Glenohumeral arthritis

Glenohumeral arthritis is defined as shoulder joint arthritis, which is an inflammation your shoulder joint or glenohumeral joint. Glenohumeral arthritis causes pain and stiffness. Although there is no cure for arthritis of the shoulder, there are many treatment options available. Using these, most people with arthritis are able to manage pain and stay active.

There are five major types of arthritis typically affect the shoulder:

- Glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis

- Glenohumeral joint rheumatoid arthritis

- Glenohumeral joint posttraumatic arthritis

- Rotator cuff tear arthropathy

- Avascular necrosis

Research is being conducted on glenohumeral arthritis and its treatment.

- In many cases, it is not known why some people develop arthritis and others do not. Research is being done to uncover some of the causes of arthritis of the shoulder.

- Joint lubricants, which are currently being used for treatment of knee arthritis, are being studied in the shoulder.

- New medications to treat rheumatoid arthritis are being investigated.

- Much research is being done on shoulder joint replacement surgery, including the development of different joint prosthesis designs.

- The use of biologic materials to resurface an arthritic shoulder is also being studied. Biologic materials are tissue grafts that promote growth of new tissue in the body and foster healing.

Shoulder anatomy

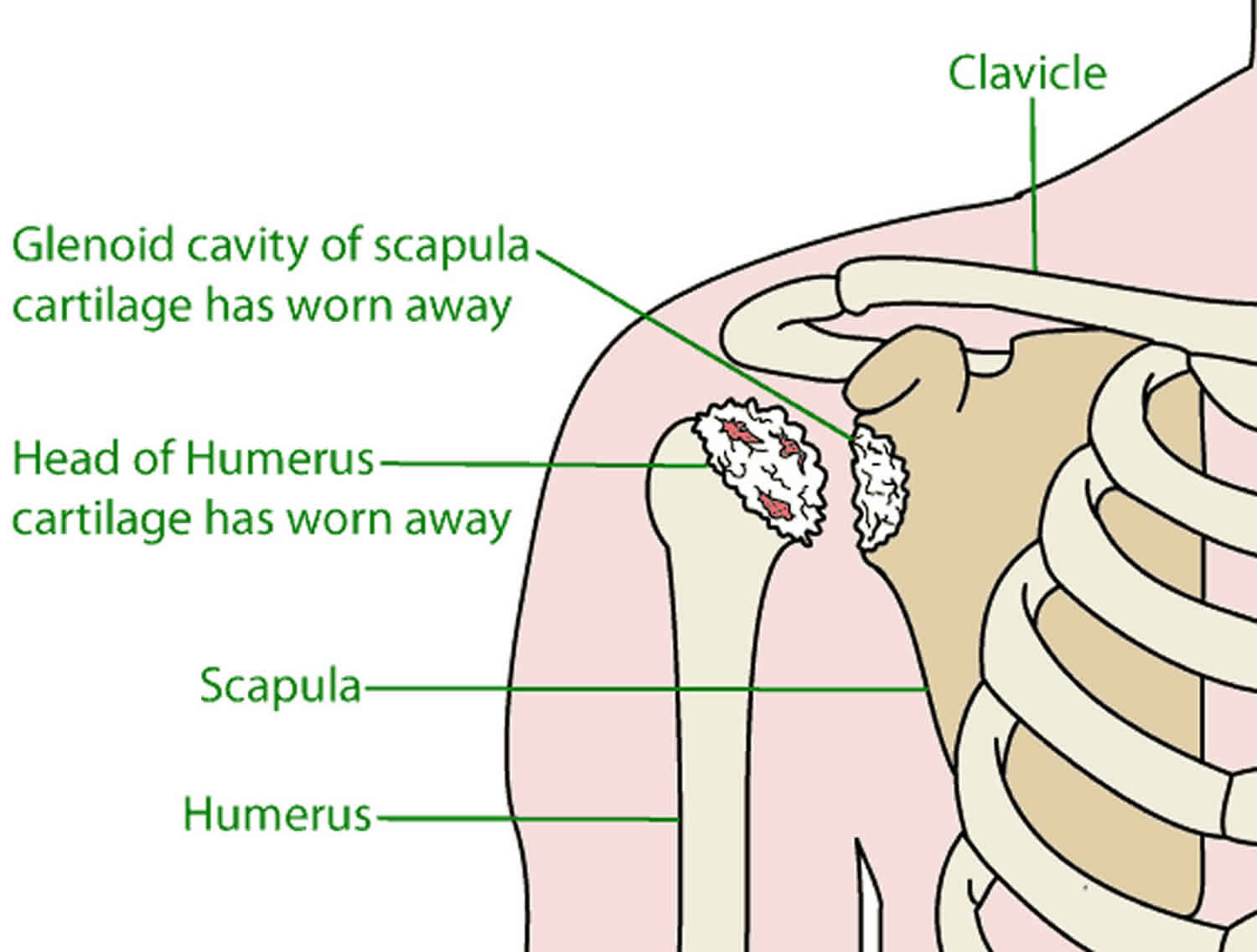

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

The head of your upper arm bone fits into a rounded socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. A combination of muscles and tendons keeps your arm bone centered in your shoulder socket. These tissues are called the rotator cuff.

There are two joints in the shoulder, and both may be affected by arthritis. One joint is located where the collarbone (clavicle) meets the tip of the shoulder blade (acromion). This is called the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

The glenohumeral joint forms where the head of your upper arm bone (humerus) fits into your shoulder blade (scapula).

To provide you with effective treatment, your physician will need to determine which joint is affected and what type of arthritis you have.

Figure 1. Shoulder anatomy

Glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis

In glenohumeral osteoarthritis or shoulder joint osteoarthritis also called degenerative joint disease or “wear-and-tear” arthritis, your cartilage and other shoulder joint tissues gradually break down. As the cartilage wears away, it becomes frayed and rough, and the protective space between the bones decreases. During movement, the bones of the joint rub against each other, causing pain. Friction in the glenohumeral joint increases, pain increases, and you slowly lose mobility and function. Glenohumeral osteoarthritis is not as common as osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, but it is estimated that nearly 1 in 3 people over the age of 60 have shoulder osteoarthritis to some degree. Osteoarthritis is more common in the acromioclavicular joint than the glenohumeral joint.

Glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis causes

Shoulder osteoarthritis can be either primary or secondary.

- Primary osteoarthritis has no specific cause but is related to age, genes and sex. Primary osteoarthritis is usually seen in people over the age of 50, and women are affected more often than men.

- Secondary osteoarthritis has a known cause or influencing factor, such as previous injury, history of shoulder dislocations, infection, or rotator cuff tears. Having certain occupations — such as heavy construction – or participating in overhead sports can also put you at higher risk of developing shoulder osteoarthritis.

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis symptoms

Pain is the most common symptom of shoulder arthritis. Pain is aggravated by activity and gets worse over time. As the disease progresses, the pain will continue when you are at rest and will begin to interfere with sleep.

- If the glenohumeral shoulder joint is affected, the pain will be felt at the back of the shoulder and may feel like a deep ache.

- If the acromioclavicular joint is affected, pain will be focused on the top of the shoulder. This pain may radiate up the side of the neck.

Limited motion and stiffness are other common symptoms. You may lose range of motion so that you can’t lift your arm to wash your hair or get something down off a shelf.

Crepitus is when you hear and feel grinding and clicking noises as you move your shoulder.

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis diagnosis

To diagnose shoulder osteoarthritis, your doctor will ask about your symptoms and medical history. During the exam she will look for:

- Muscle strength

- Tenderness to the touch

- Mobility – both active and passive range of motion

- Signs of new or old injuries

- Other joints with signs of arthritis

- Crepitus (a grating sensation inside the joint) with movement

- Pain in certain positions

- Swelling or joint enlargement

After the physical exam, your doctor will likely order X-rays. If you have osteoarthritis, they will show joint-space narrowing, changes in the bone, and the formation of bone spurs (osteophytes).

Glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis treatment

Osteoarthritis is a chronic disease. There is no cure, but treatments can help manage your symptoms and keep you active.

Non-pharmacologic treatments

If you have shoulder osteoarthritis, start with the basics of self-care to manage your symptoms.

