Gitelman syndrome

Gitelman syndrome also called familial hypokalemia-hypomagnesemia or tubular hypomagnesemia-hypokalemia with hypocalcuria, is a kidney function disorder that causes an imbalance of charged atoms (ions) in the body, including ions of potassium, magnesium, and calcium 1. Gitelman syndrome is a rare, salt-losing tubulopathy characterized by hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria 2. Gitelman syndrome signs and symptoms usually appear in late childhood or adolescence 3.

Common symptoms of Gitelman syndrome include excessive tiredness (fatigue), salt craving, thirst, frequent urination, muscle cramping, painful muscle spasms (tetany), muscle weakness, dizziness, tingling or numbness sensation in the skin (paresthesias) most often affecting the face, low blood pressure, heart palpitations and a painful joint condition called chondrocalcinosis 2. Studies suggest that Gitelman syndrome may also increase the risk of a potentially dangerous abnormal heart rhythm called ventricular arrhythmia. The signs and symptoms of Gitelman syndrome vary widely, even among affected members of the same family. Most people with this condition have relatively mild symptoms, although affected individuals with severe muscle cramping, paralysis, and slow growth have been reported.

Gitelman syndrome affects an estimated 1 in 40,000 people worldwide 1.

Gitelman syndrome can be caused by changes (mutations) in the SLC12A3 or CLCNKB genes and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner 4. Treatment may include supplementation of potassium and magnesium, and a high sodium and high potassium diet 3.

The mainstay treatment of Gitelman syndrome involves careful monitoring, high-sodium and potassium diet, and oral potassium and magnesium supplements. Intravenous magnesium and/or potassium may be needed if symptoms are severe. People who have low potassium levels despite supplementation and diet, may benefit from potassium-sparing diuretics, renin angiotensin system blockers, pain medications, and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

The Blanchard A et al., 2017 consensus guideline 2 offers detailed treatment information, including information on drug selection, dosing recommendations, and a listing of drugs that can cause adverse effects in people with Gitelman syndrome.

Lastly, people with Gitelman syndrome should have a thorough heart work-up. People with Gitelman syndrome and a prolonged QT interval should avoid drugs that prolong the QT interval. The Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndromes Foundation (https://www.sads.org/living-with-sads/Drugs-to-Avoid) offers a tool for learning more about what drugs to avoid.

Gitelman syndrome causes

Gitelman syndrome is usually caused by mutations in the SLC12A3 gene. Less often, the condition results from mutations in the CLCNKB gene. The proteins produced from these genes are involved in the kidneys’ reabsorption of salt (sodium chloride or NaCl) from urine back into the bloodstream. Mutations in either gene impair the kidneys’ ability to reabsorb salt, leading to the loss of excess salt in the urine (salt wasting). Abnormalities of salt transport also affect the reabsorption of other ions, including ions of potassium, magnesium, and calcium. The resulting imbalance of ions in the body underlies the major features of Gitelman syndrome.

