The Gluten Free Diet

Gluten free diet is a diet free of gluten. This is essentially a diet that removes all foods containing or contaminated with gluten. However, since gluten-containing whole grains contain fiber and nutrients including B vitamins, magnesium, and iron, it’s important to make up for these missing nutrients. Along with consuming naturally gluten-free foods in their whole form like fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, fish, eggs, and poultry, the following whole grains are also inherently gluten-free:

- Quinoa

- Brown, black, or red rice

- Buckwheat

- Amaranth

- Millet

- Corn

- Sorghum

- Teff

- Oats (when not contaminated during growing/processing)

Gluten free diet is a diet that is critical in treating celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy. Gluten is a protein found naturally in wheat, barley, and rye that triggers an immune reaction if you have celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy. Removing gluten from your diet will improve symptoms for most people, heal damage to your small intestine, and prevent further damage over time. While you may need to avoid certain gluten-foods, the good news is that many healthy, gluten-free foods and products are now available in grocery stores and restaurants, making it easier to stay gluten free.

It’s also key not to rely on processed gluten-free foods that may be high in calories, sugar, saturated fat, and sodium and low in nutrients, such as gluten-free cookies, chips, and other snack foods. Often, these foods are made with processed unfortified rice, tapioca, corn, or potato flours.

- If you are concerned about celiac disease, you are strongly discouraged from starting a gluten-free diet without having had a firm diagnosis by your medical doctor. And if you change your diet to the gluten free diet, even for as little as a month, can complicate the diagnostic process. This is because all celiac disease blood tests require that you be on a gluten-containing diet to be accurate.

Interestingly, studies show that people who do not have celiac disease are the biggest purchasers of gluten-free products 1. Consumer surveys show that the top three reasons people select gluten-free foods are for “no reason,” because they are a “healthier option,” and for “digestive health” 2. For those who are not gluten-intolerant, there is no data to show a specific benefit in following a gluten-free diet, particularly if processed gluten-free products become the mainstay of the diet. In fact, research following patients with celiac disease who change to a gluten-free diet shows an increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome. This could be partly due to improved intestinal absorption, but speculation has also focused on the low nutritional quality of processed gluten-free foods that may contain refined sugars and saturated fats and have a higher glycemic index 3, 4.

What is Gluten

Gluten comes from the Latin word for ‘glue’ which gives dough the elastic property that holds gas when it rises. Bubbles of carbon dioxide are released from fermenting yeast, which become trapped by the visco-elastic protein, ensuring a light honeycombed texture for the dough 5. The elastic nature of gluten also holds particles of the dough together, preventing crumbling during rolling and shaping. Hence, gluten plays a vital role in the production of leavened baked goods.

Gluten is the name given to the protein found in some, but not all, grains:

- Grains containing gluten – wheat (including wheat varieties like spelt, kamut, farro and durum, plus products like bulgar and semolina), barley, rye, triticale.

- Gluten-free grains – corn, millet, rice, oats (uncontaminated), sorghum.

- Gluten-free pseudo-cereals – amaranth, buckwheat, quinoa.

Gluten can be readily prepared by gently washing dough under a stream of running water. This removes the bulk of the soluble and particulate matter to leave a proteinaceous mass that retains its cohesiveness on stretching 6. Gluten is the term used to identify a mixture of proteins (prolamines) that occurs in the endosperm of wheat (gliadins) and other cereals such as barley (hordeins) and rye (secalins) 7. Gluten is found in wheat (wheatberries, durum, emmer, semolina, spelt, farina, farro, graham, KAMUT® khorasan wheat and einkorn), rye, barley and triticale – a cross between wheat and rye. Gluten helps foods maintain their shape, acting as a glue that holds food together. Gluten can be found in many types of foods, even ones that would not be expected.

Gluten is common in foods such as bread, pasta, cookies, and cakes. Many pre-packaged foods, lip balms and lipsticks, hair and skin products, toothpastes, vitamin and nutrient supplements, and, rarely, medicines, contain gluten.

Up to recently, the most common gluten-related disorders in children included only coeliac disease (celiac disease) and wheat allergy. To these, the entity known as non-coeliac gluten sensitivity has been added. The common feature among these gluten-associated disorders is their treatment: a gluten-free diet.

Gluten and Health Benefits

Gluten is most often associated with wheat and wheat-containing foods that are abundant in our food supply. Negative media attention on wheat and gluten has caused some people to doubt its place in a healthful diet. There is little published research to support these claims; in fact published research suggests the opposite.

In a 2017 study of over 100,000 participants without celiac disease, researchers found no association between long-term dietary gluten consumption and heart disease risk 8. In fact, the findings also suggested that non-celiac individuals who avoid gluten may increase their risk of heart disease, due to the potential for reduced consumption of whole grains.

