Dravet syndrome

Dravet syndrome previously known as severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI), is a rare severe form of epilepsy that is part of a group of diseases known as SCN1A-related seizure disorders. Dravet syndrome affects 1:15,700 individuals and appears during the first year of life as frequent fever-related (febrile) seizures 1. Children with Dravet syndrome initially show focal (confined to one area) or generalized (throughout the brain) convulsive seizures that start before 15 months of age (often before age one). These initial seizures are often prolonged and involve half of the body, with subsequent seizures that may switch to the other side of the body. These initial seizures are frequently provoked by seizures or exposure to increased temperatures (febrile seizures) or temperature changes, such as getting out of a bath. Other seizure types emerge after 12 months of age and can be quite varied. As the condition progresses, other types of seizures typically occur, including myoclonus and status epilepticus 1. Status epilepticus – a state of continuous seizure requiring emergency medical care – may occur frequently in these children, particularly in the first five years of life.

Dravet syndrome affects an estimated 1:15,700 individuals in the U.S., or 0.0064% of the population 2. Approximately 80-90% of those, or 1:20,900 individuals, have both an SCN1A mutation and a clinical diagnosis of Dravet syndrome. This represents an estimated 0.17% of all epilepsies.

Children with Dravet syndrome typically have normal development in the first few years of life. As seizures increase, the pace of acquiring skills slows and children start to lag in development behind their peers. Other symptoms can begin throughout childhood with changes in eating, appetite, balance, and a crouched gait (walking). Intellectual development begins to deteriorate around age 2, and affected individuals often have a lack of coordination, poor development of language, hyperactivity, and difficulty relating to others 3.

Common issues associated with Dravet syndrome include:

- Prolonged seizures

- Frequent seizures

- Behavioral and developmental delays

- Movement and balance issues

- Orthopedic conditions

- Delayed language and speech issues

- Growth and nutrition issues

- Sleeping difficulties

- Chronic infections

- Sensory integration disorders

- Dysautonomia or disruptions of the autonomic nervous system which can lead to difficulty regulating body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and other issues

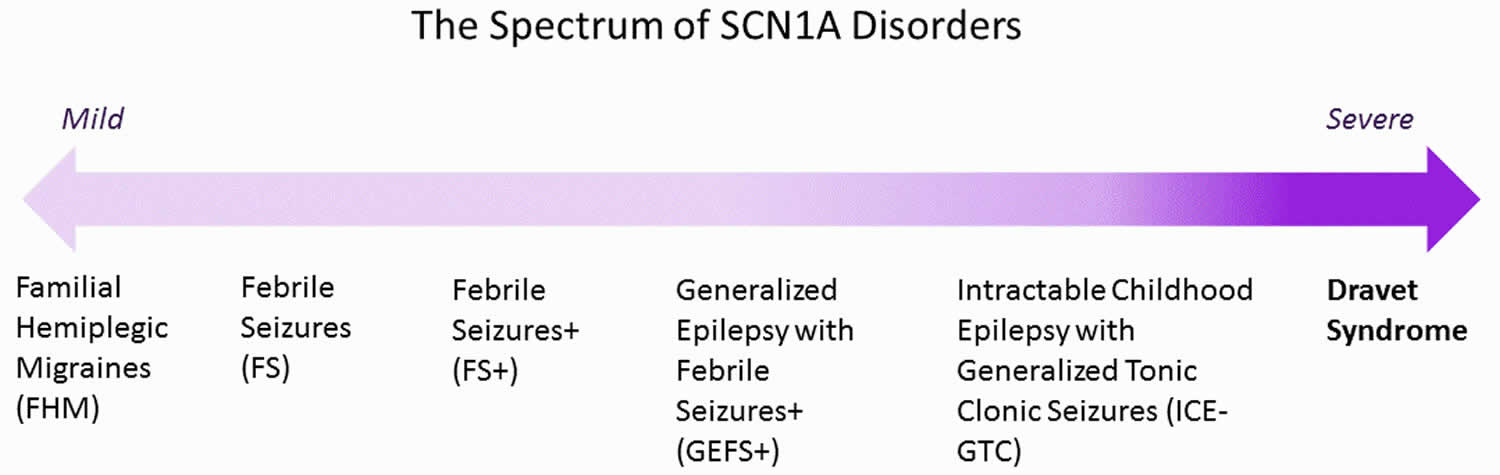

Dravet syndrome lies at the severe end of the spectrum of SCN1A-related disorders but can be associated with other mutations as well 4. Around 85% of Dravet syndrome cases are due to a mutation in the SCN1A gene (a gene that encodes as a sodium channel, a part of the cell membrane involved in nervous system function), which is required for the proper function of brain cells 5. Borderline severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEB) and another type of infant-onset epilepsy called generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) but which is much less severe, are caused by defects in the same gene. A family history of either epilepsy or febrile seizures exists in 15 percent to 25 percent of cases 3. In about 10% of cases the cause is unknown but other genes are likely the cause 6.

