Cerebrovascular accident

CVA or cerebrovascular accident is the medical term for a stroke. A stroke also called cerebral infarction, is a serious life-threatening medical condition that occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is cut off or or when a blood vessel in the brain bursts, spilling blood into the spaces surrounding brain cells. Within minutes, brain cells begin to die. If brain cells die or are damaged because of a stroke, symptoms occur in the parts of the body that these brain cells control. Examples of stroke symptoms include sudden weakness; paralysis or numbness of the face, arms, or legs (paralysis is an inability to move); trouble speaking or understanding speech; and trouble seeing in one or both eyes; sudden trouble with walking, dizziness, or loss of balance or coordination; or sudden severe headache with no known cause.

- Stroke is a medical emergency and urgent treatment is essential to reduce brain damage and other complications.

- A stroke can cause lasting brain damage, long-term disability, or even death.

- Stroke is the no. 3 cause of death in the United States. More than 140,000 people die each year from stroke in the United States.

- Stroke is the leading cause of serious, long-term disability in the United States.

- Each year, approximately 795,000 people suffer a stroke. About 600,000 of these are first attacks, and 185,000 are recurrent attacks.

- Nearly three-quarters of all strokes occur in people over the age of 65. The risk of having a stroke more than doubles each decade after the age of 55.

- Strokes can and do occur at ANY age. Nearly one fourth of strokes occur in people under the age of 65.

- Stroke death rates are higher for African-Americans than for whites, even at younger ages.

- On average, someone in the United States has a stroke every 40 seconds.

- Stroke accounted for about one of every 17 deaths in the United States in 2006. Stroke mortality for 2005 was 137,000.

- The risk of ischemic stroke in current smokers is about double that of nonsmokers after adjustment for other risk factors.

- Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an independent risk factor for stroke, increasing risk about five-fold.

- High blood pressure is the most important risk factor for stroke.

The sooner a person receives treatment for a stroke, the less damage is likely to happen.

If you suspect that you or someone else is having a stroke, call your local emergency number immediately and ask for an ambulance.

Generally there are three treatment stages for stroke: prevention, therapy immediately after the stroke and post-stroke rehabilitation. Therapies to prevent a first or recurrent stroke are based on treating an individual’s underlying risk factors for stroke, such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and diabetes. Acute stroke therapies try to stop a stroke while it is happening by quickly dissolving or removing the blood clot causing an ischemic stroke or by stopping the bleeding of a hemorrhagic stroke. Post-stroke rehabilitation helps individuals overcome disabilities that result from stroke damage. Medication or drug therapy is the most common treatment for stroke. The most popular classes of drugs used to prevent or treat stroke are antithrombotics (antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants) and drugs that break up or dissolve blood clots, called thrombolytics.

The main symptoms of stroke can be remembered with the word F.A.S.T.:

- Face – the face may have dropped on one side, the person may not be able to smile, or their mouth or eye may have dropped.

- Arms – the person with suspected stroke may not be able to lift both arms and keep them there because of weakness or numbness in one arm.

- Speech – their speech may be slurred or garbled, or the person may not be able to talk at all despite appearing to be awake.

- Time – it’s time to dial your local emergency number immediately if you see any of these signs or symptoms.

If you have any of these symptoms or if you suspect someone else is having a stroke, you must get to a hospital quickly to begin treatment. Acute stroke therapies try to stop a stroke while it is happening by quickly dissolving the blood clot or by stopping the bleeding. The longer a stroke goes untreated, the greater the potential for brain damage and disability.

Post-stroke rehabilitation helps individuals overcome disabilities that result from stroke damage. Drug therapy with blood thinners is the most common treatment for stroke.

Types of cerebrovascular accident

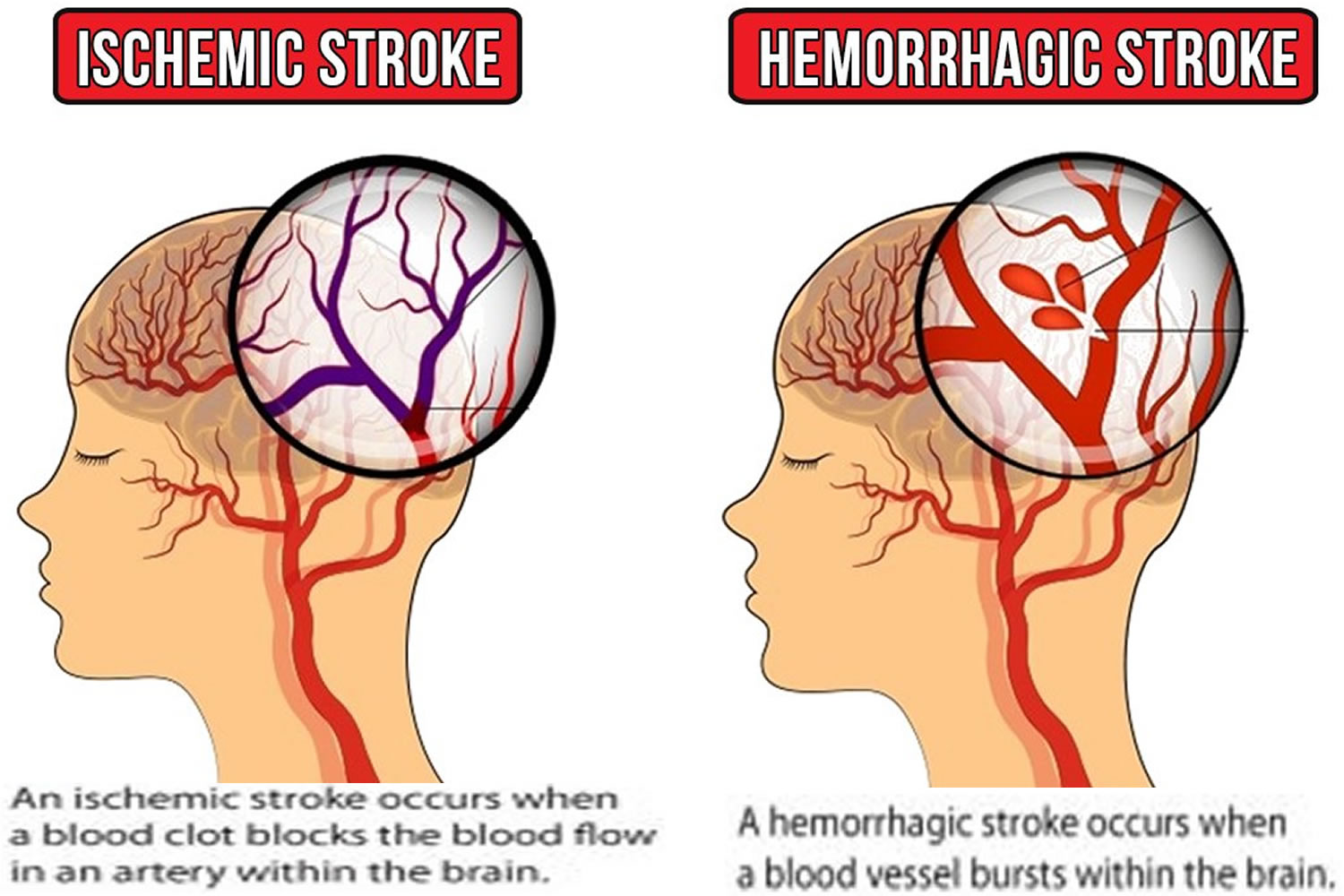

There are two kinds of stroke:

- Ischemic stroke is the more common kind of stroke caused by a blood clot that blocks or plugs a blood vessel in the brain.

- Hemorrhagic stroke occurs if an artery in the brain leaks blood or ruptures (breaks open) and bleeds into the surrounding brain. The blood accumulates and compresses the surrounding brain tissue. The pressure from the leaked blood damages brain cells.

- “Mini-strokes” or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), occur when the blood supply to the brain is briefly interrupted.

Ischemic stroke

About 85 percent of strokes are ischemic strokes. Ischemic strokes occur when the arteries to your brain become narrowed or blocked, causing severely reduced blood flow (ischemia). The most common ischemic strokes include:

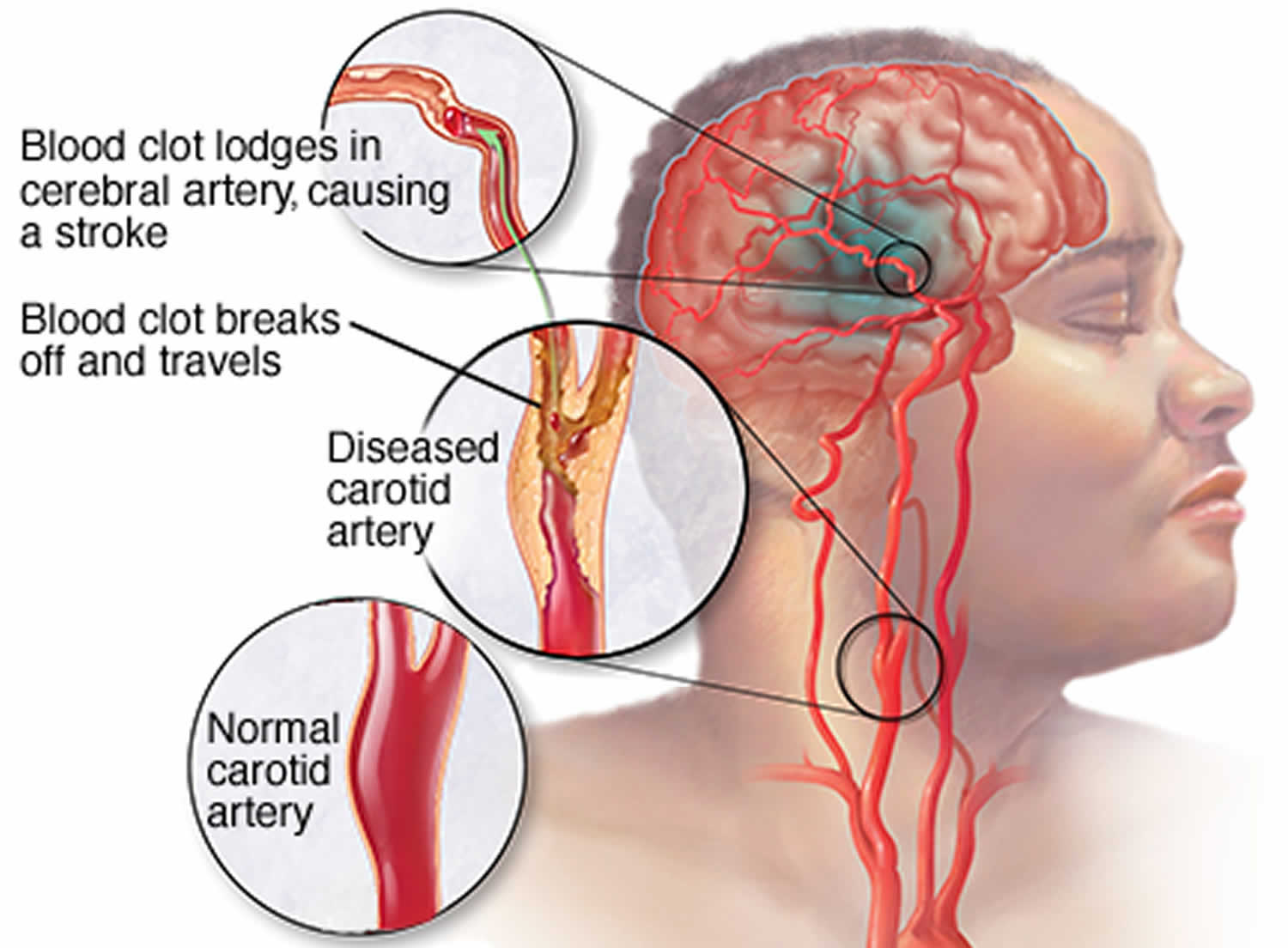

- Thrombotic stroke. A thrombotic stroke occurs when a blood clot (thrombus) forms in one of the arteries that supply blood to your brain. A clot may be caused by fatty deposits (plaque) that build up in arteries and cause reduced blood flow (atherosclerosis) or other artery conditions.

- Embolic stroke. An embolic stroke occurs when a blood clot or other debris forms away from your brain — commonly in your heart and large arteries of the upper chest and neck — and is swept through your bloodstream to lodge in narrower brain arteries. This type of blood clot is called an embolus. A second important cause of embolism is an irregular heartbeat, known as atrial fibrillation. It creates conditions where clots can form in the heart, dislodge and travel to the brain.

Figure 1. Ischemic stroke

Hemorrhagic stroke

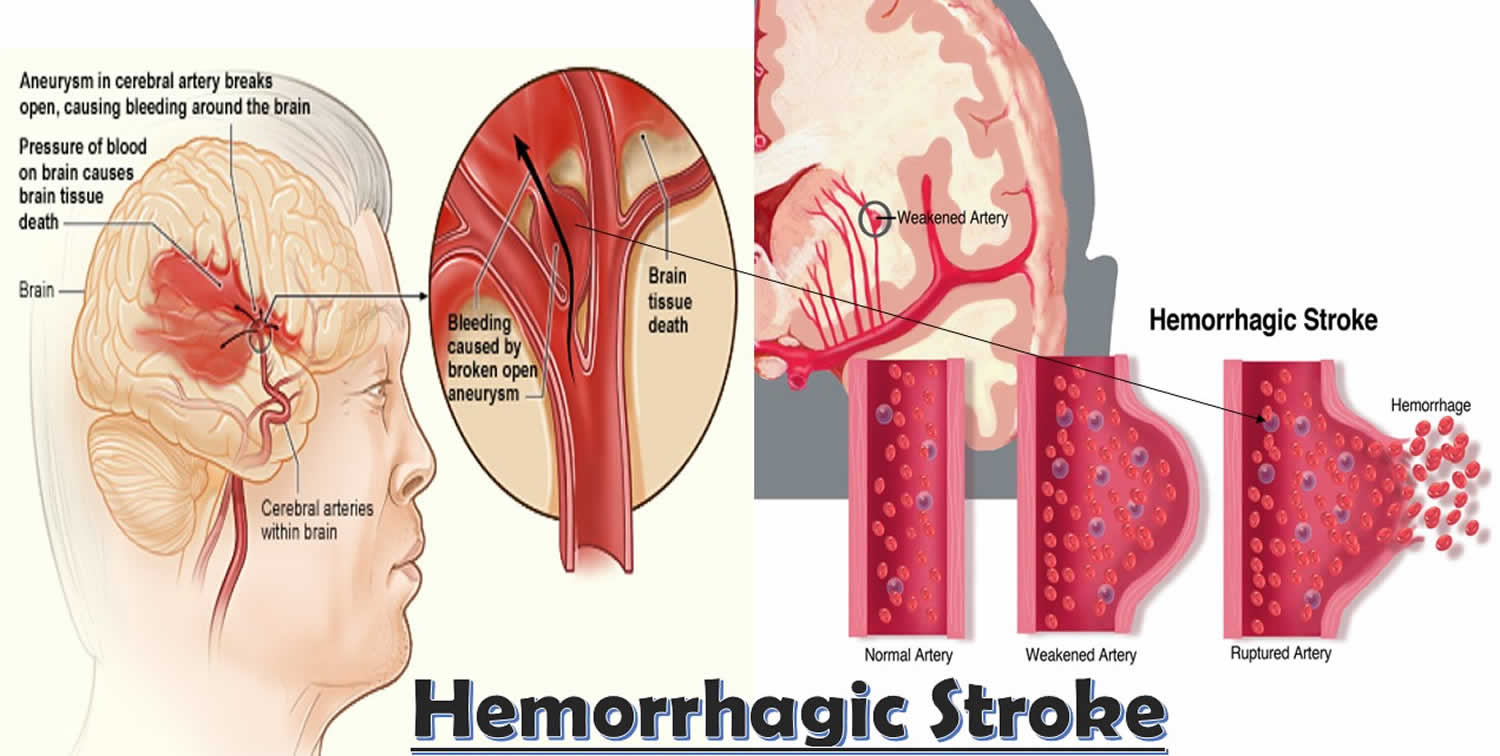

Hemorrhagic stroke occurs when a blood vessel in your brain leaks or ruptures. Brain hemorrhages can result from many conditions that affect your blood vessels, including uncontrolled high blood pressure (hypertension), overtreatment with anticoagulants and weak spots in your blood vessel walls (aneurysms).

A less common cause of hemorrhage is the rupture of an abnormal tangle of thin-walled blood vessels (arteriovenous malformation) present at birth. Types of hemorrhagic stroke include:

- Intracerebral hemorrhage. In an intracerebral hemorrhage, a blood vessel in the brain bursts and spills into the surrounding brain tissue, damaging brain cells. Brain cells beyond the leak are deprived of blood and also damaged.

High blood pressure, trauma, vascular malformations, use of blood-thinning medications and other conditions may cause an intracerebral hemorrhage.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage. In a subarachnoid hemorrhage, an artery on or near the surface of your brain bursts and spills into the space between the surface of your brain and your skull. This bleeding is often signaled by a sudden, severe headache.

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is commonly caused by the bursting of a small sack-shaped or berry-shaped outpouching on an artery known as an aneurysm. After the hemorrhage, the blood vessels in your brain may widen and narrow erratically (vasospasm), causing brain cell damage by further limiting blood flow.

Figure 2. Hemorrhagic stroke

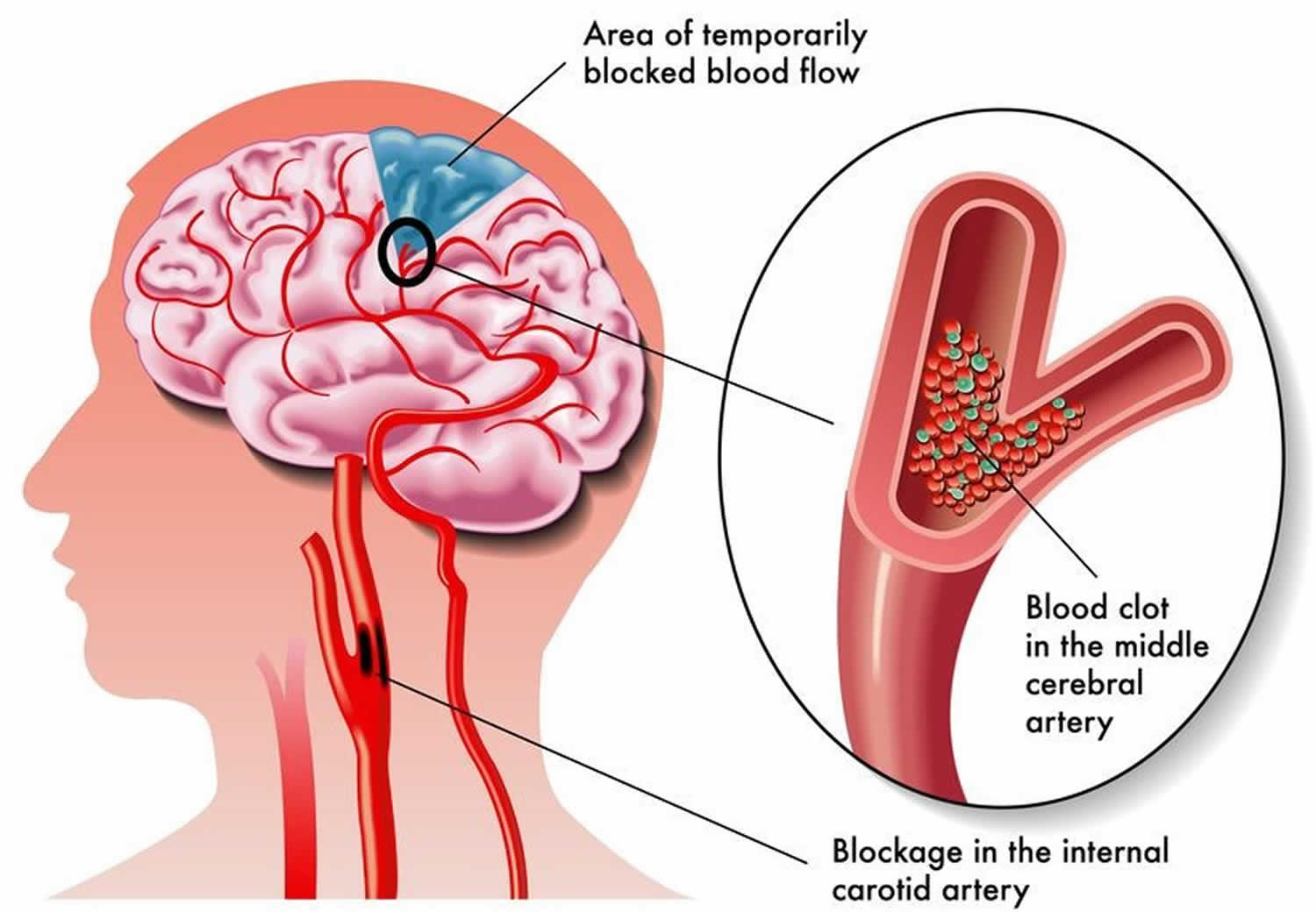

Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) — also known as a mini stroke — is a brief period of symptoms similar to those you’d have in a stroke. A temporary decrease in blood supply to part of your brain causes TIA, which often last less than five minutes.