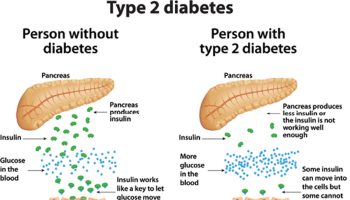

- Many studies have linked whole grain consumption with improved health outcomes. For example, groups with the highest intakes of whole grains including wheat (2-3 servings daily) compared with groups eating the lowest amounts (less than 2 servings daily) were found to have significantly lower rates of heart disease and stroke, development of type 2 diabetes, and deaths from all causes 9, 10, 11, 12.

Gluten may also act as a prebiotic, feeding the “good” bacteria in our bodies. Arabinoxylan oligosaccharide is a prebiotic carbohydrate derived from wheat bran that has been shown to stimulate the activity of bifidobacteria in the colon. These bacteria are normally found in a healthy human gut. Changes in their amount or activity have been associated with gastrointestinal diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, and irritable bowel syndrome 13, 14.

Gluten Containing Foods

1)Wheat is commonly found in:

- breads

- baked goods

- soups

- pasta

- cereals

- sauces

- salad dressings

- roux

Varieties and derivatives of wheat such as:

- wheatberries

- durum

- emmer

- semolina

- spelt

- farina

- farro

- graham

- KAMUT® khorasan wheat

- einkorn wheat

2) Barley is commonly found in:

- malt (malted barley flour, malted milk and milkshakes, malt extract, malt syrup, malt flavoring, malt vinegar)

- food coloring

- soups

- beer

- Brewer’s Yeast

3) Rye is commonly found in:rye

- rye bread, such as pumpernickel

- rye beer

- cereals

4) Triticale is a newer grain, specifically grown to have a similar quality as wheat, while being tolerant to a variety of growing conditions like rye. It can potentially be found in:

- breads

- pasta

- cereals

5) Malt in various forms including: malted barley flour, malted milk or milkshakes, malt extract, malt syrup, malt flavoring, malt vinegar

6) Brewer’s Yeast

7) Wheat Starch that has not been processed to remove the presence of gluten to below 20ppm and adhere to the FDA Labeling Law. According to the FDA, if a food contains wheat starch, it may only be labeled gluten-free if that product has been processed to remove gluten, and tests to below 20 parts per million of gluten. With the enactment of this law on August 5th, 2014, individuals with celiac disease or gluten intolerance can be assured that a food containing wheat starch and labeled gluten-free contains no more than 20ppm of gluten. If a product labeled gluten-free contains wheat starch in the ingredient list, it must be followed by an asterisk explaining that the wheat has been processed sufficiently to adhere to the FDA requirements for gluten-free labeling.

Common Foods That Contain Gluten

- Pastas: raviolis, dumplings, couscous, and gnocchi

- Noodles: ramen, udon, soba (those made with only a percentage of buckwheat flour) chow mein, and egg noodles. (Note: rice noodles and mung bean noodles are gluten free)

- Breads and Pastries: croissants, pita, naan, bagels, flatbreads, cornbread, potato bread, muffins, donuts, rolls

- Crackers: pretzels, goldfish, graham crackers

- Baked Goods: cakes, cookies, pie crusts, brownies

- Cereal & Granola: corn flakes and rice puffs often contain malt extract/flavoring, granola often made with regular oats, not gluten-free oats

- Breakfast Foods: pancakes, waffles, french toast, crepes, and biscuits.

- Breading & Coating Mixes: panko breadcrumbs

- Croutons: stuffings, dressings

- Sauces & Gravies (many use wheat flour as a thickener): traditional soy sauce, cream sauces made with a roux

- Flour tortillas

- Beer (unless explicitly gluten-free) and any malt beverages (see “Distilled Beverages and Vinegars” below for more information on alcoholic beverages)

- Brewer’s Yeast

- Anything else that uses “wheat flour” as an ingredient

Distilled Beverages And Vinegars

Most distilled alcoholic beverages and vinegars are gluten-free. These distilled products do not contain any harmful gluten peptides even if they are made from gluten-containing grains. Research indicates that the gluten peptide is too large to carry over in the distillation process, leaving the resulting liquid gluten-free.

Wines and hard liquor/distilled beverages are gluten-free. However, beers, ales, lagers, malt beverages and malt vinegars that are made from gluten-containing grains are not distilled and therefore are not gluten-free. There are several brands of gluten-free beers available in the United States and abroad.

Foods That May Contain Gluten

- Energy bars/granola bars – some bars may contain wheat as an ingredient, and most use oats that are not gluten-free

- French fries – be careful of batter containing wheat flour or cross-contact from fryers

- Potato chips – some potato chip seasonings may contain malt vinegar or wheat starch

- Processed lunch meats

- Candy and candy bars

- Soup – pay special attention to cream-based soups, which have flour as a thickener. Many soups also contain barley

- Multi-grain or “artisan” tortilla chips or tortillas that are not entirely corn-based may contain a wheat-based ingredient

- Salad dressings and marinades – may contain malt vinegar, soy sauce, flour

- Starch or dextrin if found on a meat or poultry product could be from any grain, including wheat

