What is a fecal transplant

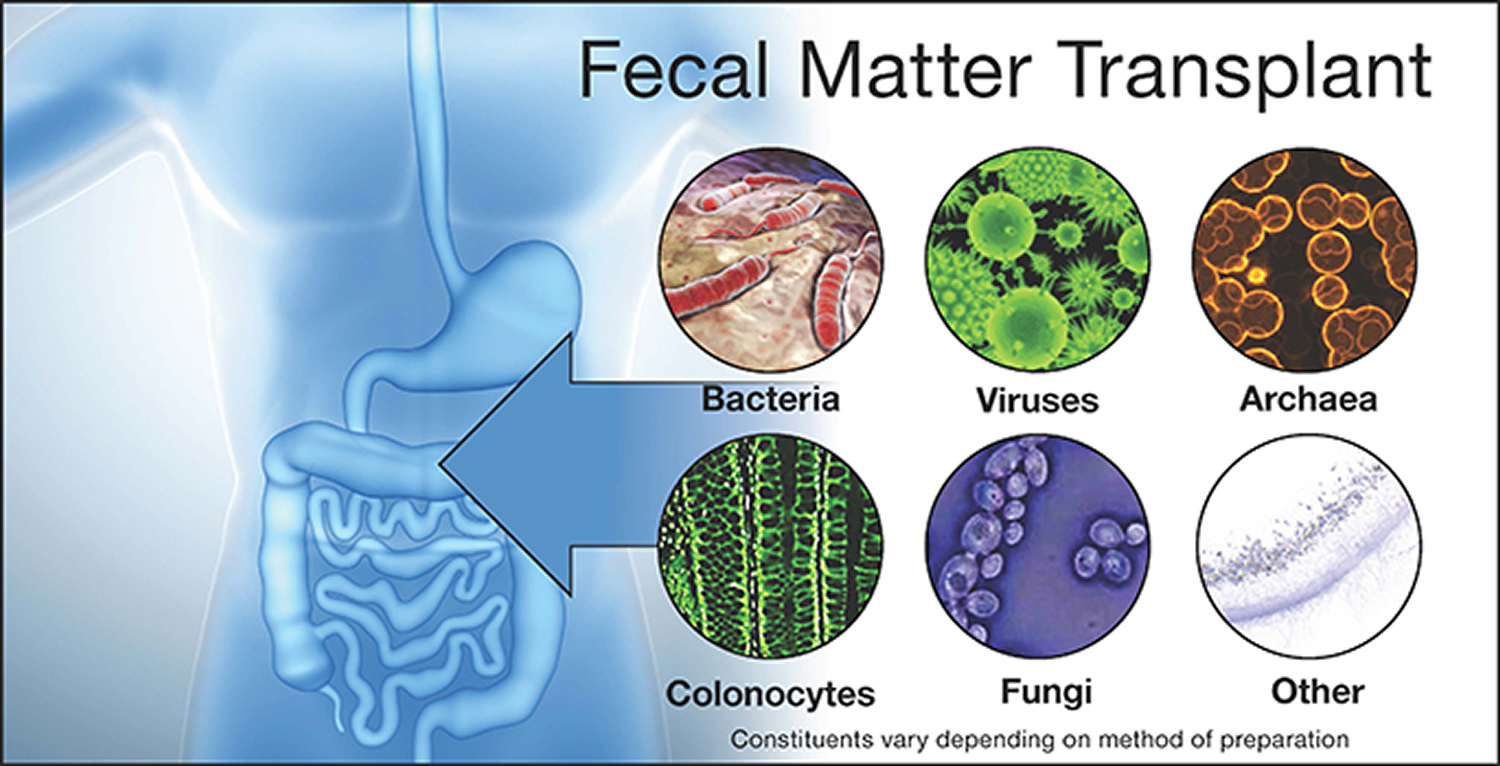

A fecal transplant is called fecal bacteriotherapy, involves the introduction of saline-diluted fecal matter from a donor into a patient’s gastrointestinal tract via a nasoduodenal catheter or enema, primarily to treat Clostridium difficile infection 1. The concept of fecal transplant to replace some of the “bad” bacteria of your colon with “good” bacteria. The procedure is supposed to help restore the good bacteria that has been killed off or limited by the use of antibiotics. Restoring this balance in the colon makes it easier to fight infection.

