What is cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

The cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) are abnormal cells are found on the surface of the cervix. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is not cancer. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia are changes to the cells that cover the outside of the cervix (squamous cells).

It is widely accepted that invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, which is the commonest histological type, is preceded by a pre-invasive stage of the disease, where the abnormal cells are confined to the epithelium. This stage of non-invasive disease is known as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and is directly related to the processes of infection and integration of human papillomavirus (HPV) as described in the previous chapter.

There are 3 grades of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and they relate to how deeply the abnormal cells have gone into the skin covering the cervix.

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 (CIN 1) or low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) – up to one third of the thickness of the lining covering the cervix has abnormal cells.

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) – between one third and two thirds of the skin covering the cervix has abnormal cells. CIN2 is defined by nuclear pleomorphism with mitotic activity extending to the upper two-thirds of the epithelium. There is usually little or no koilocytosis.

- Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) or carcinoma in situ (CIS) – the full thickness of the lining covering the cervix has abnormal cells

The development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) involves a progression from early changes (CIN 1) involving the deeper layers of the epithelium to full thickness involvement at its most severe (CIN 3) equating to carcinoma in situ (CIS) (Figure 1).

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 to 3 (CIN 1 to CIN 3) have increasing risk of progression to invasion and decreasing likelihood of natural regression.

Both the cell abnormality (mild, moderate or severe) and the CIN level are taken into account when deciding which treatment will be best for you. The treatment aims to remove or destroy the abnormal cervical cells.

Figure 1. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades

Footnote: CIN = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; CIS = carcinoma in situ, may also be called CIN 3

Footnote: CIN = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; CIS = carcinoma in situ, may also be called CIN 3Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) usually represents reversible infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) doesn’t normally need treatment as the cell changes often return to normal over time (usually resolves spontaneously within 9-12 months). There are numerous follow-up studies of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) showing a highly variable risk of progression to CIN 2-3 and a consequent risk of invasive cancer in a small minority of patients 1.

A large retrospective follow-up study of mild, moderate and severe dysplasia by Holowaty et al. 2 showed that the majority of cases of mild (62.2%) and moderate dysplasia (53.7%) regressed (two negative smears within 2 years) while progression to moderate dysplasia or worse was approximately 25% within 5 years, which is consistent with other studies.

Likelihood of progression depends on persistence of HPV, its integration into the host genome and its type 3:

- HPV16 and 33 have the highest risk of progression to CIN3.

- HPV16 and 31 to have the least likelihood of regression.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) is an intermediate lesion and there is evidence from the ALTS trial that around 40% resolves spontaneously but was less likely to do so when HPV16-related 4. The retrospective study by Holowaty et al. 2 showed that the majority of moderate dysplasia regressed dysplasia regressed (53.7%) while progression was more likely than for mild dysplasia.

The cumulative actuarial rate of progression at 5 years per 100 women of moderate dysplasia to invasive cancer was intermediate between mild (0.4) and severe dysplasia (3.9) 2.

In view of its intermediate position between CIN1 and CIN3 in terms of risk of progression and the clinical importance of deciding whether CIN2 should be managed as a high-grade precancerous lesion, immunohistochemistry using the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4A is now recommended in the US to improve consistency of diagnosis and define high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 5.

P16INK4A staining helps distinguish CIN2 from:

- CIN1 in immature metaplasia

- Non-neoplastic mimics such as immature squamous metaplasia, atrophic metaplasia and repair

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) is defined by nuclear pleomorphism involving the full thickness of the squamous epithelium with mitotic activity at all levels. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) (and severe dysplasia) equates to carcinoma in situ (CIS), which term is seldom used nowadays.

