What is demyelination

Demyelination describes a loss of myelin with relative preservation of axons. Demyelination results from diseases that damage myelin sheaths or the cells that form them. Demyelination diseases should be distinguished from those in which there is a failure to form myelin normally (sometimes described as dysmyelination). Although axons that have been demyelinated tend to atrophy and may eventually degenerate, demyelinating diseases exclude those in which axonal degeneration occurs first and degradation of myelin is secondary.

Demyelination may be primary of secondary. In primary demyelination, the axon is usually intact and may be preserved, especially if the myelin sheath is exclusively assaulted by the immune system with resulting phagocytosis (primary demyelination). In contrast, secondary demyelination is a common sequel to axonal injury and loss, such that axonopathy and demyelination often coexist as a result of axonal injury from classic axonopathic compounds such as organophosphate agents and acrylamide. In addition to demyelination resulting from multiple sclerosis in humans and the experimentally induced autoimmune encephalopathy of laboratory animals, rarely human immune-mediated demyelinating neuropathies occur during initial or maintenance treatment with immunomodulatory, immunosuppressive, or antineoplastic agents.

Demyelination causes

Primary demyelinating disorders include:

- Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS)

- first symptomatic episode which may or may not progress to MS

- Multiple sclerosis (MS)

- can only be diagnosed if the McDonald diagnostic criteria (or accepted alternative) are met

- variants include

- tumefactive multiple sclerosis

- acute malignant Marburg type

- neuromyelitis optica (Devic disease)

- Schilder type (diffuse cerebral sclerosis)

- Balo concentric sclerosis (BCS)

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

- monophasic usually post viral acute demyelination

- often considered a secondary form of demyelination

- Transverse myelitis

- Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP)

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

Infective demyelinating diseases

- progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)

- HIV encephalitis / HIV dementia complex / HIV associated myelopathy

- progressive rubella panencephalitis

In most cases, toxic and metabolic disease which affect the white matter are considered separately but for the sake of completeness, they are listed below.

Toxic demyelinating disorders

- osmotic demyelination syndrome

- posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)

- chemotherapy

Metabolic/genetic demyelinating diseases

- leukodystrophies

- adrenoleukodystrophy

- Krabbe leukodystrophy

- metachromatic leukodystrophy

- sometimes classified as leukodystrohpies 1

- Alexander disease

- Canavan disease

- Cockayne syndrome

- Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease

Ischemic demyelination

Although not referred to as demyelination many processes which cause ischemia lead to demyelination:

- deep white matter ischemia

- radiotherapy changes

Demyelinating disorders are a subgroup of white matter disorders characterized by the destruction or damage of normally myelinated structures. These disorders may be inflammatory, infective, ischemic or toxic in origin and include 2:

- autoimmune demyelination

- multiple sclerosis (MS)

- Marburg variant of multiple sclerosis

- Schilder type multiple sclerosis

- concentric sclerosis of Balo

- tumefactive demyelinating lesion

- neuromyelitis optica (NMO)

- acute disseminated encephalomyeltitis (ADEM)

- anti-MOG associated encephalomyelitis

- acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (Weston Hurst syndrome)

- multiple sclerosis (MS)

- viral demyelination

- progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML)

- HIV related white matter changes

- HIV encephalitis

- subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE)

- toxic or metabolic demyelination

- osmotic demyelination syndrome

- toxic leukoencephalopathy

- chasing the dragon

- vascular (small-vessel disease) demyelination

- arteriolosclerosis:

- small vessel cerebral ischemia

- chronic hypertensive encephalopathy

- cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- inherited vasculopathies:

- CADASIL

- MELAS

- Fabry disease

- inflammatory vasculitides:

- SLE

- Sjogren syndrome

- Susac syndrome

- primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS)

- venous collagenosis

- others:

- radiotherapy changes

- Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy

- arteriolosclerosis:

