Cervical strain

Cervical strain or cervical neck strain may result from abnormalities in the soft tissues—the muscles, ligaments, and nerves—as well as in bones and the discs between the bones. The most common causes of cervical strain are soft-tissue abnormalities due to injury (a sprain) or prolonged wear and tear. In rare instances, infection or tumors may cause neck pain. In some people, neck problems may be the source of pain in the upper back, shoulders, or arms.

When your neck is sore, you may have difficulty moving it, such as turning to one side. Many people describe this as having a stiff neck.

It is common for neck pain to get worse for a day or two after an injury, but it should start to feel better after that. You may have more pain and stiffness for several days before it gets better. This is expected. It may take a few weeks or longer for it to heal completely. Good home treatment can help you get better faster and avoid future neck problems.

If neck pain involves compression of your nerves, you may feel numbness, tingling, or weakness in your arm or hand.

If severe neck pain occurs following an injury (motor vehicle accident, diving accident, or fall), a trained professional, such as a paramedic, should immobilize the patient to avoid the risk of further injury and possible paralysis. Medical care should be sought immediately.

Immediate medical care should also be sought when an injury causes pain in the neck that radiates down the arms and legs.

Radiating pain or numbness in your arms or legs causing weakness in the arms or legs without significant neck pain should also be evaluated.

If there has not been an injury, you should seek medical help right away if you have:

- A fever and headache, and your neck is so stiff that you cannot touch your chin to your chest. This may be meningitis. Call your local emergency number or get to a hospital.

- Symptoms of a heart attack, such as shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, vomiting, or arm or jaw pain.

- Neck pain that is:

- Continuous and persistent

- Severe

- Accompanied by pain that radiates down the arms or legs

- Accompanied by headaches, numbness, tingling, or weakness

See your doctor if:

- Symptoms do not go away in 1 week with self-care

- You have numbness, tingling, or weakness in your arm or hand

- Your neck pain was caused by a fall, blow, or injury — if you cannot move your arm or hand, have someone call your local emergency services number

- You have swollen glands or a lump in your neck

- Your pain does not go away with regular doses of over-the-counter pain medicine

- You have difficulty swallowing or breathing along with the neck pain

- The pain gets worse when you lie down or wakes you up at night

- Your pain is so severe that you cannot get comfortable

- You lose control over urination or bowel movements

- You have trouble walking and balancing

Cervical spine anatomy

Your spine is made up of 24 bones, called vertebrae, that are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Other parts of your spine include:

- Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae (foramen).

- Intervertrebral disks. In between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. They act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

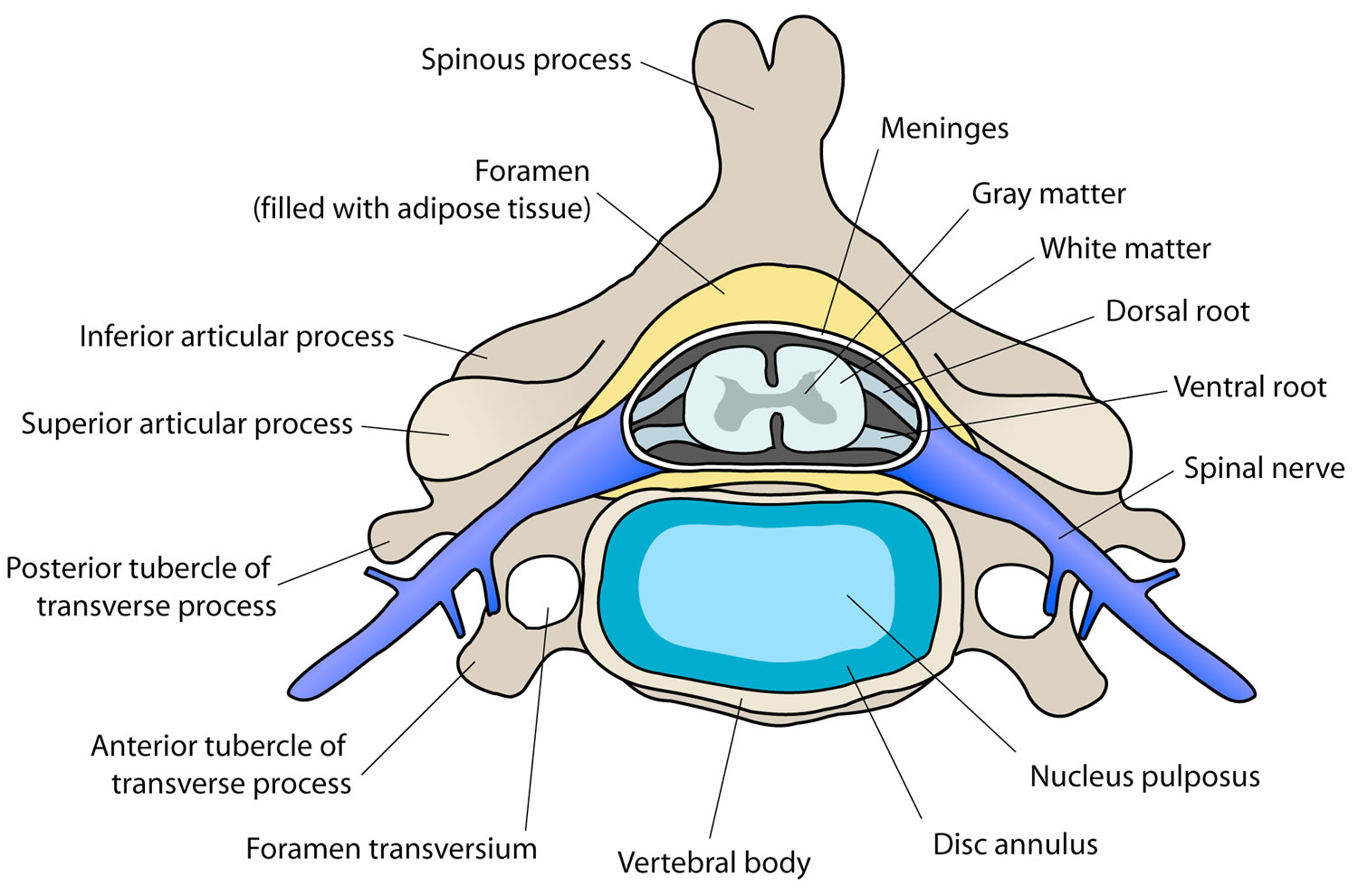

Intervertebral disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. They are made up of two components:

