CADASIL

CADASIL is an acronym that stands for 1:

- Cerebral – relating to the brain

- Autosomal

- Dominant – a form of inheritance in which one copy of an abnormal gene is necessary for the development of a disorder

- Arteriopathy – disease of the arteries (blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart)

- Subcortical – relating to specific areas of the brain supplied by deep small blood vessels

- Infarcts – tissue loss in the brain caused by lack of blood flow to the brain, which occurs when circulation through the small arteries is severely reduced or interrupted

- Leukoencephalopathy – lesions in the brain white matter caused by the disease and observed on MRI

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy or CADASIL, is a rare genetic disorder that causes stroke and other impairments. CADASIL affects blood flow in small blood vessels, particularly cerebral vessels within the brain. The muscle cells surrounding these blood vessels (vascular smooth muscle cells) are abnormal and gradually die. In the brain, the resulting blood vessel damage (arteriopathy) can cause migraines, often with visual sensations or auras, or recurrent seizures (epilepsy).

Damaged blood vessels reduce blood flow and can cause areas of tissue death (infarcts) throughout the body. An infarct in the brain can lead to a stroke. In individuals with CADASIL, a stroke can occur at any time from childhood to late adulthood, but typically happens during mid-adulthood. People with CADASIL often have more than one stroke in their lifetime. Recurrent strokes can damage the brain over time. Strokes that occur in the subcortical region of the brain, which is involved in reasoning and memory, can cause progressive loss of intellectual function (dementia) and changes in mood and personality.