- mechanical demyelination due to compression

- trigeminal neuralgia

Multiple sclerosis demyelination

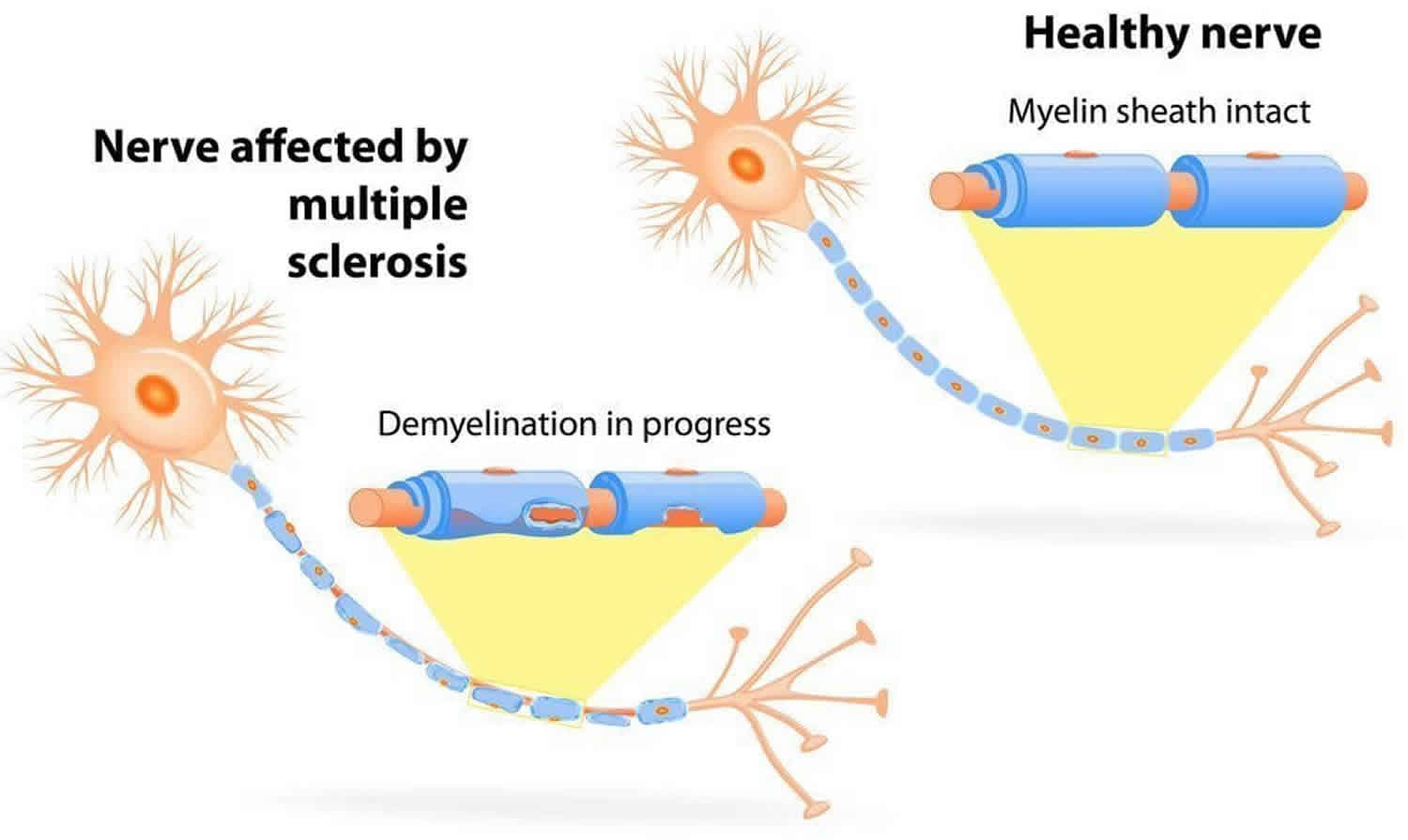

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neuroinflammatory disease that affects myelin, a substance that makes up the membrane (called the myelin sheath) that wraps around nerve fibers (axons). Myelinated axons are commonly called white matter. Researchers have learned that multiple sclerosis also damages the nerve cell bodies, which are found in the brain’s gray matter, as well as the axons themselves in the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve (the nerve that transmits visual information from the eye to the brain). As multiple sclerosis (MS) disease progresses, the brain’s cortex shrinks (cortical atrophy).

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is the most common disabling neurological disease of young adults. It most often appears when people are between 20 to 40 years old. However, it can also affect children and older people.

The term multiple sclerosis refers to the distinctive areas of scar tissue (sclerosis or plaques) that are visible in the white matter of people who have MS. Plaques can be as small as a pinhead or as large as the size of a golf ball. Doctors can see these areas by examining the brain and spinal cord using a type of brain scan called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

While multiple sclerosis (MS) sometimes causes severe disability, it is only rarely fatal and most people with MS have a normal life expectancy.

The course of multiple sclerosis (MS) is unpredictable. A small number of those with MS will have a mild course with little to no disability, while another smaller group will have a steadily worsening disease that leads to increased disability over time. Most people with MS, however, will have short periods of symptoms followed by long stretches of relative relief, with partial or full recovery. There is no way to predict, at the beginning, how an individual person’s disease will progress.

Plaques, or lesions, are the result of an inflammatory process in the brain that causes immune system cells to attack myelin. The myelin sheath helps to speed nerve impulses traveling within the nervous system. Axons are also damaged in MS, although not as extensively, or as early in the disease, as myelin.

Under normal circumstances, cells of the immune system travel in and out of the brain patrolling for infectious agents (viruses, for example) or unhealthy cells. This is called the “surveillance” function of the immune system.

Surveillance cells usually won’t spring into action unless they recognize an infectious agent or unhealthy cells. When they do, they produce substances to stop the infectious agent. If they encounter unhealthy cells, they either kill them directly or clean out the dying area and produce substances that promote healing and repair among the cells that are left.

Researchers have observed that immune cells behave differently in the brains of people with MS. They become active and attack what appears to be healthy myelin. It is unclear what triggers this attack. MS is one of many autoimmunedisorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks a person’s healthy tissue as opposed to performing its normal role of attacking foreign invaders like viruses and bacteria. Whatever the reason, during these periods of immune system activity, most of the myelin within the affected area is damaged or destroyed. The axons also may be damaged. The symptoms of MS depend on the severity of the immune reaction as well as the location and extent of the plaques, which primarily appear in the brain stem, cerebellum, spinal cord, optic nerves, and the white matter of the brain around the brain ventricles (fluid-filled spaces inside of the brain).

Figure 1. Multiple sclerosis MRI

Footnote: 25 year old male with left sided numbness and intermittent tingling. Characteristic and extensive changes consistent with multiple sclerosis are demonstrated, easily satisfying both discrimination in time and dissemination and space criteria (McDonald’s revised 2010 criteria). Widespread periventricular, juxtacortical, post fossa and upper cervical cord high T2 regions are noted, with at least a dozen demonstrating varying degrees of contrast enhancement and restricted diffusion indicating active/recent demyelination. The remainder of the brain is within normal limits, with no intra or extraaxial collection, mass or region of abnormal contrast enhancement.

[Source 3 ]What causes multiple sclerosis?

