Bouveret syndrome

Bouveret syndrome also known as Bouveret’s syndrome, is a very rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction that is caused by a large gallstone passing through a cholecystoduodenal, cholecystogastric or rarely a choledochoduodenal fistula 1, 2. Bouveret syndrome is an infrequent form of gallstone ileus arises from the impaction of a large gallstone in the proximal duodenum or pylorus secondary to a spontaneous fistula between the gallbladder and the duodenum or stomach. Bouveret syndrome is estimated to occur in approximately 1% to 3% of all of the patients with gallstone related obstructions in the gastrointestinal tract and represents the rarest of all forms of gallstone ileus 3. Only 315 cases have been reported since it was first described by the French physician Leon Bouveret in 1896 4, 5. This can be explained by the fact that only 0.3 to 5% of gallstones develop fistulas, and that most stones are relatively small and pass either uneventfully or with terminal ileum impaction 4. Although rare, Bouveret syndrome represents a syndrome with an alarmingly high mortality rate, which is estimated between 12% and 30% 2. The prevalence of Bouveret syndrome is highest in elderly White women, with a mean age of presentation being 74 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1.9 4. Thus, it has disproportionately high rates of morbidity and mortality. Whereas Bouveret syndrome is sometimes treated endoscopically, surgical treatment modalities are pursued in 91% of cases 4. As a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, Bouveret syndrome remains poorly understood and is often misdiagnosed 6.

Bouveret’s syndrome usually presents with non-specific symptoms, most commonly a triad of epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting 4. Bouveret’s syndrome could also present with abdominal pain, distension, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, fever, weight loss, and anorexia. Physical exam usually shows abdominal tenderness, distension, and dehydration.

The Rigler’s triad of gastric outlet obstruction, ectopic gallstone and pneumobilia on radiological imaging is pathognomonic for Bouveret syndrome 7, 8, 9, which unfortunately are not always present, making it a challenging diagnosis 10. Pneumobilia also known as aerobilia, is the accumulation of gas in the biliary tree. Bouveret’s syndrome diagnosis can be established on CT, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreato-graphy (MRCP), ultrasound or upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy. CT is usually the most practical—its sensitivity for Rigler’s triad is between 75 and 78% 11, 12. Prognosis can be improved by early utilization of imaging modalities to identify the Rigler triad, which is present in over one third of cases and having a high clinical suspicion leading to prompt endoscopic or surgical intervention 13. In addition, for older patients in whom cholecystectomy might not be an option, medical management with ursodiol for prophylaxis against future gallstones may be prudent.

Bouveret syndrome can be broadly categorized into surgical and minimally invasive modalities 5. Surgical treatment involves gastric or enteric lithotomy via laparoscopy or laparotomy, with or without repair of cholecystoduodenal or choledochoduodenal fistula and cholecystectomy. Surgery has substantially higher success rates compared to the minimally invasive options—up to 90% for gastric or enteric lithotomy alone, and up to 82% if also including fistula repair and cholecystectomy 14. Surgery can be performed as a single operation or as two operations with a staged procedure for fistula repair and cholecystectomy. The option of single operation has higher incidences of post-operative complications, but it has lower rates of recurrent retrograde biliary sepsis and gallstone ileus 5. The single- versus two-operation decision is made based on the degree of patient frailty, clinical illness severity and surgical complexity 15. Because many of the affected patients are elderly and have comorbid conditions, mortality is high and surgery is risky 16. In such patients, cholecystectomy with concomitant fistula repair may therefore be contraindicated 15. However, if the fistula is not repaired, the risk for recurrent gallstone ileus and gallstone pancreatitis remains high (6). Furthermore, patients with cholecystoenteric fistulas are at higher risk for carcinomas of the gallbladder 15. For this reason, cholecystectomy is most beneficial in young patients to decrease the likelihood of future malignancy.

Minimally invasive treatment includes endoscopic retrieval as well as laser, mechanical, electrohydraulic or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy 5. Although these options are associated with much lower complication rates, but their success rates are typically around 10 to 25% 14. Lithotripsy can cause migration of fragments along the gastrointestinal tract and result in distal obstruction 13. Nevertheless, these options provide useful alternatives when patients cannot have surgery 5. As more endoscopy-based treatment options have become available with continued progress and refinement of endoscopic techniques over the last two decades. This improvement is reflected in rising success rates for the treatment of Bouveret’s syndrome from 13.6% – 18.0% to 43.0% 17.

