What is an episiotomy

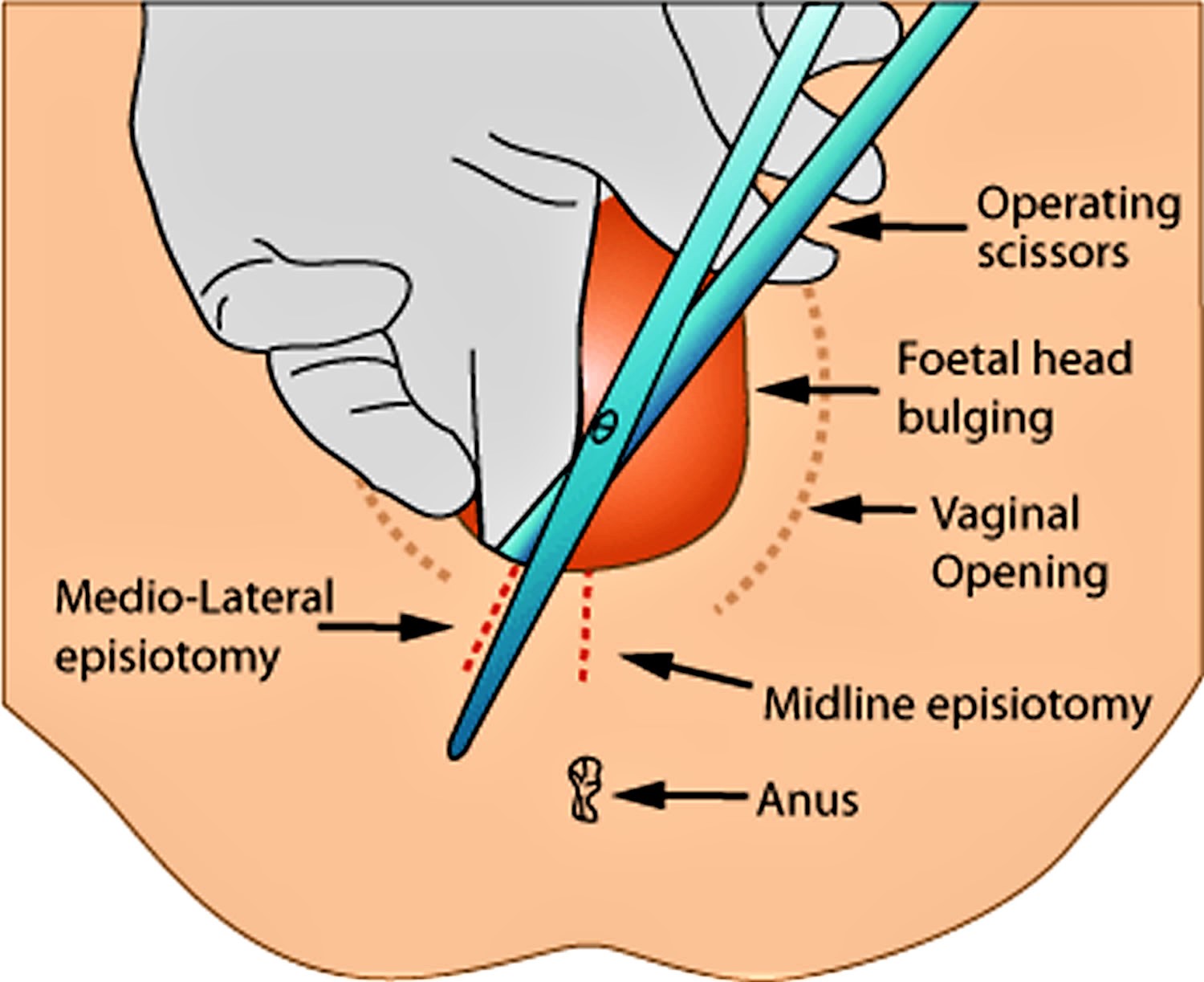

An episiotomy also known as perineotomy, is a minor surgical incision that widens the opening of the vagina and perineum during childbirth. Episiotomy is usually carried out by a skilled birth attendant to enlarge the vaginal opening 1. An episiotomy is a cut to the perineum — the skin and muscles between the vaginal opening and anus. Episiotomy is usually performed during second stage of labor to quickly enlarge the opening for the baby to pass through. An episiotomy, which can be done at a 90 degree angle from the vulva towards the anus (midline episiotomy) or at an angle from the posterior end of the vulva (medio-lateral episiotomy), is performed under local anesthetic (pudendal anesthesia), and is sutured after delivery. You shouldn’t feel any pain while your health care provider making the incision or repairing it after delivery.

Normally, once the baby’s head is seen, your healthcare provider will ease your baby’s head and chin out of your vagina. Once the baby’s head is out, the shoulders and the rest of the body follow. Sometimes the vaginal opening does not stretch enough for the baby’s head. In this case, an episiotomy aids your healthcare provider in delivering your baby. It’s important to make a surgical incision rather than letting the tissue tear. Your provider will usually do an episiotomy when the baby’s head has stretched your vaginal opening to several centimeters.

Your healthcare provider may advise an episiotomy in these situations:

- The baby does not have enough oxygen (fetal distress)

- Complicated birth, such as when the baby is positioned bottom or feet first (breech) or when the baby’s shoulders are trapped (shoulder dystocia)

- Long pushing stage of labor

- The mother needs a forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery

- Large baby

- Preterm baby

- Birth is imminent and the perineum hasn’t had time to stretch slowly

- The baby’s head is too large for the vaginal opening

- The mother isn’t able to control her pushing.

Your healthcare provider may have other reasons to recommend an episiotomy.

