Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

FASD or fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is the term used to describe the physical and/or neurodevelopmental impairments that can occur in a person whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy. People with FASD can experience lifelong problems, such as learning difficulties, mental illness, and drug and alcohol problems.

There is a total of five disorders that comprise FASD. They are fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), a neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE), and alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD) 1. All of these fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are used to classify the wide-ranging physical and neurological effects that prenatal alcohol exposure can inflict on a fetus 2.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a condition that may be diagnosed in a person who, before they were born, was exposed to alcohol. The alcohol in any alcoholic drink (beer, wine or spirits) is rapidly absorbed into the mother’s blood stream and crosses the placenta to the unborn child to change otherwise healthy development. FASD is characterized by damage to the developing brain, leading to abnormalities in how the brain works. This can show up in several different ways, such as problems with learning, memory, language, judgement, decision-making and planning, movement or sensation. Some, but not all individuals can also have facial features that are characteristic of FASD. Alcohol can cause harm to the unborn child at any time during pregnancy (including before pregnancy is confirmed) and the level of harm depends on the pattern of the mother’s alcohol use – the percentage of alcohol in drinks, the number of drinks, and over what time the alcohol drinks were consumed. Binge drinking for example, means a high level of alcohol is consumed in a shorter period of time. In addition to the alcohol exposure, the vulnerability of a pregnancy and an unborn child may also be affected by other factors like genetics, family alcohol use across generations, the father’s alcohol use prior to conception, the mother’s age and general health (for example, nutrition, tobacco use) and other environmental factors like stress (exposure to violence, living with poverty, factors at work). FASD is not always obvious at birth and might not be noticed until the child doesn’t reach developmental milestones or behavior and learning difficulties become a worry once the child starts school. FASD can also be first diagnosed in adolescence or adulthood. Different professionals might need to be involved to assess the areas of the child’s life where help is most needed. A person who was exposed to alcohol before they were born might now be any age. A proper diagnosis, appropriate services and support can help any person living with FASD to prevent behavior from worsening, encourage attendance and participation at school, and help sustain work and build understanding, social relationships and friendships. Parents, families and communities need to be involved in this individual’s life and work together. FASD lasts a lifetime but with the right help and caring, a good quality of life is possible. Care at home is incredibly important but can be challenging.

Prenatal alcohol exposure is the leading cause of preventable congenital disabilities. Because the presentation of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders can vary so widely, and because of recent changes to the diagnostic criteria that define these conditions, the exact prevalence is difficult to determine. Across the United States, in the 1980s and 1990s, fetal alcohol syndrome was estimated to occur in the range of 0.5 to 2 cases per 1000 live births. However, it is widely accepted that these studies underreported the problem as the other conditions that comprise fetal alcohol spectrum disorders were not defined at the time and thus not recognized. Using the more recent definitions of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders that take into account the wide range of effects that prenatal alcohol exposure can elicit, recent studies in the United States have shown that currently, fetal alcohol syndrome ranges from six to nine cases per 1000. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders range from 24 to 48 cases per 1000. The higher ends of these ranges are seen in high-risk populations such as those with low socioeconomic status and those of racial and ethnic minority populations. American Indians have some of the highest rates overall. The prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome has been reported to be as high as 1.5% among children in the foster care system 3.

In many cases, prenatal alcohol exposure is unintentional because women continue their normal drinking patterns before they know they are pregnant. Most women stop drinking alcohol once made aware of their pregnancy. Despite this fact, 7.6% of women report continued drinking during pregnancy.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder causes

All of the conditions that comprise fetal alcohol spectrum disorders stem from one common cause, which is prenatal exposure to alcohol. Alcohol is extremely teratogenic to a fetus. Its effects are wide-ranging and irreversible. Although higher amounts of prenatal alcohol exposure have been linked to increased incidence and severity of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, there are no studies that demonstrate a safe amount of alcohol that can be consumed during pregnancy. There is also no safe time during pregnancy in which alcohol can be consumed without risk to the fetus. Alcohol is teratogenic during all three trimesters. In summary, any amount of alcohol consumed at any point during pregnancy has the potential cause of irreversible damage that can lead to a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder 4.

