Enthesitis

Enthesitis also known as an enthesopathy, refers to an inflammation of enthesis, the connective tissue where the ligaments and tendons attach to the bones. The entheses are any point of attachment of skeletal muscles to bone, where recurring stress or inflammatory autoimmune disease can cause inflammation or occasionally fibrosis and calcification. Clinical symptoms of enthesitis include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation. Enthesitis-related arthritis may also involve inflammation in parts of the body other than the joints. Often referred to as spondyloarthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis is more common in boys and usually begins between the ages of 8 and 15. Affected children will often test positive for the HLA-B27 gene. Spondyloarthritis is an umbrella term for inflammatory diseases that involve both the joints and the entheses (the sites where the ligaments and tendons attach to the bones). The most common of these diseases is ankylosing spondylitis. Others include reactive arthritis, plantar fasciitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, Achilles tendinitis and enteropathic arthritis, which is associated with the inflammatory bowel disease.

One of the primary entheses involved in inflammatory autoimmune disease is at the heel. Enthesitis in the Achilles tendon is common in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Heel swelling and inflammation are therefore used to help diagnose certain inflammatory autoimmune diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis.

Enthesitis examples:

- Adhesive capsulitis of shoulder

- Rotator cuff syndrome of shoulder and allied disorders

- Periarthritis of shoulder

- Scapulohumeral fibrositis

- Enthesopathy of elbow region

- Enthesopathy of wrist and carpus

- Bursitis of hand or wrist

- Periarthritis of wrist

- Enthesopathy of hip region

- Bursitis of hip

- Gluteal tendinitis

- Iliac crest spur

- Psoas tendinitis

- Trochanteric tendinitis

- Enthesopathy of knee

- Enthesopathy of ankle and tarsus

- Other peripheral enthesopathies

- Unspecified enthesopathy

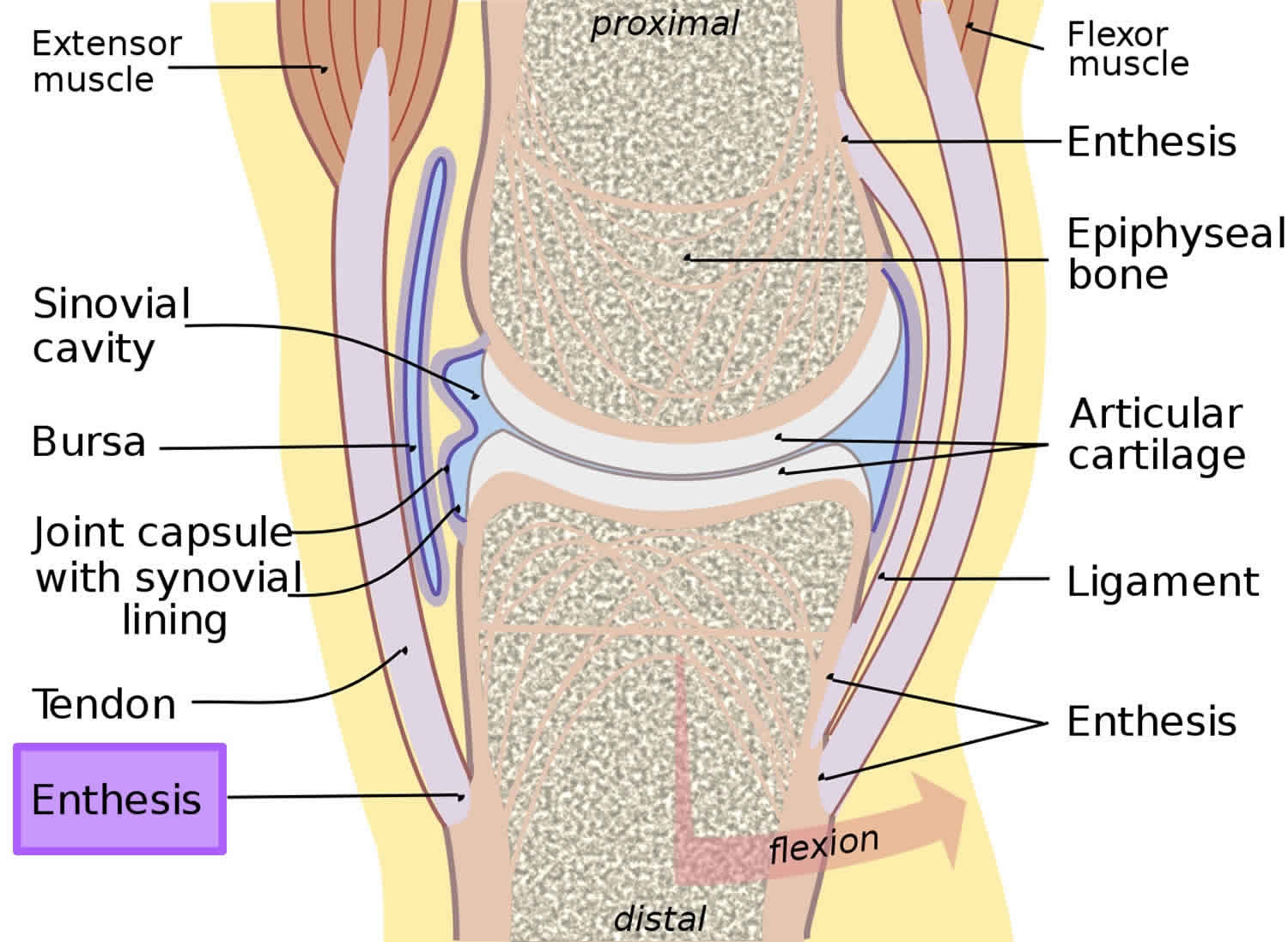

Figure 1. Enthesis

Psoriatic arthritis enthesitis

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of inflammatory arthritis that affects about 30 percent of people with psoriasis. According to the Annals of Rheumatic Disease, between 6 and 42 percent of people who have psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis. The disease usually appears between the ages of 30 and 55 in people who have psoriasis, but it can be diagnosed during childhood. Unlike many autoimmune diseases, men and women are equally at risk for developing this condition. Like psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis is an autoimmune disease, meaning it occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue, in this case the joints and skin. The faulty immune response causes inflammation that triggers joint pain, stiffness and swelling. The inflammation can affect the entire body and may lead to permanent joint and tissue damage if it is not treated early and aggressively.