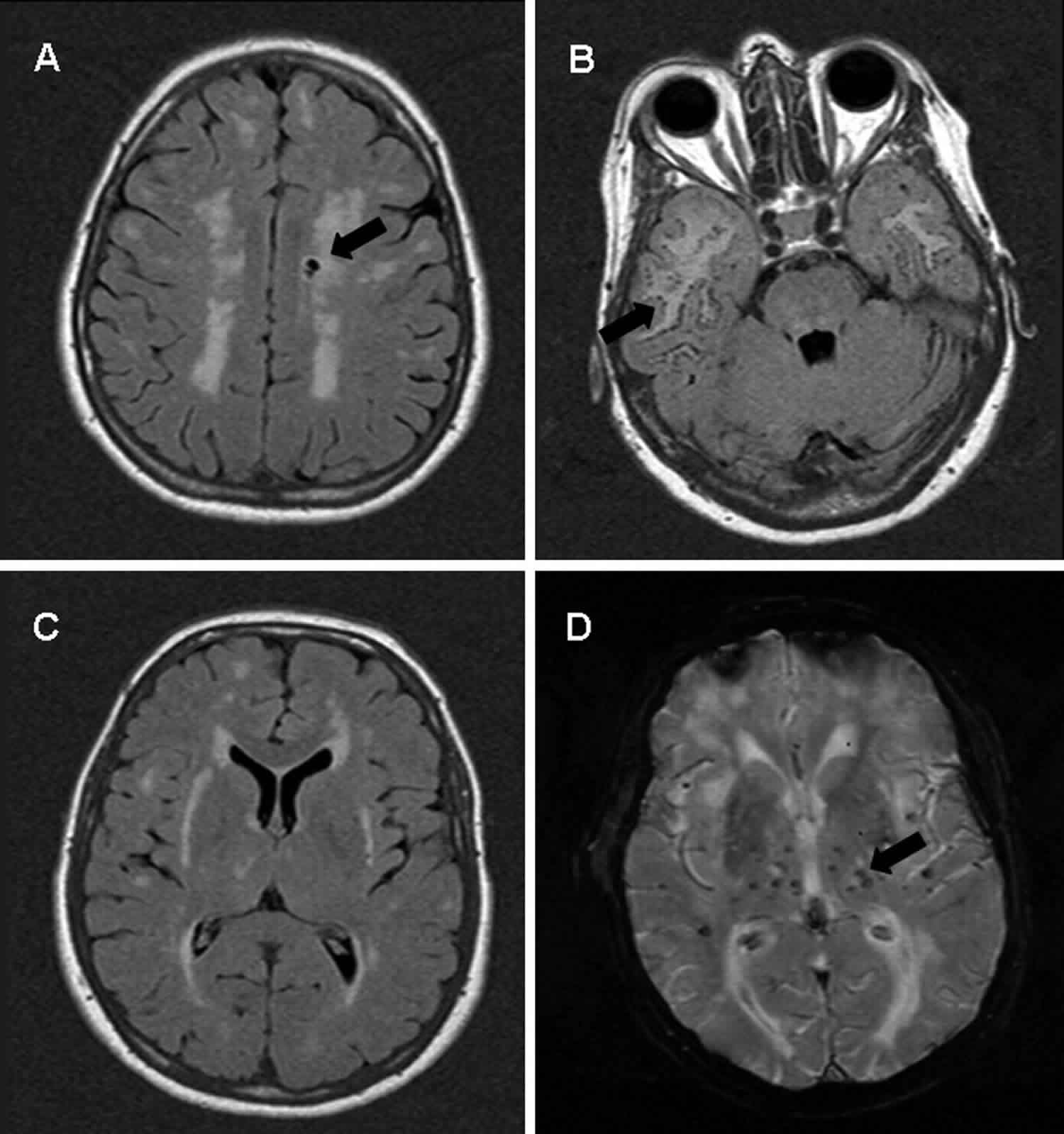

Many people with CADASIL also develop leukoencephalopathy, which is a change in a type of brain tissue called white matter that can be seen with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The most common signs and symptoms of CADASIL are caused by damage to small blood vessels, especially those within the brain and include: stroke, cognitive impairment, migraine with aura, and psychiatric disturbances. These symptoms are 2:

- Recurrent ischemic strokes (transient ischemic attack/stroke) in adulthood that may lead to severe disability such as an inability to walk and urinary incontinence. The average age at onset for stroke-like episodes is 46 years. Transient ischemic attacks and stroke are reported in approximately 85% of symptomatic individuals

- Progressive cognitive decline with dementia developing in about 75% of affected people including significant difficulty with reasoning and memory

- Migraine, usually with aura, as the first symptom in the third decade of life

- Psychiatric problems such as mood disturbances (apathy and depression), presenting in about 30% of people with CADASIL

- Seizures with epilepsy is present in 10% of affected people and usually presents at middle age

- Diffuse white matter lesions and subcortical infarcts on neuroimaging.

Less common signs and symptoms may include 3:

- Other psychiatric issues such as gambling, a seizure lasting 30 minutes or longer, or a cluster of shorter seizures for 30 minutes or more with little or no recovery between episodes (recurrent status epilecticus), psychosis, and bipolar disease

- Slow movements and tremors (parkisionism)

- Memory loss (amnesia)

- Dysfunction of one or more peripheral nerves, typically causing numbness or weakness (neuropathy)

- Muscular weakness due to a muscular disease (myopathy)

- Confusion, fever and coma (CADASIL coma)

- Acute vestibular syndrome (rapid onset [over seconds to hours] of vertigo, nausea/vomiting, and abnormal gait in association with head-motion intolerance and abnormal eye movements, lasting days to weeks)

- Spinal cord involvement.

CADASIL affects males and females in equal numbers. The disorder is found worldwide and affects all races. The disease affects approximately 2 to 5 of 100,000 people. Research suggests that the disorder often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed making it difficult to determine the true frequency of CADASIL in the general population. The age at which the signs and symptoms of CADASIL first begin varies greatly among affected individuals, as does disease progression varies greatly from one person to another, even among members of the same family.

CADASIL is not associated with the common risk factors for stroke and heart attack, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol, although some affected individuals might also have these health problems.

There is no treatment of proven efficacy for CADASIL 2. Standard supportive treatment for stroke; the effect of thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of stroke remains unknown. Migraine should be treated symptomatically. Standard treatment for psychiatric disturbance. Supportive care (practical help, emotional support, and counseling) is appropriate for affected individuals and their families 2.

Can CADASIL cause lesions in the brain?

Yes. CADASIL can cause changes (lesions) in the brain. CADASIL affects the arteries in the brain, causing them to narrow or break down. This affects the flow of blood to the brain, reducing the amount of oxygen which is delivered, which can damage brain tissue over time. Damaged tissue could appear as a lesion on a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test 4.

Is it possible to have multiple sclerosis and CADASIL?

Theoretically, it is possible for an individual to develop both multiple sclerosis and CADASIL. However, because both conditions are uncommon, it would be extremely unlikely to have both. It is more likely that an individual has only one of these conditions. The two conditions can cause similar symptoms, such as changes in brain tissue (lesions) shown on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can complicate the process of arriving at the correct diagnosis 2.

Articles in the medical literature mention that MS is the most common misdiagnosis for individuals with CADASIL 5. Several tests may help to clarify which diagnosis is correct: the finding of a NOTCH3 mutation on genetic testing is considered diagnostic of CADASIL; the finding of certain proteins in cerebral spinal fluid from a spinal tab may help establish a diagnosis of MS 6.

If a parent has CADASIL, are his or her children at risk to inherit the condition?

Every child of an individual with one NOTCH3 mutation has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the mutation 2.

Can CADASIL skip a generation?

CADASIL is thought to have 100% penetrance 2. This means that all people who inherit the mutated gene responsible for CADASIL will be affected. However, the age of onset, severity of symptoms, and progression of the disease varies. Likewise, those who do not inherit the mutated gene will not be affected.