- Brown rice syrup – may be made with barley enzymes

- Meat substitutes made with seitan (wheat gluten) such as vegetarian burgers, vegetarian sausage, imitation bacon, imitation seafood (Note: tofu is gluten-free, but be cautious of soy sauce marinades and cross-contact when eating out, especially when the tofu is fried)

- Soy sauce (though tamari made without wheat is gluten-free)

- Self-basting poultry

- Pre-seasoned meats

- Cheesecake filling – some recipes include wheat flour

- Eggs served at restaurants – some restaurants put pancake batter in their scrambled eggs and omelets, but on their own, eggs are naturally gluten-free

Other Items That Must Be Verified By Reading The Label Or Checking With The Manufacturer

- Lipstick, lipgloss, and lip balm because they are unintentionally ingested

- Communion wafers

- Herbal or nutritional supplements

- Drugs and over-the-counter medications (Learn about Gluten in Medication)

- Vitamins and supplements (Learn about Vitamins and Supplements)

- Play-dough: children may touch their mouths or eat after handling wheat-based play-dough. For a safer alternative, make homemade play-dough with gluten-free flour.

Gluten in Medication

The true chances of getting a medication that contains gluten is extremely small, but you should still eliminate all risks by evaluating the ingredients in your medications by reading the medicine labels 15.

Medications are composed of many ingredients, both inside and outside of the product. These ingredients, also known as excipients, include the active component, absorbents (which absorb water to allow the tablet to swell and disintegrate), protectants, binders, coloring agents, lubricators, and bulking agents (which allow some products to dissolve slowly as they travel throughout the intestinal tract). Excipients can be synthetic or from natural sources that are derived from either plants or animals. Excipients are considered inactive and safe for human use by the FDA, but can be a potential source for unwanted reactions.

- Dr. Steve Plogsted (Associate Clinical Professor of Pharmacy, Ohio Northern University College of Pharmacy) maintains a website that provides information regarding gluten-free drugs 16. However, this site is for informational purposes only and may contain inaccuracies. Dr. Plogsted advises that, “All persons should interpret the information with caution and should seek medical advice when necessary.” 16

Vitamins & Supplements

Vitamin and mineral therapy can be used in addition to the standard gluten-free diet to hasten a patient’s recovery from nutritional deficiency. However, certain ingredients in vitamins and supplements – typically the inactive ingredients – can contain gluten, so extra care must be taken to avoid any gluten exposure 17.

People recently diagnosed with celiac disease are commonly deficient in fiber, iron, calcium, magnesium, zinc, folate, niacin, riboflavin, vitamin B12, and vitamin D, as well as in calories and protein. Deficiencies in copper and vitamin B6 are also possible, but less common. A study from 2002 by Bona et. al. indicated that the delay in puberty in children with celiac disease may partially be due to low amounts of B vitamins, iron, and folate.

However, after treatment with a strict gluten-free diet, most patients’ small intestines recover and are able to properly absorb nutrients again, and therefore do not require supplementation. For certain patients however, nutrient supplements may be beneficial.

It is also important to remember that “wheat-free” does not necessarily mean “gluten-free.” Be wary, as many products may appear to be gluten-free, but are not.

If In Doubt, Go Without !

When unable to verify ingredients for a food item or if the ingredient list is unavailable DO NOT EAT IT. Adopting a strict gluten-free diet is the only known treatment for those with gluten-related disorders.

Gluten Free Foods

The most cost-effective and healthy way to follow the gluten-free diet is to seek out these naturally gluten-free food groups, which include:

- Fruits

- Vegetables

- Meat and poultry

- Fish and seafood

- Dairy

- Eggs

- Beans, legumes, and nuts

- Gluten free grains e.g. rice, sorghum, millet and corn

There are many naturally gluten-free grains that you can enjoy in a variety of creative ways. Many of these grains can be found in your local grocery store, but some of the lesser-known grains may only be found in specialty or health food stores. It is not recommended to purchase grains from bulk bins because of the possibility for cross-contact with gluten.

The following grains and other starch-containing foods are naturally gluten-free:

- Rice

- Cassava

- Corn (maize)

- Soy

- Potato

- Tapioca

- Beans

- Sorghum

- Quinoa

- Millet

- Buckwheat groats (also known as kasha)

- Arrowroot

- Amaranth

- Teff

- Flax

- Chia

- Yucca

- Gluten-free oats

- Nut flours

There has been some research that some naturally gluten-free grains may contain gluten from cross-contact with gluten-containing grains through harvesting and processing. If you are concerned about the safety of a grain, purchase only versions that are tested for the presence of gluten and contain less than 20 ppm.

Is a gluten-free diet safe if you don’t have celiac disease ?

In recent years, more people without celiac disease have adopted a gluten-free diet, believing that avoiding gluten is healthier or could help them lose weight. No current data suggests that the general public should maintain a gluten-free diet for weight loss or better health 18, 19.