When you drink, alcohol passes from your blood through your placenta and to the unborn child, which can seriously affect your baby’s development, particularly your baby’s brain.

The first trimester is the time when your baby’s organs are developing most quickly. Your baby’s brain continues to develop throughout pregnancy and drinking alcohol at any time can damage different parts of your baby’s brain. There is no level of drinking alcohol that can be guaranteed to be completely ‘safe’ or ‘no risk’. There is no ‘safe time’ to drink alcohol during pregnancy.

How much you drink matters. The more you drink, the more likely it is that the baby will suffer some harm. The more alcohol and the more frequently alcohol is consumed during pregnancy, the higher the risk of FASD.

If you’re planning a pregnancy or know you are pregnant, avoiding alcohol altogether is the best way to prevent FASD.

The exact mechanism by which alcohol causes its teratogenic effects is not known. For obvious ethical reasons, formal studies on the effects of alcohol on human brain development are limited. Most of our data come from animal models and associations with alcohol exposure.

Scientists do know that alcohol is a teratogen that causes irreversible damage to the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). From associations with alcohol exposure, we are aware that that damage is widespread, causing not only a decrease in brain volume but also damage to structures within the brain. We also know from associations that high levels of alcohol consumption in the first trimester resulted in an increased likelihood of facial and brain anomalies. High levels of alcohol consumption in the second trimester are associated with increased incidences of spontaneous abortions. Lastly, in the third trimester, high levels of alcohol consumption are associated with decreased height, weight, and brain volume. Associations with alcohol exposure show that the neurobehavioral deficits associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders can occur within a wide range of exposure to alcohol and at any point in the pregnancy.

From animal models, we know that prenatal alcohol exposure affects all stages of brain development through a variety of mechanism, the most significant of which result in cognitive, motor, and behavioral dysfunction.

According to an article by Zhang et al., in the November 5, 2017 issue of Toxicology Letters, animal research that exposed the chick embryo to alcohol may help to understand the exact etiology of brain injury in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. The cranial neural crest cells contribute to the formation of the craniofacial bones. Exposure to 2% ethanol (alcohol) induced craniofacial defects in the developing chick fetus. Immunofluorescent staining revealed that ethanol treatment downregulated Ap-2, Pax7, and HNK-1 expressions by cranial neural crest cells. The use of double-immunofluorescent stainings for Ap-2/pHIS3 and Ap-2/c-caspase 3 showed that alcohol treatment inhibited cranial NCC proliferation and increased neural crest cell apoptosis. Alcohol exposure of the dorsal neuroepithelium increased laminin, N-cadherin, and cadherin 6B expressions while Cadherin 7 expression was repressed. In situ hybridization also revealed that ethanol treatment up-regulated cadherin 6B expression but down-regulated slug, Msx1, FoxD3, and BMP4 expressions, thus affecting proliferation and apoptosis.

Risk factors for FASD

- Women more than age 30 with a long history of alcohol are more likely to give birth to an infant with fetal alcohol syndrome

- Poor nutrition

- Having one child with fetal alcohol syndrome increases the risk for subsequent children

- Women with genetic susceptibility may metabolize alcohol slowly may be at a higher risk.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder symptoms

Because prenatal alcohol exposure has multiple effects on multiple organ systems, history, and physical findings associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders vary widely. In general, diagnoses within fetal alcohol spectrum disorders have one or more of the following features: abnormal facies, central nervous system abnormalities, and growth retardation. However, the different conditions under fetal alcohol spectrum disorders have different diagnostic criteria, and some require documentation of maternal alcohol use during pregnancy.

