What is bullae skin

Bullae are large blisters or large blebs, which are fluid-filled sacs on the outer layer of your skin. Bullae form because of rubbing, heat, or diseases of the skin. They are most common on your hands and feet. Small skin blisters less than 5 mm in diameter are called vesicles. Bullae may break or the roof of the blister may become detached forming an erosion. Exudation of serous fluid forms crust.

Blisters usually just need time to heal on their own. Keep a blister clean and dry and cover it with a bandage until it goes away. While it heals, try to avoid putting pressure on the area or rubbing it.

You should contact your health care provider if

- The blister looks infected – if it is draining pus, or the area around the blister is red, swollen, warm, or very painful

- You have a fever

- You have several blisters, especially if you cannot figure out what is causing them

- You have health problems such as circulation problems or diabetes

Normally you don’t want to drain a blister, because of the risk of infection. But if a blister is large, painful, or looks like it will pop on its own, you can drain the fluid.

How to prevent and treat blisters

To prevent chafing that can lead to blisters, dermatologists recommend the following tips:

- Protect your feet: To prevent blisters on your feet, wear nylon or moisture-wicking socks. If wearing one pair of socks doesn’t help, try wearing two pairs to protect your skin. You should also make sure your shoes fit properly. Shoes shouldn’t be too tight or too loose.

- Wear the right clothing: During physical activity, wear moisture-wicking, loose-fitting clothes. Avoid clothes made of cotton, as cotton soaks up sweat and moisture, which can lead to friction and chafing.

- Consider soft bandages: For problem areas, such as the feet or thighs, consider using adhesive moleskin or other soft bandages. Make sure the bandages are applied securely.

- Apply powder or petroleum jelly to problem areas: This helps reduce friction when your skin rubs together or rubs against clothing.

- Stop your activity immediately if you experience pain or discomfort, or if your skin turns red: Otherwise, you may get a blister.

If you do get a blister, be patient and try to leave it alone. Most blisters heal on their own in one to two weeks. Don’t resume the activity that caused your blister until it’s healed.

To treat a blister, dermatologists recommend the following:

- Cover the blister: Loosely cover the blister with a bandage. Bring in the sides of the bandage so that the middle of the bandage is a little raised.

- Use padding: To protect blisters in pressure areas, such as the bottom of your feet, use padding. Cut the padding into a donut shape with a hole in the middle and place it around the blister. Then, cover the blister and padding with a bandage.

- Avoid popping or draining a blister, as this could lead to infection. However, if your blister is large and very painful, it may be necessary to drain the blister to reduce discomfort. To do this, sterilize a small needle using rubbing alcohol. Then, use the needle to carefully pierce one edge of the blister, which will allow some of the fluid to drain.

- Keep the area clean and covered: Once your blister has drained, wash the area with soap and water and apply petroleum jelly. Do not remove the “roof” of the blister, as this will protect the raw skin underneath as it heals.

As your blister heals, watch for signs of an infection. If you notice any redness, pus, or increased pain or swelling, make an appointment to see your doctor or a board-certified dermatologist.

Bullae causes

Bullae often happen when there is friction – rubbing or pressure – on one spot. For example, if your shoes don’t fit quite right and they keep rubbing part of your foot. Or if you don’t wear gloves when you rake leaves and the handle keeps rubbing against your hand. Other causes of bullae include:

- Burns

- Sunburn

- Frostbite

- Eczema

- Allergic reactions

- Poison ivy, oak, and sumac

- Autoimmune diseases such as pemphigus

- Epidermolysis bullosa, an illness that causes the skin to be fragile

- Viral infections such as varicella zoster (which causes chickenpox and shingles) and herpes simplex (which causes cold sores)

- Skin infections including impetigo

Acute blistering diseases

Acute blistering diseases can be generalized or localized to one body site and are due to infection or inflammatory disorders. Although most commonly eczematous, generalized acute blistering diseases can be life-threatening and often necessitate hospitalization.

Acute blistering conditions should be investigated by taking swabs for bacterial and viral culture. A skin biopsy may be helpful in making a diagnosis.

