What is CBD

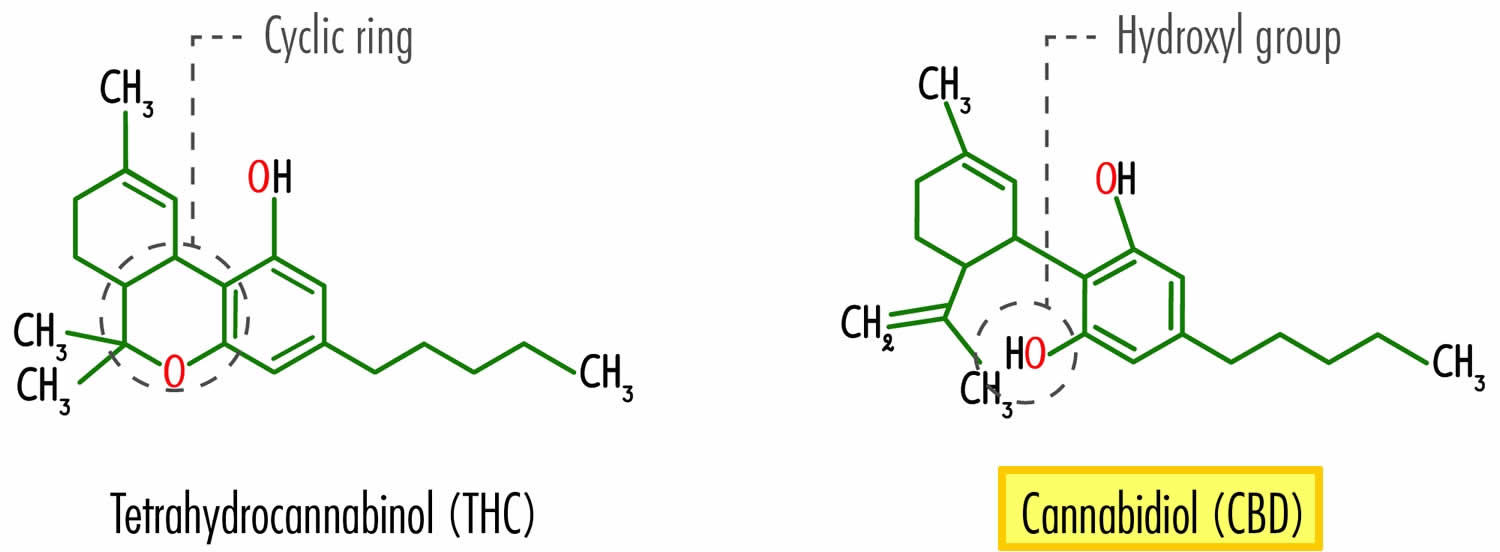

CBD is short for Cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive chemical derived from the Cannabis sativa plant, which is also known as marijuana, ganja or hemp. Cannabis is a plant, and there are two main types, Cannabis Indica and Cannabis Sativa. Both marijuana and CBD can be derived from both types, but hemp is only derived from Cannabis Sativa. By law, hemp must contain no more than 0.3% delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (the oil in marijuana that gives you a high) to be called hemp, otherwise, growers are at risk of prosecution under federal law. Hemp is a great resource for making 100% biodegradable, environmentally friendly products such as clothing, packaging, biofuel, building materials, and paper. Over 100 chemicals, known as cannabinoids or phytocannabinoid compounds, have been identified in the Cannabis sativa plant 1. While delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the major active ingredient in marijuana, cannabidiol (CBD) is also obtained from hemp, which contains only very small amounts of THC. THC is the component that produces the “high” associated with marijuana use. Marijuana is different from CBD. CBD is a single compound in the cannabis plant, and marijuana is a type of cannabis plant or plant material that contains many naturally occurring compounds, including CBD and THC. Unlike THC, CBD does not cause a “high” or euphoric effect because it does not affect the same receptors as THC.

CBD or cannabidiol has attracted significant interest due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and anti-necrotic protective effects, as well as displaying a favorable safety and tolerability profile in humans 2, making it a promising candidate in many therapeutic avenues including epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. GW pharmaceuticals have developed an oral solution of pure CBD (Epidiolex®) for the treatment of two rare and severe treatment-resistant epilepsy syndromes, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome, in patients two years of age and older, showing significant reductions in seizure frequency compared to placebo in several trials 3. Epidiolex® has recently received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval 4 5.

In addition to the federally approved uses of CBD as Epidolex®, CBD usually as CBD oil, is widely used for putative medical benefit in several states, and is certainly used in states in which cannabis has been decriminalized, or legalized, for recreational use 6. There are reports that CBD and other cannabinoids are beneficial for sleep, anxiety, pain, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune-mediated diseases 7. Often these conditions are self-diagnosed and self-treated, so there can be issues with dosing, other drug interactions, and characterization of CBD safety and efficacy.

CBD is also being pursued in clinical trials in Parkinson’s disease, Crohn’s disease, society anxiety disorder, and schizophrenia 8, showing promise in these areas. CBD is also being investigated for its effectiveness in other diseases, including Tuberous Sclerosis, a genetic condition that causes growth of benign tumors all over the body 9, schizophrenia 10 and refractory epileptic encephalopathy 11. Additionally, CBD is widely used as a popular food supplement in a variety of formats for a range of complaints. It is currently illegal to market CBD by adding it to a food or labeling it as a dietary supplement 12. However, some CBD products are being marketed with unproven medical claims and are of unknown quality.

You may have noticed that cannabidiol (CBD) seems to be available almost everywhere, and marketed as a variety of products including drugs, food, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and animal health products. Other than one prescription drug product to treat two rare and severe treatment-resistant epilepsy syndromes, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome, in patients two years of age and older, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any other CBD products, and there is very limited available information about CBD, including about its effects on your body.

CBD products are also being marketed for pets and other animals. The FDA has not approved CBD for any use in animals and the concerns regarding CBD products with unproven medical claims and of unknown quality equally apply to CBD products marketed for animals. The FDA recommends pet owners talk with their veterinarians about appropriate treatment options for their pets.

Despite the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill removing hemp — defined as cannabis and cannabis derivatives with very low concentrations (no more than 0.3% on a dry weight basis) of THC — from the definition of marijuana in the Controlled Substances Act, which made it legal to sell hemp and hemp products in the U.S. CBD products are still subject to the same laws and requirements as FDA-regulated products that contain any other substance. This means that all hemp-derived cannabidiol products are legal. Since cannabidiol has been studied as a new drug, it can’t be legally included in foods or dietary supplements. Also, cannabidiol can’t be included in products marketed with therapeutic claims. Cannabidiol can only be included in “cosmetic” products and only if it contains less than 0.3% THC (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol). But there are still products labeled as dietary supplements on the market that contain cannabidiol. The amount of cannabidiol contained in these products is not always reported accurately on the product label.