- Annulus fibrosus. This is the tough, flexible outer ring of the disk.

- Nucleus pulposus. This is the soft, jelly-like center of the disk.

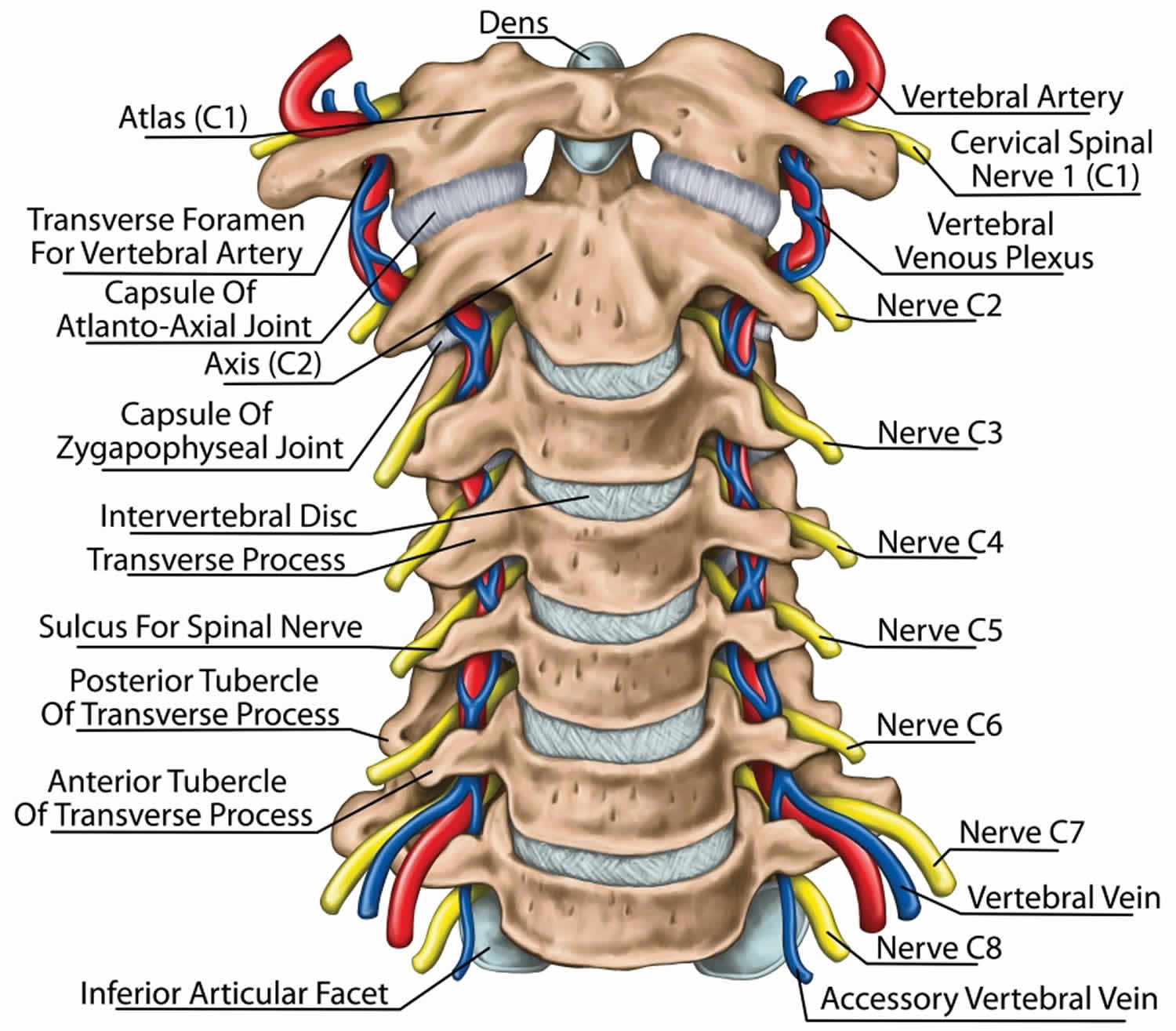

The cervical spine is made up of the first 7 vertebrae and functions to provide mobility and stability to the head, while connecting it to the relative immobile thoracic spine (see the image below). The first 2 vertebral bodies are quite different from the rest of the cervical spine. The atlas, or C1, articulates superiorly with the occiput and inferiorly with the axis, or C2.

The atlas is ring-shaped and does not have a body, unlike the rest of the vertebrae. The body has become part of C2, and it is called the odontoid process, or dens. The atlas is made up of an anterior arch, a posterior arch, 2 lateral masses, and 2 transverse processes. The transverse foramen, through which the vertebral artery passes, is enclosed by the transverse process. On each lateral mass is a superior and inferior facet (zygapophyseal) joint. The superior articular facets are kidney-shaped, concave, and face upward and inward. These superior facets articulate with the occipital condyles, which face downward and outward. The relatively flat inferior articular facets face downward and inward to articulate with the superior facets of the axis.

