Human ear

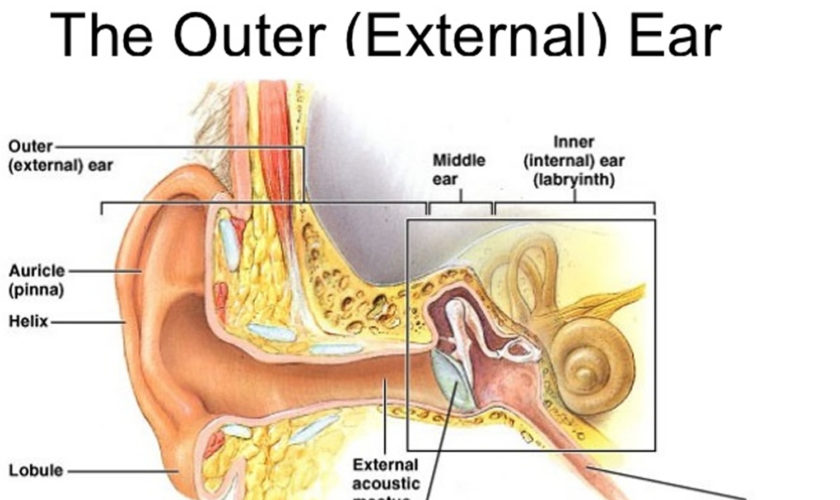

The ear is divided into three anatomical regions: the external ear, the middle ear, and the internal ear (Figure 2). The external ear is the visible portion of the ear, and it collects and directs sound waves to the eardrum. The middle ear is a chamber located within the petrous portion of the temporal bone. Structures within the middle ear amplify sound waves and transmit them to an appropriate portion of the internal ear. The internal ear contains the sensory organs for equilibrium (balance) and hearing.

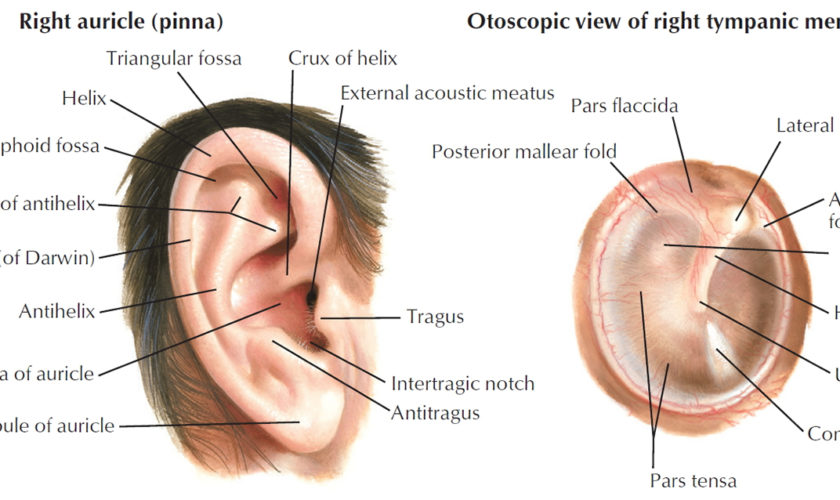

Figure 1. Ear structure

Figure 2. Ear anatomy

Parts of the ear

External (Outer) Ear

The external (outer) ear consists of the auricle, external auditory canal, and eardrum (Figure 1 and 2). The auricle or pinna is a flap of elastic cartilage shaped like the flared end of a trumpet and covered by skin. The rim of the auricle is the helix; the inferior portion is the lobule. Ligaments and muscles attach the auricle to the head. The external auditory canal is a curved tube about 2.5 cm (1 in.) long that lies in the temporal bone and leads to the eardrum.

The tympanic membrane or ear drum is a thin, semitransparent partition between the external auditory canal and middle ear. The tympanic membrane is covered by epidermis and lined by simple cuboidal epithelium. Between the epithelial layers is connective tissue composed of collagen, elastic fibers, and fibroblasts. Tearing of the tympanic membrane is called a perforated eardrum. It may be due to pressure from a cotton swab, trauma, or a middle ear infection, and usually heals within a month. The tympanic membrane may be examined directly by an otoscope, a viewing instrument that illuminates and magnifies the external auditory canal and tympanic membrane.

Near the exterior opening, the external auditory canal contains a few hairs and specialized sweat glands called ceruminous glands that secrete earwax or cerumen. The combination of hairs and cerumen helps prevent dust and foreign objects from entering the ear. Cerumen also prevents damage to the delicate skin of the external ear canal by water and insects. Cerumen usually dries up and falls out of the ear canal. However, some people produce a large amount of cerumen, which can become impacted and can muffle incoming sounds. The treatment for impacted cerumen is usually periodic ear irrigation or removal of wax with a blunt instrument by trained medical personnel.

Middle Ear

The middle ear is a small, air-filled cavity in the petrous portion of the temporal bone that is lined by epithelium. It is separated from the external ear by the tympanic membrane and from the internal ear by a thin bony partition that contains two small openings: the oval window and the round window.

Extending across the middle ear and attached to it by ligaments are the three smallest bones in the body, the auditory ossicles, which are connected by synovial joints. The bones, named for their shapes, are the malleus, incus, and stapes—commonly called the hammer, anvil, and stirrup, respectively. The “handle” of the malleus attaches to the internal surface of the tympanic membrane. The head of the malleus articulates with the body of the incus. The incus, the middle bone in the series, articulates with the head of the stapes. The base or footplate of the stapes fits into the oval window. Directly below the oval window is another opening, the round window, which is enclosed by a membrane called the secondary tympanic membrane. Besides the ligaments, two tiny skeletal muscles also attach to the ossicles (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Middle ear and auditory ossicles

The tensor tympani muscle, which is supplied by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal (V) nerve, limits movement and increases tension on the eardrum to prevent damage to the inner ear from loud noises. The stapedius muscle, which is supplied by the facial (VII) nerve, is the smallest skeletal muscle in the human body. By dampening large vibrations of the stapes due to loud noises, it protects the oval window, but it also decreases the sensitivity of hearing. For this reason, paralysis of the stapedius muscle is associated with hyperacusia, which is abnormally sensitive hearing. Because it takes a fraction of a second for the tensor tympani and stapedius muscles to contract, they can protect the inner ear from prolonged loud noises but not from brief ones such as a gunshot.

The anterior wall of the middle ear contains an opening that leads directly into the auditory tube or pharyngotympanic tube, commonly known as the eustachian tube. The auditory tube, which consists of both bone and elastic cartilage, connects the middle ear with the nasopharynx (superior portion of the throat). It is normally closed at its medial (pharyngeal) end. During swallowing and yawning, it opens, allowing air to enter or leave the middle ear until the pressure in the middle ear equals the atmospheric pressure. Most of us have experienced our ears popping as the pressures equalize. When the pressures are balanced, the tympanic membrane vibrates freely as sound waves strike it. If the pressure is not equalized, intense pain, hearing impairment, ringing in the ears, and vertigo could develop. The auditory tube also is a route for pathogens to travel from the nose and throat to the middle ear, causing the most common type of ear infection.

Internal (Inner)

Ear The internal (inner) ear is also called the labyrinth because of its complicated series of canals (Figure 4, 5 and 6). Structurally, it consists of two main divisions: an outer bony labyrinth that encloses an inner membranous labyrinth. It is like long balloons put inside a rigid tube. The bony labyrinth is a series of cavities in the petrous portion of the temporal bone divided into three areas: (1) the semicircular canals, (2) the vestibule, and (3) the cochlea.

Figure 4. Parts of the inner ear

The bony labyrinth is lined with periosteum and contains perilymph. This fluid, which is chemically similar to cerebrospinal fluid, surrounds the membranous labyrinth, a series of epithelial sacs and tubes inside the bony labyrinth that have the same general form as the bony labyrinth and house the receptors for hearing and equilibrium. The epithelial membranous labyrinth contains endolymph. The level of potassium ions (K+) in endolymph is unusually high for an extracellular fluid, and potassium ions play a role in the generation of auditory signals.

The vestibule is the oval central portion of the bony labyrinth. The membranous labyrinth in the vestibule consists of two sacs called the utricle (little bag) and the saccule (little sac), which are connected by a small duct. Projecting superiorly and posteriorly from the vestibule are the three bony semicircular canals, each of which lies at approximately right angles to the other two. Based on their positions, they are named the anterior, posterior, and lateral semicircular canals. The anterior and posterior semicircular canals are vertically oriented; the lateral one is horizontally oriented. At one end of each canal is a swollen enlargement called the ampulla. The portions of the membranous labyrinth that lie inside the bony semicircular canals are called the semicircular ducts. These structures connect with the utricle of the vestibule.