Dravet syndrome is a lifelong condition. Current treatment options are limited and the main goal of treatment is to reduce seizures frequency and prevent status epilepticus 6. Seizures in Dravet syndrome are difficult to control, but can be reduced by anticonvulsant drugs. A ketogenic diet, high in fats and low in carbohydrates, also may be beneficial. Some anticonvulsant medications that bind to sodium channels (such as oxcarbazepine, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and lamotrigine) should not be used on a daily basis as they may exacerbate seizures.

In June 2018 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved cannabidiol (Epidolex, derived from marijuana) for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome for people ages 2 and older. The drug contains only small amount of the psychoactive element in marijuana and does not induce euphoria associated with the drug. This is the first FDA-approved drug for Dravet syndrome.

Moderate to severe cognitive impairment and intractable epilepsy into adulthood is common 6. The constant care required for someone suffering from Dravet syndrome can severely impact the patient’s and the family’s quality of life. Patients with Dravet syndrome face a 15-20% mortality rate due to SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy), prolonged seizures, seizure-related accidents such as drowning, and infections 7. Research for a cure offers patients and families hope for a better quality of life for their loved ones.

Figure 1. SCN1A Dravet syndrome

Dravet syndrome causes

Dravet syndrome is associated with a mutation in the SCN1A gene in 80-90% of cases (Rosander 2015). Improved genetic testing including duplication, deletion, and mosaicism identification continues to increase this percentage 8. Missense (40%), nonsense (20%), frameshift (20%), duplications/deletions (7%), and splice site mutations (10%) have all been associated with Dravet syndrome. A description of different types of gene mutations is available here: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/mutationsanddisorders/possiblemutations

Milder presentations (phenotypes) of conditions associated with SCN1A are more often associated with missense mutations, but neither the type of mutation nor the location on the gene corresponds to clinical severity of Dravet syndrome.

90% of mutations appear to be de novo, or new to the child and not inherited from a parent. In the documented cases of inherited SCN1A mutations, the parent has a milder form of epilepsy or no neurological symptoms, whereas the child presents with Dravet syndrome. Improved testing has discovered mosaic mutations in parents who previously tested negative for an SCN1A mutation. Mosaicism is a condition in which some cells within a person differ genetically from other cells within that same person. This can happen shortly after fertilization, when a single cell within a cluster of cells undergoes a spontaneous mutation. Only the cells descending from that mutated cell will carry the mutation: The non-mutated cells will give rise to healthy cells, and thus the developed individual may have slightly different makeup of his/her cells.

Risk of recurrence is 50% in families with inherited SCN1A mutations. Because of the identification of mosaicism and the possibility of mutations in egg or sperm cells (germ-line mutations), the risk of recurrence for even apparently de novo mutations is elevated above that of the general public, and thus genetic counseling is recommended.

Other genes have been associated with Dravet syndrome including SCN2A, SCN8A, GABRA1, GABARG2, PCDH19, STXBP1, and SCN1B, but the clinical presentation in these cases is often somewhat atypical of Dravet syndrome 9.

