Gingival cyst of newborn

Gingival cyst of newborn is an oral mucosal lesion of transient nature. Although it is very common lesion within 3 to 6 weeks of birth, it is very rare to visualize the lesion thereafter. Gingival cysts of the newborn also called Bohn’s nodules, can manifest as few or many, white to yellowish, round to oval, nodes in the maxillary and/or mandibular gingiva and alveolar ridge of newborns 1. These nodes generally measure 2 to 3 millimeters in their largest dimension. Bohn’s nodules are keratin cysts derived from remnants of odontogenic epithelium over the dental lamina or may be remnants of minor salivary glands. They occur on the alveolar ridge, more commonly on the maxillary than mandibular. Bohn’s nodules usually rupture spontaneously and disappear within a few weeks to a few months. Counseling of the family members regarding its benign and self-limiting nature is all that is required in the management.

Fromm 2 classified conditions affecting newborns as Epstein’s pearls, Bohn’s nodules and dental lamina cysts. Based on histological origin and location in the oral cavity, these can be classified as Epstein’s pearls, Bohn’s nodules, and gingival cysts. Gingival cysts of newborns generally occur in multiples but occasionally occur as solitary nodule also. They are located on the alveolar ridges of newborns or young infants. It is believed that fragments of dental lamina that remains within the alveolar ridge mucosa after tooth formation proliferate to form these small keratinized cysts. They are generally asymptomatic and do not produce any discomfort for the infant 3..

Based on the location, gingival cysts of the newborn may be divided into palatal and alveolar cysts. Those located at the mid-palatine raphe are referred as palatine cysts while those present on the buccal, lingual or crest of alveolar ridge as alveolar (or gingival) cysts 4. The reported prevalence of alveolar cysts in newborn ranges from 25 to 53% 5, while for palatal cysts is about 65% 6. Individually, the prevalence of gingival cyst of infants is 13.8%, Epstein’s pearl is 35.2% and Bohn’s nodules is 47.4% 7 with no sexual predilection. Although prevalence is high, these cysts are rarely seen by the dentist or pediatrician because of transient nature of these cysts, which disappears within 2 weeks to 5 months of postnatal life.

Dental lamina cyst (gingival cyst of newborn) are remnants of dental lamina epithelium found on the crest of the alveolar mucosa. Dental lamina cyst is a benign oral mucosal lesion of transient nature. Dental lamina cysts (gingival cysts) are yellow-white cystic lesion over the alveolar crest that arises from epithelial remnants of the degenerating dental lamina. Dental lamina cysts (gingival cysts) may be greater in size, more transparent, solitary lesion and fluctuant. Dental lamina cysts (gingival cysts) are usually multiple but do not increase in size. Since the lesions are self-limiting and spontaneously shed a few weeks or months after birth no treatment is required. Clinical diagnoses of these conditions are important in order to avoid unnecessary therapeutic procedure and provide suitable information to parents about the nature of the lesion. In addition, it may be incorrectly diagnosed as natal teeth if present in mandibular anterior region.

Epstein pearls are small, firm, white, keratin-filled cysts located on the mid-palatal raphe at the junction of the hard and soft palates 8. Some authors use the terms Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and dental lamina cysts interchangeably. However, Epstein pearls have been labeled as epithelial debris of the tooth follicle, gingival glands of Serres, and as abortive enamel organs on the Palatine area. On the other hand, Bohn’s nodules are those found along the buccal and lingual aspects of the dental ridges.

Epstein pearls are observed in nearly 60% to 85% of newborn infants. Among the different racial groups, Japanese newborns are most commonly affected (up to 92%), followed by Caucasians and African-Americans 8. No gender predilection has been observed through the years 8.

In one study, Epstein pearls were more common in infants born to multigravida mothers, also with those with higher birth weight. One study done in Turkey found that Epstein’s pearls were less frequent in post-term babies in comparison with pre-term and term ones. A greater rate seen in term babies was reported. 8.

Epstein pearls are a clinical diagnosis. No laboratory or imagining is needed.