Like an ischemic stroke, a TIA occurs when a clot or debris blocks blood flow to part of your brain. A TIA doesn’t leave lasting symptoms because the blockage is temporary.

Seek emergency care even if your symptoms seem to clear up. Having a TIA puts you at greater risk of having a full-blown stroke, causing permanent damage later. If you’ve had a TIA, it means there’s likely a partially blocked or narrowed artery leading to your brain or a clot source in the heart.

It’s not possible to tell if you’re having a stroke or a TIA based only on your symptoms. Up to half of people whose symptoms appear to go away actually have had a stroke causing brain damage.

Figure 3. Transient ischemic attack (TIA) or mini stroke

Brain stem stroke

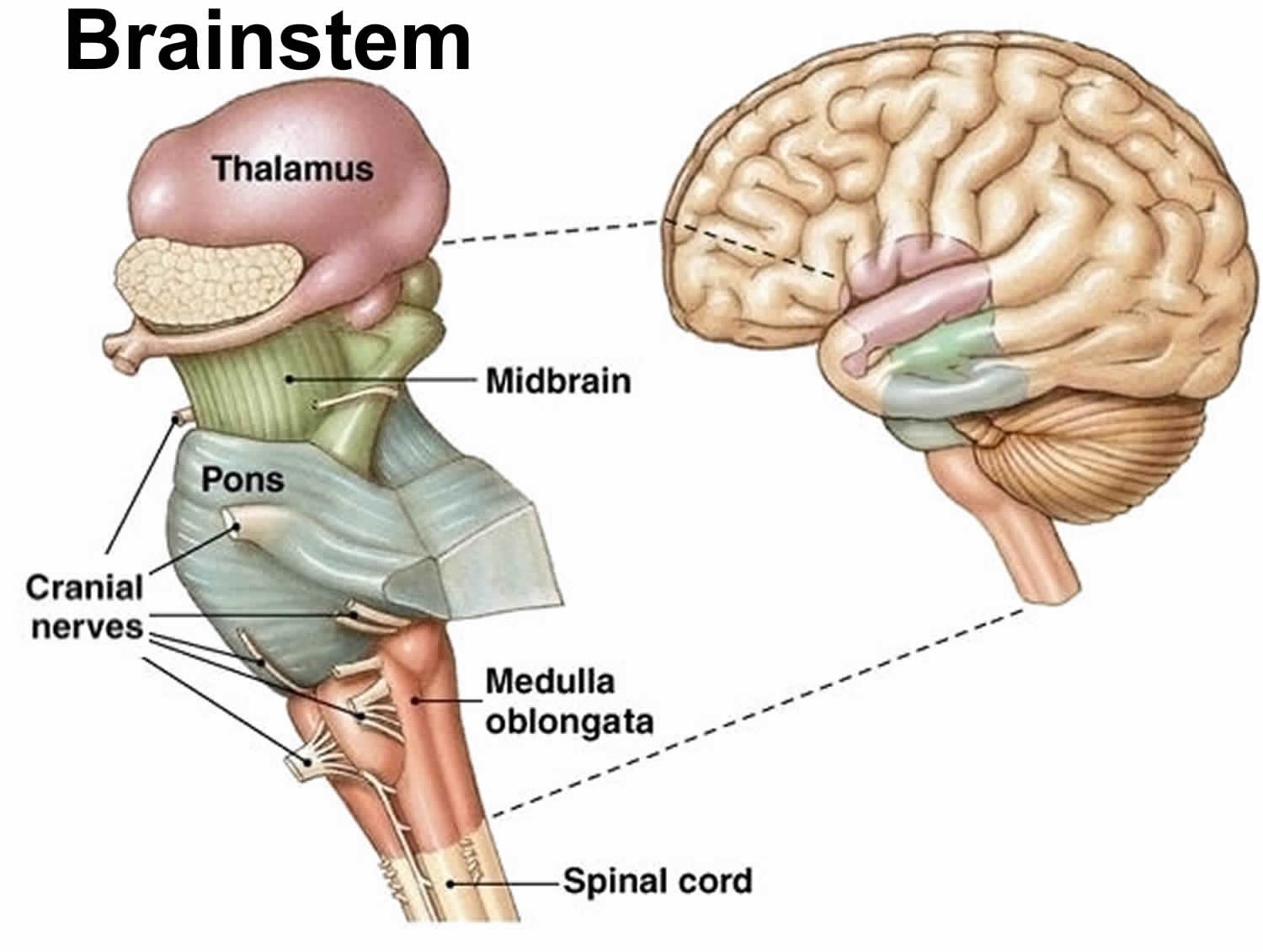

The brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata, situated in the posterior part of the brain (Figure 4). The brainstem is a connection between the cerebrum, the cerebellum, and the spinal cord. Only a half-inch in diameter, the brain stem is responsible for multiple critical functions, including breathing, heart rhythm, blood pressure control, consciousness, and sleep-wake cycle 1. The cranial nerve nuclei that are present in the brainstem have a crucial role in vision, balance, hearing, swallowing, taste, speech, motor, and sensory supply to the face. The white matter of the brainstem carries most of the signals between the brain and the spinal cord and helps with its relay and processing. All motor control for the body flows through it. Brain stem strokes can impair any or all of these functions. More severe brain stem strokes can cause locked-in syndrome, a condition in which survivors can move only their eyes 2.

Brain stem stroke can be due to the loss of blood supply (ischemic stroke) or bleeding (hemorrhagic stroke). The most common causes for brainstem stroke are atherosclerosis, thromboembolism, lipohylanosis, tumor, arterial dissection, and trauma. In medulla oblongata infarcts, 73% are due to stenosis of the vertebral artery, 26% due to arterial dissection, and rest being caused by other causes like cardioembolic 3. However, the number of infarcts due to cardioembolic etiology increase to 8% in pontine infarcts and 20% to 46% in midbrain infarcts 4.

Risk factors for brain stem stroke are the same as for strokes in other areas of the brain: high blood pressure, diabetes, metabolic syndromes, hyperlipidemia, tobacco use, obesity, history of ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, smoking, sleep apnea, lack of physical activity, use of oral contraceptives, fibromuscular dysplasia, trauma, and spinal manipulation 5, 6, 7. Similarly, brain stem strokes can be caused by a clot or a hemorrhage. There are also rare causes, like injury to an artery due to sudden head or neck movements.

Brain stem stroke is an area of tissue death resulting from a lack of oxygen supply to any part of the brainstem. Brainstem stroke accounts for about 9 to 21.9% of stroke 8:244-8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.2_part_1.244)). Brain stem strokes can have complex symptoms, and they can be difficult to diagnose. A person may have vertigo, dizziness and severe imbalance without the hallmark of most strokes such as weakness on one side of the body. The symptoms of vertigo dizziness or imbalance usually occur together; dizziness alone is not a sign of stroke. A brain stem stroke can also cause double vision, slurred speech and decreased consciousness.

Due to the high density of nuclei and fibers running through the brainstem, the lesion in various structures gives rise to different signs and symptoms. Variously named stroke and stroke syndromes have been described in the literature.

- The ‘top-of-the-basilar’ syndrome: Also known as the rostral brainstem infarction. It results in alternating disorientation, hypersomnolence, unresponsiveness, hallucination, and behavioral abnormalities along with visual, oculomotor deficits, and cortical blindness 9. Occurs due to occlusion of the distal basilar artery and its perforators.

- Ondine’s syndrome: Affects the brainstem response centers for automatic breathing. It results in complete breathing failure during sleep but normal ventilation when awake 9. The blood supply affected is the pontine perforating arteries, branches of the basilar artery, anterior inferior cerebellar artery, or the superior cerebellar artery.

- One-and-a-half syndrome: Affects the paramedian pontine reticular formation and medial longitudinal fasciculus. It results in the ipsilateral conjugate gaze palsy and internuclear ophthalmoplegia 10. The blood supply affected is the pontine perforating arteries and branches of the basilar artery.

- Claude syndrome: Affects the fibers from CN III, the rubrodentate fibers, corticospinal tract fibers, and corticobulbar fibers. It results in ipsilateral CN III palsy, contralateral hemiplegia of lower facial muscles, tongue, shoulder, upper and lower limb along with contralateral ataxia. The blood supply involved is from the posterior cerebral artery.

- Dorsal midbrain syndrome (Benedikt): Also known as paramedian midbrain syndrome, affects the fibers from CN III and the red nucleus. It results in ipsilateral CN III palsy, contralateral choreoathetosis, tremor, and ataxia. The blood supply involved comes from the posterior cerebral artery and paramedian branches of the basilar artery.

- Nothnagel syndrome: Affects the fibers from CN III and the superior cerebellar peduncle. It results in ipsilateral CN III palsy and ipsilateral limb ataxia. It can be due to quadrigeminal neoplasms and is often bilateral.

- Ventral midbrain syndrome (Weber): Affects the fibers from CN III, cerebral peduncle (corticospinal and corticobulbar tract), and substantia nigra. It results in ipsilateral CN III palsy, contralateral hemiplegia of lower facial muscles, tongue, shoulder, upper and lower limb. The involvement of substantial nigra is present can result in a contralateral movement disorder. The blood supply affected is the paramedian branches of the posterior cerebral artery.

Pontine syndromes 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

- Brissaud-Sicard syndrome: Affects the CN VII nucleus and corticospinal tract. It results in ipsilateral facial cramps and contralateral upper and lower limb hemiparesis. The blood supply affected is the posterior circulation. Rarely, the syndrome can arise due to brainstem glioma.

- Facial colliculus syndrome: Affects the CN VI nucleus, the CN VII nucleus, and fibers and the medial longitudinal fasciculus. It results in lower motor neuron CN VII palsy, diplopia, and horizontal conjugate. It can occur due to neoplasm, multiple sclerosis, or viral infection.

