Ghon complex

Ghon complex represents a tuberculous caseating granuloma (tuberculoma) with ipsilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Specifically, in parenchymal pulmonary tuberculosis infection, primary tuberculosis is hallmarked with a pulmonary lesion also known as a Ghon lesion or Ghon focus and affected draining lymph node adenopathy forming the Ghon’s complex (see Figure 1) 1. Radiologically, Ghon complex is used quite loosely to refer to a calcified granuloma; technically, the Ghon lesion is the initial tuberculous granuloma formed during primary infection and is not radiologically visible unless it calcifies, this occurs in up to 15% of cases, where it become known as a Ghon focus 2. A calcified Ghon complex (Ghon lesion and ipsilateral mediastinal lymph node) is called a Ranke complex, which is radiologically detectable. Thus the Ranke complex represents a progression of the Ghon complex, rather than being a separate entity in itself 2.

The first report of the Ghon complex was by Anton Ghon (1866-1936), an Austrian pathologist who described primary tuberculosis to have the findings of a pulmonary lesion with regional lymph involvement caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis 3. Primary pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) infection on chest radiography commonly presents with either one of the following four presentations: parenchymal disease, lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions, miliary tuberculosis, and the possibility of any combination of these.

The Ghon complex is a non-pathognomonic radiographic finding on a chest x-ray that is significant for pulmonary infection of tuberculosis 4. The major route of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is by inhalation 5. Infection begins when infected droplets are deposited in the terminal airway or alveoli, followed by a localized parenchymal inflammation or pneumonic process called the primary Ghon focus 1. The location of the Ghon’s focus is usually subpleural and predominantly in the upper part of the lower lobe and lower part of the middle or upper lobe. The predilection for this area is because the ventilation is best in this region, and the most frequently encountered route of infection is through the respiratory tract 4. Radiographic findings of the Ghon focus may include parenchymal scarring of the lung tissue, lesion cavitation, or lobar consolidation, as seen in Figure 2.

There is then spread via draining lymphatic vessels, usually to the ipsilateral central or regional lymph nodes, which then enlarge. The upper lobes drain to the ipsilateral paratracheal nodes, while the rest of the lung drains to the perihilar nodes. Regional (perihilar or paratracheal) lymphadenopathy is the radiologic hallmark of primary tuberculosis infection in childhood (Figure 3) 5. Anteroposterior and lateral views are required for optimal lymph node visualization 6, but it can remain difficult to visualize enlarged lymph nodes with certainty 7. The most common sites of nodal involvement are the right paratracheal and hilar regions 8.

The Ghon focus (parenchymal focus) and the enlarged lymph nodes are called the primary Ghon complex. The Ghon complex should not be confused with the Ranke complex. The Ghon complex precedes the development of a Ranke complex, in that a Ghon complex is seen in untreated primary pulmonary tuberculosis infection with Ghon lesion fibrosis while the Ranke complex is a result of the healing of a primary tuberculosis. Ghon complex characterized by a calcified Ghon lesion and calcified mediastinal lymph nodes 9.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis incubation can be up to 6 weeks from exposure, during which time chest radiographs are normal. After 1–3 months from exposure, hilar or mediastinal adenopathy can be visualized in 50–70% of cases 10. Primary tuberculosis reflects a patient’s conversion from insensitivity to having the antigens of the tubercle bacilli 11.

The diagnosis of primary tuberculosis heavily relies on confirmatory specimen culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis from either sputum, nasopharyngeal aspirate, gastric aspirate, or pleural fluid. Nucleic acid amplification tests (such as the Xpert MTB or RIF assay), serological test, and chest radiography support the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis 12. The Ghon complex is not always present in a patient with primary tuberculosis infections. Researchers estimate that in about 15% of cases of primary tuberculosis, a Ghon focus may develop, while 9% of cases of primary tuberculosis may develop tuberculomas and lymphadenopathy presents in children and adults only 96% and 43% of cases respectively 13.