The vestibular branch of the vestibulocochlear (cranial nerve VIII) nerve consists of ampullary, utricular, and saccular nerves. These nerves contain both first-order sensory neurons and efferent neurons that synapse with receptors for equilibrium. The first-order sensory neurons carry sensory information from the receptors, and the efferent neurons carry feedback signals to the receptors, apparently to modify their sensitivity. Cell bodies of the sensory neurons are located in the vestibular ganglia.

Figure 5. Inner ear bones

Note: A closer look at the inner ear. Perilymph separates the bony (osseous) labyrinth of the inner ear from the membranous labyrinth, which contains endolymph. Note that areas of bony labyrinth have been removed to reveal underlying structures.

Figure 6. The Cochlea (cross section view)

Note: a) Cross section of the cochlea. (b) The spiral organ and the tectorial membrane.

Anterior to the vestibule is the cochlea, a bony spiral canal that resembles a snail’s shell and makes almost three turns around a central bony core called the modiolus. Sections through the cochlea reveal that it is divided into three channels: cochlear duct, scala vestibuli, and scala tympani. The cochlear duct or scala media is a continuation of the membranous labyrinth into the cochlea; it is filled with endolymph. The channel above the cochlear duct is the scala vestibuli, which ends at the oval window. The channel below is the scala tympani, which ends at the round window. Both the scala vestibuli and scala tympani are part of the bony labyrinth of the cochlea; therefore, these chambers are filled with perilymph. The scala vestibuli and scala tympani are completely separated by the cochlear duct, except for an opening at the apex of the cochlea, the helicotrema.

The cochlea adjoins the wall of the vestibule, into which the scala vestibuli opens. The perilymph in the vestibule is continuous with that of the scala vestibuli. The vestibular membrane separates the cochlear duct from the scala vestibuli, and the basilar membrane separates the cochlear duct from the scala tympani. Resting on the basilar membrane is the spiral organ or organ of Corti. The spiral organ is a coiled sheet of epithelial cells, including supporting cells and about 16,000 hair cells, which are the receptors for hearing.

There are two groups of hair cells: The inner hair cells are arranged in a single row, whereas the outer hair cells are arranged in three rows. At the apical tip of each hair cell are stereocilia that extend into the endolymph of the cochlear duct. Despite their name, stereocilia are actually long, hairlike microvilli arranged in several rows of graded height.

At their basal ends, inner and outer hair cells synapse both with first-order sensory neurons and with motor neurons from the cochlear branch of the vestibulocochlear (VIII) nerve. Cell bodies of the sensory neurons are located in the spiral ganglion. Although outer hair cells outnumber them by 3 to 1, the inner hair cells synapse with 90–95% of the first-order sensory neurons in the cochlear nerve that relay auditory information to the brain. By contrast, 90% of the motor neurons in the cochlear nerve synapse with outer hair cells. The tectorial membrane, a flexible gelatinous membrane, covers the hair cells of the spiral organ. In fact, the ends of the stereocilia of the hair cells are embedded in the tectorial membrane while the bodies of the hair cells rest on the basilar membrane. Inner and outer hair cells have diff erent functional roles. Inner hair cells are the receptors for hearing: They convert the mechanical vibrations of sound into electrical signals. Outer hair cells do not serve as hearing receptors; instead, they increase the sensitivity of the inner hair cells.

Mechanism for Hearing

First, sound vibrations travel from the eardrum through the ossicles, causing the stapes to oscillate back and forth against the oval window. This oscillation sets up pressure waves in the perilymph of the scala vestibuli, which are transferred to the endolymph of the cochlear duct. These waves cause the basilar membrane to vibrate up and down. The hair cells in the spiral organ move along with the basilar membrane, but the overlying tectorial membrane (in which the hairs are anchored) does not move. Therefore, the movements of the hair cells cause their hairs to bend. Each time such bending occurs in a specific direction, the hair cells release neurotransmitters that excite the cochlear nerve fibers, which carry the vibratory (sound) information to the brain. The vibrations of the basilar membrane set the perilymph vibrating in the underlying scala tympani. These vibrations then travel to the round window, where they push on the membrane that covers that window, thereby dissipating their remaining energy into the air of the middle ear cavity. Without this release mechanism, echoes would reverberate within the rigid cochlear box, disrupting sound reception.

The inner and outer hair cells in the spiral organ have different functions. The inner hair cells are the true receptors that transmit the vibrations of the basilar membrane to the cochlear nerve. The outer hair cells are involved with actively tuning the cochlea and amplifying the signal. The outer hair cells receive efferent fibers from the brain that cause these cells to stretch and contract, enhancing the responsiveness of the inner hair cell receptors. Overall, this active mechanism amplifies sounds some 100 times, so that we can hear the faintest sounds.The mobility of the outer hair cells is also responsible for producing ear sounds (otoacoustic emissions). Detection of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions is used to test hearing in newborns.

Ear problems

Swimmer’s ear

Swimmer’s ear is an infection in the outer ear canal, which runs from your eardrum to the outside of your head 1. It’s often brought on by water that remains in your ear after swimming, creating a moist environment that aids bacterial growth.

Putting fingers, cotton swabs or other objects in your ears also can lead to swimmer’s ear by damaging the thin layer of skin lining your ear canal 1.

Swimmer’s ear is also known as otitis externa. The most common cause of this infection is bacteria invading the skin inside your ear canal. Usually you can treat swimmer’s ear with eardrops. Prompt treatment can help prevent complications and more-serious infections.

Causes of Swimmer’s ear

Swimmer’s ear is an infection that’s usually caused by bacteria commonly found in water and soil. Infections caused by a fungus or a virus are less common. Swimmer’s ear is more common among children in their teens and young adults. It may occur with a middle ear infection or a respiratory infection such as a cold.

Swimming in unclean water can lead to swimmer’s ear. Bacteria commonly often found in water can cause ear infections. Rarely, the infection may be caused by a fungus.

Other causes of swimmer’s ear include:

- Scratching the ear or inside the ear

- Getting something stuck in the ear

Trying to clean (wax from the ear canal) with cotton swabs or small objects can damage the skin.

Long-term (chronic) swimmer’s ear may be due to:

- Allergic reaction to something placed in the ear

- Chronic skin conditions, such as eczema or psoriasis

Your ear’s natural defenses

Your outer ear canals have natural defenses that help keep them clean and prevent infection. Protective features include:

- Glands that secrete a waxy substance (cerumen). These secretions form a thin, water-repellent film on the skin inside your ear. Cerumen is also slightly acidic, which helps further discourage bacterial growth. In addition, cerumen collects dirt, dead skin cells and other debris and helps move these particles out of your ear. The waxy clump that results is the familiar earwax you find at the opening of your ear canal.

- Downward slope of your ear canal. Your ear canal slopes down slightly from your middle ear to your outer ear, helping water drain out.

How the swimmer’s ear occurs

If you have swimmer’s ear, your natural defenses have been overwhelmed. Conditions that can weaken your ear’s defenses and promote bacterial growth include:

- Excess moisture in your ear. Heavy perspiration, prolonged humid weather or water that remains in your ear after swimming can create a favorable environment for bacteria.

- Scratches or abrasions in your ear canal. Cleaning your ear with a cotton swab or hairpin, scratching inside your ear with a finger, or wearing headphones or hearing aids can cause small breaks in the skin that allow bacteria to grow.

- Sensitivity reactions. Hair products or jewelry can cause allergies and skin conditions that promote infection.

Risk factors for swimmer’s ear

Factors that may increase your risk of swimmer’s ear include:

- Swimming

- Swimming in water with elevated bacteria levels, such as a lake rather than a well-maintained pool

- A narrow ear canal — for example, in a child — that can more easily trap water

- Aggressive cleaning of the ear canal with cotton swabs or other objects

- Use of certain devices, such as headphones or a hearing aid

- Skin allergies or irritation from jewelry, hair spray or hair dyes

Symptoms of Swimmer’s ear

Swimmer’s ear symptoms are usually mild at first, but they may get worse if your infection isn’t treated or spreads. Doctors often classify swimmer’s ear according to mild, moderate and advanced stages of progression.