Risk of progression is highest for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) and inter-observer variation is considerably less than for CIN1 or CIN2 6. Microinvasive carcinoma is almost always seen in a background of widespread CIN3 further demonstrating its malignant potential. The exact risk is difficult to calculate because most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3)/carcinoma in situ is treated when diagnosed.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia symptoms

Women with early cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia usually have no symptoms. Symptoms often do not begin until the cervical cancer becomes invasive and grows into nearby tissue. When this happens, the most common symptoms are:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as bleeding after vaginal sex, bleeding after menopause, bleeding and spotting between periods, and having (menstrual) periods that are longer or heavier than usual. Bleeding after douching or after a pelvic exam may also occur.

- An unusual discharge from the vagina − the discharge may contain some blood and may occur between your periods or after menopause.

- Pain during sex.

These signs and symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than cervical cancer. For example, an infection can cause pain or bleeding. Still, if you have any of these symptoms, see a health care professional right away. Ignoring symptoms may allow the cancer to grow to a more advanced stage and lower your chance for effective treatment.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women follow these guidelines to help find cervical cancer early. Following these guidelines can also find pre-cancers, which can be treated to keep cervical cancer from forming.

- All women should begin cervical cancer testing (screening) at age 21. Women aged 21 to 29, should have a Pap test every 3 years. HPV testing should not be used for screening in this age group (it may be used as a part of follow-up for an abnormal Pap test).

- Beginning at age 30, the preferred way to screen is with a Pap test combined with an HPV test every 5 years. This is called co-testing and should continue until age 65.

- Another reasonable option for women 30 to 65 is to get tested every 3 years with just the Pap test.

- Women who are at high risk of cervical cancer because of a suppressed immune system (for example from HIV infection, organ transplant, or long-term steroid use) or because they were exposed to DES in utero may need to be screened more often. They should follow the recommendations of their health care team.

- Women over 65 years of age who have had regular screening in the previous 10 years should stop cervical cancer screening as long as they haven’t had any serious pre-cancers (like CIN2 or CIN3) found in the last 20 years. Women with a history of CIN2 or CIN3 should continue to have testing for at least 20 years after the abnormality was found.

- Women who have had a total hysterectomy (removal of the uterus and cervix) should stop screening (such as Pap tests and HPV tests), unless the hysterectomy was done as a treatment for cervical pre-cancer (or cancer). Women who have had a hysterectomy without removal of the cervix (called a supra-cervical hysterectomy) should continue cervical cancer screening according to the guidelines above.

- Women of any age should NOT be screened every year by any screening method.

- Women who have been vaccinated against HPV should still follow these guidelines.

Some women believe that they can stop cervical cancer screening once they have stopped having children. This is not true. They should continue to follow American Cancer Society guidelines.

Although annual (every year) screening should not be done, women who have abnormal screening results may need to have a follow-up Pap test (sometimes with a HPV test) done in 6 months or a year.

The American Cancer Society guidelines for early detection of cervical cancer do not apply to women who have been diagnosed with cervical cancer, cervical pre-cancer, or HIV infection. These women should have follow-up testing and cervical cancer screening as recommended by their health care team.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia treatment

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) usually represents reversible infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) doesn’t normally need treatment as the cell changes often return to normal over time (usually resolves spontaneously within 9-12 months). There are numerous follow-up studies of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) showing a highly variable risk of progression to CIN 2-3 and a consequent risk of invasive cancer in a small minority of patients 1.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) are managed as ‘high-grade’ cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and usually treated by excision or ablation when diagnosed at colposcopy.

There are a few different treatments that can remove the area of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. The advantage of these treatments is that the piece of cervical tissue that the colposcopist removes can be sent for examination under a microscope.

In the laboratory, the pathologist rechecks the level of cell changes in the piece of tissue to make sure your screening result was accurate. They also closely examine the whole piece of tissue to make sure that the area containing the abnormal cells has been completely removed.

Treatments include

Treatment aims to destroy or remove areas of the cervix identified as pre-cancer. Treatment methods may be ablative (destroying abnormal tissues by burning or freezing) or excisional (surgically removing abnormal tissues). With ablative methods, no tissue specimen is obtained for further confirmatory histopathological examination.