Gitelman syndrome inheritance pattern

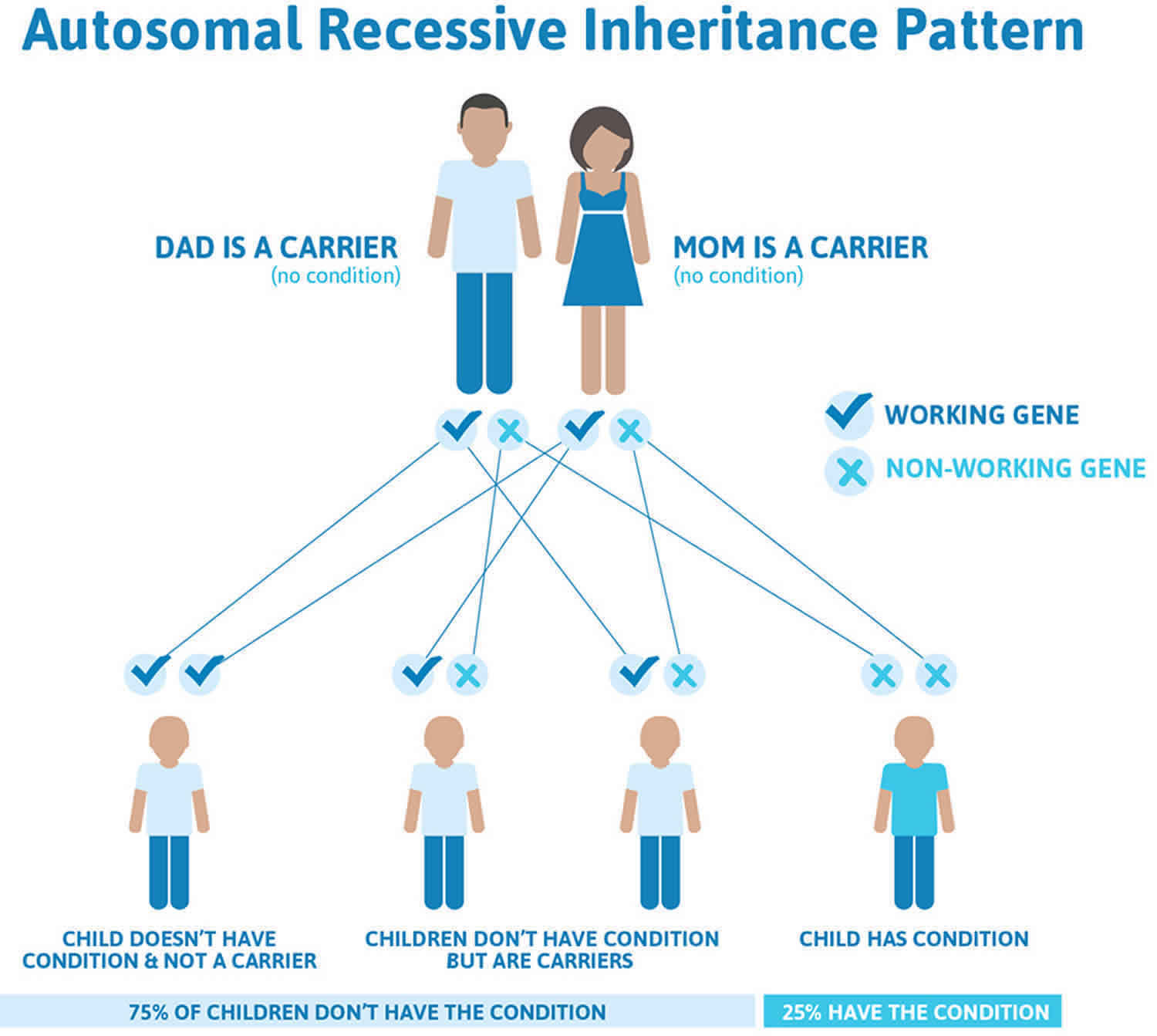

Gitelman syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of the gene in each cell have mutations. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive condition each carry one copy of the mutated gene, but they typically do not show signs and symptoms of the condition.

It is rare to see any history of autosomal recessive conditions within a family because if someone is a carrier for one of these conditions, they would have to have a child with someone who is also a carrier for the same condition. Autosomal recessive conditions are individually pretty rare, so the chance that you and your partner are carriers for the same recessive genetic condition are likely low. Even if both partners are a carrier for the same condition, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the non-working copy of the gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition. This chance is the same with each pregnancy, no matter how many children they have with or without the condition.

- If both partners are carriers of the same abnormal gene, they may pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. This occurs randomly.

- Each child of parents who both carry the same abnormal gene therefore has a 25% (1 in 4) chance of inheriting a abnormal gene from both parents and being affected by the condition.

- This also means that there is a 75% ( 3 in 4) chance that a child will not be affected by the condition. This chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys or girls.

- There is also a 50% (2 in 4) chance that the child will inherit just one copy of the abnormal gene from a parent. If this happens, then they will be healthy carriers like their parents.

- Lastly, there is a 25% (1 in 4) chance that the child will inherit both normal copies of the gene. In this case the child will not have the condition, and will not be a carrier.

These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

Figure 1 illustrates autosomal recessive inheritance. The example below shows what happens when both dad and mum is a carrier of the abnormal gene, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the abnormal gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition.

Figure 1. Gitelman syndrome autosomal recessive inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Gitelman syndrome symptoms

Signs and symptoms of Gitelman syndrome tend to present in adolescents and adults, but occasionally present in infants and young children (usually over the age of six). Gitelman syndrome signs and symptoms in children and adults are highly variable, even among individuals in the same family. Some people do not develop any symptoms (asymptomatic), while others can develop chronic issues that can impact their quality of life.