Mild signs and symptoms

- Itching in your ear canal

- Slight redness inside your ear

- Mild discomfort that’s made worse by pulling on your outer ear (pinna, or auricle) or pushing on the little “bump” (tragus) in front of your ear

- Some drainage of clear, odorless fluid

Moderate progression

- More intense itching

- Increasing pain

- More extensive redness in your ear

- Excessive fluid drainage

- Discharge of pus

- Feeling of fullness inside your ear and partial blockage of your ear canal by swelling, fluid and debris

- Decreased or muffled hearing

Advanced progression

- Severe pain that may radiate to your face, neck or side of your head

- Complete blockage of your ear canal

- Redness or swelling of your outer ear

- Swelling in the lymph nodes in your neck

- Fever

When to see a doctor

See your doctor if you’re experiencing any signs or symptoms of swimmer’s ear, even if they’re mild.

Call your doctor immediately or visit the emergency room if you have:

- Severe pain

- Fever

Complications of Swimmer’s ear

Swimmer’s ear usually isn’t serious if treated promptly, but complications can occur.

- Temporary hearing loss. You may experience muffled hearing that usually gets better after the infection clears up.

- Long-term infection (chronic otitis externa). An outer ear infection is usually considered chronic if signs and symptoms persist for more than three months.

- Chronic infections are more common if there are conditions that make treatment difficult, such as a rare strain of bacteria, an allergic skin reaction, an allergic reaction to antibiotic eardrops, or a combination of a bacterial and fungal infection.

- Deep tissue infection (cellulitis). Rarely, swimmer’s ear may result in the spread of infection into deep layers and connective tissues of the skin.

- Bone and cartilage damage (necrotizing otitis externa). An outer ear infection that spreads can cause inflammation and damage to the skin and cartilage of the outer ear and bones of the lower part of the skull, causing increasingly severe pain. Older adults, people with diabetes or people with weakened immune systems are at increased risk of this complication. Necrotizing otitis externa is also known as malignant otitis externa, but it’s not a cancer.

- More widespread infection. If swimmer’s ear develops into necrotizing otitis externa, the infection may spread and affect other parts of your body, such as the brain or nearby nerves. This rare complication can be life-threatening.

Prevention of Swimmer’s ear

Follow these tips to avoid swimmer’s ear:

- Keep your ears dry. Dry your ears thoroughly after exposure to moisture from swimming or bathing. Dry only your outer ear, wiping it slowly and gently with a soft towel or cloth. Tip your head to the side to help water drain from your ear canal. You can dry your ears with a blow dryer if you put it on the lowest setting and hold it at least a foot (about 0.3 meters) away from the ear.

- At-home preventive treatment. If you know you don’t have a punctured eardrum, you can use homemade preventive eardrops before and after swimming. A mixture of 1 part white vinegar to 1 part rubbing alcohol may help promote drying and prevent the growth of bacteria and fungi that can cause swimmer’s ear. Pour 1 teaspoon (about 5 milliliters) of the solution into each ear and let it drain back out. Similar over-the-counter solutions may be available at your drugstore.

- Swim wisely. Watch for signs alerting swimmers to high bacterial counts and don’t swim on those days.

- DO NOT scratch the ears or insert cotton swabs or other objects in the ears.

- Avoid putting foreign objects in your ear. Never attempt to scratch an itch or dig out earwax with items such as a cotton swab, paper clip or hairpin. Using these items can pack material deeper into your ear canal, irritate the thin skin inside your ear or break the skin.

- Protect your ears from irritants. Put cotton balls in your ears while applying products such as hair sprays and hair dyes.

- Use caution after an ear infection or surgery. If you’ve recently had an ear infection or ear surgery, talk to your doctor before you go swimming.

Diagnosis of swimmer’s ear

Doctors can usually diagnose swimmer’s ear during an office visit. If your infection is at an advanced stage or persists, you may need further evaluation.

Initial testing

Your doctor will likely diagnose swimmer’s ear based on symptoms you report, questions he or she asks, and an office examination. You probably won’t need a lab test at your first visit. Your doctor’s initial evaluation will usually include:

- Examination of your ear canal with a lighted instrument (otoscope). Your ear canal may appear red, swollen and scaly. Flakes of skin and other debris may be present in the ear canal.

- Visualization of your eardrum (tympanic membrane) to be sure it isn’t torn or damaged. If the view of your eardrum is blocked, your doctor will clear your ear canal with a small suction device or an instrument with a tiny loop or scoop on the end (ear curette).

Further testing

Depending on the initial assessment, symptom severity or the stage of your swimmer’s ear, your doctor may recommend additional evaluation.

- If your eardrum is damaged or torn, your doctor will likely refer you to an ear, nose and throat specialist (ENT). The specialist will examine the condition of your middle ear to determine if that’s the primary site of infection. This examination is important because some treatments intended for an infection in the outer ear canal aren’t appropriate for treating the middle ear.

- If your infection doesn’t respond to treatment, your doctor may take a sample of discharge or debris from your ear at a later appointment and send it to a lab to identify the exact microorganism causing your infection.

Treatment for swimmer’s ear

The goal of treatment is to stop the infection and allow your ear canal to heal.

Cleaning

Cleaning your outer ear canal is necessary to help eardrops flow to all infected areas. Your doctor will use a suction device or ear curette to clean away any discharge, clumps of earwax, flaky skin and other debris.

Medications for infection

For most cases of swimmer’s ear, your doctor will prescribe eardrops that have some combination of the following ingredients, depending on the type and seriousness of your infection:

- Acidic solution to help restore your ear’s normal antibacterial environment

- Steroid to reduce inflammation

- Antibiotic to fight bacteria

- Antifungal medication to fight an infection caused by a fungus

Ask your doctor about the best method for taking your eardrops. Some ideas that may help you use eardrops include the following:

- Reduce the discomfort of cool drops by holding the bottle in your hand for a few minutes to bring the temperature of the drops closer to body temperature.

- Lie on your side with your infected ear up for a few minutes to help medication travel through the full length of your ear canal.

- If possible, have someone help you put the drops in your ear.

If your ear canal is completely blocked by swelling, inflammation or excess discharge, your doctor may insert a wick made of cotton or gauze to promote drainage and help draw medication into your ear canal.

If your infection is more advanced or doesn’t respond to treatment with eardrops, your doctor may prescribe oral antibiotics.

Medications for pain

Your doctor may recommend easing the discomfort of swimmer’s ear with over-the-counter pain relievers, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve, others) or acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).

If your pain is severe or your swimmer’s ear is at a more advanced stage, your doctor may prescribe a stronger medication for pain relief.

Helping your treatment work

During treatment, the following steps will help keep your ears dry and avoid further irritation:

- Don’t swim or scuba dive.

- Avoid flying.

- Don’t wear an earplug, hearing aid or headphones before pain or discharge has stopped.

- Avoid getting water in your ear canal when bathing. Use a cotton ball coated with petroleum jelly to protect your ear during a bath.

Ruptured eardrum (perforated eardrum)

A ruptured eardrum — or tympanic membrane perforation as it’s medically known — is a hole or tear in the thin tissue that separates your ear canal from your middle ear (eardrum) 2.

A ruptured eardrum can result in hearing loss. A ruptured eardrum can also make your middle ear vulnerable to infections or injury.

A ruptured eardrum usually heals within a few weeks without treatment. Sometimes, however, a ruptured eardrum requires a procedure or surgical repair to heal.

If you think that you have a ruptured eardrum, be careful to keep your ears dry to prevent infection. Don’t go swimming. To keep water out of your ear when showering or bathing, use a moldable, waterproof silicone earplug or put a cotton ball coated with petroleum jelly in your outer ear.

Don’t put medication drops in your ear unless your doctor prescribes them specifically for infection related to your perforated eardrum.

Causes of a ruptured or perforated eardrum

Causes of a ruptured, or perforated, eardrum may include:

- Middle ear infection (otitis media). A middle ear infection often results in the accumulation of fluids in your middle ear. Pressure from these fluids can cause the eardrum to rupture.

- Barotrauma. Barotrauma is stress exerted on your eardrum when the air pressure in your middle ear and the air pressure in the environment are out of balance. If the pressure is severe, your eardrum can rupture. Barotrauma is most often caused by air pressure changes associated with air travel.