Most people with psoriatic arthritis have skin symptoms before joint symptoms. However, sometimes the joint pain and stiffness strikes first. In some cases, people get psoriatic arthritis without any skin changes.

Some people have mild, occasional flare-ups. Others may have ongoing inflammation that can cause joint damage if it’s not diagnosed early and treated. Psoriatic arthritis often, but not always, happens to people who also have psoriasis, a skin disease. It often affects large joints in the lower extremities, but may also occur in joints like the fingers, toes, back or pelvis. It usually starts between ages 30 and 50. Men and women are equally at risk. Children with psoriatic arthritis have a higher risk of uveitis, an eye inflammation. Treatments aim to ease pain, protect joints and maintain mobility. Physical activity is also helpful.

The disease may lay dormant in the body until triggered by some outside influence, such as a common throat infection. Another theory suggesting that bacteria on the skin triggers the immune response that leads to joint inflammation has yet to be proven.

Types of psoriatic arthritis

There are five types of psoriatic arthritis:

- Symmetric psoriatic arthritis. This makes up about 50 percent of psoriatic arthritis cases. Symmetric means it affects joints on both sides of the body at the same time. This type of arthritis is similar to rheumatoid arthritis.

- Asymmetric psoriatic arthritis: Often mild, this type of psoriatic arthritis appears in 35 percent of people with the condition. It’s called asymmetric because it doesn’t appear in the same joints on both sides of the body.

- Distal psoriatic arthritis: This type causes inflammation and stiffness near the ends of the fingers and toes, along with changes in toenails and fingernails such as pitting, white spots and lifting from the nail bed.

- Spondylitis: Pain and stiffness in the spine and neck are hallmarks of this form of psoriatic arthritis.

- Arthritis mutilans: Although considered the most severe form of psoriatic arthritis, arthritis mutilans affects only 5 percent of people who have the condition. It causes deformities in the small joints at the ends of the fingers and toes, and can destroy them almost completely.

Psoriatic arthritis enthesitis causes

The cause of psoriatic arthritis is unknown. Experts believe some people may be predisposed to an autoimmune disease like psoriatic arthritis. In fact, studies show a stronger genetic or family link to this particular disease than other autoimmune rheumatic diseases. About 40 percent of people who are diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis have family members affected by the disease.

