Vallecular cysts

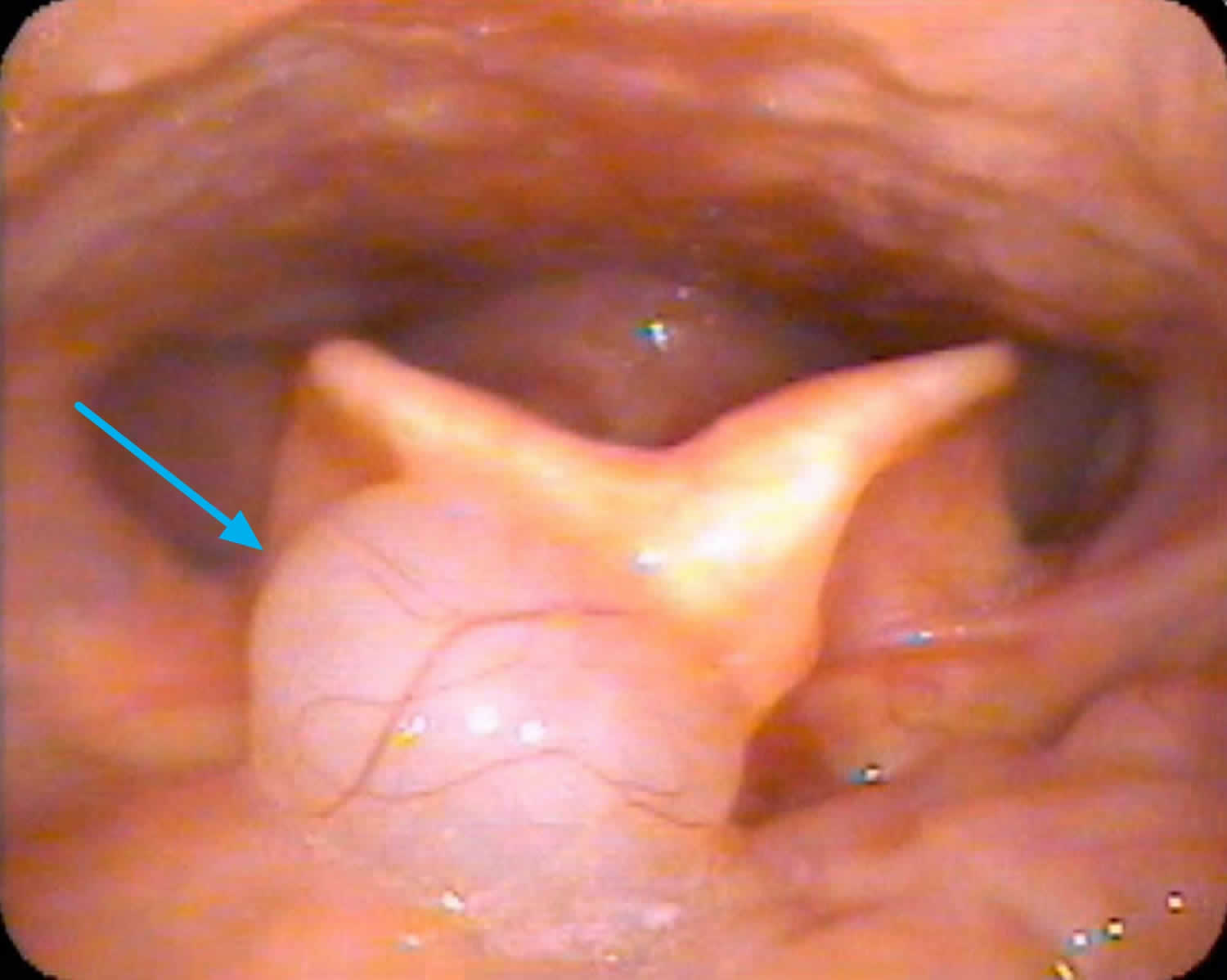

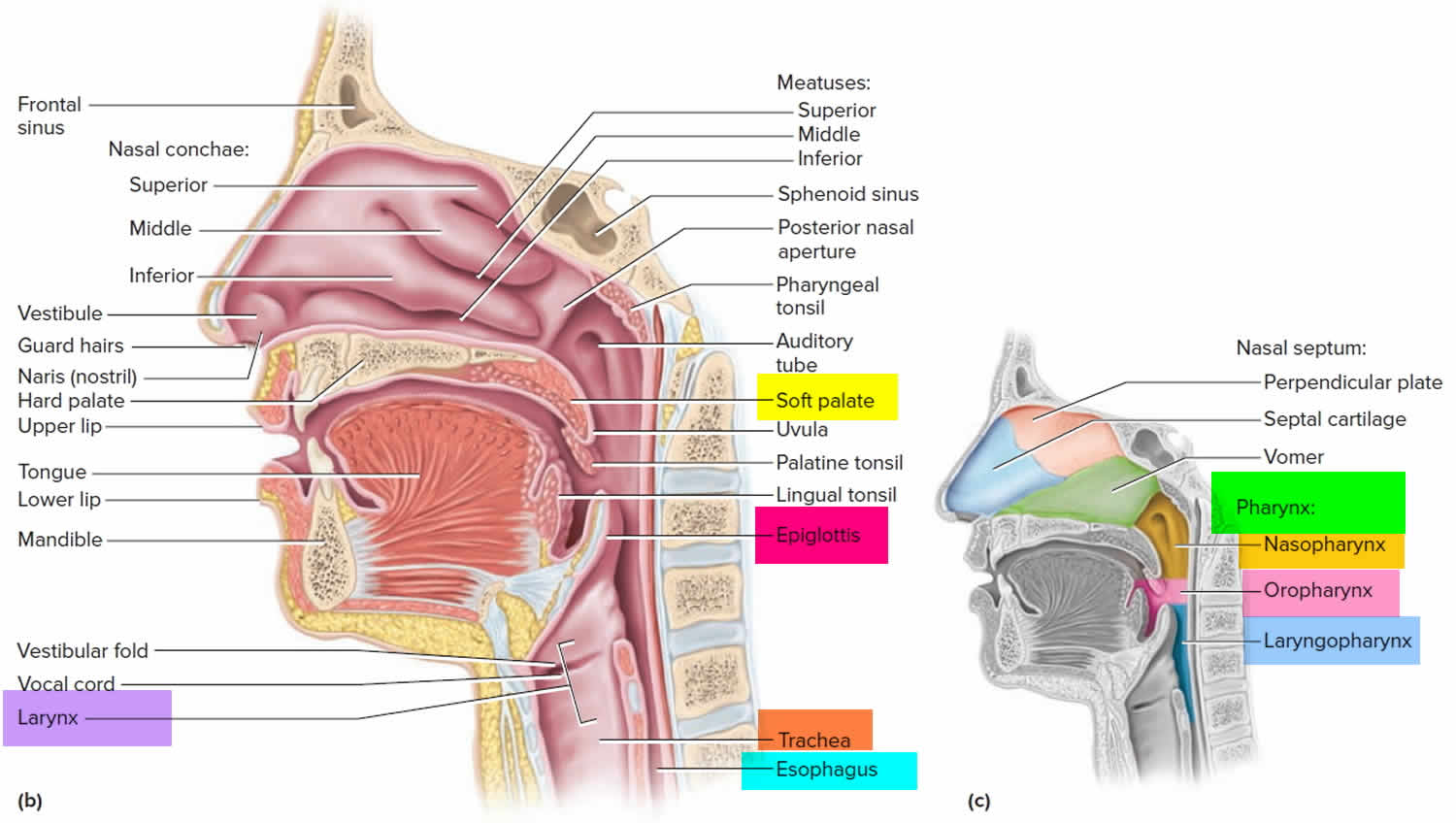

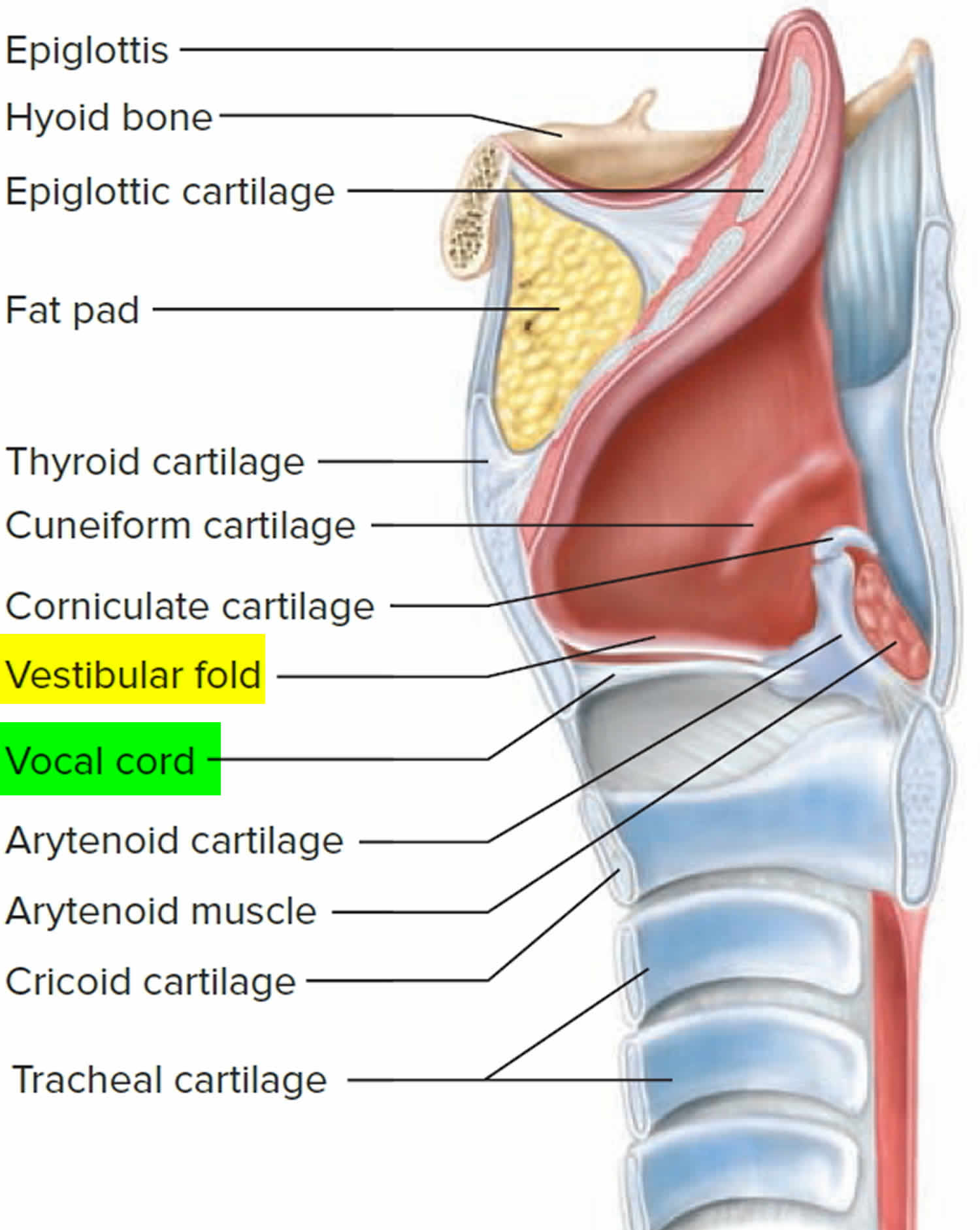

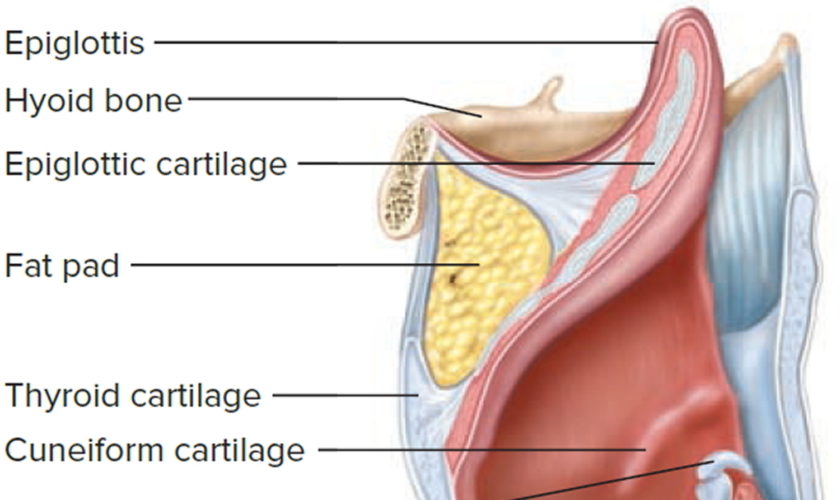

Vallecular cysts also called epiglottic mucus retention cysts or base of tongue cysts, are benign retention cysts of the minor salivary glands that are typically present at birth in the tongue base of affected infants 1. The commonest site for vallecular cysts is the lingual surface of epiglottis accounting for 10.5% to 20.1% of all laryngeal cysts 2. Vallecular cysts distort the epiglottis when they increase in size and eventually fill the vallecula. The vallecula is the depression behind the root of the tongue between the median and lateral epiglottic folds on each side 3.