The ultimate cause of multiple sclerosis is damage to myelin, nerve fibers, and neurons in the brain and spinal cord, which together make up the central nervous system (CNS). But how that happens, and why, are questions that challenge researchers. Evidence appears to show that MS is a disease caused by genetic vulnerabilities combined with environmental factors.

Although there is little doubt that the immune system contributes to the brain and spinal cord tissue destruction of MS, the exact target of the immune system attacks and which immune system cells cause the destruction isn’t fully understood.

Researchers have several possible explanations for what might be going on. The immune system could be:

- fighting some kind of infectious agent (for example, a virus) that has components which mimic components of the brain (molecular mimickry)

- destroying brain cells because they are unhealthy

- mistakenly identifying normal brain cells as foreign.

The last possibility has been the favored explanation for many years. Research now suggests that the first two activities might also play a role in the development of MS. There is a special barrier, called the blood-brain barrier, which separates the brain and spinal cord from the immune system. If there is a break in the barrier, it exposes the brain to the immune system for the first time. When this happens, the immune system may misinterpret the brain as “foreign.”

Genetic susceptibility

Susceptibility to MS may be inherited. Studies of families indicate that relatives of an individual with MS have an increased risk for developing the disease. Experts estimate that about 15 percent of individuals with MS have one or more family members or relatives who also have MS. But even identical twins, whose DNA is exactly the same, have only a 1 in 3 chance of both having the disease. This suggests that MS is not entirely controlled by genes. Other factors must come into play.

Current research suggests that dozens of genes and possibly hundreds of variations in the genetic code (called gene variants) combine to create vulnerability to MS. Some of these genes have been identified. Most of the genes identified so far are associated with functions of the immune system. Additionally, many of the known genes are similar to those that have been identified in people with other autoimmune diseases as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus. Researchers continue to look for additional genes and to study how they interact with each other to make an individual vulnerable to developing MS.

Sunlight and vitamin D

A number of studies have suggested that people who spend more time in the sun and those with relatively high levels of vitamin D are less likely to develop MS. Bright sunlight helps human skin produce vitamin D. Researchers believe that vitamin D may help regulate the immune system in ways that reduce the risk of MS. People from regions near the equator, where there is a great deal of bright sunlight, generally have a much lower risk of MS than people from temperate areas such as the United States and Canada. Other studies suggest that people with higher levels of vitamin D generally have less severe MS and fewer relapses.

Smoking

A number of studies have found that people who smoke are more likely to develop MS. People who smoke also tend to have more brain lesions and brain shrinkage than non-smokers. The reasons for this are currently unclear.

Infectious factors and viruses

A number of viruses have been found in people with MS, but the virus most consistently linked to the development of MS is Epstein Barr virus (EBV), the virus that causes mononucleosis.

Only about 5 percent of the population has not been infected by EBV. These individuals are at a lower risk for developing MS than those who have been infected. People who were infected with EBV in adolescence or adulthood and who therefore develop an exaggerated immune response to EBV are at a significantly higher risk for developing MS than those who were infected in early childhood. This suggests that it may be the type of immune response to EBV that predisposes to MS, rather than EBV infection itself. However, there is still no proof that EBV causes MS.

Autoimmune and inflammatory processes

Tissue inflammation and antibodies in the blood that fight normal components of the body and tissue in people with MS are similar to those found in other autoimmune diseases. Along with overlapping evidence from genetic studies, these findings suggest that MS results from some kind of disturbed regulation of the immune system.

Multiple sclerosis signs and symptoms

The symptoms of multiple sclerosis usually begin over one to several days, but in some forms, they may develop more slowly. They may be mild or severe and may go away quickly or last for months. Sometimes the initial symptoms of MS are overlooked because they disappear in a day or so and normal function returns. Because symptoms come and go in the majority of people with MS, the presence of symptoms is called an attack, or in medical terms, an exacerbation. Recovery from symptoms is referred to as remission, while a return of symptoms is called a relapse. This form of MS is therefore called relapsing-remitting MS, in contrast to a more slowly developing form called primary progressive MS. Progressive MS can also be a second stage of the illness that follows years of relapsing-remitting symptoms.

A diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is often delayed because MS shares symptoms with other neurological conditions and diseases.

The first symptoms of MS often include:

- vision problems such as blurred or double vision or optic neuritis, which causes pain in the eye and a rapid loss of vision.

- weak, stiff muscles, often with painful muscle spasms

- tingling or numbness in the arms, legs, trunk of the body, or face

- clumsiness, particularly difficulty staying balanced when walking

- bladder control problems, either inability to control the bladder or urgency

- dizziness that doesn’t go away

Multiple sclerosis may also cause later symptoms such as:

- mental or physical fatigue which accompanies the above symptoms during an attack

- mood changes such as depression or euphoria

- changes in the ability to concentrate or to multitask effectively

- difficulty making decisions, planning, or prioritizing at work or in private life.

Some people with MS develop transverse myelitis, a condition caused by inflammation in the spinal cord. Transverse myelitis causes loss of spinal cord function over a period of time lasting from several hours to several weeks. It usually begins as a sudden onset of lower back pain, muscle weakness, or abnormal sensations in the toes and feet, and can rapidly progress to more severe symptoms, including paralysis. In most cases of transverse myelitis, people recover at least some function within the first 12 weeks after an attack begins. Transverse myelitis can also result from viral infections, arteriovenous malformations, or neuroinflammatory problems unrelated to MS. In such instances, there are no plaques in the brain that suggest previous MS attacks.