- Gasperini syndrome: Affects the nuclei of CN V, VI, VII, VIII, and the spinothalamic tract. It results in ipsilateral facial sensory loss, ipsilateral impaired eye abduction, ipsilateral impaired eye abduction, ipsilateral nystagmus, vertigo, and contralateral hemi-sensory impairment. The blood supply involved derives from the pontine branches of the basilar artery and long circumferential artery of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Gellé syndrome: Affects the CN VII, VIII, and corticospinal tract. It results in ipsilateral facial palsy, ipsilateral hearing loss, and contralateral hemiparesis.

- Grenet syndrome: Affects CN V lemniscus, CN VII fibers, and spinothalamic tract. It results in altered sensation in the ipsilateral face, contralateral upper, and contralateral lower limbs. It can arise due to neoplasm.

- Inferior medial pontine syndrome (Foville syndrome): Also known as the lower dorsal pontine syndrome, affects corticospinal tract, medial lemniscus, middle cerebellar peduncle, and the nucleus of CN VI and VII. It results in contralateral hemiparesis, contralateral loss of proprioception & vibration, ipsilateral ataxia, ipsilateral facial palsy, lateral gaze paralysis, and diplopia. The blood supply affected is from branches of the basilar artery.

- Lateral pontine syndrome (Marie-Foix syndrome): Affects the nuclei of CN VII, & VIII, corticospinal tract, spinothalamic tract, and cerebellar tracts. It results in contralateral hemiparesis, contralateral loss of proprioception & vibration, ipsilateral limb ataxia, ipsilateral facial palsy, lateral hearing loss, vertigo, and nystagmus. The blood supply affected is the perforating branches of the basilar artery and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Locked-in syndrome: Affects upper ventral pons, including corticospinal tract, corticobulbar tract, and CN VI nuclei. It results in quadriplegia, bilateral facial palsy, and horizontal eye palsy. The patient can move the eyes vertically, blink, and has an intact consciousness. The blood supply affected is the middle and proximal segments of the basilar artery.

- Raymond syndrome: Affects the CN VI fibers, corticospinal tract, and corticofacial fibers. It results in an ipsilateral lateral gaze palsy, contralateral hemiparesis, and facial palsy. The blood supply involved is from the branches of the basilar artery.

- Upper dorsal pontine syndrome (Raymond-Cestan): Affects the longitudinal medial fasciculus, medial lemniscus, spinothalamic tract, CN V fibers and nuclei, superior and middle cerebellar peduncle. It results in ipsilateral ataxia, coarse intension tremors, sensory loss in the face, weakness of mastication, contralateral loss of all sensory modalities. The blood supply involved is from the circumferential branches of the basilar artery.

- Ventral pontine syndrome (Millard-Gubler): Affects the CN VI & VII and corticospinal tract. It results in ipsilateral lateral rectus palsy, diplopia, ipsilateral facial palsy, and contralateral hemiparesis of upper and lower limbs. The blood supply involved derives from the branches from the basilar artery.

Medulla oblongata 19, 20, 21, 22

- Avellis syndrome: Affects the pyramidal tract and nucleus ambiguus. It results in ipsilateral palatopharyngeal palsy, contralateral hemiparesis, and contralateral hemi-sensory impairment. The blood supply affected is the vertebral arteries.

- Babinski-Nageotte syndrome: Also known as the Wallenberg with hemiparesis, affects the spinal fiber and nucleus of CN V, nucleus ambiguus, lateral spinothalamic tract, sympathetic fibers, afferent spinocerebellar tracts, and corticospinal tract. It results in ipsilateral facial loss of pain & temperature, ipsilateral palsy of the soft palate, larynx & pharynx, ipsilateral Horner syndrome, ipsilateral cerebellar hemi-ataxia, contralateral hemiparesis, and contralateral loss of body pain and temperature. The blood supply involved is from the intracranial portion of the vertebral artery and branches from the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Cestan-Chenais syndrome: It affects the spinal fiber and nucleus of CN V, nucleus ambiguus, lateral spinothalamic tract, sympathetic fibers, and corticospinal tract. It results in ipsilateral facial loss of pain and temperature, ipsilateral palsy of the soft palate, larynx & pharynx, ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, contralateral hemiparesis, contralateral loss of body pain & temperature, and contralateral tactile hypesthesia. The blood supply affected is the intracranial portion of the vertebral artery and branches from the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Hemimedullary syndrome (Reinhold syndrome): Affects the nucleus & fiber of CN V, CN XII nucleus ambiguus, lateral spinothalamic tract, sympathetic fibers, afferent spinocerebellar tracts, corticospinal tract, and medial lemniscus. It results in ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, ipsilateral facial loss of pain & temperature, ipsilateral palsy of soft palate, larynx & pharynx, ipsilateral tongue weakness, ipsilateral cerebellar hemi-ataxia, contralateral hemiparesis, and contralateral face sparing hemihypesthesia. The blood supply involved is from the ipsilateral vertebral artery, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, and branches from the anterior spinal artery.

- Jackson syndrome: Affects CN XII and pyramidal tract. It results in ipsilateral palsy of the tongue and contralateral hemiparesis. The blood supply involved is from the branches from the anterior spinal artery.

- Lateral medullary syndrome (Wallenberg syndrome): Affects the spinal nucleus & fiber of CN V, nucleus ambiguus, lateral spinothalamic tract, sympathetic fibers, inferior cerebellar peduncle, and vestibular nuclei 23. It results in ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, ipsilateral facial loss of pain & temperature, ipsilateral palsy of soft palate, larynx & pharynx, ipsilateral cerebellar hemi-ataxia, contralateral loss of body pain & temperature, nystagmus, dysarthria, dysphagia, and hyperacusis. The blood supply affected is the vertebral artery and branches from the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Medial medullary syndrome (Dejerine syndrome): Affects the fibers of CN XII, corticospinal tract, and medial lemniscus spinal. Results in ipsilateral tongue weakness, ipsilateral loss of proprioception & vibration, contralateral hemiparesis, and contralateral face sparing hemihypesthesia. The blood supply affected is the branches from the vertebral artery and the anterior spinal artery.

- Schmidt syndrome: Affects the fibers and nuclei of CN IX, X, XI, and pyramidal system. It results in ipsilateral palsy of the vocal cords, soft palate, trapezius, & sternocleidomastoid muscle, and contralateral spastic hemiparesis. The blood supply involved involves branches from the vertebral artery, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery the anterior spinal artery.

- Spiller syndrome: Affects the fibers and nucleus of CN XII, corticospinal tract, and medial lemniscus spinal along with medial hemi-medulla. Results in ipsilateral tongue weakness, ipsilateral loss of proprioception & vibration, contralateral hemiparesis, and contralateral face sparing hemihypesthesia. The blood supply involved is from the branches from the vertebral artery and the anterior spinal artery.

- Tapia syndrome: Affects the nucleus ambiguus, CN XII, and pyramidal tract. It results in ipsilateral palsy of the trapezius, sternocleidomastoid muscle, & half of the tongue, dysphagia, dysphonia, and contralateral spasmodic hemiparesis. The blood supply involved is from the branches from the vertebral artery, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery the anterior spinal artery.

- Vernet syndrome: Affects the CN IX, X, and XI. It occurs due to compression in the jugular foramen

Like all strokes, brain stem strokes produce a wide spectrum of deficits and recovery. Whether a survivor has minor or severe deficits depends on the location of the stroke within the brain stem, the extent of injury and how quickly treatment is provided.

If a stroke in the brain stem results from a clot, the faster blood flow can be restored, the better the chances for recovery. Patients should receive treatment as soon as possible for the best recovery.

Figure 4. Brain stem stroke

CVA symptoms

The signs and symptoms of a stroke vary from person to person, but usually begin suddenly.

As different parts of your brain control different parts of your body, your symptoms will depend on the part of your brain affected and the extent of the damage.

The main stroke symptoms can be remembered with the word F.A.S.T.:

- Face – the face may have dropped on one side, the person may not be able to smile, or their mouth or eye may have drooped.

- Arms – the person with suspected stroke may not be able to lift both arms and keep them there because of weakness or numbness in one arm.

- Speech – their speech may be slurred or garbled, or the person may not be able to talk at all despite appearing to be awake.

- Time – it’s time to dial your local emergency immediately if you notice any of these signs or symptoms.

It’s important for everyone to be aware of these signs and symptoms, particularly if you live with or care for somebody in a high-risk group, such as someone who is elderly or has diabetes or high blood pressure.

Other possible symptoms of a stroke

Symptoms in the F.A.S.T. test identify most strokes, but occasionally a stroke can cause different symptoms.

Other symptoms and signs of stroke may include:

- Sudden numbness, paralysis or weakness of the face, arm or leg (especially on one side of the body)

- Trouble speaking and understanding what others are saying. You may experience confusion, slur words or have difficulty understanding speech.

- Sudden loss or blurring of vision in one or both eyes or you may see double

- Dizziness

- Paralysis or numbness of the face, arm or leg. You may develop sudden numbness, weakness or paralysis in the face, arm or leg. This often affects just one side of the body. Try to raise both your arms over your head at the same time. If one arm begins to fall, you may be having a stroke. Also, one side of your mouth may droop when you try to smile.

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding speech

- Difficulty understanding what others are saying

- Problems with balance and co-ordination

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Sudden and very severe headache resulting in a blinding pain unlike anything experienced before, which may be accompanied by vomiting, dizziness or altered consciousness, may indicate that you’re having a stroke.

- Loss of consciousness

However, there may be other causes for these symptoms.

Warning signs in posterior circulation strokes

Posterior circulations strokes (a stroke that occurs in the back part of the brain) occurs when a blood vessel in the back part of the brain is blocked causing the death of brain cells (called an infarction) in the area of the blocked blood vessel. This type of stroke can also be caused by a ruptured blood vessel in the back part of the brain. When this type of stroke happens several symptoms occur and they can be very different than the symptoms that occur in the blood circulation to the front part of the brain (called anterior circulation strokes).

Symptoms of posterior circulation strokes include:

- Vertigo, like the room, is spinning.

- Imbalance

- One-sided arm or leg weakness.

- Slurred speech or dysarthria

- Double vision or other vision problems

- A headache

- Nausea and or vomiting

If someone shows any of these signs and symptoms, immediately call your local emergency medical services number straight away.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

The symptoms of a TIA, also known as a mini-stroke, are the same as a stroke, but tend to only last between a few minutes and a few hours before disappearing completely.