The incidence of vallecular cysts on laryngoscopy has been reported as 1 in 1,250 to 1 in 4,200, but the true incidence is difficult to estimate 4.

Vallecular cyst is a rare cause of upper airway obstruction in infants and children and are typically not associated with other anomalies or syndromes. Presentation like acute stridor with near fatal respiratory distress is extremely rare. In infants and children, vallecular cysts present most commonly with stridor and feeding difficulty but may cause life-threatening airway obstruction 5. In adults, most vallecular cysts are asymptomatic but may present with sensation of a lump in the throat (globus), voice change, difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), painful swallowing (odynophagia) or shortness of breath (dyspnea) 6. Vallecular cysts may also be discovered during administration of anesthesia, where they may obscure the view of the glottis and cause difficult endotracheal intubation 7. In adults, vallecular cysts are more common but less dangerous. The peak incidence is in the fifth decade of life, and the majority of cysts occur in men 6.

Some believe that the vallecular cyst develops because of an obstruction of a minor salivary gland when the duct of a mucous gland or lingual tonsillar crypt becomes obstructed and dilates 8, while others believe that the vallecular cyst is a variant of a thyroglossal duct cyst. Vallecular cysts have therefore been classified as ductal cysts, retention cysts, and lymphoepithelial cysts and are caused by inflammation, irritation, or trauma 6.

Infants with vallecular cysts are considered to be at risk of airway obstruction and death 8. Therefore, all such cysts in infants and children should be removed surgically, with marsupialization via carbon dioxide laser (CO2 laser) or electrocautery being the most commonly used method 9. Vallecular cyst is commonly managed using microlaryngoscope and specialized instruments.