- Change your activities. You may need to alter the way you move your arm to avoid pain.

- Do physical therapy and rehab exercises. Stretch and strengthen the muscles that support your shoulder to reduce stress on the joint. These exercises may also improve your range of motion.

- Try heat or cold. Apply an ice pack for 20 minutes two or three times a day to reduce inflammation and ease pain. Or wrap your shoulder in a warm, wet towel or a heating pad to soothe your joint and improve mobility.

- Seek complementary treatments. Acupuncture, massage, or yoga may help improve mobility and pain.

Medications

Medicines to ease osteoarthritis symptoms are available as pills, syrups, creams or lotions, or they are injected into a joint. They include:

- Pain relievers like acetaminophen and anti-inflammatories like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used to ease pain.

- Topical analgesics such as NSAID gels, capsaicin or counterirritants can be rubbed into the shoulder to reduce pain.

- Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory medicines that can be injected into the shoulder joint. An injection can dramatically reduce inflammation and pain, but only helps temporarily.

Surgical treatments

You and your doctor may consider surgery if your pain and mobility are not improved with physical therapy and medicine.

Arthroscopy can be used to clean out the inside of the joint, removing bone spurs and loose pieces of cartilage. Arthroscopy provides pain relief, but it will not eliminate your arthritis.

Joint replacement (arthroplasty) can be done if you have advanced arthritis in your glenohumeral joint. In this, the head of the humerus is replaced with an artificial “ball” and the glenoid cup is replaced with a synthetic part. In hemiarthroplasty, just the head of the humerus is replaced, but the cup is left alone.

Resection arthroplasty is used to treat advanced osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. In this procedure, a small piece of bone from the end of the collarbone is removed. That space will gradually fill with scar tissue.

Glenohumeral joint rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system – which normally protects its health by attacking foreign substances like bacteria and viruses – mistakenly attacks the joints such as cartilage and ligaments and soften bone. The joints of your body are covered with a lining — called synovium — that lubricates the joint and makes it easier to move. Rheumatoid arthritis causes the synovium to swell, which causes pain in and around the joints and stiffness in the joint.

Rheumatoid arthritis a chronic disease that attacks multiple joints throughout the body. Rheumatoid arthritis is symmetrical, meaning that it usually affects the same joint on both sides of the body.

If inflammation goes unchecked, it can damage cartilage, the elastic tissue that covers the ends of bones in a joint, as well as the bones themselves. Over time, there is loss of cartilage, and the joint spacing between bones can become smaller. Joints can become loose, unstable, painful and lose their mobility. Joint deformity also can occur. Joint damage cannot be reversed, and because it can occur early, doctors recommend early diagnosis and aggressive treatment to control rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis most commonly affects the joints of the hands, feet, wrists, elbows, knees and ankles. The joint effect is usually symmetrical. That means if one knee or hand if affected, usually the other one is, too. Rheumatoid arthritis is equally common in both joints of the shoulder. Because rheumatoid arthritis also can affect body systems, such as the cardiovascular or respiratory systems, it is called a systemic disease. Systemic means “entire body.”

About 1.5 million people in the United States have rheumatoid arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis). Nearly three times as many women have the disease as men. In women, rheumatoid arthritis most commonly begins between ages 30 and 60. In men, it often occurs later in life. Having a family member with rheumatoid arthritis increases the odds of having rheumatoid arthritis; however, the majority of people with rheumatoid arthritis have no family history of the disease.

Glenohumeral joint rheumatoid arthritis causes

The cause of rheumatoid arthritis is not yet fully understood, although doctors do know that an abnormal response of the immune system plays a leading role in the inflammation and joint damage that occurs. No one knows for sure why the immune system goes awry, but there is scientific evidence that genes, hormones and environmental factors are involved.

Researchers have shown that people with a specific genetic marker called the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) shared epitope have a fivefold greater chance of developing rheumatoid arthritis than do people without the marker. The HLA genetic site controls immune responses. Other genes connected to rheumatoid arthritis include: STAT4, a gene that plays important roles in the regulation and activation of the immune system; TRAF1 and C5, two genes relevant to chronic inflammation; and PTPN22, a gene associated with both the development and progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Yet not all people with these genes develop rheumatoid arthritis and not all people with the condition have these genes.

