Cutaneous larva migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans also known as creeping eruption, is a parasitic skin infection caused by multiple types of hookworms larvae that usually infest cats, dogs and other animals 1. This is most commonly transmitted by animal feces depositing eggs in the soil, with larvae entering humans through direct contact with skin. Humans can be infected with the larvae by walking barefoot on sandy beaches or contacting moist soft soil that has been contaminated with animal feces. It is also known as creeping eruption as once infected, the larvae migrate under the skin’s surface and cause itchy red lines or tracks. Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly found in tropical and subtropical geographic areas and the southwestern United States. It has become an endemic in the Caribbean, Central America, South America, Southeast Asia, and Africa. However, the ease and the increasing incidence of foreign travel by the world’s population have no longer confined cutaneous larva migrans to these areas 2. Prevalence of cutaneous larva migrans is often highest during wet seasons. Tourists traveling to endemic areas who are affected have been tended to be younger 3.

Cutaneous larva migrans is distinguished from the cutaneous manifestation of Strongyloides stercoralis infection termed larva currens 1. The latter demonstrating fast movement through the skin. Other non-larval cutaneous migrations including loiasis, scabies, or larva with dermal penetration are also excluded from cutaneous larva migrans 4.

- Cutaneous larva migrans is classically seen in warmer climates including the southeast United States. Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

- Symptomatology includes a progressive migrating serpiginous rash commonly with pruritus. While the disease can affect any exposed area, the most common location is the feet.

- The natural progression of the disease is self-limited as the organisms are unable to produce a collagenase to penetrate the basement membrane and reach the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to reproduce. When treatment is given topical thiabendazole, oral albendazole, or ivermectin are the drugs of choice.

- Complications often arise from secondary bacterial superinfection or complications from inappropriate empiric therapy 3.

Cutaneous larva migrans is self-limiting; migrating larvae usually die after 5–6 weeks 5. Albendazole is very effective for treatment. Ivermectin is effective but not approved for this indication 5. Symptomatic treatment for frequent severe itching may be helpful.

Effective treatment is available to shorten the course of cutaneous larva migrans:

- Anthelmintics such as tiabendazole, albendazole, mebendazole and ivermectin are used. Topical thiabendazole is considered the treatment of choice for early, localised lesions. Oral treatment is given when the cutaneous larva migrans is widespread or topical treatment has failed. Itching is considerably reduced within 24–48 hours of starting antihelmintic treatment and within 1 week most lesions/tracts resolve.

- If these are unavailable, physical treatments such as liquid nitrogen cryotherapy or carbon dioxide laser may be used to destroy the larvae.

- Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may also be used with anthelminthics to provide symptomatic relief of itch.

- Secondary bacterial infection may require treatment with appropriate antibiotics.

Figure 1. Cutaneous larva migrans

Footnote: A 42-year-old man presented with an intensely pruritic eruption on his foot after a vacation in Nigeria. The eruption was migratory, moving a few millimeters to a few centimeters daily. Examination revealed a serpiginous, erythematous raised tract on his right foot.