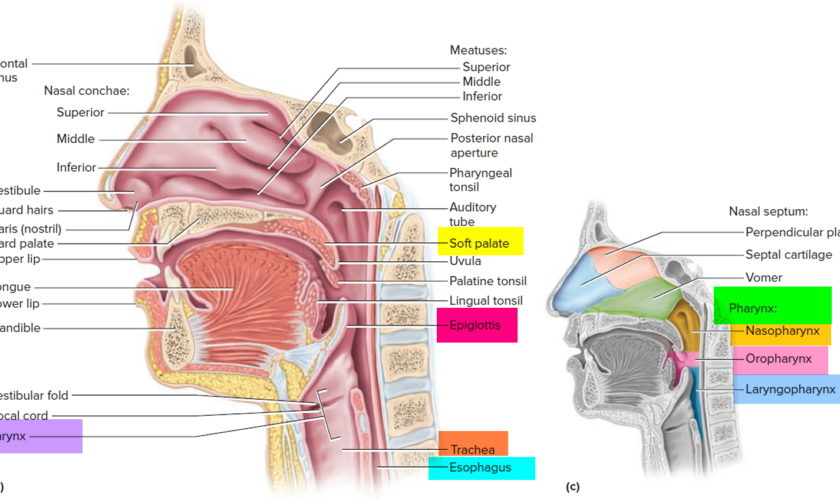

Figure 1. Vallecular cyst

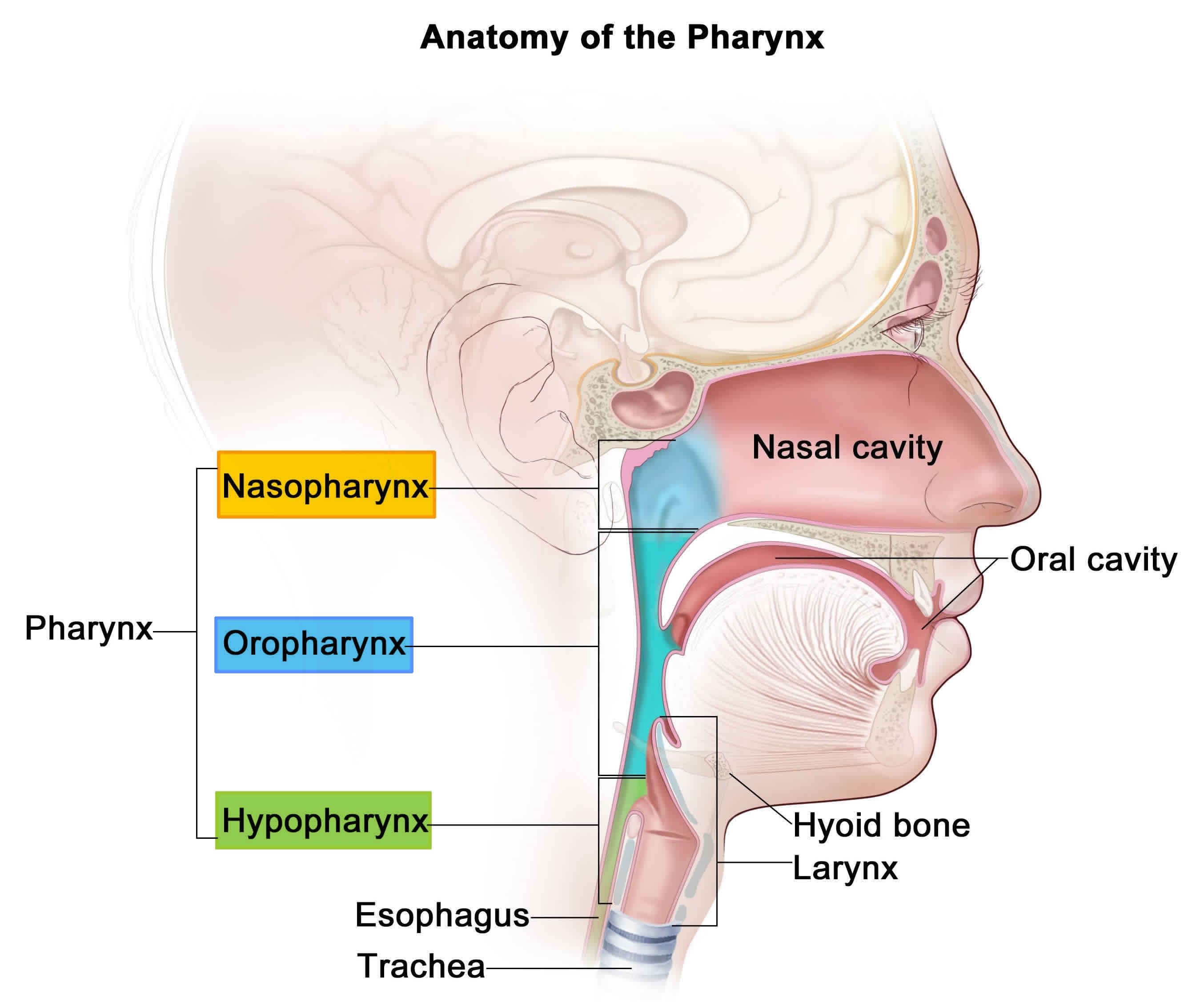

Figure 2. Pharynx and larynx anatomy

Vallecular cyst causes

Vallecular cysts are thought to be secondary cysts formed from either ductal obstruction of mucous glands or cystic tongue lesions developed from misplaced embryonic remnants of the foregut 10.

Vallecular cysts commonly arise from the lingual surface of the epiglottis and are unilocular cysts containing clear sterile fluid arising from the lingular surface of the epiglottis 11.

Histologically vallecular cysts are lined by non-keratinizing squamous or respiratory epithelium with mucous glands with an external lining of squamous epithelium 12.

Vallecular cyst symptoms

Vallecular cysts may present with diverse symptoms affecting the voice, airway, and swallowing. Patients with vallecular cysts often have similar symptoms/signs as those with laryngomalacia.

- Inspiratory stridor is usually present at birth (noisy inhale)

- Feeding difficulties

- Minimal, moderate or severe respiratory distress

Vallecular cysts can cause feeding difficulties due to upper airway obstruction and pressure at the laryngeal inlet 12.

