Double crush syndrome

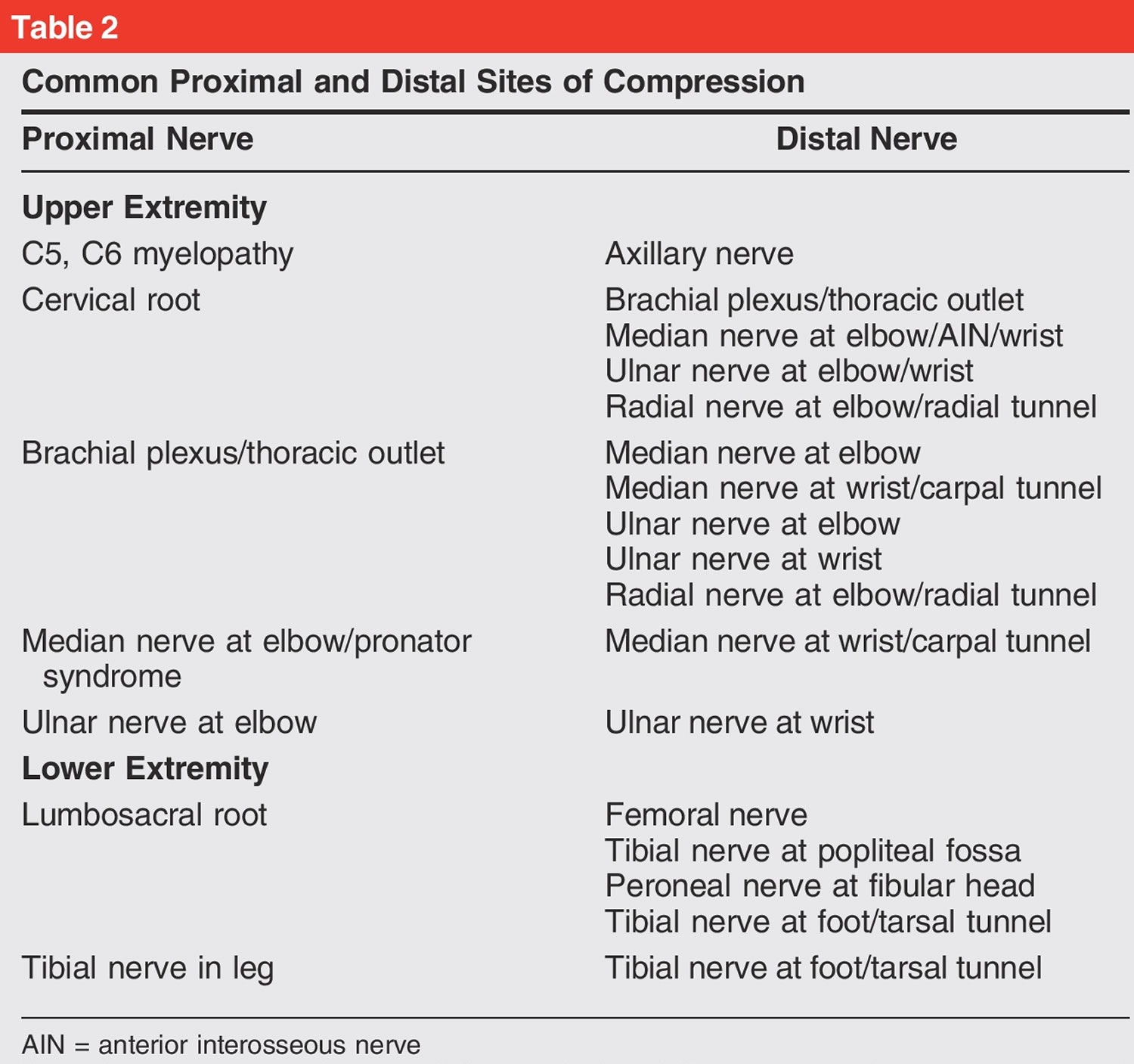

Double crush syndrome is refers to the coexistence of distinct compression at two or more locations along the course of a peripheral nerve 1. Compression along a peripheral nerve at multiple locations could contribute to the vague, nonspecific, or atypical symptoms of the patient and and these patients characteristically fail to improve after single site decompression surgery 2, 3. Double crush syndrome remains incompletely understood and optimal treatment paths are unclear 1. Upton and McComas in 1973 theorized that a proximal compression of a peripheral nerve could render the distal peripheral nerve more susceptible to injury due to a disruption in axonal flow or axon transport mechanism 4. The nerve cell body produces material that is necessary for normal function of the axon. The material travels distally along the axon. Break down products return in a proximal direction by the axonal transport system. Disruption of the synthesis or blocking of transport of these materials (antegrade/retrograde) increases sustainability of the axon to compression 5, 6, 7. Other investigators have noted neural ischemia, inherent elastic characteristics of the nerve, systemic diseases such as diabetes and thyroid disease, and chemotherapeutic agents in creating the “first hit” along a nerve that renders its distal segment prone to injury 8, 9. In 2011, a panel of 17 international experts was convened to determine the most likely mechanisms producing a peripheral nerve insult that would predispose the nerve to the development of another disorder. Fourteen mechanisms were identified through various rounds of surveying, of which 4 were identified as highly plausible. These were impaired axonal transport, ion channel upregulation or downregulation, inflammation in the dorsal root ganglions, and neuroma-in-continuity 10. For example, the commonest type of double crush syndrome is the one involving the median nerve (a mixed sensory and motor nerve) with the coexistence of carpal tunnel syndrome with cervical radiculopathy (cervical nerve root compression that occurs when a nerve in the neck is compressed or irritated where it branches away from the spinal cord) or brachial plexus compression 11, 12, 13, 14. You have 8 cervical nerves (C1 to C8), but those most commonly pinched are C5, C6, and C7. Except for the nerve roots, any other sites proximal to carpal tunnel along the median nerve can also serve as the proximal compression sites. Previous studies have shown double crush syndrome occurring between the cervical spine and the median nerve at a rate of 18% 15 with C5 and C6 being the most commonly affected nerve roots 13. Identifying which area of nerve compression or irritation, proximal or distal, is most responsible for a patient’s symptoms is often challenging for the clinician 16. Importantly, 30% of median nerve double crush patients considered their carpal tunnel release a failure, which may be likely related to persistent foraminal stenosis at the cervical spine 13. However, cervical radiculopathy should not have an effect on distal sensory conduction tests and on distal myelin; most of the patients with carpal tunnel syndrome were found to have prolonged sensory latency and focal demyelination at electrophysiological investigations 11. Electrodiagnostic studies of median nerve mononeuropathy failed to meet the anatomical and pathophysiological requirements of the double crush hypothesis in the majority of patients 17.