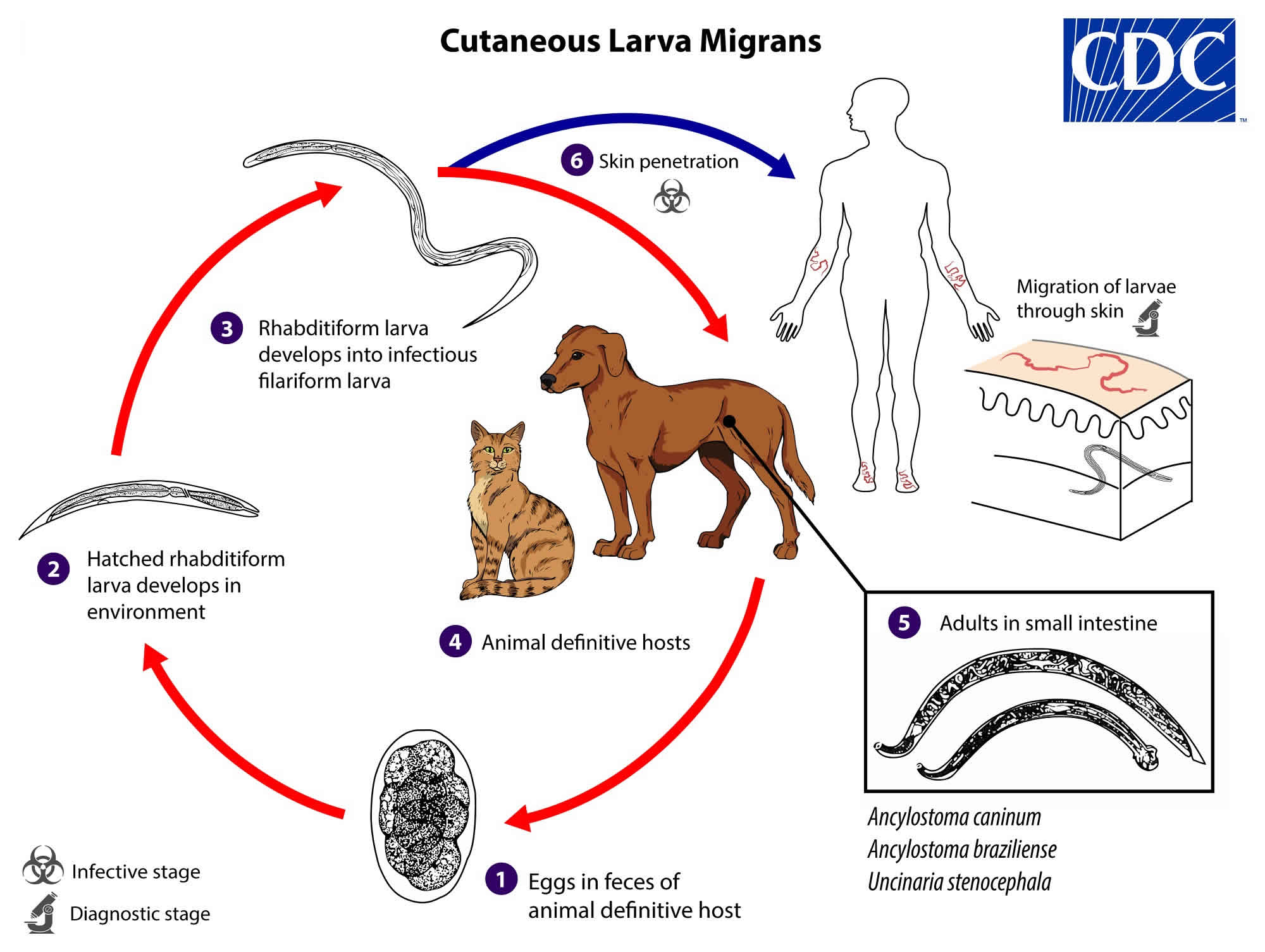

[Source 6 ]Cutaneous larva migrans life cycle

Cutaneous larva migrans has been associated with Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma braziliens, and Uncinaria stenocephala, which are all hookworms of dogs and cats. Bunostomum phlebotomum, a cattle hookworm, is also capable of causing short-lived cutaneous larva migrans in humans.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a zoonotic infection with hookworm species that do not use humans as a definitive host, the most common being Ancylostoma braziliense and Ancylostoma caninum. The cycle in the definitive host is very similar to the cycle for the human species, which involves tracheal migration to the small intestine. Some larvae become arrested in the tissues and serve as the source of infection for pups via transmammary (and possibly transplacental) routes. Mature hookworms reproduce in the small intestine, and eggs are passed in the animal definitive host’s stool (number #1), and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil (number #2) and after 5 to 10 days (and 2 molts) they become filariform (third-stage) larvae that are infective (number #3). These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions. On contact with the animal host (number #4), the larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the blood vessels to the heart and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed. The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the intestinal wall. Some larvae become arrested in the tissues, and serve as source of infection for pups via transmammary (and possibly transplacental) routes (number #5). Humans become infected when filariform larvae penetrate the skin (number #6). With most species, the larvae cannot mature further in the human host and migrate aimlessly within the epidermis, sometimes as much as several centimeters a day. Some larvae may become arrested in deeper tissue after skin migration.

