Uroflowmetry

Uroflowmetry is a simple, diagnostic screening procedure used to measures the flow rate of urine over time (urine speed and urine volume). Uroflowmetry tracks how fast urine flows, how much flows out, and how long it takes. It’s a diagnostic test to assess how well your urinary tract functions. Your doctor may suggest uroflowmetry if you have trouble urinating, or have a slow stream. Uroflowmetry test is noninvasive (the skin is not pierced), and may be used to assess bladder and sphincter function. Uroflowmetry measurements are performed in a health care provider’s office; no anesthesia is needed.

By measuring the average and top rates of urine flow, this test can show an obstruction in your urinary tract such as an enlarged prostate. When combined with the cystometrogram, uroflowmetry can help find problems like a weak bladder.

For uroflowmetry test, you should arrive at the doctor’s office with a fairly full bladder. If possible, do not urinate for a few hours before the test.

You will be asked to urinate privately into a special toilet that has a container for collecting the urine and a scale or a funnel connected to the electronic uroflowmeter. The equipment creates a graph that shows changes in urine flow rate from second to second so your doctor can see when the flow rate is the highest and how many seconds it takes to get there. This records information about your urine flow on a flow chart. The flow rate is calculated as milliliters (ml) of urine passed per second. Both average and top flow rates are measured.

Results of this test will be abnormal if the bladder muscles are weak or urine flow is blocked. Another approach to measuring flow rate is to record the time it takes to urinate into a special container that accurately measures the volume of urine.