Dravet syndrome inheritance pattern

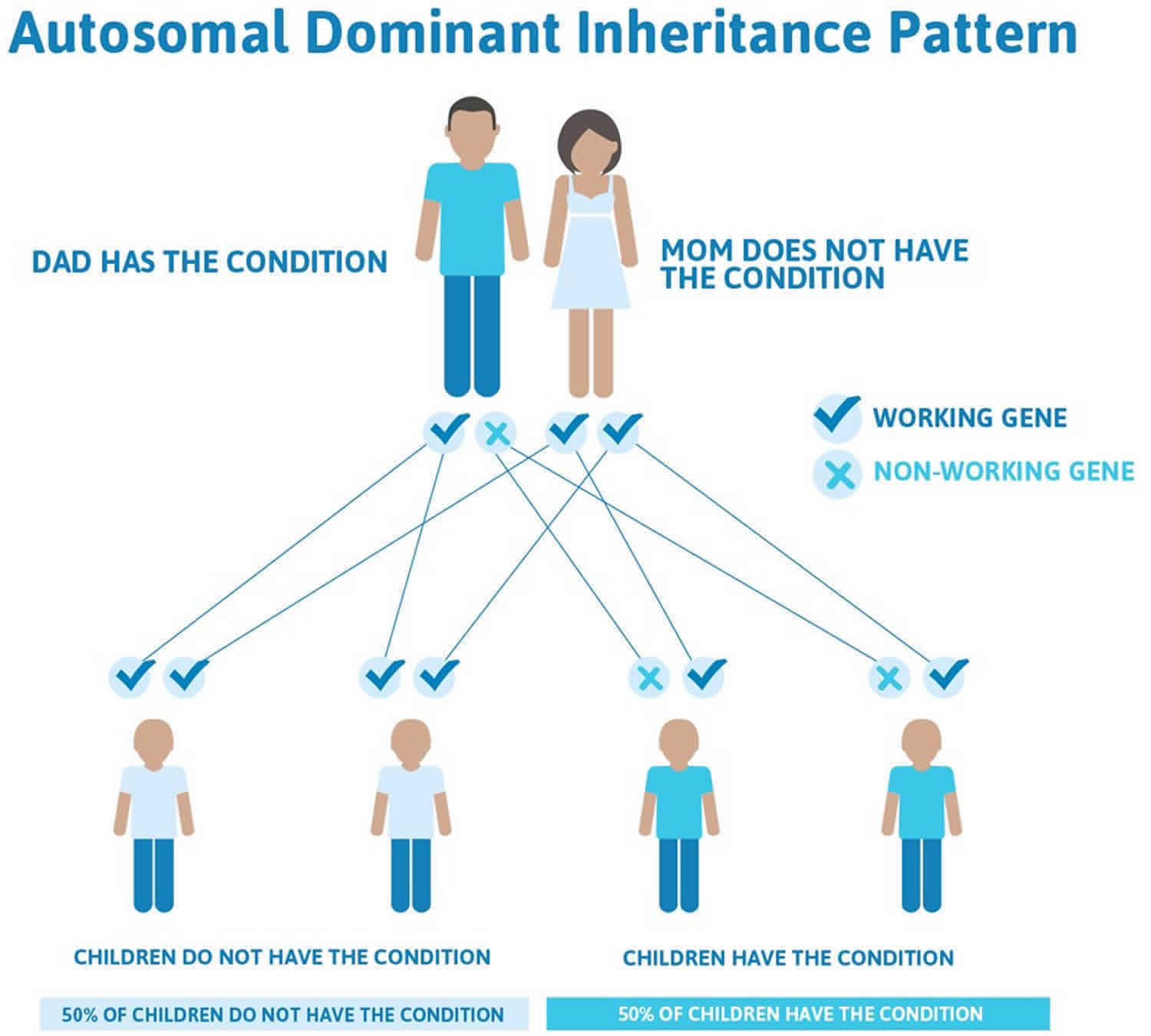

In families with a known SCN1A mutation, inheritance is autosomal dominant and genetic counseling is possible, even though the phenotypic range in families can be wide. In cases with de novo mutations, counseling may help with the decision making process for future children.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

There are cases of autosomal dominant gene changes, or mutations, where no one in the family has it before and it appears to be a new thing in the family. This is called a de novo mutation. For the individual with the condition, the chance of their children inheriting it will be 50%. However, other family members are generally not likely to be at increased risk.

Figure 2 illustrates autosomal dominant inheritance. The example below shows what happens when dad has the condition, but the chances of having a child with the condition would be the same if mom had the condition.

Figure 2. Dravet syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Dravet syndrome symptoms

The average age at seizure onset is 5.2 months, with a range of 1-18 months, but most often under 12 months 10. The first seizure is often prolonged, either of the generalized tonic clonic or hemiclonic variation, and may or may not be associated with fever. Shorter seizures may also occur. Hyperthermia, or overheating, is a common seizure trigger in Dravet syndrome, and patients display heightened sensitivity to warm baths, fevers, exertion, and other forms of temperature elevation 9.

Myoclonic seizures, when they occur, are typically seen by age 2 years but are not required for diagnosis. Non-convulsive status (obtundation status) focal seizures with impaired awareness and atypical absence seizures generally occur after 2 years. Typical absence seizures and epileptic spasms are unusual. The initial EEG, CT, MRI, and spinal tap are often normal, although background slowing may be evident if performed after a seizure. Subsequent EEGs may show diffuse slowing and/or generalized discharges while other imaging remains normal. MRI may show mild generalized atrophy or hippocampal sclerosis later in life. Development is usually on track during the first year but delay often appears in the 2nd and 3rd years of life and is usually evident by age 18-60 months 9.