The first documented episiotomy dates back to over 270 years ago 2. Rates of episiotomy increased substantially during the first half of the 20th century. At that time, there was an increasing move for women to give birth in a hospital and for physicians to manage normal uncomplicated childbirths. Since then, episiotomy has become one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures in the world 3. Reported rates of episiotomies vary from as low as 9.7% (Sweden) to as high as 100% (Taiwan) 4. The large differences in episiotomy rates closely relate to the differences in policies regarding the use of episiotomy. Episiotomy rates are high in some countries, such as Argentina and China, with a policy of routine use of episiotomy for nearly all first births 5. Other places adopt a policy of ‘selective’ use of episiotomy where the use of episiotomy is restricted rather than universally performed – clinicians use their clinical judgement to determine the need for episiotomy where the benefits likely outweigh the harms in situations such as impending severe perineal tear, prolonged second stage of labor, shoulder dystocia, instrumental delivery, and non-reassuring fetal heart rate 6. In the USA, the episiotomy rate decreased from 60.9% in 1979 to 24.5% in 2004 7. In Finland, the episiotomy rate decreased from 71.5% to 54.9% between 1997 to 1999 and 2006 to 2007 among primiparous women, and from 21.5% to 9.2% between 1997 to 2001 and 2006 to 2007 among multiparous women 8.

Episiotomy is made with scissors or scalpel and requires repair by suturing 9. There are seven ways of performing an episiotomy, with ‘midline’ and ‘mediolateral’ being the two main types of episiotomy in the literature and medical practice 10. A midline (sometimes called ‘median’) episiotomy is “a vertical incision from the posterior fourchette and runs along the midline through the central tendon of the perineal body” 10. Critics point out that if a midline episiotomy extends, it is likely to extend into the anal sphincter causing a third- or fourth-degree tear. A mediolateral episiotomy is “an incision beginning in the midline and directed laterally and downwards away from the rectum” 10. In theory, if a mediolateral tear extends, it will extend away from the anal sphincter. An episiotomy is generally done late in second stage when the perineum is stretched thin. Prior to the incision, local anaesthesia is injected to numb the perineum, if a mother does not have regional anaesthesia 11.

Normal birth can cause tears to the vagina and the surrounding tissue, usually as the baby’s head is born, and sometimes these tears extend to the rectum. These are repaired surgically, but take time to heal. To avoid these severe tears, doctors have recommended making an episiotomy (surgical cut) to the perineum with scissors or scalpel to prevent severe tearing and facilitate the birth. Both a tear and an episiotomy need sutures, and can result in severe pain, bleeding, infection, pain with sex, and can contribute to long term urinary incontinence.

Many women get through childbirth without tearing their vagina on their own, and without needing an episiotomy. In fact, recent studies involving 11 randomized controlled trials (with 5977 women) that compared episiotomy as needed (selective episiotomy) with routine episiotomy in terms of benefits and harms for mother and baby in women at low risk of instrumental delivery 12 show that not having an episiotomy is best for most women in labor. Overall, the findings show that selective use of episiotomy in women (where a normal delivery without forceps is anticipated) means that fewer women have severe perineal trauma. Thus the rationale for conducting routine episiotomies to prevent severe perineal trauma is not justified by current evidence, and the research authors could not identify any benefits of routine episiotomy for the baby or the mother 12.

Episiotomy Key Findings

Routine episiotomies are no longer recommended. Routine use of episiotomy procedure does not result in maternal or fetal benefit and should be restricted, according to a practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 13. Still, episiotomy procedure is warranted in some cases (e.g., avoiding severe maternal lacerations, facilitating or expediting difficult deliveries). A systematic review comparing routine episiotomy with restrictive use reported that 72.7 percent of women in the routine-use group underwent episiotomy compared with 27.6 percent in the restricted-use group. The restricted-use group had significantly lower risks of posterior perineal trauma, suturing, and healing complications but a significant increase in anterior perineal trauma. No statistically significant differences were reported for severe vaginal or perineal trauma, dyspareunia, or urinary incontinence.

Episiotomies don’t heal better than tears. Episiotomies often take longer to heal since the surgical cut is often deeper than a natural tear. In both cases, the surgical cut or tear must be stitched and properly cared for after childbirth. At times, an episiotomy may be needed to ensure the best outcome for you and your baby.

- Labor is stressful for the baby and the pushing phase needs to be shortened to decrease problems for the baby.

- Your baby’s head or shoulders are too big for the mother’s vaginal opening.

- Your baby is in a breech position (feet or buttocks coming first) and there is a problem during delivery.

- Your baby is large (fetal macrosomia)

- Your baby needs to be delivered quickly

- Instruments (forceps or vacuum extractor) are needed to help get the baby out. Research shows that in some births, particularly with forceps deliveries, an episiotomy may prevent third-degree tears, where the tear affects the anal muscle.

- You have a serious health condition, such as heart disease, and it’s recommended that delivery should be as quick as possible to minimize any further health risks

- You have been trying to give birth for several hours and are now tired after pushing

Studies suggest that in first-time vaginal births, it’s more common to have severe injuries involving the anal muscle if the perineum tears spontaneously rather than if an episiotomy is performed.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that an episiotomy should be considered if:

- the baby is in distress and needs to be born quickly, or

- there is a clinical need, such as a delivery that needs forceps or ventouse suction cup, or a risk of a tear to the anus

Episiotomy and Maternal Postpartum Outcomes

Trials of fair to poor quality provide consistent findings that clearly support limited use of episiotomy. Routine episiotomy achieves no short‐term goals that it has been hypothesized to achieve. Indeed, routine use is harmful to the degree that it creates a surgical incision of greater extent than many women might have experienced had episiotomy not been performed.

