be indicated as a tool to measure regional and whole body fat and lean mass (e.g., for patients with malabsorption, cancer, or eating disorders) 15.

Who shouldn’t get a bone density test ?

Most men, and women under age 65, probably don’t need the bone density scan test.

Most people do not have serious bone loss.

Most people have no bone loss or have mild bone loss (called osteopenia). Their risk of breaking a bone is low. They do not need the test. They should exercise regularly and get plenty of calcium and vitamin D. This is the best way to prevent bone loss.

The bone scan has risks.

A bone-density test gives out a small amount of radiation. But the harmful effects of radiation can add up, so it is best to avoid it when you can.

The treatments have limited benefits.

Many people are given drugs because they have mild bone loss. But, there is little evidence that these drugs help them.

And, even if the drugs do help, they may only help for a few years. So, you may want to consider them only if you have serious bone loss. Serious bone loss is called osteoporosis.

Bone density test may be of limited value or require modification of the technique or rescheduling of the examination in some situations, including:

- Recently administered gastrointestinal contrast or radionuclides.

- Pregnancy.

- Severe degenerative changes or fracture deformity in the measurement area.

- Implants, hardware, devices, or other foreign material in the measurement area.

- The patient’s inability to attain correct position and/or remain motionless for the measurement.

- Extremes of high or low body mass index (BMI) which may adversely affect the ability to obtain accurate and precise measurements. Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) may be a desirable alternative in these individuals 16.

- Any condition that precludes proper positioning of the patient to be able to obtain accurate bone mineral density (BMD) values.

How is a bone density test done

Bone density testing can be done in several ways.

The most common and accurate way uses a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. DEXA uses low-dose x-rays. (You receive more radiation with a chest x-ray.) The scan is painless. You need to remain still during the test.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is a clinically proven method of measuring bone mineral density (BMD) in the lumbar spine, proximal femur, forearm, and whole body 17. It is used primarily in the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis and other disease states characterized by abnormal bone mineral density (BMD), as well as to monitor response to therapy for these conditions 18. It may also be used to measure whole-body composition 19.

There are two types of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans:

- Central DEXA. You lie on a soft table. The scanner passes over your lower spine and hip. In most cases, you do not need to undress. This scan is the best test to predict your risk of fractures, especially of the hip.

- Peripheral DEXA (p-DEXA). These smaller machines measure the bone density in your wrist, fingers, leg, or heel. These machines are in health care offices, pharmacies, shopping centers, and at health fairs.

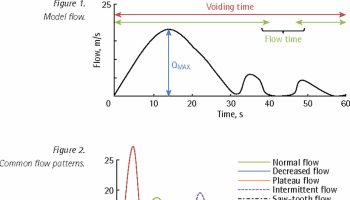

Figure 2. Bone density testing

Figure 3. Bone density test locations – bone density tests are usually done on bones in the spine (vertebrae), hip, forearm, wrist, fingers and heel.

Central dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) for osteoporosis diagnosis

- The World Health Organization (WHO) international reference standard for osteoporosis diagnosis is a T-score of -2.5 or less at the femoral neck.

- The reference standard from which the T-score is calculated is the female, white, age 20-29 years, NHANES III database

- Osteoporosis may be diagnosed in postmenopausal women and in men age 50 and older if the T-score of the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck is -2.5 or less:

- In certain circumstances the 33% radius (also called 1/3 radius) may be utilized.

The T-Score

Most commonly, your bone mineral density (BMD) test results are compared to the ideal or peak bone mineral density of a healthy 30-year-old adult, and you are given a T-score. A score of 0 means your bone mineral density (BMD) is equal to the norm for a healthy young adult. Differences between your bone mineral density (BMD) and that of the healthy young adult norm are measured in units called standard deviations (SDs). The more standard deviations below 0, indicated as negative numbers, the lower your bone mineral density (BMD) and the higher your risk of fracture.

As shown in the table below, a T-score between +1 and −1 is considered normal or healthy. A T-score between −1 and −2.5 indicates that you have low bone mass, although not low enough to be diagnosed with osteoporosis. A T-score of −2.5 or lower indicates that you have osteoporosis. The greater the negative number, the more severe the osteoporosis.

Table 1. T-score and bone mineral density (BMD) test

| Level | Definition |

|---|---|

| Normal | Bone density is within 1 SD (+1 or −1) of the young adult mean. |

| Low bone mass | Bone density is between 1 and 2.5 SD below the young adult mean (T-score of −1 to −2.5 SD). |

| Osteoporosis | Bone density is 2.5 SD or more below the young adult mean (T-score of −2.5 SD or lower). |

| Severe (established) osteoporosis | Bone density is more than 2.5 SD below the young adult mean, and there have been one or more osteoporotic fractures. |

Bone density test procedure

How you prepare

Bone density tests are easy, fast and painless. Virtually no preparation is needed. In fact, some simple versions of bone density tests can be done at your local pharmacy or drugstore.