Most people diagnosed with CADASIL have an affected parent. However, the family history may appear to be negative because of failure to recognize symptoms in family members, early death of an affected parent before the onset of symptoms, or late onset of the disease in the affected parent 2.

If molecular genetic testing has identified the specific mutation present in the NOTCH3 gene in an affected family member, testing of at-risk, asymptomatic adult relatives is possible.

- If the son or daughter of an affected person with an identified mutation is tested and is not found to have the mutation, they will be unaffected and also are not at risk to pass the mutation on to their children or (grandchildren). This means that CADASIL cannot skip a generation; the mutation would not “reappear” in a future generation once it has not been passed down.

- If a family member does have the mutation and is asymptomatic, while they will become affected at some point, genetic testing is not useful in predicting age of onset, severity, type of symptoms, or rate of progression 2.

In a family with an established diagnosis of CADASIL, testing is appropriate to consider in symptomatic people regardless of age. However, testing of asymptomatic people who are younger than 18 years who are at risk for adult-onset disorders for which no treatment exists is not considered appropriate 2.

Genetic counseling is strongly recommended for people considering genetic testing for a family history of CADASIL.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

CADASIL causes

Mutations or changes in the NOTCH3 gene, which maps to the short arm of chromosome 19 (19p13.2-p13.1) 7 cause CADASIL. The NOTCH3 gene provides instructions for producing the Notch3 receptor protein, which is important for the normal function and survival of vascular smooth muscle cells. When certain molecules attach (bind) to Notch3 receptors, the receptors send signals to the nucleus of the cell. These signals then turn on (activate) particular genes within vascular smooth muscle cells.

NOTCH3 gene mutations lead to the production of an abnormal Notch3 receptor protein that impairs the function and survival of vascular smooth muscle cells. Disruption of Notch3 functioning can lead to the self-destruction (apoptosis) of these cells. Ultimately, NOTCH3 mutations lead to progressive damage to the small blood vessels in the brain, premature destruction of smooth muscle cells, and narrowing of the lumen and thickening the vessel wall of the small blood vessels. Microscopic protein accumulations of debris called granular osmiophilic material (GOM) accumulate in blood vessels of CADASIL patients. As a consequence of these changes, there is reduction of blood flow to the brain causing small strokes (or lacunes), small bleeds (microbleeds), dilated spaces surrounded the vessels (dilated perivascular spaces) and tissue loss in the surface of the brain (cortex) as well underneath the cortex (subcortical region).

In the brain, the loss of vascular smooth muscle cells results in blood vessel damage that can cause the signs and symptoms of CADASIL.