- Other events that can cause sudden changes in pressure — and possibly a ruptured eardrum — include scuba diving and a direct blow to the ear, such as the impact of an automobile air bag.

- Loud sounds or blasts (acoustic trauma). A loud sound or blast, as from an explosion or gunshot — essentially an overpowering sound wave — can cause a tear in your eardrum.

- Foreign objects in your ear. Small objects, such as a cotton swab or hairpin, can puncture or tear the eardrum.

- Severe head trauma. Severe injury, such as skull fracture, may cause the dislocation or damage to middle and inner ear structures, including your eardrum.

Complications of of a ruptured or perforated eardrum

Your eardrum (tympanic membrane) has two primary roles:

- Hearing. When sound waves strike it, your eardrum vibrates — the first step by which structures of your middle and inner ears translate sound waves into nerve impulses.

- Protection. Your eardrum also acts as a barrier, protecting your middle ear from water, bacteria and other foreign substances.

If your eardrum ruptures, complications can occur while your eardrum is healing or if it fails to heal. Possible complications include:

- Hearing loss. Usually, hearing loss is temporary, lasting only until the tear or hole in your eardrum has healed. The size and location of the tear can affect the degree of hearing loss.

- Middle ear infection (otitis media). A perforated eardrum can allow bacteria to enter your ear. If a perforated eardrum doesn’t heal or isn’t repaired, you may be vulnerable to ongoing (chronic) infections that can cause permanent hearing loss.

- Middle ear cyst (cholesteatoma). A cholesteatoma is a cyst in your middle ear composed of skin cells and other debris. Ear canal debris normally travels to your outer ear with the help of ear-protecting earwax. If your eardrum is ruptured, the skin debris can pass into your middle ear and form a cyst. A cholesteatoma provides a friendly environment for bacteria and contains proteins that can damage bones of your middle ear.

Prevention of a ruptured or perforated eardrum

Follow these tips to avoid a ruptured or perforated eardrum:

- Get treatment for middle ear infections. Be aware of the signs and symptoms of middle ear infection, including earache, fever, nasal congestion and reduced hearing. Children with a middle ear infection often rub or pull on their ears. Seek prompt evaluation from your primary care doctor to prevent potential damage to the eardrum.

- Protect your ears during flight. If possible, don’t fly if you have a cold or an active allergy that causes nasal or ear congestion. During takeoffs and landings, keep your ears clear with pressure-equalizing earplugs, yawning or chewing gum. Or use the Valsalva maneuver — gently blowing, as if blowing your nose, while pinching your nostrils and keeping your mouth closed. Don’t sleep during ascents and descents.

- Keep your ears free of foreign objects. Never attempt to dig out excess or hardened earwax with items such as a cotton swab, paper clip or hairpin. These items can easily tear or puncture your eardrum. Teach your children about the damage that can be done by putting foreign objects in their ears.

- Guard against excessive noise. Protect your ears from unnecessary damage by wearing protective earplugs or earmuffs in your workplace or during recreational activities if loud noise is present.

Symptoms of a ruptured or perforated eardrum

Signs and symptoms of a ruptured eardrum may include:

- Ear pain that may subside quickly

- Clear, pus-filled or bloody drainage from your ear

- Hearing loss

- Ringing in your ear (tinnitus)

- Spinning sensation (vertigo)

- Nausea or vomiting that can result from vertigo

When to see a doctor

Call your doctor if you experience any of the signs or symptoms of a ruptured eardrum or pain or discomfort in your ears. Your middle and inner ears are composed of delicate mechanisms that are sensitive to injury or disease. Prompt and appropriate treatment is important to preserve your hearing.

Diagnosis of a ruptured or perforated eardrum

Your family doctor or ENT specialist can often determine if you have a perforated eardrum with a visual inspection using a lighted instrument (otoscope).

He or she may conduct or order additional tests to determine the cause of the rupture or degree of damage. These tests include:

- Laboratory tests. If there’s discharge from your ear, your doctor may order a laboratory test or culture to detect a bacterial infection of your middle ear.

- Tuning fork evaluation. Tuning forks are two-pronged, metal instruments that produce sounds when struck. Simple tests with tuning forks can help your doctor detect hearing loss. A tuning fork evaluation may also reveal whether hearing loss is caused by damage to the vibrating parts of your middle ear (including your eardrum), damage to sensors or nerves of your inner ear, or damage to both.

- Tympanometry. A tympanometer uses a device inserted into your ear canal that measures the response of your eardrum to slight changes in air pressure. Certain patterns of response can indicate a perforated eardrum.

- Audiology exam. If other hearing tests are inconclusive, your doctor may order a series of strictly calibrated tests conducted in a soundproof booth that measure how well you hear sounds at different volumes and pitches (audiology exam).

Treatment of a ruptured or perforated eardrum

Most perforated eardrums heal without treatment within a few weeks. Your doctor may prescribe antibiotic drops if there’s evidence of infection. If the tear or hole in your eardrum doesn’t heal by itself, treatment will involve procedures to close the perforation. These may include:

- Eardrum patch. If the tear or hole in your eardrum doesn’t close on its own, an ENT specialist may seal it with a patch. With this office procedure, your ENT doctor may apply a chemical to the edges of the tear to stimulate growth and then apply a patch over the hole. The procedure may need to be repeated more than once before the hole closes.

- Surgery. If a patch doesn’t result in proper healing or your ENT doctor determines that the tear isn’t likely to heal with a patch, he or she may recommend surgery. The most common surgical procedure is called tympanoplasty. Your surgeon grafts a tiny patch of your own tissue to close the hole in the eardrum. This procedure is done on an outpatient basis, meaning you can usually go home the same day unless medical anesthesia conditions require a longer hospital stay.

Home remedies for a ruptured or perforated eardrum

A ruptured eardrum usually heals on its own within weeks. In some cases, healing takes months. Until your doctor tells you that your ear is healed, protect it by doing the following:

- Keep your ear dry. Place a waterproof silicone earplug or cotton ball coated with petroleum jelly in your ear when showering or bathing.

- Refrain from cleaning your ears. Give your eardrum time to heal completely.

- Avoid blowing your nose. The pressure created when blowing your nose can damage your healing eardrum.

Middle Ear Infection

An middle ear infection (acute otitis media) is most often a bacterial or viral infection that affects the middle ear, the air-filled space behind the eardrum that contains the tiny vibrating bones of the ear 3. Children are more likely than adults to get ear infections.

Ear infections frequently are painful because of inflammation and buildup of fluids in the middle ear.

Because ear infections often clear up on their own, treatment may begin with managing pain and monitoring the problem. Ear infection in infants and severe cases in general often require antibiotic medications. Long-term problems related to ear infections — persistent fluids in the middle ear, persistent infections or frequent infections — can cause hearing problems and other serious complications.

Symptoms of middle ear infection

The onset of signs and symptoms of ear infection is usually rapid.

Children

Signs and symptoms common in children include:

- Ear pain, especially when lying down

- Tugging or pulling at an ear

- Difficulty sleeping

- Crying more than usual

- Acting more irritable than usual

- Difficulty hearing or responding to sounds

- Loss of balance

- Fever of 100 F (38 C) or higher

- Drainage of fluid from the ear

- Headache

- Loss of appetite

Adults

Common signs and symptoms in adults include:

- Ear pain

- Drainage of fluid from the ear

- Diminished hearing

When to see a doctor

Signs and symptoms of an ear infection can indicate a number of conditions. It’s important to get an accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment. Call your child’s doctor if:

- Symptoms last for more than a day

- Symptoms are present in a child less than 6 months of age

- Ear pain is severe

- Your infant or toddler is sleepless or irritable after a cold or other upper respiratory infection

- You observe a discharge of fluid, pus or bloody discharge from the ear

An adult with ear pain or discharge should see a doctor as soon as possible.

Causes of middle ear infection

An ear infection is caused by a bacterium or virus in the middle ear. This infection often results from another illness — cold, flu or allergy — that causes congestion and swelling of the nasal passages, throat and eustachian tubes.

Role of eustachian tubes

The eustachian tubes are a pair of narrow tubes that run from each middle ear to high in the back of the throat, behind the nasal passages. The throat end of the tubes open and close to:

- Regulate air pressure in the middle ear

- Refresh air in the ear

- Drain normal secretions from the middle ear

Swelling, inflammation and mucus in the eustachian tubes from an upper respiratory infection or allergy can block them, causing the accumulation of fluids in the middle ear. A bacterial or viral infection of this fluid is usually what produces the symptoms of an ear infection.