Signs and symptoms of Gitelman syndrome may include:

- A preference for salty foods (salt craving)

- Muscle weakness

- Fatigue

- Limited sports performance or endurance

- Episodes of fainting

- Cramps

- Muscle spasms

- Numbness or tingling (such as of the face)

- Growth delay

- Delayed puberty

- Short stature

- Excessive thirst

- Abdominal pain

Muscle weakness, spasms, and cramps may occur and generally are more common in Gitelman syndrome than the related Bartter syndrome. Affected individuals may experiences episodes of fatigue, dizziness, fainting (due to low blood pressure), muscle weakness, muscle aches, cramps and spasms. Affected individuals may also experience a specific form of cramping spasms called tetany. Tetany is marked by cramping spasms of certain muscles, particularly those of the hands and feet, arms, legs and/or face. Tetany may be provoked by hyperventilation during periods of anxiety.

Adults with Gitelman syndrome may also experience dizziness, vertigo, excessive amount of urine, urinating more at night, heart palpitations, joint pain, and vision problems 2.

Other possible symptoms include low blood pressure, a painful joint condition called, chondrocalcinosis, prolonged QT interval (a rare heart problem that may cause irregular heartbeat, fainting, or sudden death), episodes of elevated body temperature, vomiting, constipation, bed wetting, and paralysis 2. Additional rare symptoms have been described in single cases 2.

Symptomatic episodes may also be accompanied by abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and fever. Vomiting or diarrhea in a patient with Gitelman syndrome may lead to the misdiagnosis of eating disorder or cathartic abuse as the cause of hypokalemia. Falsely accusing a patient with Gitelman or Bartter syndrome of these behaviors can cause loss of trust as well as adverse psychological and emotional consequences. Measurement of urinary chloride will help differentiate Gitelman syndrome (high urinary chloride) from hypokalemia resulting from GI fluid losses. (urine chloride < 10 meQ/L). Seizures may also occur and in some people may be the initial reason they seek medical assistance. A loss of sensation or feeling of the face (facial paresthesia) characterized by numbness or tingling is common. Less often, tingling or numbness may affect the hands. The severity of fatigue can vary widely. Some individuals are severely fatigued to the point where it interferes with daily activities; other individuals never report fatigue as a specific symptom.

Affected individuals may or may not experience excessive thirst (polydipsia) and a frequent need to urinate (polyuria) including the excessive need to urinate at night (nocturia). When these symptoms do occur they are usually mild. Blood pressure can be abnormally low (hypotension) in comparison to the general population. Affected individuals often crave salt or high-salt foods. Salt craving frequently begins in childhood and is helpful in making a correct diagnosis.

Some affected adults develop chondrocalcinosis, a condition characterized by the accumulation of calcium in the joints. Its development is thought to be related to hypomagnesemia. Affected joints may be swollen, tender, reddened, and warm to the touch. In some individuals, chondrocalcinosis and its complications are the only symptoms that develop.

Gitelman syndrome is generally considered to be a milder variant of Bartter syndrome, with symptoms often overlapping with Bartter syndrome type 3 (classic Bartter syndrome). Renal salt wasting is more severe and begins earlier in life in Bartter syndrome than in Gitelman syndrome. However, researchers have determined that in rare cases more severe complications can occur in the newborn (neonatal) period. In these cases, affected infants experience severe hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia, which can be associated with an increased need to urinate and passage of large amounts of urine (polyuria), diminished muscle tone (hypotonia), muscle spasms, growth delays and a failure to grow and gain weight as would be expected based on age and gender (failure to thrive). Earlier-onset, more severe cases have occurred in greater frequency in male infants than female infants.

In affected individuals who experience significant electrolyte imbalances, irregular heartbeats (cardiac arrhythmias) may develop. Although rare, if untreated, these cardiac arrhythmias can potentially progress to cause sudden cardiac arrest and potentially sudden death. These cardiac issues result from a prolonged QT interval. The QT-interval is measured on the electrocardiogram and, if prolonged, indicates that the heart muscle is taking longer than usual to recharge between beats.