Figure 1. Gallbladder anatomy

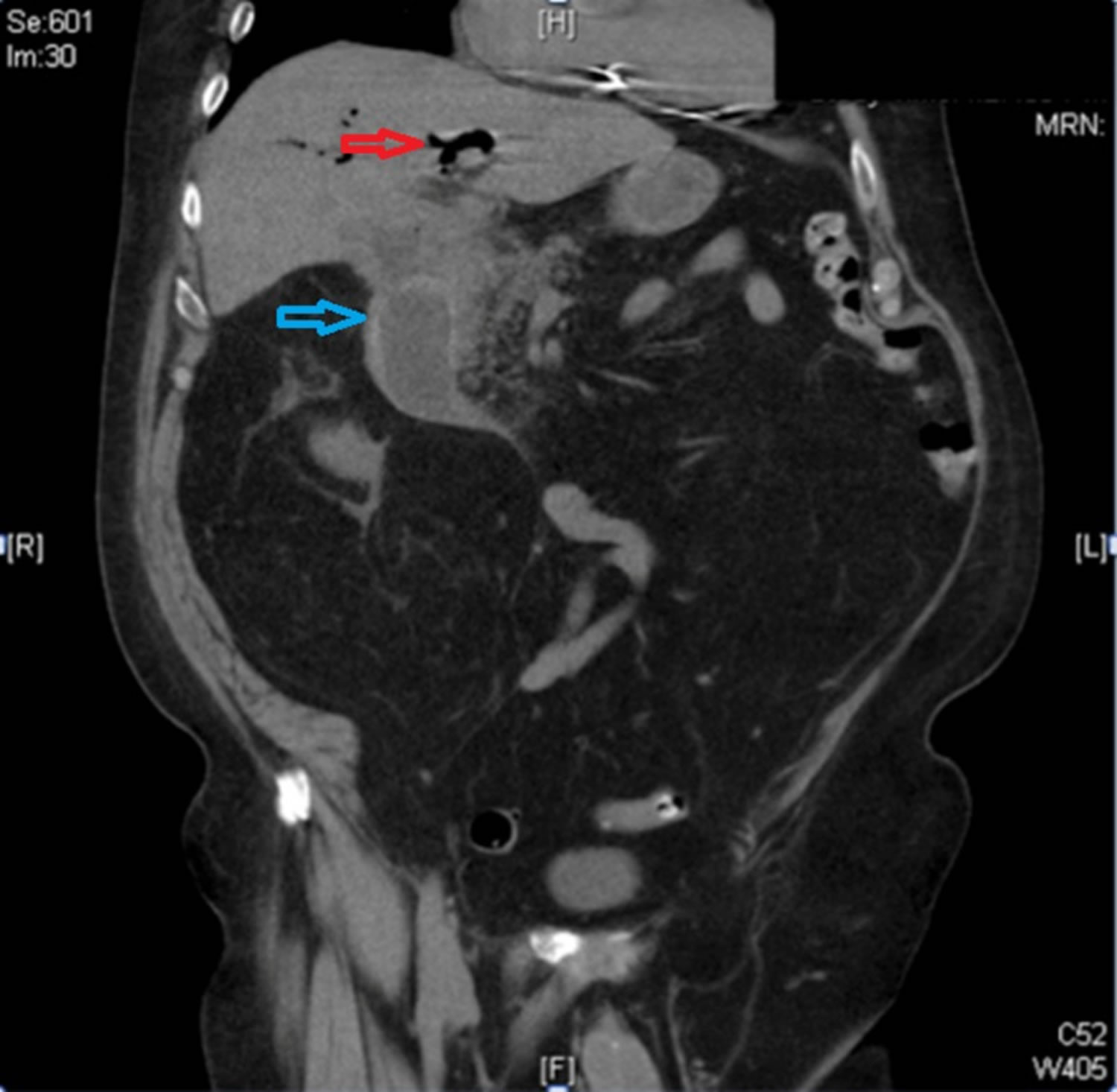

Figure 2. Bouveret syndrome

Footnote: Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showing impacted gallstone in the duodenum (blue arrow) and pneumobilia (red arrow)