Ear infections are more common in children, in part, because their eustachian tubes are narrower and more horizontal — factors that make them more difficult to drain and more likely to get clogged.

Role of adenoids

Adenoids are two small pads of tissues high in the back of the nose believed to play a role in immune system activity. This function may make them particularly vulnerable to infection, inflammation and swelling.

Because adenoids are near the opening of the eustachian tubes, inflammation or enlargement of the adenoids may block the tubes, thereby contributing to middle ear infection. Inflammation of adenoids is more likely to play a role in ear infections in children because children have relatively larger adenoids.

Related conditions

Conditions of the middle ear that may be related to an ear infection or result in similar middle ear problems include the following:

- Otitis media with effusion is inflammation and fluid buildup (effusion) in the middle ear without bacterial or viral infection. This may occur because the fluid buildup persists after an ear infection has resolved. It may also occur because of some dysfunction or noninfectious blockage of the eustachian tubes.

- Chronic otitis media with effusion occurs when fluid remains in the middle ear and continues to return without bacterial or viral infection. This makes children susceptible to new ear infections, and may affect hearing.

- Chronic suppurative otitis media is a persistent ear infection that often results in tearing or perforation of the eardrum.

Risk factors for middle ear infection

Risk factors for ear infections include:

- Age. Children between the ages of 6 months and 2 years are more susceptible to ear infections because of the size and shape of their eustachian tubes and because of their poorly developed immune systems.

- Group child care. Children cared for in group settings are more likely to get colds and ear infections than are children who stay home because they’re exposed to more infections, such as the common cold.

- Infant feeding. Babies who drink from a bottle, especially while lying down, tend to have more ear infections than do babies who are breast-fed.

- Seasonal factors. Ear infections are most common during the fall and winter when colds and flu are prevalent. People with seasonal allergies may have a greater risk of ear infections during seasonal high pollen counts.

- Poor air quality. Exposure to tobacco smoke or high levels of air pollution can increase the risk of ear infection.

Complications of middle ear infection

Most ear infections don’t cause long-term complications. Frequent or persistent infections and persistent fluid buildup can result in some serious complications:

- Impaired hearing. Mild hearing loss that comes and goes is fairly common with an ear infection, but it usually returns to what it was before the infection after the infection clears. Persistent infection or persistent fluids in the middle ear may result in more significant hearing loss. If there is some permanent damage to the eardrum or other middle ear structures, permanent hearing loss may occur.

- Speech or developmental delays. If hearing is temporarily or permanently impaired in infants and toddlers, they may experience delays in speech, social and developmental skills.

- Spread of infection. Untreated infections or infections that don’t respond well to treatment can spread to nearby tissues. Infection of the mastoid, the bony protrusion behind the ear, is called mastoiditis. This infection can result in damage to the bone and the formation of pus-filled cysts. Rarely, serious middle ear infections spread to other tissues in the skull, including the brain or the membranes surrounding the brain (meningitis).

- Tearing of the eardrum. Most eardrum tears heal within 72 hours. In some cases, surgical repair is needed.

Prevention of middle ear infection

The following tips may reduce the risk of developing ear infections:

- Prevent common colds and other illnesses. Teach your children to wash their hands frequently and thoroughly and to not share eating and drinking utensils. Teach your children to cough or sneeze into their arm crook. If possible, limit the time your child spends in group child care. A child care setting with fewer children may help. Try to keep your child home from child care or school when ill.

- Avoid secondhand smoke. Make sure that no one smokes in your home. Away from home, stay in smoke-free environments.

- Breast-feed your baby. If possible, breast-feed your baby for at least six months. Breast milk contains antibodies that may offer protection from ear infections.

- If you bottle-feed, hold your baby in an upright position. Avoid propping a bottle in your baby’s mouth while he or she is lying down. Don’t put bottles in the crib with your baby.

- Talk to your doctor about vaccinations. Ask your doctor about what vaccinations are appropriate for your child. Seasonal flu shots, pneumococcal and other bacterial vaccines may help prevent ear infections.

Diagnosis of middle ear infection

Your doctor can usually diagnose an ear infection or another condition based on the symptoms you describe and an exam. The doctor will likely use a lighted instrument (an otoscope) to look at the ears, throat and nasal passage. He or she will also likely listen to your child breathe with a stethoscope.

Pneumatic otoscope

An instrument called a pneumatic otoscope is often the only specialized tool a doctor needs to make a diagnosis of an ear infection. This instrument enables the doctor to look in the ear and judge whether there is fluid behind the eardrum. With the pneumatic otoscope, the doctor gently puffs air against the eardrum. Normally, this puff of air would cause the eardrum to move. If the middle ear is filled with fluid, your doctor will observe little to no movement of the eardrum.

Additional tests

Your doctor may perform other diagnostic tests if there is any doubt about a diagnosis, if the condition hasn’t responded to previous treatments, or if there are other persistent or serious problems.

- Tympanometry. This test measures the movement of the eardrum. The device, which seals off the ear canal, adjusts air pressure in the canal, thereby causing the eardrum to move. The device quantifies how well the eardrum moves and provides an indirect measure of pressure within the middle ear.

- Acoustic reflectometry. This test measures how much sound emitted from a device is reflected back from the eardrum — an indirect measure of fluids in the middle ear. Normally, the eardrum absorbs most of the sound. However, the more pressure there is from fluid in the middle ear, the more sound the eardrum will reflect.

- Tympanocentesis. Rarely, a doctor may use a tiny tube that pierces the eardrum to drain fluid from the middle ear — a procedure called tympanocentesis. Tests to determine the infectious agent in the fluid may be beneficial if an infection hasn’t responded well to previous treatments.

Other tests. If your child has had persistent ear infections or persistent fluid buildup in the middle ear, your doctor may refer you to a hearing specialist (audiologist), speech therapist or developmental therapist for tests of hearing, speech skills, language comprehension or developmental abilities.

What a diagnosis means

- Acute otitis media. The diagnosis of “ear infection” is generally shorthand for acute otitis media. Your doctor likely makes this diagnosis if he or she observes signs of fluid in the middle ear, if there are signs or symptoms of an infection, and if the onset of symptoms was relatively sudden.

- Otitis media with effusion. If the diagnosis is otitis media with effusion, the doctor has found evidence of fluid in the middle ear, but there are presently no signs or symptoms of infection.

- Chronic suppurative otitis media. If the doctor makes a diagnosis of chronic suppurative otitis media, he or she has found that a persistent ear infection resulted in tearing or perforation of the eardrum.

Treatment for middle ear infection

Some ear infections resolve without treatment with antibiotics. What’s best for your child depends on many factors, including your child’s age and the severity of symptoms.

A wait-and-see approach

Symptoms of ear infections usually improve within the first couple of days, and most infections clear up on their own within one to two weeks without any treatment. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians recommend a wait-and-see approach as one option for:

- Children 6 to 23 months with mild inner ear pain in one ear for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 F (39 C)

- Children 24 months and older with mild inner ear pain in one or both ears for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 F (39 C)

Some evidence suggests that treatment with antibiotics might be beneficial for certain children with ear infections. Talk to your doctor about the benefits of antibiotics weighed against the potential side effects and concern about overuse of antibiotics creating strains of resistant disease.

Managing pain

Your doctor will advise you on treatments to lessen pain from an ear infection. These may include the following:

- A warm compress. Placing a warm, moist washcloth over the affected ear may lessen pain.

- Pain medication. Your doctor may advise the use of over-the-counter acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) to relieve pain. Use the drugs as directed on the label. Use caution when giving aspirin to children or teenagers. Children and teenagers recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms should never take aspirin because aspirin has been linked with Reye’s syndrome. Talk to your doctor if you have concerns.

Antibiotic therapy

After an initial observation period, your doctor may recommend antibiotic treatment for an ear infection in the following situations:

- Children 6 months and older with moderate to severe ear pain in one or both ears for at least 48 hours or a temperature of 102.2 F (39 C) or higher

- Children 6 to 23 months with mild inner ear pain in one or both ears for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 F (39 C)

- Children 24 months and older with mild inner ear pain in one or both ears for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 F (39 C)

Children younger than 6 months of age with confirmed acute otitis media are more likely to be treated with antibiotics without the initial observational waiting time.