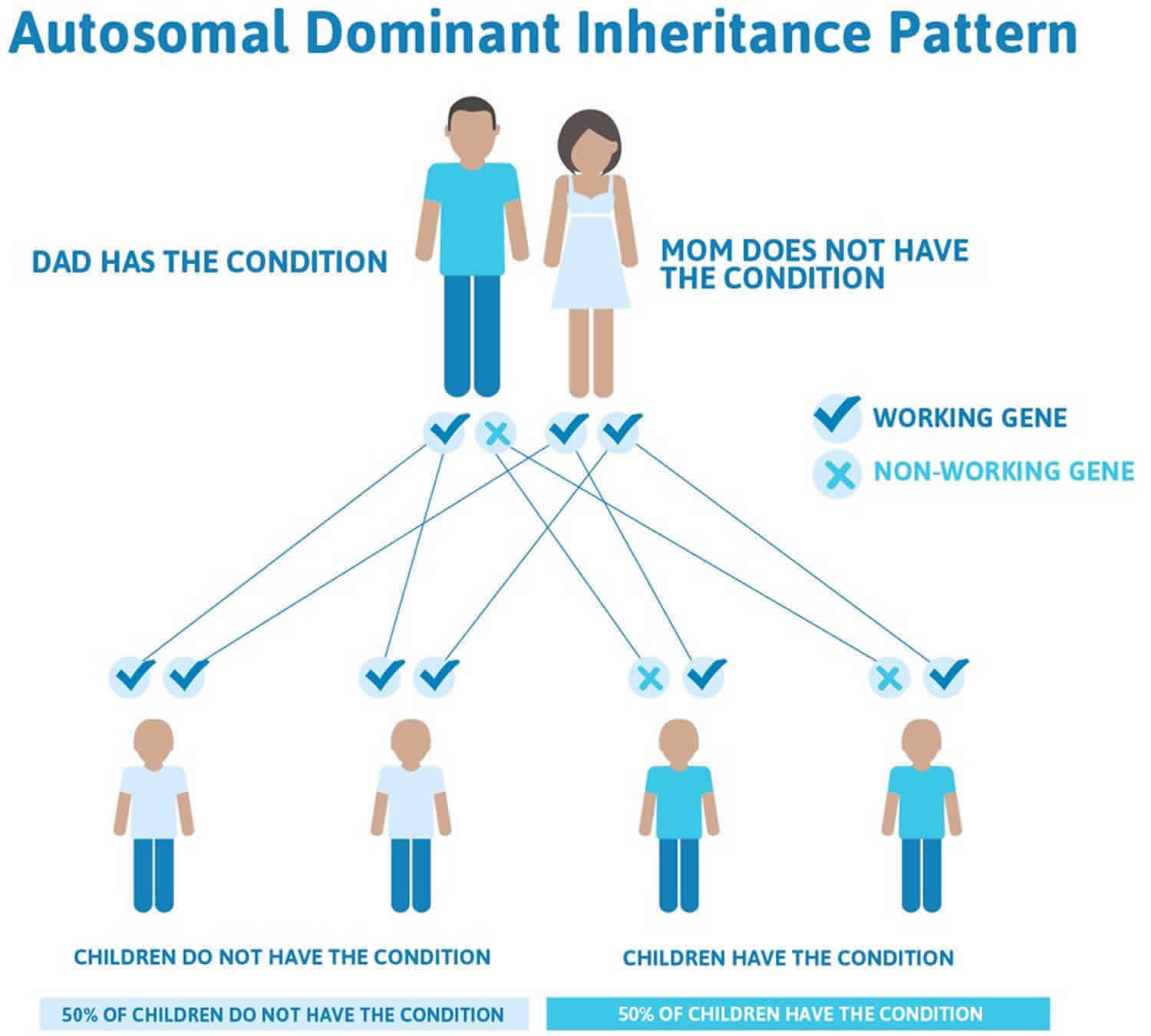

CADASIL inheritance pattern

CADASIL is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, this means that having a mutation in only one copy of the altered NOTCH3 gene in each cell is enough to cause CADASIL. In most cases, an affected person inherits the NOTCH3 gene mutation from one affected parent. The risk of passing the abnormal NOTCH3 gene from affected parent to offspring is 50 percent for each pregnancy. The risk is the same for males and females.

When a person with an autosomal dominant condition has children, each child has a 50% (1 in 2) chance to inherit the mutated copy of the gene.

A few rare cases may result from new mutations (de novo mutations) in the NOTCH3 gene. These cases occur in people with no history of the disorder in their family.

Figure 1. CADASIL autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

CADASIL symptoms

Hallmark symptoms of CADASIL may include:

- Recurrent strokes,

- Cognitive impairment,

- Migraine with aura, and

- Psychiatric disturbances.

These symptoms are caused by damage to small blood vessels, especially those within the brain. The specific symptoms and severity of the disorder can vary greatly among affected individuals, even among members of the same family.

Despite this variability, most individuals (approximately three out of four patients) experience recurrent stroke or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), beginning at 40-50 years of age. Strokes cause weakness and/or loss of feeling of one part of the body, speech difficulties, visual loss or lack of coordination. TIAs (transient ischemic attacks) result in similar symptoms as strokes but resolve in less than 24 hours. Repeated strokes can cause progression of symptoms listed above and also cause cognitive disturbances, loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence) or loss of balance.

Although strokes are the most common symptom associated with CADASIL, some affected individuals never have strokes. It is not uncommon for CADASIL patients to have evidence of stroke on MRI without any history of stroke-like symptoms (silent strokes).

Cognitive impairment eventually develops in many affected individuals on average between the ages of 50-60, although the progression of the disease will vary. Symptoms may include slowly progressive difficulty with concentration, deficits in attention span or memory dysfunction, difficulty making decisions or solving problems, and general loss of interest (apathy). With age, continued cognitive decline may result in dementia, a progressive loss of memory and decline in intellectual abilities that interferes with performing routine tasks of daily life.

Migraine with aura may be a predominant symptom in some affected individuals, occurring in at least half of CADASIL patients. Migraines are severe headaches that often cause excruciating pain and can be disabling. In individuals with CADASIL, abnormal feelings or warning signs called “aura” often precede these headaches. These additional symptoms usually affect vision and may consist of the sudden appearance of a bright light in the center of the field of vision (scintillating scotoma) or, less frequently, disturbances in all or part of the field of vision. The auras preceding the migraine usually last 20 to 30 minutes but are sometimes longer. Some patients suffer from severe attacks with unusual symptoms such as confusion, fever or coma in very rare situations. Finally, many individuals with CADASIL develop psychiatric abnormalities ranging from personality and behavioral changes to severe anxiety and depression.