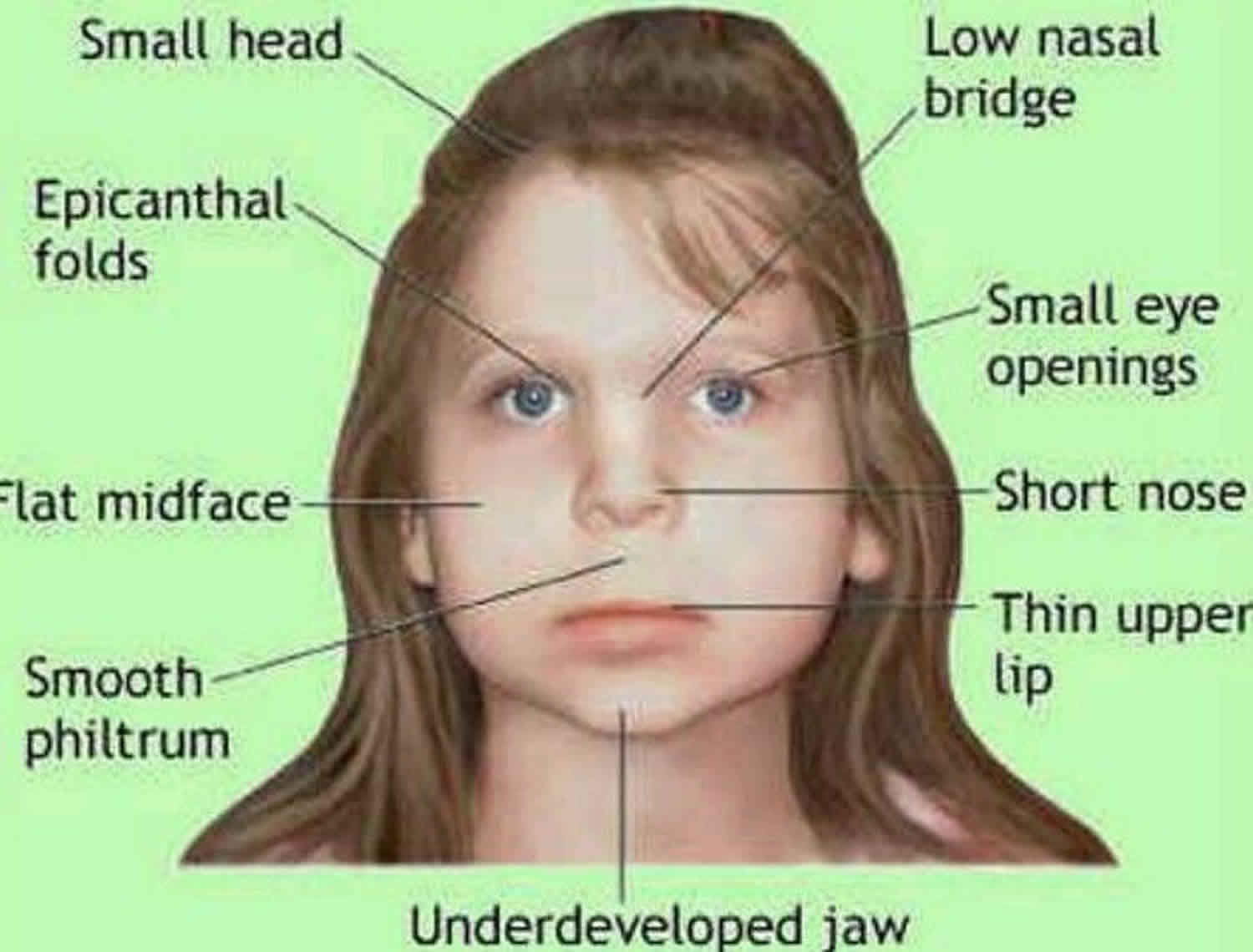

In general, the physical findings that should raise the index of suspicion for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are the characteristic facial features of short palpebral fissures, thin vermillion border, and a smooth philtrum. In-utero and postnatal growth retardation and microcephaly are also highly prevalent in children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Other common physical features that are associated with but not diagnostic of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders are maxillary hypoplasia, micrognathia, decreased interpupillary distance, among many others. Structural defects may also occur in the cardiovascular, renal, musculoskeletal, ocular, and auditory systems.