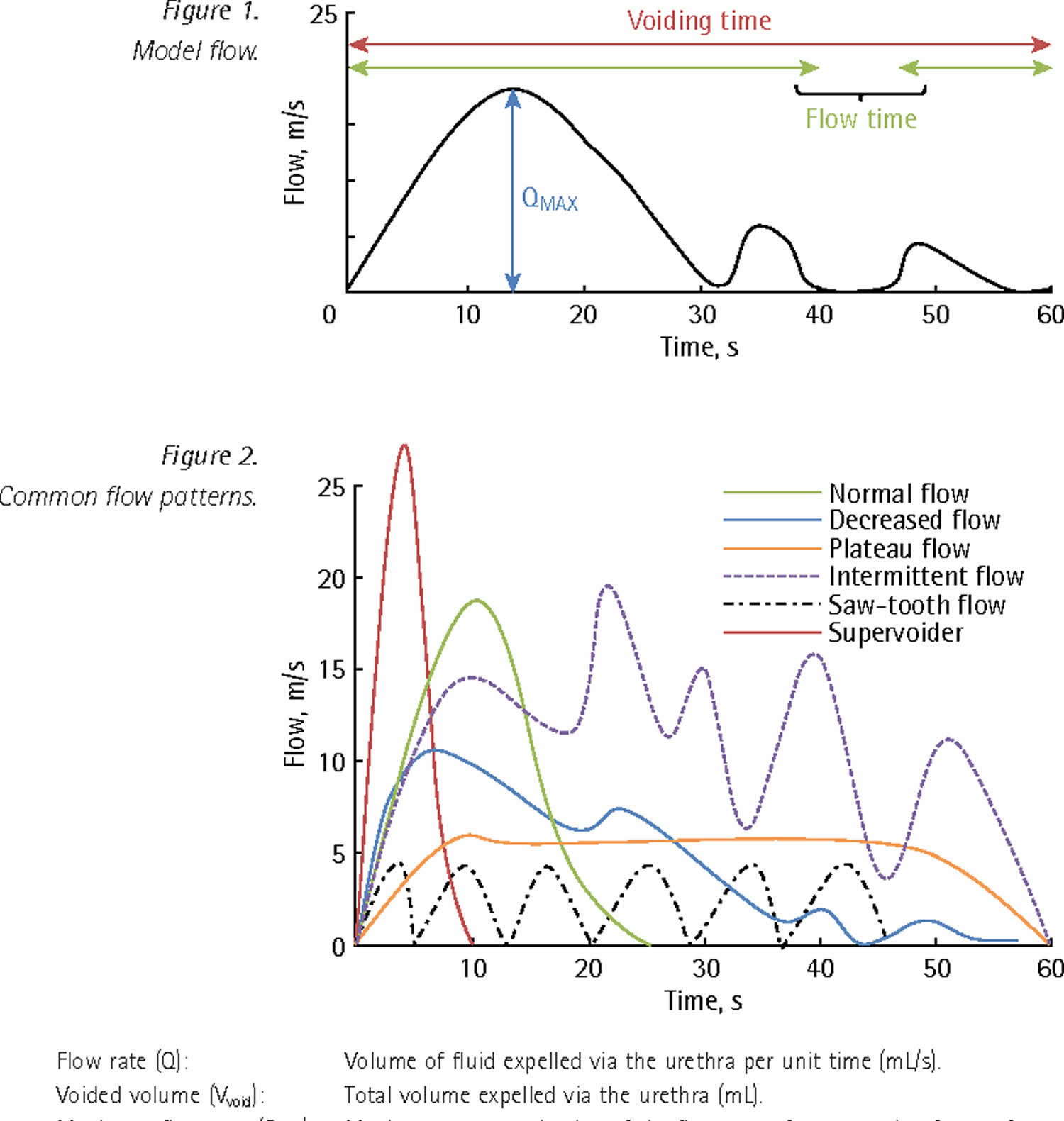

Common urine flow patterns:

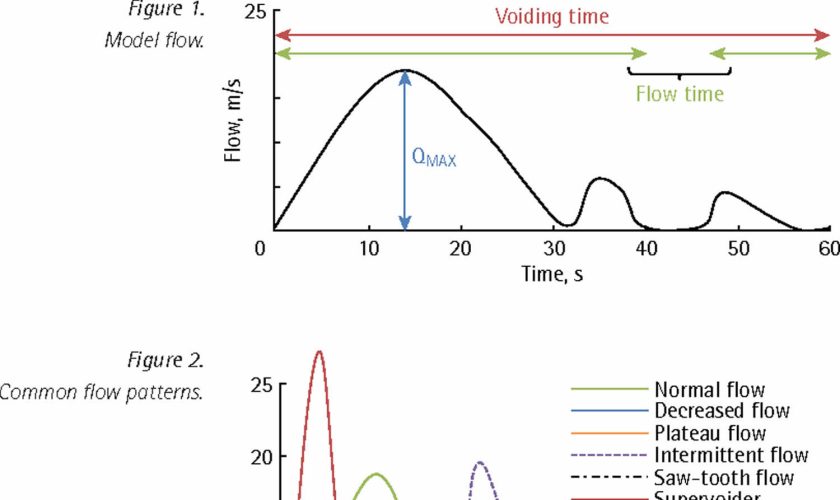

- Flow rate (Q): Volume of fluid expelled via the urethra per unit time (mL/s).

- Voided volume (Vvoid): Total volume expelled via the urethra (mL).

- Average flow rate (Qave): Voided volume divided by the flow time.

- Maximum flow rate (Qmax): Maximum measured value of the flow rate after correction for artefacts.

- Voiding time: Total duration of micturition (second).

- Flow time: Time over which measurable flow actually occurs.

- Time to maximum flow: Elapsed time from onset of flow to maximum flow.

The fastest flow rate, also known as maximum flow rate (Qmax), is used to understand if a block or obstruction is severe.

Your doctor will know your test results right away. Average results are based on your age and sex.

- Typically, urine flow rate from 10 ml to 21 ml per second. Women range closer to 15 ml to 18 ml per second.

- A slow or low flow rate may mean there is an obstruction at the bladder neck or in the urethra, an enlarged prostate, or a weak bladder.

- A fast or high flow rate may mean there are weak muscles around the urethra, or urinary incontinence problems.