Epstein pearls are small, opaque whitish-yellow lesions adjacent to the mid palatine raphe with no mucous glands in it. Epstein pearls are firm in consistency, size range from less than a millimeter to several millimeters in diameter. Size does not progress over time. Epstein pearls can be palpated during sucking by the examiner.

- Epstein pearls can be seen in cluster groups of 2 to 6 cysts, although they can present as an isolated lesion. Their distribution varied from mouth to mouth, barely being identical even in twins.

- Occasionally these cysts show communication with the mucosal surface.

- Cleft children appear to have cysts in the identical distribution pattern as non-cleft children except for those with a cleft palate which are located at the margins of the palatal shelves instead of the midline.

- Parents of newborn infants sometimes worriedly visit a dental surgeon or pediatrician, complaining of the presence of these abnormal structures in the mouth of their infants.

- The clinician should explain that Epstein pearls are benign and asymptomatic, with no interference with feedings or tooth eruption.

- Epstein pearls resemble the equivalent of milia (white papules produced by retention of sebum and keratin in the hair follicles), which are frequently seen on the faces of neonates.

The cyst is lined by odontogenic epithelium which is covered by a thick layer of keratin, which gives the cyst its yellow color 1. As it is lined by thin epithelium and shows a lumen usually filled with desquamated keratin, occasionally containing inflammatory cells 3. These structures originate from remnants of the dental lamina and are located in the corium below the surface epithelium. The nodes are result of cystic degeneration of epithelial rests of the dental lamina (rests of Serres). After the dental lamina invaginates to form the dental organ, the epithelial pedicle that connects the dental organ to the surface epithelium is broken down giving rise to the rests of Serres. Occasionally, they may become large enough to be clinically noticeable as discrete white swellings on the ridges. Majority of these cysts degenerate and involutes or rupture into the oral cavity within 2 weeks to 5 months of postnatal life 9. The diagnosis of gingival cyst must be differentiated from three other conditions, which are typically seen during the same time and possibly also have a location similarity. These include Natal teeth, Epstein’s pearls and Bohn’s nodules. Palatally located cysts in newborns were first described by Alois Epstein and are often referred to as Epstein’s pearls. These are also keratinized cysts which occur along the median palatal raphae and arise from the epithelium entrapped along the line of fusion. Bohn’s nodules, so called after his description of the same in 1866, are scattered over the junction of the hard and soft palate and are derived from minor salivary glands. Bohn also classified cysts in the alveolar ridges as mucous gland cysts. However, later studies by Moreillon and Schroeder 10 have shown that these cysts are microkeratocysts.

The majority of these cysts break by themselves, a few days after birth, exuding the keratin. In some cases however, they may remain for a period of several months and in such cases surgical opening is indicated.

Figure 1. Gingival cysts of the newborn (Bohn’s nodules)

Footnote: A full term newborn boy, weighing 3 kg, born out of an uncomplicated pregnancy, was brought to us for evaluation of a few small, white and round bumps on the gingival surface. Examination of the oral cavity showed multiple, firm, pearly-white papules measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, grouped over the vestibular aspect of the alveolar ridge of the maxillary arch (Figure 1). Two similar lesions were seen on the mandibular area. These lesions were asymptomatic, non-tender, and fixed to the mucosa. Oral mucosa was otherwise normal. A few milia were noted on his chin. Detailed systemic examination was normal. No specific therapy was prescribed. Within a couple of months, most of the lesions subsided spontaneously. Based on the clinical features and the natural course of the disease, a diagnosis of Bohn’s nodule was made.

Figure 2. Dental lamina cyst (gingival cyst)

Footnote: A 14-day-old male newborn infant presented with nodular papules in the deciduous lower central incisor region. No treatment of any kind was

done, except for parental counseling and reassurance. It is important to note that management of all oral inclusion cysts (dental lamina cysts, Epstein pearls and Bohn’s nodules) remains the same, as all these have a self-limiting nature and require no treatment.