- If you are or could be pregnant, tell your provider before bone density test is done.

- If you’re having the test done at a medical center or hospital, be sure to tell your doctor beforehand if you’ve recently had a barium exam or had contrast material injected for a CT scan or nuclear medicine test. Contrast materials might interfere with your bone density test.

Food and medications

DO NOT take calcium supplements for at least 24 hours before your bone density test.

Clothing and personal items

Wear loose, comfortable clothing and avoid wearing clothes with zippers, belts or buttons. Remove all metal objects from your pockets, such as keys, money clips or change.

What you can expect during a bone density test

Bone density tests are usually done on bones that are most likely to break because of osteoporosis, including:

- Lower spine bones (lumbar vertebrae)

- The narrow neck of your thighbone (femur), next to your hip joint

- Bones in your forearm

If you have your bone density test done at a hospital, it’ll probably be done on a central device, where you lie on a padded platform while a mechanical arm passes over your body. The amount of radiation you’re exposed to is very low, much less than the amount emitted during a chest X-ray. The test usually takes about 10 to 30 minutes.

A small, portable machine can measure bone density in the bones at the far ends of your skeleton, such as those in your finger, wrist or heel. The instruments used for these tests are called peripheral devices, and are often found in pharmacies. Tests of peripheral bone density are less expensive than are tests done on central devices.

Because bone density can vary from one location in your body to another, a measurement taken at your heel usually isn’t as accurate a predictor of fracture risk as a measurement taken at your spine or hip. Consequently, if your test on a peripheral device is positive, your doctor might recommend a follow-up scan at your spine or hip to confirm your diagnosis.

Bone density test results

Normal bone density test results

The results of your bone density test are usually reported as a T-score and Z-score:

- T-score compares your bone density with that of a healthy young women.

- Z-score compares your bone density with that of other people of your age, gender, and race. Z-scores should be population specific where adequate reference data exist. For the purpose of Z-score calculation, the patient’s self-reported ethnicity should be used.

With either score, a negative number means you have thinner bones than average. The more negative the number, the higher your risk of a bone fracture.

A T-score is within the normal range if it is -1.0 or above.

Abnormal bone density test results

Bone mineral density testing does not diagnose fractures. Along with other risk factors you may have, it helps predict your risk of having a bone fracture in the future. Your provider will help you understand the results.

If your T-score is:

- Between -1 and -2.5, you may have early bone loss (osteopenia).

- Below -2.5, you likely have osteoporosis.

Treatment recommendation depends on your total fracture risk. This risk can be calculated using the FRAX score. Your provider can tell you more about this.

Potential harms of screening and treatment

Potential harms of screening for osteoporosis include false-positive test results, which can lead to unnecessary treatment; false-negative test results; and patient anxiety about positive test results. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found no studies that addressed the potential harms of screening. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 did review several studies that reported on harms of various medications. Overall, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 determined the potential harms of pharmacotherapy to be small.

Bisphosphonates

Similar to the evidence on the benefits of pharmacotherapy for the primary prevention of fractures, the most available evidence on the harms of pharmacotherapy is for bisphosphonates. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 identified 16 studies on alendronate, five studies on zoledronic acid, six studies on risedronate, two studies on etidronate, and seven studies on ibandronate that reported on harms. Overall, based on pooled analyses, studies on bisphosphonates showed no increased risk of discontinuation, serious adverse events or upper gastrointestinal events 4. Evidence on bisphosphonates and cardiovascular events is more limited and generally shows no significant difference or nonsignificant increases in atrial fibrillation with bisphosphonate therapy. Concerns have been raised about osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical fractures of the femur with bisphosphonate therapy. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found only three studies that reported on osteonecrosis of the jaw, and none of these studies found any cases 4. The previous review noted a case series published by the FDA that reported on osteonecrosis of the jaw with bisphosphonate use in cancer patients. A more recent systematic review that did not meet inclusion criteria (because it included populations with a previous fracture) found higher incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw with intravenous bisphosphonate use and with greater duration of use. No studies that met inclusion criteria for the current review reported on atypical fractures of the femur, although some studies and systematic reviews that did not meet inclusion criteria (because of wrong study population, study design, or intervention comparator) reported an increase in atypical femur fractures with bisphosphonate use. Three trials that reported on harms of bisphosphonates included men (either combining results for men and women or including men only); results were consistent with those of women for risk of discontinuation, serious adverse events, and upper gastrointestinal events.

Raloxifene

Six trials of raloxifene therapy in women reported on various harms. Pooled analyses showed no increased risk of discontinuation due to adverse events or increased risk of leg cramping 4. However, analyses found a nonsignificant trend for increased risk of deep vein thrombosis, as well as an increased risk of hot flashes 4. The previous review found an increased risk of thromboembolic events with raloxifene 4.