While the double crush most commonly involves carpal tunnel syndrome and C5 andC6 radiculopathy, it also can involve the ulnar nerve (entrapped at the elbow or less commonly in the hand) and C8 radiculopathy or “handcuff neuropathy” (superficial radial sensory nerve at the wrist) and C5 radiculopathy 18. Less frequently double crush syndrome occurs in the leg, which is supplied by 5 lumbar nerve roots (L1 to L5) and two sacral nerve roots (S1 and S2) 19. The most common double crush of the lower limb involves the common peroneal nerve at or near the knee and an L5 radiculopathy. Both can create weakness – a foot drop – which appears farther down the limb.

Double crush syndrome is a controversial diagnosis. A lot of debate exists among surgeons related to the existence of the double crush syndrome and the mechanisms that could be responsible for producing it 20. Although there exists a relationship between cervical radiculopathy and carpal tunnel syndrome, the cause of the double crush syndrome and the pathophysiology of the condition are still undetermined 10. Multiple studies have failed to recognize an electrodiagnostic correlation between patients with isolated carpal tunnel syndrome and those diagnosed with double crush syndrome 17. Furthermore, physical examination findings, such as the Tinel and Phalen signs, have also been shown to be unreliable as the sole method of evaluation in cases of suspected double crush syndrome, although they do correlate well with symptoms in patients with isolated carpal tunnel syndrome diagnosed by electrodiagnostic studies 17. In addition, Kwon et al 21, in 2006, evaluated the severity of carpal tunnel syndrome based on the level of confirmed cervical radiculopathy (C6, C7, C8) with electrophysiologic parameters of median motor and sensory nerves. The electrophysiologic results revealed no significant correlation between median sensory parameters in C6, C7 cases, and no relationship was observed between median motor responses and C8 radiculopathy 21.

Treatment strategies to improve clinical outcomes in patients with suspected double crush syndrome are not clearly defined 16. Osterman 13 has commented in an earlier investigation of patients with isolated carpal tunnel syndrome and those with double crush syndrome that surgical outcomes of carpal tunnel release were poorer in the double crush syndrome group than the isolated carpal tunnel syndrome group, suggesting that decompression of both sites is required for an optimal outcome. In one study, despite successful surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome, symptoms did not disappear to a satisfactory level in about 25% of the cases 22. Baba et al 23 also suggested the role of cervical decompression before peripheral nerve decompression or as the sole treatment in the management of double crush syndrome when symptoms and functional limitations were more related to cervical spine pathology. Regarding cubital tunnel syndrome, Galarza et al 24 suggested that anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis performed before ulnar nerve release at the elbow lead to less favorable outcomes.