Fecal matter transplant involves collecting stool from a healthy donor. Your provider will ask you to identify a donor. Most people choose a family member or close friend. The donor must not have used antibiotics for the previous 3 months. They will be screened for any infections in the blood or stool.

Once collected, the donor’s stool is mixed with saline water and filtered. The stool mixture is then transferred into your digestive tract (colon) through a tube that goes through a colonoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a small camera).

The first “modern” use of fecal microbiota transplantation in humans was for the treatment of pseudomembranous colitis caused by Micrococcus pyogenes (Staphylococcus). It was given as fecal enemas and was reported in 1958 in a 4-patient case series by Eiseman and colleagues 2. Use of fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection was also by enema and first reported in 1983 by Schwan and colleagues 3. Until 1989, fecal retention enema was the most common technique for fecal microbiota transplantation 4; however, alternative methods of administration have been used subsequently, including fecal infusion via nasogastric tube (1991) 5, gastroscopy and colonoscopy (1998, 2000) 6 and self-administered enemas (2010) 7. To date, well over 500 cases of fecal transplant have been reported worldwide and include approximately 75% by colonoscopy or retention enema and 25% by nasogastric (or nasoenteric) tube or gastroduodenoscopy 8, 9.

For the last few decades, a small number of doctors have used the treatment as salvage therapy in North America. The treatment is slightly more popular in Scandinavia and published cases have emerged from approximately 20 sites around the world. They suggest fecal transplants can be life-saving for patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

Before the Fecal Transplant Procedure

The donor will likely take a laxative the night before the procedure so they can have a bowel movement the next morning. They will collect a stool sample in a clean cup and bring it with them the day of the procedure.

Talk to your provider about any allergies and all medicines you are taking. DO NOT stop taking any medicine without talking to your provider. You will need to stop taking any antibiotics for 2 to 3 days before the procedure.

You may need to follow a liquid diet. You may be asked to take laxatives the night before the procedure. You will need to prepare for a colonoscopy the night before fecal matter transplant. Your doctor will give you instructions.

Before the procedure, you’ll be given medicines to make you sleepy so that you won’t feel any discomfort or have any memory of the test.

After the Fecal Transplant Procedure

You will lie on your side for about 2 hours after the procedure with the solution in your bowels. You may be given loperamide (Imodium) to help slow down your bowels so the solution remains in place during this time.

You will go home the same day of the procedure once you pass the stool mixture. You will need a ride home, so be sure to arrange it ahead of time. You should avoid driving, drinking alcohol, or any heavy lifting.

You may have a low-grade fever the night after the procedure. You may have bloating, gas, flatulence, and constipation for a few days after the procedure.

Your provider will instruct you about the type of diet and medicines you need to take after the procedure.

Risks of fecal matter transplant

Risks of fecal matter transplant may include the following:

- Reactions to the medicine you are given during the procedure

- Heavy or ongoing bleeding during the procedure

- Breathing problems

- Spread of disease from the donor (if the donor is not screened properly, which is rare)

- Infection during colonoscopy (very rare)

- Blood clots (very rare)

US Food and Drug Administration Regulations on Fecal matter transplant

In September 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that fecal microbiota met the agency’s definition of a drug/biologic substance and that, thereafter, an investigational drug application (IND) would be required to perform fecal matter transplant for any indication. This decision to apply investigational drug application (IND) requirements made fecal matter transplant largely unavailable to the community physician. Permission to perform fecal matter transplant for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection was granted in emergent cases after discussion with the FDA; however, submission of an investigational drug application (IND) was still required within 2 weeks of the procedure. In July 2013, after much dialogue and a C difficile fecal transplant public forum, the FDA decided to liberalize the restriction on fecal matter transplant while maintaining discretionary regulation.