Researchers continue to investigate other factors that may play a role. These factors include infectious agents such as bacteria or viruses, which may trigger development of the disease in a person whose genes make them more likely to get it; female hormones (70 percent of people with rheumatoid arthritis are women); obesity; and the body’s response to stressful events such as physical or emotional trauma. Research also has indicated that environmental factors may play a role in one’s risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Some include exposure to cigarette smoke, air pollution, insecticides and occupational exposures to mineral oil and silica.

Glenohumeral joint rheumatoid arthritis symptoms

In the early stages, people with rheumatoid arthritis may not initially see redness or swelling in the joints, but they may experience tenderness and pain.

These following joint symptoms are clues to rheumatoid arthritis:

- Joint pain, tenderness, swelling or stiffness for six weeks or longer

- Morning stiffness for 30 minutes or longer

- More than one joint is affected

- Small joints (wrists, certain joints of the hands and feet) are affected

- The same joints on both sides of the body are affected

Along with pain, many people experience fatigue, loss of appetite and a low-grade fever.

The symptoms and effects of rheumatoid arthritis may come and go. A period of high disease activity (increases in inflammation and other symptoms) is called a flare. A flare can last for days or months.

Ongoing high levels of inflammation can cause problems throughout the body. Here of some ways rheumatoid arthritis can affect organs and body systems:

- Eyes. Dryness, pain, redness, sensitivity to light and impaired vision

- Mouth. Dryness and gum irritation or infection

- Skin. Rheumatoid nodules – small lumps under the skin over bony areas

- Lungs. Inflammation and scarring that can lead to shortness of breath

- Blood Vessels. Inflammation of blood vessels that can lead to damage in the nerves, skin and other organs

- Blood. Anemia, a lower than normal number of red blood cells

Glenohumeral joint rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis

A primary care physician may suspect rheumatoid arthritis based in part on a person’s signs and symptoms. If so, the patient will be referred to a rheumatologist – a specialist with specific training and skills to diagnose and treat rheumatoid arthritis. In its early stages, rheumatoid arthritis may resemble other forms of inflammatory arthritis. No single test can confirm rheumatoid arthritis. To make a proper diagnosis, the rheumatologist will ask questions about personal and family medical history, perform a physical exam and order diagnostic tests.

Your doctor will ask about your personal and family medical history as well as recent and current symptoms (pain, tenderness, stiffness, difficulty moving).

Physical exam

Your doctor will examine each joint, looking for tenderness, swelling, warmth and painful or limited movement. The number and pattern of joints affected can also indicate rheumatoid arthritis. For example, rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect joints on both sides of the body. The physical exam may reveal other signs, such as rheumatoid nodules or a low-grade fever.

Blood tests

The blood tests will measure inflammation levels and look for biomarkers such as antibodies (blood proteins) linked with rheumatoid arthritis.

Inflammation

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, or “sed rate”) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level are markers of inflammation. A high ESR or CRP is not specific to rheumatoid arthritis, but when combined with other clues, such as antibodies, helps make the rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis.

Antibodies

Rheumatoid factor (RF) is an antibody found in about 80 percent of people with rheumatoid arthritis during the course of their disease. Because rheumatoid factor can occur in other inflammatory diseases, it’s not a sure sign of having rheumatoid arthritis. But a different antibody – anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) – occurs primarily in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. That makes a positive anti-CCP test a stronger clue to rheumatoid arthritis. But anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies are found in only 60 to 70 percent of people with rheumatoid arthritis and can exist even before symptoms start.

Imaging tests

An X-ray, ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be done to look for joint damage, such as erosions – a loss of bone within the joint – and narrowing of joint space. But if the imaging tests don’t show joint damage that doesn’t rule out rheumatoid arthritis. It may mean that the disease is in an early stage and hasn’t yet damaged the joints.

Glenohumeral joint rheumatoid arthritis treatment

The goals of rheumatoid arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis) treatment are to:

- Stop inflammation (put disease in remission)

- Relieve symptoms

- Prevent joint and organ damage

- Improve physical function and overall well-being

- Reduce long-term complications

To meet these goals, the doctor will follow these strategies:

- Early, aggressive treatment. The first strategy is to reduce or stop inflammation as quickly as possible – the earlier, the better.