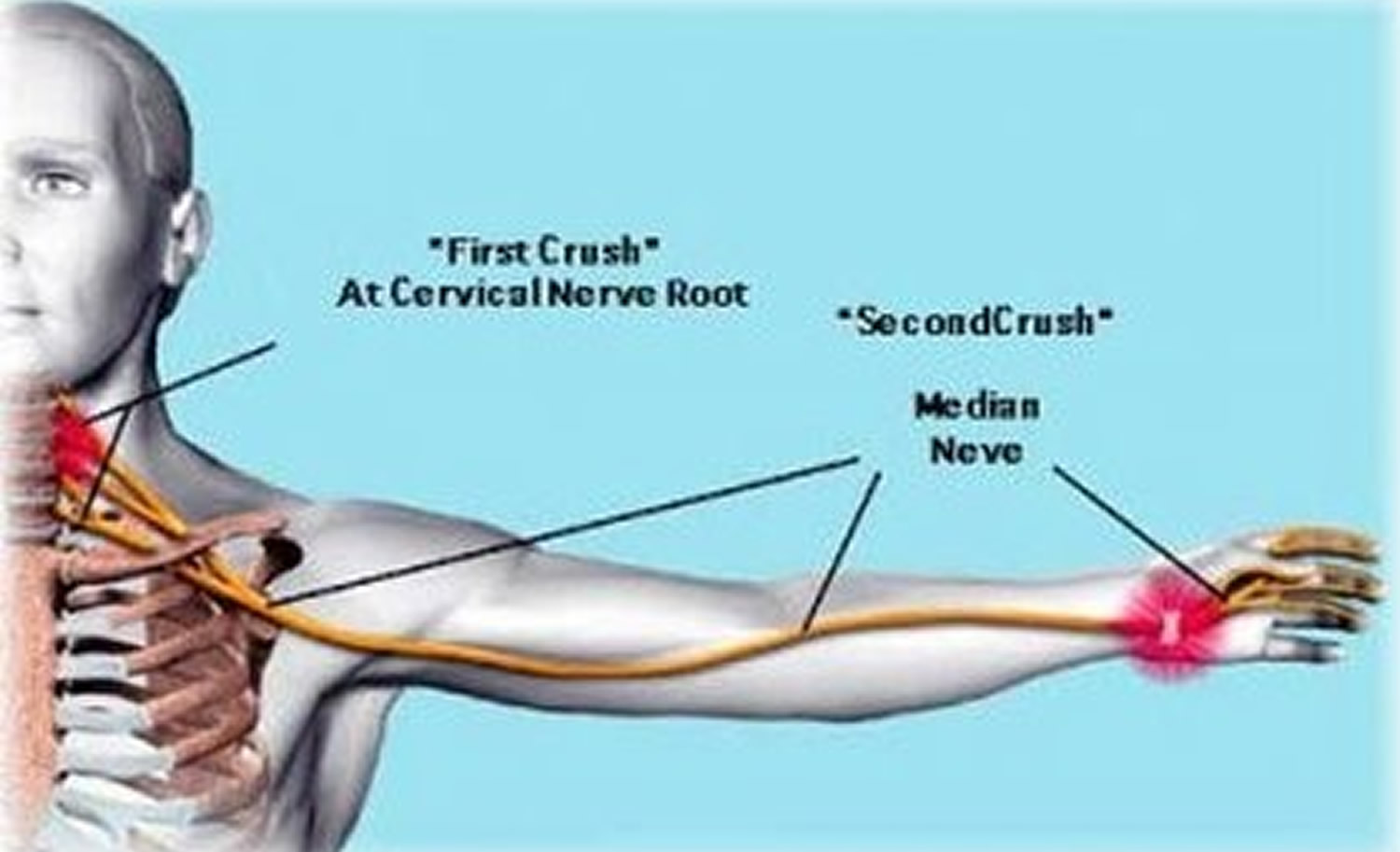

Figure 1. Double crush syndrome

Double crush syndrome signs and symptoms

Patients with double crush syndrome can experience a variety of symptoms. In addition to weakness, numbness, tingling, pins and needles and pain in the the hands, fingers or forearm, a person can also experience headaches and neck pain (if the neck is involved). The patient with double crush syndrome can also display a variety of clinical signs, such as a slouched posture with a forward head. As mentioned above, double crush syndrome involves two compression sites. An example of this could be a patient with carpal tunnel syndrome as well as having joint degeneration in the neck (which is also irritating and compressing the nerve). This can prove difficult for the clinician to detect and diagnose.

Typical presentation of double crush syndrome in the arms:

- Numbness and tingling in the hands, fingers or forearm

- Muscle weakness in the hand and forearm

- Reduced grip strength

- Increased pain and numbness in the upper limb with certain movements

Typical presentation of double crush syndrome in the legs:

- Numbness and tingling in the foot, toes or leg

- Muscle weakness in the leg

- Reduced movement at the ankle due to pain and/or weakness

Double crush syndrome causes

The cause and pathophysiology of double crush syndrome is controversial 25. It is still unclear why carpal tunnel syndrome and cervical radiculopathy are observed together 20. The classic description of double crush syndrome was first described in 1973 by Upton and McComas 4 who theorized that a proximal compression of a peripheral nerve could render the distal peripheral nerve more susceptible to injury due to a disruption in axonal flow or axon transport mechanism. The clinicians developed their postulate after clinical observation of patients presenting with peripheral nerve neuropathy who also had associated cervicothoracic nerve root pathology.