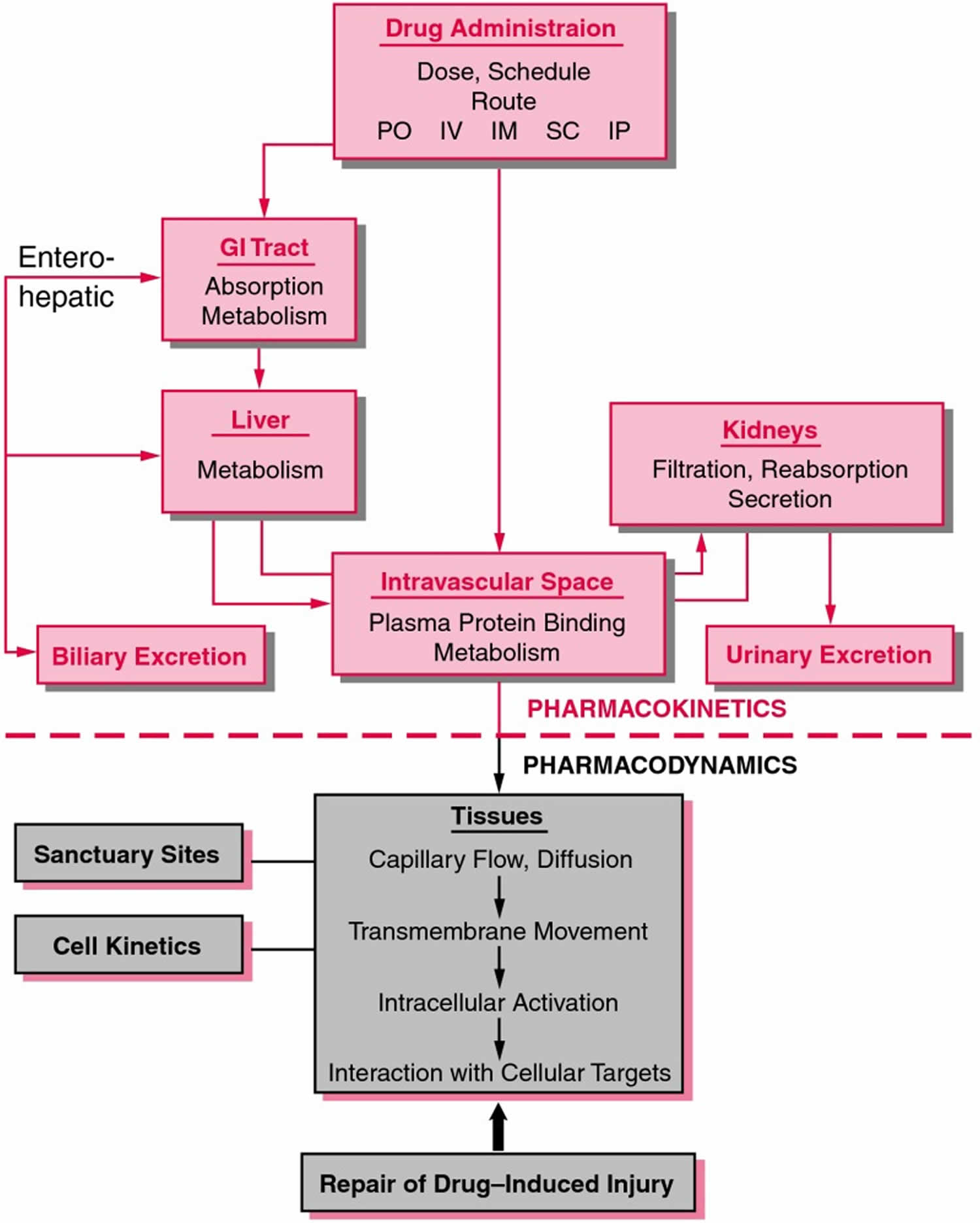

From previous investigations including animal studies, the oral bioavailability of CBD or cannabidiol has been shown to be very low (13–19%) 13. CBD or cannabidiol undergoes extensive first pass metabolism and its metabolites are mostly excreted via the kidneys 14. Plasma and brain concentrations are dose-dependent in animals, and bioavailability is increased with various lipid formulations 15. However, despite the breadth of use of CBD in humans, there is little data on its pharmacokinetics (Figure 2). Pharmacokinetics is the study of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion 16. A fundamental concept in pharmacokinetics is drug clearance, that is, elimination of drugs from the body, analogous to the concept of creatinine clearance. Analysis and understanding of the pharmacokinetics properties of CBD is critical to its future use as a therapeutic compound in a wide range of clinical settings, particularly regarding dosing regimens and routes of administration 17.

Table 1. Medicinal cannabis products

| Name/Material | Constituents/Composition | |

| Cannabis species, including C. sativa | Cannabinoids; also terpenoids and flavonoids | |

| • Hemp (aka industrial hemp) | Low THC (<0.3%); high CBD | |

| • Marijuana/marihuana. Marijuana refers to the dried leaves, flowers, stems, and seeds from the Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica plant. | High THC (>0.3%); low CBD | |

| Nabiximols (trade name: Sativex) | Mixture of ethanol extracts of Cannabis species; contains THC and CBD in a 1:1 ratio | |

| Hemp oil/CBD oil | Solution of a solvent extract from Cannabis flowers and/or leaves dissolved in an edible oil; typically containing 1%–5% CBD | |

| Hemp seed oil | Edible, fatty oil produced from Cannabis seeds; contains no or only traces of cannabinoids | |

| Dronabinol (trade names: Marinol and Syndros) | Synthetic THC | |

| Nabilone (trade names: Cesamet and Canemes) | Synthetic THC analog | |

| Cannabidiol (trade name: Epidiolex) | Highly purified (>98%), plant-derived CBD | |

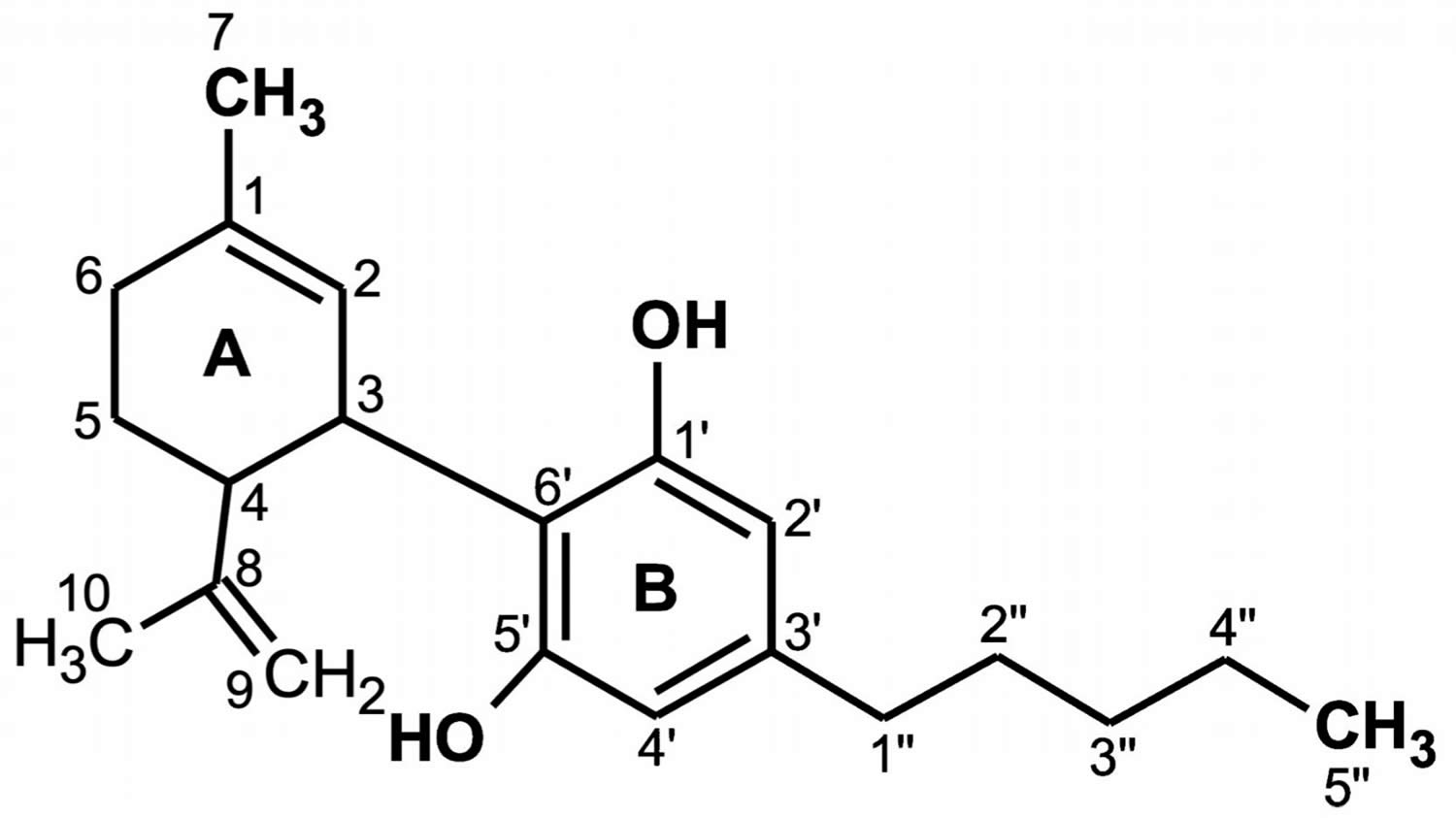

Figure 1. Cannabidiol chemical structure

Footnote: The CBD chemical activity is mainly due to the location and surroundings of the hydroxyl groups in the phenolic ring at the C-1′ and C-5′ positions (B), as well as the methyl group at the C-1 position of the cyclohexene ring (A) and the pentyl chain at the C-3′ of the phenolic ring (B). However, the open CBD ring in the C-4 position is inactive. Due to the hydroxyl groups (C-1′ and C-5′ in the B ring), CBD can also bind to amino acids such as threonine, tyrosine, glutamic acid, or glutamine by means of a hydrogen bond 18.

[Source 19 ]Figure 2. Pharmacokinetics

Footnote: Schematic representation of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacokinetics represents the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of drugs from the body. Pharmacodynamics describes the interaction of drugs with target tissues.

Abbreviations: GI = gastrointestinal; IM = intramuscular; IP = intraperitoneal; IV = intravenous; PO = by mouth; SC = subcutaneous.

[Source 16 ]What is the difference between CBD, cannabis, hemp, marijuana, and THC?

There is still a lot of confusion over what exactly is CBD, with many people thinking cannabis, hemp, marijuana, CBD and THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) are the same thing. They are not.

Cannabis is a plant, and there are two main types; Cannabis Indica and Cannabis Sativa. While marijuana can be derived from both types, hemp is only derived from the Cannabis Sativa family.

This means that even though hemp and marijuana have a few things in common, there are notable differences, with the most crucial being that hemp is almost devoid of THC, which is the chemical in marijuana that gives you a high. In fact, by law, hemp must contain no more than 0.3 percent THC to be considered hemp, otherwise, growers are at risk of prosecution under federal law.