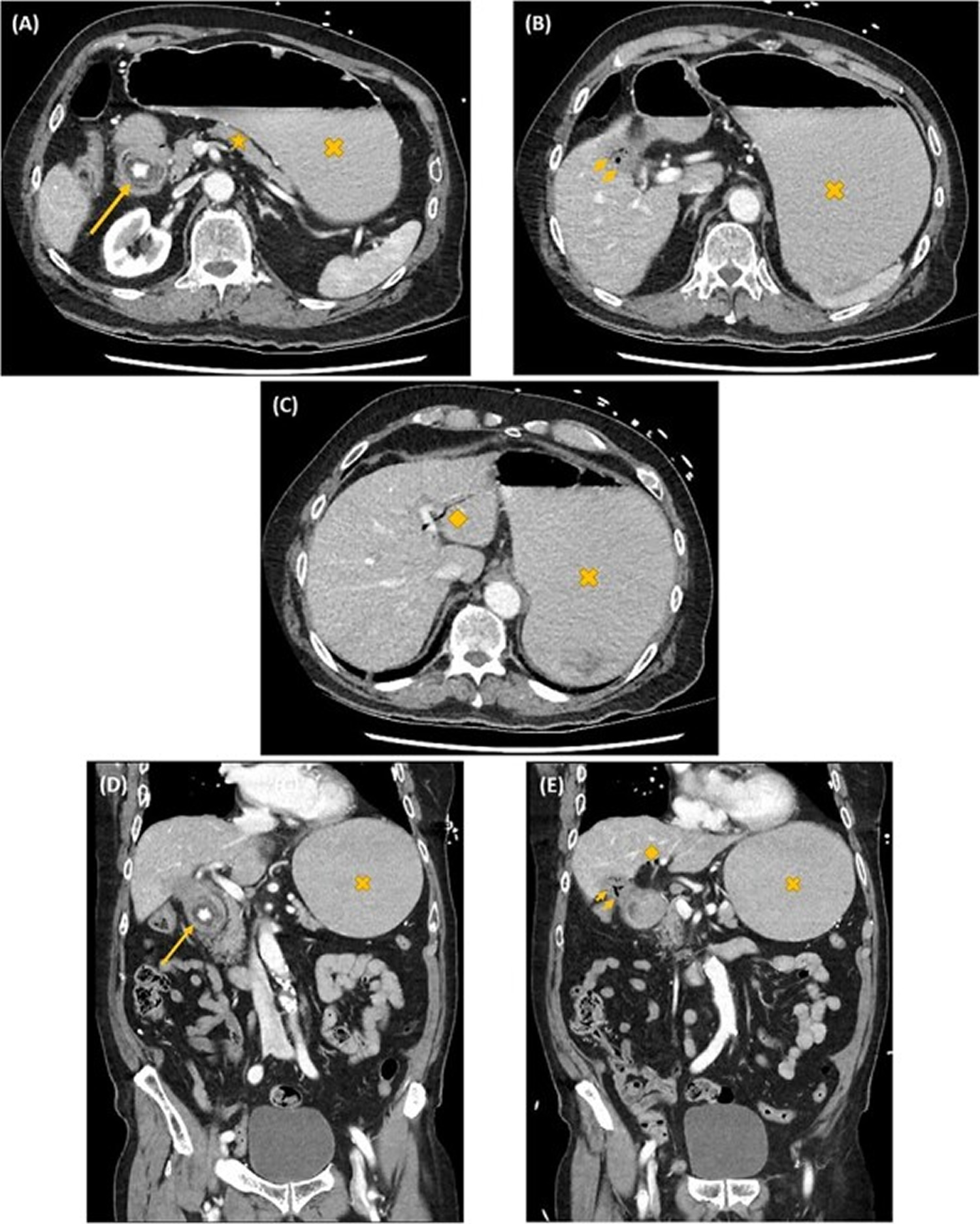

[Source 6 ]Figure 3. Rigler’s triad

Footnote: The Rigler’s triad. Axial (A–C) and coronal (D, E) computed tomography images showing gastric outlet obstruction (cross) due to a 3 cm hyperdense ectopic gallstone between the first and second parts of duodenum (arrow), with intrahepatic pneumobilia (diamond) and a decompressed gallbladder (arrow heads).

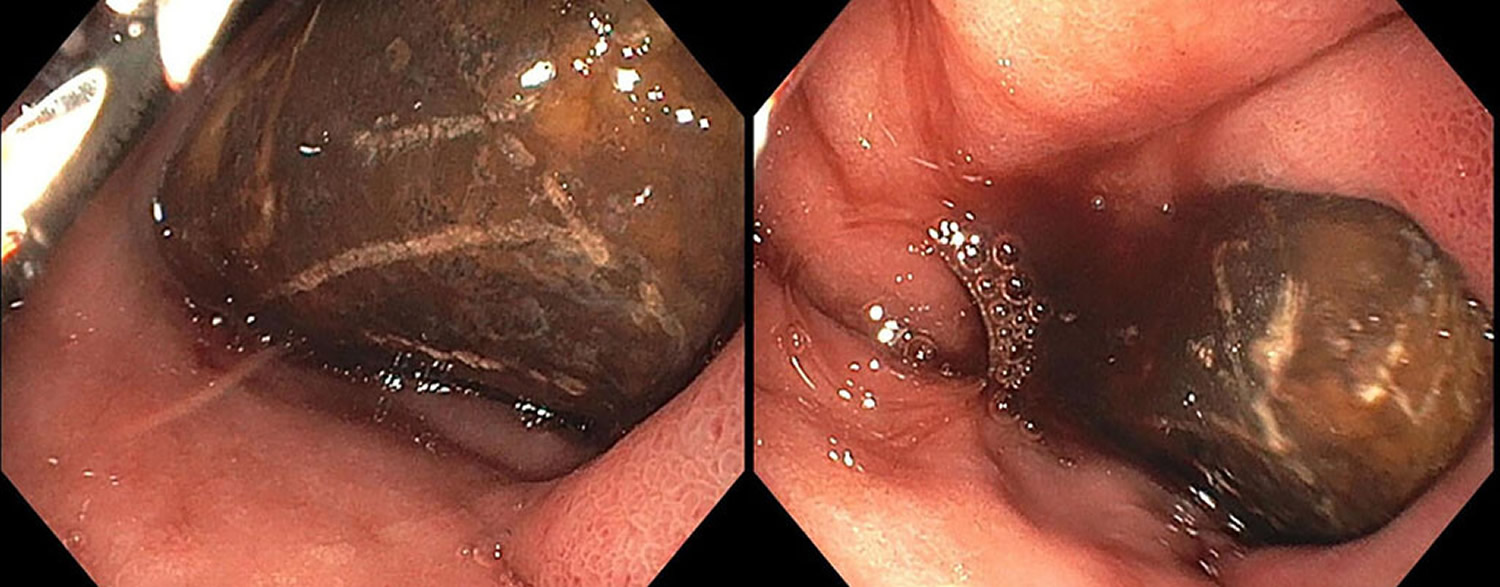

[Source 5 ]Figure 4. Bouveret’s syndrome showing obstruction secondary to an affected gallstone in the distal duodenum