Figure 3. Epstein pearls on hard palate

Figure 4. Natal tooth

[Source 12 ]Gingival cysts of newborn treatment

No treatment or removal is required 8. Most of these cysts involute or spontaneously rupture eliminating their keratin contents into the oral cavity within the first few weeks to months of postnatal life. The mechanisms behind the disappearance of the cysts in postnatal life have been attributed to a discharge of cystic keratin at the time of fusion of the cyst walls with the oral epithelium. However, it has been suggested that part of the cystic epithelium may remain inactive even in the adult gingiva. The majority of these cysts break by themselves, a few days after birth, exuding the keratin. In some cases however, they may remain for a period of several months and in such cases surgical opening is indicated.

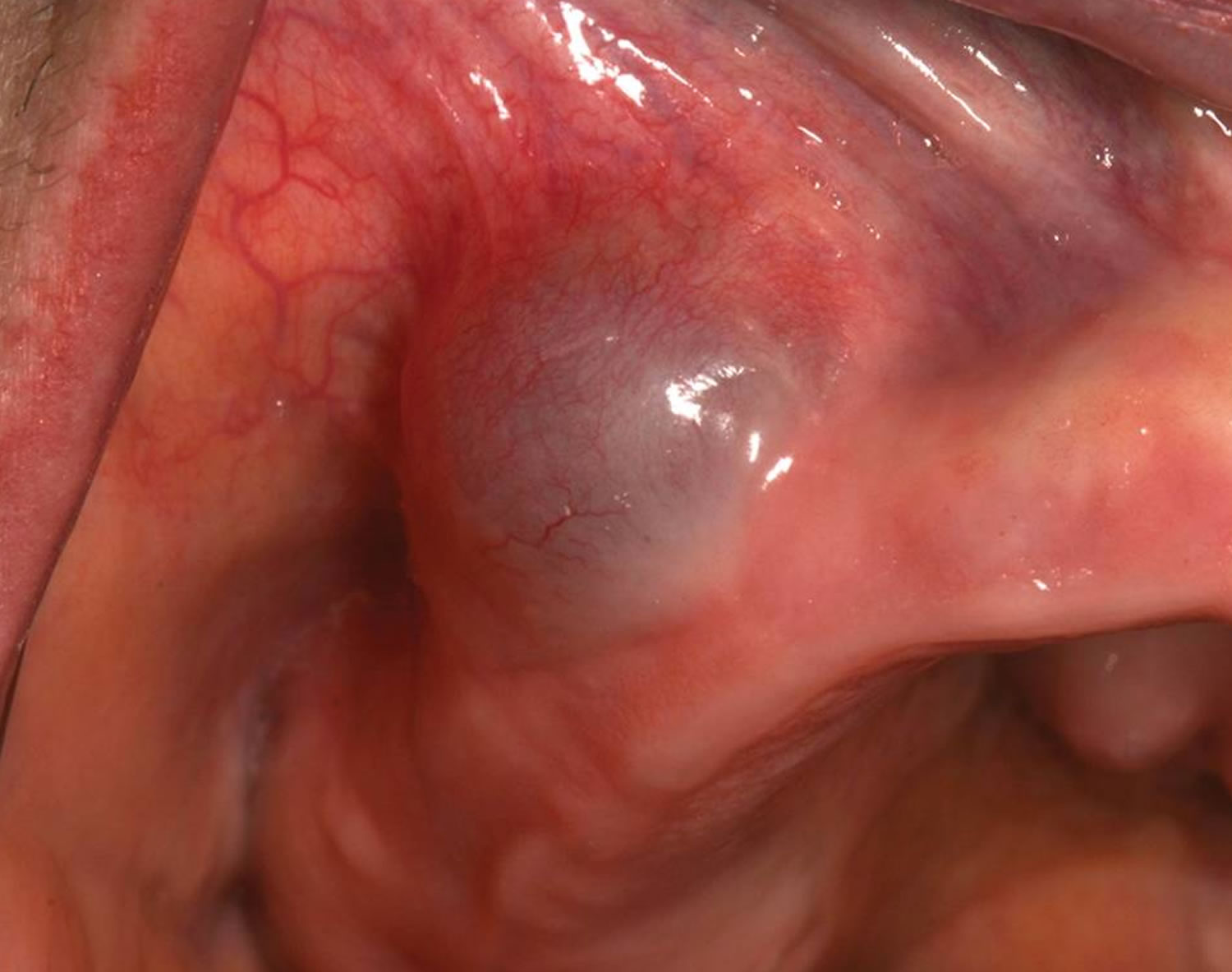

Gingival cyst of adults

Gingival cyst of adult is a rare developmental anomaly of odontogenic origin elieved to arise from rests of the dental lamina (rests of Serres) in the gingival soft tissues 13. Gingival cyst of adult is asymptomatic, slow growing, and commonly seen near the canine and premolar region of mandible, which accounts for nearly 75% of cases 14. Maxillary examples also are found most frequently in the canine/premolar region, as well as the lateral incisor area (Figure 5). The gingival cyst of the adult usually occurs in middle-aged and older patients, most often in the fifth and sixth decades of life. The reason why such developmental cysts should occur in this location at this age of life is unexplained 13.

Microscopically, the diagnosis of the gingival cyst of the adult is usually straightforward. The cystic cavity is lined by a thin layer of flattened epithelial cells ranging from one to three cells in thickness. In many cases, this lining will demonstrate occasional plaque-like or nodular thickenings that often include cells with a clear cytoplasm. The cells in these thickened areas sometimes demonstrate a swirling appearance. The clear cells often contain glycogen, as demonstrated by periodic acid-Schiff staining, with and without prior diastase digestion.

Normally, patients with a gingival cyst of the adult have a history of a slow growing painless swelling 15. The lesion is often less than 6 mm in diameter and may present the same color as the adjacent normal mucosa or even a bluish hue due to the cystic fluid 16.