Each treatment method has eligibility criteria that should be met before proceeding with treatment. In this section, we will discuss use of cryotherapy, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) and cold knife conization (CKC). Other forms of therapy do exist, such as laser excision or ablation.

Hysterectomy is rarely an appropriate means to treat cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Unless there are other compelling reasons to remove the uterus, hysterectomy should not be performed for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

If a patient has a cervical abnormality that looks suspicious for cancer, the patient should NOT be treated with cryotherapy, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or cold knife conization (CKC). The appropriate next step for her is a cervical biopsy to confirm or rule out a diagnosis of cancer.

The choice of treatment will depend on:

- the benefits and harms of each method

- the location, extent and severity of the lesion

- the cost and resources required to provide treatment

- the training and experience of the provider.

Table 1. Comparison of the characteristics of treatment methods for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

| Method | Procedure | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryotherapy | A highly cooled metal disc is applied to the cervix for the purpose of freezing and therefore destroying precancerous lesions, with subsequent regeneration to normal epithelium. |

|

|

| Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) | Abnormal areas are removed from the cervix using a loop made of thin wire powered by an electrosurgical unit. |

|

|

| Cold knife conization (CKC) | A cone-shaped area is removed from the cervix, including portions of the outer and inner cervix. |

|

|

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy eliminates precancerous areas on the cervix by freezing (an ablative method) 7. It involves applying a highly cooled metal disc (cryoprobe) to the cervix and freezing the abnormal areas (along with normal areas) covered by it (see Figure 2). The supercooling of the cryoprobe is accomplished using a tank with compressed carbon dioxide (CO2) or nitrous oxide (N2O) gas. Cryotherapy can be performed at all levels of the health system, by health-care providers (doctors, nurses and midwives) who are skilled in pelvic examination and trained in cryotherapy. It takes about 15 minutes and is generally well tolerated and associated with only mild discomfort. It can, therefore, be performed without anaesthesia. Following cryotherapy, the frozen area regenerates to normal epithelium.

Eligibility criteria: Screen-positive women or women with histologically confirmed CIN2+ are eligible for cryotherapy if the entire lesion and squamocolumnar junction are visible, and the lesion does not cover more than three quarters of the ectocervix. If the lesion extends beyond the cryoprobe being used, or into the endocervical canal, the patient is not eligible for cryotherapy. The patient is not eligible for cryotherapy if the lesion is suspicious for invasive cancer.

Post procedure: It takes a month for the cervical tissue to regenerate. The patient should be advised that during this time she may have a profuse, watery discharge and she should avoid sexual intercourse until all discharge stops, or use a condom if intercourse cannot be avoided.