The axis has a large vertebral body, which contains the fused remnant of the C1 body, the dens. The dens articulates with the anterior arch of the atlas via its anterior articular facet and is held in place by the transverse ligament. The axis is composed of a vertebral body, heavy pedicles, laminae, and transverse processes, which serve as attachment points for muscles. The axis articulates with the atlas by its superior articular facets, which are convex and face upward and outward.

The remaining cervical vertebrae, C3-C7, are similar to each other, but they are very different from C1 and C2. They each have a vertebral body, which is concave on its superior surface and convex on its inferior surface. On the superior surfaces of the bodies are raised processes or hooks called uncinate processes, which articulate with depressed areas on the inferior aspect of the superior vertebral bodies called the echancrure or anvil. These uncovertebral joints are most noticeable near the pedicles and are usually referred to as the joints of Luschka 1. These joints are believed to be the result of degenerative changes in the annulus, which leads to fissuring in the annulus and the creation of the joint. The spinous processes of C3-C5 are usually bifid, in comparison to the spinous processes of C6 and C7, which are usually tapered.

The facet joints in the cervical spine are diarthrodial synovial joints with fibrous capsules. The joint capsules in the lower cervical spine are more lax compared with other areas of the spine to allow for gliding movements of the facets. The joints are inclined at 45° from the horizontal plane and angled 85° from the sagittal plane. This alignment helps to prevent excessive anterior translation and is important in weight bearing 2.

The fibrous capsules are innervated by mechanoreceptors (types I, II, and III), and free nerve endings have been found in the subsynovial loose areolar and dense capsular tissues 3. In fact, there are more mechanoreceptors in the cervical spine than in the lumbar spine 4. This neural input from the facets may be important for proprioception and pain sensation and may modulate protective muscular reflexes that are important in preventing joint instability and degeneration.

The facet joints in the cervical spine are innervated by both the anterior and dorsal rami. The occipitoatlantal joint and atlantoaxial joint are innervated by the ventral rami of the first and second cervical spinal nerves. Two branches of the dorsal ramus of the third cervical spinal nerve innervate the C2-C3 facet joint, a communicating branch and a medial branch known as the third occipital nerve.

The remaining cervical facets, C3-C4 to C7-T1, are supplied by the dorsal rami medial branches that arise one level cephalad and caudad to the joint 5. Therefore, each joint from C3-C4 to C7-T1 is innervated by the medial branches above and below. These medial branches send off articular branches to the facet joints as they wrap around the waists of the articular pillars.

Intervertebral discs are located between each vertebral body caudad to the axis. The discs are composed of 4 parts, including the nucleus pulposus in the middle, the annulus fibrosis surrounding the nucleus, and 2 end plates that are attached to the adjacent vertebral bodies. The discs are involved in cervical spine motion, stability, and weight bearing. The annular fibers are composed of collagenous sheets called lamellae, which are oriented 65-70° from the vertical and alternate in direction with each successive sheet. Therefore, the annular fibers are prone to injury with rotation forces because only one half of the lamellae are oriented to withstand the force in this direction 4. The middle and outer one third of the annulus is innervated by nociceptors, and phospholipase A2 has been found in the disc and may be an inflammatory mediator 6.

Several ligaments of the cervical spine, which provide stability and proprioceptive feedback, are worth mentioning 7. The transverse ligament, the major portion of the cruciate ligament, arises from tubercles on the atlas and stretches across its anterior ring while holding the dens against the anterior arch. A synovial cavity is located between the dens and the transverse process. This ligament allows for rotation of the atlas on the dens and is responsible for stabilizing the cervical spine during flexion, extension, and lateral bending. The transverse ligament is the most important ligament in preventing abnormal anterior translation 8.

The alar ligaments run from the lateral aspects of the dens to the ipsilateral medial occipital condyles and to the ipsilateral atlas. The alar ligaments limit axial rotation and side bending. If the alar ligaments are damaged, as in a whiplash injury, the joint complex becomes hypermobile, which can lead to kinking of the vertebral arteries and stimulation of the nociceptors and mechanoreceptors. This may be associated with the typical complaints of patients with whiplash injuries such as headache, neck pain, and dizziness. The alar ligaments prevent excessive lateral and rotational motions, while allowing flexion and extension.

The anterior longitudinal ligament and the posterior longitudinal ligament are the major stabilizers of the intervertebral joints. Both ligaments are found throughout the entire length of the spine; however, the anterior longitudinal ligament is closely adhered to the discs in comparison to the posterior longitudinal ligament, and it is not well developed in the cervical spine. The anterior longitudinal ligament becomes the anterior atlantooccipital membrane at the level of the atlas, whereas the posterior longitudinal ligament merges with the tectorial membrane. Both ligaments continue onto the occiput. The posterior longitudinal ligament prevents excessive flexion and distraction 9.

The supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, and ligamentum flavum maintain stability between the vertebral arches. The supraspinous ligament runs along the tips of the spinous processes, the interspinous ligament runs between the spinous processes, and the ligamentum flavum runs from the anterior surface of the cephalad vertebra to the posterior surface of the caudad vertebra. The interspinous ligament and especially the ligamentum flavum control for excessive flexion and anterior translation 9. The ligamentum flavum also connects to and reinforces the facet joint capsules on the ventral aspect. The ligamentum nuchae is the cephalad continuation of the supraspinous ligament and has a prominent role in stabilizing the cervical spine.