Episiotomy Incision Type and Maternal Morbidity

A single study found that women with midline episiotomy had a significantly greater rate of anal sphincter injuries than women with mediolateral episiotomy 14. Treatment groups did not report differences in pain or satisfaction with intercourse at 3 months. Because of considerable methodological flaws in this trial (poor internal validity), any conclusions must be drawn cautiously. However, because differences in sphincter injury rates are clinically important, the study authors 15 consider the finding of increased risk of severe injury with midline episiotomy compared to mediolateral episiotomy to be relevant observational evidence.

Repair of Perineal Defect and Maternal Morbidity

Limited but consistent evidence favored two‐layer repair over three‐layer repair; limited and inconsistent evidence favored continuous over interrupted sutures. Evidence was insufficient to comment on comparisons between standard and rapidly absorbed sutures, tissue adhesive and absorbable sutures, or nonabsorbable and absorbable sutures. The study authors 15 found no evidence that treated catgut is superior to untreated catgut with regard to perineal morbidity; the former may in fact be associated with higher morbidity. The evidence suggests short‐term advantages for perineal repeat associated with the use of polyglycolic‐acid sutures compared to chromic‐catgut sutures.

Three major classes of suture material (nonabsorbable, absorbable, and tissue adhesive) and two subtypes of sutures (treated versus untreated and standard versus rapidly absorbed) were studied, all in the presence of different approaches to the method of suturing; thus, individual effects of the materials themselves cannot be examined. Likewise, methods of repair were examined in the context of different materials both among and within studies for different stages of repair. The study authors 15 are unable to assess the true effects of a certain method of repair because they cannot tell whether outcomes are confounded or modified by suture material.

Episiotomy and Urinary Incontinence, Fecal Incontinence, and Pelvic Floor Defects

These prospective studies did not identify improvements in continence for urine or stool or in pelvic floor muscle function among women who had had episiotomy compared to those who had not. This finding includes comparison to women who had spontaneous lacerations of similar severity.

Several authors reported decrements in pelvic floor function among women who had had episiotomy. Only a single study, using multivariable models, found that episiotomy was an independent predictor of urinary continence 16. In the majority of other studies using multivariate models, adjusting for factors such as parity, neonatal weight, and length of second‐stage labor, episiotomy was not an independent risk factor for incontinence. Taken in total, this literature, predominantly of fair to poor quality, does not support use of episiotomy for the purpose of preventing pelvic floor defects, urinary incontinence, or incontinence of stool or flatus.

These studies are limited because they do not follow women long enough to detect disease occurrence. At present, the assumption that intermediate variables, such as pelvic muscle strength measured by perineometry, urodynamic test results, or early reports of symptoms, can predict later disease has not been validated. Prospective evaluation only during the months after birth when the pelvic floor is still in a recovery and stabilization period may be misleading. Conclusions about whether episiotomy prevents or increases risk for incontinence and prolapse later in adult life cannot be reached from currently available randomized and cohort studies.

The data available show that at one-year follow-up, immediate primary overlap repair of the external anal sphincter compared with immediate primary end-to-end repair appears to be associated with lower risks of developing fecal urgency and anal incontinence symptoms 17. At the end of 36 months there appears to be no difference in flatus or fecal incontinence between the two techniques. However, since this evidence is based on only two small trials, more research evidence is needed in order to confirm or refute these findings.

Episiotomy and Future Sexual Function

The studies addressing this question need to be considered in two groups: mediolateral episiotomy and midline episiotomy. From the clinical trials of episiotomy strategy—liberal versus restrictive—one trial addressed each type of incision and one directly compared the two incision types. None found substantive differences in sexual function. The preponderance of the studies, however, supported a conclusion that degree of perineal trauma is associated with probability of pain with intercourse, in a dose‐response fashion such that greater perineal injury is associated with greater probability of pain.

Measures that are more complex than those typically used in the literature are needed to understand properly the relationships between perineal trauma and future sexual function. Specific factors such as prior sexual function and current libido, in addition to factors such as duration of second‐stage labor, size of infant, and lactation status, need to be incorporated into multivariable models to derive more informative and less biased estimates of the long‐term effects of episiotomy or to determine that they do not exist.

Figure 1. Episiotomy

Figure 2. Female reproductive system

Female pelvic floor

The pelvic floor is a complex layer of muscles and ligaments which stretches like a hammock from the pubic bone at the front of your pelvis to the coccyx at the bottom your spine (see Figure 3).

The muscles of the pelvic floor are the levator ani and ischiococcygeus. Along with the fascia covering their internal and external surfaces, these muscles are referred to as the pelvic diaphragm, which stretches from the pubis anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly, and from one lateral wall of the pelvis to the other. This arrangement gives the pelvic diaphragm the appearance of a funnel suspended from its attachments. The pelvic diaphragm separates the pelvic cavity above from the perineum below. The anal canal and urethra pierce the pelvic diaphragm in both sexes, and the vagina also goes through it in females. The three components of the levator ani muscle are the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus. The levator ani is the largest and most important muscle of the pelvic floor. It supports the pelvic viscera and resists the inferior thrust that accompanies increases in intraabdominal pressure during functions such as forced exhalation, coughing, vomiting, urination, and defecation. The muscle also functions as a sphincter at the anorectal junction, urethra, and vagina. In addition to assisting the levator ani, the ischiococcygeus pulls the coccyx anteriorly after it has been pushed posteriorly during defecation or childbirth.

Figure 3. Pelvic floor female

Episiotomy vs Tear

Vaginal birth can cause tears to the vagina and perineum. Estimates of the frequency vary, with some estimates (that include episiotomy) indicating this occurs in 85% of births 18, compared with a more recent retrospective cohort reporting that 4% of 1785 Australian women sustained a perineal scrape and 34% sustained a first- or second-degree perineal tear 19. While minor tears may heal quickly without intervention, some are more severe, damaging tissue, muscle and sometimes extending to the anal sphincter. These more severe tears need surgical repair, and depending on the extent, may cause a number of problems in the early postnatal period. Women may experience pain, bleeding, infection, dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), and have a prolonged hospital stay. In a small percentage of women, the damage to the vaginal and perineal tissues can result in some long-term problems such as pain, urinary fistula (an abnormal connection between vagina and bladder), urinary incontinence (the inability of control causing urinary ‘accidents’), rectal fistula (an abnormal connection between the vagina and rectum), fecal incontinence (the inability of control causing fecal ‘accidents’), dyspareunia and genital-urinary prolapse (the pelvic organs descending from their normal position) 18.