Like the physical findings, the central nervous system system deficits associated with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders can vary widely. They can range from irritability, jitteriness, and developmental delays in infancy to hyperactivity, inattention, and learning disabilities in childhood that can be misdiagnosed as simple attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In adolescence, the central nervous system abnormalities can manifest themselves in a number of ways from poor coordination, abnormal reflexes, poor academic performance, impaired problem-solving, poor social skills, deficiencies in executive functions such as cognitive planning and concept formation, poor understanding of consequences of actions, difficulties with the activities of daily living and problems with impulse control which can manifest, disrupting school, inability to maintain employment, or inappropriate sexual behavior.

The history that is associated with undiagnosed fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is fairly wide. In neonates, it is crucial to get a good prenatal history to determine prenatal alcohol exposure. For older children and young adults, the primary indicative history will be those areas pertaining to neurocognitive and behavioral impairment. Their history will point to the fact that those with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders have a high incidence of emotional and behavioral problems. Past experience with the juvenile justice system or foster care system, having a sibling with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, recurrent unemployment, a history of substance abuse, and a history of inappropriate sexual behaviors such as improper touching and inappropriate exposure are some of the history findings that should raise the index of suspicion for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

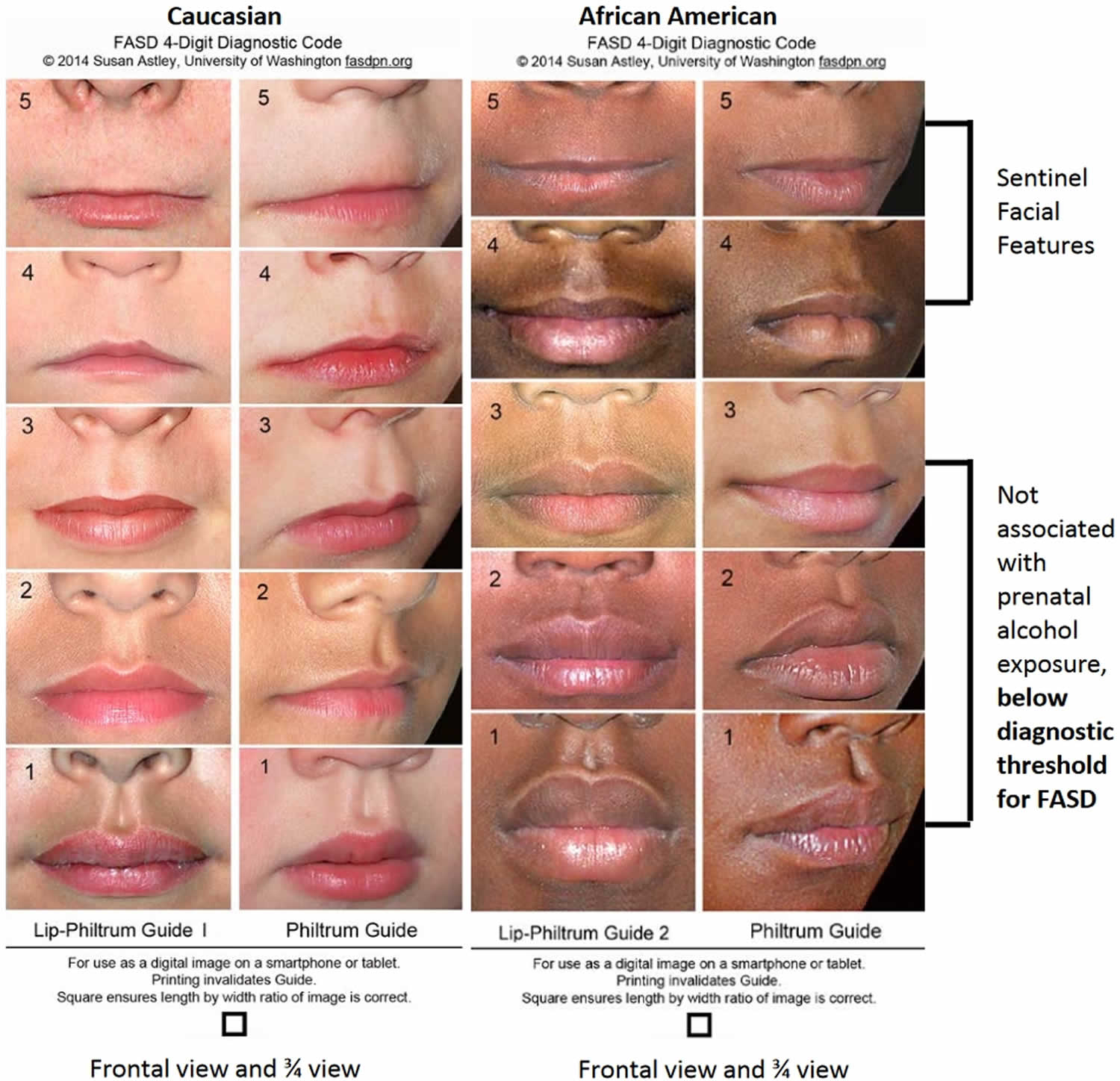

Figure 1. Lip philtrum guide

How will I know if my child has been affected by alcohol?

FASD is known as a ‘hidden harm’ because it is a physical brain-based condition that often goes undetected. Sometimes the harm is put down to other conditions.

FASD might not be obvious when your baby is born, and it’s only as your child gets older that behavioral and learning difficulties become noticeable.

If you drank during your pregnancy and your school-aged child has ‘problem’ behaviors, you may want to look into FASD. Identifying FASD early is important in helping to manage a lifelong condition.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder diagnosis