An estimated two-thirds of cases of primary tuberculosis, a parenchymal focus, resolves on its own, and overall, about 15% of patients with primary tuberculosis may present with normal chest radiography 13. Due to the nature of Mycobacterium tuberculosis’s ability to spread from the respiratory tract to distant parts of the body by lymphatic and hematogenous routes, untreated primary pulmonary tuberculosis can result in latent disease and extrapulmonary tuberculosis of the pericardium and myocardium, central nervous system, head, and neck, musculoskeletal variants of arthritis, spondylitis, and osteomyelitis, either abdominal organs or gastrointestinal tract, and the genitourinary tract. Pulmonary tuberculosis is a curable disease that requires extended use of antibiotics. It appears in the literature that there is multiple drug-resistant or extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, which requires clinicians to monitor a patient’s response to tuberculosis treatment carefully 14.

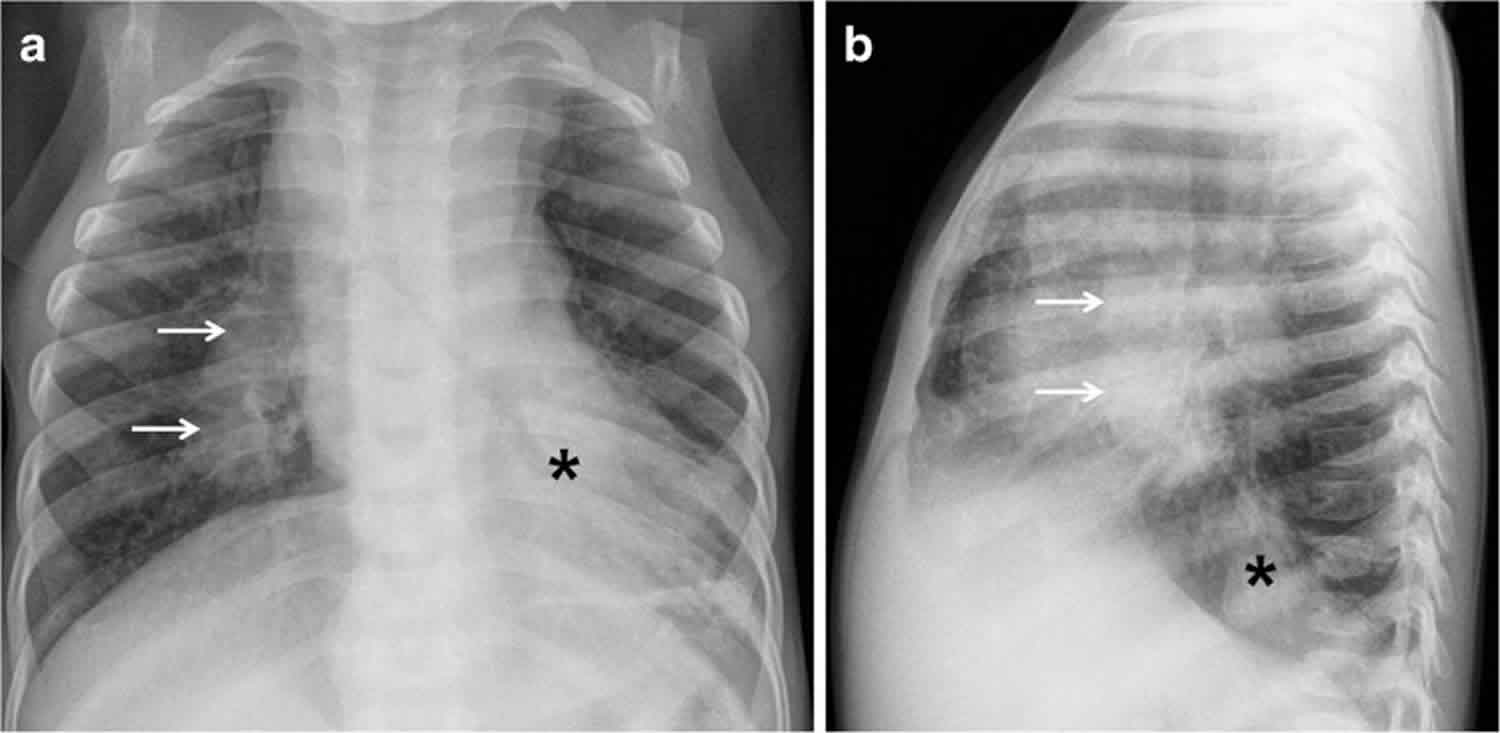

Figure 1. Ghon complex

Footnote: Diagram of a Ghon focus (yellow) and associated lymphadenopathy (green).

