What is hallux valgus

Hallux valgus is also called bunion or hallux abducto valgus, is a structural foot deformity in which the angular deviation of the hallux (big toe) is greater than 15 degrees toward the lesser toes with respect to the first metatarsal bone, and it appears as a medial bony enlargement of the first metatarsal head 1. Hallux valgus or bunion forms when your big toe points toward the second toe. This causes a bump to appear on the inside edge of your toe. The valgus position of the great toe is not the only deformity. In the majority of cases the metatarsus is splayed, increasing the prominence of the metatarsophalangeal joint. Moreover, the great toe is often somewhat pronated, so that the nail faces medially.

Hallux valgus is the commonest forefoot deformity, with an estimated prevalence of 23% to 35% 1. A recent review estimates the global prevalence of hallux valgus at up to 23% in 18- to 65-year-olds and 35% in those over 65.

Hallux valgus starts out small — but it usually gets worse over time (especially if the individual continues to wear tight, narrow shoes). Extra bone and a fluid-filled sac grow at the base of the big toe. Because the metatarsophalangeal joint flexes with every step, the bigger the hallux valgus bunion gets, the more painful and difficult walking can become.

An advanced hallux valgus can greatly alter the appearance of the foot. In severe hallux valgus, the big toe may angle all the way under or over the second toe. Pressure from the big toe may force the second toe out of alignment, causing it to come in contact with the third toe. Calluses may develop where the toes rub against each other, causing additional discomfort and difficulty walking.

Hallux valgus causes symptoms in three particular ways. First and foremost is pain in the bunion, the pressure-sensitive prominence on the medial side of the head of the first metatarsal. It hurts to wear a shoe. Furthermore, the valgus deviation of the great toe often results in a lack of space for the other toes. They become displaced, usually upwards, leading to pressure against the shoe. This is termed hammer toe or claw toe. Finally, normal function of the forefoot relies heavily on the great toe pressing down on the ground during gait. Since the valgus deformity stops this happening to a sufficient degree, metatarsal heads of 2–5 toes are overloaded. The resulting pain is referred to as transfer metatarsalgia.

Non-operative hallux valgus treatment may alleviate symptoms but does not correct the deformity of the big toe. Hallux valgus surgery is indicated if the pain persists. The correct operation must be selected from a wide variety of available techniques.