A gluten-free diet isn’t always a healthy diet. For instance, a gluten-free diet may not provide enough of the nutrients, vitamins, and minerals the body needs, such as fiber, iron, and calcium. Some gluten-free products can be high in calories and sugar.

The composition of the gut microbiota is susceptible to the influence of the diet and, especially, to the quality and quantity of ingested carbohydrates 20, 21, 22. The reductions in polysaccharide intake associated with the gluten-free diet could explain the observed changes in the microbiota, since these dietary compounds usually reach the distal part of the colon partially undigested, and constitute one of the main energy sources for commensal components of the gut microbiota 23. The genome of these bacteria encodes many enzymes specialized in the utilization of non-digestible carbohydrates, which provide these bacterial groups a competitive advantage over potentially pathogenic bacteria to colonize the intestine 24, 25.

It also seems feasible that when the growth of beneficial bacteria is not supported due to a reduced supply of their main energy sources other bacterial groups, which can be opportunistic pathogens, can overgrowth leading to intestinal dysbiosis. Within the gut ecosystem, the microbiota acts as a metabolic organ whose survival and composition is determined by a dynamic process of selection and competition. In fact, intake of complex dietary carbohydrates (e.g., dietary fiber) has been shown to influence both microbial colonization and fermentation variables in the mammalian gut. Thus, high intake of dietary fiber resulted in a greater short-chain fatty acid concentration in (e.g., acetic and butyric acids), and lower Escherichia coli counts in piglet intestine, while an opposite trend was shown with low fiber intake 26.

In a small study 27 involving 10 healthy subjects (30.3 years-old), who were following a gluten-free diet over one month by replacing the gluten-containing foods they usually ate with certified gluten-free foods (with no more than 20 parts per million of gluten). Analyses of their fecal microbiota and dietary intakes, indicated that populations of generally regarded healthy bacteria decreased (Bifidobacterium, B. longum and Lactobacillus), while populations of potentially unhealthy bacteria increased parallel to reductions in the intake of polysaccharides (from 117 g to 63 g on average) after following the gluten-free diet. In particular, increases were detected in numbers of E. coli and total Enterobacteriaceae, which may include opportunistic pathogens 28. Although this preliminary study has limitations, including number of participants and the short duration of the intervention, the changes in the microbiota found in healthy subjects following a gluten-free diet, in particular the reductions in Bifidobacterium plus Lactobacillus populations relative to Gram-negative bacteria (Bacteroides and E. coli) were detected. These findings indicate that gluten-free diet may contribute to reducing beneficial bacterial counts and increasing enterobacterial counts, which are microbial features associated with the disease 29, 30 and, therefore, it would not favor completely the normalization of the gut ecosystem 27. This evidence suggests a disruption of the delicate balance between the host and its intestinal microbiota (dysbiosis), which might favor the overgrowth of opportunistic pathogens and weaken the host defences against infection and chronic inflammation via possible alterations in mucosal immunity 31.

If you think you might have celiac disease, don’t start avoiding gluten without first speaking with your doctor. If your doctor diagnoses you with celiac disease, he or she will put you on a gluten-free diet.

When Gluten Is a Problem

What’s not great about gluten is that it can cause serious side effects in certain individuals. Some people react differently to gluten, where the body senses it as a toxin, causing one’s immune cells to overreact and attack it. If an unknowingly sensitive person continues to eat gluten, this creates a kind of battle ground resulting in inflammation. The side effects can range from mild (fatigue, bloating, alternating constipation and diarrhea) to severe (unintentional weight loss, malnutrition, intestinal damage) as seen in the autoimmune disorder celiac disease. Estimates suggest that 1 in 133 Americans has celiac disease, or about 1% of the population, but about 83% of them are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed with other conditions 32, 33. Research shows that people with celiac disease also have a slightly higher risk of osteoporosis and anemia (due to malabsorption of calcium and iron, respectively); infertility; nerve disorders; and in rare cases cancer 34. The good news is that removing gluten from the diet may reverse the damage. A gluten-free diet is the primary medical treatment for celiac disease. However, understanding and following a strict gluten-free diet can be challenging, possibly requiring the guidance of a registered dietitian to learn which foods contain gluten and to ensure that adequate nutrients are obtained from gluten-free alternatives. Other conditions that may require the reduction or elimination of gluten in the diet include:

- Non-celiac gluten sensitivity, also referred to as gluten sensitive enteropathy or gluten intolerance—An intolerance to gluten with similar symptoms as seen with celiac disease, but without the accompanying elevated levels of antibodies and intestinal damage. There is not a diagnostic test for GSE but is determined by persistent symptoms and a negative diagnostic celiac test.

- Wheat allergy—An allergy to one or more of the proteins (albumin, gluten, gliadin, globulin) found in wheat, diagnosed with positive immunoglobulin E blood tests and a food challenge. Compare this with celiac disease, which is a single intolerance to gluten. Symptoms range from mild to severe and may include swelling or itching of the mouth or throat, hives, itchy eyes, shortness of breath, nausea, diarrhea, cramps, and anaphylaxis. People who test negative for this condition may still have gluten sensitivity. This condition is most often seen in children, which most outgrow by adulthood.