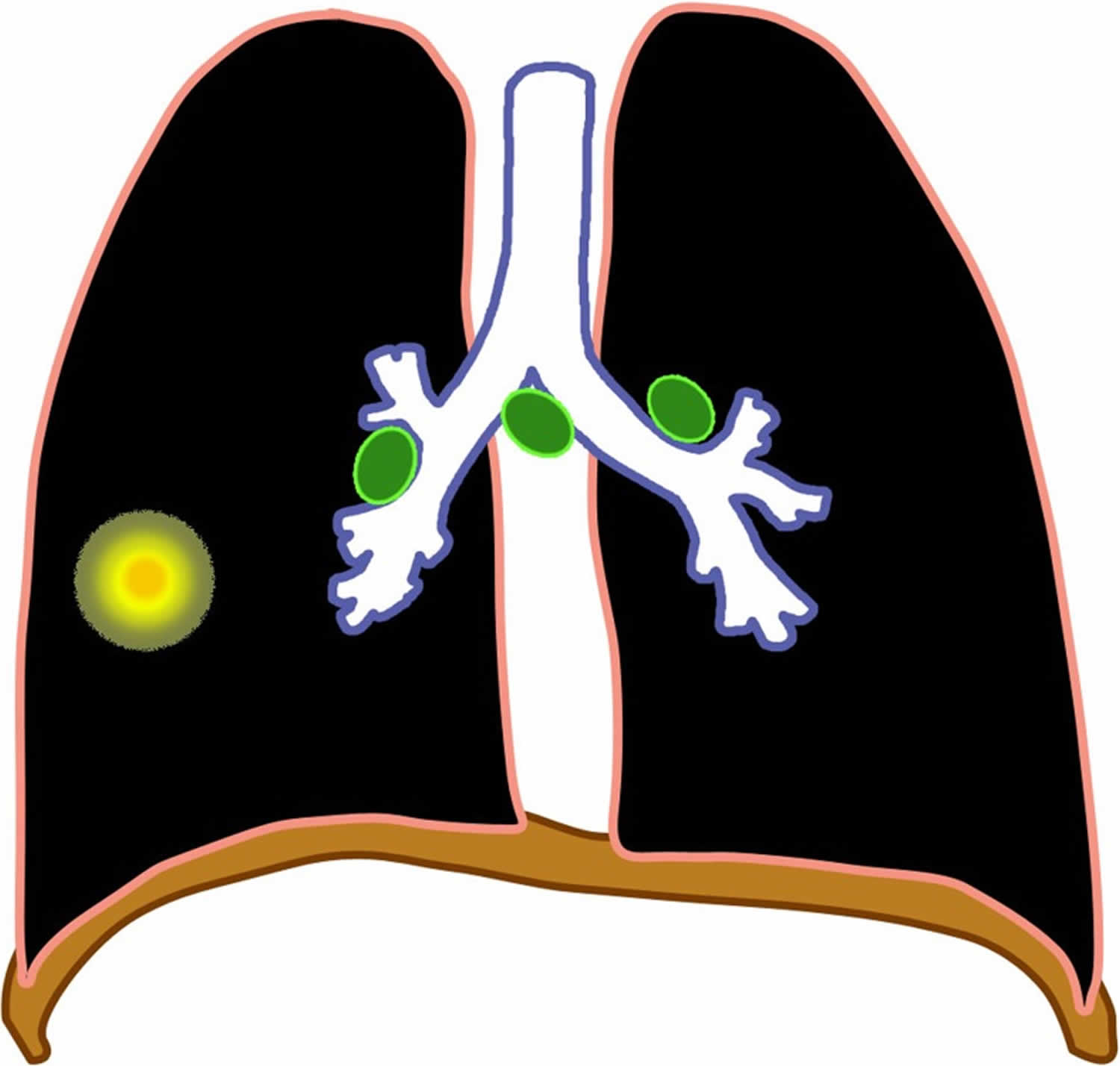

[Source 1 ]Figure 2. Ghon focus

Footnote: An anteroposterior X-ray of a patient diagnosed with advanced bilateral pulmonary tuberculosis. This anteroposterior (AP) X-ray of the chest reveals the presence of bilateral pulmonary infiltrate (white triangles), and “caving formation“ (black arrows) present in the right apical region. The diagnosis is advanced tuberculosis.