The diagnosis of FASD is complex, and ideally requires a multidisciplinary team of clinicians to evaluate individuals for prenatal alcohol exposure, neurodevelopmental problems and facial abnormalities in the context of a general physical and developmental assessment. Alternative diagnoses must be considered, including genetic diagnoses and exposure to other teratogens. FASD may co-exist with these and other conditions. The impact on neurodevelopment of both physical and psychosocial postnatal exposures such as early life trauma must also be considered.

When evaluating a patient for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, each of the five conditions that comprise fetal alcohol spectrum disorders has specific diagnostic criteria.

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is diagnosed by the presence of all of the following criteria: two of the three characteristic facial features (short palpebral fissures, thin vermillion border, and a smooth philtrum), growth retardation (prenatally and/or postnatally), and central nervous system defects. Because all of these criteria are met for diagnosis, fetal alcohol syndrome does not require documentation of prenatal alcohol exposure. Partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS) has two of the characteristic facial features plus, depending on where alcohol exposure was documented, varies in its other criteria. Alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD) is the term used to describe those with the physical defects secondary to known fetal alcohol exposure, but who do not have neurobehavioral deficits. On the opposite end of the spectrum, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) describes those with neurobehavioral impairment in the setting of documented prenatal alcohol exposure but have minimal to no physical findings and cannot be diagnosed before three years of age. Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE) is very similar to alcohol-related congenital disabilities but may involve some physical features.

Because of the wide-ranging presentation and large overlap with other genetic and environmental etiologies such as illicit drug and tobacco use, a primary care provider cannot make a definitive diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Once a primary care provider has a strong suspicion for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, their patient should be referred to a team of specialists to rule out other possible conditions and make a definitive diagnosis.

The composition diagnostic team varies based on the age of the patient. In general, the diagnostic team includes a pediatrician and/or physician who may have expertise in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, an occupational therapist, speech language pathologist, and psychologist.