Some affected individuals may develop the breakdown of muscle tissue causing the release of toxic content of muscle cells into the body fluids (rhabdomyolysis). Rhabdomyolysis is a serious condition that can potentially damage the kidneys. Additional symptoms have been reported in the medical literature but are quite rare. These symptoms include blurred vision, vertigo, and an impaired ability to coordinate voluntary movements (ataxia). A study from Yale indicated that Gitelman and Bartter syndrome have significant impact to quality of life 5.

In a study of a series of individuals with Gitelman syndrome 6, it was determined that affected individuals can develop abnormally high blood pressure (hypertension) later during life (median 55 years of age). This is counterintuitive in a salt-wasting disorder that can cause low blood pressure earlier in life. The exact reason for the development of hypertension is unknown, but may be related to prolonged exposure to renin and aldosterone levels (see Causes section below) and often occurs in the presence of traditional risk factors for hypertension. Some women have experienced severe potassium wasting during pregnancy and have required increased potassium and magnesium supplementation.

Gitelman syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome may be suspected in children and adults with characteristic symptoms. A number of blood and urine tests aid in the diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome, such as 2:

- Potassium urine test

- Blood gases

- Blood tests to measure magnesium, aldosterone, and renin

- Urine analysis for sodium, potassium, and calcium

Common blood and urine abnormalities found in Gitelman syndrome, include:

- Low levels of potassium in the blood (hypokalemia)

- Metabolic alkalosis (too much base in the body)

- Low magnesium in the blood (hypomagnesemia)

- Low levels of calcium in the urine (hypocalciuria)

Anorexia, bulimia, chronic diarrhea, vomiting, and long term use of laxatives or diuretics can cause similar signs and symptoms. Before a diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome is made these conditions must be ruled out. A careful review of the patient and family health histories, as well as renal ultrasound findings can be helpful in ruling out other causes.

Molecular genetic testing can confirm a diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome. Genetic testing can detect mutations in the specific genes known to cause the disorder, but is available only as a diagnostic service at specialized laboratories. Generally, genetic testing is not needed to make a diagnosis.

Diagnostic criteria for Gitelman syndrome

Criteria for suspecting a diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome 2:

- Chronic hypokalemia (<3.5 mmol/l) with inappropriate renal potassium wasting (spot potassium-creatinine ratio >2.0 mmol/mmol [>18 mmol/g])

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Hypomagnesemia (<0.7 mmol/l [<1.70 mg/dl]) with inappropriate renal magnesium wasting (fractional excretion of magnesium >4%)

- Hypocalciuria (spot calcium-creatinine ratio <0.2 mmol/mmol [<0.07 mg/mg]) in adults.

- High plasma renin activity or levels

- Fractional excretion of chloride > 0.5%

- Low or normal-low blood pressure

- Normal renal ultrasound

Features against a diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome 2:

- Use of thiazide diuretics or laxatives

- Family history of kidney disease transmitted in an autosomal dominant mode

- Absence of hypokalemia (unless renal failure); inconsistent hypokalemia in absence of substitutive therapy

- Absence of metabolic alkalosis (unless coexisting bicarbonate loss or acid gain)

- Low renin values

- Urine: low urinary potassium excretion (spot potassium-creatinine ratio <2.0 mmol/mmol [<18 mmol/g]); hypercalciuria

- Hypertension,c manifestations of increased extracellular fluid volume

- Renal ultrasound: nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, unilateral kidneys, cystic kidneys

- Prenatal history of polyhydramnios, hyperechogenic kidneys

- Presentation before age 3 years (hypertension and presentation before age 3 years do not exclude Gitelman syndrome)

Gitelman syndrome treatment

The treatment of Gitelman syndrome is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual. Treatment may require the coordinated efforts of a team of specialists. Pediatricians or general internists, kidney specialists (nephrologists or pediatric nephrologists), cardiologists, social workers and other healthcare professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan individual’s treatment. Genetic counseling may be of benefit for affected individuals and their families. Because this is a rare disease, even well trained private practice or academic nephrologists may have little experience diagnosing or treating this disease.

Individuals who do not develop symptoms (asymptomatic) often do not require treatment, but it is recommended that they receive outpatient monitoring one or twice a year. They should be aware that they will be prone to rapidly become dehydrated should they experience vomiting or diarrhea from gastrointestinal illness. They may require saline and intravenous potassium supplementation during these illnesses. All individuals with Gitelman syndrome are encouraged to follow a high-sodium chloride added diet. Dietary potassium should also be high. Dried fruit is an excellent source of supplemental potassium. Such a diet can help reduce exposure to potassium chloride supplements which irritate the stomach lining. These patents should never be treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARBs).