Tears of the perineum and vagina are classified as follows 17:

- First degree: involving the fourchette, perineal skin and vaginal mucous membrane, but not the underlying fascia and muscle;

- Second degree: involving the perineal muscles and skin but not involving the anal sphincter;

- Third degree: injury to the anal sphincter complex;

- 3a: less than 50% of the external anal sphincter torn;

- 3b: 50% of the external anal sphincter torn; and

- 3c: the external and internal anal sphincter are torn;

- Fourth degree: injury extends through the anal sphincter complex (external anal sphincter and internal anal sphincter) to ano-rectal epithelium epithelium.

Severe perineal trauma usually refers to a third-degree or fourth-degree tear 20.

Preventing a perineal tear

A midwife can help you avoid a tear during labor when the baby’s head becomes visible.

The midwife will ask you to stop pushing and to pant or puff a couple of quick short breaths, blowing out through your mouth.

This is so your baby’s head can emerge slowly and gently, giving the skin and muscles of the perineum time to stretch without tearing.

The skin of the perineum usually stretches well, but it may tear, especially in women who are giving birth for the first time.

Research suggests massaging the perineum in the last few weeks of pregnancy can reduce the chances of having an episiotomy during birth.

A review of four trials showed massaging the perineum from 35 weeks of pregnancy reduced the likelihood of tears, needing an episiotomy, and pain in women who had not given birth vaginally before.

The type and frequency of massage varied across the trials. Most involved inserting one or two fingers into the vagina and applying downward or sweeping pressure towards the perineum.

The benefit was more marked among those women who carried out perineal sweeping twice a week.

The role of warm compresses and tissue massage

During the second stage of labor — when you’re pushing — your health care provider might apply warm compresses or warm mineral oil to the tissue between your vaginal opening and your anus. This might soften the tissue and help prevent tears in the skin.

Although the evidence for warm compresses is stronger, some health care providers also massage the area between the vaginal opening and the anus as labor progresses. This is known as perineal massage.

Your health care provider might even recommend trying perineal massage at home after week 34 of pregnancy. To get started, wash your hands and rub a mild lubricant, such as K-Y jelly, on your thumbs. Place your thumbs just inside your vagina and press downward toward your rectum. Hold for one to two minutes. Then, slowly massage the lower half of your vagina. Repeat the massage once a day for 10 minutes at a time until delivery.

How episiotomy might work

Episiotomy, a surgical cut of the vagina and perineum, is sometimes used in an attempt to prevent serious perineal damage caused by tearing and to facilitate the birth of the baby.

It is thought that enlarging the vaginal outlet by episiotomy would reduce vaginal soft tissue stretching and tension during childbirth, thereby preventing higher degrees of perineal traumas and their subsequent complications 21. More space also allows for instrumentation of assisted deliveries by forceps or vacuums 22. At other times, episiotomy is performed to shorten second stage of labor for various maternal and fetal indications 23 such as maternal exhaustion and fetal bradycardia.

Clinicians who advocate routine episiotomies reason that perineal tears, including severe tears, can occur in women who are not thought likely to have serious tears and who have not had an episiotomy under a selective regimen. However, the effectiveness of routine episiotomy preventing severe perineal trauma has been questioned and the procedure has its own associated complications. Since not all vaginal births result in perineal trauma, some women are subjected to unnecessary incisions and their associated complications and morbidity as a result of a ‘routine’ episiotomy policy. Even in obstetrical emergencies such as shoulder dystocia, and in instrumental-assisted deliveries, episiotomy may not reduce severe perineal tears 24.

Complications associated with episiotomy include bleeding, pain and discomfort of the wound and sutures (which may cause pain while sitting, and in turn affect breastfeeding), wound scarring, dyspareunia, or complications in subsequent vaginal births. Other adverse effects of episiotomy include: (a) extension of episiotomy through the anal sphincter and rectum by the clinician making the incision, or by spontaneous extension of the incision; (b) unsatisfactory anatomic healing resulting in skin tags, asymmetry or excessive narrowing of the introitus, vaginal prolapse, recto-vaginal fistula and fistula-in-ano 25; (c) increased blood loss and hematoma; (d) pain and oedema around the episiotomy wound; (e) infection and dehiscence 25; (f) dyspareunia, which may be a short-term consequence, or may become more established and cause persistent dyspareunia 26; and finally, (h) at least one woman has died as a result of infection complicating an episiotomy wound 27.

How can I avoid an episiotomy?

You can do things to strengthen your body for labor that may lower your chances of needing an episiotomy.

- Practice Kegel exercises.

- Perform perineal massage during the 4 to 6 weeks before birth. To get started, wash your hands and rub a mild lubricant, such as K-Y jelly, on your thumbs. Place your thumbs just inside your vagina and press downward toward your rectum. Hold for one to two minutes. Then, slowly massage the lower half of your vagina. Repeat the massage once a day for 10 minutes at a time until delivery.

- Practice the techniques you learned in childbirth class to control your breathing and your urge to push.

- A slowed second stage of labor where pushing is controlled

- Warm compresses and support during delivery

- Use of perineum massage techniques

- Avoiding lying on your back while pushing

- Good nutrition–healthy skin stretches more easily.

Keep in mind, even if you do these things, you may still need an episiotomy. Your obstetrician will decide if you should have one based on what happens during your labor.