You may be asked to take other tests to fully learn what’s going on for treatment. Your urologist will create a treatment plan based on test results and your health history.

Facts about urine:

- Adults pass about a quart and a half of urine each day, depending on the fluids and foods consumed.

- The volume of urine formed at night is about half that formed in the daytime.

- Normal urine is sterile. It contains fluids, salts, and waste products, but it is free of bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

- The tissues of the bladder are isolated from urine and toxic substances by a coating that discourages bacteria from attaching and growing on the bladder wall.

Figure 1. Uroflowmetry

How does the urinary system work?

The body takes nutrients from food and converts them to energy. After the body has taken the food components that it needs, waste products are left behind in the bowel and in the blood.

The urinary system helps the body to eliminate liquid waste called urea and keeps the chemicals, such as potassium and sodium, and water in balance. Urea is produced when foods containing protein, such as meat, poultry, and certain vegetables, are broken down in the body. Urea is carried in the bloodstream to the kidneys, where it is removed along with water and other wastes in the form of urine.

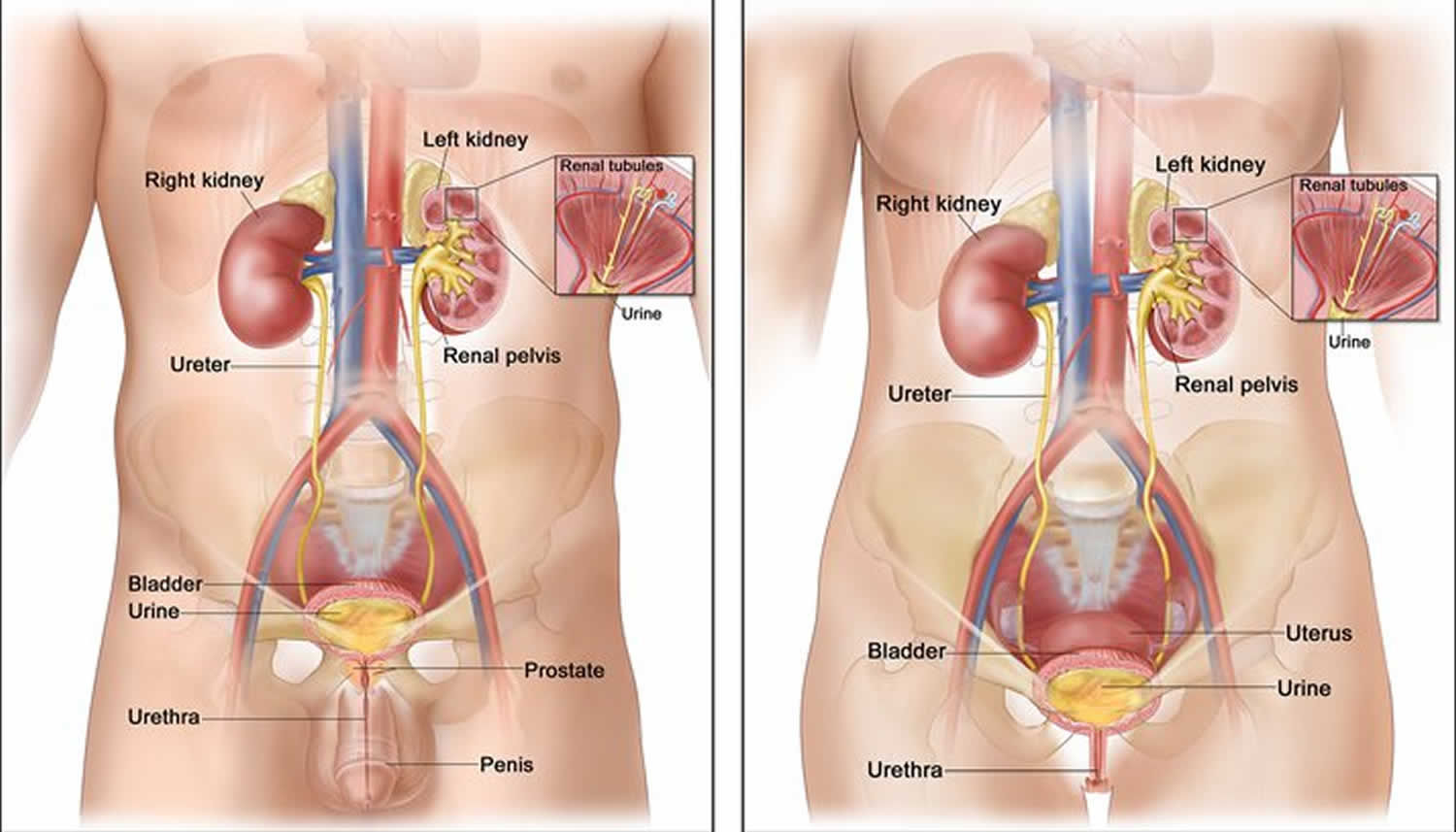

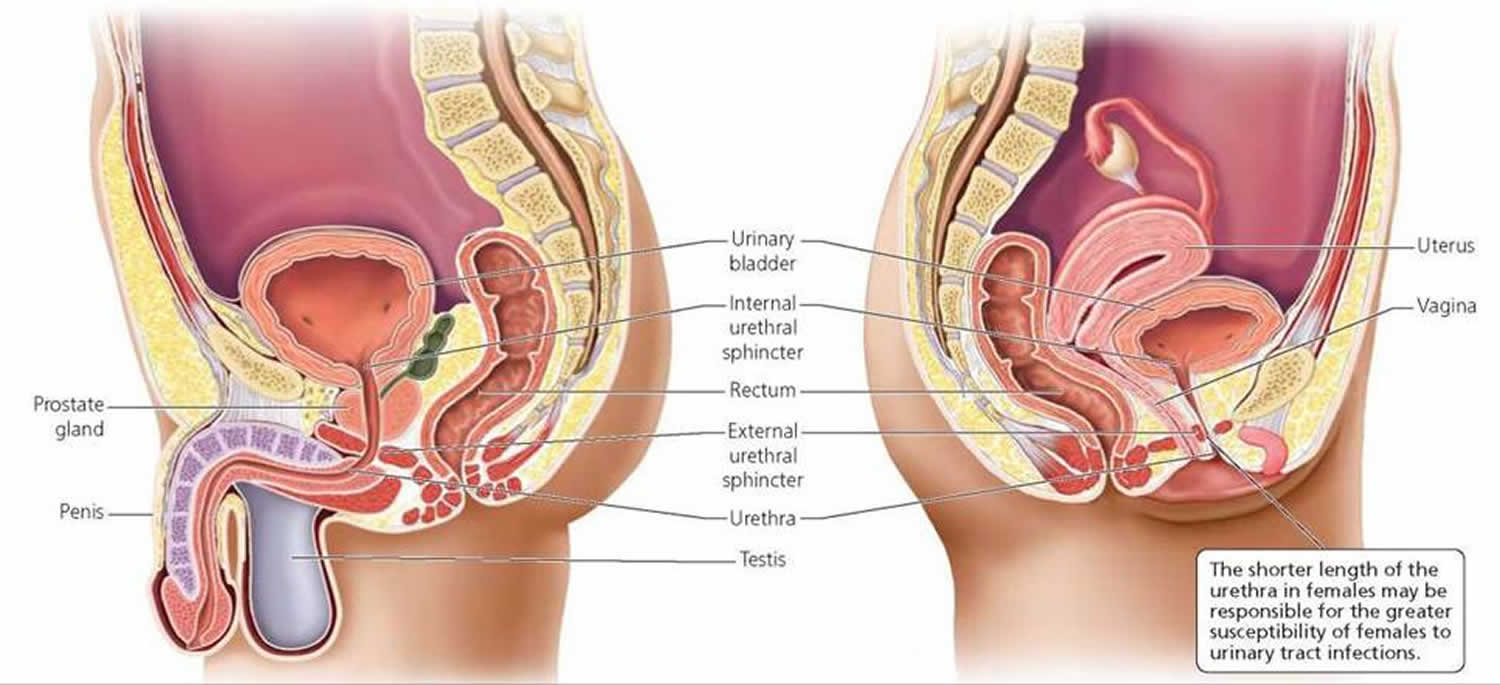

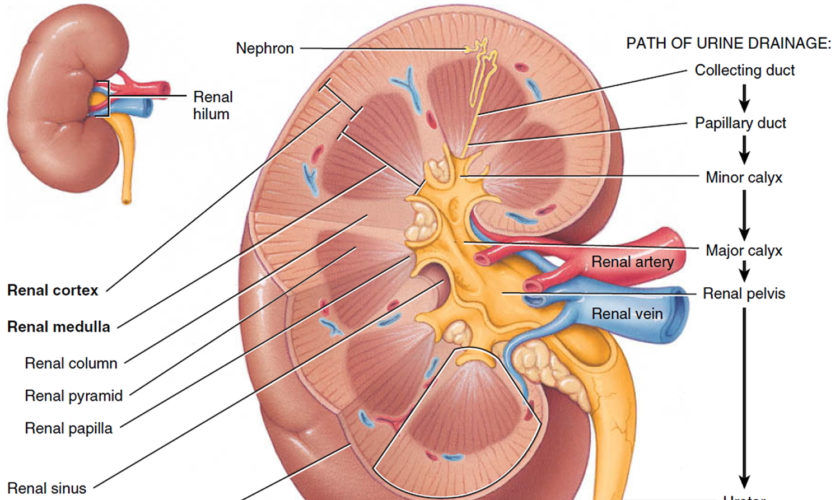

Urinary system parts and their functions:

- Two kidneys. This pair of purplish-brown organs is located below the ribs toward the middle of the back. Their function is to remove liquid waste from the blood in the form of urine, keep a stable balance of salts and other substances in the blood, and produce erythropoietin, a hormone that aids the formation of red blood cells. The kidneys also help to regulate blood pressure. The kidneys remove urea from the blood through tiny filtering units called nephrons. Each nephron consists of a ball formed of small blood capillaries, called a glomerulus, and a small tube called a renal tubule. Urea, together with water and other waste substances, forms the urine as it passes through the nephrons and down the renal tubules of the kidney.

- Two ureters. These narrow tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder. Muscles in the ureter walls continually tighten and relax forcing urine downward, away from the kidneys. If urine backs up, or is allowed to stand still, a kidney infection can develop. About every 10 to 15 seconds, small amounts of urine are emptied into the bladder from the ureters.

- Bladder. This triangle-shaped, hollow organ is located in the lower abdomen. It is held in place by ligaments that are attached to other organs and the pelvic bones. The bladder’s walls relax and expand to store urine, and contract and flatten to empty urine through the urethra. The typical healthy adult bladder can store up to two cups of urine for two to five hours.

- Two sphincter muscles. These circular muscles help keep urine from leaking by closing tightly like a rubber band around the opening of the bladder

- Nerves in the bladder. The nerves alert a person when it is time to urinate, or empty the bladder

- Urethra. This tube allows urine to pass outside the body

Figure 2. Urinary system and anatomy

Reasons for the uroflowmetry test

Uroflowmetry is a quick, simple diagnostic screening test that provides valuable feedback about the health of the lower urinary tract. It is commonly performed to determine if there is obstruction to normal urine outflow. Medical conditions that can alter the normal flow of urine include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Benign prostatic hypertrophy. A benign enlargement of the prostate gland that usually occurs in men over age 50. Enlargement of the prostate interferes with normal passage of urine from the bladder. If left untreated, the enlarged prostate can obstruct the bladder completely.

- Cancer of the prostate, or bladder tumor.