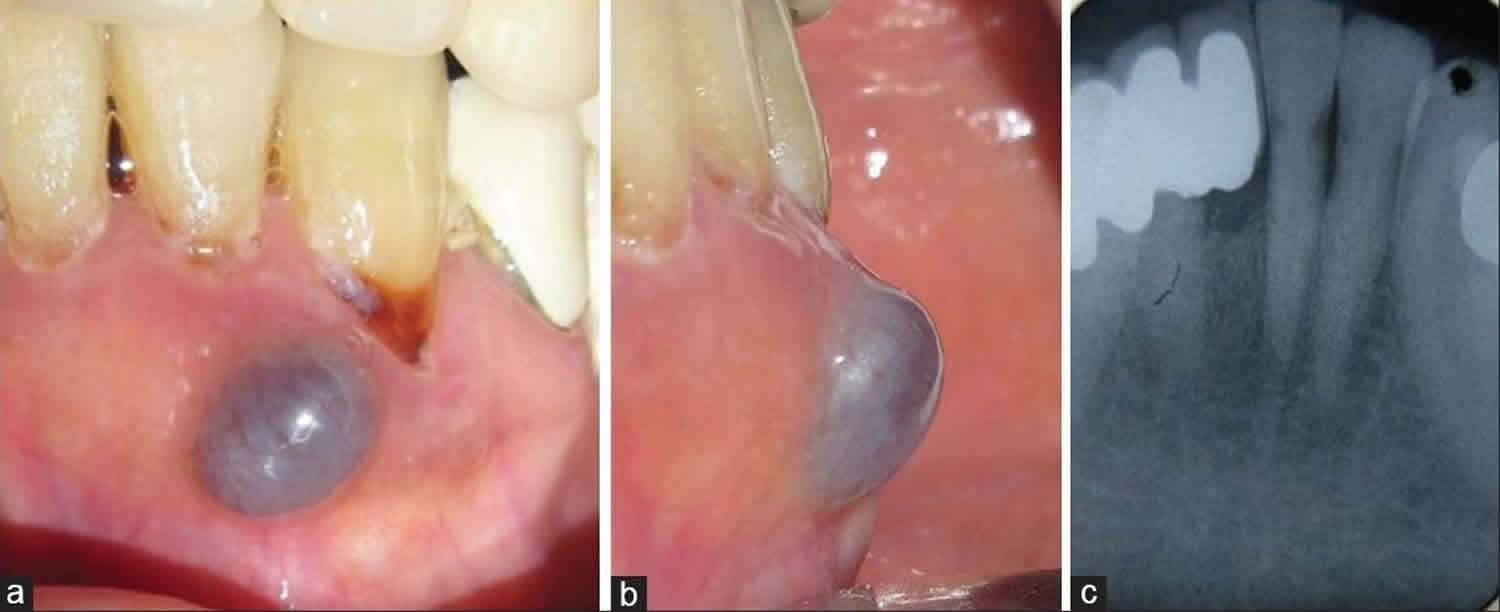

Figure 5. Gingival cyst of adults

Footnote: A blue, fluctuant swelling of the right maxillary buccal alveolar mucosa [Source 13 ]

Figure 6. Gingival cyst of the adult

Footnote: Preoperative presentation of the lesion. (a) Labial view; (b) Mesial view; (c) Intraoral periapical with respect to 31, 32, and 33 showing no radiographic involvement.

[Source 14 ]Gingival cyst of adults treatment

Treatment of gingival cysts of the adult is primarily surgical excision, which carries a good prognosis, as no case has yet been reported of postoperative relapse 17. In the case presented herein, a follow-up of 15 months has been associated with no recurrence, as suggested by the literature reviewed.

References- Moda A. Gingival Cyst of Newborn. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011;4(1):83–84. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1087 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4999644

- Fromm A. Epstein pearls, Bohn’s nodules and inclusion-cysts of the oral cavity. J Dent Child. 1967 Jul;34(4):275–287.

- Morelli JG. Disorders of the mucous membranes. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. p. Chapter 663

- Paula JD, Dezan CC, Frossard WT, Walter LR, Pinto LM. Oral and facial inclusion cysts in newborns. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;31(2):127–129.

- Friend GW, Harris EF, Mincer HH, Fong TL, Carruth KR. Oral anomalies in neonate, by race and gender, in urban setting. Pediatr Dent. 1990 May-Jun;12(3):157–161.

- Cataldo E, Berkman MD. Cysts of the oral mucosa in newborns. Am J Dis Child. 1968 Jul;116(1):44–48.

- George D, Bhat SS, Hegde SK. Oral findings in newborn children in and around Mangalore, Karnataka State, India. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(5):385–389

- Diaz de Ortiz LE, Mendez MD. Epstein Pearls. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493177