Although the symptoms do improve, a TIA should never be ignored as it’s a serious warning sign of a problem with the blood supply to your brain. It means you’re at an increased risk of having a stroke in the near future.

Complications of a stroke

A stroke can sometimes cause temporary or permanent disabilities, depending on how long the brain lacks blood flow and which part was affected. Complications may include:

- Paralysis or loss of muscle movement. You may become paralyzed on one side of your body, or lose control of certain muscles, such as those on one side of your face or one arm. Physical therapy may help you return to activities hampered by paralysis, such as walking, eating and dressing.

- Difficulty talking or swallowing. A stroke may cause you to have less control over the way the muscles in your mouth and throat move, making it difficult for you to talk clearly (dysarthria), swallow or eat (dysphagia). You also may have difficulty with language (aphasia), including speaking or understanding speech, reading or writing. Therapy with a speech and language pathologist may help.

- Memory loss or thinking difficulties. Many people who have had strokes experience some memory loss. Others may have difficulty thinking, making judgments, reasoning and understanding concepts.

- Emotional problems. People who have had strokes may have more difficulty controlling their emotions, or they may develop depression.

- Pain. People who have had strokes may have pain, numbness or other strange sensations in parts of their bodies affected by stroke. For example, if a stroke causes you to lose feeling in your left arm, you may develop an uncomfortable tingling sensation in that arm. People also may be sensitive to temperature changes, especially extreme cold after a stroke. This complication is known as central stroke pain or central pain syndrome. This condition generally develops several weeks after a stroke, and it may improve over time. But because the pain is caused by a problem in your brain, rather than a physical injury, there are few treatments.

- Changes in behavior and self-care ability. People who have had strokes may become more withdrawn and less social or more impulsive. They may need help with grooming and daily chores.

As with any brain injury, the success of treating these complications will vary from person to person.

CVA causes

A stroke occurs when the blood supply to your brain is interrupted or reduced. This deprives your brain of oxygen and nutrients, which can cause your brain cells to die.

A stroke may be caused by a blocked artery (ischemic stroke) or the leaking or bursting of a blood vessel (hemorrhagic stroke). Some people may experience only a temporary disruption of blood flow to their brain (transient ischemic attack or TIA). This causes what’s known as a mini-stroke, often lasting between a few minutes and several hours. TIA should be treated urgently, as they’re often a warning sign you’re at risk of having a full stroke in the near future. Seek medical advice as soon as possible, even if your symptoms resolve.

There are two main causes of strokes:

- Ischemic stroke – where the blood supply is stopped because of a blood clot causing severely reduced blood flow (ischemia), accounting for 85% of all cases. Blocked or narrowed blood vessels are caused by fatty deposits that build up in blood vessels or by blood clots or other debris that travel through the bloodstream, most often from the heart, and lodge in the blood vessels in the brain.

- Hemorrhagic stroke– where a weakened blood vessel supplying the brain bursts or ruptures. Brain hemorrhages can result from many conditions that affect the blood vessels. Factors related to hemorrhagic stroke include:

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure

- Overtreatment with blood thinners (anticoagulants)

- Bulges at weak spots in your blood vessel walls (aneurysms)

- Trauma (such as a car accident)

- Protein deposits in blood vessel walls that lead to weakness in the vessel wall (cerebral amyloid angiopathy)

- Ischemic stroke leading to hemorrhage

- A less common cause of bleeding in the brain is the rupture of an irregular tangle of thin-walled blood vessels (arteriovenous malformation).

In most cases, a stroke is caused by a blood clot that blocks blood flow to the brain (ischemic stroke). But in some instances, despite testing, the cause can’t be determined. Strokes without a known cause are called cryptogenic stroke. It’s estimated that about 1 in 3 ischemic strokes are cryptogenic. Some studies suggest that the incidence of cryptogenic stroke is higher in African- Americans (two times more likely) and Hispanics (46% more likely).

Possible hidden causes of stroke:

- Irregular heartbeat (atrial fibrillation) – Atrial fibrillation patients are at a 5 times greater risk for stroke.

- Heart structure problem (such as patent foramen ovale)

- Hardening of the arteries (large artery atherosclerosis)

- Blood clotting disorder (thrombophilia)

Risk factors for stroke

Many factors can increase your risk of a stroke. Some factors can also increase your chances of having a heart attack. Potentially treatable stroke risk factors include:

Lifestyle risk factors

- Being overweight or obese

- Physical inactivity. Insufficient physical inactivity and poor diet are associated with increased risk for stroke. Lack of exercise increases the chances of stroke attack in an individual. Insufficient physical activity is also linked to other health issues like high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes, all conditions related to high stroke incidence 24. Poor diet influences the risk of stroke, contributing to hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes. Certain dietary components are well known to heighten risk; for example, excessive salt intake is linked to high hypertension and stroke. Conversely, a diet high in fruit and vegetables (notably, the Mediterranean diet) has been shown to decrease the risk of stroke 25.

- Heavy or binge drinking

- Use of illicit drugs such as cocaine, heroin, phencyclidine (PCP), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), cannabis/marijuana and methamphetamines 26. Illicit drug use is a common predisposing factor for stroke among individuals aged below 35 years. US research showed that the proportion of illicit drug users among stroke patients aged 15–44 years was six times higher than among age-matched patients admitted with other serious conditions 27. However, there is no strong evidence to confirm these findings, and the relationship between these drugs and stroke is anecdotal 28.

Medical risk factors

- Atrial fibrillation (AF): Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an important risk factor for stroke, increasing risk two- to five-fold depending upon the age of the individual concerned 29. Atrial fibrillation (AF) contributes to 15% of all strokes and produces more severe disability and higher mortality than non-AF-related strokes 30. Research has shown that in AF, decreased blood flow in the left atrium causes thrombolysis and embolism in the brain. However, recent studies have contradicted this finding, citing poor evidence of sequential timing of incidence of AF and stroke, and noting that in some patients the occurrence of AF is recorded only after a stroke. In other instances, individuals harboring genetic mutations specific to AF can be affected by stroke long before the onset of AF 31.

- High blood pressure (hypertension) — the risk of stroke begins to increase at blood pressure readings higher than 120/80 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). In one study, a blood pressure of at least 160/90 mmHg and a history of hypertension were considered equally important predispositions for stroke, with 54% of the stroke-affected population having these characteristics 32. Blood pressure and prevalence of stroke are correlated in both hypertensive and normal individuals. A study reported that a 5–6 mm Hg reduction in blood pressure lowered the relative risk of stroke by 42% 33. Randomized trials of interventions to reduce hypertension in people aged 60+ have shown similar results, lowering the incidences of symptoms of stroke by 36% and 42%, respectively 34. Your doctor will help you decide on a target blood pressure based on your age, whether you have diabetes and other factors.

- Cigarette smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke. An average smoker has twice the chance of suffering from a stroke of a non-smoker. Smoking contributes to 15% of stroke-related mortality. Research suggests that an individual who stops smoking reduces the relative risk of stroke, while prolonged second-hand smoking confers a 30% elevation in the risk of stroke 35, 36.

- High cholesterol. Total cholesterol is associated with risk of stroke, whereas high-density lipoprotein (HDL) decreases stroke incidence 37. Therefore, evaluation of lipid profile enables estimation of the risk of stroke. In one study, low levels of HDL (<0.90 mmol/L), high levels of total triglyceride (>2.30 mmol/L) and hypertension were associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of stroke-related death in the population 38.

- Diabetes. Diabetes doubles the risk of ischemic stroke and confers an approximately 20% higher mortality rate. Moreover, the prognosis for diabetic individuals after a stroke is worse than for non-diabetic patients, including higher rates of severe disability and slower recovery 39. Tight regulation of glycemic levels alone is ineffective; medical intervention plus behavioral modifications could help decrease the severity of stroke for diabetic individuals 40.

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) — a sleep disorder in which the oxygen level intermittently drops during the night.

- Cardiovascular disease, including heart failure, heart defects, heart infection or abnormal heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation).

Other factors associated with a higher risk of stroke include:

- Personal or family history of stroke, heart attack or transient ischemic attack.

- Being age 55 or older.

- Race or ethnicity — African-Americans have a higher risk of stroke than do people of other races.

- Gender — Men have a higher risk of stroke than women. Women are usually older when they have strokes, and they’re more likely to die of strokes than are men. Also, they may have some risk from some birth control pills or hormone therapies that include estrogen, as well as from pregnancy and childbirth.

- Hormones — Use of birth control pills or hormone therapies that include estrogen increases risk.

CVA pathophysiology

Atherosclerosis is the most common and important underlying pathology which leads to the formation of an atherothrombotic plaque secondary to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL or “bad” cholesterol) build up in the arteries supplying the brain 41. These plagues may block or decrease the diameter of the neck or intracranial arteries resulting in distal ischemia of the brain. More commonly they may also rupture. Plague rupture leads to exposure of the underlying cholesterol crystals which attract platelets and fibrin. Release of fibrin-platelet rich emboli causes strokes in the distal arterial territories via an artery-to-artery embolic mechanism. The nature of the cardiac source of emboli depends on the underlying cardiac problem. In atrial fibrillation, clots tend to be formed in the left atrium. These are red blood cell rich clots. There may be tumor emboli in left atrial myxoma and bacterial clumps from vegetations when emboli arise during infective endocarditis.

When an arterial blockage occurs, the immediately adjacent neurons lose their supply of oxygen and nutrients. The inability to go through aerobic metabolism and produce ATP causes the Na+/K+ ATPase pumps to fail, leading to an accumulation of Na+ inside the cells and K+ outside the cells. The Na+ ion accumulation leads to cell depolarization and subsequent glutamate release. Glutamate opens NMDA and AMPA receptors and allows for calcium ions to flow into the cells. A continuous flow of calcium leads to continuous neuronal firing and eventual cell death via excitotoxicity 42.

In the first 12 hours, there are no significant macroscopic changes. There is cytotoxic edema related to energy production failure with neuronal cellular swelling. This early infarction state can be visualized by diffusion-weighted MRI which shows restricted diffusion as a result of neuronal cellular swelling. Six to twelve hours after the stroke, vasogenic edema develops. This phase may be best visualized with FLAIR sequence MRI. Both cytotoxic and vasogenic edema causes swelling of the infarcted area and increases in intracranial pressure. These are followed by the invasion of phagocytic cells which try to clear away the dead cells. Extensive phagocytosis causes softening and liquefaction of the affected brain tissues, with peak liquefaction occurring 6 months post-stroke. Several months after a stroke, astrocytes form a dense network of glial fibers mixed with capillaries and connective tissue 43.