There is no cure for Gitelman syndrome. The mainstay of treatment for affected individuals is a high salt diet with oral potassium and magnesium supplements. Potassium rich foods such as dried fruit are helpful. Magnesium supplements in single large doses cause diarrhea and should be avoided. Magnesium supplements should be taken in small frequent (4-6 times/ day) in order to avoid magnesium associated diarrhea which may worsen hypokalemia and symptoms of volume depletion. For many individuals, lifelong daily supplementation with magnesium is recommended. In some cases, during severe muscle cramps, magnesium has been given intravenously. In general, the goal of therapy should always be attenuation of symptoms rather than normalization of electrolyte abnormalities. Because of the risk of infection and thrombosis, central catheters should be discouraged.

Some affected individuals may receive medications known as potassium-sparing diuretics such as spironolactone, eplerenone or amiloride. These drugs are mild diuretics that spare potassium excretion. While these agents improve hypokalemia, they rarely normalize serum potassium concentrations. The goal of therapy is to improve symptoms not to normalize laboratory abnormalities. When chondrocalcinosis causes symptoms, supplementation with magnesium, pain medications and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen may be beneficial.

A specific nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) known as indomethacin has been used to treat some infants and children with Gitelman syndrome. This drug is commonly used to treat individuals with Bartter syndrome, but is being used more often in Gitelman syndrome, particularly to treat growth deficiency in severe, early-onset forms of the disorder.

Affected individuals may be encouraged to undergo a cardiac workup to screen for risk factors for cardiac arrhythmias. Individuals with a prolonged QT interval should avoid drugs that prolong the QT interval. For a list of such drugs, contact the Sudden Arrhythmia Death Syndromes Foundation (https://www.sads.org/living-with-sads/Drugs-to-Avoid).

Gitelman syndrome prognosis

The long-term outlook (prognosis) for people with Gitelman syndrome is generally very good 7. However, the symptoms and severity can vary from person to person. Some people do not develop any symptoms, while others develop chronic issues that can impact their quality of life 4. Weakness, fatigue and muscle cramping can affect daily activities in some people with Gitelman syndrome 4. In general, while the underlying condition does not appear to be progressive, complications can arise, especially if care recommendations are not followed.

Progressive renal insufficiency is extremely rare 8. Renal function is usually maintained despite long-term hypokalemia (low potassium), but progression to chronic renal insufficiency has rarely been reported 8.

Some people with Gitelman syndrome may be at risk of developing cardiac arrhythmias. Those with severe hypokalemia are more susceptible to cardiac arrhythmias, which can be life-threatening when joined with severe hypomagnesemia (low magnesium) and alkalosis 7. Therefore, an in-depth cardiac work-up is strongly recommended to identify which people with Gitelman syndrome may be at risk 7. Competitive sports should be avoided because sudden death can be precipitated by intense physical activity that induces potassium and magnesium loss by sweating 7.

References- Gitelman syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/gitelman-syndrome

- Gitelman syndrome: consensus and guidance from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Blanchard, Anne et al. Kidney International, Volume 91, Issue 1, 24 – 33 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.046

- Knoers, N.V., Levtchenko, E.N. Gitelman syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 3, 22 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-3-22

- Gitelman Syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/gitelman-syndrome

- Cruz AJ, Castro A. Gitelman or Bartter type 3 syndrome? A case of distal convoluted tubulopathy caused by CLCNKB gene mutation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3604527

- Berry MR, Robinson C, Karet Frankl FE. Unexpected clinical sequelae of Gitelman syndrome: hypertension in adulthood is common and females have higher potassium requirements. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(6):1533–1542. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfs600

- Graziani G, Fedeli C, Moroni L, Cosmai L, Badalamenti S, Ponticelli C. Gitelman syndrome: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. QJM. October, 2010; 103(10):741-748. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20650971

- Lee JH, Lee J, Han JS. Gitelman’s syndrome with vomiting manifested by severe metabolic alkalosis and progressive renal insufficiency. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013; 231(3):165-169. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24162365