Currently, FDA regulations permit a treating physician to perform fecal matter transplant for Clostridium difficile infection in patients who are unresponsive to standard therapy, without an investigational drug application (IND), provided that the physician obtains adequate informed consent. At a minimum, such consent should include a statement that the use of fecal matter transplant for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection is investigational and a discussion of the potential risks of fecal matter transplant. The fecal matter transplant product must be obtained from a donor known to either the patient or the treating licensed healthcare provider. Finally, the donor and the donor’s stool must be qualified by screening and testing performed under the direction of the licensed healthcare provider. The FDA still requires an investigational drug application (IND) for the use of fecal matter transplant to treat all other GI and non-GI diseases.

Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

In the only long-term follow-up study of fecal matter transplant to date, which was a combined effort from 5 medical centers, 77 patients who had had fecal matter transplant and were followed for more than 3 months experienced and maintained a 91% primary cure rate and a 98% secondary cure rate, the latter defined as cure enabled by use of antibiotics to which the patient had not responded before the fecal matter transplant or by a second fecal matter transplant 10. It is not unusual for some transient GI complaints or altered bowel habits to occur for several days after fecal matter transplant, including absence of bowel movements, abdominal cramping, gurgling bowel sounds, or increased feelings of gaseousness and bloating. Autoimmune disease (rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren syndrome, idiopathic thrombocyto-penic purpura, and peripheral neuropathy) developed in 4 of the 77 patients studied after fecal matter transplant, although a clear relationship between the onset of autoimmune disease and fecal matter transplant was not evident 10 and detailed information on these diseases is lacking.

The safety of fecal matter transplant in immunocompromised patients was reported in a retrospective, multicenter study of 61 adult and 5 pediatric immunocompromised patients treated with fecal matter transplant for refractory, recurrent, or severe Clostridium difficile infection 11. Patients were immunocompromised due to HIV infection, solid organ transplantation, oncologic conditions, immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or other immunosuppressive medications or conditions. The overall Clostridium difficile infection cure rate in this population was 89%, with an average follow-up period of 12 months. Ten (15%) patients experienced an adverse event within 12 weeks of fecal matter transplant. Eight of these patients were hospitalized for various indications. Two deaths occurred within 12 weeks of fecal matter transplant, 1 of which was the result of aspiration during sedation administered for colonoscopic fecal matter transplant, while the other was unrelated to fecal matter transplant. No patients experienced new infections or other diseases related to fecal matter transplant. Three (9%) patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) experienced a flare post-fecal matter transplant.

In another study of 12 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who were on immunosuppressive therapy (eg, infliximab [Remi-cade][Janssen], azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or oral glucocorticoids) and underwent fecal matter transplant for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), transient abdominal bloating and distention in 2 (17%) patients were the only adverse events encountered 12. Thus, few adverse events and no infectious complications were reported in all 78 patients in the 2 series described above 12. Nonetheless, safety remains the prime consideration, and larger numbers of observations in controlled circumstances are needed.

What is Clostridium difficile infection

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is a bacterium that causes inflammation of the colon, known as colitis 13. Clostridium difficile is an important cause of infectious disease death in the United States. C. difficile was estimated to cause almost half a million infections in the United States in 2011 14. Approximately 83,000 of the patients who developed C. difficile experienced at least one recurrence and 29,000 died within 30 days of the initial diagnosis 15. More than 80 percent of the deaths associated with C. difficile occurred among Americans aged 65 years or older. C. difficile causes an inflammation of the colon and deadly diarrhea.

People who have other illnesses or conditions requiring prolonged use of antibiotics and the elderly, are at greater risk of acquiring this disease. The bacteria are found in the feces. People can become infected if they touch items or surfaces that are contaminated with feces and then touch their mouth or mucous membranes. Healthcare workers can spread the bacteria to patients or contaminate surfaces through hand contact.

Figure 1. Clostridium difficile bacteria

Symptoms of Clostridium difficile infection

Symptoms include:

- Watery diarrhea (at least three bowel movements per day for two or more days)

- Fever

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Abdominal pain/tenderness

Transmission of Clostridium difficile

Clostridium difficile is shed in feces. Any surface, device, or material (e.g., toilets, bathing tubs, and electronic rectal thermometers) that becomes contaminated with feces may serve as a reservoir for the Clostridium difficile spores. Clostridium difficile spores are transferred to patients mainly via the hands of healthcare personnel who have touched a contaminated surface or item. Clostridium difficile can live for long periods on surfaces.

Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection

Whenever possible, other antibiotics should be discontinued; in a small number of patients, diarrhea may go away when other antibiotics are stopped. Treatment of primary infection caused by C. difficile is an antibiotic such as metronidazole, vancomycin, or fidaxomicin. While metronidazole is not approved for treating C. difficile infections by the FDA, it has been commonly recommended and used for mild C. difficile infections; however, it should not be used for severe C. difficile infections. Whenever possible, treatment should be given by mouth and continued for a minimum of 10 days.

One problem with antibiotics used to treat primary C. difficile infection is that the infection returns in about 20 percent of patients. In a small number of these patients, the infection returns over and over and can be quite debilitating. While a first return of a C. difficile infection is usually treated with the same antibiotic used for primary infection, all future infections should be managed with oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin.

Transplanting stool from a healthy person to the colon of a patient with repeat C. difficile infections has been shown to successfully treat C. difficile. These “fecal transplants” appear to be the most effective method for helping patients with repeat C. difficile infections. This procedure may not be widely available and its long term safety has not been established.

To date, the efficacy of fecal matter transplant for the treatment of severe and/or complicated C. difficile infections has only been reported in 1 small, multicenter study of 13 patients who had failed traditional antibiotic regimens and subsequently underwent fecal matter transplant 16. Eighty-four percent of patients had severe C. difficile infection, and 92% had complicated C. difficile infection. Patients were followed for an average of 15 months. The overall cure rate was 92%. Diarrhea and abdominal tenderness resolved rapidly an average of 4.5 and 3.3 days after fecal matter transplant, respectively. Disease-free intervals of up to 42 months were reported. Adverse effects of fecal matter transplant were minimal and included abdominal cramping and bloating.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Fecal Transplant

Fecal matter transplant for refractory ulcerative colitis has been described in 3 publications, comprising 9 patients, all of whom had severe, active, long-standing ulcerative colitis (mean, 8.6 years) refractory to treatment with glucocorticoids, 5-aminosalicylates, and azathioprine 17. Fecal matter transplant was administered as retention enemas and resulted in the complete resolution of all symptoms with cessation of ulcerative colitis medications within 6 weeks without relapse 17. Remission was maintained for up to 13 years, and follow-up colonoscopy in 8 of the 9 patients showed no evidence of ulcerative colitis (n=6) or only mild chronic inflammation (n=2) 18. In one case report on fecal matter transplant in Crohn’s disease, a patient who was refractory to prednisone and sulfasalazine responded to fecal matter transplant within 3 days, allowing discontinuation of medications 19. Disease relapsed within 18 months 17.

The use of colonoscopic fecal matter transplant followed by self-administered fecal enemas in a tapered fashion and as maintenance therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been described in an additional 16 patients, 14 with ulcerative colitis and 2 with Crohn’s disease 20. After fecal matter transplant, 14 (87.5%) of these 16 patients reported improvement in stool frequency and abdominal pain; however, the degree of benefit varied widely and was maximal in those with concomitant C. difficile infection (n=4) and in patients who were able to retain the enemas. In this series, fecal matter transplant was effective in managing refractory ulcerative colitis; however, multiple infusions on a tapering daily to weekly to monthly schedule were given to maintain remission. Additionally, fecal matter transplant provided greater therapeutic benefit in patients whose onset of ulcerative colitis was associated with an alteration in the fecal microbiota from antibiotic use or concomitant colonic infection. Experience with fecal matter transplant for ulcerative colitis is just beginning, and controlled trials are needed to establish its safety, administration regimen, and therapeutic role, if any.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Fecal Transplant

The pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is multifactorial and now believed to involve a complex interplay among the brain-gut axis, immune system, and intestinal microbiota 21.