- Dermatitis herpetiformis—A skin rash that results from eating gluten. It is an autoimmune response that exhibits itself as a persistent red itchy skin rash that may produce blisters and bumps. Although people with celiac disease may have dermatitis herpetiformis, the reverse is not always true. Those with dermatitis herpetiformisoften do not have any digestive symptoms.

It is important to note that gluten is a problem only for those who react negatively to it. Most people can and have eaten gluten most of their lives, without any adverse side effects.

Gluten Related Disorders

Gluten-related disorders have gradually emerged as an epidemiologically relevant phenomenon with an estimated global prevalence around 5%. Celiac disease, wheat allergy and non-celiac gluten sensitivity represent different gluten-related disorders 35.

There are a number of definitions in use to define gluten related disorders. By and large, all of them encompass the same basic principles. For the purpose of this report, the following definitions have been chosen for these conditions – celiac disease, wheat allergy and Gluten Sensitivity (Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity).

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease (also known as coeliac disease, celiac sprue, non-tropical sprue, autoimmune enteropathy and gluten sensitive enteropathy) is an immune-mediated systemic disorder triggered by gluten and related prolamins present in wheat, barley, and rye that occur in genetically susceptible individuals who have the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8 haplotypes. It is characterized by an inflammatory enteropathy with variable degrees of severity, a wide range of gastrointestinal and/or systemic complaints, and the presence of celiac-specific autoantibodies 36.

Celiac disease is triggered by eating foods containing gluten. Gluten is a protein found naturally in wheat, barley, and rye, and is common in foods such as bread, pasta, cookies, and cakes. Many pre-packaged foods, lip balms and lipsticks, hair and skin products, toothpastes, vitamin and nutrient supplements, and, rarely, medicines, contain gluten.

For more information about celiac disease see the post on What is celiac disease ?

When people with celiac disease eat gluten (a protein found in wheat, rye and barley), their body mounts an immune response that attacks the small intestine. These attacks lead to damage on the villi, small fingerlike projections that line the small intestine, that promote nutrient absorption. When the villi get damaged, nutrients cannot be absorbed properly into the body 37.

It is estimated to affect 1 -3 in 100 (1-3%) people worldwide, except for populations in which the HLA risk alleles (celiac disease genes) (HLA-DQ2 and/or DQ8) are rare such as in South East Asia 38, 39, 40, 41. Two and one-half million Americans are undiagnosed and are at risk for long-term health complications 37.

Celiac disease is also hereditary, meaning that it runs in families. People with a first-degree relative with celiac disease (parent, child, sibling) have a 1 in 10 risk of developing celiac disease 37. Furthermore, first-degree family members (parent, child, sibling) of patients with celiac disease have an increased risk for the disease, already at a young age, ranging from 5% to 30%, depending on their sex and HLA makeup 42, 43.

Celiac disease is different from gluten sensitivity or wheat allergy 44. If you have gluten sensitivity, you may have symptoms similar to those of celiac disease, such as abdominal pain and tiredness. Unlike celiac disease, gluten sensitivity does not damage the small intestine.

Wheat Allergy

Wheat allergy is a hypersensitivity reaction to wheat proteins mediated through immune mechanisms and involving mast cell activation. The immune response can be immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated, non-IgE mediated, or a combination of both. Wheat allergy is most commonly a food allergy, but wheat can become a sensitizer when the exposure occurs through the skin or airways (baker’s asthma) 45, 18, 46.

In both wheat allergy and celiac disease, your body’s immune system reacts to wheat. However, some symptoms in wheat allergies, such as having itchy eyes or a hard time breathing, are different from celiac disease. Wheat allergy is an immunoglobulin E–mediated reaction to the insoluble gliadins, particularly ω-5 gliadin, the major allergen of wheat-dependent, exercise-induced anaphylaxis (“baker’s asthma”) 47. Usually, patients with wheat allergy are not allergic to other prolamines containing grains, such as rye or barley and their wheat-free diet is less restrictive than the strict gluten-free diet for patients with celiac disease. The symptoms of wheat allergy develop within minutes to hours after gluten ingestion and are typical for an immunoglobulin E–mediated allergy, including itching and swelling in the mouth, nose, eyes, and throat; rash and wheezing; and life-threatening anaphylaxis. The gastrointestinal manifestations of wheat allergy may be similar to those of coeliac disease, but wheat allergy does not cause (permanent) gastrointestinal damage 18. Those with wheat allergy also benefit from the gluten free diet, although these patients often do not need to restrict rye, barley, and oats from their diet 18.

Table 1. The clinical manifestations of gluten-related disorders are numerous and complex in nature and involve multiple organ systems. There is considerable overlap of symptoms between these conditions, which makes differentiation impossible on clinical grounds alone. (Source 48).