Even after symptoms have improved, be sure to use all of the antibiotic as directed. Failing to do so can result in recurring infection and resistance of bacteria to antibiotic medications. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about what to do if you accidentally skip a dose.

Ear tubes

If your child has recurrent otitis media or otitis media with effusion, your doctor may recommend a procedure to drain fluid from the middle ear. Otitis media is defined as three episodes of infection in six months or four episodes of infection in a year with at least one occurring in the past six months. Otitis media with effusion is persistent fluid buildup in the ear after an infection has cleared up or in the absence of any infection.

During an outpatient surgical procedure called a myringotomy, a surgeon creates a tiny hole in the eardrum that enables him or her to suction fluids out of the middle ear. A tiny tube (tympanostomy tube) is placed in the opening to help ventilate the middle ear and prevent the accumulation of more fluids. Some tubes are intended to stay in place for six months to a year and then fall out on their own. Other tubes are designed to stay in longer and may need to be surgically removed.

The eardrum usually closes up again after the tube falls out or is removed.

Treatment for chronic suppurative otitis media

Chronic infection that results in perforation of the eardrum — chronic suppurative otitis media — is difficult to treat. It’s often treated with antibiotics administered as drops. You’ll receive instructions on how to suction fluids out through the ear canal before administering drops.

Monitoring

Children with frequent or persistent infections or with persistent fluid in the middle ear will need to be monitored closely. Talk to your doctor about how often you should schedule follow-up appointments. Your doctor may recommend regular hearing and language tests.

What is Tinnitus

Tinnitus is the perception of noise or ringing in the ears 4. A common problem, tinnitus affects about 1 in 5 people. Tinnitus isn’t a condition itself — it’s a symptom of an underlying condition, such as age-related hearing loss, ear injury or a circulatory system disorder.

Although bothersome, tinnitus usually isn’t a sign of something serious. Although it can worsen with age, for many people, tinnitus can improve with treatment. Treating an identified underlying cause sometimes helps. Other treatments reduce or mask the noise, making tinnitus less noticeable.

Symptoms of Tinnitus

Tinnitus involves the annoying sensation of hearing sound when no external sound is present. Tinnitus symptoms include these types of phantom noises in your ears:

- Ringing

- Buzzing

- Roaring

- Clicking

- Hissing

The phantom noise may vary in pitch from a low roar to a high squeal, and you may hear it in one or both ears. In some cases, the sound can be so loud it can interfere with your ability to concentrate or hear actual sound. Tinnitus may be present all the time, or it may come and go.

There are two kinds of tinnitus.

- Subjective tinnitus is tinnitus only you can hear. This is the most common type of tinnitus. It can be caused by ear problems in your outer, middle or inner ear. It also can be caused by problems with the hearing (auditory) nerves or the part of your brain that interprets nerve signals as sound (auditory pathways).

- Objective tinnitus is tinnitus your doctor can hear when he or she does an examination. This rare type of tinnitus may be caused by a blood vessel problem, a middle ear bone condition or muscle contractions.

When to see a doctor

If you have tinnitus that bothers you, see your doctor.

Make an appointment to see your doctor if:

- You develop tinnitus after an upper respiratory infection, such as a cold, and your tinnitus doesn’t improve within a week.

See your doctor as soon as possible if:

- You have tinnitus that occurs suddenly or without an apparent cause.

- You have hearing loss or dizziness with the tinnitus.

Causes of Tinnitus

A number of health conditions can cause or worsen tinnitus. In many cases, an exact cause is never found.

A common cause of tinnitus is inner ear cell damage. Tiny, delicate hairs in your inner ear move in relation to the pressure of sound waves. This triggers ear cells to release an electrical signal through a nerve from your ear (auditory nerve) to your brain. Your brain interprets these signals as sound. If the hairs inside your inner ear are bent or broken, they can “leak” random electrical impulses to your brain, causing tinnitus.

Other causes of tinnitus include other ear problems, chronic health conditions, and injuries or conditions that affect the nerves in your ear or the hearing center in your brain.

Common causes of tinnitus

In many people, tinnitus is caused by one of these conditions:

- Age-related hearing loss. For many people, hearing worsens with age, usually starting around age 60. Hearing loss can cause tinnitus. The medical term for this type of hearing loss is presbycusis.

- Exposure to loud noise. Loud noises, such as those from heavy equipment, chain saws and firearms, are common sources of noise-related hearing loss.

- Portable music devices, such as MP3 players or iPods, also can cause noise-related hearing loss if played loudly for long periods. Tinnitus caused by short-term exposure, such as attending a loud concert, usually goes away; long-term exposure to loud sound can cause permanent damage.

- Earwax blockage. Earwax protects your ear canal by trapping dirt and slowing the growth of bacteria. When too much earwax accumulates, it becomes too hard to wash away naturally, causing hearing loss or irritation of the eardrum, which can lead to tinnitus.

- Ear bone changes. Stiffening of the bones in your middle ear (otosclerosis) may affect your hearing and cause tinnitus. This condition, caused by abnormal bone growth, tends to run in families.

Other causes of tinnitus

Some causes of tinnitus are less common, including:

- Meniere’s disease. Tinnitus can be an early indicator of Meniere’s disease, an inner ear disorder that may be caused by abnormal inner ear fluid pressure.

- TMJ disorders. Problems with the temporomandibular joint, the joint on each side of your head in front of your ears, where your lower jawbone meets your skull, can cause tinnitus.

- Head injuries or neck injuries. Head or neck trauma can affect the inner ear, hearing nerves or brain function linked to hearing. Such injuries generally cause tinnitus in only one ear.

- Acoustic neuroma. This noncancerous (benign) tumor develops on the cranial nerve that runs from your brain to your inner ear and controls balance and hearing. Also called vestibular schwannoma, this condition generally causes tinnitus in only one ear.

Blood vessel disorders linked to tinnitus

In rare cases, tinnitus is caused by a blood vessel disorder. This type of tinnitus is called pulsatile tinnitus. Causes include:

- Atherosclerosis. With age and buildup of cholesterol and other deposits, major blood vessels close to your middle and inner ear lose some of their elasticity — the ability to flex or expand slightly with each heartbeat. That causes blood flow to become more forceful, making it easier for your ear to detect the beats. You can generally hear this type of tinnitus in both ears.

- Head and neck tumors. A tumor that presses on blood vessels in your head or neck (vascular neoplasm) can cause tinnitus and other symptoms.

- High blood pressure. Hypertension and factors that increase blood pressure, such as stress, alcohol and caffeine, can make tinnitus more noticeable.

- Turbulent blood flow. Narrowing or kinking in a neck artery (carotid artery) or vein in your neck (jugular vein) can cause turbulent, irregular blood flow, leading to tinnitus.

- Malformation of capillaries. A condition called arteriovenous malformation (AVM), abnormal connections between arteries and veins, can result in tinnitus. This type of tinnitus generally occurs in only one ear.

Medications that can cause tinnitus

A number of medications may cause or worsen tinnitus. Generally, the higher the dose of these medications, the worse tinnitus becomes. Often the unwanted noise disappears when you stop using these drugs. Medications known to cause or worsen tinnitus include:

- Antibiotics, including polymyxin B, erythromycin, vancomycin and neomycin

- Cancer medications, including mechlorethamine and vincristine

- Water pills (diuretics), such as bumetanide, ethacrynic acid or furosemide

- Quinine medications used for malaria or other health conditions

- Certain antidepressants may worsen tinnitus

- Aspirin taken in uncommonly high doses (usually 12 or more a day)

Risk factors for Tinnitus

Anyone can experience tinnitus, but these factors may increase your risk:

- Loud noise exposure. Prolonged exposure to loud noise can damage the tiny sensory hair cells in your ear that transmit sound to your brain. People who work in noisy environments — such as factory and construction workers, musicians, and soldiers — are particularly at risk.

- Age. As you age, the number of functioning nerve fibers in your ears declines, possibly causing hearing problems often associated with tinnitus.

- Gender. Men are more likely to experience tinnitus.

- Smoking. Smokers have a higher risk of developing tinnitus.

- Cardiovascular problems. Conditions that affect your blood flow, such as high blood pressure or narrowed arteries (atherosclerosis), can increase your risk of tinnitus.

Complications of Tinnitus

Tinnitus can significantly affect quality of life. Although it affects people differently, if you have tinnitus, you also may experience:

- Fatigue

- Stress

- Sleep problems

- Trouble concentrating

- Memory problems

- Depression

- Anxiety and irritability

Treating these linked conditions may not affect tinnitus directly, but it can help you feel better.