Acute generalized blistering diseases

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis

- Neck, limbs, upper trunk

- Pseudovesicular plaques, blisters, pustules, purpura, or ulceration

- Disease associations: rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune arthritis, myeloid dysplasia

- Biopsy suggestive

Atypical enterovirus infection

- Widespread vesicular eruption

- Clears in a few days

Chickenpox/varicella

- Childhood illness; more serious in adults

- Scalp, face, oral mucosa, trunk

- Culture/PCR Herpes varicella zoster

Eczema herpeticum

- History of atopic dermatitis

- Monomorphic cluster of umbilicated vesicles

- Culture/PCR Herpes simplex

Dermatitis

- Atopic dermatitis

- Discoid eczema

Polymorphic light eruption

- Affects body sites exposed to the sun (hands, upper chest, feet

- Papules, plaques, sometimes targetoid

- May spare face

- Arises within hours of exposure to bright sunlight

Erythema multiforme

- A reaction, e.g., to infection

- An acute eruption of papules, plaques, target lesions

- Acral distribution: cheeks, elbows, knees, hands, feet

- May have mucositis (lips, conjunctiva, genitals)

Stevens-Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis

- Patient very unwell

- Mucosal involvement

- Nearly always drug-induced

- Rarely due to mycoplasma infection

- Painful red skin may come off in sheets or have multiple coalescing blisters

Drug hypersensitivity syndrome

- Drug started up to 8 weeks prior to the onset

- Morbilliform eruption that may blister (without necrolysis)

- Often, mucosal involvement

- Multiorgan damage (renal, hepatic, respiratory, hematological)

- Often, marked eosinophilia

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- Young child

- Miserable

- Red skin comes off in sheets

- Evidence of staphylococcal infection

Acute localized blistering diseases

Acute dermatitis

- Contact dermatitis

- Plant dermatitis

- Pompholyx

Bullous impetigo

- Rapidly enlarging plaque

- Swab Staphylococcus aureus

- Wound infections, scabies etc

Chilblains

- Fingers, toes

- Exposed to cold

- Purplish tender plaques

Enteroviral vesicular stomatitis

- Hand, foot and mouth

- Clears in a few days

Erysipelas

- Acute febrile illness

- Swab Streptococcus pyogenes

Fixed drug eruption

- Recurring rash, often in the same site

- Due to an intermittent drug that has been taken within 24 hours of the rash appearing

- Single or few lesions

- Central blister

Herpes simplex

- Monomorphic, umbilicated

- Culture/PCR Herpes simplex

Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Dermatomal

- Culture/PCR Herpes zoster

Insect bites and stings

- Crops of urticated papules

- Central vesicle or punctum

- Favor exposed sites

Miliaria

- Central trunk

- Sweat rash

- Vesicles are very superficial

Necrotizing fasciitis

- Very sick; septic shock

- Rapid spread of cellulitis with purpura/blistering

- Anesthetic areas in early lesions

- Bacterial culture essential

Transient acantholytic dermatosis

- Acute or chronic

- Elderly males

- Itchy or asymptomatic

- Crusted papules

Trauma

- History of injury or neuropathy

- Friction, thermal burns, ultraviolet radiation sunburns, chemical burns, fracture

Chronic blistering diseases

Diagnosis of chronic blistering diseases often requires skin biopsy for histopathology and direct immunofluorescence. A blood test for specific antibodies (indirect immunofluorescence) may also prove helpful in making the diagnosis of an immunobullous disease.

Blistering genodermatoses

Epidermolysis bullosa

- Various types

- Onset at birth or early childhood

Fogo selvagem

- Also called endemic pemphigus foliaceus

- Onset at childhood or adolescence

Mastocytosis

- Various types

- Often, onset in childhood

Benign familial pemphigus

- Also called Hailey-Hailey disease

- Confined to flexures

Chronic acquired blistering

Bullous pemphigoid

- Mainly cutaneous (rarely mucosal)

- Mostly affects the elderly (rarely infants, children)

- Often associated stroke or dementia

- Subepidermal bullae

- Eczematous or urticarial precursors

Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Associated gluten-sensitive enteropathy