- Urinary incontinence. Involuntary release of urine from the bladder.

- Urinary blockage. Obstruction of the urinary tract can occur for many reasons along any part of the urinary tract from kidneys to urethra. Urinary obstruction can lead to a backflow of urine causing infection, scarring, or kidney failure if untreated.

- Neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Improper function of the bladder due to an alteration in the nervous system, such as a spinal cord lesion or injury.

- Frequent urinary tract infections.

Uroflowmetry may be performed in conjunction with other diagnostic procedures, such as cystometry, cystography, retrograde cystography, and cystoscopy.

There may be other reasons for your doctor to recommend uroflowmetry.

Urine flow rate test

Uroflowmetry is performed by having a person urinate into a special funnel that is connected to a measuring instrument. The measuring instrument calculates the amount of urine, rate of flow in seconds, and length of time until completion of the void. This information is converted into a graph and interpreted by a doctor. The information helps evaluate function of the lower urinary tract or help determine if there is an obstruction of normal urine outflow.

During normal urination, the initial urine stream starts slowly, but almost immediately speeds up until the bladder is nearly empty. The urine flow then slows again until the bladder is empty. In persons with a urinary tract obstruction, this pattern of flow is altered, and increases and decreases more gradually. The uroflowmeter graphs this information, taking into account the person’s gender and age. Depending on the results of the procedure, other tests may be recommended by your doctor.

Other related procedures that may be used to diagnose urinary outflow obstruction or lower urinary tract dysfunction include cystometry, cystography, retrograde cystography, and cystoscopy.

Before the urology flow rate test

- Your doctor will explain the procedure to you and offer you the opportunity to ask any questions that you might have about the procedure.

- Generally, no prior preparation, such as fasting or sedation, is required.

- You may be instructed to drink about four glasses of water several hours before the test is performed to ensure that your bladder is full. In addition, you should not empty your bladder before arriving for the procedure.

- If you are pregnant or suspect that you are pregnant, you should notify your doctor.

- Notify your doctor of all medications (prescription and over-the-counter) and herbal supplements that you are taking.

- Based on your medical condition, your doctor may request other specific preparation.

During the urology flow rate test

Uroflowmetry may be performed on an outpatient basis or as part of your stay in the hospital. Procedures may vary depending on your condition and your doctor’s practices.

Generally, uroflowmetry follows this process:

- You will be taken into the procedure area and instructed how to use the uroflowmetry device.

- When you are ready to urinate, you will press the flowmeter start button and count for five seconds before beginning urination.

- You will begin to urinate into the funnel device that is attached to the regular commode. The flowmeter will record information as you are urinating.

- You should not push or strain as you urinate. You should remain as still as possible.

- When you have finished urinating, you will count for five seconds and press the flowmeter button again.

- You should not put any toilet paper into the funnel device.

- The procedure will be concluded at this point. Depending on your specific medical condition, you may be asked to perform the test on several consecutive days.

After the urology flow rate test

Generally, there is no special type of care following uroflowmetry. However, your doctor may give you additional or alternate instructions after the procedure, depending on your particular situation.

Uroflowmetry normal flow

There is great variation in uroflowmetry parameters even in the non‐symptomatic population 1, although flow curves are generally repeatable for the same patient. In particular, there are no definitive ‘normal’ ranges for maximum flow rate (Qmax), although it decreases with age and voided volume (but not in a directly proportional manner). Males aged <40 years usually have a Qmax of >25 mL/s, and females usually have a Qmax of 5–10 mL/s more than males at a given bladder volume. Beware the ‘normal flow’ that in fact represents the effect of a compensatory increase in the voiding pressure generated by the detrusor in patients with bladder outlet obstruction 2.

Decreased urine flow

This is the most common abnormal flow trace seen in practice and is represented by a dampened curve with decreased Qmax and prolonged flow time. A significantly decreased Qmax (generally accepted as <15 mL/s) cannot be used to distinguish between BOO in men, outflow obstruction in women, and impaired detrusor contractility 6; in appropriate cases, formal multichannel urodynamic studies with concomitant measurements of flow and detrusor pressures are important to delineate between these conditions.