In older children and adults, seizures persist, though status epilepticus becomes less frequent with time. Developmental delay, speech impairment, crouched gait, hypotonia, lack of coordination, and impaired dexterity are evident.

Any patient with a clinical history suggestive of Dravet syndrome should undergo genetic testing for SCN1A and/or other epilepsy-related genes. The presence of an SCN1A mutation can help confirm diagnosis, but the presence of a mutation alone is not sufficient for diagnosis, nor does the absence of a mutation exclude diagnosis. Most experts believe an infant with two or more prolonged generalized tonic clonic or hemiclonic seizures with or without fever before age 12 months should undergo genetic testing 9.

Dravet syndrome diagnosis

Dravet syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. Presentation is uniquely characteristic and, according to the 2017 consensus of North American neurologists with expertise in Dravet syndrome , includes:

- Typical onset between 1 and 18 months, most often <12 months, average 5.2 months 9

- Recurrent generalized tonic-clonic or hemiconvulsive seizures, often prolonged but may be short

- Myoclonic seizures appearing by age 2 years, followed by obtundation status, focal seizures with impaired awareness, and atypical absence seizures.

- Hyperthermia triggers seizures in most patients (due to illness, vaccination, warm baths, exertion, etc.) Other triggers may include visual patterns or photosensitivity, eating, and bowel movements

- Normal development, neurological exam, MRI, and normal or nonspecific EEG findings at onset

In older children and adults:

- Persisting seizures, which may or may not be prolonged. Status epilepticus becomes less frequent with time and may not be apparent by young adulthood

- Hyperthermia as a seizure trigger may decline as the patient ages

- Seizure exacerbation with the use of sodium channel agents

- Intellectual disability evident by 18-60 months

- Crouched gait, hypotonia, incoordination, and impaired dexterity

- MRI may be normal or show mild generalized atrophy and/or hippocampal sclerosis

- EEG may show diffuse background slowing with multifocal and/or generalized interictal discharges.

Genetic testing

Because many of these criteria are not apparent in the first year of life and infants with Dravet syndrome initially experience typical development, the study determined genetic testing via an epilepsy panel should be considered in patients exhibiting any of the following:

- 2 or more prolonged seizures by 1 year of age

- 1 prolonged seizure and any hemi-clonic (sustained, rhythmic jerking of one side of the body) seizure by 1 year of age

- 2 seizures of any length that seem to affect alternating sides of the body

- History of seizures prior to 18 months of age and later emergence of myoclonic and/or absence seizures

If you suspect your loved one might have Dravet syndrome, ask your neurologist about testing, which is available through your doctor or commercially. An epilepsy panel will test for SCN1A as well as many other genes commonly associated with epilepsy. Following testing, consultation with a genetic counselor is recommended.