Prevention of Tinnitus

In many cases, tinnitus is the result of something that can’t be prevented. However, some precautions can help prevent certain kinds of tinnitus.

- Use hearing protection. Over time, exposure to loud noise can damage the nerves in the ears, causing hearing loss and tinnitus. If you use chain saws, are a musician, work in an industry that uses loud machinery or use firearms (especially pistols or shotguns), always wear over-the-ear hearing protection.

- Turn down the volume. Long-term exposure to amplified music with no ear protection or listening to music at very high volume through headphones can cause hearing loss and tinnitus.

- Take care of your cardiovascular health. Regular exercise, eating right and taking other steps to keep your blood vessels healthy can help prevent tinnitus linked to blood vessel disorders.

Diagnosis of Tinnitus

Your doctor will examine your ears, head and neck to look for possible causes of tinnitus. Tests include:

- Hearing (audiological) exam. As part of the test, you’ll sit in a soundproof room wearing earphones through which will be played specific sounds into one ear at a time. You’ll indicate when you can hear the sound, and your results are compared with results considered normal for your age. This can help rule out or identify possible causes of tinnitus.

- Movement. Your doctor may ask you to move your eyes, clench your jaw, or move your neck, arms and legs. If your tinnitus changes or worsens, it may help identify an underlying disorder that needs treatment.

- Imaging tests. Depending on the suspected cause of your tinnitus, you may need imaging tests such as CT or MRI scans.

The sounds you hear can help your doctor identify a possible underlying cause.

- Clicking. Muscle contractions in and around your ear can cause sharp clicking sounds that you hear in bursts. They may last from several seconds to a few minutes.

- Rushing or humming. Usually vascular in origin, you may notice sound fluctuations when you exercise or change positions, such as when you lie down or stand up.

- Heartbeat. Blood vessel problems, such as high blood pressure, an aneurysm or a tumor, and blockage of the ear canal or eustachian tube can amplify the sound of your heartbeat in your ears (pulsatile tinnitus).

- Low-pitched ringing. Conditions that can cause low-pitched ringing in one ear include Meniere’s disease. Tinnitus may become very loud before an attack of vertigo — a sense that you or your surroundings are spinning or moving.

- High-pitched ringing. Exposure to a very loud noise or a blow to the ear can cause a high-pitched ringing or buzzing that usually goes away after a few hours. However, if there’s hearing loss as well, tinnitus may be permanent. Long-term noise exposure, age-related hearing loss or medications can cause a continuous, high-pitched ringing in both ears. Acoustic neuroma can cause continuous, high-pitched ringing in one ear.

- Other sounds. Stiff inner ear bones (otosclerosis) can cause low-pitched tinnitus that may be continuous or may come and go. Earwax, foreign bodies or hairs in the ear canal can rub against the eardrum, causing a variety of sounds.

In many cases, the cause of tinnitus is never found. Your doctor can discuss with you steps you can take to reduce the severity of your tinnitus or to help you cope better with the noise.

Treatment of Tinnitus

Treating an underlying health condition

To treat your tinnitus, your doctor will first try to identify any underlying, treatable condition that may be associated with your symptoms. If tinnitus is due to a health condition, your doctor may be able to take steps that could reduce the noise. Examples include:

- Earwax removal. Removing impacted earwax can decrease tinnitus symptoms.

- Treating a blood vessel condition. Underlying vascular conditions may require medication, surgery or another treatment to address the problem.

- Changing your medication. If a medication you’re taking appears to be the cause of tinnitus, your doctor may recommend stopping or reducing the drug, or switching to a different medication.

Noise suppression

In some cases white noise may help suppress the sound so that it’s less bothersome. Your doctor may suggest using an electronic device to suppress the noise. Devices include:

- White noise machines. These devices, which produce simulated environmental sounds such as falling rain or ocean waves, are often an effective treatment for tinnitus. You may want to try a white noise machine with pillow speakers to help you sleep. Fans, humidifiers, dehumidifiers and air conditioners in the bedroom also may help cover the internal noise at night.

- Hearing aids. These can be especially helpful if you have hearing problems as well as tinnitus.

- Masking devices. Worn in the ear and similar to hearing aids, these devices produce a continuous, low-level white noise that suppresses tinnitus symptoms.

- Tinnitus retraining. A wearable device delivers individually programmed tonal music to mask the specific frequencies of the tinnitus you experience. Over time, this technique may accustom you to the tinnitus, thereby helping you not to focus on it. Counseling is often a component of tinnitus retraining.

Medications

Drugs can’t cure tinnitus, but in some cases they may help reduce the severity of symptoms or complications. Possible medications include:

- Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline and nortriptyline, have been used with some success. However, these medications are generally used for only severe tinnitus, as they can cause troublesome side effects, including dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation and heart problems.

- Alprazolam (Niravam, Xanax) may help reduce tinnitus symptoms, but side effects can include drowsiness and nausea. It can also become habit-forming.

Home remedies for Tinnitus

Often, tinnitus can’t be treated. Some people, however, get used to it and notice it less than they did at first. For many people, certain adjustments make the symptoms less bothersome. These tips may help:

- Avoid possible irritants. Reduce your exposure to things that may make your tinnitus worse. Common examples include loud noises, caffeine and nicotine.

- Cover up the noise. In a quiet setting, a fan, soft music or low-volume radio static may help mask the noise from tinnitus.

- Manage stress. Stress can make tinnitus worse. Stress management, whether through relaxation therapy, biofeedback or exercise, may provide some relief.

- Reduce your alcohol consumption. Alcohol increases the force of your blood by dilating your blood vessels, causing greater blood flow, especially in the inner ear area.

Alternative medicine

There’s little evidence that alternative medicine treatments work for tinnitus. However, some alternative therapies that have been tried for tinnitus include:

- Acupuncture

- Hypnosis

- Ginkgo biloba

- Zinc supplements

- B vitamins

Neuromodulation using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a painless, noninvasive therapy that has been successful in reducing tinnitus symptoms for some people. Currently, TMS is utilized more commonly in Europe and in some trials in the U.S. It is still to be determined which patients might benefit from such treatments.

Coping and support for Tinnitus

Tinnitus doesn’t always improve or completely go away with treatment. Here are some suggestions to help you cope:

- Counseling. A licensed therapist or psychologist can help you learn coping techniques to make tinnitus symptoms less bothersome. Counseling can also help with other problems often linked to tinnitus, including anxiety and depression.

- Support groups. Sharing your experience with others who have tinnitus may be helpful. There are tinnitus groups that meet in person, as well as Internet forums. To ensure the information you get in the group is accurate, it’s best to choose a group facilitated by a physician, audiologist or other qualified health professional.

- Education. Learning as much as you can about tinnitus and ways to alleviate symptoms can help. And just understanding tinnitus better makes it less bothersome for some people.

Balance problems

Balance problems are conditions that make you feel unsteady or dizzy. If you are standing, sitting or lying down, you might feel as if you are moving, spinning or floating. If you are walking, you might suddenly feel as if you are tipping over or generally unsteady.

Many body systems — including your muscles, bones, joints, vision, the balance organ in the inner ear, nerves, heart and blood vessels — must work normally for you to have normal balance. When these systems aren’t functioning well, you can experience balance problems.

Many medical conditions can cause balance problems. However, most balance problems result from issues in your balance end-organ in the inner ear (vestibular system).

Symptoms of balance problem

Signs and symptoms of balance problems include:

- Sense of motion or spinning (vertigo)

- Feeling of faintness (presyncope)

- Loss of balance (disequilibrium)

- Dizziness

Causes of balance problem

Balance problems can be caused by several different conditions. The cause of balance problems is usually related to the specific sign or symptom.

Sense of motion or spinning (vertigo)

Vertigo can be associated with many conditions, including:

- Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). BPPV occurs when calcium crystals in your inner ear — which help control your balance — are dislodged from their normal position and move elsewhere in the inner ear. BPPV is the most common cause of vertigo. You might experience a spinning sensation when turning in bed or tilting your head back to look up.

- Meniere’s disease. In addition to sudden and severe vertigo, Meniere’s disease can cause fluctuating hearing loss and buzzing, ringing or a feeling of fullness in your ear. The cause of Meniere’s disease isn’t fully known. Meniere’s disease is rare and typically develops in people who are between the ages of 20 and 60.

