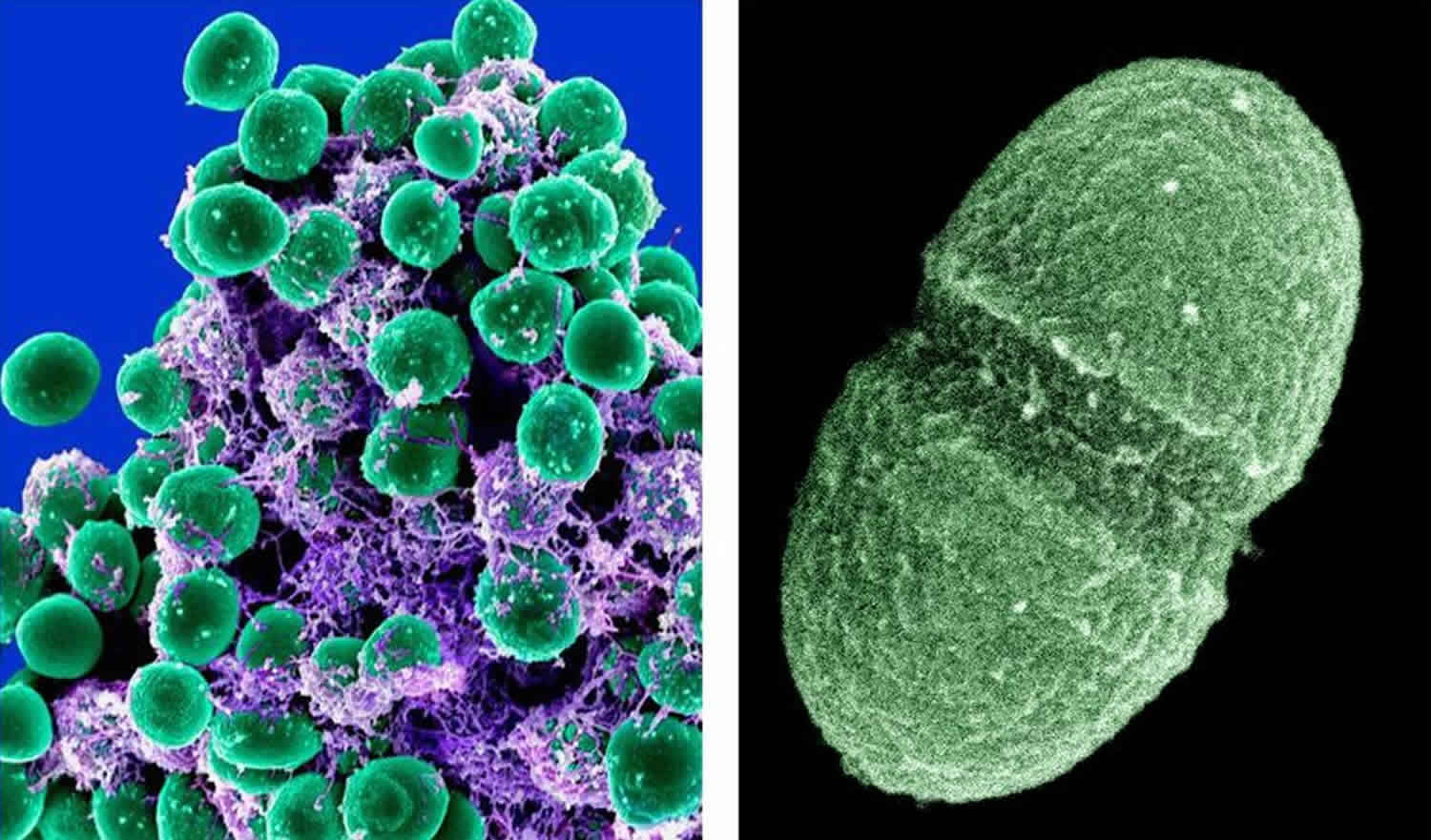

Enterococcus faecalis

Enterococcus faecalis are Gram-positive non-spore-forming bacteria that typically inhabit the gastrointestinal tracts of nearly all land animals, including humans 1. Enterococcus faecalis is a gut commensal, which is occasionally found in the mouth and vaginal tract, and does not usually cause clinical problems 2. However, it can spread to other areas of the body and cause life-threatening infections, such as septicemia, endocarditis, or meningitis, in immunocompromised hosts 2, most often among antibiotic-treated hospitalized patients with perturbed intestinal microbiota 1.