Hemorrhagic strokes lead to a similar type of cellular dysfunction and concerted events of repair with the addition of blood extravasation and resorption 44.

CVA prevention

Knowing your stroke risk factors, following your doctor’s recommendations and adopting a healthy lifestyle are the best steps you can take to prevent a stroke. If you’ve had a stroke or a transient ischemic attack (TIA), these measures may help you avoid having another stroke. The follow-up care you receive in the hospital and afterward may play a role as well.

Many stroke prevention strategies are the same as strategies to prevent heart disease. In general, healthy lifestyle recommendations include:

- Controlling high blood pressure (hypertension). One of the most important things you can do to reduce your stroke risk is to keep your blood pressure under control. If you’ve had a stroke, lowering your blood pressure can help prevent a subsequent transient ischemic attack or stroke.

Exercising, managing stress, maintaining a healthy weight, and limiting the amount of sodium and alcohol you eat and drink are all ways to keep high blood pressure in check.. In addition to recommending lifestyle changes, your doctor may prescribe medications to treat high blood pressure.

- Lowering the amount of cholesterol and saturated fat in your diet. Eating less cholesterol and fat, especially saturated fat and trans fats, may reduce the fatty deposits (plaques) in your arteries. If you can’t control your cholesterol through dietary changes alone, your doctor may prescribe a cholesterol-lowering medication.

- Quitting smoking. Smoking raises the risk of stroke for smokers and nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke. Quitting tobacco use reduces your risk of stroke.

- Controlling diabetes. You can manage diabetes with diet, exercise, weight control and medication.

- Maintaining a healthy weight. Being overweight contributes to other stroke risk factors, such as high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Weight loss of as little as 10 pounds may lower your blood pressure and improve your cholesterol levels.

- Eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables. A diet containing five or more daily servings of fruits or vegetables may reduce your risk of stroke. Following the Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes olive oil, fruit, nuts, vegetables and whole grains, may be helpful.

- Exercising regularly. Aerobic or “cardio” exercise reduces your risk of stroke in many ways. Exercise can lower your blood pressure, increase your level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and improve the overall health of your blood vessels and heart. It also helps you lose weight, control diabetes and reduce stress. Gradually work up to 30 minutes of activity — such as walking, jogging, swimming or bicycling — on most, if not all, days of the week.

- Drinking alcohol in moderation, if at all. Alcohol can be both a risk factor and a protective measure for stroke. Heavy alcohol consumption increases your risk of high blood pressure, ischemic strokes and hemorrhagic strokes. However, drinking small to moderate amounts of alcohol, such as one drink a day, may help prevent ischemic stroke and decrease your blood’s clotting tendency. Alcohol may also interact with other drugs you’re taking. Talk to your doctor about what’s appropriate for you.

- Treating obstructive sleep apnea, if present. Your doctor may recommend an overnight oxygen assessment to screen for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). If obstructive sleep apnea is detected, it may be treated by giving you oxygen at night or having you wear a small device in your mouth.

- Avoiding illicit drugs. Certain street drugs, such as cocaine and methamphetamines, are established risk factors for a TIA or a stroke. Cocaine reduces blood flow and can cause narrowing of arteries.

Preventive medications

If you’ve had an ischemic stroke or TIA, your doctor may recommend medications to help reduce your risk of having another stroke. These include:

- Anti-platelet drugs. Platelets are cells in your blood that initiate clots. Anti-platelet drugs make these cells less sticky and less likely to clot. The most commonly used anti-platelet medication is aspirin. Your doctor can help you determine the right dose of aspirin for you. Your doctor may also consider prescribing Aggrenox, a combination of low-dose aspirin and the anti-platelet drug dipyridamole, to reduce the risk of blood clotting. If aspirin doesn’t prevent your TIA or stroke, or if you can’t take aspirin, your doctor may instead prescribe an anti-platelet drug such as clopidogrel (Plavix).

- Anticoagulants. These drugs, which include heparin and warfarin (Coumadin), reduce blood clotting. Heparin is fast-acting and may be used over a short period of time in the hospital. Slower acting warfarin may be used over a longer term. Warfarin is a powerful blood-thinning drug, so you’ll need to take it exactly as directed and watch for side effects. Your doctor may prescribe these drugs if you have certain blood-clotting disorders, certain arterial abnormalities, an abnormal heart rhythm or other heart problems. Other newer blood thinners may be used if your TIA or stroke was caused by an abnormal heart rhythm.

CVA diagnosis

To determine the most appropriate treatment for your stroke, your emergency team needs to evaluate the type of stroke you’re having and the areas of your brain affected by the stroke. They also need to rule out other possible causes of your symptoms, such as a brain tumor or a drug reaction. Your doctor may use several tests to determine your risk of stroke, including:

- Physical examination. Your doctor will ask you or a family member what symptoms you’ve been having, when they started and what you were doing when they began. Your doctor then will evaluate whether these symptoms are still present. Your doctor will want to know what medications you take and whether you have experienced any head injuries. You’ll be asked about your personal and family history of heart disease, transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke.

Your doctor will check your blood pressure and use a stethoscope to listen to your heart and to listen for a whooshing sound (bruit) over your neck (carotid) arteries, which may indicate atherosclerosis. Your doctor may also use an ophthalmoscope to check for signs of tiny cholesterol crystals or clots in the blood vessels at the back of your eyes.

- Blood tests. You may have several blood tests, which tell your care team how fast your blood clots, whether your blood sugar is abnormally high or low, whether critical blood chemicals are out of balance, or whether you may have an infection. Managing your blood’s clotting time and levels of sugar and other key chemicals will be part of your stroke care.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. A CT scan uses a series of X-rays to create a detailed image of your brain. A CT scan can show a hemorrhage, tumor, stroke and other conditions. Doctors may inject a dye into your bloodstream to view your blood vessels in your neck and brain in greater detail (computerized tomography angiography or CTA).

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses powerful radio waves and magnets to create a detailed view of your brain. An MRI can detect brain tissue damaged by an ischemic stroke and brain hemorrhages. Your doctor may inject a dye into a blood vessel to view the arteries and veins and highlight blood flow (magnetic resonance angiography [MRA] or magnetic resonance venography [MRV]).

- Carotid ultrasound. In this test, sound waves create detailed images of the inside of the carotid arteries in your neck. This test shows buildup of fatty deposits (plaques) and blood flow in your carotid arteries.

- Cerebral angiogram. In this test, your doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube (catheter) through a small incision, usually in your groin, and guides it through your major arteries and into your carotid or vertebral artery. Then your doctor injects a dye into your blood vessels to make them visible under X-ray imaging. This procedure gives a detailed view of arteries in your brain and neck.

- Echocardiogram. An echocardiogram uses sound waves to create detailed images of your heart. An echocardiogram can find a source of clots in your heart that may have traveled from your heart to your brain and caused your stroke. You may have a transesophageal echocardiogram. In this test, your doctor inserts a flexible tube with a small device (transducer) attached into your throat and down into the tube that connects the back of your mouth to your stomach (esophagus). Because your esophagus is directly behind your heart, a transesophageal echocardiogram can create clear, detailed ultrasound images of your heart and any blood clots.

CVA treatment

Emergency treatment for stroke depends on whether you’re having an ischemic stroke blocking an artery — the most common kind — or a hemorrhagic stroke that involves bleeding into the brain.

Ischemic stroke treatment

To treat an ischemic stroke, doctors must quickly restore blood flow to your brain.

Emergency treatment with medications

Therapy with drugs that can break up a clot has to be given within 4.5 hours from when symptoms first started if given intravenously. The sooner these drugs are given, the better. Quick treatment not only improves your chances of survival but also may reduce complications. You may be given:

- Aspirin. Aspirin is an immediate treatment given in the emergency room to reduce the likelihood of having another stroke. Aspirin prevents blood clots from forming. A Cochrane review concluded that aspirin given within 48 hours of symptom onset for ischemic strokes prevented the recurrence of ischemic strokes and improved long-term outcomes. There was no major risk of early intracranial hemorrhage with aspirin 45. The usage of aspirin as monotherapy or dual therapy along with clopidogrel within 24 – 48 hours after the onset of symptoms significantly improved patient outcomes 46.

- Intravenous injection of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the gold standard treatment for ischemic stroke. An IV injection of a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (TPA), also called alteplase (Activase) or tenecteplase (TNKase). An injection of TPA is usually given through a vein in the arm. This potent clot-busting drug needs to be given within 3 to 4.5 hours after stroke symptoms begin if it’s given in the vein. Tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) restores blood flow by dissolving the blood clot causing your stroke, and it may help people who have had strokes recover more fully. Your doctor will consider certain risks, such as potential bleeding in the brain, to determine if TPA is appropriate for you. According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the contraindications to intravenous thrombolysis include active internal bleeding, recent intracranial surgery or serious head trauma, intracranial conditions that may increase the risk of bleeding, bleeding diathesis, severe uncontrolled hypertension, current intracranial hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and a history of a recent stroke.

- Inclusion criteria for TPA 47:

- Clinical diagnosis of ischemic stroke

- <4.5 hours of the onset of symptoms

- Age >18 and <80 years

- Symptoms of stroke presenting for more than 30 minutes

- Excision criteria for TPA 48:

- Unknown timeline of onset of patient symptoms

- Intracranial hemorrhage or any active bleeding

- Persistently elevated blood pressure ≥ 185 mmHg systolic and ≥ 110 mmHg diastolic

- Low platelets <100,000/mm3, altered INR >1.7, PT >15 sec or aPTT >40sec

- Current use of anti-coagulant

- Severe hypoglycemia <50mg/dL

- History of previous intracranial hemorrhage

- History of gastrointestinal bleeding in the past 21 days

- History of intracranial or intraspinal surgery in the past 90 days

- History of intra-axial intracranial neoplasm or gastrointestinal malignancy

- Inclusion criteria for TPA 47:

Emergency procedures

Doctors sometimes treat ischemic strokes with procedures inside the blocked blood vessel (also called endovascular therapy or endovascular procedure) that must be performed as soon as possible, depending on features of the blood clot:

- Medications delivered directly to the brain. Doctors may insert a long, thin tube (catheter) through an artery in your groin and thread it to your brain to deliver tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) directly into the area where the stroke is occurring. The time window for this treatment is somewhat longer than for intravenous TPA but is still limited.