Double crush syndrome common sites of nerve compression:

- Cervical root compression (neck) and carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve wrist)

- Thoracic outlet syndrome (shoulder) and carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve wrist)

- Pronator teres syndrome (forearm) and carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve wrist)

- Cervical nerve root compression (neck) and cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve elbow)

- Thoracic outlet syndrome (shoulder) and cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve elbow)

- Cubital tunnel syndrome (ulnar nerve elbow) and Guyon’s canal Syndrome (ulnar nerve wrist)

- Cervical nerve root compression (neck) and radial tunnel syndrome (radial nerve elbow)

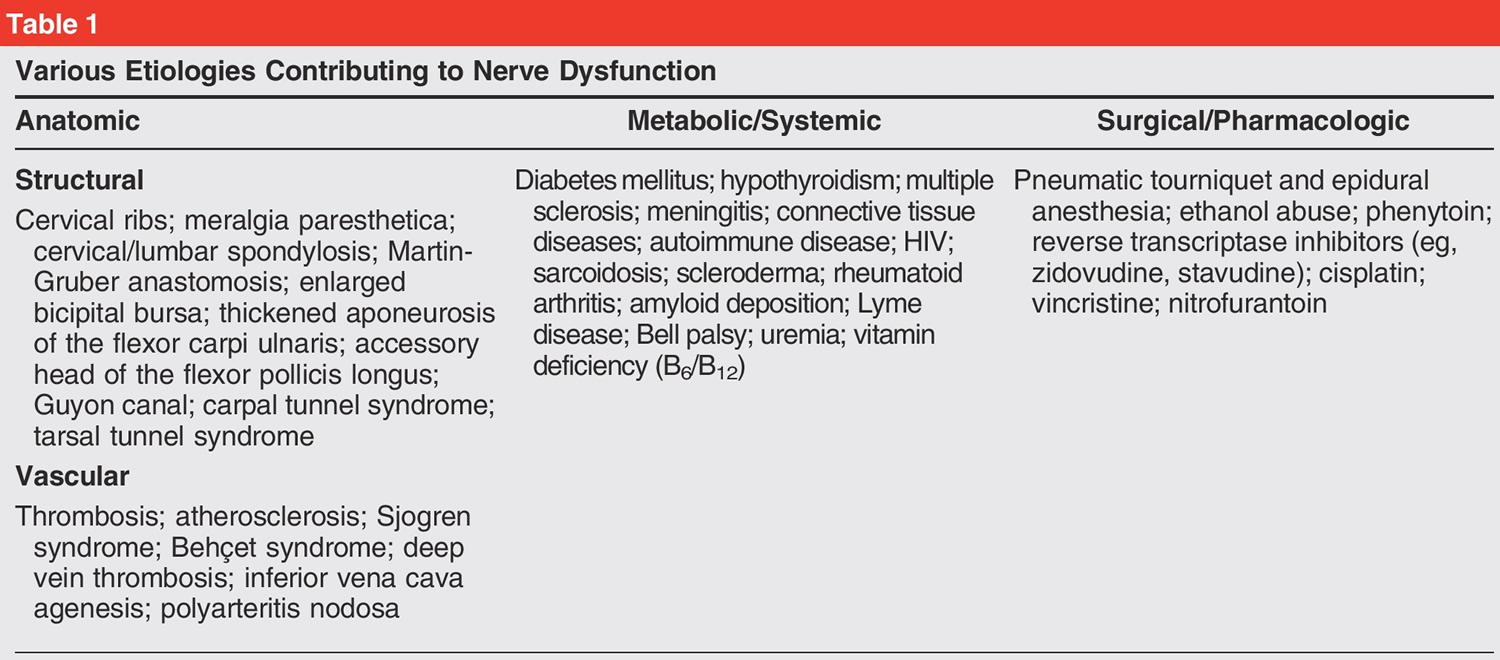

In 1987, Nemoto et al 7 studied a canine compression model and concluded that “a double lesion was greater than the sum of the deficits after each separate lesion.” This idea of a summation injury was supported in another animal model by Dellon and Mackinnon 26; the authors examined a rat sciatic nerve compression model and concluded that “the existence of two sites of simultaneous compression will result in significantly poorer neural function than will a single site of compression.” However, other studies have challenged double crush syndrome as it was originally proposed. Wilbourn and Gilliatt 27 questioned the accuracy of double crush syndrome. In their critical analysis of double crush syndrome, the authors systematically illustrated anatomic, physiologic, and pathologic disease processes, which they argue did not justify the diagnosis of double crush syndrome as originally defined. Further supporting this dissenting opinion, multiple authors have produced electrophysiologic studies that fail to demonstrate an adequate neurophysiologic explanation to support the initial concept of double crush syndrome 28. The original definition of double crush syndrome, although based on sound pathophysiologic processes, may be limited in scope because investigators have shown that compressive pathology is not the only contributor to nerve pathology. Despite the controversy surrounding the diagnosis, double crush syndrome is an important concept because it emphasizes the fact that patients’ symptoms may not simply be related to one anatomic site of compression but may also be caused by a remote compressive lesion or a systemic process, such as peripheral neuropathy.

In 2011, a panel of 17 international experts was convened to determine the most likely mechanisms producing a peripheral nerve insult that would predispose the nerve to the development of another disorder. Fourteen mechanisms were identified through various rounds of surveying, of which 4 were identified as highly plausible. These were impaired axonal transport 29, alteration of nerve elasticity 30, ion channel upregulation or downregulation, decreased intraneural microcirculation 31, 32, inflammation in the dorsal root ganglions, and neuroma-in-continuity 10. Other investigators have noted neural ischemia, systemic diseases such as diabetes and thyroid disease, and chemotherapeutic agents in creating the “first hit” along a nerve that renders its distal segment prone to injury 8, 9.

Compared with the upper extremity, less literature is available on lower extremity double crush syndrome. However, the concept and proposed pathophysiology is applicable to any nerve, and clear examples of double crush syndrome involving the lumbar roots and requisite peripheral nerves have been described. Giannoudis et al 33 reported an increased risk and poor prognosis for patients with acetabular fractures with proximal and distal nerve injury. Nine of 27 patients (33%) with initial neurologic injury who underwent fixation of an acetabular fracture had evidence of neuropathy involving the sciatic nerve proximally and the peroneal nerve distally at the neck of the fibula. In a study by Sunderland 34, all patients with double crush syndrome pathology showed poor recovery.