Figure 1. Cervical spine

Figure 2. Cervical disc

Cervical strain causes

A common cause of cervical strain is muscle strain or tension. Most often, everyday activities are to blame. Such activities include:

- Bending over a desk for hours

- Having poor posture while watching TV or reading

- Having your computer monitor positioned too high or too low

- Sleeping in an uncomfortable position

- Sleeping on your abdomen or with too many or too few pillows

- Twisting and turning your neck in a jarring manner while exercising

- Cradling your phone between your shoulder and neck

- Emotional stress

- Tension headache

- Lifting things too quickly or with poor posture

- Carrying a heavy backpack or purse on one shoulder

- Whiplash

Accidents or falls can cause severe neck injuries, such as vertebral fractures, whiplash, blood vessel injury, and even paralysis.

Other causes include:

- Medical conditions, such as fibromyalgia

- Cervical arthritis or cervical spondylosis

- Ruptured disk

- Herniated disk

- Small fractures to the spine from osteoporosis

- Spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal)

- Sprains

- Muscle strain

- Infection of the spine (osteomyelitis, discitis, abscess)

- Meningitis

- Torticollis

- Cancer that involves the spine

- Cervical dystonia (spasmodic torticollis)

- Osteoarthritis (disease causing the breakdown of joints)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (inflammatory joint disease)

- Spinal stenosis

- Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders

- Trauma from accidents or falls

Injury

Because your neck is so flexible and because it supports your head, it is extremely vulnerable to injury. Motor vehicle or diving accidents, contact sports, and falls may result in neck injury. The regular use of safety belts in motor vehicles can help to prevent or minimize neck injury. A “rear end” automobile collision may result in hyperextension, a backward motion of the neck beyond normal limits, or hyperflexion, a forward motion of the neck beyond normal limits. The most common neck injuries involve the soft tissues: the muscles and ligaments. Severe neck injuries with a fracture or dislocation of the neck may damage the spinal cord and cause paralysis.

Cervical disc degeneration (spondylosis)

The disk acts as a shock absorber between the bones in the neck. In cervical disk degeneration (which typically occurs in people age 40 years and older), the normal gelatin-like center of the disk degenerates and the space between the vertebrae narrows. As the disk space narrows, added stress is applied to the joints of the spine causing further wear and degenerative disease. The cervical disk may also protrude and put pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots when the rim of the disk weakens. This is known as a herniated cervical disk.

Table 1. Neck pain red flags

| Red flag | Potential pathological process |

|---|---|

| Significant trauma (eg. fall in osteoporotic patient, motor vehicle accident) | Bony/ligamentous disruption of the cervical spine |

| History of rheumatoid arthritis | Atlanto-axial disruption |

| Infective symptoms (eg. fever, meningism, history of immunosuppression or intravenous drug use) | Infection

|

| Constitutional symptoms (eg. fevers, weight loss, anorexia, past or current history of malignancy) | Malignancy/infiltrative process Rheumatological disease

|

| Neurology (eg. signs or symptoms of upper motor neuron pathology) | Cervical cord compression Demyelinating process |

| Ripping/tearing neck sensation | Arterial dissection (carotid/vertebral) |

| Concurrent chest pain, shortness of breath, diaphoresis (excessive sweating) | Myocardial ischemia (heart attack) |

Cervical sprain symptoms

The symptoms you experience will depend on what’s causing your neck pain but may include:

- pain in the neck, shoulders and/or upper chest

- stiff neck

- difficulty turning your head

In most cases neck pain will go away in a few days. If it doesn’t get better, or you develop other symptoms, you should see your doctor.

Symptoms of whiplash

An injury to the neck due to a motor vehicle crash is often referred to as a whiplash injury. Typically, this occurs as a result of a rear-end collision and any structure of the neck might be strained.

Common symptoms of a whiplash injury include neck pain, headache and neck stiffness. Some people may also feel unsteady or light headed. Recovery from whiplash depends on the individual and the extent of the injury, but can vary from a few weeks to months.

Symptoms of neck pain

Symptoms of neck pain and the sensations you feel can help your doctor to diagnose the cause. Here are some symptoms.

Muscle spasm

A spasm is a sudden, powerful, involuntary contraction of muscles. The muscles feel painful, stiff and knotted. If you have neck muscle spasms, you may not be able to move your neck — sometimes people call it a crick in the neck. Your doctor or physiotherapist may call it acute torticollis or wry neck.

Muscle ache

The neck muscles are sore and may have hard knots (trigger points) that are tender to touch. Pain is often felt up the middle of the back of the neck, or it may ache on one side only.

Stiffness

The neck muscles are tight and if you spend too long in one position they feel even tighter. Neck stiffness can make it difficult or painful to move your neck.

Nerve pain

Pain from the neck can radiate down the arms, and sometimes, the legs. You may feel a sensation of pins and needles or tingling in your arms, which can be accompanied by numbness, burning or weakness.

Headaches

Headaches are common in conjunction with neck problems. They are usually a dull aching type of headache, rather than sharp pain. While the headaches are often felt at the back of the head, the pain may also radiate to the sides, and even the front of the head.

Reduced range of motion

If you can’t turn your head to the side to the same degree towards each shoulder, or you feel limited in how far forward you can lower your head to your chest, or how far you can tilt your head back, you may have reduced range of motion. Your doctor will be able to test this.

Cervical strain diagnosis

Your healthcare provider will perform a physical exam and ask about your neck pain, including how often it occurs and how much it hurts.

Your doctor will probably not order any tests during the first visit. Tests are only done if you have symptoms or a medical history that suggests a tumor, infection, fracture, or serious nerve disorder. In that case, the following tests may be done:

- X-rays of the neck

- CT scan of the neck or head

- Blood tests such as a complete blood count (CBC)

- MRI of the neck

If the pain is due to muscle spasm or a pinched nerve, your provider may prescribe a muscle relaxant or a more powerful pain reliever. Over-the-counter medicines often work as well as prescription drugs. At times, your provider may give you steroids to reduce swelling. If there is nerve damage, your provider may refer you to a neurologist, neurosurgeon, or orthopedic surgeon for consultation.