Footnote: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showing obstruction secondary to an affected gallstone in the distal duodenum. Blood is seen around the stone, likely from ulceration due to impaction.

[Source 16 ]Bouveret’s syndrome symptoms

Bouveret’s syndrome usually presents with non-specific symptoms, most commonly a triad of epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting 4. Bouveret’s syndrome could also present with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, fever, weight loss, and anorexia. The patient may also exhibit right hypochondrium pain and signs of dehydration and weight loss 2. Less frequently, Bouveret syndrome may present with hematemesis (vomiting blood) secondary to duodenal and celiac artery erosions or the expulsion of gallstones in the vomitus. Usually, the symptoms begin 5 to 7 days before patients seek medical consultation. Notably, the intensity of the pain often does not correlate with the underlying anatomic alteration.

The highest prevalence of Bouveret syndrome is among frail elderly women, with a median age of 74 years and a female-to-male ratio of 1.9 18.

Bouveret syndrome complications

The complications of untreated Bouveret syndrome include ongoing gastric outlet obstruction resulting in anorexia, dehydration, nutritional deficiencies, and electrolyte abnormalities. The most feared complication is intestinal perforation which can lead to major morbidities.

Specific complications are related to the mode of treatment strategy employed. Incomplete lithotripsy may lead to recurrent gallstone ileus. Shock wave dispersion may lead to damage to surrounding structures. If a fistula is not excised, there is a risk of recurrent Bouveret syndrome, biliary sepsis, gallstone pancreatitis, and theoretical cancer risk. Surgery in itself carries the inherent risks of bleeding and infection. In addition, cholecystectomy may result in inadvertent injury to the biliary tree, especially in the presence of inflammation 19.

Bouveret syndrome causes

Bouveret syndrome is a very rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction that is caused by a large gallstone impaction at the pylorus or proximal duodenum 9, 13. The gallstone entry point is typically via a bilioenteric fistula between the gallbladder and a portion of the stomach or intestine 20, which develops from chronic inflammation and pressure necrosis 9. Cholecystoduodenal fistula is the most common form of bilioenteric fistula, as seen in about 60% of cases 11. Less common variants, choledochoduodenal account for 17% and cholecystogastric fistula account for about 5% of cases 11. Cholecystogastric fistula is probably the rarest because of the thickness of the gastric wall 21. However, most ectopic gallstones pass through defecation or vomiting, even with a bilioenteric fistula. Clinically symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction are likely to arise with larger gallstones in addition to other factors like pre-existing stenosis or post-surgical altered anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract 11.

Following an attack of acute cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder), the resulting inflammation and adhesion of the gallbladder to gastrointestinal tract, together with mechanical pressure applied by gallstones on the gallbladder itself and bowel wall, may result in an ischemic tear of the apposed gallbladder and enteric wall; this mechanism potentiates a fistula between the gallbladder and bowel where the gallstone could pass 22. Apart from acute cholecystitis, a few case reports have been published of the development of a cholecystoenteric fistula consequent to a gallbladder malignancy 23, 24.

Risk factors for Bouveret syndrome

Risk factors for Bouveret syndrome are 25, 2:

- Old age (>60 years)

- Female gender

- Large gallstones >2 cm

- Recurrent biliary colic and chronic cholecystitis

- Post-surgical altered gastrointestinal anatomy

The well-studied risk factors for Bouveret syndrome include a history of gallstones (cholelithiasis), stones greater than 2 cm to 8 cm, female gender, and age older than 60 years. It has been reported that approximately 43% to 68% of patients have a history of recurrent biliary colic, jaundice, or acute cholecystitis 26.

Bouveret syndrome diagnosis

Early diagnosis is important because mortality is high, with reported figures ranging between 12% and 30% 2. Physical exam is non-specific and usually shows abdominal tenderness, abdominal distension, dehydration or dry mucous membranes, high-pitched bowel sounds, and obstructive jaundice 14.

Unfortunately, laboratory studies are also typically non-specific. Laboratory studies may show jaundice and hepatic enzyme alterations, but this is only seen in about one-third of the patients with Bouveret syndrome 2. Leucocytosis, electrolyte abnormalities, acid-base alterations, and renal failure may also be present, but the grade depends on the comorbidity, the intensity of the inflammatory response, and the compensatory mechanisms of the individual 2. As far as imaging is concerned, the constellation of pneumobilia, bowel obstruction, and an aberrant gallstone referred to as Rigler’s triad is highly suggestive of Bouveret syndrome but is only found in 40% to 50% of cases 2. Ultrasound may be useful, showing possible cholecystitis, dilated stomach, pneumobilia, and ectopic location of gallstone, yet bowel gas makes it suboptimal. If the gallbladder is contracted, it may be difficult to detect the exact location of the stone (orthotopic or ectopic) using ultrasound 27.