Migraine

Migraine is often the earliest feature of the disease, being reported in about 55–75% of Caucasian cases, although it is less frequent in Asian populations 8. The age at onset is highly variable, generally around 30 years 9. In a recent article on the prevalence and characteristics of migraine in 378 CADASIL patients 10, a total of 54.5% of individuals had a history of migraine and 84% of these had migraine with aura. Women with migraine with aura accounted for 62.4% of the total, with an earlier migraine with aura onset compared to men. Atypical auras, such as prolonged visual auras, gastrointestinal manifestations, dysarthria, confusion, focal neurologic deficits, and other uncommon manifestations, were experienced by 59.3% of individuals with migraine with aura, and in 19.7% of patients the aura was sine migraine. Migraine with aura was the first clinical manifestation in 41% of symptomatic patients and an isolated symptom in 12.1%. The pathophysiological reasons leading to increased aura prevalence in CADASIL are unknown; a possible mechanism is an increased susceptibility to cortical spreading depression 11. It is also possible that migraine in CADASIL involves the brainstem region. Alternatively, the NOTCH3 mutation itself may act as a migraine with aura susceptibility gene 12.

Subcortical ischemic events

Transient ischemic attacks and stroke are reported in approximately 85% of symptomatic individuals 13 and are related to cerebral small vessel pathology. Mean age at onset of ischemic episodes is approximately 45–50 years 14, but the range at onset is broad (3rd to 8th decade).

Ischemic episodes typically present as a classical lacunar syndrome (pure motor stroke, ataxic hemiparesis/dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome, pure sensory stroke, sensorimotor stroke), but other lacunar syndromes (brain stem or hemispheric) are also observed. The total lacunar lesion load, symptomatic and asymptomatic, is strongly associated with the development of severe disability with gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, pseudobulbar palsy and cognitive impairment. Strokes involving the territory of a large artery have occasionally been reported but whether these are co-incidental or related to the CADASIL pathology itself is uncertain 15. There have been a few cases of subcortical hemorrhage, mostly in patients taking anticoagulants.

Encephalopathy

An acute encephalopathy 16 has been described in 10% of CADASIL patients, and in the majority of these it was the first major symptom, with a mean age of onset of 42 years 17. It is frequently misdiagnosed as encephalitis, particularly if it is the initial presentation in a patient without known CADASIL. It usually evolves from a migraine attack, including confusion, reduced consciousness, seizures, and cortical signs, with spontaneous resolution.

Cognitive impairment in CADASIL first involves information processing speed and executive functions, with relative preservation of episodic memory, and is associated with apathy and depression 18. Memory impairment has been reported, particularly later in the disease. Cognitive screening measures, as the Brief Memory and Executive Test and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, are clinically useful and sensitive screening measures for early cognitive impairment in patients with CADASIL 19; 3-year changes in Mini Mental State Examination, Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, Trail Making Test version B, and modified Rankin Scale are validated models for prediction of clinical course in CADASIL 20. The cognitive deficits were initially attributed to subcortical origin 21. More recently, the cerebral cortex was shown also to be affected in CADASIL 22 by direct mechanisms (cortical microinfarcts) 23 or through secondary degeneration 24. Memory impairment in CADASIL is probably related to different causes, due to both white matter infarcts with disruption of either cortico-cortical or subcortical-cortical networks mainly in the frontal lobe and primary damage of the cortex 25. In a recent longitudinal study, processing speed slowing was related to a decrease of sulcal depth, but not to global brain atrophy or cortical thinning, suggesting that early cognitive changes may be more specifically related to sulcal morphology than to other anatomical changes 26. Moreover, studies in mouse models of CADASIL have detected dysregulation of hippocampal neurogenesis, a process essential for the integration of new spatial memory records 27.

Psychiatric disturbances

Although the clinical expression of the disease is mainly neurological, CADASIL is also characterized by psychiatric disturbances (20–41%) 28. Apathy and major depression are commonly observed in CADASIL. Also bipolar disorder and emotional incontinence are present in a consistent percentage of patients 29. The direct consequence is a negative effect on patient’s quality of life and caregiver burden, with different degrees. Other psychiatric manifestations, such as psychotic disorders, adjustment disorders, personality disorders, drug addiction, and abuse of substances, are less frequent. The pathogenesis of psychiatric disturbances in CADASIL is incompletely understood, but, similarly to other cerebrovascular diseases, may depend on the damage of the cortical–subcortical circuits, leading to the consideration of mood disorders in CADASIL under the concept of ‘vascular depression’.