The main active ingredient in hemp is CBD, and CBD does not have any psychoactive properties. Instead, CBD has been credited with relieving anxiety, inflammation, insomnia, and pain, although currently there is little scientific proof that CBD works, except for epilepsy. Epidiolex Is a prescription CBD oil that was FDA approved in June 2018 for two rare and severe forms of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. Other trials are underway investigating the benefits of CBD for Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and anxiety.

In addition to the medicinal uses of CBD, hemp is also a great resource for making 100% biodegradable, environmentally friendly products such as biofuel, building materials, clothing, and paper.

What about hemp seeds?

FDA recently completed an evaluation of some hemp seed-derived food ingredients and had no objections to the use of these ingredients in foods. THC and CBD are found mainly in hemp flowers, leaves, and stems, not in hemp seeds. Hemp seeds can pick up miniscule amounts of THC and CBD from contact with other plant parts, but these amounts are low enough to not raise concerns for any group, including pregnant or breastfeeding mothers.

Does CBD Oil work for pain relief?

Animal studies have shown that CBD has anti-inflammatory effects and works on the endocannabinoid and pain-sensing systems to relieve pain 20. Preliminary studies have shown a favorable effect for CBD for reducing pain; however, more research is needed in the form of larger well-designed trials of longer duration to determine its long-term efficacy and safety.

CBD is thought to work by reducing inflammation in the brain and nervous system via an effect on cannabinoid and other receptors, ion channels, anandamide (a substance that regulates our response to pain) and enzymes.

Unfortunately, few human trials investigating the use of CBD as a single agent to relieve pain exist, with most trials using a combination of CBD and THC to relieve pain. Notably, Health Canada has approved a combination medication that contains both THC and CBD in a 1:1 ratio for the relief of central nerve-related pain in multiple sclerosis, and cancer pain that is unresponsive to optimized opioid therapy.

Sativex® (nabiximols), a combination of THC and CBD as an oromucosal spray, was approved in Canada and the EU for neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis (MS) and intractable cancer pain 21. There are several reasons why combining THC and CBD in a single therapeutic could have value 21. First, additional therapeutic benefit might be gained from hitting multiple targets; for example, if THC alleviates pain and CBD alleviates anxiety, the combination therapy could be quite effective for chronic pain sufferers 22. Second, for disease states in which both THC and CBD are efficacious, a combination might allow for lower doses of THC, thereby potentially decreasing the psychotropic effects of THC. Third, there are some studies suggesting pharmacokinetic interactions between CBD and THC in which CBD treatment increases THC levels, thereby allowing longer duration of effects of THC 23. Sativex® has been evaluated in several clinical trials for spasticity associated with MS, neuropathic pain, and other conditions 24.

An extensive 2018 review on the use of cannabis and cannabidiol products for pain relief stated:

- Cannabinoids do not seem to be equally effective in the treatment of all pain conditions in humans

- Cannabinoids are not effective against acute pain

- Cannabinoids may only modestly reduce chronic pain

- CBD in combination with THC is recommended by the European Federation of Neurological Societies as a second or third-line treatment for central pain in multiple sclerosis, and by Canadian experts as a third-line agent for neuropathic pain

- 22 out of 29 trials investigating cannabis/cannabinoid use for chronic non-cancer pain (neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed chronic pain) found a significant analgesic effect and several reported improvements in other outcomes like sleep or spasticity

- 5 randomized trials showed Cannabis provided >30% reduction in pain scores for people with chronic neuropathic pain (such as that from diabetes, HIV or trauma)

- A Cochrane review found all cannabis-based medicines to be superior to placebo or conventional drugs for neuropathic pain; however, some of these benefits might be outweighed by potential harms such as sedation, confusion, or psychosis. Most products contained THC.

Most studies involved cannabis use or combination CBD/THC products; few studies involved only CBD oil. Many manufacturers of CBD products have based their claims on cannabis studies which have shown a favorable effect; however, it is not apparent whether CBD by itself does have these effects. More trials are needed.

What are CBD gummies?

CBD Gummies are edible candies that contain cannabidiol (CBD) oil. They come in a rainbow of flavors, colors, shapes, and concentrations of CBD. Gummies offer a discreet and easy way to ingest CBD, and effective marketing campaigns by many manufacturers mean their popularity has soared among long-standing CBD users and nonusers alike.

But because most CBD products are not FDA approved, strengths and purity can vary between brands and even within the same brand, meaning that there is no guarantee that you are getting what you think you are getting.

Remember, research into the effectiveness of CBD oil only tested pure CBD oil, not gummies. Even for pure CBD oil, there are very few well-conducted trials backing up its apparent health benefits, although research is expected to ramp up now that laws distinguish between hemp and marijuana.

There is no scientific evidence that gummies work, although anecdotally some people report a benefit and there is likely a strong placebo effect (the act of taking something to relieve your condition makes you feel better even if that product contains nothing).

Be aware that CBD is quite a bitter substance, and a lot of gummies contain large amounts of added sugar to disguise this taste.

Can CBD gummies make you high?

CBD gummies have no psychoactive properties, so they will not give you a high.

CBD is derived from hemp, which is almost devoid of THC. THC is the chemical in marijuana that gives you a high. By law, hemp must contain no more than 0.3 percent THC to be considered hemp, otherwise, growers are at risk of prosecution under federal law.

The main active ingredient in hemp is CBD, and CBD does not have any psychoactive properties. Instead, CBD has been credited with relieving anxiety, inflammation, insomnia, and pain, although “credited” does not mean proven.

Are CBD products legal?

Hemp-derived CBD products that contain less than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) are legal on a federal level; however, they may still be illegal in some states.

Marijuana-derived CBD products are illegal on the federal level; however, may be legal in some states. Check your state laws on CBD products.

What are cannabinoids?

Cannabinoids also known as phytocannabinoids, are are a group of chemicals found in the cannabis plant (Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica) that cause drug-like effects in your body, including the central nervous system and the immune system. Over 100 cannabinoids have been found in Cannabis. The main psychoactive cannabinoid in cannabis is delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Another active cannabinoid is cannabidiol (CBD).

Cannabinoids health benefits

Drugs containing cannabinoids may be helpful in treating certain rare forms of epilepsy, nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, and loss of appetite and weight loss associated with HIV/AIDS. In addition, some evidence suggests modest benefits of cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain and multiple sclerosis symptoms. Cannabis isn’t helpful for glaucoma.

At present, there is insufficient evidence to recommend inhaling cannabis as a treatment for cancer-related symptoms or cancer treatment–related symptoms or cancer treatment-related side effects; however, additional research is needed. Research on cannabis or cannabinoids for other conditions is in its early stages.

Cannabis and cannabinoids health benefits current state of evidence 25:

- There is conclusive or substantial evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are effective:

- For the treatment of chronic pain in adults (cannabis)

- As antiemetics in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (oral cannabinoids)

- For improving patient-reported multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms (oral cannabinoids)

- There is moderate evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are effective for:

- Improving short-term sleep outcomes in individuals with sleep disturbance associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and multiple sclerosis

(cannabinoids, primarily nabiximols)

- Improving short-term sleep outcomes in individuals with sleep disturbance associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and multiple sclerosis

- There is limited evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are effective for:

- Increasing appetite and decreasing weight loss associated with HIV/AIDS (cannabis and oral cannabinoids)

- Improving clinician-measured multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms (oral cannabinoids)

- Improving symptoms of Tourette syndrome (THC capsules)

- Improving anxiety symptoms, as assessed by a public speaking test, in individuals with social anxiety disorders (cannabidiol)

- Improving symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (nabilone; a single, small fair-quality trial)

- There is limited evidence of a statistical association between cannabinoids and:

- Better outcomes (i.e., mortality, disability) after a traumatic brain injury or intracranial hemorrhage

- There is limited evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are ineffective for:

- Improving symptoms associated with dementia (cannabinoids)

- Improving intraocular pressure associated with glaucoma (cannabinoids)

- Reducing depressive symptoms in individuals with chronic pain or multiple sclerosis (nabiximols, dronabinol, and nabilone)

- There is no or insufficient evidence to support or refute the conclusion that cannabis or cannabinoids are an effective treatment for:

- Cancers, including glioma (cannabinoids)

Cancer-associated anorexia cachexia syndrome and anorexia nervosa (cannabinoids) - Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (dronabinol)

- Epilepsy (cannabinoids)

- Spasticity in patients with paralysis due to spinal cord injury (cannabinoids)

- Symptoms associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (cannabinoids)

- Chorea and certain neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with Huntington’s disease (oral cannabinoids)

- Motor system symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease or the levodopa-induced dyskinesia (cannabinoids)

- Dystonia (nabilone and dronabinol)

- Achieving abstinence in the use of addictive substances (cannabinoids)

- Mental health outcomes in individuals with schizophrenia or schizophreniform psychosis (cannabidiol)

- Cancers, including glioma (cannabinoids)

Stimulating appetite

The ability of cannabinoids to increase appetite has been studied:

- Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) taken by mouth: Despite patients’ great interest in oral preparations of cannabis to improve appetite, there is only one trial of cannabis extract used for appetite stimulation. In a randomized controlled trial, researchers compared the safety and effectiveness of orally administered cannabis extract (2.5 mg THC and 1 mg CBD), THC (2.5 mg), or placebo for the treatment of cancer-related anorexia-cachexia in 243 patients with advanced cancer who received treatment twice daily for 6 weeks. Results demonstrated that although these agents were well tolerated by these patients, no differences were observed in patient appetite or quality of life among the three groups at this dose level and duration of intervention 26. A clinical trial compared delta-9-THC (dronabinol) and a standard drug (megestrol, an appetite stimulant) in patients with advanced cancer and loss of appetite 27. Results showed that delta-9-THC did not help increase appetite or weight gain in advanced cancer patients compared with megestrol 27.