Trauma may contribute to lower extremity double crush syndrome. Several reports note the high incidence of sciatic nerve injury, ranging from 10% to 25% in patients with posterior hip dislocation and acetabular fracture 35. Golovchinsky 36 showed an overlap of distal peripheral entrapment in the lower extremities in patients with lumbar neural compression. Another clinical example of lower extremity double crush syndrome is represented by tarsal tunnel syndrome in which the posterior tibial nerve is compressed under the flexor retinaculum. In a case series of three patients, tarsal tunnel syndrome was diagnosed after an acute event proximal to and not involving the ankle, representing a double crush syndrome 37.

[Source 25 ] [Source 25 ]Double crush syndrome pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathy is complex, and controversy surrounds the exact underlying mechanisms of double crush syndrome. Multiple authors have proposed various explanations; the most accepted principle for double crush syndrome involves a primary nerve disorder that predisposes the nerve to further injury. The proposed pathophysiology of double crush syndrome is the disruption of nutrient flow in both antegrade and retrograde directions along the axon.

In a Delphi study 10, international experts concluded that four mechanisms were highly plausible: axonal transport, immune-response inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia, ion channel regulation, and neuroma-in-continuity. As mentioned earlier, several animal studies have confirmed that increased pressure levels can impair axonal transport; however, debate still remains as to the exact resultant effect. Although animal studies can demonstrate impaired nerve function with prolonged compression, there is no evidence that compression at two points along a nerve creates a distinct pathophysiologic entity.

Double crush syndrome risk factors

Multiple retrospective studies have attempted to identify predictive risk factors for double crush syndrome. Lo et al 17 analyzed 765 patient medical records and electrodiagnostic reports of patients with suspected carpal tunnel syndrome and cervical radiculopathy; 151 patients (20%) had only carpal tunnel syndrome, 362 (47%) had only cervical radiculopathy, and 198 (26%) were diagnosed with both conditions. In this study, women were more susceptible to carpal tunnel compression and/or double crush syndrome than were men. However, men were more susceptible to cervical radiculopathy. This finding is consistent with other studies that suggest that men are more prone to cervical radiculopathy and women are more prone to carpal tunnel syndrome 38. However, the evidence surrounding double crush syndrome is inconsistent; conflicting studies report a higher incidence of double crush syndrome in men compared with women 39. This lack of consistency between studies highlights the complexity of the pathologic processes that contribute to double crush syndrome symptomatology.

Multiple studies have illustrated the increased susceptibility of nerves to compressive pathology secondary to systemic illness. Baba et al 40 reported an increased incidence of multiple compressive peripheral neuropathies in patients with diabetes, finding a 16% incidence of patients with both carpal tunnel syndrome and cubital tunnel syndrome. Various pharmacologic agents, infectious pathology, and many conditions, such as anatomic abnormalities, hypothyroidism, hereditary neuropathy, uremic neuropathy, vitamin deficiency, and chronic alcoholism, can alter neural physiology and consequently put peripheral nerves at similar risk 40.