- Targeting remission. Doctors refer to inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis as disease activity. The ultimate goal is to stop it and achieve remission, meaning minimal or no signs or symptoms of active inflammation. One strategy to achieve this goal is called “treat to target.”

- Tight control. Getting disease activity to a low level and keeping it there is what is called having “tight control of rheumatoid arthritis.” Research shows that tight control can prevent or slow the pace of joint damage.

Self-care

Self-care or self-management, means taking a proactive role in treatment and maintaining a good quality of life. Here are some ways you can manage rheumatoid arthritis symptoms (along with recommended medication) and promote overall health.

Anti-inflammatory diet and healthy eating

While there is no specific “diet” for rheumatoid arthritis, researchers have identified certain foods that are rich in antioxidants and can help control and reduce inflammation. Many of them are part of the so-called Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes fish, vegetables, fruits and olive oil, among other healthy foods. It’s also important to eliminate or significantly reduce processed and fast foods that fuel inflammation.

Balancing activity with rest

Rest is important when rheumatoid arthritis is active and joints feel painful, swollen or stiff. Rest helps reduce inflammation and fatigue that can come with a flare. Taking breaks throughout the day conserves energy and protects joints.

Physical activity

For people with rheumatoid arthritis, exercise is so beneficial it’s considered a main part of rheumatoid arthritis treatment. The exercise program should emphasize low-impact aerobics, muscle strengthening and flexibility. The program should be tailored to fitness level and capabilities, and take into account any joint damage that exists. A physical therapist can help to design an exercise program.

Heat and cold therapies

Heat treatments, such as heat pads or warm baths, tend to work best for soothing stiff joints and tired muscles. Cold is best for acute pain. It can numb painful areas and reduce inflammation.

Topical treatments

These treatments are applied directly to the skin over the painful muscle or joint. They may be creams or patches. Depending on the type used, it may contain nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), salicylates or capsaicin, which help reduce pain.

Natural and alternative therapies

Relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing, guided imagery and visualization can help train painful muscles to relax. Research shows massage can help reduce arthritis pain, improve joint function and ease stress and anxiety. Acupuncture may also be helpful. This involves inserting fine needles into the body along special points called “meridians” to relieve pain. Those who fear needles might consider acupressure, which involves applying pressure, instead of needles, at those points.

Supplements

Studies have shown that turmeric and omega-3 fish oil supplements may help with rheumatoid arthritis pain and morning stiffness. However, talk with a doctor before taking any supplement to discuss side effects and potential interactions.

Positive attitude and support system

Many studies have demonstrated that resilience, an ability to “bounce back,“ encourages a positive outlook. Having a network of friends, family members and co-workers can help provide emotional support. It can help a patient with rheumatoid arthritis cope with life changes and pain.

Medications for rheumatoid arthritis

There are different drugs used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Some are used primarily to ease the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis; others are used to slow or stop the course of the disease and to inhibit structural damage.

Drugs that ease symptoms

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are available over-the-counter and by prescription. They are used to help ease arthritis pain and inflammation. NSAIDs include such drugs as ibuprofen, ketoprofen and naproxen sodium, among others. For people who have had or are at risk of stomach ulcers, the doctor may prescribe celecoxib, a type of NSAID called a COX-2 inhibitor, which is designed to be safer for the stomach. These medicines can be taken by mouth or applied to the skin (as a patch or cream) directly to a swollen joint.

Drugs that slow disease activity

- Corticosteroids. Corticosteroid medications, including prednisone, prednisolone and methyprednisolone, are potent and quick-acting anti-inflammatory medications. They may be used in rheumatoid arthritis to get potentially damaging inflammation under control, while waiting for NSAIDs and DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) to take effect. Because of the risk of side effects with these drugs, doctors prefer to use them for as short a time as possible and in doses as low as possible.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). DMARDs are drugs that work to modify the course of the disease. Traditional DMARDs include methotrexate, hydroxycholorquine, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, cyclophosphamide and azathioprine. These medicines can be taken by mouth, be self-injected or given as an infusion in a doctor’s office.