Imaging studies

Plain radiograph and CT scan

Abdominal radiographs, though non-specific, may help identify Bouveret syndrome. Rigler triad (bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone) is seen only in about 40% to 50% of cases. However, abdominal radiographs are only diagnostic in 21% of Bouveret syndrome cases. Computed tomography (CT) scan is the imaging modality of choice, with an overall 93% sensitivity, 100% specificity, and 99% diagnostic accuracy. In addition to its higher accuracy than plain radiograph or ultrasound, it can also provide important information about the presence of a fistula, presence of an abscess, inflammatory state of the surrounding lumen and tissue, size of gallstone, and the number of gallstones. In cases where the offending gallstone is identified, its size (and hence the likelihood of mechanical obstruction) may be underestimated if only the calcified portion of the stone is measured 8.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

In patients unable to tolerate oral contrast or with intense vomiting, as well as in cases with iso-attenuating stones, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be utilized, as it distinguishes stones from fluid, visualizes the fistula with good precision, and does not require the use of oral contrast material. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is another option, with diagnostic and therapeutic advantages. However, simultaneous removal of the stone is only successful in a minority of cases and can be associated with further complications. In about 20% to 40% of cases, the final diagnosis is established intra-operatively when a patient is undergoing laparotomy for small bowel obstruction of an unknown cause. This applies particularly to the 15% to 25% of gallstones that are iso-attenuating and not visible on CT scans 28.

Ultrasound

Sonography may detect the presence of a cholecystoenteric fistula, residual gallstones and gastric outlet obstruction.

Bouveret syndrome treatment

The chance of spontaneous resolution of Bouveret syndrome after conservative treatment is rare 14. Also, a dislodged gallstone can cause distal obstruction. Endoscopic intervention is currently the first line of treatment of Bouveret syndrome, because removal may be performed with mechanical, electrohydraulic, or laser lithotripsy 2. Decompression of the distended stomach by a nasogastric tube should be performed prior to therapeutic endoscopy to reduce the risk of aspiration. Many case reports of successful endoscopic management have been published in recent decades 29. The first successful endoscopic visualization and extraction of gallstones of three cases was published in 1985 30. Subsequently, endoscopic nets and lithotripsy modalities were developed for gallstone extraction. This minimally invasive approach enjoys lower mortality and morbidity rates of endoscopy vs. surgery (1.6% vs. 17.3%) for Bouveret syndrome 29. However, it has a markedly reduced success rate in contrast to surgical intervention (43.0% vs. 94.1%) 17.

Minimally invasive treatment

Minimally invasive treatment includes endoscopic retrieval, in addition to mechanical, electrohydraulic lithotripsy, laser, and extracorporeal shock wave. Endoscopic intervention is currently the first line of treatment of Bouveret syndrome, because removal may be performed with mechanical, electrohydraulic, or laser lithotripsy 2. Extraction of impacted stones by endoscopic graspers, nets, snares, or baskets can be tried. An esophageal overtube or latex rubber can be used to avoid esophageal injury during extraction. Endoscopic nets are reportedly more effective for treating smaller-sized gallstones than larger ones 31. Gallstones of diameter exceeding 2.5 cm need lithotripsy fragmentation to enhance easy passage through the distal alimentary tract and safe removal.

Mechanical lithotripsy is a common method used, and fluoroscopy is a preferable adjunct to avoid the instrument wrongly entering the cholecystoenteric fistula. The other common method of lithotripsy is electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL). High electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) intensity may be needed because of the large gallstones commonly found in cases of Bouveret syndrome 32. The other problem with electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) is that incidental focusing of the shock waves on the intestine wall may cause bleeding and perforation 33. Other endoscopic methods are laser lithotripsy and extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL). Endoscopic laser lithotripsy was used in the mid-1980s for bile duct stones treatment 34. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy has been reported to be effective and safe in treating complicated bile duct stones 35. The benefit of using endoscopic laser lithotripsy is the precise targeting of energy onto the stone with minimal tissue injury. The direct visual control of the laser application makes the treatment technically easy and safe 36. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved holmium and neodymium yttrium aluminum garnet lasers as treatments and is available in the market 37. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) has a higher failure rate and is limited by lacking endoscopic control. Utilization of intraoperative ultrasound during ESWL is advisable to tackle the gallstones, as the intraabdominal gases often impede plain x-ray 29.

Of all the successful endoscopic interventions which have been published in the recent decades, visualization of the gallstones was achieved in approximately two-thirds of cases 29. Moreover, less than two-thirds can be removed successfully 14. Endoscopic modality may require more than one session, and fragments of stones can cause postoperative gallstone ileus 29. Therefore, it is essential to remove these fragments at the end of the procedure 38. Even so, endoscopic modalities present convenient alternatives, especially when patients are not suitable for surgery. Also, the success rate of these techniques will continue to increase in the future as technology continues to progress.