What is Gluten Sensitivity (Gluten Intolerance) or Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Gluten sensitivity is also known as non-celiac gluten sensitivity, is a clinical condition in which intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms are triggered by gluten ingestion, in the absence of celiac disease and wheat allergy 7. The symptoms usually occur soon after gluten ingestion, improving or disappearing within hours or a few days after gluten withdrawal and relapsing following its reintroduction 49. Ataxia and peripheral neuropathy are the most common neurological manifestations of gluten sensitivity. Myopathy is a less common and poorly characterized additional neurological manifestation of gluten sensitivity 50.

The prevalence of gluten sensitivity in the general population is unknown, but it has been estimated to be anywhere between 0.5% and 6% in different countries. No data on prevalence are available for the paediatric population, and the scarce data on children refer to gluten avoidance and not to Gluten sensitivity per se 51, 52. The disorder seems to be more common in girls and in young/middle-aged adults 51, 53.

Gluten sensitivity is a controversial subject, where patients who have neither celiac disease nor wheat allergy, have varying degrees of symptomatic improvement on the gluten free diet. Conditions in this category include dermatitis herpetiformis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and neurologic diseases such as gluten-sensitive ataxia and autism 18, 53, 54. In children, gluten sensitivity tends to manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain and chronic diarrhoea, whereas the systemic manifestations seem to be less frequent, the most common systemic symptom being tiredness 55. Unlike patients with coeliac disease, patients with gluten sensitivity do not appear to be at a higher risk for long-term complications such as nutrient deficiencies secondary to malabsorption. Patients with gluten sensitivity do not seem to have autoimmune comorbidities, as observed in coeliac disease, but allergy is more frequently seen in patients with gluten sensitivity 51, 53.

An association between gluten sensitivity and neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders, has been suggested 56, 57. The conclusion of a Cochrane review including 2 small randomized controlled trials, however, is that there is no evidence for efficacy of gluten exclusion in these disorders 53, 58. The major effect of gluten in patients with gluten sensitivity is in the perception of their general well-being 59.

How is Gluten Sensitivity Diagnosed

The diagnosis of gluten sensitivity is based on exclusion of other gluten-related disorders, especially celiac disease and wheat allergy. Unfortunately, there are no biological markers specific to gluten sensitivity. The only antibodies observed in a retrospective study of adults with gluten sensitivity are immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin A anti-gliadin antibodies (AGAs), which occur in, respectively, 56% and 8% of the patients compared with 80% and 75% in the population with celiac disease 60. It, however, has to be taken into account that anti-gliadin antibodies are also frequently present in the general population. The vast majority of patients with gluten sensitivity showed immunoglobulin G anti-gliadin antibodies disappearance after gluten withdrawal. Half of the patients with gluten sensitivity were HLA-DQ2 or -DQ8 positive, a prevalence only slightly higher than in the general population (30%–40%) 49, 53. A double-blind, placebo-controlled challenge has been suggested to confirm gluten sensitivity diagnosis. This is a complicated procedure to be performed in practice, given the difficulty in preparing the intervention products, the need for highly trained personnel, and high costs 61. An alternative is the open food challenge, but this is less reliable because of the important placebo effect. It is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of gluten sensitivity on a gluten-containing diet to avoid missing the diagnosis of true coeliac disease 62.

What Causes Gluten Sensitivity ?

The cause of gluten sensitivity is unknown. There is agreement among researchers that only minor histological alterations have been found in the small bowel mucosa of patients with gluten sensitivity, compatible with 0 (normal mucosa) or I (mild alterations) in Marsh classifications 51, 54, 63. On the contrary, there is discrepancy regarding intestinal permeability in gluten sensitivity, because some studies have reported normal permeability and others not, with increased permeability in a subgroup of HLA-DQ2/DQ8–positive patients 54, (Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013; 144:903–911.()), 64.

Furthermore, gene expression analyses showed increased expression of Toll-like receptor 2 and reduced expression of the T-regulatory cell marker forkhead box P3 in patients with gluten sensitivity compared with those in patients with celiac disease, suggesting a role of innate immunity in the pathogenesis of gluten sensitivity. Contrary to coeliac disease, however, most studies show that adaptive immunity markers are not increased in patients with gluten sensitivity 64, 65.

Gluten Sensitivity Treatment

In general, gluten sensitivity, and celiac disease and wheat allergy, is treated with a gluten-free diet, but, considering the lack of knowledge about its gluten- (dose-)related character and about the permanent or transient nature of the condition, periodic reintroduction of gluten into the diet may be advised 49, 66.

Summary

Gluten free diet is a diet that is critical in treating celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy. Gluten is a protein found naturally in wheat, barley, and rye that triggers an immune reaction if you have celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy.

If you are concerned about celiac disease, you are strongly discouraged from starting a gluten-free diet without having had a firm diagnosis by your medical doctor. And if you change your diet to the gluten free diet, even for as little as a month, can complicate the diagnostic process. This is because all celiac disease blood tests require that you be on a gluten-containing diet to be accurate.

