Fat necrosis

Fat necrosis is a benign (non-cancerous) breast condition that happens when an area of the fatty breast tissue is damaged, usually as a result of injury to the breast. Breast fat necrosis can also happen after breast surgery or radiation treatment. Fat necrosis is more common in women with very large breasts 1. Breast fat necrosis is a benign inflammatory process and is becoming increasingly common with the greater use of breast conserving surgery and mammoplasty procedures. Most at risk are middle-aged women with pendulous breasts. The onset of fat necrosis can be considerably delayed, occurring 10 years or more after surgery 2.

Fat necrosis is a sterile, inflammatory process which results from aseptic saponification of fat employing blood and tissue lipase 3. Lipase is an enzyme that releases fatty acids from triglycerides. These fatty acids form a complex with calcium to form saponification. The age of the lesion in fat necrosis dictates its appearance both grossly and microscopically.

At a microscopic level, the initial change is disruption of fat cells where vacuoles with the remnants of necrotic fat cells are formed. They then become surrounded by lipid-laden macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and acute inflammatory cells. Fibrosis develops during the reparative phase peripherally enclosing an area of necrotic fat and cellular debris. Eventually, fibrosis may replace the area of degenerated fat with a scar, or loculated and degenerated fat may persist for years within a fibrotic scar.

Fat necrosis first appears as an area of hemorrhage in fat, which manifests as induration and firmness on gross pathology. Subsequently saponification occurs, where the lesion may become yellow, then calcification, which presents as a chalky white lesion, and lastly fibrosis, a yellow-gray mass. Scar formation is the result of reactive inflammatory components eventually replaced by fibrosis. Additionally, some adipose cells will release their contents instead of forming scars as a result of injury, and this is known as cystic degeneration. Calcifications frequently develop around the outer lining of the cyst. Fibrosis can surround degenerated fat or oil (known as “oil cyst”), which may persist for months or years.

The incidence of breast fat necrosis overall is roughly 0.6%, representing 2.75% of all benign lesions 4. Fat necrosis presents in 0.8% of breast tumors and 1 to 9% of breast reduction surgery cases. Most at risk are middle-aged women, with an average age of 50 years, and women with pendulous breasts 3.

Fat necrosis can be diagnosed clinically or radiographically in the majority of cases, without the need for biopsy 5. In surgical patients who have recently undergone a breast surgical procedure such as breast reduction, reconstruction, implant removal, or fat grafting after primary reconstruction, the most common presentation is the finding of a palpable mass or lump under the breast skin. There is a predilection for the subareolar and periareolar regions, but it can occur anywhere. Detection through imaging without an obvious source, such as recent surgery or trauma, or when associated with findings such as lymphadenopathy or skin change, requires exclusion of malignancy.

Figure 1. Fat necrosis breast ultrasound

Footnote: 72 year old female with breast fat necrosis with an irregular mass after surgery mimicking breast cancer.