Double crush syndrome diagnosis

The diagnosis of double crush syndrome is typically made when patients are dissatisfied with the result of carpal tunnel release. Osterman 41 conducted a prospective study of patients with carpal tunnel release and found that 90% of patients with concomitant cervical radiculopathy had proximal radiation of pain compared with 50% of patients with carpal tunnel release alone. It was also noted that fewer than half the patients with concomitant cervical radiculopathy had median nerve paresthesias compared with 93% of patients with carpal tunnel release alone. Osterman 41 also found distinctive differences between double crush syndrome and isolated carpal tunnel release. In his prospective study evaluating patients presenting with upper extremity pain, patients with double crush syndrome reported more paresthesias and less numbness compared with those with carpal tunnel release alone. Less than half the patients with double crush syndrome had distal median symptoms compared with 93% of those with carpal tunnel release alone. Grip strength was subjectively weaker in patients with double crush syndrome compared with those with carpal tunnel release.

Other investigators have attempted to further elucidate these subtle differences. Lo et al 42 found that the hallmark physical examination findings of carpal tunnel release (ie, Tinel sign, Phalen test) were more frequently positive in patients with carpal tunnel release only (36.4% and 33.8%, respectively), compared with those with double crush syndrome only (18.7% for each test) or sole cervical radiculopathy (12.7% and 10.2%, respectively). These studies illustrate the importance of the diagnosing physician having an astute understanding of classic presentations and understanding the subtle differences that may help distinguish double crush syndrome from a simpler single compression syndrome. Many patients have both cervical spondylosis (an expected part of aging) and carpal tunnel release (a very common, genetically mediated narrowing of the carpal tunnel), but it is not currently possible to determine when these pathophysiologies are synergistic rather than just coexistent.

During evaluation for possible double crush syndrome, cervical radiographs are not recommended because 75% of patients in the seventh decade of life have degenerative radiographic changes; additionally, findings on radiographs are commonly similar between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients 43. MRI is the test of choice for most patients who require cervical spine imaging; however, MRI must be interpreted with caution because of the high incidence of asymptomatic patients with cervical spine pathology 44.

Ultrasonography has been proposed as a useful adjuvant tool to improve electrophysiologic testing for the diagnosis of peripheral nerve conditions. Given the inexpensive, noninvasive nature of ultrasonography, its use is likely to become more common in the future 45 and further research into the utility of ultrasonography is warranted. However, at this time, there is no absolute confirmatory test, and an accurate diagnosis requires the summation of history, physical examination results, and diagnostic testing.

Double crush syndrome treatment

Initially, conservative treatment should be trialed with distinct management that focuses on the unique pathology and symptomatology of each lesion 25. Cervical nerve root compression may be initially treated with oral steroids, avoidance of irritating movements, a short period of immobilization with a soft collar, and physical therapy. Common palliative treatments of distal lesions of compressive neuropathies include splinting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and steroid injections. The surgeon who makes the diagnosis of double crush syndrome initially provides standard nonsurgical management of each suspected level of nerve compression.

It is important for the physician to consider the benefits versus the adverse effects with each patient and plan on having the patient take an active role in his or her treatment plan. Interestingly, lack of clinical improvement with carpal tunnel injection may be used as a predictor for poor surgical improvement with carpal tunnel release alone because patients with double crush syndrome may have a suboptimal response to injection 41. Osterman 41 found that 33% of patients with both carpal tunnel syndrome and cervical radiculopathy viewed release of the carpal tunnel as a failure, compared with 7% in those with carpal tunnel syndrome alone. Nonsurgical management of thoracic outlet syndrome may include exercise and bracing to widen the thoracic outlet 46; surgical treatment would involve excision of any anomalous offending anatomy.

Most surgical treatments of dual compression in the upper extremity focus on cervical spine decompression and surgical release of the compressive site distally. Determining the need for one or both surgeries and the order in which to pursue the surgeries can be challenging; the decision should be based on the severity of compression and symptomatology at each site. Surgical treatment options for cervical neuroforaminal stenosis include anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion, total disk replacement, and posterior laminoforaminotomy. Surgical options for thoracic outlet syndrome include first rib resection or resection of an offending muscle 46. Surgical treatment of distal compression is performed by releasing the compressing structure to relieve pressure on the nerve. In patients with dual compression, surgical treatment may be less effective than that performed for those with only one site of compression if both sites are compressed.

Surgical outcomes for the treatment of double crush syndrome are difficult to study. Although a sham-surgery, placebo-controlled study would be optimal to investigate the effectiveness of intervention for double crush syndrome, this would be impossible to perform because of the relative rarity of the condition and the ethical ramifications of retaining neural compression in symptomatic patients.