Celiac disease and wheat allergy are two well-described gluten-related diseases with clear guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Gluten sensitivity is a controversial entity with more questions than answers concerning its nature, diagnosis, and treatment 7. Researchers are still learning more about gluten sensitivity. If your health care provider thinks you have it, he or she may suggest that you stop eating gluten to see if your symptoms go away. However, you should first be tested to rule out celiac disease.

References- Topper A. Non-celiacs Drive Gluten-Free Market Growth. Mintel Group Ltd. Web. http://www.mintel.com/blog/food-market-news/gluten-free-consumption-trends. Accessed Mar 27, 2017. http://www.mintel.com/blog/food-market-news/gluten-free-consumption-trends

- Reilly, N.R. The Gluten-Free Diet: Recognizing Fact, Fiction, and Fad. The Journal of Pediatrics. Volume 175, August 2016, pages 206–210.

- Tortora, R., et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Feb;41(4):352-9.

- Kabbani, T.A., et al. Body mass index and the risk of obesity in coeliac disease treated with the gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Mar;35(6):723-9.

- Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council. Gluten in Grains. http://www.glnc.org.au/grains-2/allergies-intolerances-to-grains/gluten-in-grains/

- The Royal Society, published online 25 February 2002. The structure and properties of gluten:an elastic protein from wheat grain. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1692935/pdf/11911770.pdf

- Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition: April 2015 – Volume 60 – Issue 4 – p 429–432. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000708. Coeliac Disease and Noncoeliac Gluten Sensitivity. http://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2015/04000/Coeliac_Disease_and_Noncoeliac_Gluten_Sensitivity.7.aspx

- Lebwohl B, Cao Y, Zong G, Hu FB, Green PHR, Neugut AI, Rimm EB, Sampson L, Dougherty L, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Sun Q, Chan AT. Long term gluten consumption in adults without celiac disease and risk of coronary heart disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017 May 2;357:j1892.

- Liu S, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, et al. Whole-grain consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:412-9.

- Mellen PB, Walsh TF, Herrington DM. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:283-90.

- de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e261.

- Johnsen, N.F., et al. Whole-grain products and whole-grain types are associated with lower all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the Scandinavian HELGA cohort. British Journal of Nutrition, 114(4), 608-23.

- Neyrinck, A.M., et al. Wheat-derived arabinoxylan oligosaccharides with prebiotic effect increase satietogenic gut peptides and reduce metabolic endotoxemia in diet-induced obese mice. Nutr Diabetes. 2012 Jan; 2(1): e28.

- Tojo, R., et al. Intestinal microbiota in health and disease: role of bifidobacteria in gut homeostasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov 7;20(41):15163-76.

- Celiac Disease Foundation. Gluten in Medication. https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/gluten-medication/

- Gluten Free Drugs. http://www.glutenfreedrugs.com/

- Celiac Disease Foundation. Vitamins & Supplements. https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/vitamins-and-supplements/

- Pietzak, M. Celiac Disease, Wheat Allergy, and Gluten Sensitivity: When Gluten Free Is Not a Fad. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;36:68S-75S.

- Marcason, W. Is there evidence to support the claim that a gluten-free diet should be used for weight loss? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2011;111(11):1796.

- Duncan SH, Belenguer A, Holtrop G, Johnstone AM, Flint HJ, Lobley GE. Reduced dietary intake of carbohydrates by obese subjects results in decreased concentrations of butyrate and butyrate-producing bacteria in feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1073–1078. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1828662/

- Flint HJ, Bayer EA, Rincon MT, Lamed R, White BA. Polysaccharide utilization by gut bacteria: potential for new insights from genomic analysis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:121–131. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18180751

- Barboza M, Sela DA, Pirim C, Locascio RG, Freeman SL, German JB, et al. Glycoprofiling bifidobacterial consumption of galacto-oligosaccharides by mass spectrometry reveals strain specific, preferential consumption of glycans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7319–7325. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2786398/

- De Graaf AA, Venema K. Gaining insight into microbial physiology in the large intestine: a special role for stable isotopes. Adv Microb Physiol. 2008;53:73–168. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17707144

- Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:776–788. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2664199/

- Schell MA, Karmirantzou M, Snel B, Vilanova D, Berger B, Pessi G, et al. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14422–14427. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC137899/

- Hermes RG, Molist F, Ywazaki M, Nofrarías M, Gomez de Segura A, Gasa J, et al. Effect of dietary level of protein and fiber on the productive performance and health status of piglets. J Anim Sci. 2009;87:3569–3577. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19648494

- Gut Microbes. 2010 May-Jun; 1(3): 135–137. Published online 2010 Mar 16. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.11868. Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult humans. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3023594/

- Hurrell E, Kucerova E, Loughlin M, Caubilla-Barron J, Hilton A, Armstrong R, et al. Neonatal enteral feeding tubes as loci for colonisation by members of the Enterobacteriaceae. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;1:146. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2749046/

- Nadal I, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M, Sanz Y. Imbalance in the composition of the duodenal microbiota of children with coeliac disease. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1669–1674. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18033837

- Collado MC, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M, Sanz Y. Specific duodenal and faecal bacterial groups associated with paediatric coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:264–269. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18996905

- Collins SM, Denou E, Verdu EF, Bercik P. The putative role of the intestinal microbiota in the irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;27:85–89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19740713

- Beyond Celiac. Celiac Disease: Fast Facts https://www.beyondceliac.org/celiac-disease/facts-and-figures. https://www.beyondceliac.org/celiac-disease/facts-and-figures/

- Riddle, M.S., Murray, J.A., Porter, C.K. The Incidence and Risk of Celiac Disease in a Healthy US Adult Population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(8):1248-1255.