- Intensely itchy; vesicles often removed by scratching leaving erosions

- Symmetrical on scalp, shoulders, elbows, knees, buttocks

Other immunobullous diseases

- Cicatricial pemphigoid

- Pemphigoid gestationis

- Linear IgA dermatosis

- Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Pemphigus foliaceus

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus

- Drug-induced pemphigus

- IgA pemphigus

Porphyria cutanea tarda

- Metabolic photosensitivity

- Skin fragility, bullae, milia

- Dorsum of hands, face

- Onset in middle age

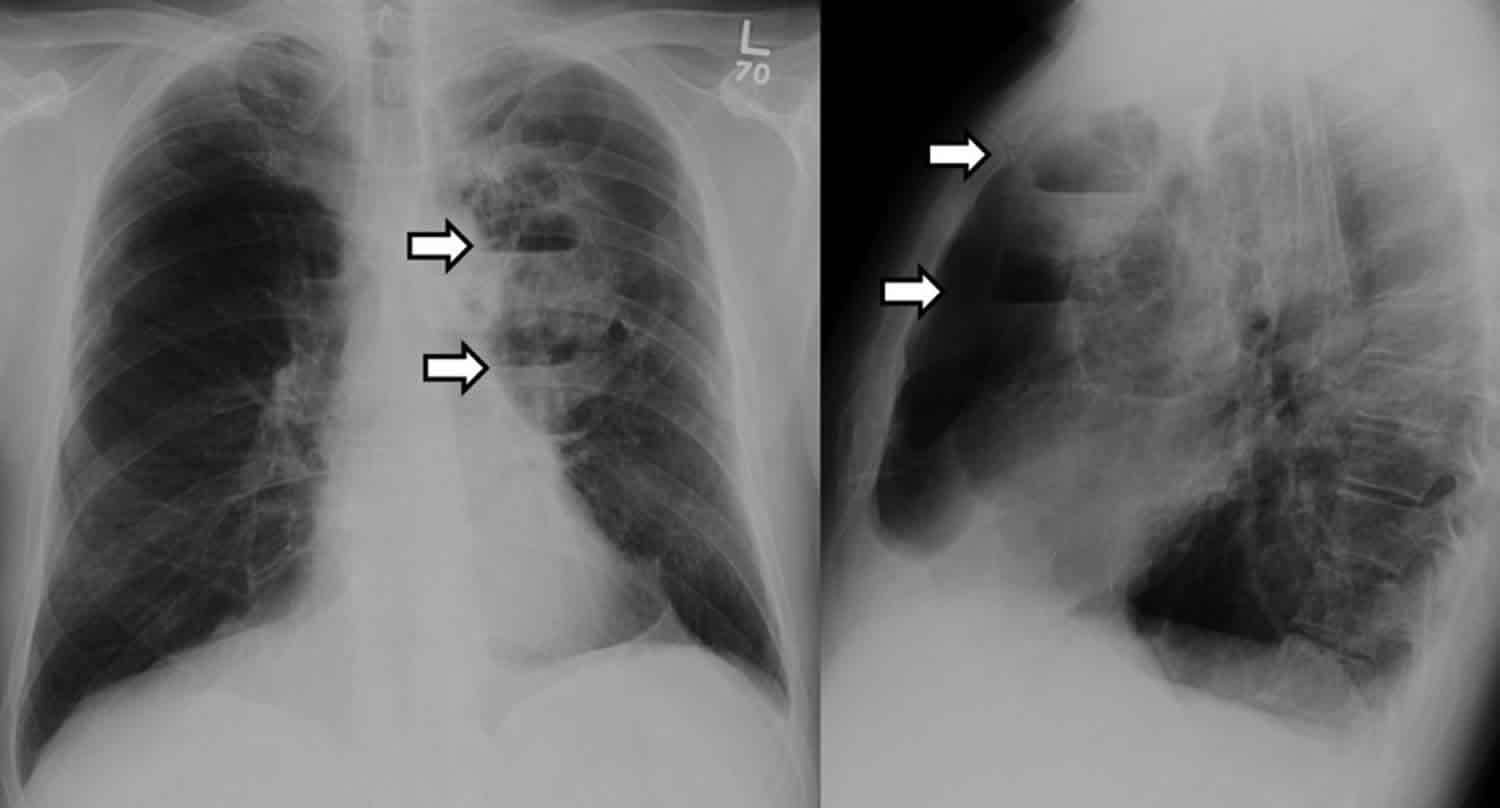

What is bullae in lungs

Pulmonary bullae are large empty spaces that form from hundreds of destroyed alveoli in the lungs destroyed by generalized emphysema 1. These air spaces can become so large that they crowd out the better functioning lung and interfere with breathing. Bullae can be as large as half the lung. In addition to reducing the amount of space available for the lung to expand, giant bullae can increase your risk of pneumothorax.

To prevent emphysema, don’t smoke and avoid breathing secondhand smoke. Wear a mask to protect your lungs if you work with chemical fumes or dust.

Treatment typically involves surgery, although a variety of procedures have been proposed, including local excision of the bullae, plication, stapler resection, lobectomy, and videothoracoscopy 2. Surgical therapy is indicated when patients have incapacitating dyspnea or for patients who have complications related to bullous disease, such as infection or pneumothorax 3. Most patients with lung bullae have a significant cigarette smoking history, although cocaine smoking, pulmonary sarcoidosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, 1-antichymotrypsin deficiency, Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and inhaled fiberglass exposure have all been implicated 4. Additionally, marijuana smoking has resulted in extensive emphysematous bullous disease seen in many young patients 5.

Bullae which enlarge enough to compress adjacent lung tissue are best diagnosed by CT scan. A “double-wall sign” on chest CT, demonstrating air on both sides of the bulla wall, signifies an associated pneumothorax with the bulla 6. In addition to chest CT, these patients should undergo arterial blood gases and lung function tests, The decision to operate is often a challenging one. Patients should undergo surgical resection when they have incapacitating dyspnea with large bullae that fill more than 30% of the hemithorax and result in the compression of healthy adjacent lung tissue 7. In addition, operation is indicated for patients who have complications related to bullous disease such as infection or pneumothorax 8.