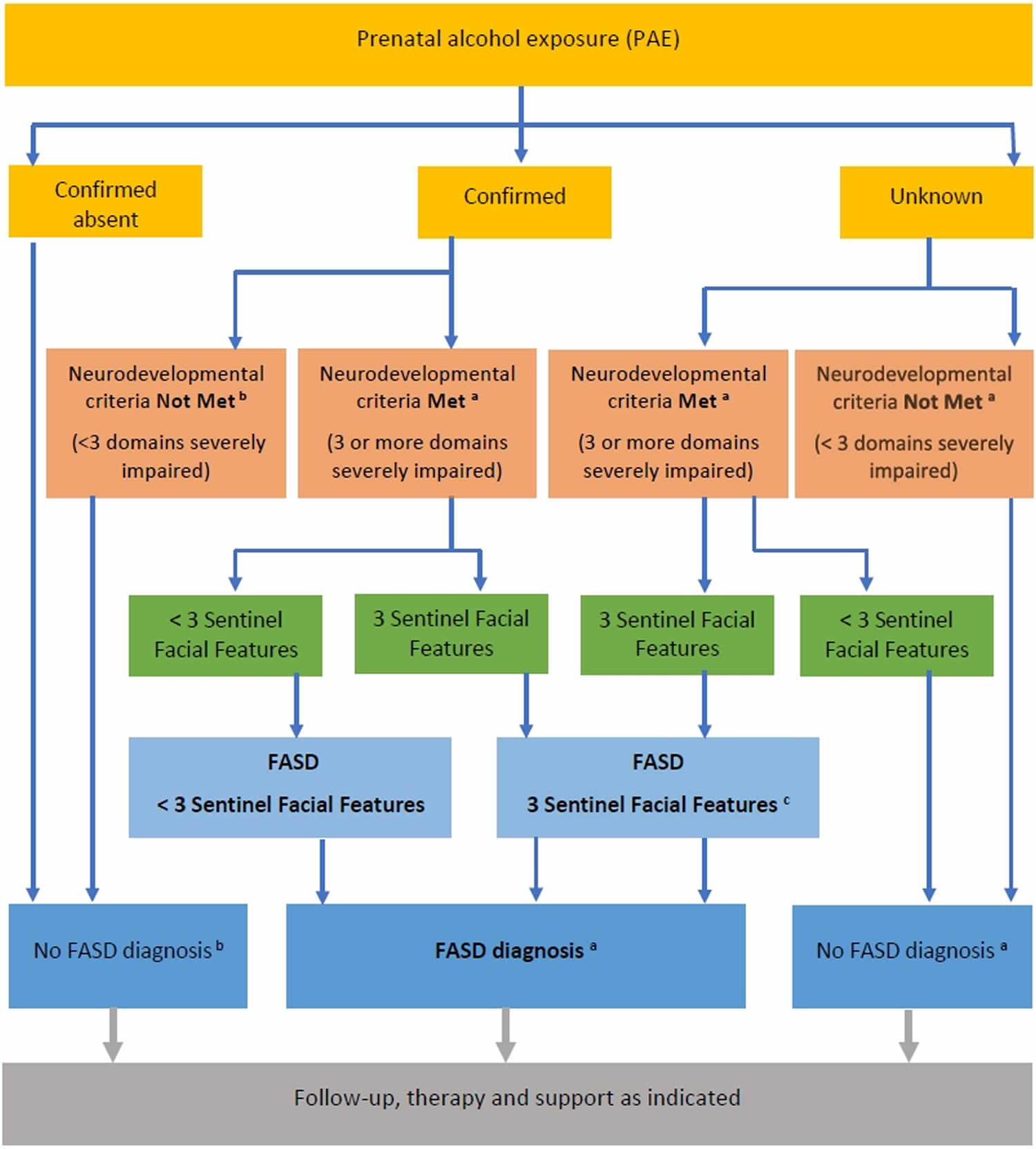

Figure 2: Diagnostic algorithm for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

Footnote:

a) Assessment fully completed and other diagnoses have been considered. Currency of assessment is also assumed. For infants and children under 6 years of age, severe Global Developmental Delay meets criteria for neurodevelopmental impairment (in 3 or more domains) if it is confirmed on a standardised assessment tool (e.g. Bayley or Griffiths).

b) In the presence of confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure, reassessment of neurodevelopmental domains can be considered as clinically indicated (e.g. if there is a decline in an individual’s functional skills or adaptive behaviour over time).

c) In infants and young children under 6 years of age with microcephaly and all 3 sentinel facial features, a diagnosis of FASD with 3 Sentinel Facial Features can be made, whether prenatal alcohol exposure is confirmed or unknown, even without evidence of severe neurodevelopmental impairment in 3 domains based on standardised assessment.

Nonetheless, in these children, concerns about neurodevelopmental impairment are likely to be present and should be documented.