Surgery

Surgery was considered first-line treatment in the past and has demonstrated higher success rates than the minimally invasive modality with up to 90% for enteric or gastric lithotomy alone and up to 82% with simultaneous fistula repair and cholecystectomy 14. Surgery often is not desirable as the patients are often poor surgical candidates secondary to concomitant illnesses and advanced age. Moreover, surgery has remarkable morbidity and mortality, 37.5% and 11%, respectively 39. As Bouveret syndrome is usually seen in elderly patients with significant comorbidities, surgery is not feasible for many of these patients 2. Surgical options may need to be considered to treat patients with Bouveret syndrome when an endoscopic attempt is unsuccessful or no technical expertise is available. The surgical approach consists of open gastrotomy, pylorotomy, or duodenotomy at or proximal to the site of obstruction. Gastrotomy can be used for stone removal if it is possible to manipulate an impacted duodenal gallstone into the stomach 40. With a distal duodenal impacted stone or a migrated stone into the proximal part of the jejunum, an enterotomy distal to Trietz ligament may be used for stone removal. The distal part of the small intestine must be examined to ensure no other migrated large stones may result in postoperative ileus. Endoscopy may be used as an adjunct to help maneuver the stone into a more suitable location to perform enterotomy or gastrotomy if the gallstone is detected in a difficult area to access during open surgery in one or two sessions 41.

Open surgery of Bouveret syndrome has high morbidity and mortality. When laparoscopic equipment and expertise are available, laparoscopic enterolithotomy should be considered the preferred approach and has been reported as effective and safe in managing this condition in the failure or unavailability of endoscopic therapies 42. However, higher rates of conversion are seen in these difficult cases 43. As with an open approach, stones can be removed by a laparoscope through duodenotomy, pylorotomy, or gastrotomy. After removing impacted gallstones, the small intestine needs to be examined to ensure there are no retained stones.

Cholecystectomy and fistula repair in one or a multi-step approach to treat Bouveret syndrome is debatable. Most patients are poor surgical candidates as they are older and have multiple comorbidities. Cholecystectomy with fistula repair is generally not recommended as the benefits of cholecystectomy in these patients generally outweigh the risks of further operations or complications from gallstones. However, there is always a risk for recurrent gallstone ileus and gallstone pancreatitis if the fistula is not repaired 44. It is recommended to perform cholecystectomy in younger patients as there may be an increased risk of gallbladder cancer with cholecystoenteric fistula. Also, cholecystectomy is recommended if malignancy cannot be excluded with diagnostic imaging before surgery 45. Cholecystectomy warrants consideration in other special conditions, including the previous history of gallstone ileus, common bile duct stone, and gallstone pancreatitis 46.

Bouveret syndrome prognosis

Bouveret syndrome generally carries a good prognosis provided timely diagnosis and management. Bouveret syndrome remains difficult to diagnose as the symptoms are nonspecific and the physical exam findings may be subtle. Bouveret syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis in elderly patients who have a history of chronic cholecystitis and presenting with repeated episodes of nausea and vomiting (present in 85% of patients), abdominal distension, and abdominal pain (present in 70% of patients). The patient may also exhibit epigastric and right hypochondrium pain and signs of dehydration and weight loss. Usually, the symptoms begin 5 to 7 days before patients seek medical consultation. Notably, the intensity of the pain often does not correlate with the underlying anatomic alteration.

The key to diagnosing patients with Bouveret syndrome is maintaining a high level of suspicion in patients with a history of cholelithiasis and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction. The typical patient is an older woman with multiple comorbidities, including a history of cholelithiasis, presenting with symptoms of bowel obstruction and/or gastric outlet obstruction. The largest review of 128 cases of Bouveret syndrome found that over 85% of patients diagnosed presented with nausea and vomiting 14. Abdominal pain was also seen in ~70% of patients. Although less common, patients may also present with symptoms suggesting a gastrointestinal bleed, including hematemesis (15% of patients) and/or melena (6% of patients) 15.

Most patients presenting for a suspected gastrointestinal tract obstruction are screened with an abdominal X-ray. Findings suggestive of Bouveret syndrome include Rigler’s triad: a dilated stomach, pneumobilia, and a radio-opaque shadow suggesting anenteric gallstone. In patients presenting with pain in the right upper quadrant, an ultrasound may be performed. The study may demonstrate cholelithiasis with or without signs of cholecystitis, including gallbladder wall thickening or pericholecystic fluid. Upper gastrointestinal series with oral contrast may give more insight to an obstructing mass by showing a filling defect, gallstone, dilation of the stomach or duodenum, pneumobilia, and/or outlet obstruction. In rare cases, there may be contrast extravasation into the gallbladder indicating a patent cholecystoduodenal or cholecystogastric fistula 14.