How to do Kegel Exercises

Pelvic floor, or Kegel, exercises involve strengthening pelvic floor muscles. Strong pelvic floor muscles more effectively hold pelvic organs in place. A woman does not need special equipment for Kegel exercises.

The exercises involve tightening and relaxing the muscles that support pelvic organs. A health care provider can help a woman learn proper technique.

A Kegel exercise is like pretending you have to urinate and then holding it. You relax and tighten the muscles that control urine flow. It is important to find the right muscles to tighten.

Next time you have to urinate, start to go and then stop. Feel the muscles in your vagina (for women), bladder, or anus get tight and move up. These are the pelvic floor muscles. If you feel them tighten, you have done the exercise right. Your thighs, buttock muscles, and abdomen should remain relaxed.

If you still are not sure you are tightening the right muscles:

- Imagine that you are trying to keep yourself from passing gas.

- Women: Insert a finger into your vagina. Tighten the muscles as if you are holding in your urine, then let go. You should feel the muscles tighten and move up and down.

Let your doctor, nurse, or therapist help you. Many people have trouble finding the right muscles. Your doctor, nurse, or therapist can check to make sure you are doing the exercises correctly. You can also exercise by using special weights or biofeedback. Ask your health care team about these exercise aids.

Don’t squeeze other muscles at the same time. Be careful not to tighten your stomach, legs, or other muscles. Squeezing the wrong muscles can put more pressure on your bladder control muscles. Just squeeze the pelvic muscle. Don’t hold your breath.

Step 1

Sit comfortably with your knees slightly apart. Imagine that you are trying to stop yourself passing wind from your bowel. To do this, you must squeeze the muscle around the back passage. Try lifting and squeezing the muscle as if you have wind. If you sense a “pulling” feeling, you are squeezing the right muscles for pelvic exercises. You should be able to feel the muscle move and your buttocks or legs should not move at all. You should notice that the skin around your back passage tightens up and creates the sensation of lifting you from your chair.

Step 2

Imagine that you are sitting on the toilet to pass urine and try to stop yourself from producing a stream of urine. You should be using the same group of muscles that you used before but you will find this a little more difficult. Do not try to stop the urinary stream when you are actually passing water because it can cause problems with bladder emptying.

Or you can lie down and put your finger inside your vagina. Squeeze as if you were trying to stop urine from coming out. If you feel tightness on your finger, you are squeezing the right pelvic muscles.

Step 3

Try to tighten the muscles around your back passage and vagina, by lifting up inside as if you are trying to stop passing wind and urine at the same time. Do not tense your abdomen, squeeze your legs together, tighten your buttocks or hold your breath. If you can master this, most of the muscle contraction should be coming from the pelvic floor.

How do you practice the exercises?

You need to develop two types of muscle activity, slow and fast.

- to practice slow contractions

- do the exercises above and try to hold the pelvic floor tight for up to ten seconds. Rest for four seconds and then repeat the contraction as many times as you can, up to a maximum of ten

- to practice quick contractions

- draw the pelvic floor rapidly upwards and hold this for one second. Repeat up to a maximum of ten times. This will protect you against sudden leakage during coughing, laughing or exercise

- Aim to do one set of slow contractions followed by one set of fast contractions up to six times a day. Do not over-do it or the muscles will get tired. The exercises can be performed standing, sitting or lying down but you may find it easier at first to do them sitting down.

Once you know what the movement feels like, do Kegel exercises 3 times a day:

- Make sure your bladder is empty, then sit or lie down.

- Tighten your pelvic floor muscles. Hold tight and count to 8.

- Relax the muscles and count to 10.

- Repeat 10 times, 3 times a day (morning, afternoon, and night).

Breathe deeply and relax your body when you are doing these exercises. Make sure you are not tightening your stomach, thigh, buttock, or chest muscles.

After 4 to 6 weeks, you should feel better and have fewer symptoms. Keep doing the exercises, but do not increase how many you do. Overdoing it can lead to straining when you urinate or move your bowels.

Some notes of caution:

- Once you learn how to do them, do not practice Kegel exercises at the same time you are urinating more than twice a month. Doing the exercises while you are urinating can weaken your pelvic floor muscles over time or cause damage to bladder and kidneys.

- In women, doing Kegel exercises incorrectly or with too much force may cause vaginal muscles to tighten too much. This can cause pain during sexual intercourse.

- Incontinence will return if you stop doing these exercises. Once you start doing them, you may need to do them for the rest of your life.

- It may take several months for your incontinence to lessen once you start doing these exercises.

Other things that help

- Get into the habit of doing your exercises regularly and linking them to everyday activities e.g. do them after emptying your bladder, while answering the telephone, standing in a queue or whenever you turn on a tap. Do your pelvic exercises at least three times a day. Every day, use three positions: lying down, sitting, and standing. You can exercise while lying on the floor, sitting at a desk, or standing in the kitchen. Using all three positions makes the muscles strongest.

- At first, find a quiet spot to practice—your bathroom or bedroom—so you can concentrate. Lie on the floor. Pull in the pelvic muscles and hold for a count of 3. Then relax for a count of 3. Work up to 10 to 15 repeats each time you exercise.

- If you are not sure you are doing the exercises correctly, insert a thumb or two fingers into the vagina and try the exercises; you should feel a gentle squeeze as the muscles contract

- Use the pelvic floor exercises to prevent leakage before you do anything which might make you leak; this way, your control will gradually improve

- Drink normally – six to eight cups (two liters) per day – avoiding caffeine and alcohol if you can

- Avoid going to the toilet “just in case”; go only when you feel that your bladder is full

- Watch your weight; extra weight puts more strain on your pelvic floor muscles and your bladder

- Avoid constipation. Straining can put excessive pressure on your bladder and bowels

- Pelvic floor exercises take three to six months to produce maximum benefit, but you should continue them for life to prevent problems recurring or worsening; you should seek help from a health professional there is little or no change in your symptoms after exercising for three months

- Other methods which help some women include weighted vaginal cones, biofeedback and electrical stimulation; consult your doctor, urologist or specialist nurse for more details

Be patient. Don’t give up. It’s just 5 minutes, three times a day. You may not feel your bladder control improve until after 3 to 6 weeks. Still, most women do notice an improvement after a few weeks.

