Cerebral vasculitis

Cerebral vasculitis also called central nervous system vasculitis, cerebral angiitis or primary angiitis of the central nervous system, is vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessel wall) involving the brain and occasionally the spinal cord without any evidence of systemic vasculitis 1. A serious condition, cerebral vasculitis can block the vessels that supply the brain and spinal cord, causing potentially life-threatening complications such as loss of brain function, or stroke. Cerebral vasculitis affects all of the vessels: very small blood vessels (capillaries), medium-size blood vessels (arterioles and venules), or large blood vessels (arteries and veins). If blood flow in a vessel with vasculitis is reduced or stopped, the parts of the body that receive blood from that vessel begins to die.

Cerebral vasculitis is typically categorized as “primary” and “secondary”:

- Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is vasculitis confined specifically to the brain and spinal cord, which make up the central nervous system. It is not associated with any other systemic (affecting the whole body) disease.

- Secondary cerebral vasculitis usually occurs in the presence of other autoimmune diseases such systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, or rheumatoid arthritis; systemic forms of vasculitis, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, or Behcet’s syndrome; or viral or bacterial infections.

Diagnosis of this condition can be challenging because a number of other diseases and infections have similar symptoms. Once diagnosed, CNS vasculitis is typically treated with corticosteroids such as prednisone, used in combination with medications that suppress the immune system. Even with effective treatment, relapse of CNS vasculitis is common, so ongoing medical follow-up is important.

Clinical manifestations of cerebral vasculitis at the time of diagnosis are non-specific with various presenting symptoms. A headache has been the most common presenting symptom in the majority of the cerebral vasculitis cases. Other symptoms include focal neurological deficits including hemiparesis, aphasia, numbness, visual symptoms, ataxia, among others 2.

In general, cerebral vasculitis is considered rare. Studies which describe the exact epidemiology of this rare disorder have not been done, and the only available data shows an annual incidence rate of 2.4 cases per 1 million person-years 1. In the case of cerebral vasculitis, the disorder can affect people of all ages but generally peaks around age 50. Cerebral vasculitis has also been found to have an equal distribution among both the sexes 1.

Cerebral vasculitis causes

The exact cause and pathogenesis of cerebral vasculitis are unknown. Vasculitis is classified as an autoimmune disorder—a disease which occurs when the body’s natural defense system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues. Researchers believe an infection may contribute to the onset of cerebral vasculitis, infectious agents such as varicella zoster virus have been postulated as one of the triggers. Environmental and genetic factors may play a role as well.

Other proposed causes include the following:

- Bacterial triggers including Mycoplasma, Rickettsia, Treponema

- Viral infections including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus, among others

- Connective tissue disorders and systemic vasculitides including Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Churg-Strauss syndrome, Behcet syndrome, Sjogren syndrome among others.

There is also a notable association between cerebral vasculitis and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. The amyloid deposition has been identified as a possible trigger for cerebral vasculitis in animal models 3.

Specific activation of the immune system and more specifically, T cells by various triggers are thought to cause the inflammation of blood vessels in the central nervous system leading to cerebral vasculitis. Immunohistochemical staining of biopsy samples in cerebral vasculitis showed an extensive infiltration around the small cerebral arteries by CD45R0+ T cells. Matrix metalloproteinases such as MMP-9 have been described as one of the prime effector molecules in animal models of cerebral vasculitis.

Histopathology in cerebral vasculitis shows small and medium vessel vasculitis affecting parenchymal and leptomeningeal arteries. Three different types of vasculitic patterns have been described in cerebral vasculitis. These include granulomatous type, necrotizing type, and lymphocytic type. The most common type, granulomatous, shows numerous granulomas with multinucleated cells. The necrotizing type presents with fibrinoid necrosis similar, and lymphocytic type shows extensive lymphocytic inflammation with plasma cells.

Cerebral vasculitis symptoms

The onset of cerebral vasculitis is usually insidious, and the course is slowly progressive. Acute presentations have also been reported but are, however, less common. Symptoms of cerebral vasculitis are non-specific, and multiple symptoms are usually present at the initial presentation. A headache is the most common presenting symptom; other common presenting symptoms include cognitive dysfunction and stroke. Overall, the presenting symptoms and signs from the most common to the least common include:

- Severe headaches that don’t go away

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Stroke

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Aphasia

- Visual symptoms including visual field deficits, blurred vision, and double vision

- Seizures or convulsions

- Ataxia (difficulty with coordination)

- Papilledema

- Intracranial bleeding

- Amnestic syndrome (forgetfulness or confusion)

- Swelling of the brain (encephalopathy)

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Abnormal sensations or loss of sensations

- Vision problems

A combination of symptoms is usually present in most patients. cerebral vasculitis should always be considered as a possibility in cases of rapidly progressive cognitive decline and personality changes of unknown etiology.