Figure 2. Cutaneous larva migrans life cycle

Cutaneous larva migrans causes

Many types of hookworm can cause cutaneous larva migrans. Common causes are 7:

- Ancylostoma braziliense: hookworm of wild and domestic dogs and cats found in central and southern US, Central and South America, and the Caribbean

- Ancylostoma caninum: dog hookworm found in Australia

- Uncinaria stenocephala: dog hookworm found in Europe

- Bunostomum phlebotomum: cattle hookworm

Human hookworms Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus also can cause disease 8.

Who is at risk of cutaneous larva migrans?

People of all ages, sex and race can be affected by cutaneous larva migrans if they have been exposed to hookworm larvae. It is most commonly found in tropical or subtropical geographic locations. Groups at risk include those with occupations or hobbies that bring them into contact with warm, moist, sandy soil. These may include:

- Barefoot beachcombers and sunbathers

- Children in sandpits

- Farmers

- Gardeners

- Plumbers

- Hunters

- Electricians

- Carpenters

- Pest exterminators.

Most larva migrans seen in United States arises during overseas holidays, but it has rarely been reported in those who have never been out of the country.

Cutaneous larva migrans pathophysiology

Adult hookworms live in intestines of dogs and cats. Parasite eggs are shed in feces of infested animals to warm, moist, sandy soil and after deposition into the soil the larvae hatch within one day. Over the course of the proceeding week, these develop into infective larvae. Worms respond to physical vibration and increased temperature and move in a snake like fashion. On contact with human skin, the larvae can penetrate through hair follicles, cracks or even intact skin to infect the human host. Upon contacting a host organism penetrate the corneal layer by secreting a hyaluronidase. Between a few days and a few months after the initial infection, the larvae migrate beneath the skin. Despite burrowing through the superficial cutaneous layers, they are unable to penetrate the basement membrane to invade the dermis and to enter lymphatics are therefore are unable to complete their lifecycle. Hookworms subsequently die without reproducing, and disease is self-limited 8.

Cutaneous larva migrans prevention

Reduce contact with contaminated soil by wearing shoes and protective clothing and using barriers such as towels when seated on the ground.

Wearing shoes and taking other protective measures to avoid skin contact with sand or soil will prevent infection with zoonotic hookworms. Travelers to tropical and subtropical climates, especially where beach exposures are likely, should be advised to wear shoes and use protective mats or other coverings to prevent direct skin contact with sand or soil. Routine veterinary care of dogs and cats, including regular deworming, will reduce environmental contamination with zoonotic hookworm eggs and larvae. Prompt disposal of animal feces prevents eggs from hatching and contaminating soil — which makes it important for control of this parasitic infection.

Cutaneous larva migrans symptoms

Patient history often involves travel to endemic areas and a history of walking barefoot. Creeping eruption usually appears 1–5 days after skin penetration, but the incubation period may be ≥1 month. The most common initial finding is a small reddish papule that progresses to a serpiginous pruritic rash with a slow rate of progression from less than 1 to 2 cm per day and is associated with intense itchiness and mild swelling. Usual locations are the foot, spaces between the toes and buttocks, although any skin surface (hands, knees) coming in contact with contaminated soil can be affected. The initial presentation may vary depending on species. Disease from Ancylostoma braziliens manifests within 1 hour, while papular lesions may take days to appear when Uncinaria stenocephala is the organism that infects a person. Vesiculobullous disease may occur as well, and papulopustular inflammation of the follicles has been documented, although this is not common 9.

Cutaneous larva migrans complications

Cutaneous larva migrans complications include secondary infection most commonly with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcal species. Secondary impetiginization occurs in up to 8% of cases. If the infection is prolonged post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis has been reported. Although it is well accepted that larvae cannot penetrate the basement membrane of skin, visceral disease has been rarely reported. Larvae has been identified in sputum, found in viscera of a human host, and also found in skeletal musculature. Host response to infection has rarely occurred as erythema multiforme 10.