Cervical strain treatment

There is a paucity of evidence examining the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-specific neck pain treatment 10.

Apart from exercise and physiotherapy, there is little evidence to support other conservative measures. In several randomized controlled trials, acupuncture has been shown to be efficacious at treating chronic neck pain in the short term, with only limited evidence for long-term effects 11. A large study with 80% pain relief as the criterion end-point demonstrated that injection of a perpetrating facet joint relieved pain in 39% of cases30 and has been suggested to be part of a diagnostic algorithm for neck pain 12. However, there is a lack of supporting evidence for cervical intra-articular facet joint injections and cervical epidural injections are not without risk 13.

Home remedies

Treatment and self-care for your cervical neck strain depend on the cause of the pain. You will need to learn:

- How to relieve the pain

- What your activity level should be

- What medicines you can take

For minor, common causes of cervical neck strain:

- Take over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB) or acetaminophen (Tylenol).

- Apply heat or ice to the painful area. Use ice for the first 48 to 72 hours, and then use heat after that.

- Try using a heating pad on a low or medium setting for 15 to 20 minutes every 2 to 3 hours. Try a warm shower in place of one session with the heating pad. You can also buy single-use heat wraps that last up to 8 hours.

- You can also try an ice pack for 10 to 15 minutes every 2 to 3 hours.

- Apply heat with warm showers, hot compresses, or a heating pad. To prevent injury to your skin, DO NOT fall asleep with a heating pad or ice bag in place.

- Stop normal physical activity for the first few days. This helps calm your symptoms and reduce inflammation.

- Do slow range-of-motion exercises, up and down, side to side, and from ear to ear. This helps gently stretch the neck muscles.

- Have a partner gently massage the sore or painful areas. Gently rub the area to relieve pain and help with blood flow. Do not massage the area if it hurts to do so.

- Try sleeping on a firm mattress with a pillow that supports your neck. You may want to get a special neck pillow. Place it under your neck, not under your head. Placing a tightly rolled-up towel under your neck while you sleep will also work. If you use a neck pillow or rolled towel, do not use your regular pillow at the same time.

- Ask your health care provider about using a soft neck collar to relieve discomfort. However, using collar for a long time can weaken neck muscles. Take it off from time to time to allow the muscles to get stronger.

- If you were given a neck brace (cervical collar) to limit neck motion, wear it as instructed for as many days as your doctor tells you to. Do not wear it longer than you were told to. Wearing a brace for too long can make neck stiffness worse and weaken the neck muscles.

To prevent future neck pain, do exercises to stretch and strengthen your neck and back. Learn how to use good posture, safe lifting techniques, and proper body mechanics.

Neck strain or sprain rehab exercises

Here are some examples of exercises for you to try. The exercises may be suggested for a condition or for rehabilitation. Start each exercise slowly. Ease off the exercises if you start to have pain.

You will be told when to start these exercises and which ones will work best for you.