Denosumab

Three studies (n=8,451) reported on harms of denosumab therapy in postmenopausal women. Pooled analyses showed no significant increase in discontinuation or serious adverse events but found a nonsignificant increase in serious infections 4. All three studies reported higher infection rates in women taking denosumab, and further analysis found a higher rate of cellulitis and erysipelas 4.

Parathyroid Hormone

A single study of parathyroid hormone therapy in women (n=2,532) reported a higher risk of discontinuation and other adverse events, such as nausea and headache 4, while a single, smaller study in men found no increased risk of discontinuation or cancer 4 using the FDA-approved dose of 20 μg per day (n=298) 20.

Estrogen

Similar to the evidence on the benefits of estrogen for the primary prevention of fractures, no studies met inclusion criteria for the current review. However, based on findings from the Women’s Health Initiative trial, the previous review found a higher rate of gallbladder events, stroke, and venous thromboembolism with estrogen therapy, and an increased risk of urinary incontinence during 1 year of followup 4. Women taking combined estrogen and progestin had a higher risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, probable dementia, gallbladder events, stroke, and venous thromboembolism compared with women taking placebo, and an increased risk of urinary incontinence during 1 year of followup 4.

Effectiveness of early detection and treatment

No controlled studies have evaluated the effect of screening for osteoporosis on fracture rates or fracture-related morbidity or mortality in either women or men. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 reviewed the evidence on drug therapies for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fractures. The vast majority of studies were conducted in women exclusively; only two studies were conducted in men 4. Overall, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 found that pharmacotherapy is effective in treating osteoporosis and reducing fractures in postmenopausal women.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates were studied most frequently; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 identified seven studies on alendronate, two trials on zoledronic acid, four trials on risedronate, and two trials on etidronate. All but one study were conducted in postmenopausal women. For women, bisphosphonates were found to significantly reduce vertebral fractures and nonvertebral fractures but not hip fractures 4. In the single study of men (n=1,199), zoledronic acid was found to reduce morphometric vertebral fractures but not nonvertebral fractures 4.

Raloxifene

Only one study (n=7,705) on raloxifene met inclusion criteria for the review. It evaluated raloxifene in postmenopausal women and reported a reduction in vertebral fractures but not nonvertebral fractures 4.

Denosumab

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 identified three studies that evaluated denosumab; however, only one study was adequately powered to assess fractures. This study (n=7,868) evaluated denosumab in women and found a significant reduction in vertebral fractures, nonvertebral fractures and hip fractures 4.

Parathyroid Hormone

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 reviewed evidence from two trials on parathyroid hormone. One trial (n=2,532) was conducted in women and reported a significant reduction in vertebral fractures but not nonvertebral fractures 4. The other trial was conducted in men and reported a nonsignificant reduction in nonvertebral fractures when comparing the FDA-approved dose of 20 μg per day vs. placebo (n=298) 20. However, the number of fractures in the study was small and the study was stopped early due to concerns about osteosarcoma found in animal studies.

Estrogen

Although the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation 5 did not identify any studies on estrogen for the primary prevention of fractures that met inclusion criteria, the previous review found that estrogen reduces vertebral fractures based on data from the Women’s Health Initiative trial.

References- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520-6.

- Brauer CA, Coca-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1573-9.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, et al. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):465-75.

- Viswanathan M, Reddy S, Berkman N, et al. Screening to Prevent Osteoporotic Fractures: An Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis No. 162. AHRQ Publication No. 15-05226-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

- Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement/osteoporosis-screening1

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2014;25(10):2359-81.

- The International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2015 ISCD Official Positions—Adult. 2015. http://www.iscd.org/official-positions/2015-iscd-official-positions-adult/

- Screening for Osteoporosis: Recommendation Statement. Am Fam Physician. 2011 May 15;83(10):1197-1200. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0515/p1197.html

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 129. Osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):718-34.

- Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis-2016–executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(9):1111-8.

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al; Endocrine Society. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clinc Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1802-22.

- Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, et al. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):155–160.

- Bonnick SL, Shulman L. Monitoring osteoporosis therapy: bone mineral density, bone turnover markers, or both? Am J Med 2006;119:S25-31.

- Bachrach LK. Osteoporosis and measurement of bone mass in children and adolescents. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2005;34:521-535, vii.

- Wong WW, Hergenroeder AC, Stuff JE, Butte NF, Smith EO, Ellis KJ. Evaluating body fat in girls and female adolescents: advantages and disadvantages of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:384-389.

- Yu DS, Lee DT. Do medically unexplained somatic symptoms predict depression in older Chinese? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:119-126.

- Baim S, Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, et al. Official Positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom 2008;11:75-91.

- Cummings SR, Bates D, Black DM. Clinical use of bone densitometry: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:1889-1897.

- Wells JC, Haroun D, Williams JE, et al. Evaluation of DXA against the four-component model of body composition in obese children and adolescents aged 5-21 years. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:649-655.

- Orwoll ES, Scheele WH, Paul S, et al. The effect of teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1-34)] therapy on bone density in men with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(1):9-17.