- Mechanical clot removal (mechanical thrombectomy). Doctors may use a device attached to a catheter into your brain to physically break up or grab and remove the clot. This procedure is particularly beneficial for people with large clots that can’t be completely dissolved with TPA. This procedure is often performed in combination with injected TPA.

The time window when these procedures can be considered has been expanding due to newer imaging technology. Doctors may order perfusion imaging tests (done with CT or MRI) to help determine how likely it is that someone can benefit from endovascular therapy.

Multiple stroke trials in 2015 showed that endovascular thrombectomy (mechanical clot removal) in the first six hours is much better than standard medical care in patients with large vessel occlusion in the arteries of the proximal anterior circulation. These benefits sustained irrespective of geographical location and patient characteristics 41.

Again in 2018, a significant paradigm shift happened in stroke care. DAWN trial showed significant benefits of endovascular thrombectomy in patients with large vessel occlusion in the arteries of the proximal anterior circulation 49. This trial extended the stroke window up to 24 hours in selected patients using perfusion imaging. Subsequently, now more patients can be treated, even up to 24 hours 49.

The current recommendation in selected patients with large vessel occlusion with acute ischemic stroke in the anterior circulation and who also meet other DAWN and DEFUSE 3 criteria, mechanical thrombectomy is recommended within the time frame of 6 to 16 hours of last known normal. In selected patients who meet the DAWN criteria, mechanical thrombectomy is reasonable within 24 hours of last known normal 50, 49.

Other procedures to decrease your risk of having another stroke

To decrease your risk of having another stroke or transient ischemic attack, your doctor may recommend a procedure to open up an artery that’s narrowed by fatty deposits (plaques). Doctors sometimes recommend the following procedures to prevent a stroke.

Options will vary depending on your situation:

- Carotid endarterectomy. In a carotid endarterectomy, a surgeon removes plaques from arteries that run along each side of your neck to your brain (carotid arteries). In this procedure, your surgeon makes an incision along the front of your neck, opens your carotid artery and removes plaques that block the carotid artery. Your surgeon then repairs the carotid artery with stitches or a patch made from a vein or artificial material (graft). The procedure may reduce your risk of ischemic stroke. However, a carotid endarterectomy also involves risks, especially for people with heart disease or other medical conditions.

- Angioplasty and stents. In an angioplasty, a surgeon gains access to your carotid arteries most often through an artery in your groin. Here, he or she can gently and safely navigate to the carotid arteries in your neck. A balloon is then used to expand the narrowed artery. Then a stent can be inserted to support the opened artery.

Hemorrhagic stroke treatment

Emergency treatment of hemorrhagic stroke focuses on controlling your bleeding and reducing pressure in your brain. Surgery also may be performed to help reduce future risk.

Emergency measures

If you take warfarin (Coumadin) or anti-platelet drugs such as clopidogrel (Plavix) to prevent blood clots, you may be given drugs or transfusions of blood products to counteract the blood thinners’ effects. You may also be given drugs to lower pressure in your brain (intracranial pressure), lower your blood pressure, prevent vasospasm or prevent seizures.

Once the bleeding in your brain stops, treatment usually involves supportive medical care while your body absorbs the blood. Healing is similar to what happens while a bad bruise goes away. If the area of bleeding is large, your doctor may perform surgery to remove the blood and relieve pressure on your brain.

Surgical blood vessel repair

Surgery may be used to repair blood vessel abnormalities associated with hemorrhagic strokes. Your doctor may recommend one of these procedures after a stroke or if an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or other type of vascular malformation caused your hemorrhagic stroke:

- Surgical clipping. A surgeon places a tiny clamp at the base of the aneurysm, to stop blood flow to it. This clamp can keep the aneurysm from bursting, or it can prevent re-bleeding of an aneurysm that has recently hemorrhaged.

- Coiling (endovascular embolization). In this procedure, a surgeon inserts a catheter into an artery in your groin and guides it to your brain using X-ray imaging. Your surgeon then guides tiny detachable coils into the aneurysm (aneurysm coiling). The coils fill the aneurysm, which blocks blood flow into the aneurysm and causes the blood to clot.

- Surgical arteriovenous malformation (AVM) removal. Surgeons may remove a smaller AVM if it’s located in an accessible area of your brain, to eliminate the risk of rupture and lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. However, it’s not always possible to remove an AVM if its removal would cause too large a reduction in brain function, or if it’s large or located deep within your brain.

- Intracranial bypass. In some unique circumstances, surgical bypass of intracranial blood vessels may be an option to treat poor blood flow to a region of the brain or complex vascular lesions, such as aneurysm repair.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery. Using multiple beams of highly focused radiation, stereotactic radiosurgery is an advanced minimally invasive treatment used to repair blood vessel malformations.

Stroke prognosis

The prognosis of stroke is highly dependent on the severity of the stroke, cause of stroke, involved structures, the area involved, time of identification and diagnosis, time of initiating treatment, length and intensity of physical and occupational therapy, and baseline functioning, age, associated risk factors and co-morbidities 51, 52. Patients with significant neurological deficits have a worse prognosis 1.

Early diagnosis and management have a lower chance of permanent morbidity. Untreated acute basilar artery occlusion has extremely high mortality approaching 90%. For those patients who receive adequate treatment, the one-year survival rate is between 60 to 80%. The risk of stroke recurrence is 10 to 15%; hence regular follow up is advised.

Stroke recovery

Following emergency treatment, stroke care focuses on helping you regain your strength, recover as much function as possible and return to independent living. The impact of your stroke depends on the area of the brain involved and the amount of tissue damaged.

If your stroke affected the right side of your brain, your movement and sensation on the left side of your body may be affected. If your stroke damaged the brain tissue on the left side of your brain, your movement and sensation on the right side of your body may be affected. Brain damage to the left side of your brain may cause speech and language disorders.

In addition, if you’ve had a stroke, you may have problems with breathing, swallowing, balancing and vision.

People who survive a stroke are often left with long-term problems caused by injury to their brain.

Some people need a long period of rehabilitation before they can recover their former independence, while many never fully recover and need support adjusting to living with the effects of their stroke.

Most stroke survivors receive treatment in a rehabilitation program. Your doctor will recommend the most rigorous therapy program you can handle based on your age, overall health and your degree of disability from your stroke. Your doctor will take into consideration your lifestyle, interests and priorities, and the availability of family members or other caregivers.

Your rehabilitation program may begin before you leave the hospital. It may continue in a rehabilitation unit of the same hospital, another rehabilitation unit or skilled nursing facility, an outpatient unit, or your home.

Every person’s stroke recovery is different. Depending on your condition, your treatment team may include:

- Doctor trained in brain conditions (neurologist)

- Rehabilitation doctor (physiatrist)

- Nurse

- Dietitian

- Physical therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Recreational therapist

- Speech therapist

- Social worker

- Case manager

- Psychologist or psychiatrist

- Chaplain

Psychological impact

Two of the most common psychological problems that can affect people after a stroke are:

- Depression – many people experience intense bouts of crying, and feel hopeless and withdrawn from social activities

- Anxiety – where people experience general feelings of fear and anxiety, sometimes punctuated by intense, uncontrolled feelings of anxiety (anxiety attacks)

Feelings of anger, frustration and bewilderment are also common.

You’ll receive a psychological assessment from a member of your healthcare team soon after your stroke to check if you’re experiencing any emotional problems.

Advice should be given to help deal with the psychological impact of stroke. This includes the impact on relationships with other family members and any sexual relationship.

There should also be a regular review of any problems of depression and anxiety, and psychological and emotional symptoms generally.

These problems may settle down over time, but if they are severe or last a long time, doctors can refer people for expert healthcare from a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist.

For some people, medicines and psychological therapies, such as counselling or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), can help. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a therapy that aims to change the way you think about things to produce a more positive state of mind.

Cognitive impact

Cognitive is a term used by scientists to refer to the many processes and functions our brain uses to process information.

One or more cognitive functions can be disrupted by a stroke, including:

- Communication – both verbal and written

- Spatial awareness – having a natural awareness of where your body is in relation to your immediate environment

- Memory

- Concentration

- Executive function – the ability to plan, solve problems and reason about situations

- Praxis – the ability to carry out skilled physical activities, such as getting dressed or making a cup of tea

As part of your treatment, each one of your cognitive functions will be assessed and a treatment and rehabilitation plan will be created.

You can be taught a wide range of techniques that can help you relearn disrupted cognitive functions, such as recovering your communication skills through speech and language therapy.

There are many ways to compensate for any loss of cognitive function, such as using memory aids, diaries and routines to help plan daily tasks.

Most cognitive functions will return after time and rehabilitation, but you may find they don’t return to the way they were before.

The damage a stroke causes to your brain also increases the risk of developing vascular dementia. This may happen immediately after a stroke or may develop some time after the stroke occurred.

Movement problems

Strokes can cause weakness or paralysis on one side of the body, and can result in problems with co-ordination and balance.

Many people also experience extreme tiredness (fatigue) in the first few weeks after a stroke, and may also have difficulty sleeping, making them even more tired.

As part of your rehabilitation, you should be seen by a physiotherapist, who will assess the extent of any physical disability before drawing up a treatment plan.

Physiotherapy will often involve several sessions a week, focusing on areas such as exercises to improve your muscle strength and overcome any walking difficulties.

The physiotherapist will work with you by setting goals. At first, these may be simple goals, such as picking up an object. As your condition improves, more demanding long-term goals, such as standing or walking, will be set.

A careworker or carer, such as a member of your family, will be encouraged to become involved in your physiotherapy. The physiotherapist can teach you both simple exercises you can carry out at home.

If you have problems with movement and certain activities, such as getting washed and dressed, you may also receive help from an occupational therapist. They can find ways to manage any difficulties.

Occupational therapy may involve adapting your home or using equipment to make everyday activities easier, and finding alternative ways of carrying out tasks you have problems with.

Communication problems

After having a stroke, many people experience problems with speaking and understanding, as well as reading and writing.

If the parts of the brain responsible for language are damaged, this is called aphasia, or dysphasia. If there is weakness in the muscles involved in speech as a result of brain damage, this is known as dysarthria.

You should see a speech and language therapist as soon as possible for an assessment and to start therapy to help you with your communication.