Not everyone who has psoriasis develops psoriatic arthritis. Psoriasis is not infectious, but the disease might be triggered by a strep throat. In addition to infections, researchers believe psoriatic arthritis also can be triggered by extreme stress or an injury that makes the immune system go into overdrive in people who are genetically more likely to get the disease.

Psoriatic arthritis enthesitis symptoms

People with psoriatic arthritis often develop enthesitis, or tenderness or pain where tendons or ligaments attach to bones. This commonly occurs at the heel (Achilles tendinitis) or the bottom of the foot (plantar fasciitis), but it can also occur in the elbow (tennis elbow). Each of these conditions could just as easily result from sports injuries or overuse as from psoriatic arthritis.

Many people experience frequent periods of increased disease activity and symptoms, called flares, while others have only infrequent flares. This waxing and waning of symptoms is frequently seen with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), as well.

Psoriatic arthritis is closely linked with inflammatory bowel disease, especially the form called Crohn’s disease. It causes diarrhea and other gastrointestinal problems The inflammation that causes psoriatic arthritis may also harm the lungs, causing a condition known as interstitial lung disease that leads to shortness of breath, coughing and fatigue. Chronic inflammation can damage blood vessels, increasing the risk for heart attacks and strokes. People with psoriatic arthritis often develop metabolic syndrome, a group of conditions that include obesity, high blood pressure and poor cholesterol levels. Other problems that can accompany psoriatic arthritis include depression, an increased risk for osteopenia (thinning bones) and osteoporosis, and a higher-than-average risk of developing gout.

Other symptoms of psoriatic arthritis

Symptoms of psoriatic arthritis vary among different people. Many are common to other forms of arthritis, making the disease tricky to diagnose. Here’s a look at the most common symptoms – and the other conditions that share them.

Painful, swollen joints

Psoriatic arthritis typically affects the ankle, knees, fingers, toes and lower back. Pain in the lower back is also a symptom of ankylosing spondylitis, a form of inflammatory arthritis that causes the vertebrae to fuse, or joint together. Also, the joint at the tip of the finger may swell, making it easy to confuse with gout, a form of inflammatory arthritis that typically affects only one joint.

Stiffness

Joints tend to be stiff either first thing in the morning or after a period of rest. However, people with osteoarthritis often have similar stiffness.

Sausage-like fingers or toes

Many people with psoriatic arthritis have dactylitis, a sausage-like swelling along the entire length of their fingers or toes. This symptom is one that helps differentiate psoriatic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in which the swelling is usually confined to a single joint.

Skin rashes and nail changes

Psoriatic arthritis occurs with psoriasis so skin symptoms include thick, red skin with flaky, silver-white scaly patches. Nails may become pitted or infected-looking, or even lift from the nail bed entirely. These symptoms are unique to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, actually helps doctors confirm a diagnosis.

Fatigue

People with psoriatic arthritis often experience general feelings of fatigue. This symptom is a common feature of rheumatoid arthritis.

Reduced range of motion

The inability to move joints and limbs as freely as before is a sign of psoriatic arthritis and most other forms of arthritis.

Eye problems

People with psoriatic arthritis may get inflammation of the eyes that can cause redness, irritation and disturbed vision (uveitis) or redness and pain in tissues surrounding the eyes (conjunctivitis, or “pink eye”).

Psoriatic arthritis enthesitis diagnosis

Diagnosing psoriatic arthritis can be a tricky process because its symptoms frequently mimic those of other forms of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and gout. It can also be confused with osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis.

For a proper diagnosis, the primary care doctor will likely provide a referral to a rheumatologist, a type of doctor who specializes in arthritis and musculoskeletal diseases. A diagnosis is based on many things, including a thorough medical history and the results of a physical examination and medical tests.

Medical History

Because certain conditions can be inherited, the doctor will ask questions about the health history of the patient and his or her relatives.

Additional information needed to help diagnose psoriatic arthritis includes:

- A description of the symptoms

- Details about when and how the pain or other symptoms began

- Location of the pain, stiffness or other symptoms

- How the symptoms affect the patient’s daily life

- Details about medical problems that could be causing these symptoms and a list of currently used medications

Physical exam

The rheumatologist will perform a physical exam, looking for swelling and inflammation of the joints. He’ll also check for signs of psoriasis on the skin or abnormalities on fingernails and toenails. Keep in mind that psoriasis isn’t always readily visible. It can hide on the scalp, behind the ears, in the belly button and in the groove between the buttocks.