Cerebral vasculitis diagnosis

Diagnosing cerebral vasculitis poses a challenge for physicians. Many of the key symptoms of cerebral vasculitis are shared by other diseases and infections, so these “mimics” must be ruled out. There is no single diagnostic test for cerebral vasculitis, so your doctor will consider a number of factors, including a detailed medical history, a physical examination, laboratory tests, and specialized imaging studies. A biopsy of tissue from blood vessels in the brain or spine is usually required to confirm a diagnosis.

Laboratory investigations like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA) are neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis. The only useful laboratory investigation is cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination which shows an abnormality in more than 90% of the cases. A mild increase in the leukocyte count or total protein or both is seen in a majority of cases.

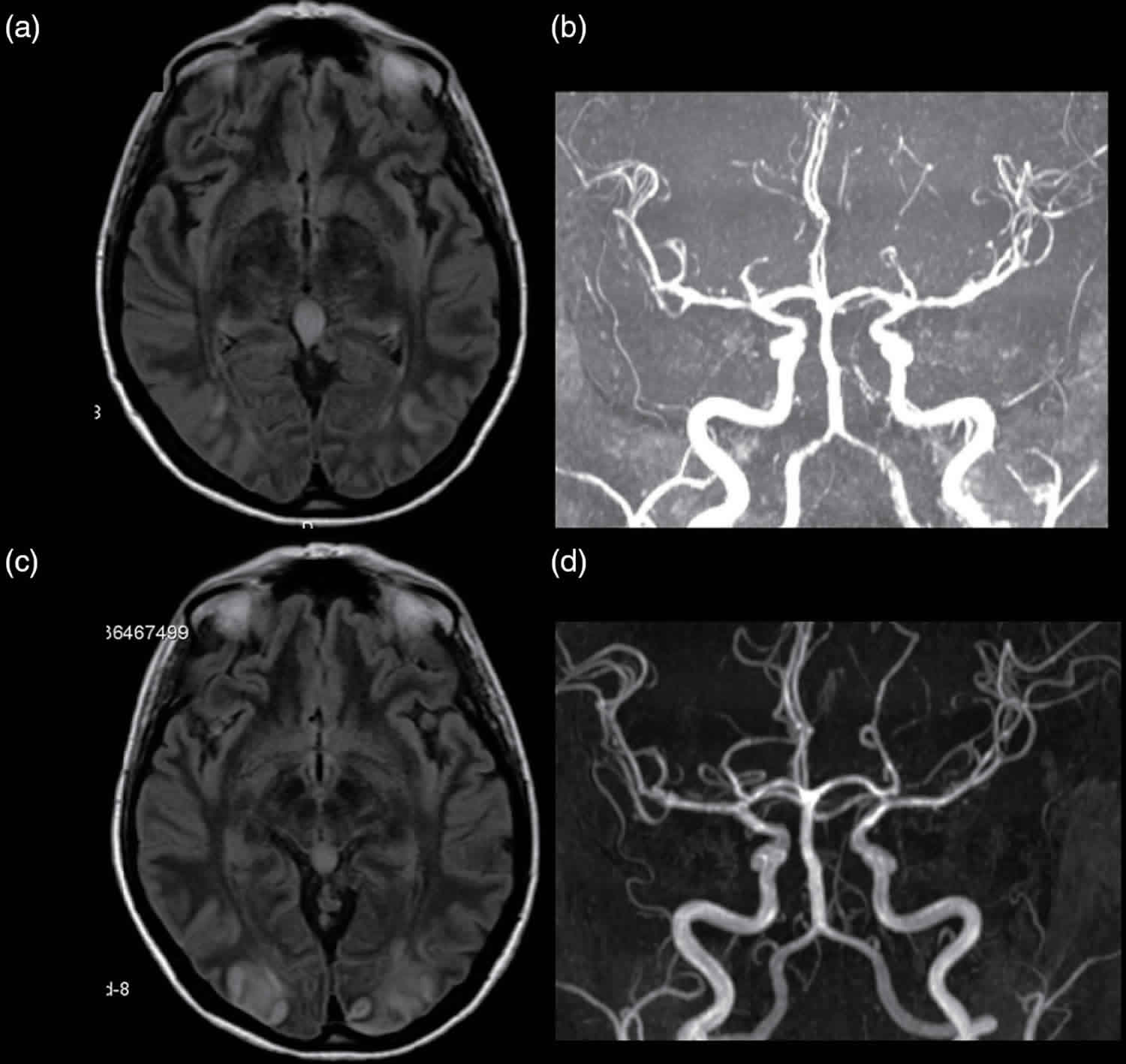

Radiographic findings are quite useful in cases of cerebral vasculitis, an abnormal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is seen in more than 90% of a case of cerebral vasculitis, with ischemia being the most common abnormality noted 4.