Neuro-myelitis optica is a disorder associated with transverse myelitis as well as optic nerve inflammation. Patients with this disorder usually have antibodies against a particular protein in their spinal cord, called the aquaporin channel. These patients respond differently to treatment than most people with MS.

Most individuals with MS have muscle weakness, often in their hands and legs. Muscle stiffness and spasms can also be a problem. These symptoms may be severe enough to affect walking or standing. In some cases, MS leads to partial or complete paralysis. Many people with MS find that weakness and fatigue are worse when they have a fever or when they are exposed to heat. MS exacerbations may occur following common infections.

Tingling and burning sensations are common, as well as the opposite, numbness and loss of sensation. Moving the neck from side to side or flexing it back and forth may cause “Lhermitte’s sign,” a characteristic sensation of MS that feels like a sharp spike of electricity coursing down the spine.

While it is rare for pain to be the first sign of MS, pain often occurs with optic neuritis and trigeminal neuralgia, a neurological disorder that affects one of the nerves that runs across the jaw, cheek, and face. Painful spasms of the limbs and sharp pain shooting down the legs or around the abdomen can also be symptoms of MS.

Most individuals with MS experience difficulties with coordination and balance at some time during the course of the disease. Some may have a continuous trembling of the head, limbs, and body, especially during movement, although such trembling is more common with other disorders such as Parkinson’s disease.

Fatigue is common, especially during exacerbations of MS. A person with MS may be tired all the time or may be easily fatigued from mental or physical exertion.

Urinary symptoms, including loss of bladder control and sudden attacks of urgency, are common as MS progresses. People with MS sometimes also develop constipation or sexual problems.

Depression is a common feature of MS. A small number of individuals with MS may develop more severe psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and paranoia, or experience inappropriate episodes of high spirits, known as euphoria.

People with MS, especially those who have had the disease for a long time, can experience difficulty with thinking, learning, memory, and judgment. The first signs of what doctors call cognitive dysfunction may be subtle. The person may have problems finding the right word to say, or trouble remembering how to do routine tasks on the job or at home. Day-to-day decisions that once came easily may now be made more slowly and show poor judgment. Changes may be so small or happen so slowly that it takes a family member or friend to point them out.

What is the course of multiple sclerosis?

The course of MS is different for each individual, which makes it difficult to predict. For most people, it starts with a first attack, usually (but not always) followed by a full to almost-full recovery. Weeks, months, or even years may pass before another attack occurs, followed again by a period of relief from symptoms. This characteristic pattern is called relapsing-remitting MS.

Primary-progressive MS is characterized by a gradual physical decline with no noticeable remissions, although there may be temporary or minor relief from symptoms. This type of MS has a later onset, usually after age 40, and is just as common in men as in women.

Secondary-progressive MS begins with a relapsing-remitting course, followed by a later primary-progressive course. The majority of individuals with severe relapsing-remitting MS will develop secondary progressive MS if they are untreated.

Finally, there are some rare and unusual variants of MS. One of these is Marburg variant MS (also called malignant MS), which causes a swift and relentless decline resulting in significant disability or even death shortly after disease onset. Balo’s concentric sclerosis, which causes concentric rings of demyelination that can be seen on an MRI, is another variant type of MS that can progress rapidly.

Determining the particular type of MS is important because the current disease modifying drugs have been proven beneficial only for the relapsing-remitting types of MS.

What is an exacerbation or attack of multiple sclerosis?

An exacerbation—which is also called a relapse, flare-up, or attack—is a sudden worsening of MS symptoms, or the appearance of new symptoms that lasts for at least 24 hours. MS relapses are thought to be associated with the development of new areas of damage in the brain. Exacerbations are characteristic of relapsing-remitting MS, in which attacks are followed by periods of complete or partial recovery with no apparent worsening of symptoms.

An attack may be mild or its symptoms may be severe enough to significantly interfere with life’s daily activities. Most exacerbations last from several days to several weeks, although some have been known to last for months.

When the symptoms of the attack subside, an individual with MS is said to be in remission. However, MRI data have shown that this is somewhat misleading because MS lesions continue to appear during these remission periods. Patients do not experience symptoms during remission because the inflammation may not be severe or it may occur in areas of the brain that do not produce obvious symptoms. Research suggests that only about 1 out of every 10 MS lesions is perceived by a person with MS. Therefore, MRI examination plays a very important role in establishing an MS diagnosis, deciding when the disease should be treated, and determining whether treatments work effectively or not. It also has been a valuable tool to test whether an experimental new therapy is effective at reducing exacerbations.

How is multiple sclerosis diagnosed?

There is no single test used to diagnose MS. Doctors use a number of tests to rule out or confirm the diagnosis. There are many other disorders that can mimic MS. Some of these other disorders can be cured, while others require different treatments than those used for MS. Therefore it is very important to perform a thorough investigation before making a diagnosis.

In addition to a complete medical history, physical examination, and a detailed neurological examination, a doctor will order an MRI scan of the head and spine to look for the characteristic lesions of MS. MRI is used to generate images of the brain and/or spinal cord. Then a special dye or contrast agent is injected into a vein and the MRI is repeated. In regions with active inflammation in MS, there is disruption of the blood-brain barrier and the dye will leak into the active MS lesion.

Doctors may also order evoked potential tests, which use electrodes on the skin and painless electric signals to measure how quickly and accurately the nervous system responds to stimulation. In addition, they may request a lumbar puncture (sometimes called a “spinal tap”) to obtain a sample of cerebrospinal fluid. This allows them to look for proteins and inflammatory cells associated with the disease and to rule out other diseases that may look similar to MS, including some infections and other illnesses. MS is confirmed when positive signs of the disease are found in different parts of the nervous system at more than one time interval and there is no alternative diagnosis.