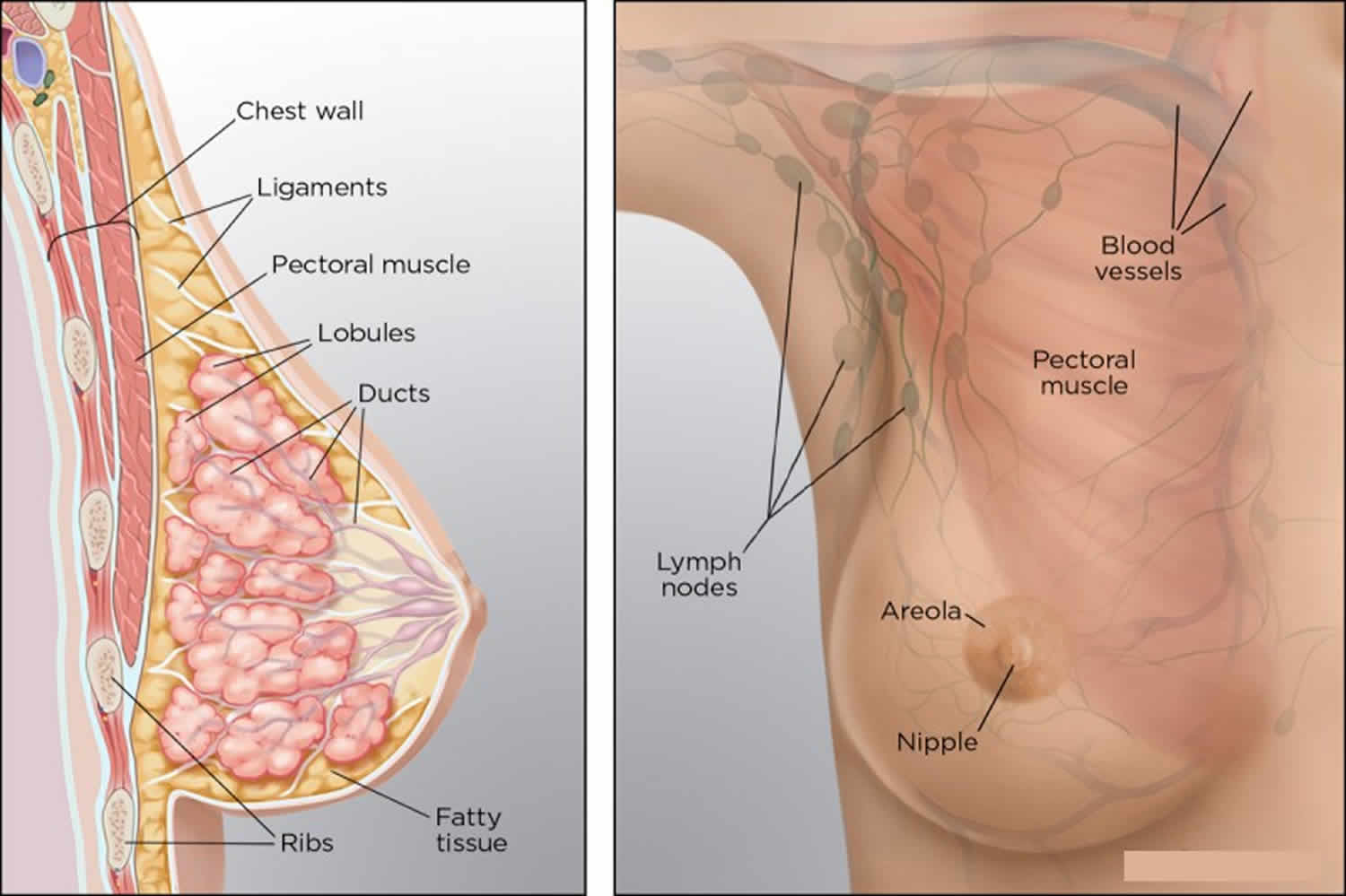

Breast anatomy

Three structures comprise the breast: skin, subcutaneous tissue, and breast tissue. The breast tissue contains both epithelial and stromal elements, the latter being both adipose and fibrous connective tissue. Stromal elements are responsible for the majority of breast volume during the non-lactating state.

The majority of the blood supply to the breast comes from the internal mammary artery perforators and the minority from the lateral thoracic artery perforators. This factor is essential, especially during breast reduction and/or reconstruction, where transection of vessels and subsequent relative ischemia can lead to breast fat necrosis.

Lymphatic drainage follows a unidirectional flow, from deep subcutaneous and intramammary vessels, towards axillary and internal mammary lymph nodes. Although the majority of the blood supply comes from the internal mammary artery, only 4% lymph flows go to internal mammary nodes, with the majority (97 percent) of the lymph flows to the axillary nodes.

Figure 2. Female breast anatomy

Fat necrosis breast

Breast fat necrosis is nonviable fat cells from injured or ischemic breast tissue that is replaced with scar tissue and presents as a palpable nodule 5. Breast fat necrosis has various causes and implications; therefore, a careful patient history is imperative to properly evaluate the patient. The most common cause of fat necrosis is recent breast surgery; however, in non-operative patients, cancer or mechanical trauma to the breast tissue is often the culprit 5. Breast fat necrosis can be confusing on breast imaging with cancer, it can mimic malignancy on radiologic studies, as well as clinical presentation. It can also be cosmetically undesirable.

Breast fat necrosis causes

Fat necrosis is most commonly the result of breast trauma (21 to 70%), fine needle aspiration or biopsy, anticoagulation treatment, radiation, and breast infection 3. In everyday clinical practice, trauma and surgery are the most common cause of breast fat necrosis. Individual patient factors such as smoking, obesity, and older age, as well as treatment associated with breast cancer (radiation, chemotherapy, and mastectomy), are specifically associated with an increase in breast fat necrosis 6. Breast fat necrosis can have an association with any breast surgical procedure; however, it becomes the prime concern after mastectomy/reconstruction as fat necrosis can cause breast deformity or concern for cancer recurrence.