- Biologics. These drugs are a subset of DMARDs. Biologics may work more quickly than traditional DMARDs, and are injected or given by infusion in a doctor’s office. Because they target specific steps in theinflammatory process, they don’t wipe out the entire immune response as some other rheumatoid arthritis treatments do. In many people with rheumatoid arthritis, a biologic can slow, modify or stop the disease – even when other treatments haven’t helped much.

- JAK inhibitors. A new subcategory of DMARDs known as “JAK inhibitors” block the Janus kinase, or JAK, pathways, which are involved in the body’s immune response. Tofacitinib belongs to this class. Unlike biologics, it can be taken by mouth.

Surgery

Surgery for rheumatoid arthritis may never be needed, but it can be an important option for people with permanent damage that limits daily function, mobility and independence. Joint replacement surgery can relieve pain and restore function in joints badly damaged by rheumatoid arthritis. The procedure involves replacing damaged parts of a joint with metal and plastic parts. Hip and knee replacements are most common. However, ankles, shoulders, wrists, elbows, and other joints may be considered for replacement.

Glenohumeral joint posttraumatic arthritis

Posttraumatic arthritis is a form of osteoarthritis that develops after an injury, such as a fracture or dislocation of the shoulder.

Glenohumeral joint rotator cuff tear arthropathy

Arthritis can also develop after a large, long-standing rotator cuff tendon tear. The torn rotator cuff can no longer hold the head of the humerus in the glenoid socket, and the humerus can move upward and rub against the acromion. This can damage the surfaces of the bones, causing arthritis to develop.

The combination of a large rotator cuff tear and advanced arthritis can lead to severe pain and weakness, and the patient may not be able to lift the arm away from the side.

Glenohumeral joint avascular necrosis

Avascular necrosis of the shoulder is a painful condition that occurs when the blood supply to the head of the humerus is disrupted. Because bone cells die without a blood supply, avascular necrosis can ultimately lead to destruction of the shoulder joint and arthritis.

Avascular necrosis develops in stages. As it progresses, the dead bone gradually collapses, which damages the articular cartilage covering the bone and leads to arthritis. At first, avascular necrosis affects only the head of the humerus, but as avascular necrosis progresses, the collapsed head of the humerus can damage the glenoid socket.

Causes of avascular necrosis include high dose steroid use, heavy alcohol consumption, sickle cell disease, and traumatic injury, such as fractures of the shoulder. In some cases, no cause can be identified; this is referred to as idiopathic avascular necrosis.

Glenohumeral arthritis symptoms

Pain

The most common symptom of arthritis of the shoulder is pain, which is aggravated by activity and progressively worsens.

- If the glenohumeral shoulder joint is affected, the pain is centered in the back of the shoulder and may intensify with changes in the weather. Patients complain of an ache deep in the joint.

- The pain of arthritis in the acromioclavicular joint is focused on the top of the shoulder. This pain can sometimes radiate or travel to the side of the neck.

- Someone with rheumatoid arthritis may have pain throughout the shoulder if both the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints are affected.

Limited range of motion

Limited motion is another common symptom. It may become more difficult to lift your arm to comb your hair or reach up to a shelf. You may hear a grinding, clicking, or snapping sound (crepitus) as you move your shoulder.

As the disease progresses, any movement of the shoulder causes pain. Night pain is common and sleeping may be difficult.

Glenohumeral arthritis diagnosis

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder.

During the physical examination, your doctor will look for:

- Weakness (atrophy) in the muscles

- Tenderness to touch

- Extent of passive (assisted) and active (self-directed) range of motion

- Any signs of injury to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the joint

- Signs of previous injuries

- Involvement of other joints (an indication of rheumatoid arthritis)

- Crepitus (a grating sensation inside the joint) with movement

- Pain when pressure is placed on the joint

X-rays

X-rays are imaging tests that create detailed pictures of dense structures, like bone. They can help distinguish among various forms of arthritis.

X-rays of an arthritic shoulder will show a narrowing of the joint space, changes in the bone, and the formation of bone spurs (osteophytes).