Multiple sclerosis treatment

There is still no cure for MS, but there are treatments for initial attacks, medications and therapies to improve symptoms, and recently developed drugs to slow the worsening of the disease. These new drugs have been shown to reduce the number and severity of relapses and to delay the long term progression of MS.

Treatments for attacks

The usual treatment for an initial MS attack is to inject high doses of a steroid drug, such as methylprednisolone, intravenously (into a vein) over the course of 3 to 5 days. It may sometimes be followed by a tapered dose of oral steroids. Intravenous steroids quickly and potently suppress the immune system, and reduce inflammation. Clinical trials have shown that these drugs hasten recovery.

The American Academy of Neurology recommends using plasma exchange as a secondary treatment for severe flare-ups in relapsing forms of MS when the patient does not have a good response to methylprednisolone. Plasma exchange, also known as plasmapheresis, involves taking blood out of the body and removing components in the blood’s plasma that are thought to be harmful. The rest of the blood, plus replacement plasma, is then transfused back into the body. This treatment has not been shown to be effective for secondary progressive or chronic progressive forms of MS.

In March 2019 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved siponimod tablets (Mayzent) taken orally to treat adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis, to include clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease.

Treatments to help reduce disease activity and progression

During the past 20 years, researchers have made major breakthroughs in MS treatment due to new knowledge about the immune system and the ability to use MRI to monitor MS in patients. As a result, a number of medical therapies have been found to reduce relapses in persons with relapsing-remitting MS. These drugs are called disease modulating drugs.

There is debate among doctors about whether to start disease modulating drugs at the first signs of MS or to wait until the course of the disease is better defined before beginning treatment. On one hand, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications to treat MS work best early in the course of the disease and work poorly, if at all, later in the progressive phase of the illness. Clinical trials have shown convincingly that delaying treatment, even for the 1 to-2 years that it may take for patients with MS to develop a second clinical attack, may lead to an irreversible increase in disability. In addition, people who begin treatment after their first attack have fewer brain lesions and fewer relapses over time.

On the other hand, initiating treatment in patients with a single attack and no signs of previous MS lesions, before MS is diagnosed, poses risks because all FDA-approved medications to treat MS are associated with some side effects. Therefore, the best strategy is to have a thorough diagnostic work-up at the time of first attack of MS. The work-up should exclude all other diseases that can mimic MS so that the diagnosis can be determined with a high probability. The diagnostic tests may include an evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid and repeated MRI examinations. If such a thorough work-up cannot confirm the diagnosis of MS with certainty, it may be prudent to wait before starting treatment. However, each patient should have a scheduled follow-up evaluation by his or her neurologist 6 to 12 months after the initial diagnostic evaluation, even in the absence of any new attacks of the disease. Ideally, this evaluation should include an MRI examination to see if any new MS lesions have developed without causing symptoms.

Until recently, it appeared that a minority of people with MS had very mild disease or “benign MS” and would never get worse or become disabled. This group makes up 10 to 20 percent of those with MS. Doctors were concerned about exposing such benign MS patients to the side effects of MS drugs. However, recent data from the long-term follow-up of these patients indicate that after 10 to 20 years, some of these patients become disabled. Therefore, current evidence supports discussing the start of therapy early with all people who have MS, as long as the MS diagnosis has been thoroughly investigated and confirmed. There is an additional small group of individuals (approximately 1 percent) whose course will progress so rapidly that they will require aggressive and perhaps even experimental treatment.

The current FDA-approved therapies for MS are designed to modulate or suppress the inflammatory reactions of the disease. They are most effective for relapsing-remitting MS at early stages of the disease. These treatments include injectable beta interferon drugs. Interferons are signaling molecules that regulate immune cells. Potential side effects of beta interferon drugs include flu-like symptoms, such as fever, chills, muscle aches, and fatigue, which usually fade with continued therapy. A few individuals will notice a decrease in the effectiveness of the drugs after 18 to 24 months of treatment due to the development of antibodies that neutralize the drugs’ effectiveness. If the person has flare-ups or worsening symptoms, doctors may switch treatment to alternative drugs.

Glatiramer acetate is another injectable immune-modulating drug used for MS. Exactly how it works is not entirely clear, but research has shown that it changes the balance of immune cells in the body. Side effects with glatiramer acetate are usually mild, but it can cause skin reactions and allergic reactions. It is approved only for relapsing forms of MS.

The drug mitoxantrone, which is administered intravenously four times a year, has been approved for especially severe forms of relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive MS. This drug has been associated with development of certain types of blood cancers in up to one percent of patients, as well as with heart damage. Therefore, this drug should be used as a last resort to treat patients with a form of MS that leads to rapid loss of function and for whom other treatments did not stop the disease.

Natalizumab works by preventing cells of the immune system from entering the brain and spinal cord. It is administered intravenously once a month. It is a very effective drug for many people, but it is associated with an increased risk of a potentially fatal viral infection of the brain called progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML). People who take natalizumab must be carefully monitored for symptoms of PML, which include changes in vision, speech, and balance that do not remit like an MS attack. Therefore, natalizumab is generally recommended only for individuals who have not responded well to the other approved MS therapies or who are unable to tolerate them. Other side effects of natalizumab treatment include allergic and hypersensitivity reactions.