Fat necrosis after breast reconstruction

The free flap has gained favor for breast reconstruction after mastectomy over the past several decades. A flap a transfer of tissue with its blood supply from one part of the body to another. After a partial or total mastectomy, this process is autologous breast reconstruction, and this can be by pedicled or free tissue transfer. In pedicled tissue transfer, the blood supply is kept intact, and the tissue flap is tunneled or rotated to the recipient site. In a free flap, the vessels get disconnected during the transfer, thus making it “free,” and then reconnected microsurgically to a new artery and vein at or near the recipient site. Deep inferior epigastric perforator flap is the current mainstream choice for breast free flap.

The creation of a flap is complex and requires a substantial level of training, planning, and surgical expertise. Many factors lead to fat necrosis in flap reconstruction. However, the cause of the problem is ischemia – either inadequate arterial inflow or poor venous outflow can cause ischemia and subsequent fat necrosis of the flap itself. Many studies have demonstrated the association of breast fat necrosis in free flap reconstruction with the number of perforators and flap weight 7. This outcome is intuitive – as the ratio of blood supply to surface area increases, there is more perfusion to fat tissue and less chance of ischemia. Additionally, suggestions are that a greater amount of venous outflow with additional venous anastomoses decreases the incidence of breast fat necrosis 8. Other factors shown to increase the incidence of breast fat necrosis in free flaps include smoking, pedicle caliber, type of flap, radiation, and surgeon’s experience 9. Many surgeons require patients to quit smoking 8 weeks prior to surgery.

Fat necrosis after breast reduction or lumpectomy

There are many techniques described to reduce breast size, based on incision and pedicle types. Breast reduction is also possible by liposuction alone, but that is mainly reserved for young women with high expected skin elasticity. The pedicle is the area of the adipose tissue supplied by one or many arterial perforators which branch into smaller capillaries. If blood supply is disrupted significantly, especially in distal areas of the pedicle and overlying skin, then fat necrosis can occur. The amount of breast tissue excised directly correlates to the complication rate 10. The incidence of fat necrosis in breast reduction is found to be between 1 to 9% 11. Tobacco smoking is a known independent factor in the increased risk for fat necrosis and other complications after breast reduction 12.

Fat Grafting

Fat grafting is done by harvesting fat using liposuction from one part of the body and injecting it to another. Fat grafting can be especially useful in the management of contour deformity in breast reconstruction, known as a “step-off deformity,” or the point where the breast reconstruction (implant or flap) transitions to the native chest wall. Additionally, fat grafting can improve surrounding skin quality after radiation or skin-sparing mastectomy, decrease implant visibility in a patient with minimal subcutaneous fat or minimal native breast tissue, and fill in defects caused by the excision of previous breast fat necrosis.

Fat necrosis is a commonly seen result after fat grafting, as the blood supply to fat grafted is random and acquired from surrounding tissues by diffusion and neovascularization. Although multiple fat grafting techniques have undergone evaluation, there is no consensus on superiority amongst them 13. Regardless of the techniques, the reported rates of fat necrosis after fat grafting is between 2% and 18% 14. No one variable such as age, body mass index, stage of malignancy, smoking, radiation, harvest site or technical variables (fat/tumescent volume, syringe aspiration vs. liposuction pump, cannula type or size) was found to predict the development of fat necrosis 15. However, studies do show adipocyte destruction directly correlates with time spent ex vivo; therefore, lipotransfer should occur as promptly as possible after fat harvest 16.

Fat necrosis after mastectomy

Breast fat necrosis after mastectomy often occurs due to small amounts of adipose tissue without blood supply being left behind, causing ischemia-related necrosis. The mass is often palpable, and the differential diagnosis includes fat necrosis, fibrocystic disease, hematoma or seroma, suture or dermal calcifications, scar tissue, edema, abscess, and, more concerning, recurrent or new breast cancer 17. Timing is important in the evaluation of these patients as local recurrence of malignancy tends to occur in the first 1 to 5 years after surgery, whereas most of these changes of fat necrosis happen within weeks to months after surgery.