Cutaneous larva migrans diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually made clinically based on the history of recent travel to endemic areas in combination with a classic serpiginous rash. The rash is very pruritic, raised, and has a slower rate of millimeters up to 2 cm per day. This distinguishes it from other migrating infections. Blood tests are not necessary for diagnosis. Not only is eosinophilia found in less than 40% of patients with cutaneous larva migrans, but it is also not specific. Non-invasive optical coherence tomography has been used to establish diagnosis although this is not often used. Skin biopsy is occasionally performed and may reveal the nematode larvae within a circular canal. A biopsy is not sensitive, and while secondary changes and infiltrate assist in diagnosis, it is not necessary to confirm this clinical diagnosis 11.

Cutaneous larva migrans treatment

Cutaneous larva migrans is self-limiting. Humans are an accidental and ‘dead-end’ host so the hookworm larvae eventually die. The natural duration of the disease varies considerably depending on the species of larvae involved. In most cases, lesions will resolve without treatment within 4–8 weeks. However, if the infection is local, topical thiabendazole 10% solution or 15% ointment may be tried first 1. The cream is applied 2 to 3 times daily for 5 to 10 days. Small studies have shown improvement of pruritus may occur as early as 48 hours after beginning treatment, and cure rates as high as 98% within 10 days have been achieved. The largest advantage of topical therapy is lack of systemic absorption and side effects, but use is limited by multiple applications daily, and utility is less valuable with multiple lesions.

Local disease has historically been treated with cryotherapy. However, freezing the leading edge of the skin with either liquid nitrogen, solid carbon dioxide, or ethylene chloride spray has been shown to be largely ineffective and should be avoided.

For multiple lesions or severe infestation albendazole and ivermectin are first-line systemic therapies. Oral albendazole, 400 mg daily for 3 to 5 days, is very effective with cure rates nearing 100%. Some studies show that a 7-day course of albendazole may decrease the rates of recurrent disease. Oral ivermectin is also effective, and its advantage is a patient only has to take a one-time dose of 12 mg by mouth. Cure rates near 100% with ivermectin administration.

Mebendazole is another anti-helminthic agent; however, it has poor bioavailability, absorption, and subsequently poor efficacy and should not be used as a first line medication. Also ineffective include topical steroids, oral steroids, and antibiotics. While systemic corticosteroids may reduce itching, the side-effect profile limits usefulness.

In addition to pharmacologic therapy, banning dogs from beaches may decrease deposition of larvae into the soil. Notably, towels do not consistently protect against transmission but wearing protective footwear can be effective 3.

Cutaneous larva migrans prognosis

Cutaneous larva migrans is often self-limited, and resolution without treatment is the rule rather than the exception. However, migration may continue for months, and during this time, pruritus may be severe, often interfering with sleep. Treatment, topical or systemic results in cure rates near 100%, and although recurrence can occur, it is also well prevented and responsive to systemic therapy 9.

References- Maxfield L, Crane JS. Cutaneous Larva Migrans. [Updated 2019 Mar 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507706

- González F CG, Galilea O NM, Pizarro C K. [Autochthonous cutaneous larva migrans in Chile. A case report]. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2015 Oct 8.

- Kincaid L, Klowak M, Klowak S, Boggild AK. Management of imported cutaneous larva migrans: A case series and mini-review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015 Sep-Oct;13(5):382-7.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008 May;8(5):302-9.

- Cutaneous Larva Migrans. Chapter 4 Travel-Related Infectious Diseases. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/cutaneous-larva-migrans

- Creeping Eruption — Cutaneous Larva Migrans. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:e16 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm1509325

- Cutaneous larva migrans. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-larva-migrans/

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):326-33.

- Veraldi S, Persico MC, Francia C, Nazzaro G, Gianotti R. Follicular cutaneous larva migrans: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Dermatol. 2013 Mar;52(3):327-30.

- Feldmeier H, Singh Chhatwal G, Guerra H. Pyoderma, group A streptococci and parasitic skin diseases — a dangerous relationship. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2005 Aug;10(8):713-6.

- Jacobson CC, Abel EA. Parasitic infestations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007 Jun;56(6):1026-43.