Diagnostic tests

The doctor may order X-rays to detect changes to the bones or joints. Blood tests will be done to check for signs of inflammation. They include C-reactive protein and rheumatoid factor (RF). People with psoriatic arthritis are almost always rheumatoid factor-negative. If blood tests are positive for rheumatoid factor, the doctor should suspect rheumatoid arthritis (RA) first.

A blood test to measure the sedimentation or “sed” rate is often done. The higher the “sed rate,” the greater the level of inflammation in the body. The doctor may also test joint fluid to exclude gout or infectious arthritis.

Because psoriatic arthritis can be tricky to diagnose, people sometimes are initially told they have another form of arthritis only to find out later they have psoriatic arthritis.

Ruling out other conditions

The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis can mimic other conditions. Common misdiagnoses include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and gout. Below are some tips to help avoid a psoriatic arthritis misdiagnosis.

- If a single joint becomes swollen and extremely painful almost overnight, it’s probably gout. Gout pain comes on rapidly and is intense.

- If there is little or no joint swelling, osteoarthritis is the most likely diagnosis. Osteoarthritis pain tends to be felt after activity.

- If joint pain affects the same joint on both sides of the body (is symmetrical), it could be RA. Joint pain in psoriatic arthritis is usually asymmetrical, meaning it’s felt on one side of the body. For example, if one knee is affected, the other likely is not.

If joint pain is worse for more than a few minutes in the morning, or after inactivity, consider psoriatic arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

If swelling involves the full length of the fingers or toes, think psoriatic arthritis. This condition is called dactylitis, or “sausage fingers.”

If there are psoriasis symptoms and nail pitting first, followed by joint pain, psoriatic arthritis is likely the culprit, particularly if there is joint swelling. A person can have psoriasis and a form of arthritis that isn’t psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis enthesitis treatment

There are several over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medicines for psoriatic arthritis. Some treat symptoms of both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, others target skin problems, yet others help with joint issues. Many can also modify the disease course by disrupting the overactive immune system.

Medications for psoriatic arthritis

- NSAIDs. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually taken by mouth, although some can be applied directly to the skin. These medicines reduce inflammation along with pain and swelling. Among the most well-known over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs are ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen sodium (Aleve), although there are many others. More than a dozen prescription NSAIDs also are available. The most notable risks of NSAIDs are an increased risk of heart attack and stroke, along with stomach irritation and bleeding that could become severe.

- Corticosteroids. These drugs are designed to mimic the anti-inflammatory hormone cortisol, which is normally made by the body’s adrenal glands. Corticosteroids taken by mouth, such as prednisone, can help reduce inflammation, but long-term use can lead to side effects such as facial swelling, weight gain, osteoporosis and more. Directly injecting corticosteroids into affected joints can provide temporary inflammation relief.

- Topical treatments. Topical medicines are applied directly to the skin to treat scaly, itchy rashes due to psoriasis. Available in creams, gels, lotions, shampoos, sprays or ointments, these drugs are available OTC and by prescription. OTC ones include salicylic acid, which helps lift and peel scales, and coal tar, which may slow rapid cell growth of scales and ease itching and inflammation. Prescription topicals contain corticosteroids and/or vitamin derivatives. Common prescription ones include calcitriol, a naturally occurring form of vitamin D3; calcipotriene, a synthetic form of vitamin D3; calcipotriene combined with the corticosteroid betamethasone dipropionate; tazarotene (a vitamin-A derivative); and anthralin, a synthetic form of chrysarobin, a substance derived from the South American araroba tree.

- DMARDs. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are a varied group of medications that suppress inflammation-causing chemicals to prevent joint damage and reduce symptoms. Most are taken by mouth. According to the American College of Rheumatology, DMARDs most commonly prescribed for psoriatic arthritis are methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine and leflunomide. Azathioprine may also be prescribed. Apremilast is a newer DMARD approved in 2014. It works by blocking an enzyme called phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), which is linked to inflammation. Studies have shown it reduces the number of tender and swollen joints.

- Biologics. Technically a subset of DMARDs, biologics are complex drugs that stop inflammation at the cellular level. They are usually given by injection or infusion. Three types of biologics are approved to treat psoriatic arthritis. They include:

- Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) drugs that block a specific protein produced by immune cells that signals other cells to start the inflammatory process. These include etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab and certolizumab.