- Regezi JA. Cyst of jaws and neck. In: Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jorden RC, editors. Oral pathology: Clinical pathological correlation. 4th edition. WB Saunders Co; 1999. p. 246.

- Moreillon MC, Schroeder HE. Numerical frequency of epithelial abnormalities, particularly microkeratocysts, in the developing human oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982 Jan;53(1):44–55.

- Singh RK, Kumar R, Pandey RK, Singh K. Dental lamina cysts in a newborn infant. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012007061. Published 2012 Oct 9. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007061 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4544414/

- Clark MB, Clark DA. Oral Development and Pathology. Ochsner J. 2018;18(4):339-344. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6292461/

- Neville BW. Update on current trends in oral and maxillofacial pathology. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1(1):75–80. doi:10.1007/s12105-007-0007-4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2807501

- Karmakar S, Nayak SU, Kamath DG. Recurrent Gingival Cyst of Adult: A Rare Case Report with Review of Literature. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2018;22(6):546–550. doi:10.4103/jisp.jisp_382_18 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6305099

- Shear M., Speight P. Cysts of the Oral and Maxillofacial Regions. 4th. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2007

- Sato H., Kobayashi W., Sakaki H., Kimura H. Huge gingival cyst of the adult: a case report and review of the literature. Asian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2007;19(3):176–178. doi: 10.1016/s0915-6992(07)80020-3

- Brod JM, Passador-Santos F, Soares AB, Sperandio M. Gingival Cyst of the Adult: Report of an Inconspicuous Lesion Associated with Multiple Agenesis. Case Rep Dent. 2017;2017:4346130. doi:10.1155/2017/4346130 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5362702