Fat necrosis after radiation therapy

Flaps experience a higher rate of fat necrosis when irradiated. The rate of symptomatic fat necrosis in brachytherapy and now accelerated partial breast irradiation is found to be 1 to 50% 18. The incidence is related to volume encompassed by the given dose of radiation or how much tissue was irradiated by the maximum strength of radiation prescribed 19. There is some evidence that interstitial brachytherapy may cause additional trauma due to the implanted needle, causing an increased incidence of fat necrosis 19. Studies have also shown an increase in breast fat necrosis with brachytherapy in populations who also received treatment with adriamycin-based chemotherapy 20.

Breast fat necrosis symptoms

Areas of fat necrosis can form a lump that can be felt, but it usually doesn’t hurt. The skin around the lump might look thicker, red, or bruised. Sometimes these changes can be hard to tell apart from cancers on a breast exam or even a mammogram. If this is the case, a biopsy (removing all or part of the lump to look at the tissue under the microscope) might be needed to find out if the lump contains cancer cells.

Features associated with breast fat necrosis include an irregular breast mass, usually fixed to the dermis, with possible skin tethering and/or nipple retraction as a result of fibrotic bands between necrotic tissue and skin. These same characteristics can also be hallmark findings of cancer, thus making it essential to consider all patient factors.

Doctors can usually tell a fat necrosis by the way it looks on an ultrasound. But if there’s a concern that it might be something else, a needle aspiration biopsy might be done, in which a thin, hollow needle is put into the cyst to take out the fluid for testing.

A careful history is paramount to the diagnosis of breast fat necrosis. Although malignancy should always be in the differential, efforts should be made to spare the patient from the unnecessary emotional and financial burden of unnecessary procedures. Additionally, invasive work-up such as core biopsy can be detrimental to some patient populations such as those with irradiated breast, where a non-healing wound may develop.

- History of trauma (i.e., motor vehicle crash with a person restrained by a seatbelt)

- History of breast surgery/reconstruction

- History of breast implant removal

- History of breast radiation

- Obesity with very large breasts

- Pendulous breasts

Breast fat necrosis complications

Breast fat necrosis can occur early in the post-operative period or have a delayed presentation. Complications related to breast fat necrosis include pain, infection, need for multiple operations, and breast deformity. These complications can exert a profound effect on the patient, both physically and emotionally. Therefore, these are risks that should be discussed with the patient pre-operatively. There is no known risk for transformation to breast cancer 5.

Breast fat necrosis diagnosis

Once the surgeon finds a breat mass, he may reassure the patient or perform further evaluation. Essentially, the goal of the workup is to rule out breast cancer. The extent of the evaluation required to accomplish this goal varies based on the chief complaint, patient’s age, and risk factors. Workup is as follows:

- A thorough breast examination

- A mammogram, +/-ultrasound, +/- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Fine needle aspiration or core biopsy or excisional biopsy

Mammographic features

At mammography, fat necrosis may demonstrate the typical appearance of a cyst, which has a typical appearance of a smooth-bordered lucent mass. However, it is possible, based on the level of fibrosis, that fat necrosis will manifest as a cluster of pleomorphic microcalcifications, with areas of abnormal opacity, making it hard to differentiate from malignancy 21.

Sonographic features

Fat necrosis or oil cyst, when seen on ultrasound is a cystic lesion with echogenic internal bands, and its orientation is affected by the patient’s body position. In non-cystic lesions including fat necrosis, common features include increased echogenicity of subcutaneous tissue (27%), anechoic cyst with posterior acoustic enhancement (17%), hypoechoic mass with posterior acoustic shadowing (16%), solid mass (14%), or normal appearance (11%) 3. Doppler ultrasound can also help make the diagnosis of fat necrosis and rule out malignancy by failing to demonstrate internal vascularity to the mass in question. Overall, ultrasound is less specific, and therefore, mammography is preferred when making the radiologic diagnosis of fat necrosis. However, it can still be a useful tool in ruling out malignancy.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI is used to differentiate breast fat necrosis from carcinoma when there is prnounced fibrosis, and the lesion presents as a spiculated infiltrative mass with or without microcalcification. MRI has been reported to have a negative predictive value approaching 100% in patients with a history of breast surgery 22. Fat necrosis usually looks identical to adjacent fat on MRI, and there is no enhancement after IV contrast. The exception to that is enhancement seen up to 6 months from surgery in fresh granulation tissue, making MRI slightly less reliable. If that occurs, the use of fat suppression can aid in the differentiation from a tumor. Other MRI findings are signal void in areas of calcifications and architectural distortion in tissue fibrosis. The most common MRI finding in fat necrosis is a round or oval hypointense mass on T1-weighted signal on fat saturation images, confirming the presence of an oil cyst.