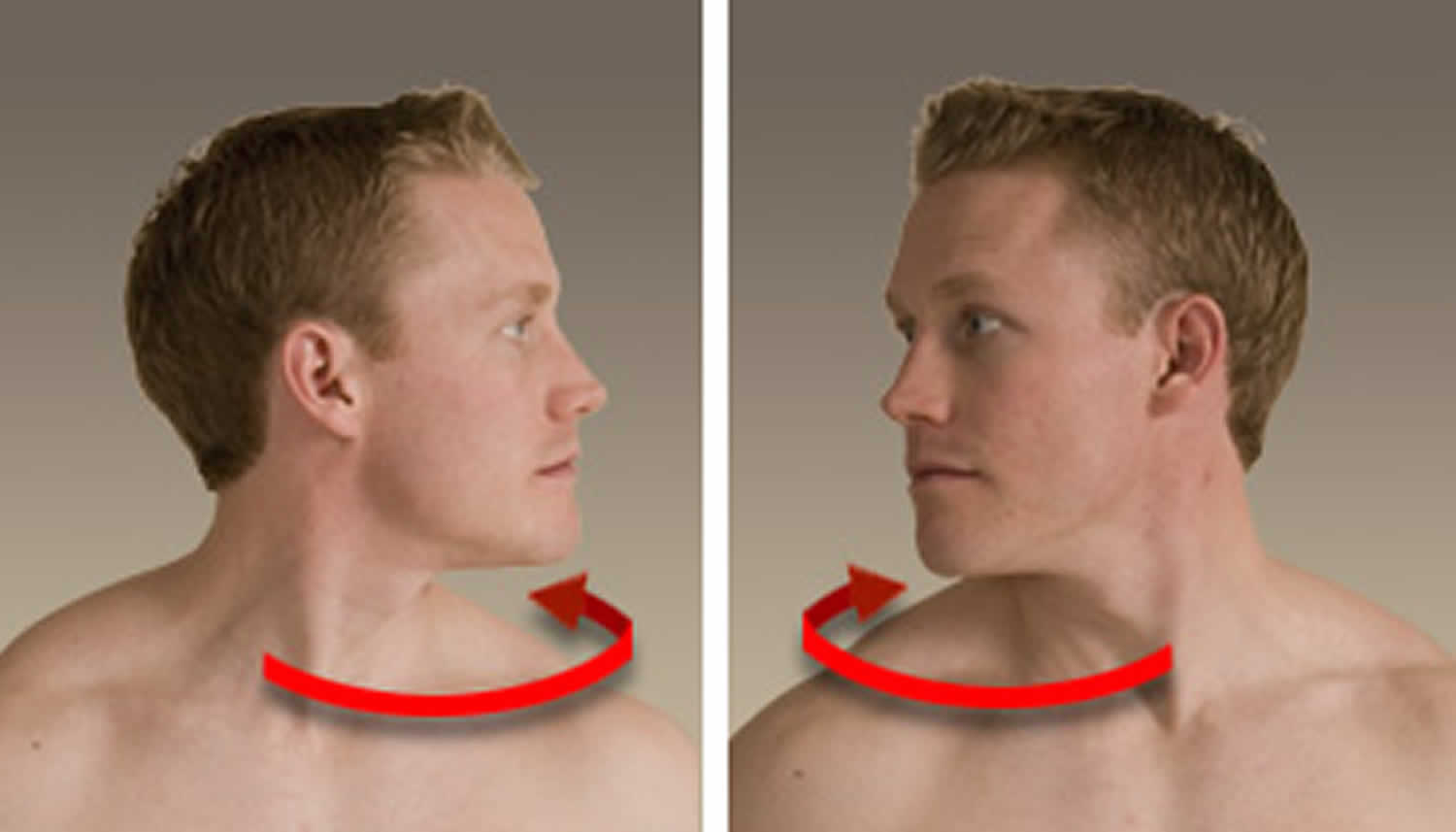

Neck rotation

- Sit in a firm chair, or stand up straight.

- Keeping your chin level, turn your head to the right, and hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

- Turn your head to the left and hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

- Repeat 2 to 4 times to each side.

Figure 2. Neck rotation

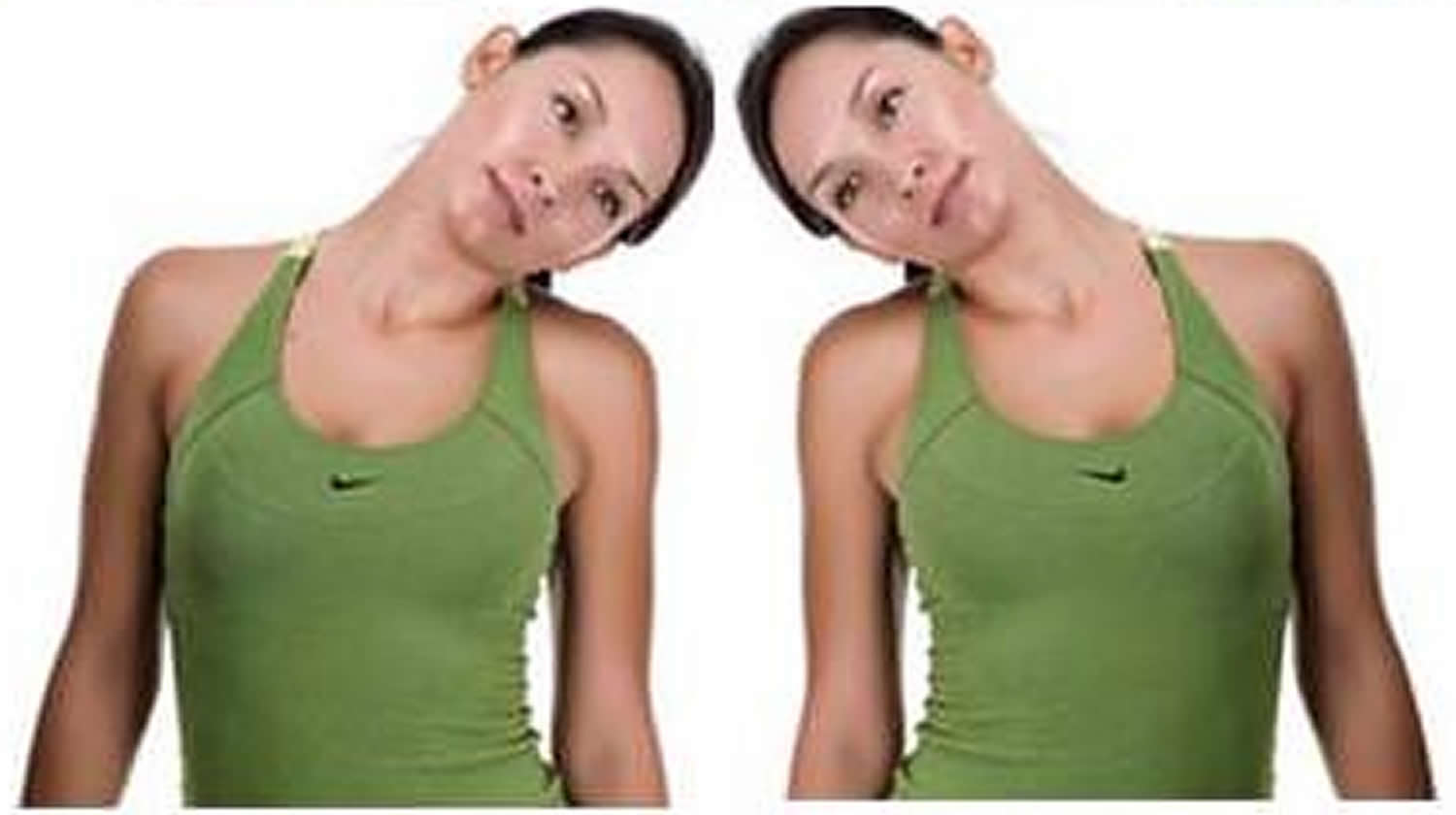

Neck stretches

- Look straight ahead, and tip your right ear to your right shoulder. Do not let your left shoulder rise up as you tip your head to the right.

- Hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

- Tilt your head to the left. Do not let your right shoulder rise up as you tip your head to the left.

- Hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

- Repeat 2 to 4 times to each side.

Figure 3. Neck stretches

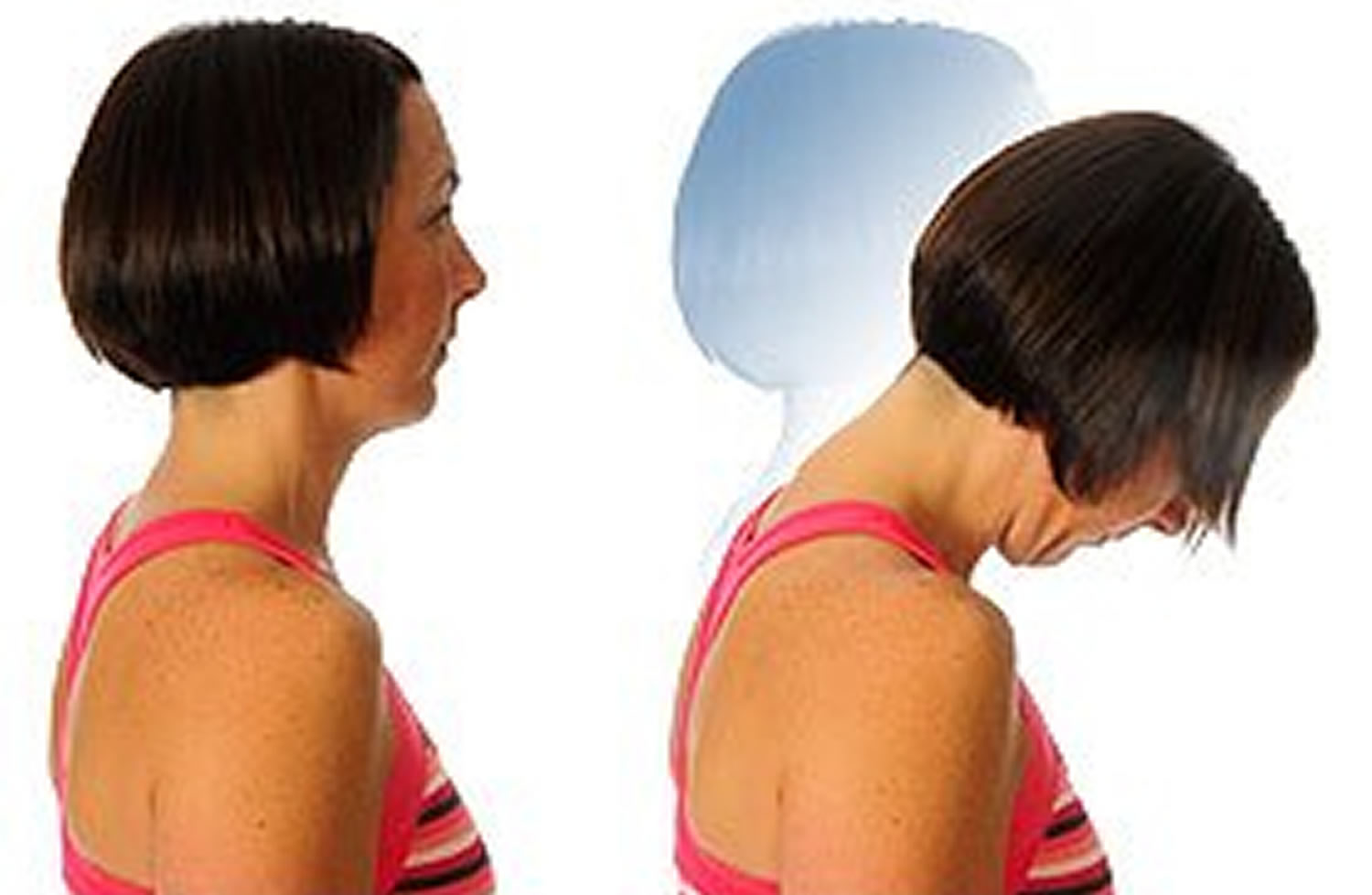

Forward neck flexion

- Sit in a firm chair, or stand up straight.

- Bend your head forward.

- Hold for 15 to 30 seconds.

- Repeat 2 to 4 times.

Figure 4. Forward neck flexion

Lateral (side) bend strengthening

- With your right hand, place your first two fingers on your right temple.

- Start to bend your head to the side while using gentle pressure from your fingers to keep your head from bending.

- Hold for about 6 seconds.

- Repeat 8 to 12 times.

- Switch hands and repeat the same exercise on your left side.