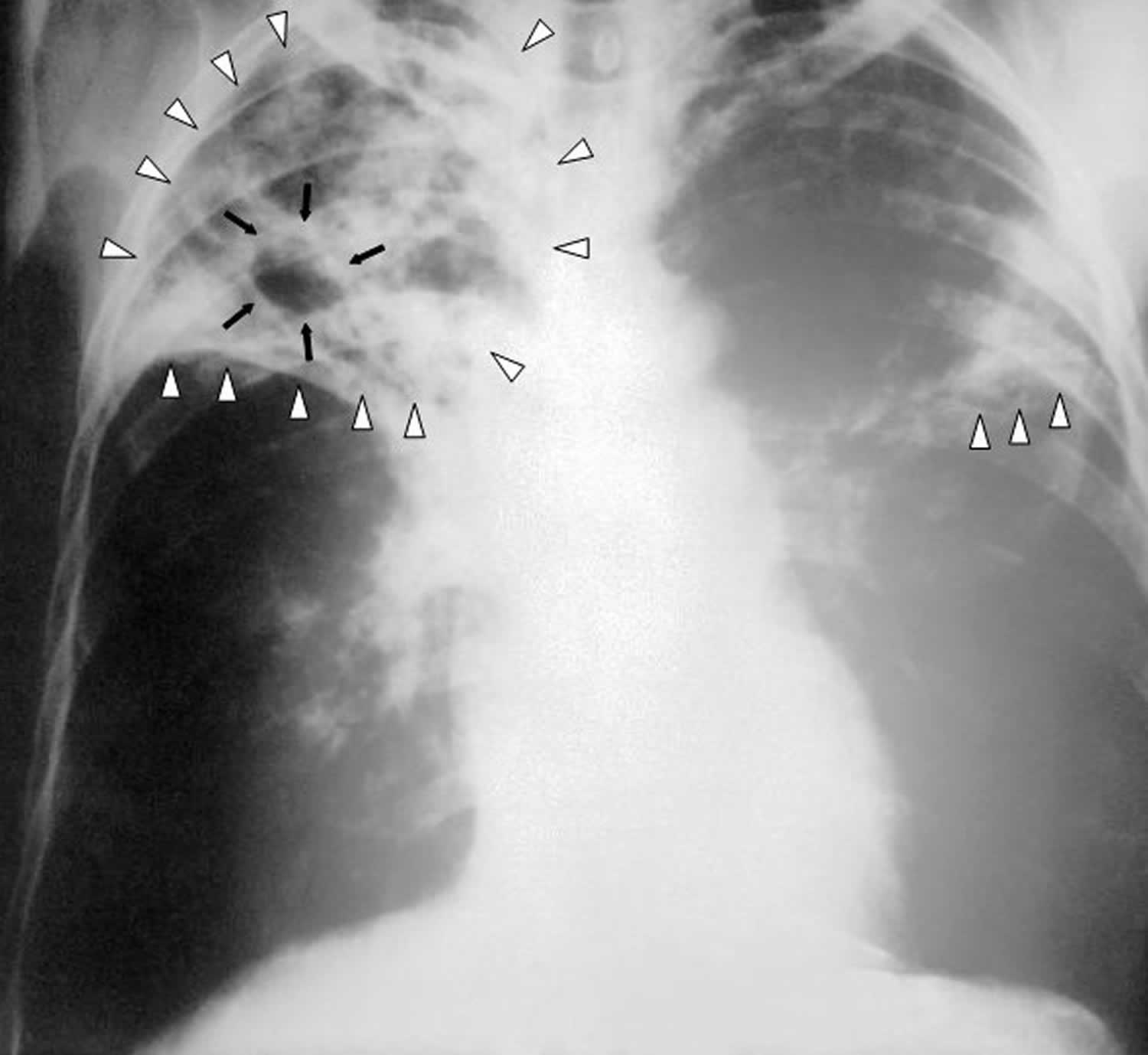

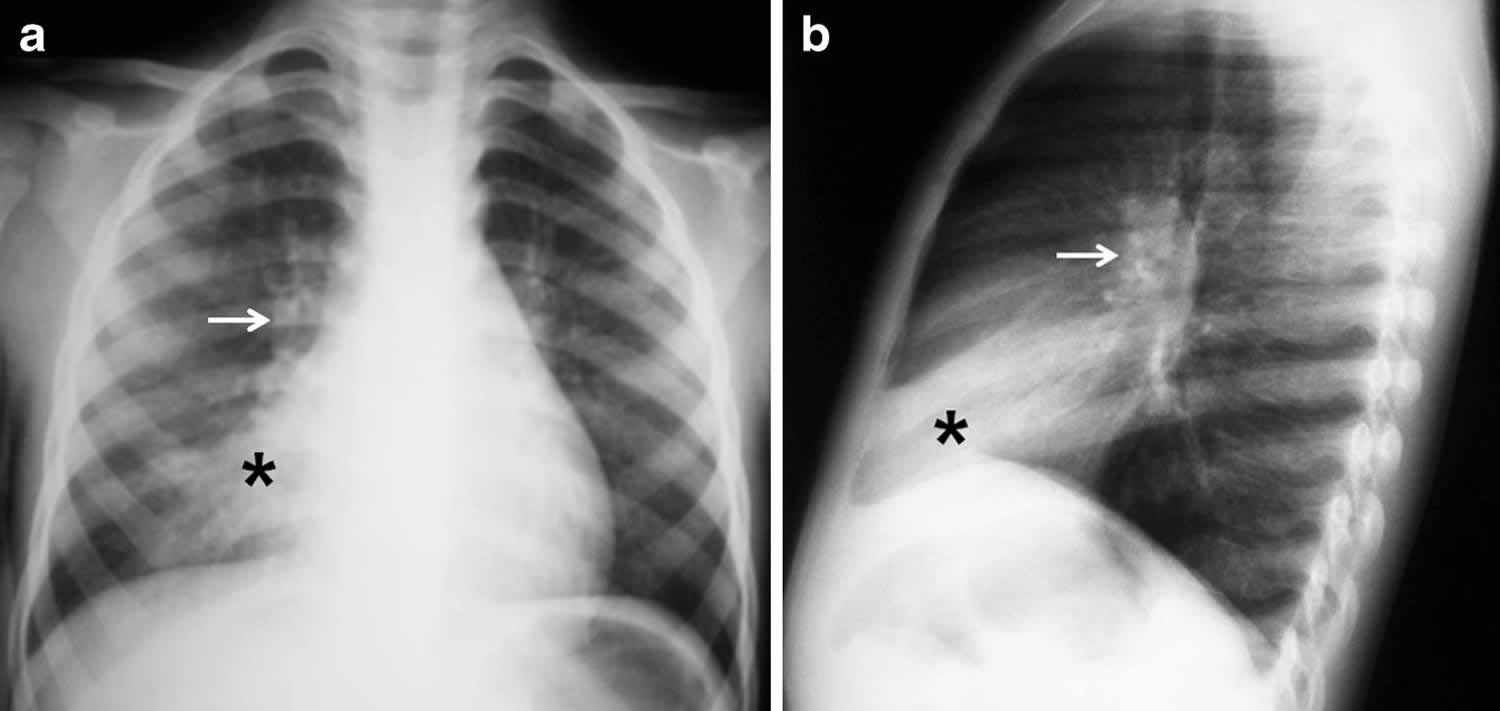

Figure 3. Primary tuberculous disease

Footnote: Chest radiographs in a 5-year-old girl with primary tuberculous disease. (a, b) Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) views show a middle lobe opacity (asterisk) with right hilar lymphadenopathy (arrow).