- Four controlled trials have assessed the effect of oral THC on measures of appetite, food appreciation, calorie intake, and weight loss in patients with advanced malignancies. Three relatively small, placebo-controlled trials (N = 52; N = 46; N = 65) each found that oral THC produced improvements in one or more of these outcomes 28, 29, 30. The one study that used an active control evaluated the efficacy of dronabinol alone or with megestrol acetate compared with that of megestrol acetate alone for managing cancer-associated anorexia 27. In this randomized, double-blind study of 469 adults with advanced cancer and weight loss, patients received 2.5 mg of oral THC twice daily, 800 mg of oral megestrol daily, or both. Appetite increased by 75% in the megestrol group and weight increased by 11%, compared with a 49% increase in appetite and a 3% increase in weight in the oral THC group after 8 to 11 weeks of treatment. The between-group differences were statistically significant in favor of megestrol acetate. Furthermore, the combined therapy did not offer additional benefits beyond those provided by megestrol acetate alone. The authors concluded that dronabinol did little to promote appetite or weight gain in advanced cancer patients compared with megestrol acetate.

- Inhaled cannabis: There are no published studies of the effect of inhaled cannabis on cancer patients with loss of appetite.

Pain relief

Research has been done on the effects of cannabis or cannabinoids on chronic pain, particularly neuropathic pain (pain associated with nerve injury or damage). A 2018 review looked at 47 studies (4,743 participants) of cannabis or cannabinoids for various types of chronic pain other than cancer pain and found evidence of a small benefit. Twenty-nine percent of people taking cannabis/cannabinoids had a 30 percent reduction in their pain whereas 26 percent of those taking a placebo (an inactive substance) did. The difference may be too small to be meaningful to patients. Adverse events (side effects) were more common among people taking cannabis/cannabinoids than those taking placebos. A 2018 review of 16 studies of cannabis-based medicines for neuropathic pain, most of which tested a cannabinoid preparation called nabiximols (brand name Sativex; a mouth spray containing both THC and CBD that is approved in some countries but not in the United States), found low- to moderate-quality evidence that these medicines produced better pain relief than placebos did. However, the data could not be considered reliable because the studies included small numbers of people and may have been biased. People taking cannabis-based medicines were more likely than those taking placebos to drop out of studies because of side effects. A 2015 review of 28 studies (2,454 participants) of cannabinoids in which chronic pain was assessed found the studies generally showed improvements in pain measures in people taking cannabinoids, but these did not reach statistical significance in most of the studies. However, the average number of patients who reported at least a 30 percent reduction in pain was greater with cannabinoids than with placebo.

- Vaporized cannabis with opioids: In a study of 21 patients with chronic pain, vaporized Cannabis given with morphine relieved pain better than morphine alone, while vaporized Cannabis given with oxycodone did not give greater pain relief. Further studies are needed.

- Inhaled cannabis: Randomized controlled trials of inhaled Cannabis in patients with peripheral neuropathy or other nerve pain found pain was reduced in patients who received inhaled cannabis compared with those who received placebo.

- Cannabis plant extract: A study of Cannabis extract that was sprayed under the tongue found it helped patients with advanced cancer whose pain was not relieved by strong opioids alone. In another study, patients who were given lower doses of cannabinoid spray showed better pain control and less sleep loss than patients who received a placebo. Control of cancer-related pain in some patients was better without the need for higher doses of Cannabis extract spray or higher doses of their other pain medicines. Adverse events were related to high doses of cannabinoid spray.

- Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) taken by mouth: Two small clinical trials of oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) showed that it relieved cancer pain. In the first study, patients had good pain relief, less nausea and vomiting, and better appetite. A second study showed that delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) could relieve pain as well as codeine. An observational study of nabilone also showed that it relieved cancer pain along with nausea, anxiety, and distress when compared with no treatment. However, neither dronabinol nor nabilone is approved by the FDA for pain relief.

A 2015 review of 23 studies (1,326 participants) on the cannabinoids dronabinol or nabilone for treating nausea and vomiting related to cancer chemotherapy found that they were more helpful than a placebo and similar in effectiveness to other medicines used for this purpose. More people had side effects such as dizziness or sleepiness, though, when taking the cannabinoid medicines.

The research on dronabinol and nabilone for treating nausea and vomiting related to cancer chemotherapy was done primarily in the 1980s and 1990s and reflects the types of chemotherapy treatments and choices of anti-nausea medicines available at that time rather than current ones.

Anxiety

Cannabis and cannabinoids have been studied in the treatment of anxiety. A small amount of evidence from studies in people suggests that cannabis or cannabinoids might help to reduce anxiety. One study of 24 people with social anxiety disorder found that they had less anxiety in a simulated public speaking test after taking cannabidiol (CBD) than after taking a placebo. Four studies have suggested that cannabinoids may be helpful for anxiety in people with chronic pain; the study participants did not necessarily have anxiety disorders.

- Inhaled cannabis: A small case series found that patients who inhaled Cannabis had improved mood, improved sense of well-being, and less anxiety. In another study, 74 patients newly diagnosed with head and neck cancer who were cannabis users were matched to 74 nonusers. The cannabis users had markedly lower anxiety or depression and less pain or discomfort than the nonusers. The cannabis users were also less tired, had more appetite, and reported greater feelings of well-being.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Some people with PTSD have used cannabis or products made from it to try to relieve their symptoms and believe that it can help, but there’s been little research on whether it’s actually useful. In one very small study (10 people), the cannabinoid nabilone was more effective than a placebo at relieving PTSD-related nightmares. Observational studies (studies that collected data on people with PTSD who made their own choices about whether to use cannabis) haven’t provided clear evidence on whether cannabis is helpful or harmful for PTSD symptoms.

Sleep problems

Many studies of cannabis or cannabinoids in people with health problems (such as multiple sclerosis, PTSD, or chronic pain) have looked at effects on sleep. Often, there’s been evidence of better sleep quality, fewer sleep disturbances, or decreased time to fall asleep in people taking cannabis/cannabinoids. However, it’s uncertain whether the cannabis products affected sleep directly or whether people slept better because the symptoms of their illnesses had improved. The effects of cannabis/cannabinoids on sleep problems in people who don’t have other illnesses are uncertain.

Helping to decrease opioid use

There’s evidence from studies in animals that administering THC along with opioids may make it possible to control pain with a smaller dose of opioids. A 2017 review looked at studies in people in which cannabinoids were administered along with opioids to treat pain. These studies were designed to determine whether cannabinoids could make it possible to control pain with smaller amounts of opioids. There were 9 studies (750 total participants), of which 3 (642 participants) used a high-quality study design in which participants were randomly assigned to receive cannabinoids or a placebo. The results were inconsistent, and none of the high-quality studies indicated that cannabinoids could lead to decreased opioid use.

Researchers have looked at statistical data on groups of people to see whether access to cannabis (for example, through “medical marijuana laws”—state laws that allow patients with certain medical conditions to get access to cannabis)—is linked with changes in opioid use or with changes in harm associated with opioids. The findings have been inconsistent.

- States with medical marijuana laws were found to have lower prescription rates both for opioids and for all drugs that cannabis could substitute for among people on Medicare. However, data from a national survey (not limited to people on Medicare) showed that users of medical marijuana were more likely than nonusers to report taking prescription drugs.

- An analysis of data from 1999 to 2010 indicated that states with medical marijuana laws had lower death rates from overdoses of opioid pain medicines, but when a similar analysis was extended through 2017, it showed higher death rates from this kind of overdose.

- An analysis of survey data from 2004 to 2014 found that passing of medical marijuana laws was not associated with less nonmedical prescription opioid use. Thus, people with access to medical marijuana did not appear to be substituting it for prescription opioids.

Epilepsy

Cannabinoids, primarily CBD (cannabidiol), have been studied for the treatment of seizures associated with forms of epilepsy that are difficult to control with other medicines. Epidiolex (oral CBD) has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of seizures associated with two epileptic encephalopathies: Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. Epileptic encephalopathies are a group of seizure disorders that start in childhood and involve frequent seizures along with severe impairments in cognitive development. Not enough research has been done on cannabinoids for other, more common forms of epilepsy to allow conclusions to be reached about whether they’re helpful for these conditions.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of diseases that can damage the eye’s optic nerve, leading to vision loss and blindness. Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness in the United States. Glaucoma usually happens when the fluid pressure inside the eyes slowly rises, damaging the optic nerve. Often there are no symptoms at first. Without treatment, people with glaucoma will slowly lose their peripheral, or side vision. They seem to be looking through a tunnel. Over time, straight-ahead vision may decrease until no vision remains. Early treatment can often prevent severe loss of vision. Lowering pressure in the eye can slow progression of the disease.

Studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s showed that cannabis or substances derived from it could lower pressure in the eye, but not as effectively as treatments already in use. One limitation of cannabis-based products is that they only affect pressure in the eye for a short period of time. A recent animal study showed that CBD, applied directly to the eye, may cause an undesirable increase in pressure in the eye.

HIV/AIDS appetite and weight loss symptoms

Unintentional weight loss can be a problem for people with HIV/AIDS. In 1992, the FDA approved the cannabinoid dronabinol for the treatment of loss of appetite associated with weight loss in people with HIV/AIDS. This approval was based primarily on a study of 139 people that assessed effects of dronabinol on appetite and weight changes. There have been a few other studies of cannabis or cannabinoids for appetite and weight loss in people with HIV/AIDS, but they were short and only included small numbers of people, and their results may have been biased. Overall, the evidence that cannabis/cannabinoids are beneficial in people with HIV/AIDS is limited.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease is the name for a group of conditions in which the digestive tract becomes inflamed. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are the most common types. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight loss, and fever. The symptoms can range from mild to severe, and they can come and go, sometimes disappearing for months or years and then returning.

A 2018 review looked at 3 studies (93 total participants) that compared smoked cannabis or cannabis oil with placebos in people with active Crohn’s disease. There was no difference between the cannabis/cannabis oil and placebo groups in clinical remission of the disease. Some people using cannabis or cannabis oil had improvements in symptoms, but some had undesirable side effects. It was uncertain whether the potential benefits of cannabis or cannabis oil were greater than the potential harms.

A 2018 review examined 2 studies (92 participants) that compared smoked cannabis or CBD capsules with placebos in people with active ulcerative colitis. In the CBD study, there was no difference between the two groups in clinical remission, but the people taking CBD had more side effects. In the smoked cannabis study, a measure of disease activity was lower after 8 weeks in the cannabis group; no information on side effects was reported.

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is defined as repeated abdominal pain with changes in bowel movements (diarrhea, constipation, or both). It’s one of a group of functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract that relate to how the brain and gut work together. Although there’s interest in using cannabis/cannabinoids for symptoms of IBS, there’s been little research on their use for this condition in people. Therefore, it’s unknown whether cannabis or cannabinoids can be helpful.

Movement disorders due to Tourette syndrome

A 2015 review of 2 small placebo-controlled studies with 36 participants suggested that synthetic THC capsules may be associated with a significant improvement in tic severity in patients with Tourette syndrome.

Multiple sclerosis

Several cannabis/cannabinoid preparations have been studied for multiple sclerosis symptoms, including dronabinol, nabilone, cannabis extract, nabiximols (brand name Sativex; a mouth spray containing THC and CBD that is approved in more than 25 countries outside the United States), and smoked cannabis. A review of 17 studies of a variety of cannabinoid preparations with 3,161 total participants indicated that cannabinoids caused a small improvement in spasticity (as assessed by the patient), pain, and bladder problems in people with multiple sclerosis, but cannabinoids didn’t significantly improve spasticity when measured by objective tests.

A review of 6 placebo-controlled clinical trials with 1,134 total participants concluded that cannabinoids (nabiximols, dronabinol, and THC/CBD) were associated with a greater average improvement on the Ashworth scale for spasticity in multiple sclerosis patients compared with placebo, although this did not reach statistical significance.

Evidence-based guidelines issued in 2014 by the American Academy of Neurology concluded that nabiximols is probably effective for improving subjective spasticity symptoms, probably ineffective for reducing objective spasticity measures or bladder incontinence, and possibly ineffective for reducing multiple sclerosis–related tremor. Based on two small studies, the guidelines concluded that the data are inadequate to evaluate the effects of smoked cannabis in people with multiple sclerosis.

A 2010 analysis of 3 studies (666 participants) of nabiximols in people with multiple sclerosis and spasticity found that nabiximols reduced subjective spasticity, usually within 3 weeks, and that about one-third of people given nabiximols as an addition to other treatment would have at least a 30 percent improvement in spasticity. Nabiximols appeared to be reasonably safe.

What is cannabis?

Cannabis also known as marijuana, is a plant first grown in Central Asia that is now grown in many parts of the world. Marijuana refers to the dried leaves, flowers, stems, and seeds from the Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica plant. The leaves and flowering tops of cannabis plant contains about 540 chemical substances 31. The cannabis plant makes a resin (thick substance) that contains compounds called cannabinoids, which acts on the endocannabinoid system (see Figure 1 below). The principal cannabinoids appear to be delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabinol (CBN) and cannabidiol (CBD) 32, although the relative abundance of these and other phytocannabinoids can vary depending on a number of factors such as the cannabis strain, the soil and climate conditions, and the cultivation techniques 33. Other phytocannabinoids found in cannabis include cannabigerol (CBG), cannabichromene (CBC), tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) and many others 34. In the living cannabis plant, these phytocannabinoids exist as both inactive monocarboxylic acids (e.g. tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, THCA) and as active decarboxylated forms (e.g. THC); however, heating (at temperatures above 120 °C) promotes decarboxylation (e.g. THCA to THC) 35. Furthermore, pyrolysis (such as by smoking) transforms each of the hundreds of compounds in cannabis into a number of other compounds, many of which remain to be characterized both chemically and pharmacologically. Therefore, cannabis can be considered a very crude drug containing a very large number of chemical and pharmacological constituents, the properties of which are only slowly being understood.

Some cannabinoids are psychoactive (affecting your mind or mood). The use of cannabis and cannabis oil containing specific cannabinoids produces mental and physical effects such as altered sensory perception and euphoria when consumed. Cannabis is a widely used recreational drug which alters sensory perception and causes euphoria 36. Some cannabis plants contain very little THC. Under U.S. law, these plants are considered “industrial hemp” rather than marijuana. The word “marijuana” refers to parts of or products from the plant Cannabis sativa that contain substantial amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). In the United States, cannabis is a controlled substance and has been classified as a Schedule 1 agent (a drug with a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use). By federal law, possessing cannabis (marijuana) is illegal in the United States unless it is used in approved research settings. However, a growing number of states, territories, and the District of Columbia have passed laws to legalize medical marijuana.

Hemp is a mixture of the cannabis plant with very low levels of psychoactive compounds. Hemp oil or cannabidiol (CBD) are products made from extracts of industrial hemp, while hemp seed oil is an edible fatty oil that contains only scant or no cannabinoids. Hemp is not a controlled substance, but CBD is.

Clinical trials that study cannabis for cancer treatment are limited. To do clinical trials research with plant-derived cannabis in the United States, researchers must file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA, have a Schedule 1 license from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and have approval from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