The presentations of breast necrosis vary on mammography, ultrasound, and MRI. In one study, however, it was found that diangosis of calcifications was best by mammography, oil cysts by ultrasound, and fibrotic fat necrosis by MRI 23. Knowledge of the possibility of sonographic findings, along with mammographic features, may aid the clinician in determining whether further investigation is necessary.

Fine needle aspiration

Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) has high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing fat necrosis, offering an alternative to biopsy 24. The cytology ranges from clumped fat lobules with opaque cytoplasm to necrotic aspirate with dispersed fat cells with opaque cytoplasm, foamy macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. However, sampling error and incomplete biopsy can be a problem, leading to repeat attempts. In combination with a reliable history such as trauma or recent surgery and close clinical follow-up, FNA is a good option.

Core biopsy

Core biopsy is more sensitive than FNA, and the accuracy of a large-bore core biopsy is said to be comparable to excisional biopsy for diagnosis of fat necrosis in low-risk patients 25. However, if the radiologic findings strongly support fat necrosis, then the biopsy can be avoided altogether. Core biopsy has been shown to have a slightly higher rate of false negative results in high-risk patients, and excisional biopsy may be needed to confirm fat necrosis.

Excisional biopsy

If suspicion for malignancy is high, and core biopsy is negative, excisional biopsy is the next diagnostic step.

Breast fat necrosis treatment

Palpable areas of fat necrosis may enlarge, remain unchanged, regress, or resolve 5. Fat necrosis breast usually does not necessitate any surgical treatment, and clinical follow-up is sufficient in the patient population in which pain is not present, and cosmesis is not the primary concern 5. However, if fat necrosis is confirmed, and it does not resolve and/or it causes pain or distortion in the breast shape, surgical removal is an option. As far as mammography is concerned, a lesion classified as “benign” by mammogram may undergo yearly surveillance. A finding of “most likely benign” can be followed up in 6 months with a mammogram, and a biopsy is a next step if “malignancy suspected.”

If the fat necrosis contains oily fluid, it may need to be aspirated using a needle to relieve any patient discomfort. In the case of a solid mass and/or breast distortion, treatment options depend on the size of the anticipated defect after excision. A small defect may be addressed with either excision alone or excision with fat grafting and/or local tissue rearrangement. For a large defect such as those due to partial flap loss after reconstruction, a more significant tissue debridement and reconstruction may be necessary. In those cases, the patient may opt for a secondary free flap or other tissue transfer, convert to tissue expanders or breast implants to increase volume, or undergo a contralateral symmetry procedure to achieve symmetry.

Breast fat necrosis prognosis

The main concern associated with the diagnosis of breast fat necrosis is the similarity in presentation, both clinical and radiologic, to breast cancer. Fortunately, breast fat necrosis is a benign process with an excellent prognosis. It does not increase the risk of future breast cancer development in any way 5.

References- Breast Imaging Case of the Day. Dvora Cyrlak and Philip M. Carpenter. RadioGraphics 1999 19:suppl_1, S80-S83 https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.19.suppl_1.g99se24s80

- Pope TL. Aunt Minnie’s Atlas and Imaging-Specific Diagnosis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (2008) ISBN:0781787815

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, Opaluwa AS, Ravikumar KH, Chetty N, Kaplan V, Kelley CJ, Babu ED. Fat necrosis of the breast–a review. Breast. 2006 Jun;15(3):313-8.

- Kerridge WD, Kryvenko ON, Thompson A, Shah BA. Fat Necrosis of the Breast: A Pictorial Review of the Mammographic, Ultrasound, CT, and MRI Findings with Histopathologic Correlation. Radiol Res Pract. 2015;2015:613139

- Genova R, Waheed A, Garza RF. Breast Fat Necrosis. [Updated 2019 Jun 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542191

- Selber JC, Kurichi JE, Vega SJ, Sonnad SS, Serletti JM. Risk factors and complications in free TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2006 May;56(5):492-7.

- Baumann DP, Lin HY, Chevray PM. Perforator number predicts fat necrosis in a prospective analysis of breast reconstruction with free TRAM, DIEP, and SIEA flaps. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010 May;125(5):1335-41.