Reversible acute encephalopathy

Acute encephalopathy has been described in some individuals, with confusion, headache, pyrexia, seizures, and coma, sometimes leading to death 30. Migraine with aura (especially confusional aura) is associated with increased risk of acute encephalopathy, suggesting that they may share pathophysiologic mechanisms 30.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy occurs in 10% of individuals with CADASIL and presents in middle age, usually secondary to stroke 31. In a pooled analysis of previous published cases, three of 105 individuals with CADASIL had a seizure as the initial presenting symptom 32.

Pregnancy

It has been suggested that the risk for migraine with aura is increased during pregnancy, but especially during puerperium (the period between childbirth and the return of the uterus to its normal size) 33. Another study found no association between pregnancy and risk for neurologic events or problems during pregnancy 34.

Other findings

- Cardiac. Controversy exists as to whether CADASIL is associated with cardiac involvement. In a study from The Netherlands, nearly 25% of individuals with CADASIL had a history of acute myocardial infarction and/or current pathologic Q-waves on electrocardiogram (ECG) 35. This percentage was significantly higher than in controls without a heterozygous NOTCH3 pathogenic variant. However, another study of 23 individuals with CADASIL found no signs of previous myocardial infarction on ECG 36. Two studies have suggested an increased risk for arrhythmias, based on increased QT variability on ECG recording 37.

- Nerve. Nerve biopsies may demonstrate signs of axonal damage, demyelination, and ultrastructural changes of the endoneurial blood vessels 38. Punch skin biopsies from individuals with CADASIL showed cutaneous somatic and autonomic nerve involvement 39. Clinically, however, there is no clear evidence that peripheral neuropathy is part of the CADASIL clinical spectrum 40.

- Ocular. Subclinical retinal lesions are reported 41. Fundoscopy may reveal clinically silent retinal vascular abnormalities 42. Optical coherence tomography imaging techniques may show reduced subfoveal choroidal thickness, retinal arterial luminal narrowing, retinal venous luminal enlargement, and reduced vessel density of the deep retinal plexus 43.

- Renal. NOTCH3 accumulation and granular osmophilic material (GOM) are also detected in renal arteries, and stenosis of renal arteries has been described 44. Although no large-scale studies have been published regarding kidney function in individuals with CADASIL, to date there is no evidence that kidney function is affected 45.

CADASIL diagnosis

CADASIL is suspected based on symptoms, family history, and brain MRI lesions compatible with the disease. Although MRI can identify characteristic changes in the brains of individuals with CADASIL, such changes are not unique to CADASIL and can occur with other disorders. As such, the CADASIL diagnosis can only be confirmed by DNA testing of blood samples for characteristic mutations in the NOTCH3 gene or by identifying granular osmiophilic material (GOM) inclusions on a skin biopsy.

CADASIL treatment

At the present, there is no treatment that can cure the disease or prevent its onset. Patients should be treated for factors that can further damage blood vessels, such as hypertension, and should be encouraged to abstain from smoking. The efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) for treatment of acute strokes in CADASIL patients is uncertain; although no contraindication to tPA has been established for this specific population, careful evaluation of prior microbleeds is suggested. Migraines can be treated with traditional analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs. Other medicines commonly used to treat acute migraine attack such as vasoconstrictors: especially triptans or ergot derivates, are not recommended for patients with CADASIL. Medications such as anti-hypertensive, anti-convulsants, and anti-depressants may be used for prevention of migraines in CADASIL patients. Drug therapy for depression or other psychiatric abnormalities are sometimes needed. Psychological support is often essential, and genetic counseling is recommended for affected individuals and their families.

Investigational therapies

The drug donepezil has been evaluated for individuals with CADASIL who have cognitive impairment. In this trial, researchers were not able to establish efficacy of this potential therapy.

L-Arginine was proposed as potential treatment after some benefit was seen on the cerebral circulation in subjects with CADASIL; limitations of the study preclude translating these results to the clinical practice with great accuracy.

CADASIL prognosis

Symptoms of CADASIL usually progress slowly. By age 65, most people have severe cognitive problems and dementia. Some people lose the ability to walk, and most become completely dependent on the care of others due to multiple strokes 46. Life expectancy in people with CADASIL is reduced, mainly because of lung or heart problems 3.

CADASIL life expectancy

Life expectancy is reduced in CADASIL patients. An age at death in men of 64.6 years and in women of 70.7 years has been reported in a large study of 411 subjects 14. Pneumonia in patients with disability was the major cause of death (38%), but a high number of sudden unexpected deaths were also observed, accounting for up to 26% 14. Whether cardiac arrhythmias, QT variability index, and myocardial infarction are more frequent in CADASIL than in the general population remains to be confirmed 47.

Another point of interest is the finding of a non-dipper pattern of nocturnal blood pressure 48. A lower nocturnal blood pressure fall may be associated with incidence and/or worsening of deep white matter lesions in CADASIL. The pathogenesis of abnormal blood pressure profile in CADASIL remains to be clarified. Central and peripheral mechanisms controlling blood pressure variations may be involved.