Nearly two-thirds of vallecular cysts are asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally on routine laryngeal examination 6.

Vallecular cyst diagnosis

If the vallecular cysts are very small, diagnosis may be delayed until the child is older and begins to complain of swallowing difficulties. In the majority of patients, vallecular cyst is large enough to bring the patient to the attention of the otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat specialist) who can then confirm the diagnosis using flexible laryngoscopy. Imaging (CT scans, X-rays, etc.) is not required for patients with vallecular cysts.

Antenatal diagnosis of vallecular cyst has been reported by Cuillier et al. 11 in a 28 week gestation fetus with polyhydramnios using MRI following a suspicion on ultrasound imaging. In this case, polyhydramnios was secondary to partial obstruction of the esophagus due to mass effect. Vallecular cyst was noted at birth to be filling the oral cavity and needed cyst aspiration followed by endotracheal intubation due to airway obstruction. Prenatal diagnosis of a significant vallecular cyst gives the window of opportunity for parental counseling and multidisciplinary planning for intervention after birth. In suspected cases with severe airway obstruction diagnosed prenatally, an ex-utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure may be planned 13.

Aero-digestive evaluation

Infants with vallecular cysts need to be evaluated for both airway and feeding issues. Management of the airway often requires a combination of supportive, medical and surgical care. Feeding and swallowing issues are common in children with vallecular cysts and often need to be addressed by speech pathologists and gastroenterology specialists.

Vallecular cyst treatment

Surgical removal is the treatment of choice for vallecular cyst 14. Surgery is performed endoscopically. Once the airway is secured with an endotracheal tube, this may be performed either by aspiration, marsupialization (deroofing) or excision using either microlaryngeal instruments or a laser 15. Marsupialization via coblation has been used to treat vallecular cyst. Coblation involves the use of radiofrequency and normal saline to create an isoelectric field of sodium and chloride ions moving at high speeds that have sufficient energy to breakdown tissues 16. This modality has the advantages of a minimally invasive technique with reduced thermal damage, bleeding, tissue damage and postoperative recovery time 17. In general, simple aspiration of vallecular cyst is avoided due to the high risk of recurrence 18. Most reports show low recurrence rate of vallecular cyst after marsupialization. Li Y et al. 12 reported recurrence of vallecular cyst in 15% of cases in their center following marsupialization.

Patients generally do very well after surgery and most often resume normal diet with no breathing issues. Occasionally, patients may require some support for secondary laryngomalacia or reflux until the airway grows sufficiently. Recurrence of the cyst is very rare following treatment.

Vallecular cyst treatment options

Surgical treatment for vallecular cysts in infants includes aspiration, marsupialization (deroofing) and excision. The surgical approach is transoral under direct vision with or without a microlaryngoscope or using a microlaryngoscope with a camera assembly 19. The various tools used for this purpose include direct electrocautery, carbon dioxide laser (CO2 laser) or microlarygngoscopic instruments.

The use of the carbon dioxide laser (CO2 laser) for surgery of the vocal fold is a subject of controversy. Many prefer to avoid it, for although the cutting beam is reasonably precise, it is hypothesized that the tissue reaction is somewhat unpredictable, probably because of the emitted heat. The alternative is microscopic instruments. Although they are more technically difficult to use, they offer equivalent accuracy and perhaps less potential for inadvertent damage and scarring.

Suzuki et al. 19 reported a negligible recurrence rate after marsupialization of vallecular cysts as compared to complete excision. Complete excision is more invasive and there is the possibility of bleeding and postoperative residual scarring. Hence, marsupialization is the preferred treatment of vallecular cysts.

The same study recommends that aspiration should be attempted only as an initial maneuver in cases of difficult intubation and not as definitive treatment due to high rates of recurrence.

Da Vinci robot-assisted excision of a vallecular cyst was reported recently by McLeod et al. 20 and further research is needed to explore this modality of treatment.

Excision of cyst using a tonsillar snare has also been reported as an easy and cost-effective method of treatment 21.