Double crush syndrome summary

Double crush syndrome was initially described as two compressive lesions along the course of a single peripheral nerve leading to symptomatic pathology; however, this narrow definition is controversial and incomplete 25. A complete understanding of the double crush syndrome disease process remains elusive, although continuing research has broadened our knowledge of this intriguing pathologic process. Current understanding of this phenomenon takes into account systemic and vascular pathologic factors as contributing components to compressive pathology. double crush syndrome is a clinical entity that physicians should be aware of when evaluating patients with combined symptoms of not only proximal and distal nerve compression but also systemic disease and polyneuropathy. A combination of patient history, physical examination findings, selective radiographic imaging, and electromyography should be used to diagnosis double crush syndrome. Management should focus on accurate diagnosis and treatment of all contributing pathology.

References- Kane PM, Daniels AH, Akelman E. Double Crush Syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015 Sep;23(9):558-62. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00176

- Katsuura Y, Yao K, Chang E, Kadrie TA, Dorizas JA. Shoulder Double Crush Syndrome: A Retrospective Study of Patients With Concomitant Suprascapular Neuropathy and Cervical Radiculopathy. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Jun 22;13:1179544120921854. doi: 10.1177/1179544120921854

- Lee SU, Kim MW, Kim JM. Ultrasound Diagnosis of Double Crush Syndrome of the Ulnar Nerve by the Anconeus Epitrochlearis and a Ganglion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016 Jan;59(1):75-7. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.1.75

- Upton AR, McComas AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973 Aug 18;2(7825):359-62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93196-6

- Baba H, Maezawa Y, Uchida K, Furusawa N, Wada M, Imura S, Kawahara N, Tomita K. Cervical myeloradiculopathy with entrapment neuropathy: a study based on the double-crush concept. Spinal Cord. 1998 Jun;36(6):399-404. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100539

- Baba M, Fowler CJ, Jacobs JM, Gilliatt RW. Changes in peripheral nerve fibres distal to a constriction. J Neurol Sci. 1982 May;54(2):197-208. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(82)90182-4

- Nemoto K, Matsumoto N, Tazaki K, Horiuchi Y, Uchinishi K, Mori Y. An experimental study on the “double crush” hypothesis. J Hand Surg Am. 1987 Jul;12(4):552-9. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80207-1. Erratum in: J Hand Surg [Am] 1987 Nov;12(6):1011.

- Morgan G, Wilbourn AJ. Cervical radiculopathy and coexisting distal entrapment neuropathies: double-crush syndromes? Neurology. 1998 Jan;50(1):78-83. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.78

- Hebl JR, Horlocker TT, Pritchard DJ. Diffuse brachial plexopathy after interscalene blockade in a patient receiving cisplatin chemotherapy: the pharmacologic double crush syndrome. Anesth Analg. 2001 Jan;92(1):249-51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00049

- Schmid AB, Coppieters MW. The double crush syndrome revisited–a Delphi study to reveal current expert views on mechanisms underlying dual nerve disorders. Man Ther. 2011 Dec;16(6):557-62. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.05.005

- Richardson JK, Forman GM, Riley B. An electrophysiological exploration of the double crush hypothesis. Muscle Nerve. 1999 Jan;22(1):71-7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199901)22:1<71::aid-mus11>3.0.co;2-s

- Flak M, Durmala J, Czernicki K, Dobosiewicz K. Double crush syndrome evaluation in the median nerve in clinical, radiological and electrophysiological examination. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;123:435-41

- Osterman AL. The double crush syndrome. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988 Jan;19(1):147-55.

- Hurst LC, Weissberg D, Carroll RE. The relationship of the double crush to carpal tunnel syndrome (an analysis of 1,000 cases of carpal tunnel syndrome). J Hand Surg Br. 1985 Jun;10(2):202-4. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(85)90018-x

- Massey EW, Riley TL, Pleet AB. Coexistent carpal tunnel syndrome and cervical radiculopathy (double crush syndrome). South Med J. 1981 Aug;74(8):957-9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198108000-00018

- Molinari WJ 3rd, Elfar JC. The double crush syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2013 Apr;38(4):799-801; quiz 801. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.12.038

- Lo SF, Chou LW, Meng NH, Chen FF, Juan TT, Ho WC, Chiang CF. Clinical characteristics and electrodiagnostic features in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome, double crush syndrome, and cervical radiculopathy. Rheumatol Int. 2012 May;32(5):1257-63. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1746-1

- Golovchinsky, V. (2000). Double-Crush Syndrome in Upper Limbs. In: Double-Crush Syndrome. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4419-7_3

- Golovchinsky, V. (2000). Double-Crush Syndrome in Lower Limbs. In: Double-Crush Syndrome. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4419-7_4