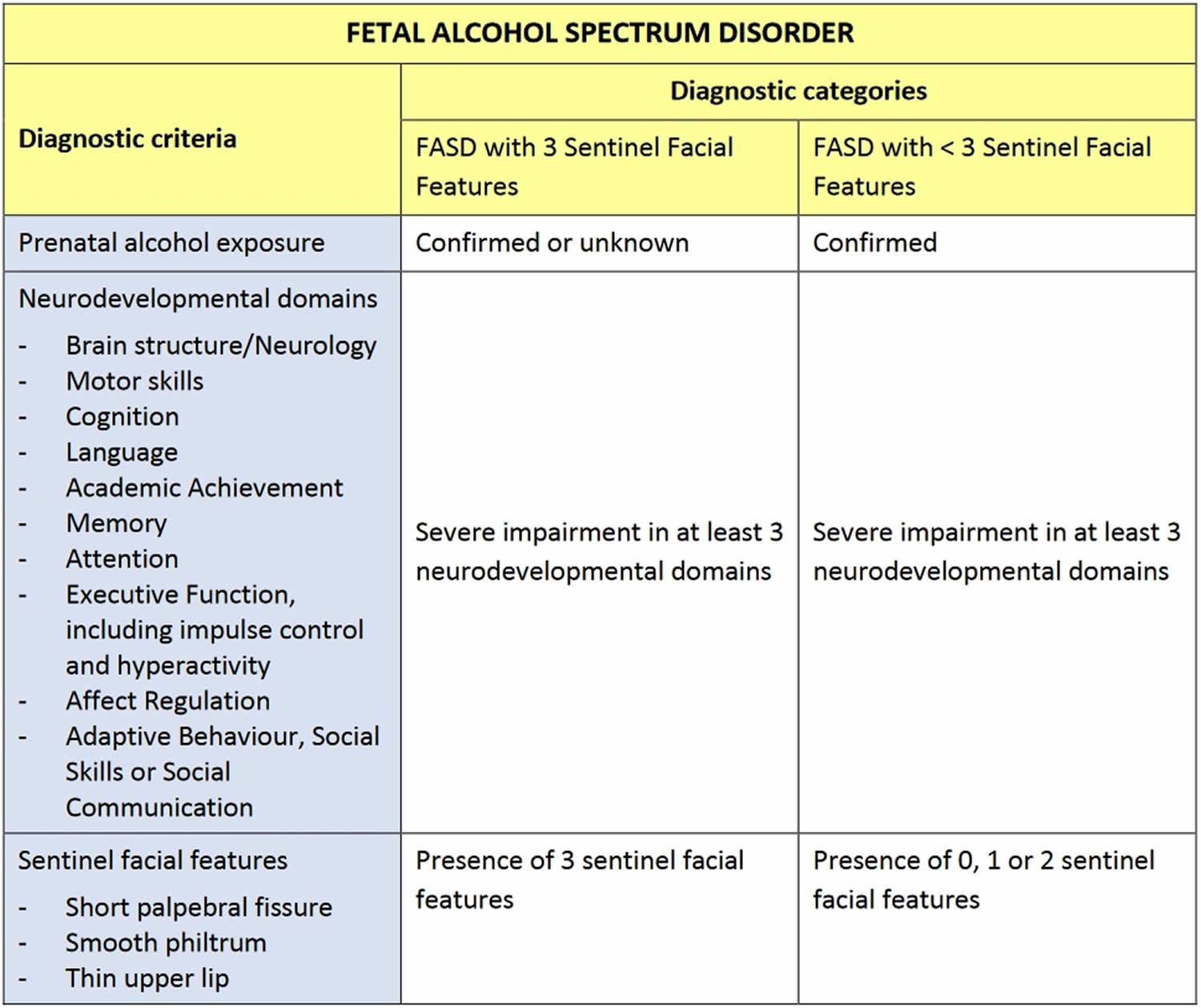

[Source 5 ]Diagnostic categories and criteria for FASD

A diagnosis of FASD requires evidence of prenatal alcohol exposure and severe impairment in three or more domains of central nervous system structure or function 5.

A diagnosis of FASD can be divided into one of two sub-categories:

- FASD with three sentinel facial features

- FASD with less than three sentinel facial features

The diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1.