In 2010, the FDA approved fingolimod, the first MS drug that can be taken orally as a pill, to treat relapsing forms of MS. The drug prevents white blood cells called lymphocytes from leaving the lymph nodes and entering the blood and the brain and spinal cord. The decreased number of lymphocytes in the blood can make people taking fingolimod more susceptible to infections. The drug may also cause problems with eyes and with blood pressure and heart rate. Because of this, the drug must be administered in a doctor’s office for the first time and the treating physician must evaluate the patient’s vision and blood pressure during an early follow-up examination. The exact frequency of rare side effects (such as severe infections) of fingolimod is unknown.

In March 2017, the FDA approved ocrelizumab (brand name Ocrevus) to treat adults with relapsing forms of MS and promary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Other FDA-approved drugs to treat relapsing forms of MS in adults include dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide, both taken orally.

Table 1. Multiple Sclerosis Disease Modifying Drugs

| Trade Name | Generic Name |

|---|---|

| Avonex | interferon beta-1a |

| Betaseron | interferon beta-1b |

| Rebif | interferon beta-1a |

| Copaxone | glatiramer acetate |

| Tysabri | natalizumab |

| Novantrone | mitoxantrone |

| Gilenya | fingolimod |

Multiple sclerosis symptoms treatment

MS causes a variety of symptoms that can interfere with daily activities but which can usually be treated or managed to reduce their impact. Many of these issues are best treated by neurologists who have advanced training in the treatment of MS and who can prescribe specific medications to treat the problems.

Vision problems

Eye and vision problems are common in people with MS but rarely result in permanent blindness. Inflammation of the optic nerve or damage to the myelin that covers the optic nerve and other nerve fibers can cause a number of symptoms, including blurring or graying of vision, blindness in one eye, loss of normal color vision, depth perception, or a dark spot in the center of the visual field (scotoma).

Uncontrolled horizontal or vertical eye movements (nystagmus) and “jumping vision” (opsoclonus) are common to MS, and can be either mild or severe enough to impair vision.

Double vision (diplopia) occurs when the two eyes are not perfectly aligned. This occurs commonly in MS when a pair of muscles that control a specific eye movement aren’t coordinated due to weakness in one or both muscles. Double vision may increase with fatigue or as the result of spending too much time reading or on the computer. Periodically resting the eyes may be helpful.

Weak muscles, stiff muscles, painful muscle spasms, and weak reflexes

Muscle weakness is common in MS, along with muscle spasticity. Spasticity refers to muscles that are stiff or that go into spasms without any warning. Spasticity in MS can be as mild as a feeling of tightness in the muscles or so severe that it causes painful, uncontrolled spasms. It can also cause pain or tightness in and around the joints. It also frequently affects walking, reducing the normal flexibility or “bounce” involved in taking steps.

Tremor

People with MS sometimes develop tremor, or uncontrollable shaking, often triggered by movement. Tremor can be very disabling. Assistive devices and weights attached to limbs are sometimes helpful for people with tremor. Deep brain stimulation& and drugs such as clonazepam also may be useful.

Problems with walking and balance

Many people with MS experience difficulty walking. In fact, studies indicate that half of those with relapsing-remitting MS will need some kind of help walking within 15 years of their diagnosis if they remain untreated. The most common walking problem in people with MS experience is ataxia—unsteady, uncoordinated movements—due to damage with the areas of the brain that coordinate movement of muscles. People with severe ataxia generally benefit from the use of a cane, walker, or other assistive device. Physical therapy can also reduce walking problems in many cases.

In 2010, the FDA approved the drug dalfampridine to improve walking in patients with MS. It is the first drug approved for this use. Clinical trials showed that patients treated with dalfampridine had faster walking speeds than those treated with a placebo pill.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a common symptom of MS and may be both physical (for example, tiredness in the legs) and psychological (due to depression). Probably the most important measures people with MS can take to counter physical fatigue are to avoid excessive activity and to stay out of the heat, which often aggravates MS symptoms. On the other hand, daily physical activity programs of mild to moderate intensity can significantly reduce fatigue. An antidepressant such as fluoxetine may be prescribed if the fatigue is caused by depression. Other drugs that may reduce fatigue in some individuals include amantadine and modafinil.

Fatigue may be reduced if the person receives occupational therapy to simplify tasks and/or physical therapy to learn how to walk in a way that saves physical energy or that takes advantage of an assistive device. Some people benefit from stress management programs, relaxation training, membership in an MS support group, or individual psychotherapy. Treating sleep problems and MS symptoms that interfere with sleep (such as spastic muscles) may also help.

Pain

People with MS may experience several types of pain during the course of the disease.

Trigeminal neuralgia is a sharp, stabbing, facial pain caused by MS affecting the trigeminal nerve as it exits the brainstem on its way to the jaw and cheek. It can be treated with anticonvulsant or antispasmodic drugs, alcohol injections, or surgery.

People with MS occasionally develop central pain, a syndrome caused by damage to the brain and/or spinal cord. Drugs such as gabapentin and nortryptiline sometimes help to reduce central pain.

Burning, tingling, and prickling (commonly called “pins and needles”) are sensations that happen in the absence of any stimulation. The medical term for them is dysesthesias” They are often chronic and hard to treat.

Chronic back or other musculoskeletal pain may be caused by walking problems or by using assistive aids incorrectly. Treatments may include heat, massage, ultrasound treatments, and physical therapy to correct faulty posture and strengthen and stretch muscles.

Problems with bladder control and constipation

The most common bladder control problems encountered by people with MS are urinary frequency, urgency, or the loss of bladder control. The same spasticity that causes spasms in legs can also affect the bladder. A small number of individuals will have the opposite problem—retaining large amounts of urine. Urologists can help with treatment of bladder-related problems. A number of medical treatments are available. Constipation is also common and can be treated with a high-fiber diet, laxatives, and other measures.