This may involve:

- exercises to improve your control over your speech muscles

- using communication aids – such as letter charts and electronic aids

- using alternative methods of communication – such as gestures or writing

Swallowing problems

The damage caused by a stroke can interrupt your normal swallowing reflex, making it possible for small particles of food to enter your windpipe.

Problems with swallowing are known as dysphagia. Dysphagia can lead to damage to your lungs, which can trigger a lung infection (pneumonia).

You may need to be fed using a feeding tube during the initial phases of your recovery to prevent any complications from dysphagia.

The tube is usually put into your nose and passed into your stomach (nasogastric tube), or it may be directly connected to your stomach in a minor surgical procedure carried out using local anesthetic (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, or PEG).

In the long term, you’ll usually see a speech and language therapist several times a week for treatment to manage your swallowing problems.

Treatment may involve tips to make swallowing easier, such as taking smaller bites of food and advice on posture, and exercises to improve control of the muscles involved in swallowing.

Visual problems

Stroke can sometimes damage the parts of the brain that receive, process and interpret information sent by the eyes.

This can result in losing half the field of vision – for example, only being able to see the left- or right hand side of what’s in front of you.

Strokes can also affect the control of the movement of the eye muscles. This can cause double vision.

If you have any problems with your vision after a stroke, you’ll be referred to an eye specialist called an orthoptist, who can assess your vision and suggest possible treatments.

For example, if you’ve lost part of your field of vision, you may be offered eye movement therapy. This involves exercises to help you look to the side with the reduced vision.

You may also be given advice about particular ways to perform tasks that can be difficult if your vision is reduced on one side, such as getting dressed.

Bladder and bowel control

Some strokes damage the part of the brain that controls bladder and bowel movements. This can result in urinary incontinence and difficulty with bowel control.

Some people may regain bladder and bowel control quite quickly, but if you still have problems after leaving hospital, help is available from the hospital, your GP, and specialist continence advisers.

Don’t be embarrassed – seek advice if you have a problem, as there are lots of treatments that can help.

These include:

- bladder retraining exercises

- medications

- pelvic floor exercises

- using incontinence products

Sex after a stroke

Having sex won’t put you at higher risk of having a stroke. There’s no guarantee you won’t have another stroke, but there’s no reason why it should happen while you’re having sex.

Even if you’ve been left with a severe disability, you can experiment with different positions and find new ways of being intimate with your partner.

Be aware that some medications can reduce your sex drive (libido), so make sure your doctor knows if you have a problem – there may be other medicines that can help.

Some men may experience erectile dysfunction after having a stroke. Speak to your GP or rehabilitation team if this is the case, as there are a number of treatments available that can help.

Driving after a stroke

If you’ve had a stroke or TIA, you can’t drive for one month. Whether you can return to driving depends on what long-term disabilities you may have and the type of vehicle you drive.

It’s often not physical problems that can make driving dangerous, but problems with concentration, vision, reaction time and awareness that can develop after a stroke.

Your doctor can advise you on whether you can start driving again a month after your stroke, or whether you need further assessment at a mobility center.

Preventing further strokes

If you’ve had a stroke, your chances of having another one are significantly increased.

You’ll usually require long-term treatment with medications aimed at improving the underlying risk factors for your stroke.

For example:

- medication – to help lower your blood pressure

- anticoagulants or antiplatelets – to reduce your risk of blood clots

- statins – to lower your cholesterol levels

You’ll also be encouraged to make lifestyle changes to improve your general health and lower your stroke risk, such as:

- eating a healthy diet

- exercising regularly

- stopping smoking if you smoke

- cutting down on the amount of alcohol you drink

Caring for someone who’s had a stroke

There are many ways you can provide support to a friend or relative who’s had a stroke to speed up their rehabilitation process.

These include:

- helping them practise physiotherapy exercises in between their sessions with the physiotherapist

- providing emotional support and reassurance their condition will improve with time

- helping motivate them to reach their long-term goals

- adapting to any needs they may have, such as speaking slowly if they have communication problems

Caring for somebody after a stroke can be a frustrating and lonely experience. The advice outlined below may help.

Be prepared for changed behavior

Someone who’s had a stroke can often seem as though they’ve had a change in personality and appear to act irrationally at times. This is the result of the psychological and cognitive impact of a stroke.

They may become angry or resentful towards you. Upsetting as it may be, try not to take it personally.

It’s important to remember they’ll often start to return to their old self as their rehabilitation and recovery progresses.

Try to remain patient and positive

Rehabilitation can be a slow and frustrating process, and there will be periods of time when it appears little progress has been made.

Encouraging and praising any progress, no matter how small it may appear, can help motivate someone who’s had a stroke to achieve their long-term goals.

Make time for yourself

If you’re caring for someone who’s had a stroke, it’s important not to neglect your own physical and psychological wellbeing. Socializing with friends or pursuing leisure interests will help you cope better with the situation.

Ask for help

There are a wide range of support services and resources available for people recovering from strokes, and their families and carers. This ranges from equipment that can help with mobility, to psychological support for carers and families.

The hospital staff involved with the rehabilitation process can provide advice and relevant contact information.

References- Gowda SN, De Jesus O. Brainstem Infarction. [Updated 2022 Feb 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560896

- Brain Stem Stroke. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/types-of-stroke/brain-stem-stroke

- Kameda W, Kawanami T, Kurita K, Daimon M, Kayama T, Hosoya T, Kato T; Study Group of the Association of Cerebrovascular Disease in Tohoku. Lateral and medial medullary infarction: a comparative analysis of 214 patients. Stroke. 2004 Mar;35(3):694-9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117570.41153.35

- Burger KM, Tuhrim S, Naidich TP. Brainstem vascular stroke anatomy. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2005 May;15(2):297-324, x. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.05.005

- Ortiz de Mendivil A, Alcalá-Galiano A, Ochoa M, Salvador E, Millán JM. Brainstem stroke: anatomy, clinical and radiological findings. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2013 Apr;34(2):131-41. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2013.01.004

- Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G, Regli F. The Lausanne Stroke Registry: analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients with first stroke. Stroke. 1988 Sep;19(9):1083-92. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.9.1083

- Guzik A, Bushnell C. Stroke Epidemiology and Risk Factor Management. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2017 Feb;23(1, Cerebrovascular Disease):15-39. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000416

- Norrving B, Cronqvist S. Lateral medullary infarction: prognosis in an unselected series. Neurology. 1991 Feb;41(2 ( Pt 1

- Balami JS, Chen RL, Buchan AM. Stroke syndromes and clinical management. QJM. 2013 Jul;106(7):607-15. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct057

- Wall M, Wray SH. The one-and-a-half syndrome–a unilateral disorder of the pontine tegmentum: a study of 20 cases and review of the literature. Neurology. 1983 Aug;33(8):971-80. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.8.971

- Liu GT, Crenner CW, Logigian EL, Charness ME, Samuels MA. Midbrain syndromes of Benedikt, Claude, and Nothnagel: setting the record straight. Neurology. 1992 Sep;42(9):1820-2. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1820

- Marx JJ, Thömke F. Classical crossed brain stem syndromes: myth or reality? J Neurol. 2009 Jun;256(6):898-903. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5037-2

- Moncayo J. Midbrain infarcts and hemorrhages. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2012;30:158-61. doi: 10.1159/000333630

- Tacik P, Krasnianski M, Alfieri A, Dressler D. Brissaud-Sicard syndrome caused by a diffuse brainstem glioma. A rare differential diagnosis of hemifacial spasm. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014 Feb;156(2):429-30. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1984-6

- Stalcup ST, Tuan AS, Hesselink JR. Intracranial causes of ophthalmoplegia: the visual reflex pathways. Radiographics. 2013 Sep-Oct;33(5):E153-69. doi: 10.1148/rg.335125142

- Tacik P, Alfieri A, Kornhuber M, Dressler D. Gasperini’s syndrome: its neuroanatomical basis now and then. J Hist Neurosci. 2012 Jan;21(1):17-30. doi: 10.1080/0964704X.2011.568045

- Hubloue I, Laureys S, Michotte A. A rare case of diplopia: medial inferior pontine syndrome or Foville’s syndrome. Eur J Emerg Med. 1996 Sep;3(3):194-8. doi: 10.1097/00063110-199609000-00011

- Zaorsky, N. G., & Luo, J. J. (2012). A case of classic raymond syndrome. Case reports in neurological medicine, 2012, 583123. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/583123

- Krasnianski M, Neudecker S, Schlüter A, Zierz S. Avellis-Syndrom bei Hirnstammischämien [Avellis’ syndrome in brainstem infarctions]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2003 Dec;71(12):650-3. German. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45345

- Krasnianski M, Müller T, Stock K, Zierz S. Between Wallenberg syndrome and hemimedullary lesion: Cestan-Chenais and Babinski-Nageotte syndromes in medullary infarctions. J Neurol. 2006 Nov;253(11):1442-6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0231-3

- Krasnianski M, Winterholler M, Neudecker S, Zierz S. Klassische alternierende Medulla-oblongata-Syndrome – Eine historisch-kritische und topodiagnostische Analyse – [Classical crossed syndromes of the medulla oblongata. A historical and topodiagnostic discussion]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2003 Aug;71(8):397-405. German. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41192

- Pergami P, Poloni TE, Imbesi F, Ceroni M, Simonetti F. Dejerine’s syndrome or Spiller’s syndrome? Neurol Sci. 2001 Aug;22(4):333-6. doi: 10.1007/s10072-001-8178-3

- Lui F, Tadi P, Anilkumar AC. Wallenberg Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Sep 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470174

- Zhou ML, Zhu L, Wang J, Hang CH, Shi JX. The inflammation in the gut after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Surg Res. 2007 Jan;137(1):103-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.06.023

- Estruch R, Ros E, Martínez-González MA. Mediterranean diet for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369(7):676-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1306659

- Esse, K., Fossati-Bellani, M., Traylor, A., & Martin-Schild, S. (2011). Epidemic of illicit drug use, mechanisms of action/addiction and stroke as a health hazard. Brain and behavior, 1(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.7

- Kaku DA, Lowenstein DH. Emergence of recreational drug abuse as a major risk factor for stroke in young adults. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Dec 1;113(11):821-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-821

- Brust JC. Neurologic complications of substance abuse. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Oct 1;31 Suppl 2:S29-34. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200210012-00002

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991 Aug;22(8):983-8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983

- Romero, J. R., Morris, J., & Pikula, A. (2008). Stroke prevention: modifying risk factors. Therapeutic advances in cardiovascular disease, 2(4), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753944708093847