In a series of 55 patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treated with fecal matter transplant, cure was reported in 20 (36%) patients, decreased symptoms in 9 (16%) patients, and no response in 26 (47%) patients 18. In another series, 45 patients with chronic constipation were treated with colonoscopic FMT and subsequent fecal enema infusions, 89% of whom (40 of 45 patients) reported relief in defecation, bloating, and abdominal pain immediately after the procedure 22. Normal defecation, without laxative use, persisted in 18 (60%) of 30 patients who were contacted 9 to 19 months later 22. In a recent study of 13 patients who underwent fecal matter transplant for refractory IBS (9 IBS-diarrheal, 3 IBS-constipated, 1 IBS-mixed), 70% of patients reported improvement or resolution of symptoms, including abdominal pain (72%), bowel habit (69%), dyspepsia (67%), bloating (50%), and flatus (42%) 23. Fecal matter transplant resulted in improved quality of life in 46%.

References- Glauser W. Risk and rewards of fecal transplants. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2011;183(5):541-542. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3806. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3060180/

- Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. EISEMAN B, SILEN W, BASCOM GS, KAUVAR AJ. Surgery. 1958 Nov; 44(5):854-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13592638/

- Relapsing clostridium difficile enterocolitis cured by rectal infusion of homologous faeces. Schwan A, Sjölin S, Trottestam U, Aronsson B. Lancet. 1983 Oct 8; 2(8354):845. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6137662/

- Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Bakken JS, Borody T, Brandt LJ, Brill JV, Demarco DC, Franzos MA, Kelly C, Khoruts A, Louie T, Martinelli LP, Moore TA, Russell G, Surawicz C, Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Workgroup. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Dec; 9(12):1044-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3223289/

- Aas J, Gessert CE, Bakken JS. Recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: case series involving 18 patients treated with donor stool administered via a nasogastric tube. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(5):580–585. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12594638

- Persky SE, Brandt LJ. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea by administration of donated stool directly through a colonoscope. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(11):3283–3285. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11095355

- Silverman MS, Davis I, Pillai DR. Success of self-administered home fecal transplantation for chronic Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(5):471–473. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20117243

- Brandt LJ, Reddy SS. Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(suppl):S159–S167. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21992957

- Gough E, Shaikh H, Manges AR. Systematic review of intestinal microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(10):994–1002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22002980

- Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Mellow M, et al. Long-term follow-up of colono-scopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):1079–1087. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22450732

- Ihunnah C, Kelly C, Hohmann E, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):S179.

- Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC, Greenberg A, et al. Safety of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in immunocompromised (Ic) patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(suppl 1) A1840.

- Clostridium difficile. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/cdiff-patient.html

- Clostridium difficile. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/cdiff_clinicians.html

- Burden of Clostridium difficile Infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:825-834February 26, 2015DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913 http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1408913

- Long-term Follow-up Study of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Severe and/or Complicated Clostridium difficile Infection: A Multicenter Experience. Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ, Greenberg A, Borody T, Kelly CR, Mellow M, Surawicz C, Cagle L, Neshatian L, Stollman N, Giovanelli A, Ray A, Smith R. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 May-Jun; 50(5):398-402. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26125460/

- Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis SM, Surace R, Ashman O, Siarakas S. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004 Jul; 38(6):475-83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15220681/

- Bowel-flora alteration: a potential cure for inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome? Borody TJ, George L, Andrews P, Brandl S, Noonan S, Cole P, Hyland L, Morgan A, Maysey J, Moore-Jones D. Med J Aust. 1989 May 15; 150(10):604. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2783214/

- Borody TJ, Leis S, McGrath K, et al. Treatment of chronic constipation and colitis using human probiotic infusions. Presented at: Probiotics, Prebiotics and New Foods Conference; Rome, Italy; September 2-4, 2001.

- Greenberg A, Aroniadis O, Shelton C, Brandt LJ. Long-term follow-up study of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(suppl 1) A1791.

- Intestinal microbiota and immune function in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome. Ringel Y, Maharshak N. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013 Oct 15; 305(8):G529-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3798736/

- Andrews P, Borody TJ, Shortis NP, Thompson S. Bacteriotherapy for chronic constipation—long term follow-up. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(4) A563.

- Pinn DM, Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ. Follow-up study of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for the treatment of refractory irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Presented at: American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting; San Diego, CA; October 11-16, 2013.