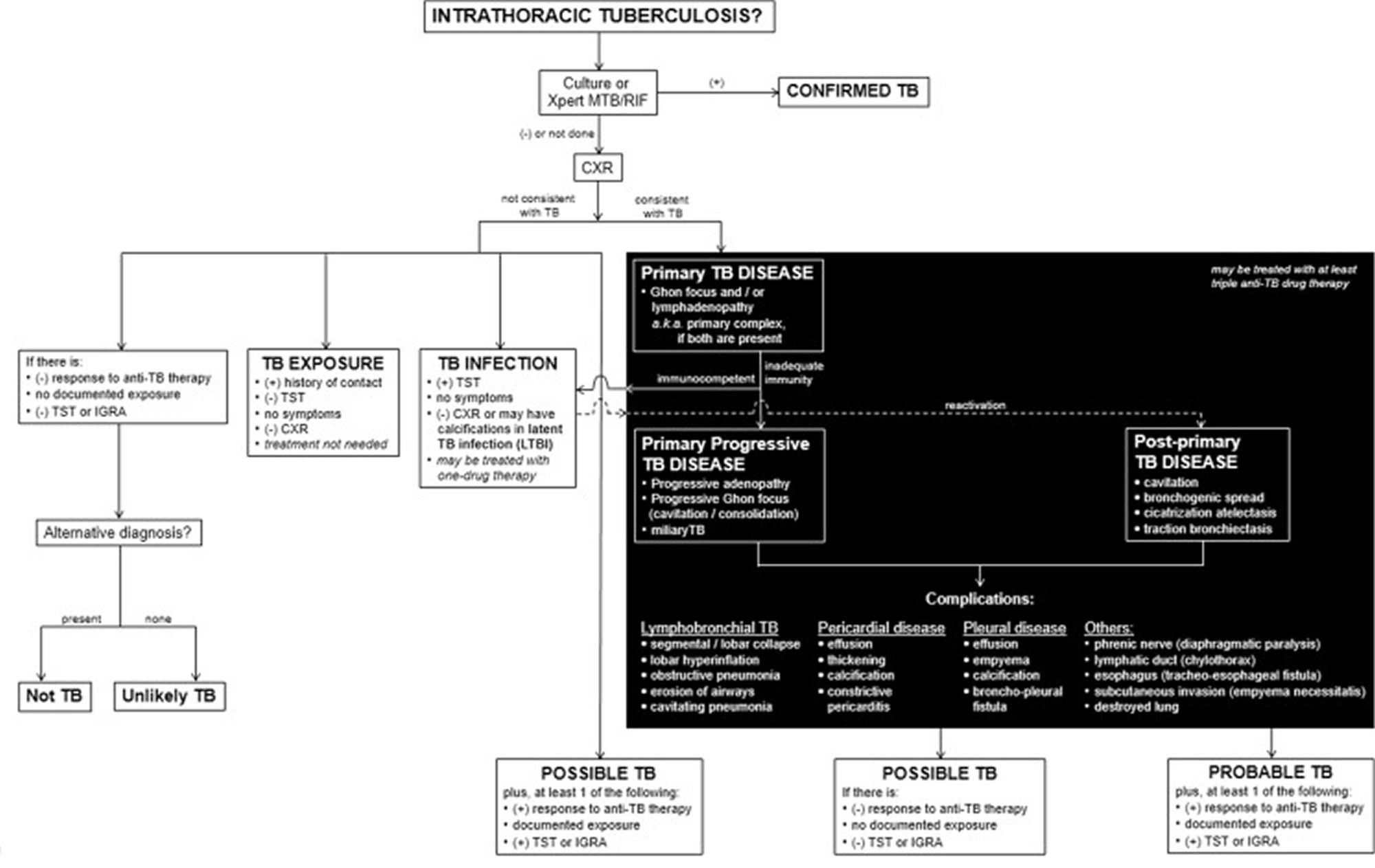

[Source 1 ]Figure 4. Classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis

Foothote: This is the proposed approach to classify intrathoracic tuberculosis (TB) in children. It includes clinical, laboratory and radiologic (in black background) components. The imaging characteristics follow the pathological processes and the possible complications that occur. The impression of the imaging findings should contain the main pathology (i.e. primary tuberculosis infection, primary progressive tuberculous disease or post-primary tuberculous disease) followed by the various complications present (e.g., primary progressive tuberculosis with lymphobronchial involvement and pleural disease).

Abbreviations: CXR = chest radiograph; IGRA = interferon-gamma release assay; LTBI = latent tuberculous infection; TB = tuberculosis; TST= tuberculin skin test; Xpert MTB/RIF test to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis and resistance to rifampicin 15

[Source 1 ] References- Concepcion NDP, Laya BF, Andronikou S, et al. Standardized radiographic interpretation of thoracic tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47(10):1237-1248. doi:10.1007/s00247-017-3868-z https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5574960

- Burrill J, Williams CJ, Bain G, Conder G, Hine AL, Misra RR. Tuberculosis: a radiologic review. Radiographics. 2007 Sep-Oct;27(5):1255-73. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.275065176

- Delgado BJ, Bajaj T. Ghon Complex. [Updated 2020 Sep 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551706

- Delgado BJ, Bajaj T. Ghon Complex. [Updated 2020 Sep 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551706

- Marais BJ, Gie RP, Simon Schaaf H, et al. A proposed radiological classification of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:886–894. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1238-0