- N., Freeman, H.J., Thomson, A.B.R. Celiac disease: Prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Nov 14; 18(42): 6036–6059.

- World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Jun 21;21(23):7110-9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7110. Diagnosis of gluten related disorders: Celiac disease, wheat allergy and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26109797

- Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR, et al European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 54:136–160. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22197856

- Celiac Disease Foundation. What is Celiac Disease ? https://celiac.org/celiac-disease/understanding-celiac-disease-2/what-is-celiac-disease/

- Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med 2010; 42:587–595.

- Myléus A, Ivarsson A, Webb C, et al. Celiac disease revealed in 3% of Swedish 12-year-olds born during an epidemic. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009; 49:170–176.

- Catassi C, Gatti S, Fasano A. The new epidemiology of celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014; 59 (suppl 1):S7–S9.

- Ivarsson A, Myleus A, Norstrom F, et al. Prevalence of childhood celiac disease and changes in infant feeding. Pediatrics 2013; 131:e687–e694.

- Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 54:136–160.

- Vriezinga SL, Auricchio R, Bravi E, et al. Randomized feeding intervention in infants at high risk for celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1304–1315.

- The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Health Information Center. Celiac Disease. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/celiac-disease/all-content

- Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition: July 2016 – Volume 63 – Issue 1 – p 156–165. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001216. NASPGHAN Clinical Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gluten-related Disorders. http://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2016/07000/NASPGHAN_Clinical_Report_on_the_Diagnosis_and.28.aspx

- Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition: April 2015 – Volume 60 – Issue 4 – p 429–432. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000708. Coeliac Disease and Noncoeliac Gluten Sensitivity. http://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2015/04000/Coeliac_Disease_and_Noncoeliac_Gluten_Sensitivity.7.aspx

- Mulder CJ, van Wanrooij RL, Bakker SF, et al. Gluten-free diet in gluten-related disorders. Dig Dis 2013; 31:57–62.

- Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 63(1):156-165, July 2016. NASPGHAN Clinical Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gluten-related Disorders. http://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2016/07000/NASPGHAN_Clinical_Report_on_the_Diagnosis_and.28.aspx

- Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med 2012; 10:3.

- Muscle Nerve. 2007 Apr;35(4):443-50. Myopathy associated with gluten sensitivity. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17143894?dopt=Abstract

- Volta U, Bardella MT, Calabro A, et al. An Italian prospective multicenter survey on patients suspected of having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Med 2014; 12:85.

- Tanpowpong P, Ingham TR, Lampshire PK, et al. Coeliac disease and gluten avoidance in New Zealand children. Arch Dis Child 2012; 97:12–16.

- Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, et al. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients 2013; 5:3839–3853.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:508–514.

- Francavilla R, Cristofori F, Castellaneta S, et al. Clinical, serologic, and histologic features of gluten sensitivity in children. J Pediatr 2014; 164:463–467.

- Batista IC, Gandolfi L, Nobrega YK, et al. Autism spectrum disorder and celiac disease: no evidence for a link. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012; 70:28–33.

- Whiteley P, Haracopos D, Knivsberg AM, et al. The ScanBrit randomised, controlled, single-blind study of a gluten- and casein-free dietary intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutr Neurosci 2010; 13:87–100.

- Millward C, Ferriter M, Calver S, et al. Gluten- and casein-free diets for autistic spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 2:CD003498.

- Peters SL, Biesiekierski JR, Yelland GW, et al. Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity—an exploratory clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39:1104–1112.

- Volta U, Tovoli F, Cicola R, et al. Serological tests in gluten sensitivity (nonceliac gluten intolerance). J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46:680–685.

- Lundin KE, Alaedini A. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2012; 22:723–734.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Shepherd SJ, et al. Characterization of adults with a self-diagnosis of nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Nutr Clin Pract 2014; 29:504–509.

- Sapone A, Lammers KM, Mazzarella G, et al. Differential mucosal IL-17 expression in two gliadin-induced disorders: gluten sensitivity and the autoimmune enteropathy celiac disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010; 152:75–80.

- Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V, et al. Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Med 2011; 9:23.

- Brottveit M, Beitnes AC, Tollefsen S, et al. Mucosal cytokine response after short-term gluten challenge in celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:842–850.

- Volta U, De GR. New understanding of gluten sensitivity. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 9:295–299.