There are two surgical approaches for resecting giant lung bullae. Stapling resection of the entire bulla, either through a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or open approach, is the most common technique 7. Pericardial strips can be used along the staple line to assist in control of air leaks since the surrounding lung tissue is often diseased. Another operative approach is the modified Monaldi technique, which involves opening the bulla, placing a purse-string suture at the neck of the bulla and closing the overlying bulluous sac with a running back-and-forth plicating stitch 9. Both techniques have been shown to be effective. Smoking cessation and aggressive pulmonary rehabilitation are also important for successful treatment of patients with bullous lung disease.

References- Giant bullous lung disease: evaluation, selection, techniques, and outcomes. Greenberg JA, Singhal S, Kaiser LR. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2003 Nov; 13(4):631-49.

- Santini M, Fiorelli A, Vicidomini G, et al. Endobronchial treatment of giant emphysematous bullae with one-way valves: a new approach for surgically unfit patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40:1425–1431

- Vigneswaran WT, Townsend ER, Fountain SW. Surgery for bullous disease of the lung. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1992;6:427–430

- Bullous Lung Disease. https://www.ctsnet.org/article/bullous-lung-disease

- Johnson MK, Smith RP, Morrison D, et al. Large lung bullae in marijuana smokers. Thorax. 2000;55:340–342

- Waitches GM, Stern EJ, Dubinsky TJ. Usefulness of the double-wall sign in detecting pneumothorax in patients with giant bullous emphysema. Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:1765-8

- Greenberg JA, Singhal S, Kaiser LR. Giant bullous lung disease: evaluation, selection, techniques, and outcomes. Chest Surg Clin N Am 2003;13:631-49

- Vigneswaran WT, Townsend ER, Fountain SW. Surgery for bullous disease of the lung. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1992;6:427-30

- Shah SS, Goldstraw P. Surgical treatment of bullous emphysema: experience with the Brompton technique. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:1452-6