- Leung AN, Muller NL, Pineda PR, et al. Primary tuberculosis in childhood: radiographic manifestations. Radiology. 1992;182:87–91. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727316

- Andronikou S, Joseph E, Lucas S, et al. CT scanning for the detection of tuberculous mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:232–236. doi: 10.1007/s00247-003-1117-0

- Kim WS, Choi J, II, Kim I-O, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in infants: radiographic and CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1024–1033. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.0751

- Skoura E, Zumla A, Bomanji J. Imaging in tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2015 Mar;32:87-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.007

- Perez-Velez CM, Marais BJ. Tuberculosis in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:348–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1008049

- Van Dyck J, Vanhoenacker FM, Van den Brande P, et al. Imaging of pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1771–1785. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1612-y

- Schito M, Migliori GB, Fletcher HA, McNerney R, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, Bates M, Kibiki G, Kapata N, Corrah T, Bomanji J, Vilaplana C, Johnson D, Mwaba P, Maeurer M, Zumla A. Perspectives on Advances in Tuberculosis Diagnostics, Drugs, and Vaccines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015 Oct 15;61Suppl 3:S102-18.

- Burrill J, Williams CJ, Bain G, Conder G, Hine AL, Misra RR. Tuberculosis: a radiologic review. Radiographics. 2007 Sep-Oct;27(5):1255-73. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065176 https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.275065176

- Caminero JA, Cayla JA, García-García JM, García-Pérez FJ, Palacios JJ, Ruiz-Manzano J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017 Sep;53(9):501-509.

- World Health Organization (2013) Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB in adults and children: policy update. World Health Organization, Geneva