Dravet syndrome treatment

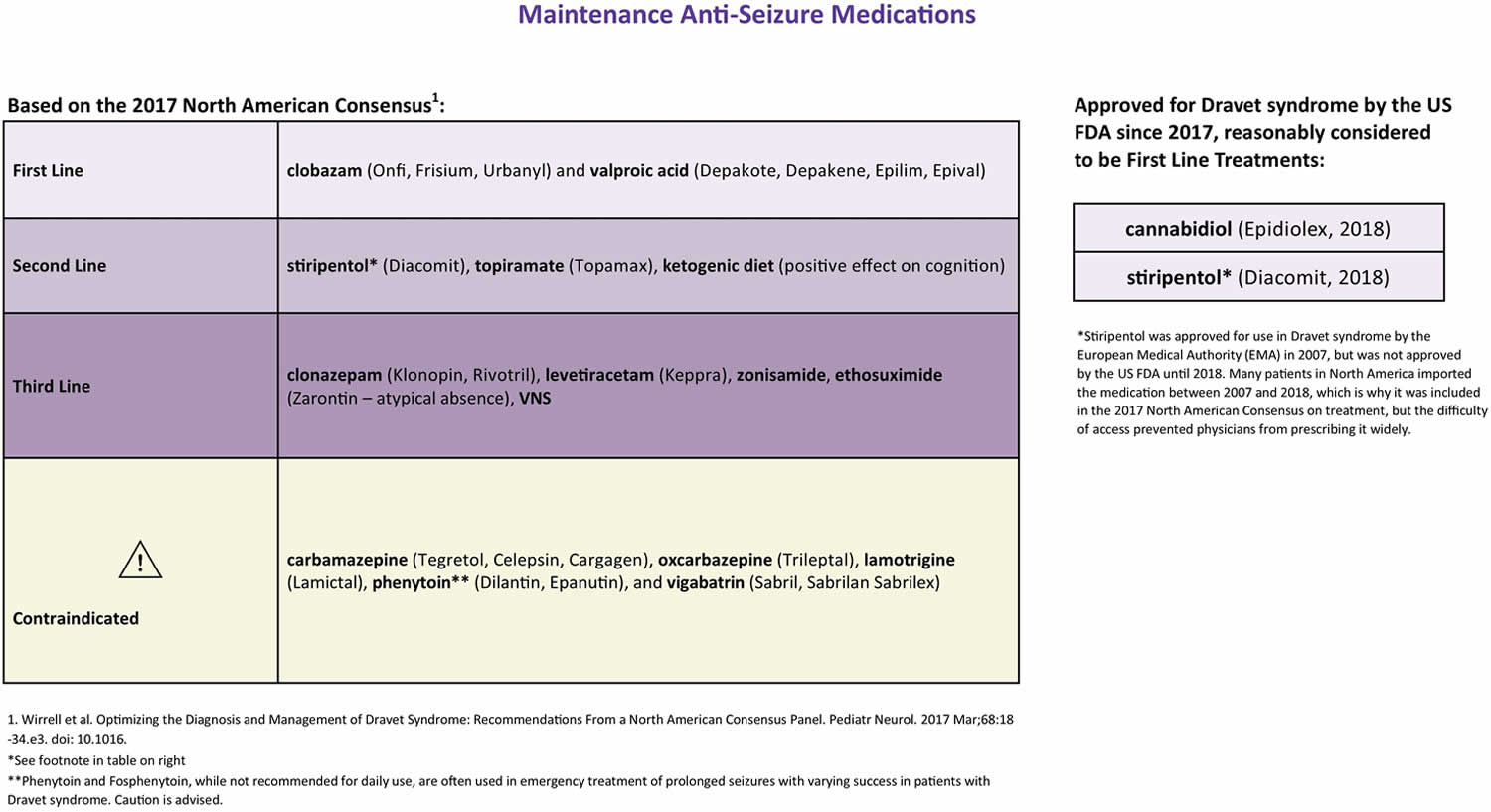

Dravet syndrome is a spectrum disorder, meaning patients present with a wide range of severity and seizure types, and no two patients respond to treatment the same way. What helps one may not help another, and vice versa. There is no cure for Dravet syndrome and most treatments aim to reduce seizures. Several medications have proven beneficial in many patients (sometimes called “first line treatments”) and some medications have been known to exacerbate seizures in many patients (called “contraindicated” medications) due to their effects on the sodium ion channel. In 2018, two medications were granted US FDA approval for the treatment of Dravet syndrome due to positive results in clinical trials: Epidiolex, which is a cannabidiol (CBD) extract, and Diacomit (stiripentol).

First line anti-seizure medications include clobazam (Onfi, Frisium) and valproic acid (Depakote, Depakene). Second line treatments include stiripentol (Diacomit), topiramate (Topamax), and the ketogenic diet. Variations of the ketogenic diet including the Modified Atkins Diet may also be beneficial in Dravet syndrome. Third line treatments include clonazepam (Klonopin), levetiracetam (Keppra), zonisamide (Zonegran), ethosuximide (Zarontin), and vagal nerve stimulator 9.

In 2018, Epidiolex (cannabidiol or CBD) was approved to treat seizures associated with Dravet syndrome in patients two years of age and older. This is the first FDA-approved product to treat Dravet syndrome. Epidiolex is manufactured by GW Research Ltd.

Also in 2018, Dicomit (stiripentol) was approved for the treatment of seizures associated with Dravet syndrome in patients two years of age and older who are also taking clobazam. Diacomit is manufactured by Biocodex.

Medications that SHOULD NOT be used in Dravet syndrome include sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine (Tegretol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), lamotrigine (Lamictal), vigabatrin (Sabril), rufinamide (Banzel), phenytoin (Dilantin), fosphenytoin (Cerebyx, Prodilantin). Note that phenytoin and fosphenytoin should be avoided as a daily medication but their efficacy in emergency treatment of status epilepticus is unclear.