According to the National Healthcare Safety Network, enterococci species ranked as the second overall healthcare-associated infection between 2011 and 2014. In particular, Enterococcus faecalis was a cause in 7.4% of cases 3. Furthermore, Enterococci species were found to be the number one isolate for central line-associated bloodstream infections, number three for catheter-associated urinary tract infection, number eleven for ventilator-associated pneumonia and number two for surgical site infections 3. More than 90% of the bacterial isolates frequently recovered from clinical specimens (blood, and other infectious site samples) are Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium 4. Life-threatening infections generally linked to Enterococcus faecalis include endocarditis, bacteremia, urinary tract infections, meningitis, and root canal infections. While the majority of Enterococcus isolates are Enterococcus faecalis, the majority of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus isolates are Enterococcus faecium. From 2011 to 2014 the resistance of Enterococcus faecalis to vancomycin was as high as 83.8 % of isolates for central line-associated bloodstream infections and 86.2 % for catheter-associated urinary tract infection. In 2013 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) categorized vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus as a “serious threat,” suggesting the need for increased monitoring and prevention activities.

There are many risk factors for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization and subsequent infections. The most commonly observed risk factor is previous antimicrobial therapy. This mechanism likely is due to alteration in bowel flora. Furthermore, patients at increased risk are those with severe underlying illnesses or immunosuppression. This also includes patients with a long hospital stay, admission to long-term care facilities, extended use of antibiotics, and proximity to other patients with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus 5.

Enterococcus faecalis infection

Enterococcus can cause a wide range of clinical diseases. The most common clinical presentation is bacteriuria (bacteria in urine), though it is becoming increasingly clear that many of these cases are due to colonization rather than infection. Other frequent causes of infection are bacteremia (bacteria in bloodstream) without endocarditis, followed by endocarditis.

Urinary tract infection

Enterococcus is frequently cited as one of the three most likely causes of both uncomplicated and complicated urinary tract infection (UTI), especially healthcare-associated urinary tract infections. Of these, the vast majority is enterococcus faecalis, though the majority of vancomycin-resistant isolates are enterococcus faecium. It is usually associated with indwelling urinary catheters and instrumentation. The severity of the disease can range from uncomplicated cystitis to complicated cystitis to pyelonephritis, perinephric abscess, or prostatitis. There is an increasing awareness that many reported “urinary tract infections” are, in fact, colonization. Asymptomatic pyuria and bacteriuria should not be treated unless the patient is exhibiting signs and/or symptoms of a urinary tract infection or sepsis.

Intra-abdominal and pelvic infections

As commensals, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus is commonly isolated from intra-abdominal and pelvic infections. The usual infections include abscesses, wounds, or peritonitis. Often they are part of a polymicrobial infection with other gram-negative or anaerobic organisms. Nonetheless, intra-abdominal and pelvic abscesses are commonly associated with enterococcal bacteremia prompting antibiotic coverage of Enterococcus.

Bacteremia

Bacteremia is a common and life-threatening manifestation of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Nosocomial bacteremic infections are regularly acquired due to intravascular catheters or urinary catheters. In the community, bacteremia is commonly due to translocation from the gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary tract. Enterococcus faecium in the bloodstream is associated with increased mortality likely due to the higher levels of resistance.

Infective endocarditis

Enterococcus are the second most common cause of infective endocarditis. Common sources are central lines, gastrointestinal tract or genitourinary tract after manipulation, damaged mitral or aortic valve infections, or liver transplantation. Community-acquired endocarditis can occur, and it is usually due to enterococcus faecalis in patients with no risk factors. Clinically, they present subacutely with fevers and constitutional symptoms. Typical signs of infection include fevers or a new murmur. Typical stigmata of endocarditis such as petechiae, Osler nodes, and Roth spots are rare and, as with other etiologies, typically occur with subacute infection rather than acute infection.

Uncommon sites of infection

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus is an uncommon cause of central nervous system (CNS) infections. However, when it does occur, the majority are caused by enterococcus faecium over enterococcus faecalis. Infection usually is associated with neurosurgical intervention such as shunts. Like most central nervous system infections, common presentations include altered mental status and fevers. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus also is found in skin infections as a part of a microbial infection. They can be found in decubitis ulcers, osteomyelitis, and soft tissue abscesses. Finally, pneumonia secondary to enterococci is very rare. When it does occur, it is usually seen as ventilator-associated pneumonia in severely debilitated and immunocompromised patients who have received broad-spectrum antibiotics in the past.