To confirm the diagnosis, your doctor may inject a local anesthetic into the joint. If it temporarily relieves the pain, the diagnosis of arthritis is supported.

Glenohumeral arthritis treatment

Nonsurgical treatment

As with other arthritic conditions, initial treatment of arthritis of the shoulder is nonsurgical. Your doctor may recommend the following treatment options:

- Rest or change in activities to avoid provoking pain. You may need to change the way you move your arm to do things.

- Physical therapy exercises may improve the range of motion in your shoulder.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may reduce inflammation and pain. These medications can irritate the stomach lining and cause internal bleeding. They should be taken with food. Consult with your doctor before taking over-the-counter NSAIDs if you have a history of ulcers or are taking blood thinning medication.

- Corticosteroid injections in the shoulder can dramatically reduce the inflammation and pain. However, the effect is often temporary.

- Moist heat

- Ice your shoulder for 20 to 30 minutes two or three times a day to reduce inflammation and ease pain.

- If you have rheumatoid arthritis, your doctor may prescribe a disease-modifying drug, such as methotrexate.

- Dietary supplements, such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate may help relieve pain. (Note: There is little scientific evidence to support the use of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate to treat arthritis. In addition, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration does not test dietary supplements. These compounds may cause negative interactions with other medications. Always consult your doctor before taking dietary supplements.)

Surgical treatment

Your doctor may consider surgery if your pain causes disability and is not relieved with nonsurgical options.

Arthroscopy

Cases of mild glenohumeral arthritis may be treated with arthroscopy, During arthroscopy, the surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into the shoulder joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and the surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments.

Because the arthroscope and surgical instruments are thin, the surgeon can use very small incisions (cuts), rather than the larger incision needed for standard, open surgery.

During the procedure, your surgeon can debride (clean out) the inside of the joint. Although the procedure provides pain relief, it will not eliminate the arthritis from the joint. If the arthritis progresses, further surgery may be needed in the future.

Shoulder joint replacement (arthroplasty)

Advanced arthritis of the glenohumeral joint can be treated with shoulder replacement surgery, in which the damaged parts of the shoulder are removed and replaced with artificial components, called a prosthesis.

Replacement surgery options include:

- Hemiarthroplasty. Just the head of the humerus is replaced by an artificial component.

- Total shoulder arthroplasty. Both the head of the humerus and the glenoid are replaced. A plastic “cup” is fitted into the glenoid, and a metal “ball” is attached to the top of the humerus.

- Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. In a reverse total shoulder replacement, the socket and metal ball are opposite a conventional total shoulder arthroplasty. The metal ball is fixed to the glenoid and the plastic cup is fixed to the upper end of the humerus. A reverse total shoulder replacement works better for people with cuff tear arthropathy because it relies on different muscles — not the rotator cuff — to move the arm.

Resection arthroplasty

The most common surgical procedure used to treat arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint is a resection arthroplasty. Your surgeon may choose to do this arthroscopically.

In this procedure, a small amount of bone from the end of the collarbone is removed, leaving a space that gradually fills in with scar tissue.

Recovery

Surgical treatment of arthritis of the shoulder is generally very effective in reducing pain and restoring motion. Recovery time and rehabilitation plans depend upon the type of surgery performed.

Pain management

After surgery, you will feel some pain. This is a natural part of the healing process. Your doctor and nurses will work to reduce your pain, which can help you recover from surgery faster.

Medications are often prescribed for short-term pain relief after surgery. Many types of medicines are available to help manage pain, including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. Your doctor may use a combination of these medications to improve pain relief, as well as minimize the need for opioids.

Be aware that although opioids help relieve pain after surgery, they are a narcotic and can be addictive. Opioid dependency and overdose has become a critical public health issue in the U.S. It is important to use opioids only as directed by your doctor. As soon as your pain begins to improve, stop taking opioids. Talk to your doctor if your pain has not begun to improve within a few days of your surgery.

Complications

As with all surgeries, there are some risks and possible complications. Potential problems after shoulder surgery include infection, excessive bleeding, blood clots, and damage to blood vessels or nerves.

Your surgeon will discuss the possible complications with you before your operation.