- Ochoa O, Pisano S, Chrysopoulo M, Ledoux P, Arishita G, Nastala C. Salvage of intraoperative deep inferior epigastric perforator flap venous congestion with augmentation of venous outflow: flap morbidity and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013 Oct;1(7):e52

- Kaidar-Person O, Eblan MJ, Caster JM, Shah AR, Fried D, Marks LB, Lee CN, Jones EL. Effect of internal mammary vessels radiation dose on outcomes of free flap breast reconstruction. Breast J. 2019 Mar;25(2):286-289.

- Shestak KC, Davidson EH. Assessing Risk and Avoiding Complications in Breast Reduction. Clin Plast Surg. 2016 Apr;43(2):323-31.

- Ogunleye AA, Leroux O, Morrison N, Preminger AB. Complications After Reduction Mammaplasty: A Comparison of Wise Pattern/Inferior Pedicle and Vertical Scar/Superomedial Pedicle. Ann Plast Surg. 2017 Jul;79(1):13-16.

- Uslu A, Korkmaz MA, Surucu A, Karaveli A, Sahin C, Ataman MG. Breast Reduction Using the Superomedial Pedicle- and Septal Perforator-Based Technique: Our Clinical Experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019 Feb;43(1):27-35.

- Sinno S, Wilson S, Brownstone N, Levine SM. Current Thoughts on Fat Grafting: Using the Evidence to Determine Fact or Fiction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016 Mar;137(3):818-24.

- Delay E, Garson S, Tousson G, Sinna R. Fat injection to the breast: technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet Surg J. 2009 Sep-Oct;29(5):360-76.

- Doren EL, Parikh RP, Laronga C, Hiro ME, Sun W, Lee MC, Smith PD, Fulp WJ. Sequelae of fat grafting postmastectomy: an algorithm for management of fat necrosis. Eplasty. 2012;12:e53

- Matsumoto D, Shigeura T, Sato K, Inoue K, Suga H, Kato H, Aoi N, Murase S, Gonda K, Yoshimura K. Influences of preservation at various temperatures on liposuction aspirates. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007 Nov;120(6):1510-7.

- Scaranelo AM, Lord B, Eiada R, Hofer SO. Imaging approaches and findings in the reconstructed breast: a pictorial essay. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2011 Feb;62(1):60-72.

- Thomas MA, Ochoa LL, Zygmunt TM, Matesa M, Altman MB, Garcia-Ramirez JL, Esthappan J, Zoberi I. Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation: A Safe, Effective, and Convenient Early Breast Cancer Treatment Option. Mo Med. 2015 Sep-Oct;112(5):379-84.

- Lövey K, Fodor J, Major T, Szabó E, Orosz Z, Sulyok Z, Jánváry L, Fröhlich G, Kásler M, Polgár C. Fat necrosis after partial-breast irradiation with brachytherapy or electron irradiation versus standard whole-breast radiotherapy–4-year results of a randomized trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007 Nov 01;69(3):724-31.

- Wazer DE, Kaufman S, Cuttino L, DiPetrillo T, Arthur DW. Accelerated partial breast irradiation: an analysis of variables associated with late toxicity and long-term cosmetic outcome after high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006 Feb 01;64(2):489-95.

- Hogge JP, Robinson RE, Magnant CM, Zuurbier RA. The mammographic spectrum of fat necrosis of the breast. Radiographics. 1995 Nov;15(6):1347-56.

- Hassan HHM, El Abd AM, Abdel Bary A, Naguib NNN. Fat Necrosis of the Breast: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics and Pathologic Correlation. Acad Radiol. 2018 Aug;25(8):985-992

- Shida M, Chiba A, Ohashi M, Yamakawa M. Ultrasound Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Lumps after Breast Augmentation with Autologous Fat Grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017 Dec;5(12):e1603

- Brown LA, Coghill SB. Fine needle aspiration cytology of the breast: factors affecting sensitivity. Cytopathology. 1991;2(2):67-74.

- Parker SH, Burbank F, Jackman RJ, Aucreman CJ, Cardenosa G, Cink TM, Coscia JL, Eklund GW, Evans WP, Garver PR. Percutaneous large-core breast biopsy: a multi-institutional study. Radiology. 1994 Nov;193(2):359-64.