Conventional laparoscopic instruments used were a 4 mm 0-degree telescope; 3 mm hook electrocautery and Maryland forceps. These give very good vision during surgery. The use of long instruments (approximately 33 cm) permits easy accessibility and maneuverability to the deep oral cavity and avoids undue overlapping and fighting between instruments. The instruments are insulated along their length which prevents thermal injury to other structures in the oral cavity. Pediatric surgeons are used to operating with conventional laparoscopic instruments as against specialized instruments like microdebrider, microscissors, etc.

References- Romak JJ, Olsen SM, Koch CA, Ekbom DC. Bilateral vallecular cysts as a cause of Dysphagia: case report and literature review. Int J Otolaryngol. 2010;2010:697583. doi:10.1155/2010/697583 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3005807

- Parelkar SV, Patel JL, Sanghvi BV, et al. An Unusual Presentation of Vallecular Cyst with near Fatal Respiratory Distress and Management Using Conventional Laparoscopic Instruments. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2012;4(2):118-120. doi:10.4103/2006-8808.110257 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3673355

- De A, Don DM, Magee W 3rd, Ward SL. Vallecular cyst as a cause of obstructive sleep apnea in an infant. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(8):825-826. Published 2013 Aug 15. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2932 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3716675

- Mason DG, Wark KJ. Unexpected difficult intubation. Asymptomatic epiglottic cysts as a cause of upper airway obstruction during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1987;42(4):407–410.

- Berger G, Averbuch E, Zilka K, Berger R, Ophir D. Adult vallecular cyst: thirteen-year experience. Otolaryngology. 2008;138(3):321–327.

- Arens C, Glanz H, Kleinsasser O. Clinical and morphological aspects of laryngeal cysts. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 1997;254(9-10):430–436.

- Rivo J, Matot I. Asymptomatic vallecular cyst: airway management considerations. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2001;13(5):383–386.

- Gutiérrez JP, Berkowitz RG, Robertson CF. Vallecular cysts in newborns and young infants. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1999;27(4):282–285.

- Leuin S, Cunningham M, Volk MS, Hartnick C. Transhyoid approach to excision of recurrent vallecular pseudocysts. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):124–127.

- A.K. Lahiri, K.K. Somashekar, B. Wittkop, et al. Large vallecular masses; differential diagnosis and imaging features J Clin Imaging Sci, 8 (2018), p. 26, 10.4103/jcis.JCIS_15_18

- F. Cuillier, S. Samperiz, R. Testud, et al. Antenatal diagnosis and management of a vallecular cyst. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 20 (2002), pp. 623-626, 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00860.x

- Y. Li, A.L. Irace, N.D. Dombrowski, et al. Vallecular cyst in the pediatric population: evaluation and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 113 (2018), pp. 198-203, 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.07.040

- P.A. Jayagopi, S. Chandran, B. Sriram, K.T. Chang. Ex-utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure for giant fetal epignathus. Indian Pediatr, 52 (10) (2015), pp. 893-895, 10.1007/s13312-015-0740-9

- Congenital vallecular cyst causing severe inspiratory stridor in a newborn. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports Volume 59, August 2020, 101460 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2020.101460

- A.F. AlAbdulla. Congenital vallecular cyst causing airway compromise in a 2-month-old girl. Case Rep Med, 2015 (2015), Article 975859, 10.1155/2015/975859

- Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, Y. Ye, et al. Clinical efficacy of low-temperature radiofrequency ablation of pharyngolaryngeal cyst in 84 Chinese infants. Medicine (Baltim), 96 (44) (2017), Article e8237, 10.1097/MD.0000000000008237

- S. Gogia, S.K. Agarwal, A. Agarwal. Vallecular cyst in neonates: case series—a clinicosurgical insight vol. 2014, Case Rep Otolaryngol (2014), p. 764860, 10.1155/2014/764860

- M. Raftopulos, M. Soma, D. Lowinger, et al. Vallecular cysts: a differential diagnosis to consider for neonatal stridor and failure to thrive. JRSM Short Rep, 4 (4) (2013), p. 29, 10.1177/2042533313476689

- Suzuki J, Hashimoto S, Watanabe K, Takahashi K. Congenital vallecular cyst in an infant: Case report and review of 52 recent cases. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:1199–203.

- McLeod IK, Melder PC. Da Vinci robot-assisted excision of a vallecular cyst: A case report. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84:170–2.

- Bhandary S. Innovative Surgical Technique in the Management of Vallecular Cyst. Online J Health Allied Sci. 2003;3:2.