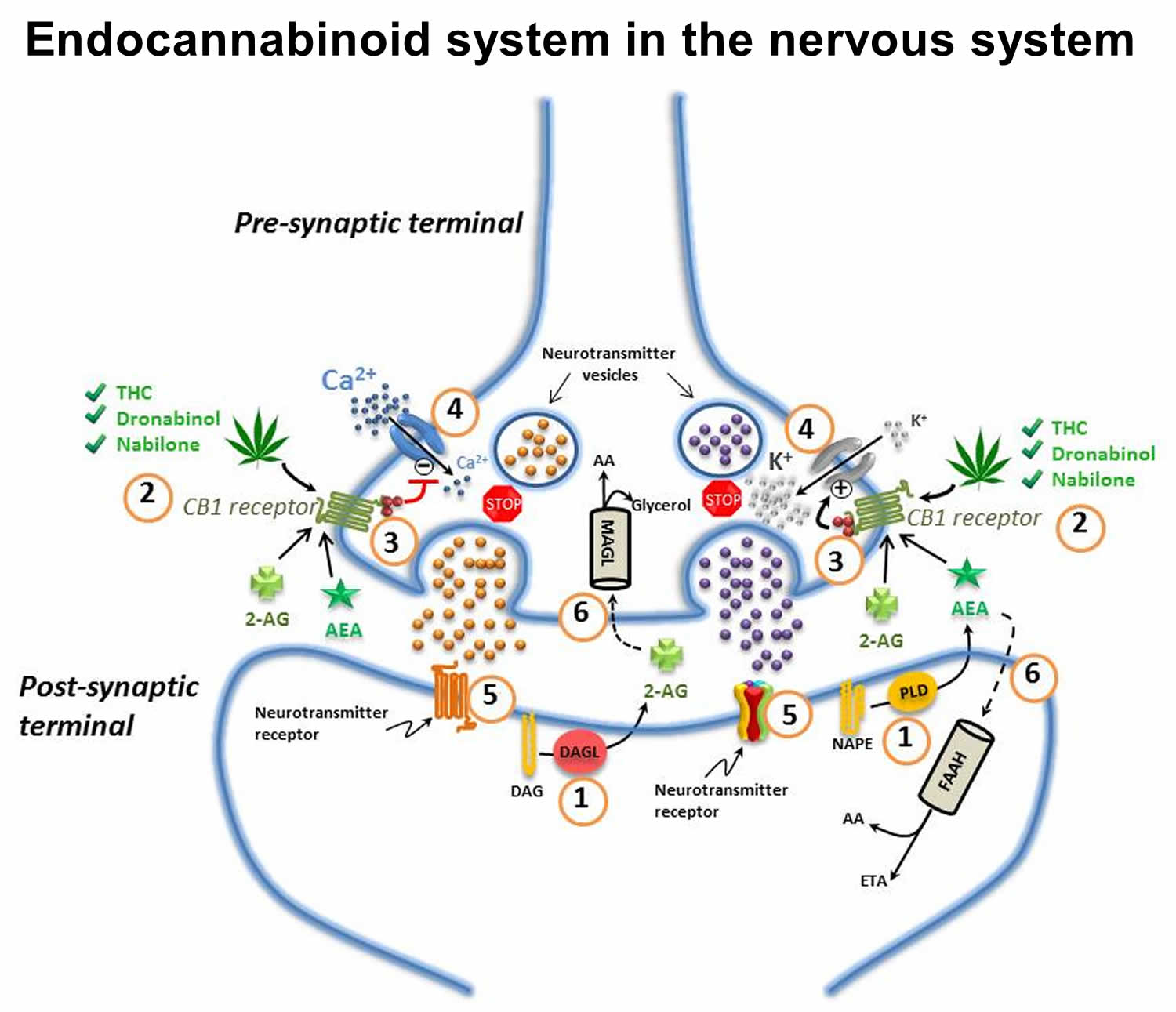

Endocannabinoid system in the nervous system

The endocannabinoid system (Figure 1) is an ancient, evolutionarily conserved, and ubiquitous lipid signaling system found in all vertebrates, and which appears to have important regulatory functions throughout the human body 37. The endocannabinoid system has been implicated in a very broad number of physiological as well as pathophysiological processes including nervous system development, immune function, inflammation, appetite, metabolism and energy, homeostasis, cardiovascular function, digestion, bone development and bone density, synaptic plasticity and learning, pain, reproduction, psychiatric disease, psychomotor behaviour, memory, wake/sleep cycles, and the regulation of stress and emotional state/mood 38, 39, 40. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system contributes to many human diseases including pain, inflammation, psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases 41.

The endocannabinoid system consists mainly of: the cannabinoid 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2) receptors; the cannabinoid receptor ligands N-arachidonoylethanolamine (“anandamide”) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG); the endocannabinoid-synthesizing enzymes N-acyltransferase, phospholipase D, phospholipase C-β and diacylglycerol-lipase (DAGL); and the endocannabinoid-degrading enzymes fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) (Figure 1) 38. Anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are considered the primary endogenous activators of cannabinoid signaling, but other endogenous molecules, which exert “cannabinoid-like” effects, have also been described. These other molecules include 2-arachidonoylglycerol ether (noladin ether), N -arachidonoyl-dopamine, virodhamine, N -homo-γ-linolenoylethanolamine and N-docosatetraenoylethanolamine 38. Other molecules such as palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) and oleoylethanolamide (OEA) do not appear to bind to cannabinoid receptors but rather to a specific isozyme belonging to a class of nuclear receptors/transcription factors known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) 42. These fatty acyl ethanolamides may, however, potentiate the effect of anandamide by competitive inhibition of FAAH, and/or through direct allosteric effects on other receptors such as the transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV1) channel 43. This type of effect has been generally referred to as the so-called “entourage effect” 43. The term “entourage effect” is also used in the context of the interactions between phytocannabinoids and terpenes in a physiological system.

Most tissues contain a functional endocannabinoid system with the CB1 and CB2 receptors having distinct patterns of tissue expression. The CB1 receptor is one of the most abundant G-protein coupled receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems 44. It has been detected in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, basal ganglia, substantia nigra pars reticulata, internal and external segments of the globus pallidus and cerebellum (molecular layer), and at central and peripheral levels of the pain pathways including the periaqueductal gray matter, the rostral ventrolateral medulla, the dorsal primary afferent spinal cord regions including peripheral nociceptors, and spinal interneurons 45. CB1 receptor density is highest in the cingulate gyrus, the frontal cortex, the hippocampus, the cerebellum, and the basal ganglia 41. Moderate levels of CB1 receptor expression are found in the basal forebrain, amygdala, nucleus accumbens, periaqueductal grey, and hypothalamus and much lower expression levels of the receptor are found in the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla/brainstem 41. Relatively little CB1 receptor expression is found in the thalamus and the primary motor cortex 41. The CB1 receptor is also expressed in many other organs and tissues including adipocytes, leukocytes, spleen, heart, lung, the gastrointestinal tract (liver, pancreas, stomach, and the small and large intestine), kidney, bladder, reproductive organs, skeletal muscle, bone, joints, and skin 46. CB2 receptors are most highly concentrated in the tissues and cells of the immune system such as the leukocytes and the spleen, but can also be found in bone and to a lesser degree in liver and in nerve cells including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia, and even some neuronal sub-populations 47.

Besides the well-known CB1 and CB2 receptors, a number of different cannabinoids are believed to bind to a number of other molecular targets. Such targets include the third putative cannabinoid receptor GPR55 (G protein-coupled receptor 55), the transient receptor potential (TRP) cation channel family, and a class of nuclear receptors/transcription factors known as the PPARs, as well as 5-HT1A receptors, the α2 adrenoceptors, adenosine and glycine receptors 48. Modulation of these other cannabinoid targets adds additional layers of complexity to the known myriad effects of cannabinoids.

Dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system appears to be connected to a number of pathological conditions, with the changes in the functioning of the system being either protective or harmful 49. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system either through the targeted inhibition of specific metabolic pathways, and/or directed agonism or antagonism of its receptors may hold therapeutic promise 50. However, a major and consistent therapeutic challenge confronting the routine use of (THC-predominant) cannabis and psychoactive cannabinoids (e.g. THC) in the clinic has remained that of achieving selective targeting of the site of disease or symptoms and the sparing of other bodily regions such as the mood and cognitive centers of the brain 45. Despite this significant challenge, emerging evidence from clinical studies of smoked or vaporized (THC-predominant) cannabis for chronic non-cancer pain (mainly neuropathic pain) suggests that use of very low doses of THC (< 3 mg/dose) may confer therapeutic benefits with minimal psychoactive side effects 51.

Figure 3. Endocannabinoid system in the nervous system

Footnotes: (1) Endocannabinoids are manufactured “on-demand” (e.g. in response to an action potential in neurons) in the post-synaptic terminals: anandamide (AEA) is generated from phospholipase-D (PLD)-mediated hydrolysis of the membrane lipid N-arachidonoylphosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE); 2-AG from the diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL)-mediated hydrolysis of the membrane lipid diacylglycerol (DAG); (2) These endocannabinoids [anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)] diffuse retrogradely towards the pre-synaptic terminals and like exogenous cannabinoids such as THC (from cannabis), dronabinol, and nabilone, they bind to and activate the pre-synaptic G-protein-coupled CB1 receptors; (3) Binding of phytocannabinoid and endocannabinoid agonists to the CB1 receptors triggers Gi/Go protein signalling that, for example, inhibits adenylyl cyclase, thus decreasing the formation of cyclic AMP and the activity of protein kinase A; (4) Activation of the CB1 receptor also results in Gi/Go protein-dependent opening of inwardly-rectifying K+ channels (depicted with a “+”) causing a hyperpolarization of the pre-synaptic terminals, and the closing of Ca2+ channels (depicted with a “-“), arresting the release of stored excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters (e.g. glutamate, GABA, 5-HT, acetylcholine, noradrenaline, dopamine, D-aspartate and cholecystokinin) which (5) once released, diffuse and bind to post-synaptic receptors; (6) Anandamide and 2-AG re-enter the post- or pre-synaptic nerve terminals (possibly through the actions of a specialized transporter depicted by a “dashed” line) where they are respectively catabolized by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) or monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) to yield either arachidonic acid (AA) and ethanolamine (ETA), or arachidonic acid (AA) and glycerol.

Endocannabinoid signaling is rapidly terminated by the action of two hydrolytic enzymes: fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) 39. FAAH is primarily localized post-synaptically 52 and preferentially degrades anandamide 53; MAGL is primarily localized pre-synaptically 52 and favors the catabolism of 2-AG 53. Signal termination is important in ensuring that biological activities are properly regulated and prolonged signaling activity, such as by the use of cannabis, can have potentially deleterious effects 54.

[Source 55 ]Cannabis pharmacology

When oral cannabis is ingested, there is a low (6%–20%) and variable oral bioavailability 56. Peak plasma concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) occur after 1 to 6 hours and remain elevated with a terminal half-life of 20 to 30 hours. Taken by mouth, delta-9-THC is initially metabolized in the liver to 11-OH-THC (11-hydroxy-delta-tetrahydrocannabinol), a potent psychoactive metabolite. Inhaled cannabinoids are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream with a peak concentration in 2 to 10 minutes, declining rapidly for a period of 30 minutes and with less generation of the psychoactive 11-OH-THC metabolite.