The association between CADASIL and right-to-left cardiac shunt has been reported but remains under debate 49.

References- CADASIL. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/cadasil

- Hack R, Rutten J, Lesnik Oberstein SAJ. CADASIL. 2000 Mar 15 [Updated 2019 Mar 14]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1500

- Di Donato, I., Bianchi, S., De Stefano, N. et al. Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) as a model of small vessel disease: update on clinical, diagnostic, and management aspects. BMC Med 15, 41 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0778-8

- CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy With Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy). https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1423170-overview

- Familial multiple sclerosis and other inherited disorders of the white matter. Neurologist. 2004 Jul;10(4):201-15. https://journals.lww.com/theneurologist/Abstract/2004/07000/Familial_Multiple_Sclerosis_and_Other_Inherited.4.aspx

- Multiple Sclerosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1146199-overview

- Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, Vahedi K, Chabriat H, Mouton P, et al. Notch3 mutations in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), a Mendelian condition causing stroke and vascular dementia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;826:213–7.

- Kim Y, Choi EJ, Choi CG, Kim G, Choi JH, Yoo HW, et al. Characteristics of CADASIL in Korea: a novel cysteine-sparing Notch3 mutation. Neurology. 2006;66(10):1511–6.

- Tan RY, Markus H. CADASIL: migraine, encephalopathy, stroke and their inter-relationships. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157613

- Guey S, Mawet J, Hervé D, Duering M, Godin O, Jouvent E, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of migraine in CADASIL. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(11):1038–47.

- Eikermann-Haerter K, Yuzawa I, Dilekoz E, Joutel A, Moskowitz MA, Ayata C. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy syndrome mutations increase susceptibility to spreading depression. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):413–8.

- Liem MK, Oberstein SA, van der Grond J, Ferrari MD, Haan J. CADASIL and migraine: a narrative review. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(11):1284–9.

- Dichgans M, Mayer M, Uttner I, Brűning R, Műller-Hőcker J, Rungger G, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of CADASIL: clinical findings in 102 cases. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:731–9.

- Opherk C, Peters N, Herzog J, Luedtke R, Dichgans M. Long-term prognosis and causes of death in CADASIL: a retrospective study in 411 patients. Brain. 2004;127(Pt11):2533–9.

- Yin X, Wu D, Wan J, Yan S, Lou M, Zhao G, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: Phenotypic and mutational spectrum in patients from mainland China. Int J Neurosci. 2015;125(8):585–92.

- Schon F, Martin RJ, Prevett M, Clough C, Enevoldson TP, Markus HS. “CADASIL coma”: an underdiagnosed acute encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 2003;74(2):249–52.

- Adib-Samii P, Brice G, Martin RJ, Markus HS. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL and the effect of cardiovascular risk factors on phenotype: study in 200 consecutively recruited individuals. Stroke. 2010;41(4):630–4.

- Jouvent E, Reyes S, De Guio F, Chabriat H. Reaction time is a marker of early cognitive and behavioural alterations in pure cerebral small vessel disease. J Alzheimer Dis. 2015;47(2):413–9.

- Brookes RL, Hollocks MJ, Tan RY, Morris RG, Markus HS. Brief screening of vascular cognitive impairment in patients with cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy without dementia. Stroke. 2016;47(10):2482–7.

- Jouvent E, Duchesnay E, Hadj-Selem F, De Guio F, Mangin JF, Hervé D, et al. Prediction of 3-year clinical course in CADASIL. Neurology. 2016;87(17):1787–95.

- Romàn GC, Erkinjuntti T, Wallin A, Pantoni L, Chui HC. Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(7):426–36.

- Righart R, Duering M, Gonik M, Jouvent E, Reyes S, Hervé D, et al. Impact of regional cortical and subcortical changes on processing speed in cerebral small vessel disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;2:854–61.

- Jouvent E, Poupon C, Gray F, Paquet C, Mangin JF, Le Bihan D, et al. Intracortical infarcts in small vessel disease: a combined 7-T postmortem MRI and neuropathological case study in cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke. 2011;42(3):e27–30.

- Duering M, Righart R, Csanadi E, Jouvent E, Hervè D, Chabriat H, et al. Incident subcortical infarcts induce focal thinning in connected cortical regions. Neurology. 2012;79(20):2025–8.

- Amberla K, Wäljas M, Tuominen S, Almkvist O, Pőyhőnen M, Tuisku S, et al. Insidious cognitive decline in CADASIL. Stroke. 2004;35(7):1598–602.

- Jouvent E, Mangin JF, Duchesnay E, Porcher R, Düring M, Mewald Y, et al. Longitudinal changes of cortical morphology in CADASIL. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(5):1002. e29–36.