Use the Exercise Log below to keep track of your sessions.

Week: ______________

My Pelvic Muscle Exercise Log

Sunday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Monday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Tuesday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Wednesday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Thursday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Friday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Saturday

- I exercised my pelvic muscles ____ times.

- I spent ____ minutes exercising.

- At each exercise session, I squeezed my pelvic muscles ____ times.

Figure 4. Pelvic floor muscle exercise log – use this sheet as a master for making copies that you can use to record your exercises week after week.

Episiotomy risks

There are some risks to having an episiotomy. Because of the risks, episiotomies are not as common as they used to be. The risks include:

Complications associated with episiotomy include:

- Bleeding,

- Pain and discomfort of the wound and sutures (which may cause pain while sitting, and in turn affect breastfeeding),

- Wound scarring,

- Dyspareunia (painful sex). Sex may be painful for the first few months after birth.

- Complications in subsequent vaginal births.

- The cut may tear and become larger during the delivery. The tear may reach into the muscle around the rectum, or even into the rectum itself.

- There may be more blood loss.

- The cut and the stitches may get infected.

Other adverse effects of episiotomy include:

- (a) extension of episiotomy through the anal sphincter and rectum by the clinician making the incision, or by spontaneous extension of the incision;

- (b) unsatisfactory anatomic healing resulting in skin tags, asymmetry or excessive narrowing of the introitus, vaginal prolapse, recto-vaginal fistula and fistula-in-ano 25;

- (c) increased blood loss and hematoma;

- (d) pain and oedema around the episiotomy wound;

- (e) infection and dehiscence 25;

- (f) dyspareunia, which may be a short-term consequence, or may become more established and cause persistent dyspareunia 26; and finally,

- (h) at least one woman has died as a result of infection complicating an episiotomy wound 27.

What happens if you need an episiotomy?

Just before your baby is born and as the head is about to crown, your doctor or midwife will give you local anaesthetic to numb the area so you won’t feel any pain (if you have not already had an epidural). If you’ve already had an epidural, the dose can be topped up before the cut is made.

Next, a small incision (cut) is made. There are 2 types of cuts: midline (median) and medio-lateral.

- A midline episiotomy is the most common type. It is a straight cut in the middle of the area between the vagina and anus (perineum). A midline incision is the easiest to repair, but has a higher risk of extending into the anal area. Median episiotomy is associated with a greater risk of extension to the anal sphincter (third-degree extension) or rectum (fourth-degree extension).

- A mediolateral episiotomy is made at an angle. It is less likely to tear through to the anus, but it takes longer to heal than the median cut and might be more difficult to repair. Reported disadvantages of the mediolateral procedure include greater blood loss, and, possibly, more discomfort during the early postpartum period. Although the data are insufficient to determine the superiority of either approach, the procedures seem to have similar outcomes, including pain from the incision and time to resumption of intercourse.

Generally, an episiotomy follows this process:

- You will lie on a labor bed, with your feet and legs supported for the birth.

- If you have not been given any anesthesia, your provider will inject a local anesthetic into the perineal skin and muscle. This will numb the tissues before the incision is made. If epidural anesthesia is used, you will have no feeling from your waist down. In this case, you won’t need more anesthesia for the episiotomy.

- During the second stage of labor (pushing stage), as your baby’s head stretches your vaginal opening, your healthcare provider will use surgical scissors or a scalpel to make the episiotomy incision.

- Your health care provider will then deliver the baby through the enlarged opening.

- Next, your provider will deliver the placenta (afterbirth).

- He or she will check the incision for any further tearing.

- Your provider will use stitches (sutures) to repair the perineal tissues and muscle. The stitches will dissolve over time.

You shouldn’t feel any pain while your health care provider making the incision or repairing it after delivery.

Episiotomy healing

After an episiotomy, you may have pain at the incision site. An ice pack may help reduce swelling and pain. Warm or cold shallow baths (sitz baths) may ease soreness and speed healing. Medicated creams or local numbing sprays may also be helpful.

You may take a pain reliever as recommended by your doctor. Be sure to take only recommended medicines.

Keep the incision clean and dry using the method your healthcare provider recommends. This is important after urination and bowel movements. If bowel movements are painful, stool softeners recommended by your healthcare provider may be helpful.

Do not douche, use tampons, or have sex until your healthcare provider says it’s OK. You may also have other limits on your activity, including no strenuous activity or heavy lifting.

You may go back to your normal diet unless your healthcare provider tells you otherwise.

Your healthcare provider will tell you when to return for further treatment or care.

Your healthcare provider may give you other instructions after the procedure, based on your situation.

Wait 6 weeks before you:

- Use tampons

- Have sex

- Do any other activity that might rupture (break) the stitches

Coping with pain

It’s common to feel some pain after an episiotomy. Painkillers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) can help relieve pain and are safe to use if you’re breastfeeding.

You shouldn’t take ibuprofen if you’re breastfeeding and your baby was born premature (before 37 weeks of pregnancy), had a low birth weight, or has a medical condition.

Aspirin also isn’t recommended as it can be passed on to your baby through your breast milk. Your midwife will advise you if you’re not sure what painkillers to take.

Research suggests around 1% of women (1 in 100) feel severe pain that seriously affects their day-to-day activities and quality of life after having an episiotomy.