- Selective co-stimulation moderators that interfere with the activation of white blood cells called T cells, preventing immune system reactions that result in inflammation. The only drug in this class is abatacept.

- IL-inhibitors that block pro-inflammatory proteins called interleukins. The drug ustekinumab specifically blocks IL-12 and -23.

While biologics can be very effective, they suppress the immune system and raise the risk of infection.

Light therapy. Another option for treating psoriasis is phototherapy, or light therapy. In light therapy, the skin is regularly exposed to ultraviolet light. For safety reasons, this is done under medical supervision.

Achilles enthesitis

Achilles enthesitis also called achilles tendon enthesopathy, is pain at the insertion of the Achilles tendon at the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus. Diagnosis is clinical. Treatment is with stretching, splinting, and heel lifts.

The cause of Achilles enthesitis is chronic traction of the Achilles tendon on the calcaneus. Contracted or shortened calf muscles (resulting from a sedentary lifestyle and obesity) and athletic overuse are factors. Enthesitis may be caused by a spondyloarthropathy.

Pain at the posterior heel below the top of the shoe counter during ambulation is characteristic. Pain on palpation of the tendon at its insertion in a patient with these symptoms is diagnostic. Manual dorsiflexion of the ankle during palpation usually exacerbates the pain. Recurrent and especially multifocal enthesitis should prompt evaluation (history and examination) for a spondyloarthropathy.

Achilles enthesitis treatment

Physical therapy

Stretching, splinting, and heel lifts

Physical therapy is essential for home exercise programs aimed at calf muscle–stretching techniques, which should be done for about 10 min 2 to 3 times/day. The patient can exert pressure posteriorly to stretch the calf muscle while facing a wall at arms’ length, with knees extended and foot dorsiflexed by the patient’s body weight. To minimize stress to the Achilles tendon with weight bearing, the patient should move the foot and ankle actively through their range of motion for about 1 min when rising after extended periods of rest. Night splints may also be prescribed to provide passive stretch during sleep and help prevent contractures.

Heel lifts should be used temporarily to decrease tendon stress during weight bearing and relieve pain. Even if the pain is only in one heel, heel lifts should be used bilaterally to prevent gait disturbance and possible secondary (compensatory) hip and or low back pain.

For more recalcitrant forms of Achilles tendon enthesopathy, extracorporeal pulse activation therapy (EPAT) should be considered. In extracorporeal pulse activation therapy, low-frequency pulse waves are delivered locally using a handheld applicator. The pulsed pressure wave is a safe, noninvasive technique that stimulates metabolism and enhances blood circulation, which helps regenerate damaged tissue and accelerate healing.

Enthesitis symptoms

Clinical symptoms of enthesitis include tenderness, soreness, and pain at entheses on palpation.

Common spots for enthesitis to happen are around your heel, knee, hip, toe, elbow, backbone, and the bottom of your foot. The inflammation can lead to pain and stiffness, especially when you’re moving. You also might notice swelling around those areas.

Soreness at the back of your heel caused by enthesitis is sometimes called Achilles tendinitis or plantar fasciitis pain at the bottom of your foot. This pain can make it hard for you to run or climb stairs.

Over time, enthesitis can lead to:

- Calcification or ossification: Inflammation of the entheses can cause new bone tissue to form. That new bone tissue gets in the way of normal movement and function — like a bone spur on your heel.

- Fibrosis: Tissues in the affected area become ropey.

Enthesitis diagnosis

Enthesitis is hard to diagnose. The doctor will give you a physical exam, check for swelling, and to see if the area hurts when compressed. He’ll ask if the pain gets better after you exercise. You might get lab tests that look for signs of inflammation and imaging tests so your doctor can get a good view of your joints.

Enthesitis treatment

Enthesitis is treated by treating for the diseases that lead to it. Enthesitis treatment involves measures that decrease inflammation and pain. This includes rest from activity, cold application, and anti-inflammatory medications. Physical therapy is sometimes incorporated as part of the treatment regimen.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like naproxen and ibuprofen, can help with inflammation and pain. If the enthesitis is caused by an autoimmune arthritis, your doctor also may prescribe a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or biologics.

He may recommend steroids for areas that are especially stiff or painful.