- Ehret F, Vogler S, Pojar S, Elliott DA, Bradke F, Steiner B, et al. Mouse model of CADASIL reveals novel insights into Notch3 function in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;75:131–41.

- Valenti R, Pescini F, Antonini S, Castellini G, Poggesi A, Bianchi S, Inzitari D, Pallanti S, Pantoni L. Major depression and bipolar disorders in CADASIL: a study using the DSM-IV semi-structured interview. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(6):390–5.

- Noh SM, Chung SJ, Kim KK, Kang DW, Lim YM, Kwon SU, et al. Emotional disturbance in CADASIL: its impact on quality of life and caregiver burden. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;37(3):188–94.

- Tan RYY, Markus HS. CADASIL: Migraine, Encephalopathy, Stroke and Their Inter-Relationships. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157613

- Haan J, Lesnik Oberstein SA, Ferrari MD. Epilepsy in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24:316–7.

- Desmond DW, Moroney JT, Lynch T, Chan S, Chin SS, Mohr JP. The natural history of CADASIL: a pooled analysis of previously published cases. Stroke. 1999;30:1230–3.

- Roine S, Poyhonen M, Timonen S, Tuisku S, Marttila R, Sulkava R, Kalimo H, Viitanen M. Neurologic symptoms are common during gestation and puerperium in CADASIL. Neurology. 2005;64:1441–3.

- Donnini I, Rinnoci V, Nannucci S, Valenti R, Pescini F, Mariani G, Bianchi S, Dotti MT, Federico A, Inzitari D, Pantoni L. Pregnancy in CADASIL. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136:668–71.

- Lesnik Oberstein SA, Jukema JW, Van Duinen SG, Macfarlane PW, van Houwelingen HC, Breuning MH, Ferrari MD, Haan J. Myocardial infarction in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:251–6.

- Cumurciuc R, Henry P, Gobron C, Vicaut E, Bousser MG, Chabriat H, Vahedi K. Electrocardiogram in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy patients without any clinical evidence of coronary artery disease: a case-control study. Stroke. 2006b;37:1100–2.

- Piccirillo G, Magrì D, Mitra M, Rufa A, Zicari E, Stromillo ML, De Stefano N, Dotti MT. Increased QT variability in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1216–21.

- Lackovic V, Bajcetic M, Lackovic M, Novakovic I, Labudović Borović M, Pavlovic A, Zidverc-Trajkovic J, Dzolic E, Rovcanin B, Sternic N, Kostic V. Skin and sural nerve biopsies: ultrastructural findings in the first genetically confirmed cases of CADASIL in Serbia. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2012;36:325–35.

- Nolano M, Provitera V, Donadio V, Caporaso G, Stancanelli A, Califano F, Pianese L, Liguori R, Santoro L, Ragno M. Cutaneous sensory and autonomic denervation in CADASIL. Neurology. 2016;86:1039–44.

- Kang SY, Oh JH, Kang JH, Choi JC, Lee JS. Nerve conduction studies in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2009;256:1724–7.

- Cumurciuc R, Massin P, Paques M, Krisovic V, Gaudric A, Bousser MG, Chabriat H. Retinal abnormalities in CADASIL: a retrospective study of 18 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1058–60.

- Pretegiani E, Rosini F, Dotti MT, Bianchi S, Federico A, Rufa A. Visual system involvement in CADASIL. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1377–84.

- Nelis P, Kleffner I, Burg MC, Clemens CR, Alnawaiseh M, Motte J, Marziniak M, Eter N, Alten F. OCT-Angiography reveals reduced vessel density in the deep retinal plexus of CADASIL patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8148

- Lorenzi T, Ragno M, Paolinelli F, Castellucci C, Scarpelli M, Morroni M. CADASIL: Ultrastructural insights into the morphology of granular osmiophilic material. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00624

- Bergmann M, Ebke M, Yuan Y, Brück W, Mugler M, Schwendemann G. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL): a morphological study of a German family. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;92:341–50.

- CADASIL Information Page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Cadasil-Information-Page

- Piccirillo G, Magrì D, Mitra M, Rufa A, Zicari E, Stromillo ML, et al. Increased QT variability in cerebral autosomal dominant artieriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(11):1216–21.

- Rufa A, Dotti MT, Franchi M, Stromillo ML, Cevenini G, Bianchi S, et al. Systemic blood pressure profile in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2554–8.

- Zicari E, Tassi R, Stromillo ML, Pellegrini M, Bianchi S, Cevenini G, et al. Right-to-left shunt in CADASIL patients: prevalence and correlation with clinical and MRI findings. Stroke. 2008;39(7):2155–7.