- Migraine. Dizziness and sensitivity to motion (vestibular migraine) can occur due to migraine headache. Migraine is a common cause of dizziness.

- Acoustic neuroma. This noncancerous (benign), slow-growing tumor develops on a nerve that affects your hearing and balance. You might experience dizziness or loss of balance, but the most common symptoms are hearing loss and ringing in your ear. Acoustic neuroma is a rare condition.

- Vestibular neuritis. This inflammatory disorder, probably caused by a virus, can affect the nerves in the balance portion of your inner ear. Symptoms are often severe and persistent, and include nausea and difficulty walking. Symptoms can last several days and gradually improve on their own.

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Also known as herpes zoster otitis, this condition occurs when a shingles infection affects the facial nerve near one of your ears. You might experience vertigo, ear pain and hearing loss.

- Head injury. You might experience vertigo due to a concussion or other head injury.

- Motion sickness. You might experience dizziness in boats, cars and airplanes, or on amusement park rides.

- Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. This disorder occurs frequently with other types of vertigo. Symptoms include unsteadiness or a sensation of motion in your head. Symptoms often worsen when you watch objects move, when you read, or when you are in a visually complex environment such as a shopping mall.

Feeling of faintness (presyncope)

Presyncope can be associated with:

- Orthostatic hypotension (postural hypotension). Standing or sitting up too quickly can cause some people to experience a significant drop in their blood pressure, resulting in presyncope.

- Cardiovascular disease. Abnormal heart rhythms (heart arrhythmia), narrowed or blocked blood vessels, a thickened heart muscle (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), or a decrease in blood volume can reduce blood flow and cause presyncope.

Loss of balance (disequilibrium)

Losing your balance while walking, or feeling imbalanced, can result from:

- Vestibular problems. Abnormalities in your inner ear can cause a sensation of a floating or heavy head, and unsteadiness in the dark.

- Nerve damage to your legs (peripheral neuropathy). The damage can lead to difficulties with walking.

- Joint, muscle or vision problems. Muscle weakness and unstable joints can contribute to your loss of balance. Difficulties with eyesight also can lead to disequilibrium.

- Medications. Disequilibrium can be a side effect of medications.

- Certain neurologic conditions. These include cervical spondylosis and Parkinson’s disease.

Dizziness

A sense of dizziness or lightheadedness can result from:

- Inner ear problems. Abnormalities of the vestibular system can lead to a sensation of floating or other false sensation of motion.

- Psychiatric disorders. Depression (major depressive disorder), anxiety and other psychiatric disorders can cause dizziness.

- Abnormally rapid breathing (hyperventilation). This condition often accompanies anxiety disorders and may cause lightheadedness.

- Medications. Lightheadedness can be a side effect of medications.

Diagnosis of balance problem

Your doctor will start by reviewing your medical history and conducting a physical and neurological examination.

To determine if your symptoms are caused by problems in the balance function in your inner ear, your doctor is likely to recommend tests. They might include:

- Hearing tests. Difficulties with hearing are frequently associated with balance problems.

- Posturography test. Wearing a safety harness, you try to remain standing on a moving platform. A posturography test indicates which parts of your balance system you rely on most.

- Electronystagmography and video nystagmography. Both tests record your eye movements, which play a role in vestibular function and balance. Electronystagmography uses electrodes and video nystagmography uses small cameras to record eye movements.

- Rotary chair test. Your eye movements are analyzed while you sit in a computer-controlled chair that moves slowly in one place in a circle.

- Dix-Hallpike maneuver. Your doctor carefully turns your head in different positions while watching your eye movements to determine if you have a false sense of motion or spinning.

- Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials test. Sensor pads attached to your neck and forehead and under your eyes measure tiny changes in muscle contractions in reaction to sounds.

- Imaging tests. MRI and CT scans can determine if underlying medical conditions might be causing your balance problem.

- Blood pressure and heart rate tests. Your blood pressure might be checked when sitting and then after standing for 2 to 3 minutes to determine if you have significant drops in blood pressure. Your heart rate might be checked when standing to help determine if a heart condition is causing your symptoms.

Treatment of balance problem

Treatment depends on the cause of your balance problems. Your treatment may include:

- Balance retraining exercises (vestibular rehabilitation). Therapists trained in balance problems design a customized program of balance retraining and exercises. Therapy can help you compensate for imbalance, adapt to less balance and maintain physical activity. To prevent falls, your therapist might recommend a balance aid, such as a cane, and ways to reduce your risk of falls in your home.

- Positioning procedures. If you have BPPV, a therapist might conduct a procedure (canalith repositioning) that clears particles out of your inner ear and deposits them into a different area of your ear. The procedure involves maneuvering the position of your head.

- Diet and lifestyle changes. If you have Meniere’s disease or migraine headaches, dietary changes are often suggested that can ease symptoms. If you experience orthostatic hypotension, you might need to drink more fluids or wear compressive stockings.

- Medications. If you have severe vertigo that lasts hours or days, you might be prescribed medications that can control dizziness and vomiting.

- Surgery. If you have Meniere’s disease or acoustic neuroma, your treatment team may recommend surgery. Stereotactic radiosurgery might be an option for some people with acoustic neuroma. This procedure delivers radiation precisely to your tumor and doesn’t require an incision.

What is hearing loss ?

The ear can be divided into three parts:

- The external ear includes the pinna (outer, visible ear) and the ear canal

- The middle ear includes the tympanic membrane (ear drum) and the ossicles (middle ear bones)

- The inner ear, which includes the cochlea (organ of hearing) and vestibule (organ of balance)

Sound waves enter the ear canal and cause a vibration of the tympanic membrane (ear drum) which is then passed through three tiny bones behind the ear drum in the middle ear space: the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil) and stapes (stirrup). The sound vibrations in the ossicles are then transmitted to the nerves and fluids in the cochlea (inner ear), which generates a nerve impulse that passes along the auditory nerve to the brain.

What are the types of hearing loss ?

Hearing loss can be divided into two types:

- Conductive Hearing Loss, which is essentially a mechanical problem with the conduction of sound vibrations, and

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss, a problem with the generation and/or transmission of nerve impulses from the inner ear to the brain.

- Mixed hearing loss refers to a combination of these two types.

The preliminary classification of hearing loss as conductive or sensorineural can be determined by a physician using a tuning fork in the office. A formal audiogram, or hearing test, is the best way to determine the type and degree of hearing loss. The distinction between these two types of hearing loss is important because many cases of conductive hearing loss can be improved with medical or surgical intervention. An otolaryngologist, also called an Ear Nose and Throat or ENT doctor, can determine the specific diagnosis and treatments for either type of hearing loss and perform surgical treatments, if necessary.

What can cause Conductive Hearing Loss ?

Conductive hearing loss may result from diseases that affect the external ear or middle ear structures. Some of the causes of conductive hearing loss include:

Problems with the External Ear

- Cerumen (ear wax) obstruction: Ear wax can be identified by a medical examination and can usually be removed quickly. This condition may actually be aggravated by cotton tipped applicators (Q-tips) that many patients use in an attempt to clean their ears.

- Otitis Externa: Often referred to as “swimmer’s ear”, an infection of the ear canal may be related to water exposure. Although the most common symptoms of otitis externa are pain and tenderness of the ear, conductive hearing loss can also occur if there is severe swelling of the ear canal.

- Foreign body in Ear Canal: This is also readily identified on examination and can usually be cleared in the office. Occasionally, a brief anesthesia is required for this procedure in children. Common foreign bodies include beads and beans in children and cotton or the tips of cotton-tipped applicators in adults. Uncommonly, the foreign object is a live bug such as a cockroach which can cause itching, pain and noise.

- Bony lesions of Ear Canal: These are benign growths of bone along the walls of the ear canal resulting in a narrowing of the ear canal which may then lead to frequent obstruction from a small amount of wax or water. These bony lesions can generally be managed with vigilant cleaning of ear wax to prevent obstruction. In rare cases these lesions require surgical removal.

- Atresia of the Ear Canal: Complete malformation of the external ear canal is called atresia. It may be seen along with complete or partial malformation of the pinna (outer ear) and is noted at birth. It is rarely associated with other congenital abnormalities and is most often only on one side (unilateral). Management of congenital aural atresia is complex. Surgical treatment may be beneficial to either reconstruct the ear canal in select cases or to implant a device that vibrates the bone of the ear directly.

Problems with the Middle Ear structures