Figure 2. Cryotherapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure

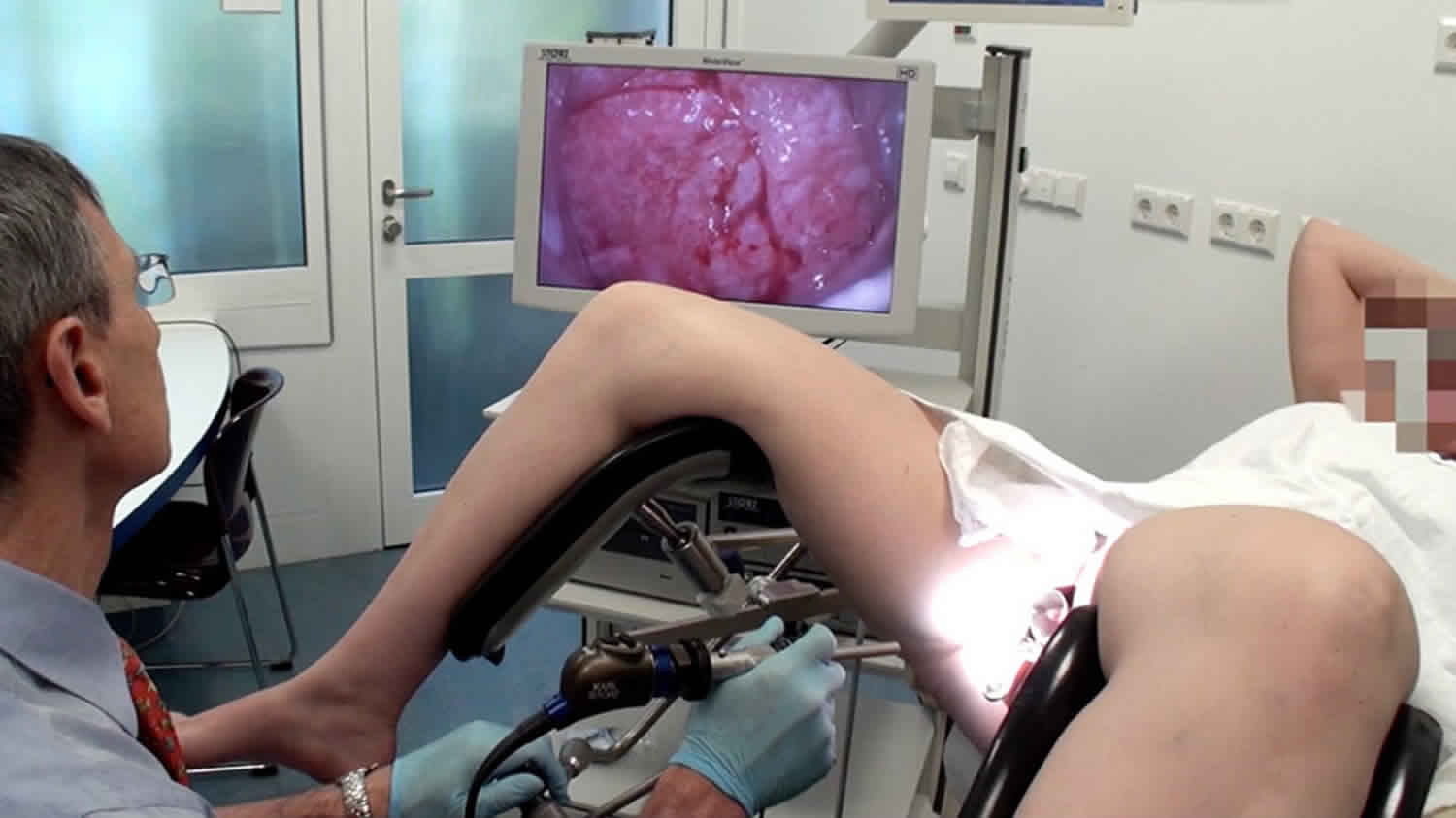

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is also called large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) or loop diathermy, is the removal of abnormal areas from the cervix using a loop made of thin wire powered by an electrosurgical unit. The loop tool cuts and coagulates at the same time, and this is followed by use of a ball electrode to complete the coagulation (see Figure 3). Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is the most common treatment for abnormal cervical cells. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) aims to remove the lesion and the entire transformation zone. The tissue removed can be sent for examination to the histopathology laboratory, allowing the extent of the lesion to be assessed. Thus, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) serves a double purpose: it removes the lesion (thus treating the pre-cancer) and it also produces a specimen for pathological examination. The procedure can be performed under local anaesthesia on an outpatient basis and usually takes less than 30 minutes. However, following loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), a patient should stay at the outpatient facility for a few hours to assure bleeding does not occur.

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is a relatively simple surgical procedure, but it should only be performed by a trained health-care provider with demonstrated competence in the procedure and in recognizing and managing intraoperative and postoperative complications, such as haemorrhage; e.g. a gynaecologist. LEEP is best carried out in facilities where back-up is available for management of potential problems; in most cases, this will limit LEEP to at least the secondary-level facilities (i.e. district hospitals).

Eligibility criteria: Screen-positive women or women with histologically confirmed CIN2+ are eligible for LEEP if the lesion is not suspicious for invasive cancer.