The diagnostic criteria for cerebral vasculitis formulated by Calabrese and Mallek are used for diagnosis, and a diagnosis is made if all of 3 diagnostic criteria are met. These include:

- the presence of an unexplained acquired neurologic deficit after extensive investigation for other causes,

- the presence of evidence of an inflammatory arteritic process within the central nervous system by either angiography or histopathological examination or both,

- no evidence of any other system vasculitis or any other disorders to which the angiographic or histopathologic features can be secondary.

Henceforth, the principal tools in the diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis are conventional angiography and central nervous system biopsy. Abnormal findings noted in angiography include alternating segments of stenosis and normal or dilated segments and arterial occlusions. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be used in the diagnosis instead of conventional angiography. However, it has a lesser sensitivity compared to a conventional angiogram. Central nervous system biopsy can also be used in the diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis, however, the sensitivity of biopsy is lower and the specificity higher.

A diagnostic approach which combines the clinical, laboratory and radiologic findings with angiography and, if a required biopsy is most prudent.

Cerebral vasculitis treatment

The treatment strategies for cerebral vasculitis are primarily derived from case reports and cohort studies. In most patients use of high-dose corticosteroid, such as prednisone, to reduce inflammation, alone or in combination with cyclophosphamide was shown to improve symptoms. For more severe cases, prednisone is used in combination with drugs that suppress the immune system’s response, such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. The response rates for both monotherapy and combination therapy were found to be similar, around 80%. The general recommendation is to start oral prednisone therapy promptly at the time of diagnosis at an initial dose of 1 mg/kg per day. In nonresponsive cases, cyclophosphamide should be started promptly. The sufficient duration of therapy is 12 to 18 months in most patients. In patients with more severe presentations, 1 gm methylprednisone per day for three days along with cyclophosphamide can be used. However, the evidence of intravenous (IV) steroids being superior to oral regimen has not been noted. Pulses of IV methylprednisone can be given as required for disease flares 5.

In cases of cerebral vasculitis resistant to both corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockers (infliximab, etanercept) and mycophenolate mofetil can be used to treat the disease. These should be used as adjunctive therapy along with the standard therapy. Prophylactic therapy against Pneumocystis jirovecii and osteoporosis should be given to all patients along with the standard therapy.

In addition to medication, other forms of treatment may include physical, occupational or speech therapy. If memory is affected, brain activities that enhance memory may be recommended.

Serial MRI and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) every 4 to 6 weeks after initiation of the treatment and then every 3 to 4 months during the first year along with thorough neurological examinations are indicated for monitoring the course of the illness.

Side effects

The medications used to treat cerebral vasculitis have potentially serious side effects, such as lowering your body’s ability to fight infection, and potential bone loss (osteoporosis), among others. Therefore, it’s important to see your doctor for regular checkups. Medications may be prescribed to offset side effects. Infection prevention is also important. Talk to your doctor about getting a flu shot, pneumonia vaccination, and/or shingles vaccination, which can reduce your risk of infection.

Cerebral vasculitis prognosis

Even with effective treatment, relapses are common for individuals with cerebral vasculitis. If your initial symptoms return or you develop new ones, report them to your doctor as soon as possible. Regular check-ups and ongoing monitoring of lab and imaging tests are important in detecting relapses early.

Prognostic indicators from randomized control trials lack cases of cerebral vasculitis. However, data obtained from retrospective observational studies show favorable outcomes when patients are treated with either corticosteroids or a combination of corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. Some degree of reduction in life expectancy is observed in cerebral vasculitis cases when compared to general population. Poor outcomes are found to be associated with larger vessel involvement.

References- Godasi R, Bollu PC. Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis. [Updated 2019 May 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482476

- Younger DS, Coyle PK. Central Nervous System Vasculitis due to Infection. Neurol Clin. 2019 May;37(2):441-463.

- de Boysson H, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis Nodosa Neurologic Manifestations. Neurol Clin. 2019 May;37(2):345-357.

- Caputi L, Erbetta A, Marucci G, Pareyson D, Eoli M, Servida M, Parati E, Salsano E. Biopsy-proven primary angiitis of the central nervous system mimicking leukodystrophy: A case report and review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2019 Jun;64:42-44.

- Maggi P, Absinta M, Grammatico M, Vuolo L, Emmi G, Carlucci G, Spagni G, Barilaro A, Repice AM, Emmi L, Prisco D, Martinelli V, Scotti R, Sadeghi N, Perrotta G, Sati P, Dachy B, Reich DS, Filippi M, Massacesi L. Central vein sign differentiates Multiple Sclerosis from central nervous system inflammatory vasculopathies. Ann. Neurol. 2018 Feb;83(2):283-294.