Sexual issues

People with MS sometimes experience sexual problems. Sexual arousal begins in the central nervous system, as the brain sends messages to the sex organs along nerves running through the spinal cord. If MS damages these nerve pathways, sexual response—including arousal and orgasm—can be directly affected. Sexual problems may also stem from MS symptoms such as fatigue, cramped or spastic muscles, and psychological factors related to lowered self-esteem or depression. Some of these problems can be corrected with medications. Psychological counseling also may be helpful.

Depression

Studies indicate that clinical depression is more frequent among people with MS than it is in the general population or in persons with many other chronic, disabling conditions. MS may cause depression as part of the disease process, since it damages myelin and nerve fibers inside the brain. If the plaques are in parts of the brain that are involved in emotional expression and control, a variety of behavioral changes can result, including depression. Depression can intensify symptoms of fatigue, pain, and sexual dysfunction. It is most often treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant medications, which are less likely than other antidepressant medications to cause fatigue.

Inappropriate laughing or crying

MS is sometimes associated with a condition called pseudobulbar affect that causes inappropriate and involuntary expressions of laughter, crying, or anger. These expressions are often unrelated to mood; for example, the person may cry when they are actually very happy, or laugh when they are not especially happy. In 2010 the FDA approved the first treatment specifically for pseudobulbar affect, a combination of the drugs dextromethorphan and quinidine. The condition can also be treated with other drugs such as amitriptyline or citalopram.

Cognitive changes

Half -to three-quarters of people with MS experience cognitive impairment, which is a phrase doctors use to describe a decline in the ability to think quickly and clearly and to remember easily. These cognitive changes may appear at the same time as the physical symptoms or they may develop gradually over time. Some individuals with MS may feel as if they are thinking more slowly, are easily distracted, have trouble remembering, or are losing their way with words. The right word may often seem to be on the tip of their tongue.

Some experts believe that it is more likely to be cognitive decline, rather than physical impairment, that causes people with MS to eventually withdraw from the workforce. A number of neuropsychological tests have been developed to evaluate the cognitive status of individuals with MS. Based on the outcomes of these tests, a neuropsychologist can determine the extent of strengths and weaknesses in different cognitive areas. Drugs such as donepezil, which is usually used for Alzheimer’s disease, may be helpful in some cases.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome

Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare clinical entity that is characterized by noninflammatory demyelination afflicting the central pons, basal ganglia, thalami, peripheral cortex, and hippocampi 4. Osmotic demyelination syndrome is caused by the destruction of the layer (myelin sheath) covering nerve cells in the middle of the brainstem (pons). Histopathologically, there is a destruction of myelin sheaths sparing the underlying neuronal axons due to the susceptibility of oligodendrocytes to rapid osmotic shifts often encountered in chronically debilitated patients.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a debilitating, potentially fatal disorder which includes two components – central pontine myelinolysis (CPM) and extrapontine myelinolysis (EPM) 5. The central pontine myelinolysis (CPM) involves the basis pontis symmetrically, pontocerebellar fibers, and relatively spares the ventrolateral pons. Extrapontine myelinolysis (EPM) commonly involves the basal ganglia, thalami, and cerebral white matter 5. The underlying physiology is theorized due to damage to oligodendrocytes secondary to rapid changes in osmolarity. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality for the diagnosis and subsequent follow-up of brain parenchymal abnormalities due to this disorder.

Although, osmotic demyelination syndrome can occur in the presence of varied etiological factors 6, the primary pathophysiology described being either a reduced adaptive capacity of the neuroglia to large shifts in the serum osmolarity 7 or the cellular edema caused by fluctuations in electrolyte forces results in compression and subsequent demyelination of fiber tracts 8.

The outcome of osmotic demyelination syndrome is very dramatic ranging from the vegetative state to full neurological recovery 9. Various case reports of osmotic demyelination syndrome have been published from time to time with few case series out of which the largest being one studied in 58 patients 10. Though, the exact incidence of osmotic demyelination syndrome is not known, an autopsy based study documented a prevalence rate of 0.25–0.5% in the general population 9 and 10% in patients undergoing liver transplantation 11.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome causes

When the myelin sheath that covers nerve cells is destroyed, signals from one nerve to another aren’t properly transmitted. Although the brainstem is mainly affected, other areas of the brain can also be involved.

The most common cause of osmotic demyelination syndrome is a quick change in the body’s sodium levels. This most often occurs when someone is being treated for low blood sodium (hyponatremia) and the sodium is replaced too fast. Sometimes, it occurs when a high level of sodium in the body (hypernatremia) is corrected too quickly.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome does not usually occur on its own. Most often, it’s a complication of treatment for other problems, or from the other problems themselves.

Risks include:

- Alcohol use

- Liver disease

- Malnutrition from serious illnesses

- Radiation treatment of the brain

- Severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy

Osmotic demyelination syndrome symptoms

Osmotic demyelination syndrome symptoms may include any of the following:

- Confusion, delirium, hallucinations

- Balance problems, tremor

- Problem swallowing

- Reduced alertness, drowsiness or sleepiness, lethargy, poor responses

- Slurred speech

- Weakness in the face, arms, or legs, usually affecting both sides of the body

The classical picture is a patient who presented with seizures and altered sensorium due to hyponatremia, had a rapid recovery with normalization of serum sodium, but only to deteriorate again. This second phase correlates with a rapid correction of serum sodium levels and development of osmotic demyelination syndrome 12.