Despite the limitations, Qmax remains the single best non‐invasive urodynamic test to detect possible lower urinary tract obstruction. The test is also useful in some clinical situations to guide further evaluation to predict outcome after surgery and for preoperative counseling:

- Males with a Qmax above the threshold value of 15 mL/s (or 12 mL/s) 3 may have a poorer outcome after prostate surgery for presumed bladder outlet obstruction 4 and these men should be considered for formal urodynamics to arrive at a definite diagnosis and decrease treatment failures.

- Females undergoing mid‐urethral sling surgery with a Qmax of <15 mL/s at preoperative uroflowmetry are more likely to fail a trial of void after sling surgery 5.

Plateau urine flow

A long flow time, associated with a poor flow is typical of a stricture in the lower urinary tract. Another commonly encountered scenario is the patient with post‐radical prostatectomy incontinence. One should suspect an anastomotic stricture if this flow curve pattern is seen in the office during initial postoperative assessment. The patient should be considered for a cystoscopy with a view to treat the stricture as the next step in management, rather than referral for a formal urodynamic study as difficult catheterisation is commonly encountered.

Intermittent urine flow

This may be seen in patients who void with some abdominal straining due to bladder outlet obstruction or a poorly contractile detrusor, and is often superimposed on a decreased or plateauing curve pattern.

‘Saw‐tooth’ urine flow

Often pathogneumonic of detrusor‐sphincter‐dyssynergia, this curve should prompt urgent pressure‐flow studies to investigate high intravesical pressures that might damage the upper tracts.

‘Super‐voider’

This is seen after surgery for bladder outlet obstruction (e.g. TURP or urethroplasty), in patients with decreased urethral resistance (e.g. intrinsic urethral sphincter deficiency), or occasionally in those with detrusor overactivity. It may be considered ‘normal’ if there are no symptoms or signs to suggest underlying pathology, and is sometimes seen in young healthy female patients who may have a Qmax exceeding 40 mL/s.

‘Kicking the bucket’, and other artefacts

Urologists must be wary of artefacts and always compare the automated printout reading with the curve and clinical context. Smooth muscle physiology suggests that there should not be any abrupt spikes on a trace. A patient who accidentally kicks the flowmeter can appear to have a ‘normal’ Qmax. Other artefacts created by abdominal straining, squeezing the prepuce, or even variations in the direction of the urinary stream (within the funnel of the uroflowmeter) are common and urologists must recognise these.

Uroflowmetry procedure risks

Because uroflowmetry is a noninvasive procedure, it is safe for most persons. The test is usually done in privacy to ensure that the person voids in a natural setting.

There may be risks depending on your specific medical condition. Be sure to discuss any concerns with your doctor prior to the procedure.

Certain factors or conditions may interfere with the accuracy of uroflowmetry. These factors include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Straining with urination

- Body movement during urination

- Certain medications that affect bladder and sphincter muscle tone

- Wyndaele JJ. Normality in urodynamics studied in healthy adults. J Urology 1999; 161: 899–902.

- Jarvis, T.R., Chan, L. and Tse, V. (2012), PRACTICAL UROFLOWMETRY. BJU Int, 110: 28-29. doi:10.1111/bju.11617

- McLoughlin J, Gill KP, Abel PD, Williams G. Symptoms versus flow rates versus urodynamics in the selection of patients for prostatectomy. Br J Urol 1990; 66: 303–305.

- Jensen KM, Jorgensen JB, Mogensen P. Urodynamics in prostatism. I. Prognostic value of uroflowmetry. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1988; 22: 109–117.

- Wheeler TL, Richter HE, Greer WJ, Bowling CB, Redden DT, Varner RE. Predictors of success with postoperative voiding trials after a mid‐urethral sling procedure. J Urol 2008; 179: 600–604.