References- Abou-Saif A, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of gallstone disease: Mirizzi syndrome, cholecystocholedochal fistula, and gallstone ileus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002 Feb;97(2):249-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05451.x

- Turner AR, Kudaravalli P, Al-Musawi JH, et al. Bouveret Syndrome (Bilioduodenal Fistula) [Updated 2022 Mar 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430738

- Ferhatoğlu MF, Kartal A. Bouveret’s Syndrome: A Case-Based Review, Clinical Presentation, Diagnostics and Treatment Approaches. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2020 Mar 25;54(1):1-7. doi: 10.14744/SEMB.2018.03779

- Haddad FG, Mansour W, Deeb L. Bouveret’s Syndrome: Literature Review. Cureus. 2018 Mar 10;10(3):e2299. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2299

- Jin L, Naidu K. Bouveret syndrome-a rare form of gastric outlet obstruction. J Surg Case Rep. 2021 May 19;2021(5):rjab183. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjab183

- Philipose J, Khan HM, Ahmed M, Idiculla PS, Andrawes S. Bouveret’s Syndrome. Cureus. 2019 Apr 9;11(4):e4414. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4414

- Patel A, Agarwal S. The yellow brick road of Bouveret syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Aug;12(8):A24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.03.028

- Gan S, Roy-Choudhury S, Agrawal S, Kumar H, Pallan A, Super P, Richardson M. More than meets the eye: subtle but important CT findings in Bouveret’s syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Jul;191(1):182-5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3418

- Wang F, Du ZQ, Chen YL, Chen TM, Wang Y, Zhou XR. Bouveret syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2019 Dec 6;7(23):4144-4149. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4144

- Ramos GP, Chiang NE. Bouveret’s Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018 Apr 5;378(14):1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1711592

- Mavroeidis VK, Matthioudakis DI, Economou NK, Karanikas ID. Bouveret syndrome-the rarest variant of gallstone ileus: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:839370. doi: 10.1155/2013/839370

- Lassandro F, Gagliardi N, Scuderi M, Pinto A, Gatta G, Mazzeo R. Gallstone ileus analysis of radiological findings in 27 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2004 Apr;50(1):23-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.11.011

- Qasaimeh GR, Bakkar S, Jadallah K. Bouveret’s Syndrome: An Overlooked Diagnosis. A Case Report and Review of Literature. Int Surg. 2014 Nov-Dec;99(6):819-23. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00087.1

- Cappell MS, Davis M. Characterization of Bouveret’s syndrome: a comprehensive review of 128 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Sep;101(9):2139-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00645.x

- Caldwell KM, Lee SJ, Leggett PL, Bajwa KS, Mehta SS, Shah SK. Bouveret syndrome: current management strategies. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018 Feb 15;11:69-75. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S132069

- Kelly M. Kimball, Eric Kiza, Tyler Kimball, et al; Bouveret Syndrome: Rare but Quite Impactful. AIM Clinical Cases.2022;1:e220293. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0293

- Ong J, Swift C, Stokell BG, Ong S, Lucarelli P, Shankar A, Rouhani FJ, Al-Naeeb Y. Bouveret Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Endoscopic Therapy and a Novel Predictive Tool to Aid in Management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Oct;54(9):758-768. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001221

- Warren DJ, Peck RJ, Majeed AW. Bouveret’s Syndrome: a Case Report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2008;2(4):14-7. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v2i4.60

- Alemi F, Seiser N, Ayloo S. Gallstone Disease: Cholecystitis, Mirizzi Syndrome, Bouveret Syndrome, Gallstone Ileus. Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Apr;99(2):231-244. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.12.006

- Yılmaz EM, Cartı EB, Kandemir A. Rare cause of duodenal obstruction: Bouveret syndrome. Turk J Surg. 2018 Aug 28:1-3. doi: 10.5152/turkjsurg.2017.3794

- Osman K, Maselli D, Kendi AT, Larson M. Bouveret’s syndrome and cholecystogastric fistula: a case-report and review of the literature. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020 Aug;13(4):527-531. doi: 10.1007/s12328-020-01114-7

- Langhorst J, Schumacher B, Deselaers T, Neuhaus H. Successful endoscopic therapy of a gastric outlet obstruction due to a gallstone with intracorporeal laser lithotripsy: a case of Bouveret’s syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Feb;51(2):209-13. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70421-4

- Shinoda M, Aiura K, Yamagishi Y, Masugi Y, Takano K, Maruyama S, Irino T, Takabayashi K, Hoshino Y, Nishiya S, Hibi T, Kawachi S, Tanabe M, Ueda M, Sakamoto M, Hibi T, Kitagawa Y. Bouveret’s syndrome with a concomitant incidental T1 gallbladder cancer. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct;3(5):248-53. doi: 10.1007/s12328-010-0170-0

- Sharma D, Jakhetia A, Agarwal L, Baruah D, Rohtagi A, Kumar A. Carcinoma Gall Bladder with Bouveret’s Syndrome: A Rare Cause of Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Indian J Surg. 2010 Aug;72(4):350-1. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0145-x