Cannabinoids are known to interact with the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme system 57. In one study 58, 24 cancer patients were treated with intravenous irinotecan (600 mg, n = 12) or docetaxel (180 mg, n = 12), followed 3 weeks later by the same drugs concomitant with medicinal cannabis taken in the form of an herbal tea for 15 consecutive days, starting 12 days before the second treatment. The administration of cannabis did not significantly influence exposure to and clearance of irinotecan or docetaxel, although the herbal tea route of administration may not reproduce the effects of inhalation or oral ingestion of fat-soluble cannabinoids.

How does cannabidiol or CBD work?

Cannabidiol or CBD is one of the main pharmacologically active phytocannabinoids 59. CBD has a wide spectrum of biological activity, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity 60, which is why its activity in the prevention and treatment of diseases whose development is associated with oxidation-reduction (redox) imbalance and inflammation has been tested 61. An oxidation-reduction (redox) reaction is a type of chemical reaction that involves a transfer of electrons between two species. An oxidation-reduction oxidation-reduction (redox) reaction is any chemical reaction in which the oxidation number of a molecule, atom, or ion changes by gaining or losing an electron. Based on the current research results, the possibility of using CBD for the treatment of diabetes, diabetes-related cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular diseases (including stroke, arrhythmia, atherosclerosis, and hypertension), cancer, arthritis, anxiety, psychosis, epilepsy, neurodegenerative disease (i.e., Alzheimer’s) and skin disease is being considered 62. Analysis of CBD antioxidant activity showed that it can regulate the state of redox directly by affecting the components of the redox system and indirectly by interacting with other molecular targets associated with redox system components.

In addition, cannabidiol or CBD has effects on the brain with anxiolytic, antidepressant, antipsychotic, and anticonvulsant properties, among others 63. The exact cause for these effects is not clear. However, cannabidiol seems to prevent the breakdown of a chemical in the brain that affects pain, mood, and mental function. Preventing the breakdown of this chemical and increasing its levels in the blood seems to reduce psychotic symptoms associated with conditions such as schizophrenia. Cannabidiol might also block some of the psychoactive effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Also, cannabidiol seems to reduce pain and anxiety.

How effective is Cannabidiol?

The effectiveness ratings for Cannabidiol or CBD are as follows:

Cannabidiol or CBD is likely effective for

- Seizure disorder (epilepsy). A specific cannabidiol product (Epidiolex, GW Pharmaceuticals) has been shown to reduce seizures in adults and children with various conditions that are linked with seizures. This product is a prescription drug for treating seizures caused by Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, or tuberous sclerosis complex. It has also been shown to reduce seizures in people with Sturge-Weber syndrome, febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), and specific genetic disorders that cause epileptic encephalopathy. But it’s not approved for treating these other types of seizures. This product is usually taken in combination with conventional anti-seizure medicines. Some cannabidiol products that are made in a lab are also being studied for epilepsy. But research is limited, and none of these products are approved as prescription drugs.

Cannabidiol or CBD has insufficient evidence to rate effectiveness for

- Bipolar disorder. Early reports show that taking cannabidiol does not improve manic episodes in people with bipolar disorders.

- Depression. Animal studies have shown some effect of CBD at relieving depression, possibly related to its strong anti-stress effect after either acute or repeated administration 64. Animal studies have shown that CBD has a positive effect on serotonin levels in the brain, and serotonin. Low levels of serotonin are thought to play a key role in mood as well as pain 65. CBD may help with depression but more trials are needed.

- A type of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn disease). Early research shows that taking cannabidiol does not reduce disease activity in adults with Crohn disease.

- Diabetes. Early research shows that taking cannabidiol does not improve blood glucose levels, blood insulin levels, or HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes.

- A movement disorder marked by involuntary muscle contractions (dystonia). Early research suggests that taking cannabidiol daily for 6 weeks might improve dystonia by 20% to 50% in some people. Higher quality research is needed to confirm this.

- An inherited condition marked by learning disabilities (fragile- X syndrome). Early research found that applying cannabidiol gel might reduce anxiety and improve behavior in patients with fragile X syndrome.

- A condition in which a transplant attacks the body (graft-versus-host disease or GVHD). Graft-versus-host disease is a complication that can occur after a bone marrow transplant. In people with this condition, donor cells attack the person’s own cells. Early research shows that taking cannabidiol daily starting 7 days before bone marrow transplant and continuing for 30 days after transplant can extend the time it takes for a person to develop GVHD.

- An inherited brain disorder that affects movements, emotions, and thinking (Huntington disease). Early research shows that taking cannabidiol daily does not improve symptoms of Huntington’s disease.

- Insomnia. Early research suggests that taking 160 mg of cannabidiol before bed improves sleep time in people with insomnia. However, lower doses do not have this effect. Cannabidiol also does not seem to help people fall asleep and might reduce the ability to recall dreams.

- Multiple sclerosis (MS). There is inconsistent evidence on the effectiveness of cannabidiol for symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Some early research suggests that using a cannabidiol spray under the tongue might improve pain and muscle tightness in people with MS. However, it does not appear to improve muscle spasms, tiredness, bladder control, the ability to move around, or well-being and quality of life.

- Withdrawal from heroin, morphine, and other opioid drugs. Early research shows that taking cannabidiol for 3 days reduces cravings and anxiety in people with heroin use disorder that are not using heroin or any other opioid drugs.

- Parkinson disease. Early research shows that taking a single dose of cannabidiol can reduce anxiety during public speaking in people with Parkinson disease. Other early research shows that taking cannabidiol daily for 4 weeks improves psychotic symptoms in people with Parkinson disease and psychosis. For most studies, there were no differences across groups with regards to movement-related outcomes; however, groups treated with CBD 300 mg/day had a significantly improved well-being and quality of life as measured by the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire [PDQ-39]). CBD shows promise for improving the quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease but larger trials are needed.

- Schizophrenia. Research on the use of cannabidiol for psychotic symptoms in people with schizophrenia is conflicting. Some early research suggests that taking cannabidiol four times daily for 4 weeks improves psychotic symptoms and might be as effective as the antipsychotic medication amisulpride. However, other early research suggests that taking cannabidiol for 14 days is not beneficial. The conflicting results might be related to the cannabidiol dose used and duration of treatment.

- Quitting smoking. Early research suggests that inhaling cannabidiol with an inhaler for one week might reduce the number of cigarettes smoked by about 40% compared to baseline.

- A type of anxiety marked by fear in some or all social settings (social anxiety disorder). Some early research shows that taking cannabidiol 300 mg daily does not improve anxiety during public speaking in people with social anxiety disorder. But it might help with public speaking in people who don’t have social anxiety disorder. It might also help with general social anxiety. Also, some research suggests that taking a higher dose (400-600 mg) may improve anxiety associated with public speaking or medical imaging testing.

- A group of painful conditions that affect the jaw joint and muscle (temporomandibular disorders or TMD). Early research shows that applying an oil containing cannabidiol to the skin might improve nerve function in people with temporomandibular disorders.

- Nerve damage in the hands and feet (peripheral neuropathy).

- Nausea and vomiting. Most studies investigating if CBD is beneficial at relieving nausea or vomiting, have used a combination of CBD and THC, rather than just CBD alone. A 2016 review 66 found the combination to be either more effective or as effective as a placebo. More recent research points to THC being more effective at reducing nausea and vomiting than CBD. CBD is unlikely to be effective by itself for nausea and vomiting. The combination of THC and CBD does seem to be effective for nausea and vomiting.

- Arthritis. Animal studies showed that topical CBD applications relieve pain and inflammation associated with arthritis with few side effects. The topical application of CBD is beneficial because CBD is poorly absorbed when taken by mouth and can cause gastrointestinal side effects 67. Topical CBD may be beneficial at relieving arthritis but no high-quality human studies prove this.

- Other conditions.

More evidence is needed to rate the effectiveness of cannabidiol for these uses.

Is Cannabidiol or CBD safe?

- When taken by mouth: Cannabidiol (CBD) is POSSIBLY SAFE when taken by mouth or sprayed under the tongue appropriately. Cannabidiol in doses of up to 300 mg daily have been taken by mouth safely for up to 6 months. Higher doses of 1200-1500 mg daily have been taken by mouth safely for up to 4 weeks. A prescription cannabidiol product (Epidiolex) is approved to be taken by mouth in doses of up to 25 mg/kg daily. Cannabidiol sprays that are applied under the tongue have been used in doses of 2.5 mg for up to 2 weeks.

- Some reported side effects of cannabidiol include dry mouth, low blood pressure, light headedness, and drowsiness. Signs of liver injury have also been reported in some patients, but this is less common.

- When applied to the skin: There isn’t enough reliable information to know if cannabidiol is safe or what the side effects might be.

You should not use cannabidiol or CBD if you are allergic to cannabidiol or sesame seed oil.

Cannabidiol is not approved for use by anyone younger than 2 years old.

Tell your doctor if you have ever had:

- liver disease;

- drug or alcohol addiction;

- depression, a mood disorder; or

- suicidal thoughts or actions.