Figure 5. Lateral bend strengthening

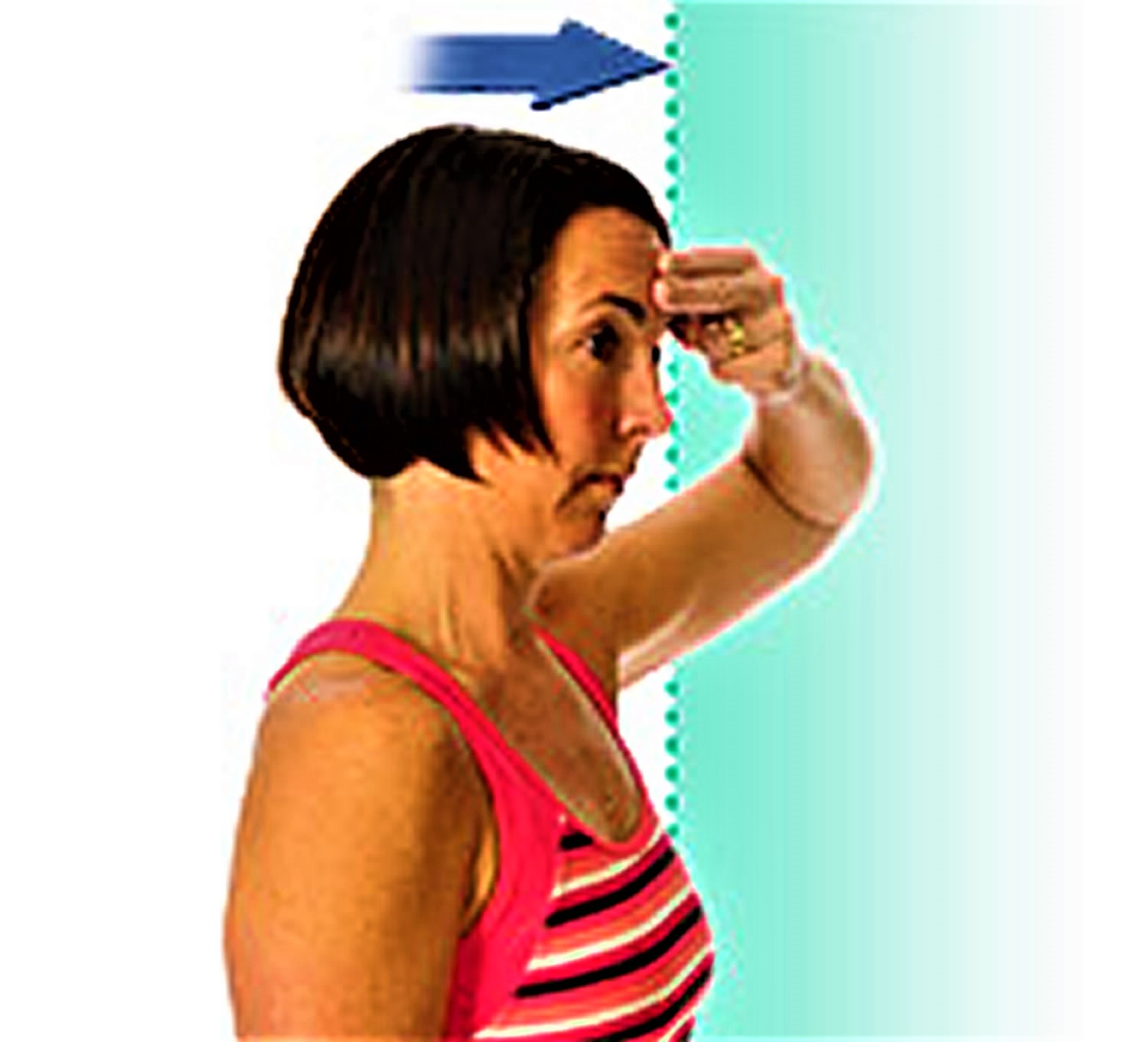

Forward bend strengthening

- Place your first two fingers of either hand on your forehead.

- Start to bend your head forward while using gentle pressure from your fingers to keep your head from bending.

- Hold for about 6 seconds.

- Repeat 8 to 12 times.

Figure 6. Forward bend strengthening

Neutral position strengthening

- Using one hand, place your fingertips on the back of your head at the top of your neck.

- Start to bend your head backward while using gentle pressure from your fingers to keep your head from bending.

- Hold for about 6 seconds.

- Repeat 8 to 12 times.

Figure 7. Neutral neck position strengthening

Chin tuck

- Lie on the floor with a rolled-up towel under your neck. Your head should be touching the floor.

- Slowly bring your chin toward your chest.

- Hold for a count of 6, and then relax for up to 10 seconds.

- Repeat 8 to 12 times.

Figure 8. Chin tuck

References- Johnson R. Anatomy of the cervical spine and its related structures. Torg JS, ed. Athletic Injuries to the Head, Neck, and Face. 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book; 1991. 371-83.

- Parke WW, Sherk HH. Normal adult anatomy. Sherk HH, Dunn EJ, Eismon FJ, et al, eds. The Cervical Spine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott Co; 1989. 11-32.

- McLain RF. Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints. Spine. 1994 Mar 1. 19(5):495-501.

- Bogduk N, Twomey L. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.

- Dreyfus P. The cervical spine: Non-surgical care Presented at: The Tom Landry Sports Medicine and Research Center; April 8, 1993; Dallas, Texas.

- Mendel T, Wink CS, Zimny ML. Neural elements in human cervical intervertebral discs. Spine. 1992 Feb. 17(2):132-5.

- Panjabi MM, Oxland TR, Parks EH. Quantitative anatomy of cervical spine ligaments. Part I. Upper cervical spine. J Spinal Disord. 1991 Sep. 4(3):270-6.

- Fielding JW, Cochran GB, Lawsing JF 3rd, Hohl M. Tears of the transverse ligament of the atlas. A clinical and biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974 Dec. 56(8):1683-91.

- Panjabi MM, Vasavada A, White A III. Cervical spine biomechanics. Semin Spine Surg. 1993. 5:10-6.

- Hoving JL, Koes BW, de Vet HC, et al. Manual therapy, physical therapy, or continued care by a general practitioner for patients with neck pain. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:713–22.

- Liang ZH, Di Z, Jiang S, et al. The optimized acupuncture treatment for neck pain caused by cervical spondylosis: a study protocol of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:107.

- Manchikanti L, Helm S, Singh V, et al. An algorithmic approach for clinical management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2009;12:E225–64.

- Falco FJ, Erhart S, Wargo BW, et al. Systematic review of diagnostic utility and therapeutic effectiveness of cervical facet joint interventions. ibid. 2009;12:323–44.