If this happens, it may be necessary to treat the pain with stronger prescription-only painkillers, such as codeine.

However, prescription-only medicine may affect your ability to breastfeed safely. Your doctor or midwife will be able to advise you about this.

To ease the pain, you can try:

- placing an ice pack or ice cubes wrapped in a towel on the incision – avoid placing ice directly on to your skin as this could cause damage

- using a doughnut-shaped cushion or squeezing your buttocks together while you’re sitting to help relieve pressure and pain at the site of your cut

Exposing the stitches to fresh air can help encourage the healing process. Taking off your underwear and lying on a towel on your bed for around 10 minutes once or twice a day may help.

It’s unusual for postoperative pain to last longer than two to three weeks. If the pain lasts longer than this, you should speak to a doctor, health visitor, or another health professional.

How long does it take for an episiotomy to heal?

Stitches should heal within one month of the birth. Most women heal without problems, although it may take many weeks. If you have an episiotomy or tear during delivery, the wound might hurt for a few weeks — especially when you walk or sit. If the incision or tear is extensive, the tenderness might last longer. Any stitches used to repair the episiotomy will usually be absorbed on their own.

You can return to normal activities when you feel ready, such as light office work or house cleaning.

To promote healing:

- Soothe the wound. Cool the wound with an ice pack, or place a chilled witch hazel pad between a sanitary napkin and the wound.

- Take the sting out of urination. Pour warm water over your vulva during urination, and rinse yourself with a squeeze bottle afterward.

- Take warm baths, but wait until 24 hours after you have given birth. Make sure that the bathtub is cleaned with a disinfectant before every bath.

- Prevent pain and stretching during bowel movements. Press a clean pad against the wound when passing a bowel movement.

- Sit down carefully. Tighten your buttocks as you lower yourself to a seated position. Sit on a pillow or padded ring.

- Use medication as needed. Your health care provider might order prescription medications or recommend an over-the-counter pain reliever or stool softener. However, pain-relieving creams or ointments haven’t been found to be effective for episiotomy wounds.

- Consider complementary treatments. Some research suggests that lavender might help relieve pain after a tear or episiotomy. If your health care provider approves, add a few drops of lavender essential oil to your bath water or apply the oil directly to the tissue between your vaginal opening and your anus.

You can do many other things to help speed up the healing process, such as:

- Use sitz baths (sit in water that covers your vulvar area) a few times a day. Wait until 24 hours after you have given birth to take a sitz bath as well. You can buy tubs in any drug store that will fit on the rim of the toilet. If you prefer, you can sit in this kind of tub instead of climbing into the bathtub.

- Change your pads every 2 to 4 hours.

- Keep the area around the stitches clean and dry. Pat the area dry with a clean towel after you bathe.

- After you urinate or have a bowel movement, spray warm water over the area and pat dry with a clean towel or baby wipe. DO NOT use toilet paper.

- Do Kegel exercises. Squeeze the muscles that you use to hold in urine for 5 minutes. Do this 10 times a day throughout the day.

- Take stool softeners and drink lots of water. This will prevent constipation. Eating lots of fiber will also help. Your health care provider can suggest foods with plenty of fiber.

While you’re healing, expect the discomfort to progressively improve. Contact your health care provider if the pain intensifies, you develop a fever or the wound produces a pus-like discharge. These could be signs of an infection.

Going to the toilet

Keep the cut and the surrounding area clean to prevent infection. After going to the toilet, pour warm water over your vaginal area to rinse it.

Pouring warm water over the outer area of your vagina as you pee may also help ease the discomfort.

You may find squatting over the toilet, rather than sitting on it, reduces the stinging sensation when passing urine.

When you’re passing a stool, you may find it useful to place a clean pad at the site of the cut and press gently as you poo. This can help relieve pressure on the cut.

When wiping your bottom, make sure you wipe gently from front to back. This will help prevent bacteria in your anus infecting the cut and surrounding tissue.

If you find passing stools particularly painful, taking laxatives may help. This type of medication is usually used to treat constipation and makes stools softer and easier to pass.

Most laxatives work within 3 days. They should only be used for a short time.

The most common causes of constipation include:

- not eating enough fiber – such as fruit, vegetables and cereals

- not drinking enough fluids

- not exercising or being less active

- often ignoring the urge to go to the toilet

- changing your diet or daily routine

- stress, anxiety or depression

- a side effect of medication

Constipation is also common during pregnancy and for 6 weeks after giving birth.

In much rarer cases, constipation may be caused by a medical condition.

How you can treat constipation yourself

Simple changes to your diet and lifestyle can help treat constipation. It’s safe to try these simple measures when you’re pregnant.

You may notice a difference within a few days. Sometimes it takes a few weeks before your symptoms improve.

Make changes to your diet

To make your stool softer and easier to pass:

- drink plenty of fluids and avoid alcohol

- increase the fiber in your diet

- add some wheat bran, oats or linseed to your diet

Increase your activity

A daily walk or run can help you to defecate more regularly.

Improve your toilet routine

Keep to a regular time and place and give yourself plenty of time to use the toilet. Don’t delay if you feel the urge to poo.

To make it easier to poo, try resting your feet on a low stool while going to the toilet. If possible, raise your knees above your hips.

Pain during sex

There are no rules about when to start having sex again after you’ve given birth.

In the weeks after giving birth, many women feel sore as well as tired, whether they’ve had an episiotomy or not. Don’t rush into it. If sex hurts, it won’t be pleasurable.

If you’ve had a tear or an episiotomy, pain during sex is very common in the first few months.

Studies have found around 9 out of 10 women who had an episiotomy reported resuming sex after the procedure was very painful, but pain improves over time.

If penetration is painful, say so. If you pretend everything is all right when it isn’t, you may start to see sex as a nuisance rather than a pleasure, which won’t help you or your partner.