- Abdalbary SA, Abdel-Wahed M, Amr S, Mahmoud M, El-Shaarawy EAA, Salaheldin S, Fares A. The Myth of Median Nerve in Forearm and Its Role in Double Crush Syndrome: A Cadaveric Study. Front Surg. 2021 Sep 21;8:648779. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.648779

- Kwon HK, Hwang M, Yoon DW. Frequency and severity of carpal tunnel syndrome according to level of cervical radiculopathy: double crush syndrome? Clin Neurophysiol. 2006 Jun;117(6):1256-9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.02.013

- Bland JD. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2007 Aug;36(2):167-71. doi: 10.1002/mus.20802

- Baba H, Maezawa Y, Uchida K, Furusawa N, Wada M, Imura S, Kawahara N, Tomita K. Cervical myeloradiculopathy with entrapment neuropathy: a study based on the double-crush concept. Spinal Cord. 1998 Jun;36(6):399-404. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.310053

- Galarza M, Gazzeri R, Gazzeri G, Zuccarello M, Taha J. Cubital tunnel surgery in patients with cervical radiculopathy: double crush syndrome? Neurosurg Rev. 2009 Oct;32(4):471-8. doi: 10.1007/s10143-009-0219-z

- Kane, Patrick M. MD; Daniels, Alan H. MD; Akelman, Edward MD. Double Crush Syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: September 2015 – Volume 23 – Issue 9 – p 558-562 doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00176

- Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Chronic nerve compression model for the double crush hypothesis. Ann Plast Surg. 1991 Mar;26(3):259-64. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199103000-00008

- Double-crush syndrome: A critical analysis. Asa J. Wilbourn, Roger W. Gilliatt. Neurology Jul 1997, 49 (1) 21-29; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.49.1.21

- Kwon HK, Hwang M, Yoon DW: Frequency and severity of carpal tunnel syndrome according to level of cervical radiculopathy: Double crush syndrome? Clin Neurophysiol 2006;117(6):1256–1259.

- Dahlin LB. Aspects on pathophysiology of nerve entrapments and nerve compression injuries. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991 Jan;2(1):21-9.

- Tang DT, Barbour JR, Davidge KM, Yee A, Mackinnon SE. Nerve entrapment: update. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Jan;135(1):199e-215e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000828

- Mackinnon SE. Double and multiple “crush” syndromes. Double and multiple entrapment neuropathies. Hand Clin. 1992 May;8(2):369-90.

- Lundborg G, Dahlin LB. The pathophysiology of nerve compression. Hand Clin. 1992 May;8(2):215-27.

- Giannoudis PV, Da Costa AA, Raman R, Mohamed AK, Smith RM: Double-crush syndrome after acetabular fractures: A sign of poor prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87(3):401–407.

- Sunderland S: The relative susceptibility to injury of the medial and lateral popliteal divisions of the sciatic nerve. Br J Surg 1953;41(167):300–302.

- Fassler PR, Swiontkowski MF, Kilroy AW, Routt ML Jr: Injury of the sciatic nerve associated with acetabular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75(8):1157–1166.

- Golovchinsky V: Double crush syndrome in lower extremities. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998;38(2):115–120.

- Augustijn P, Vanneste J: The tarsal tunnel syndrome after a proximal lesion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55(1):65–67.

- Atroshi, I. , Gummesson, C. , Johnsson, R. , Ornstein, E. , Ranstam, J. & Rosen, I. (1999). Prevalence of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome in a General Population. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 282 (2), 153-158. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.2.153

- Moghtaderi A, Izadi S. Double crush syndrome: an analysis of age, gender and body mass index. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008 Jan;110(1):25-9. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.08.013

- Baba M, Ozaki I, Watahiki Y, Kudo M, Takebe K, Matsunaga M. Focal conduction delay at the carpal tunnel and the cubital fossa in diabetic polyneuropathy. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1987 Mar;27(2):119-23.

- Osterman AL: The double crush syndrome. Orthop Clin North Am 1988;19(1):147–155.

- Lo SF, Chou LW, Meng NH, et al.: Clinical characteristics and electrodiagnostic features in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome, double crush syndrome, and cervical radiculopathy. Rheumatol Int 2012;32(5):1257–1263.

- Friedenberg ZB, Miller WT: Degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1963;45:1171–1178.

- Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, Dina TS, Mark AS, Wiesel S: Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects: A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72(8):1178–1184.

- Akyuz M, Yalcin E, Selcuk B, Onder B, Ozçakar L: Electromyography and ultrasonography in the diagnosis of a rare double-crush ulnar nerve injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92(11):1914–1916.

- Abe M, Ichinohe K, Nishida J. Diagnosis, treatment, and complications of thoracic outlet syndrome. J Orthop Sci. 1999;4(1):66-9. doi: 10.1007/s007760050075