Post procedure: The patient should be advised to expect mild cramping for a few days and some vaginal discharge for up to one month. Initially, this can be bloody discharge for 7–10 days, and then it can transition to yellowish discharge. It takes one month for the tissue to regenerate, and during this time the patient should avoid sexual intercourse or use a condom if intercourse cannot be avoided.

Figure 3. LEEP cone biopsy

Cold knife conization

Cold knife conization is the removal of a cone-shaped area from the cervix, including portions of the outer (ectocervix) and inner cervix (endocervix) (see Figure 4). The amount of tissue removed will depend on the size of the lesion and the likelihood of finding invasive cancer. The tissue removed is sent to the pathology laboratory for histopathological diagnosis and to ensure that the abnormal tissue has been completely removed. A cold knife conization is usually done in a hospital, with the necessary infrastructure, equipment, supplies and trained providers. It should be performed only by health-care providers with surgical skill – such as gynaecologists or surgeons trained to perform the procedure – and competence in recognizing and managing complications, such as bleeding. The procedure takes less than one hour and is performed under general or regional (spinal or epidural) anesthesia. The patient may be discharged from hospital the same or the next day.

Eligibility criteria: Cold knife conization should be reserved for cases that cannot be resolved with cryotherapy or LEEP. It should be considered in the presence of glandular pre-cancer or microinvasive cancer lesions of the cervix.

Post procedure: Following cold knife conization, patients may have mild cramping for a few days and a bloody vaginal discharge, transitioning into a yellow discharge for 7–14 days. It takes 4–6 weeks for the cervix to heal (depending on the extent of the procedure) and during this time the patient should avoid sexual intercourse or use a condom if intercourse cannot be avoided.

Figure 4. Cold knife conization

Treatment Possible complications

All three treatment modalities may have similar complications in the days following the procedure. All of these complications may be indications of continuing bleeding from the cervix or vagina or an infection that needs to be treated.

Patients should be advised that if they have any of the following symptoms after cryotherapy, LEEP or cold knife conization, they should seek care at the closest facility without delay:

- bleeding (more than menstrual flow)

- abdominal pain

- foul-smelling discharge

- fever.

Follow-up after treatment

A follow-up visit including cervical cancer screening is recommended 12 months after treatment to evaluate the woman post-treatment and detect recurrence. If this follow-up rescreen is negative, the woman can be referred back to the routine screening programme.

An exception is if the patient has a histopathological result at the time of treatment that indicates CIN3 or adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) based on a specimen from LEEP or cold knife conization. In this case, rescreening is recommended every year for three years. If these rescreens are negative, she is then referred back to the routine screening programme.

If the patient treated for pre-cancer has a positive screen on her follow-up visit (indicating persistence or recurrence of cervical pre-cancer), retreatment is needed. If the initial treatment was with cryotherapy, then retreatment should be performed using LEEP or cold knife conization, if feasible.

If a histopathological result from a specimen obtained from a punch biopsy, LEEP or cold knife conization procedure indicates cancer, it is critical that the patient be contacted and advised that she must be seen at a tertiary care hospital as soon as possible.

References- Bansal N, Wright JD, Cohen CJ, Herzog TJ (2008). Natural history of established low-grade cervical intraepithelial (CIN1) lesions. Anticancer Res 28:1763-6.

- Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, To T (1999). Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:252-8.

- Jaisamrarn U, Castellsague X, Garland SM et al. (2013). Natural history of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLoS One 8:e79260.

- Castle PE, Schiffman M, Wheeler CM, Solomon D (2009). Evidence for frequent regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-grade 2. Obstet Gynecol 113:18-25.

- Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT et al. (2012). The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arc Pathol Lab Med 136:1266-97.

- Stoler MH, Schiffman M (2001). Interobserver reproducibility of cervical cytologic and histologic interpretations: realistic estimates from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. JAMA 285:1500-5.

- Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. 5, Screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269601