FASD with three sentinel facial features replaces the diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, but without a requirement for growth impairment. FASD with less than three sentinel facial features encompasses the previous categories of Partial Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Neurodevelopmental Disorder-Alcohol Exposed) 6.

The etiological role of alcohol is most clearly established in the presence of all three characteristic facial abnormalities. In this situation a diagnosis of FASD with three sentinel facial features can be made even when prenatal alcohol exposure is unknown 7, provided there is also severe neurodevelopmental impairment.

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria and categories for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

[Source 5 ]Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder treatment

Given that the central nervous system damage from prenatal alcohol exposure is permanent, there is no cure for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. However, treatment to mitigate the effects of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is available. Given the extensive variation in presentation and damage that prenatal exposure to alcohol can cause, treatment for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders is often tailored and specific to individuals. One of the most common treatment approaches is using the medical home to coordinate developmental and educational resources. This treatment modality takes into account the fact that fetal alcohol spectrum disorders disrupt normal neurobehavioral development and that each person can have different manifestations of those disruptions. This treatment methodology seeks to tailor specific therapies to reinforce and address any delays or deficiencies with additional education, practice, and reminders. In summary, when it comes to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, as is true of most conditions in medicine, the best treatment is prevention 8.

Listed below are evidence-based intervention programs specific to managing and working with children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

| Program | Description |

|---|---|

| Math Interactive Learning Experience (MILE) | The MILE program demonstrates the effectiveness of adaptive materials and tutoring methods to improve math knowledge and skills in children with FASDs. |

| Good Buddies | Good Buddies is a group program for children with FASDs and their parents shown to improve peer interactions, social skills, and parent understanding of FASD-related disabilities. |

| Parents and Children Together (PACT) | PACT is a group program designed to improve behavior regulation skills, executive functioning, and parent effectiveness. |

| Families Moving Forward (FMF) | The FMF program is a positive parenting intervention designed to help families raising children between 4 and 12 years old who have behavior problem and FASD (or were heavily alcohol exposed). The FMF program model is a behavioral consultation intervention that combines a positive behavior support approach with motivational interviewing and other scientifically validated treatment techniques. |

| Language to Literacy Program | This classroom-based program provides instruction to improve receptive and expressive language skills as well as early literacy skills. |

| USFA Kids | This is a computer-based program that teaches and reinforces basic safety skills. |

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder prognosis

Besides affecting the fetus, alcohol can induce the risk of spontaneous abortions, preterm delivery, placental abruption, stillbirth, and amnionitis.

Prognosis is guarded; however, recent research with chick embryos may help guide future treatments to reverse the damage caused to the brain by prenatal alcohol exposure.

References- Vorgias D, Bernstein B. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Dec 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448178

- Bukiya AN. Fetal Cerebral Artery Mitochondrion as Target of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 May 07;16(9).

- Roozen S, Peters GY, Kok G, Townend D, Nijhuis J, Koek G, Curfs L. Systematic literature review on which maternal alcohol behaviours are related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). BMJ Open. 2018 Dec 19;8(12):e022578

- Popova S, Lange S, Shield K, Burd L, Rehm J. Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among special subpopulations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2019 Jul;114(7):1150-1172.

- Bower C, Elliott EJ 2016, on behalf of the Steering Group. Report to the Australian Government Department of Health: “Australian Guide to the diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)”. https://www.fasdhub.org.au/siteassets/pdfs/australian-guide-to-diagnosis-of-fasd_all-appendices.pdf

- Watkins RE, Elliott EJ, Wilkins A, Mutch RC, Fitzpatrick JP, Payne JM, et al. Recommendations from a consensus development workshop on the diagnosis of *fetal* *alcohol* spectrum disorders in Australia. BMC PEDIATRICS. 2013;13:156.

- Astley SJ. Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: The 4-Digit Diagnostic Code. Third ed. Seattle: University of Washington; 2004.

- Brown JM, Bland R, Jonsson E, Greenshaw AJ. The Standardization of Diagnostic Criteria for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): Implications for Research, Clinical Practice and Population Health. Can J Psychiatry. 2019 Mar;64(3):169-176.