Some people have thoughts about suicide while taking cannabidiol. Your doctor will need to check your progress at regular visits. Your family or other caregivers should also be alert to changes in your mood or symptoms.

Tell your doctor if you are pregnant or breastfeeding.

If you are pregnant, your name may be listed on a pregnancy registry to track the effects of cannabidiol on the baby.

Consumers should be aware of the potential risks associated with using cannabidiol or CBD products. Some of these can occur without your awareness, such as:

- Liver injury: During its review of the marketing application for Epidiolex — a purified form of CBD that the FDA approved in 2018 for use in the treatment of two rare and severe seizure disorders — the FDA identified certain safety risks, including the potential for liver injury. This serious risk can be managed when an FDA-approved CBD drug product is taken under medical supervision, but it is less clear how it might be managed when CBD is used far more widely, without medical supervision, and not in accordance with FDA-approved labeling. Although this risk was increased when taken with other drugs that impact the liver, signs of liver injury were seen also in patients not on those drugs. The occurrence of this liver injury was identified through blood tests, as is often the case with early problems with the liver. Liver injury was also seen in other studies of CBD in published literature. We are concerned about potential liver injury associated with CBD use that could go undetected if not monitored by a healthcare provider.

- Drug interactions: Information from studies of the FDA-approved CBD drug Epidiolex show that there is a risk of CBD impacting other medicines you take – or that other medicines you take could impact the dose of CBD that can safely be used. Taking CBD with other medications may increase or decrease the effects of the other medications. This may lead to an increased chance of adverse effects from, or decreased effectiveness of, the other medications. Drug interactions were also seen in other studies of CBD in published literature. We are concerned about the potential safety of taking other medicines with CBD when not being monitored by a healthcare provider. In addition, there is limited research on the interactions between CBD products and herbs or other plant-based products in dietary supplements. Consumers should use caution when combining CBD products with herbs or dietary supplements.

- Male Reproductive Toxicity: Studies in laboratory animals showed male reproductive toxicity, including in the male offspring of CBD-treated pregnant females. The changes seen include decrease in testicular size, inhibition of sperm growth and development, and decreased circulating testosterone, among others. Because these findings were only seen in animals, it is not yet clear what these findings mean for human patients and the impact it could have on men (or the male children of pregnant women) who take CBD. For instance, these findings raise the concern that CBD could negatively affect a man’s fertility. Further testing and evaluation are needed to better understand this potential risk.

In addition, CBD can be the cause of side effects that you might notice. These side effects should improve when CBD is stopped or when the amount used is reduced. This could include changes in alertness, most commonly experienced as somnolence (sleepiness), but this could also include insomnia; gastrointestinal distress, most commonly experienced as diarrhea and/or decreased appetite but could also include abdominal pain or upset stomach; and changes in mood, most commonly experienced as irritability and agitation.

The FDA is actively working to learn more about the safety of CBD and CBD products, including the risks identified above and other topics, such as:

- Cumulative Exposure: The cumulative exposure to CBD if people access it across a broad range of consumer products. For example, what happens if you eat food with CBD in it, use CBD-infused skin cream and take other CBD-based products on the same day? How much CBD is absorbed from your skin cream? What if you use these products daily for a week or a month?

- Special Populations: The effects of CBD on other special populations (e.g., the elderly, children, adolescents, pregnant and lactating women).

- CBD and Animals: The safety of CBD use in pets and other animals, including considerations of species, breed, or class and the safety of the resulting human food products (e.g., meat milk, or eggs) from food-producing species.

Cannabidiol or CBD potential harm, side effects and unknowns

There are still many unanswered questions about the science, safety, and quality of products containing CBD.

- Cannabidiol or CBD has the potential to harm you and harm can happen even before you become aware of it.

- CBD can cause liver injury.

- CBD can affect how other drugs you are taking work, potentially causing serious side effects.

- Use of CBD with alcohol or other drugs that slow brain activity, such as those used to treat anxiety, panic, stress, or sleep disorders, increases the risk of sedation and drowsiness, which can lead to injuries.

- Male reproductive toxicity, or damage to fertility in males or male offspring of women who have been exposed, has been reported in studies of animals exposed to CBD.

- CBD can cause side effects that you might notice. These side effects should improve when CBD is stopped or when the amount used is reduced.

- Changes in alertness, most commonly experienced as somnolence (drowsiness or sleepiness).

- Gastrointestinal distress, most commonly experienced as diarrhea and/or decreased appetite.

- Changes in mood, most commonly experienced as irritability and agitation.

- There are many important aspects about CBD that scientists just don’t know, such as:

- What happens if you take CBD daily for sustained periods of time?

- What level of intake triggers the known risks associated with CBD?

- How do different methods of consumption affect intake (e.g., oral consumption, topical , smoking or vaping)?

- What is the effect of CBD on the developing brain (such as on children who take CBD)?

- What are the effects of CBD on the developing fetus or breastfed newborn?

- How does CBD interact with herbs and other plant materials?

- Does CBD cause male reproductive toxicity in humans, as has been reported in studies of animals?

Special precautions and warnings for Cannabidiol or CBD

- Pregnancy and breast-feeding: Cannabidiol or CBD is POSSIBLY UNSAFE to use if you are pregnant or breast feeding. Cannabidiol products can be contaminated with other ingredients that may be harmful to the fetus or infant. Stay on the safe side and avoid use.

- Children: A prescription cannabidiol product (Epidiolex) is POSSIBLY SAFE when taken by mouth in doses up to 25 mg/kg daily. This product is approved for use in certain children 1 year of age and older.

- Liver disease: People with liver disease may need to use lower doses of cannabidiol compared to healthy patients.

- Parkinson disease: Some early research suggests that taking high doses of cannabidiol might make muscle movement and tremors worse in people with Parkinson disease.

Cannabidiol or CBD interactions with medications

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions – be cautious with this combination.

- Brivaracetam (Briviact): Brivaracetam is changed and broken down by the body. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the body breaks down brivaracetam. This might increase levels of brivaracetam in the body.

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol): Carbamazepine is changed and broken down by the body. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the body breaks down carbamazepine. This might increase levels of carbamazepine in the body and increase its side effects.

- Clobazam (Onfi): Clobazam is changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down clobazam. This might increase the effects and side effects of clobazam.

- Eslicarbazepine (Aptiom): Eslicarbazepine is changed and broken down by the body. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the body breaks down eslicarbazepine. This might increase levels of eslicarbazepine in the body by a small amount.

- Everolimus (Zostress): Everolimus is changed and broken down by the body. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the body breaks down everolimus. This might increase levels of everolimus in the body.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include chlorzoxazone (Lorzone) and theophylline (Theo-Dur, others).

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include amitriptyline (Elavil), haloperidol (Haldol), ondansetron (Zofran), propranolol (Inderal), theophylline (Theo-Dur, others), verapamil (Calan, Isoptin, others), and others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include theophylline (Theo-Dur, others), omeprazole (Prilosec, Omesec), clozapine (Clozaril, FazaClo), progesterone (Prometrium, others), lansoprazole (Prevacid), flutamide (Eulexin), oxaliplatin (Eloxatin), erlotinib (Tarceva), and caffeine.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2A6 (CYP2A6) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include nicotine, chlormethiazole (Heminevrin), coumarin, methoxyflurane (Penthrox), halothane (Fluothane), valproic acid (Depacon), disulfiram (Antabuse), and others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include ketamine (Ketalar), phenobarbital, orphenadrine (Norflex), secobarbital (Seconal), and dexamethasone (Decadron).

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include proton pump inhibitors including omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), and pantoprazole (Protonix); diazepam (Valium); carisoprodol (Soma); nelfinavir (Viracept); and others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2C8 (CYP2C8) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include amiodarone (Cordarone), carbamazepine (Tegretol), chloroquine (Aralen), diclofenac (Voltaren), paclitaxel (Taxol), repaglinide (Prandin) and others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac (Cataflam, Voltaren), ibuprofen (Motrin), meloxicam (Mobic), piroxicam (Feldene), and celecoxib (Celebrex); amitriptyline (Elavil); warfarin (Coumadin); glipizide (Glucotrol); losartan (Cozaar); and others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include amitriptyline (Elavil), codeine, desipramine (Norpramin), flecainide (Tambocor), haloperidol (Haldol), imipramine (Tofranil), metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol XL), ondansetron (Zofran), paroxetine (Paxil), risperidone (Risperdal), tramadol (Ultram), venlafaxine (Effexor), and others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

- Some medications changed by the liver include alprazolam (Xanax), amlodipine (Norvasc), clarithromycin (Biaxin), cyclosporine (Sandimmune), erythromycin, lovastatin (Mevacor), ketoconazole (Nizoral), itraconazole (Sporanox), fexofenadine (Allegra), triazolam (Halcion), verapamil (Calan, Isoptin) and many others.

Cannabidiol or CBD moderate interactions by medications that are changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Cannabidiol might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. In theory, using cannabidiol along with some medications that are broken down by the liver might increase the effects and side effects of some medications. Before using cannabidiol, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.