Enterococcus faecalis treatment

The vast majority of enterococcal infections are due to enterococcus faecalis. Enterococcus faecalis tends to be susceptible to beta-lactams and aminoglycosides. Vancomycin resistance is more frequent in undifferentiated enterococcus faecalis than resistance to aminopenicillins, stressing that beta-lactams should remain the first choice in most infections before culture data. Conversely, most strains of enterococcus faecium are highly resistant to beta-lactams and aminoglycosides. In general, if vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus is highly resistant to other antimicrobial therapies; the two major treatments are linezolid and daptomycin. A meta-analysis of these two therapies has shown that the overall mortality, clinical cure, microbiological cure, and relapse rate were not significantly different. Importantly, the most common genotypic causes of vancomycin resistance are VanA and VanB which are inducible resistance genes. As a result, patients with initially vancomycin sensitive isolates that do not respond to treatment should be re-cultured.

If vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus is isolated and highly susceptible, therapy should be narrowed. For urinary tract infections (UTIs), monotherapy with high dose ampicillin, 18 to 30 g/day intravenous (IV), should be started. If the urinary tract infection is uncomplicated but resistant to ampicillin, then nitrofurantoin 100 mg per os (oral) twice a day or fosfomycin 3 g orally single dose are the preferred agents. However, it is important to note that urinary tract infections could be secondary to colonization and removal of the catheter could be therapeutic. For bacteremia, monotherapy with ampicillin often can be used as well. However, this does not provide bactericidal activity, so an aminoglycoside such as gentamycin can usually be added. Ampicillin with ceftriaxone is an alternative regimen as it has similar efficacy to ampicillin and gentamycin but is less nephrotoxic.

If sensitivities are not available, or for high levels of resistance to beta-lactams or aminoglycosides, linezolid, 600 mg oral or IV twice a day, can be used. A synthetic oxazolidinone antibiotic, this is a bacteriostatic drug that binds to the ribosome, preventing peptide bond formation. For endocarditis, linezolid has been shown to be an effective first-line medication, although it is a bacteriostatic drug. Adverse effects, especially after prolonged use, include thrombocytopenia, anemia, peripheral neuropathy, and risk of inducing serotonin syndrome. Alternatives should be considered with patients who regularly take serotonergic medications.

Another alternative is off-label use of high dose daptomycin 8 to 12 mg/kg IV (with renal adjustment) once a day. A lipopeptide antibiotic, it is bactericidal and causes cell membrane depolarization. Importantly, if patients are persistently bacteremic or the minimum inhibitory concentration is high for daptomycin, then combination therapy with ampicillin or ceftaroline can be used. Patients should be evaluated for myopathy, and weekly creatine kinase levels should be obtained. Furthermore, daptomycin is not effective on pulmonary infections as surfactant inactivates it, but this is rarely a concern with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus because enterococcal pneumonia is exceedingly rare.

Tigecycline, a glycylcycline antibiotic, can be used for patients who are intolerant to other agents. It also can be used if other infections are present with the vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus as it has good coverage against gram positives, some gram negatives, and anaerobes. Although it is off-label, it is specifically considered a preferred agent for polymicrobial intraabdominal infections. It should not be used for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus bacteremia as it distributes primarily to tissues and achieves low serum concentrations. Typical dosing is 100 mg IV once followed by 50 mg IV twice a day. Patients should be monitored for major adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting.

Chloramphenicol, at 50 to 100 mg/kg/day divided into doses every 6 hours (4 g/day max dose), has been used successfully to treat vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus bacteremia for many years and has excellent tissue penetration, including the central nervous system (CNS). Due to its high incidence of toxicity and adverse effects, such as aplastic anemia or bone marrow suppression, it should not be used as a first-line agent when other options are available and should generally be initiated in consultation with an infectious-disease specialist. It remains an option in resource-poor environments where modern drugs may not be available.

References- Fiore E, Van Tyne D, Gilmore MS. Pathogenicity of Enterococci. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(4):10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0053-2018. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0053-2018 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6629438

- Bolocan AS, Upadrasta A, Bettio PHA, et al. Evaluation of Phage Therapy in the Context of Enterococcus faecalis and Its Associated Diseases. Viruses. 2019;11(4):366. Published 2019 Apr 20. doi:10.3390/v11040366 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6521178

- Levitus M, Perera TB. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci (VRE) [Updated 2018 Nov 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513233

- Simonsen G.S., Småbrekke L., Monnet D.L., Sørensen T.L., Møller J.K., Kristinsson K.G., Lagerqvist-Widh A., Torell E., Digranes A., Harthug S., et al. Prevalence of resistance to ampicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolates from clinical specimens and use of antimicrobials in five Nordic hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;51:323–331. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg052

- Lee T, Pang S, Abraham S, Coombs GW. Antimicrobial-resistant CC17 Enterococcus faecium: The past, the present and the future. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018 Aug 24;16:36-47.