Status epilepticus is frequent in Dravet syndrome and caregivers should be trained to administer at-home medications to stop prolonged seizures. Rectal diazepam and buccal (by mouth) or intranasal (via the nose) midazolam are frequently used.

Rescue medications

Many patients with Dravet syndrome experience prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) that require emergency intervention. For this reason, your neurologist may prescribe a rescue medication, typically a benzodiazepine, that is given during the seizure to help stop it.

Rescue medications include:

- Clonazepam (Klonopin)

- Diazepam (Diastat)

- Lorazepam (Ativan)

- Midazolam (Versed)

A current U.S-wide study is enrolling patients who are witnessed by medical professionals to seize for longer than 5 minutes. After appropriate benzodiazepines have been administered, patients may be enrolled without consent, and given one of three rescue medications: valproic acid, levetiracetam, or fosphenytoin. The study is double-blind, meaning no one (including the treating physician) knows which treatment is administered. Because fosphenytoin is contraindicated in Dravet syndrome, this could result in worsening of the condition in patients with Dravet syndrome, and the Dravet Syndrome Foundation recommends you discuss the study and measures you can take to opt out with your treating neurologist.

Alternative treatments

Other treatments and therapies have shown positive results in the overall care and management of Dravet syndrome in some patients, even though they have not been fully studied. These include IVIG (Intravenous Immunoglobulin) Therapy, various dietary interventions, and VNS (Vagus Nerve Stimulation) Therapy.

Dravet syndrome prognosis

People with Dravet syndrome require constant care, and the condition can severely impact the patient’s and family’s quality of life 11. About 10-20% of people with Dravet syndrome are estimated to pass away before adulthood, with most premature deaths occurring before 10 years of age 12. The average age of death is about 8 years and ranges from infancy to 18 years of age. The most common cause of death is sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) 12.

SUDEP was a likely cause of death in nearly half of the people (87 out of 177 or 49% of deaths). Other causes of death included 13:

- Status epilepticus (32% of deaths)

- Drowning or accidents (8% of deaths)

- Infection (5% of deaths)

- Other or unknown cause (6% of deaths)

- Death occurred before the age of 10 years in 3 out of 4 people (73%).

- Dravet Syndrome Information Page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Dravet-Syndrome-Information-Page

- Wu YW, Sullivan J, McDaniel SS, Meisler MH, Walsh EM, Li SX, Kuzniewicz MW. Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population. Pediatrics. 2015 Nov;136(5):e1310-5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1807.

- Dravet Syndrome. https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/types-epilepsy-syndromes/dravet-syndrome

- Ian O Miller, MD, Marcio A Sotero de Menezes, MD. SCN1A-Related Seizure Disorders. Gene Reviews. Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. Seattle (WA):University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2016.

- Wu, E., et. al. (2015). Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population. Pediatrics 136(5): 1310-e1315. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1807. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4621800

- Dravet syndrome. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=EN&Expert=33069

- Cooper, M.S., et. al. (2016). Mortality in Dravet Syndrome. Epilepsy Research Oct 26;128:42-47. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.10.006

- Djémié T, Weckhuysen S, von Spiczak S, et al. Pitfalls in genetic testing: the story of missed SCN1A mutations. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016;4(4):457–464. Published 2016 Apr 14. doi:10.1002/mgg3.217 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4947864

- Wirrell EC, Laux L, Donner E, Jette N, Knupp K, Meskis MA, Miller I, Sullivan J, Welborn M, Berg AT. Optimizing the Diagnosis and Management of Dravet Syndrome: Recommendations From a North American Consensus Panel. Pediatr Neurol. 2017 Mar;68:18-34.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.01.025

- Cetica V, Chiari S, Mei D, Parrini E, Grisotto L, Marini C, Pucatti D, Ferrari A, Sicca F, Specchio N, Trivisano M, Battaglia D, Contaldo I, Zamponi N, Petrelli C, Granata T, Ragona F, Avanzini G, Guerrini R. Clinical and genetic factors predicting Dravet syndrome in infants with SCN1A mutations. Neurology. 2017 Mar 14;88(11):1037-1044. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003716

- WHAT IS DRAVET SYNDROME? https://www.dravetfoundation.org/what-is-dravet-syndrome

- Shmuely S, Sisodiya SM, Gunning WB, Sander JW, Thijs RD. Mortality in Dravet syndrome: A review. Epilepsy Behav. November 2016; 64(PtA):69-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27732919

- Mortality in Dravet syndrome: A review. Epilepsy & Behavior Volume 64, Part A, November 2016, Pages 69-74 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.09.007