The clinical picture is usually very wide depending upon the area in the central nervous system involved with demyelination. When pons along with corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts are involved, the classical presentation is dysarthria and dysphagia along with flaccid paralysis changing over to spastic later on. Extra-pontine myelinolysis is characterized by tremor, ataxia and movement disorders like mutism, Parkinsonism, dystonia, and catatonia 13. If the lesion extends further, then it may result in pupillary, oculomotor dysfunction, and locked-in syndrome. When there is a combination of pontine and extra-pontine lesions, the clinical picture is usually mixed and variable 12.

It has been documented that osmotic demyelination syndrome has a peak incidence in adults with a male preponderance, possibly due to the association of risk factors like alcoholism in the particular age group.[10] We observed a similar male preponderance (64%) and none of the patients in this study belong to pediatric age range.

In this case series, out of 17 patients, 11 (64%) had altered sensorium as the most common clinical presentation while only 3 (17%) had episodes of seizures. Flaccid quadriparesis was seen in 6 patients (35%) and surprisingly, 64% of the patients had normal muscular tone.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome possible complications

Osmotic demyelination syndrome complications may include:

- Decreased ability to interact with others

- Decreased ability to work or care for self

- Inability to move, other than to blink eyes (“locked in” syndrome)

- Permanent nervous system damage

Osmotic demyelination syndrome diagnosis

The health care provider will perform a physical exam and ask about the symptoms.

A head MRI scan may reveal a problem in the brainstem (pons) or other parts of the brain. This is the main diagnostic test.

Other tests may include:

- Blood sodium level and other blood tests

- Brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER)

Figure 2. Osmotic demyelination syndrome MRI

Footnote: T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing symmetrical hyperintensity of midbrain and pons suggestive of both pontine and extra pontine myelinolysis

[Source 14 ]Osmotic demyelination syndrome treatment

Osmotic demyelination syndrome is an emergency disorder that needs to be treated in the hospital though most people with this condition are already in the hospital for another problem.

There is no known cure for central pontine myelinolysis. Treatment is focused on relieving symptoms.

Reports on random case reports and small case series have found benefits of a multiply of treatment modalities such as steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and thyrotrophin releasing hormone, re-induction hyponatremia, administration of organic osmolytes (urea, Myoinositol), and dopaminergic compounds, especially in extra-pontine myelinolysis cases etc 12. As there is no randomized human trial till date, all these possible therapies are not yet recommended in osmotic demyelination syndrome patients.

Physical therapy may help maintain muscle strength, mobility, and function in weakened arms and legs.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome prognosis

The nerve damage caused by central pontine myelinolysis is often long-lasting. The disorder can cause serious long-term (chronic) disability.

Abbott et al. 15 in a study of 34 osmotic demyelination syndrome patients reported a mortality of 6% whereas 30% completely recovered, 32% had some debilitating illness, but independent, and a similar number of patients were recovered but dependent. Martin reported in their review an overall mortality of 40–50% in osmotic demyelination syndrome and a lower rate in those subgroup of patients admitted in intensive therapy unit (10–20%) 12.

Literature evidence varies widely with regards to mortality ranging from 6% to 90% 16. Whereas Menger and Jörg reported 40% of patients recovered without any noticeable neurologic complications 16. One study had reported 25% of patients developed grave neurological outcome requiring lifelong support 17.

References- Cheon JE, Kim IO, Hwang YS et-al. Leukodystrophy in children: a pictorial review of MR imaging features. Radiographics. 22 (3): 461-76

- Sarbu N, Shih RY, Jones RV et-al. White Matter Diseases with Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2016;36 (5): 1426-47. doi:10.1148/rg.2016160031

- Multiple sclerosis. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/multiple-sclerosis-25

- Garg P, Aggarwal A, Malhotra R, Dhall S. Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome – Evolution of Extrapontine Before Pontine Myelinolysis on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2019;10(1):126–135. doi:10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_240_18 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6337981

- Pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Wright DG, Laureno R, Victor M. Brain. 1979 Jun; 102(2):361-85.

- Martin RJ. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: The osmotic demyelination syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(Suppl 3):iii22–8.

- Verbalis JG, Gullans SR. Rapid correction of hyponatremia produces differential effects on brain osmolyte and electrolyte reaccumulation in rats. Brain Res. 1993;606:19–27

- Singh N, Yu VL, Gayowski T. Central nervous system lesions in adult liver transplant recipients: Clinical review with implications for management. Medicine (Baltimore) 1994;73:110–8

- Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, Rojiani AM, Filley CM. Central and extrapontine myelinolysis: Then. and now. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:1–11

- Gocht A, Colmant HJ. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: A report of 58 cases. Clin Neuropathol. 1987;6:262–70

- Lampl C, Yazdi K. Central pontine myelinolysis. Eur Neurol. 2002;47:3–10

- Martin RJ. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: The osmotic demyelination syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(Suppl 3):iii22–8

- Abbott R, Silber E, Felber J, Ekpo E. Osmotic demyelination syndrome. BMJ. 2005;331:829–30.

- Rao PB, Azim A, Singh N, Baronia AK, Kumar A, Poddar B. Osmotic demyelination syndrome in Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19(3):166–169. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.152760 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4366916

- Abbott R, Silber E, Felber J, Ekpo E. Osmotic demyelination syndrome. BMJ. 2005;331:829–30

- Menger H, Jörg J. Outcome of central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis (n=44) J Neurol. 1999;246:700–5

- King JD, Rosner MH. Osmotic demyelination syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339:561–7