- Su HL, Tsai MJ. Bouveret syndrome. QJM. 2018 Jul 1;111(7):489-490. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcy020

- Haddad FG, Mansour W, Mansour J, Deeb L. From Bouveret’s Syndrome to Gallstone Ileus: The Journey of a Migrating Stone! Cureus. 2018 Mar 26;10(3):e2370. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2370

- Di Re AM, Punch G, Richardson AJ, Pleass H. Rare case of Bouveret syndrome. ANZ J Surg. 2019 May;89(5):E198-E199. doi: 10.1111/ans.14215

- Yu YB, Song Y, Xu JB, Qi FZ. Bouveret’s syndrome: A rare presentation of gastric outlet obstruction. Exp Ther Med. 2019 Mar;17(3):1813-1816. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7150

- Dumonceau JM, Devière J. Novel treatment options for Bouveret’s syndrome: a comprehensive review of 61 cases of successful endoscopic treatment. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov;10(11):1245-1255. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2016.1241142

- Iñíguez A, Butte JM, Zúñiga JM, Crovari F, Llanos O. Síndrome de Bouveret: Resolución endóscopica y quirúrgica de cuatro casos clínicos [Bouveret syndrome: report of four cases]. Rev Med Chil. 2008 Feb;136(2):163-8. Spanish.

- Jindal A, Philips CA, Jamwal K, Sarin SK. Use of a Roth Net Platinum Universal Retriever for the endoscopic management of a large symptomatic gallstone causing Bouveret’s syndrome. Endoscopy. 2016 Sep;48(S 01):E308. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-116430

- Kaushik N, Moser AJ, Slivka A, Chandrupatala S, Martin JA. Gastric outlet obstruction caused by gallstones: case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2005 Mar;50(3):470-3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2460-9

- Binmoeller KF, Brückner M, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Treatment of difficult bile duct stones using mechanical, electrohydraulic and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1993 Mar;25(3):201-6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010293

- Cotton PB, Kozarek RA, Schapiro RH, Nishioka NS, Kelsey PB, Ball TJ, Putnam WS, Barkun A, Weinerth J. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy of large bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 1990 Oct;99(4):1128-33. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90634-d

- Lv S, Fang Z, Wang A, Yang J, Zhang W. Choledochoscopic Holmium Laser Lithotripsy for Difficult Bile Duct Stones. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017 Jan;27(1):24-27. doi: 10.1089/lap.2016.0289

- Rogart JN, Perkal M, Nagar A. Successful Multimodality Endoscopic Treatment of Gastric Outlet Obstruction Caused by an Impacted Gallstone (Bouveret’s Syndrome). Diagn Ther Endosc. 2008;2008:471512. doi: 10.1155/2008/471512

- ASGE Technology Committee, Watson RR, Parsi MA, Aslanian HR, Goodman AJ, Lichtenstein DR, Melson J, Navaneethan U, Pannala R, Sethi A, Sullivan SA, Thosani NC, Trikudanathan G, Trindade AJ, Maple JT. Biliary and pancreatic lithotripsy devices. VideoGIE. 2018 Sep 26;3(11):329-338. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2018.07.010

- Alsolaiman MM, Reitz C, Nawras AT, Rodgers JB, Maliakkal BJ. Bouveret’s syndrome complicated by distal gallstone ileus after laser lithotropsy using Holmium: YAG laser. BMC Gastroenterol. 2002 Jun 18;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-230x-2-15

- Pavlidis TE, Atmatzidis KS, Papaziogas BT, Papaziogas TB. Management of gallstone ileus. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10(4):299-302. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0806-7

- Gallego Otaegui L, Sainz Lete A, Gutiérrez Ríos RD, Alkorta Zuloaga M, Arteaga Martín X, Jiménez Agüero R, Medrano Gómez MÁ, Ruiz Montesinos I, Beguiristain Gómez A. A rare presentation of gallstones: Bouveret´s syndrome, a case report. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016 Jul;108(7):434-6.

- Stein PH, Lee C, Sejpal DV. A Rock and a Hard Place: Successful Combined Endoscopic and Surgical Treatment of Bouveret’s Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Dec;13(13):A25-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.044

- Newton RC, Loizides S, Penney N, Singh KK. Laparoscopic management of Bouveret syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Apr 22;2015:bcr2015209869. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-209869

- Hussain A. Difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: current evidence and strategies of management. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011 Aug;21(4):211-7. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318220f1b1

- Jafferbhoy S, Rustum Q, Shiwani M. Bouveret’s syndrome: should we remove the gall bladder? BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Apr 1;2011:bcr0220113891. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3891

- Lee W, Han SS, Lee SD, Kim YK, Kim SH, Woo SM, Lee WJ, Koh YW, Hong EK, Park SJ. Bouveret’s syndrome: a case report and a review of the literature. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2012 May;16(2):84-7. doi: 10.14701/kjhbps.2012.16.2.84

- Lopes CV, Lima FK, Hartmann AA. Bouveret syndrome and pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2017 Feb;49(S 01):E62-E63. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-123499