You can still be close without having penetration – for example, through mutual masturbation.

Pain can sometimes be linked to vaginal dryness. You can try using a water-based lubricant available from pharmacies to help.

Don’t use an oil-based lubricant, such as Vaseline or moisturising lotion, as this can irritate the vagina and damage latex condoms or diaphragms.

You can get pregnant as little as three weeks after the birth of a baby, even if you’re breastfeeding and your periods haven’t started again.

Use some kind of contraception every time you have sex after giving birth, including the first time (unless you want to get pregnant again).

You’ll usually have an opportunity to discuss your contraceptive options before you leave hospital (if you’ve had your baby in hospital) and at the postnatal check.

You can also talk to your doctor, midwife or health visitor, or go to a contraception clinic at any time.

Pelvic Floor Exercises

Strengthening the muscles around the vagina and anus by doing pelvic floor exercises can help promote healing, and will reduce the pressure on the cut and surrounding tissue.

Pelvic floor exercises involve squeezing the muscles around your vagina and anus as though to stop yourself from going to the loo or passing wind (farting).

Episiotomy infection

Tell your healthcare provider if you have any of the following:

- Bleeding from the episiotomy site

- Your pain gets worse.

- You go for 4 or more days without a bowel movement.

- You pass a blood clot larger than a walnut.

- Foul-smelling vaginal drainage

- Fever or chills

- Severe perineal pain

Episiotomy scar tissue

For a few women, excessive, raised or itchy scar tissue forms around the place where a tear happened or where an episiotomy was performed. If your scar tissue is causing problems for you, tell your doctor.

Scar tissue doesn’t stretch, so you may need an episiotomy again if you have excessive scar tissue and you have another baby. You can talk to your midwife or doctor about this.

References- FIGO Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health (SMNH) Committee. Management of the second stage of labor. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2012;119:110-6.

- Ould F. A Treatise of Midwifery. London: J Buckland, 1741.

- Graham ID. Episiotomy-Challenging Obstetric Interventions. Blackwell Science, 1997.

- Graham ID, Carroli G, Davies C, Medves JM. Episiotomy rates around the world: an update. Birth 2005;7(313):21.

- Qian X, Smith H, Zhou L, Liang J, Garner P. Evidence-based obstetrics in four hospitals in China: an observational study to explore clinical practice, women’s preferences and provider’s views. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2001;1:1.

- Melo I, Katz L, Coutinho I, Amorim MM. Selective episiotomy vs. implementation of a non episiotomy protocol: a randomized clinical trial. Reproductive Health 2014;11(1):66.

- Frankman EA, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Episiotomy in the United States: has anything changed?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;200(5):e1-e7.

- Räisänen S, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Gisler M, Heinonen S. A population-based register study to determine indications for episiotomy in Finland. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2011;115:26-30.

- Thacker SB, Banta HD. Benefits and risks of episiotomy: an interpretative review of the English language literature, 1860-1980. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 1983;38:322-38.

- Kalis V, Laine K, De Leeuw JW, Ismail KM, Tincello DG. Classification of episiotomy: towards a standardisation of terminology. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics & gynaecology 2012;119(5):522-6.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin. Episiotomy. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 71, April 2006. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2006;107(4):957-62.

- Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, Garner P. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000081. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub3. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub3/full

- ACOG Recommends That Physicians Restrict Episiotomy. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Dec 1;74(11):1970-1976. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/1201/p1970a.html

- Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M. et al. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87(5):408–12.

- Viswanathan M, Hartmann K, Palmieri R, et al. The Use of Episiotomy in Obstetrical Care: A Systematic Review: Summary. 2005 May. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 1998-2005. 112. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11967

- Viktrup L, Lose G. The risk of stress incontinence 5 years after first delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(1):82–7.

- Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Kettle C, Thakar R. Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD002866. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002866.pub3. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002866.pub3/full

- Kettle C, Tohill S. Perineal care. Clinical Evidence 2008;9:1401.

- Catling-Paull C, Coddington RL, Foureur MJ, Homer CSE, on behalf of the Birthplace in Australia Study and the National Publicly-funded Homebirth Consortium. Publicly funded homebirth in Australia: a review of maternal and neonatal outcomes over 6 years. Medical Journal of Australia 2013;198(11):616-20. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2013/198/11/publicly-funded-homebirth-australia-review-maternal-and-neonatal-outcomes-over

- Priddis H, Dahlen H, Schmied V, Sneddon A, Kettle A, Brown C, et al. Risk of recurrence, subsequent mode of birth and morbidity for women who experienced severe perineal trauma in a first birth in New South Wales between 2000 – 2008: a population based data linkage study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2013;13:89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3635942/

- Cunningham FG. Conduct of normal labor and delivery. In: Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap LC III editor(s). Williams Obstetrics. 19. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange, 1993:371-93.

- Murphy DJ, Macleod M, Bahl R, Goyder K, Howarth L, Strachan B. A randomised controlled trial of routine versus restrictive use of episiotomy at operative vaginal delivery: a multicentre pilot study. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2008;115(13):1695-703.

- Hartmann K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, Gartlehner G, Thorp J, Lohr KN. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293(17):2141-8.

- Steiner N, Weintraub AY, Wiznitzer A, Sergienko R, Sheiner E. Episiotomy: the final cut?. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2012;286(6):1369-73.

- Homsi R, Daikoku NH, Littlejohn J, Wheeless CR Jr. Episiotomy: risks of dehiscence and rectovaginal fistula. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 1994;49:803-8.

- Garner P. Dyspareunia after episiotomy. British Journal of Sexual Medicine 1982;1:1-3.

- Lynch CM, Pinelli DM, Cruse CW, Spellacy WN, Sinnott JT, Shashy RG. Maternal death from postpartum necrotizing fasciitis arising in an episiotomy: a case report. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;5(5):341-4.