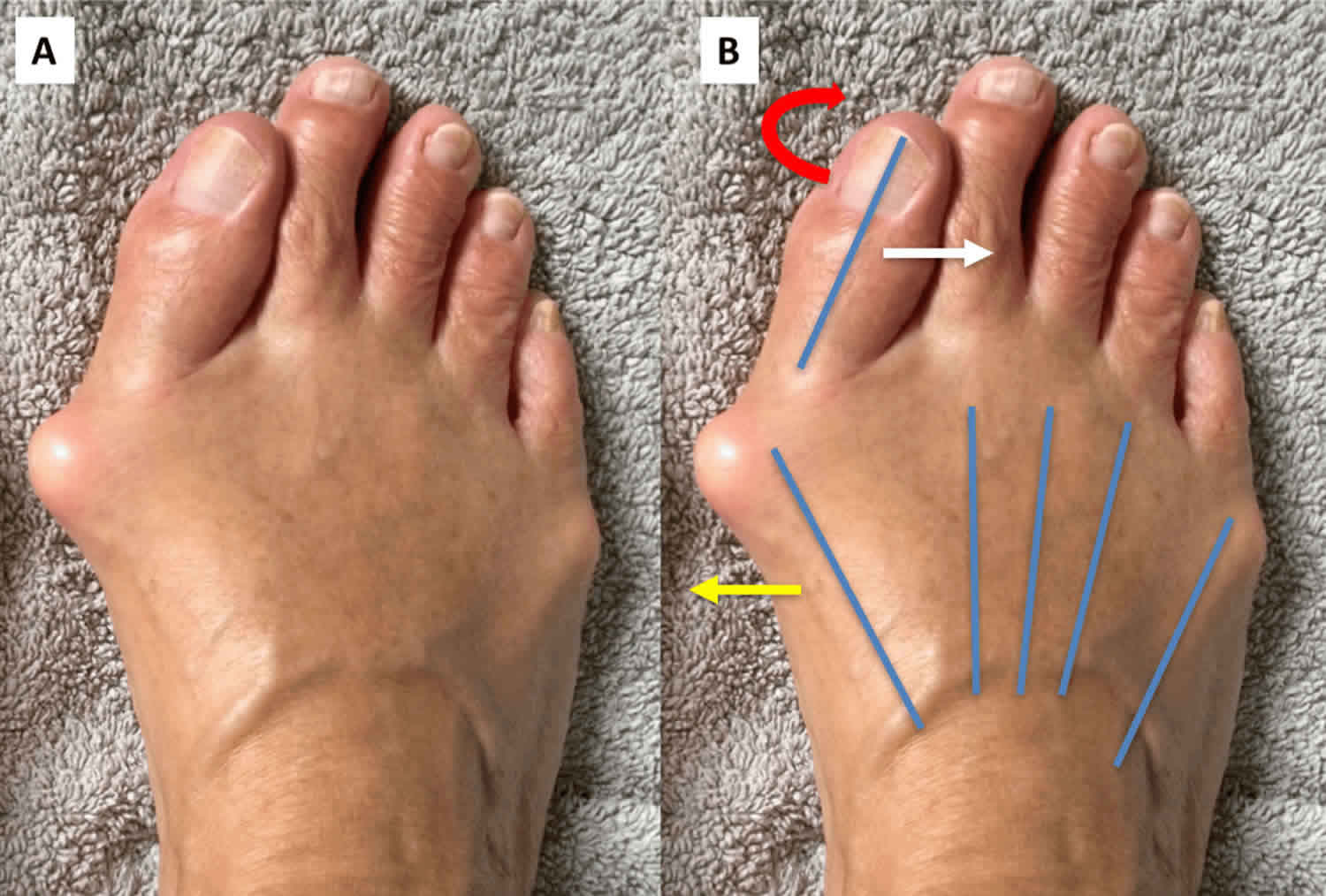

Figure 1. Hallux valgus

Figure 2. Hallux valgus bunion

Mild hallux valgus

Mild hallux valgus deformities are found predominantly in young women (Figure 3a). The patients complain principally of pressure pain in the bunion, which is moderately prominent. The deformity is flexible, i.e., the hallux can be restored to the normal position manually, without any significant resistance. Moreover, the metatarsus is only slightly splayed, so that the intermetatarsal angle is less than 15 degrees on a weight bearing radiograph. The mobility of the first metatarsophalangeal joint is not restricted, and no osteoarthritis is seen on the radiograph. Mild deformities can be effectively treated by distal metatarsal I osteotomies, e.g., chevron osteotomy (Figure 3b). This intervention, initially known as Austin osteotomy, was first described in 1962 2. A V-shaped cut is made in the head of metatarsal 1 and the bone is displaced laterally by one third to a half of its width, thus correcting the intermetatarsal angle. In addition, the exostosis on the medial aspect of the head of metatarsal 1 is shaved off and the capsule tightened so that by the end of the operation the great toe is in the proper position. Fixation with a small implant is necessary to prevent reposition loss, but an inexpensive small-fragment screw or a wire will suffice. There is no consensus on the advisability of carrying out additional lateral release in the case of an incongruent metatarsophalangeal joint. Lateral release is unnecessary in mild deformities, and other procedures are available for more severe cases of hallux valgus 3; lateral release increases the risk of poor perfusion of the head of metatarsal 1 with consequent necrosis 4. Postoperatively the toe must be held straight for 6 weeks with a corrective bandage. During this time the patient has to wear a flat-soled healing shoe that allows full weight bearing.

Figure 3. Mild hallux valgus

Footnote: Radiographs of a foot with mild hallux valgus

(a) Mild malposition with an intermetatarsal angle of 13°, a congruent metatarsophalangeal joint, and a flexible deformity

(b) After correction by Chevron osteotomy: the head of metatarsal I was shifted 5 mm to lateral and the capsule on the medial side of the first metatarsophalangeal joint was tightened

[Source 1 ]Severe hallux valgus deformities

Severe hallux valgus deformities mostly affect the middle-aged and elderly, predominantly women (Figure 4a) 3. The great toe can no longer be fully repositioned manually, and on radiographs the joint is seen to be incongruent, i.e. the proximal phalanx is subluxated laterally on the head of metatarsal I. The metatarsus is distinctly splayed, further increasing the prominence of the bunion on the medial aspect of the head of metatarsal I. The intermetatarsal angle is 15° or more on weight bearing radiographs (3). In this case the soft tissues lateral to the first metatarsophalangeal joint must be divided—this is termed lateral release. Various versions of this soft tissue intervention have been known for many years and were particularly recommended by McBride 5. The technique most widely used today was first described by Mann 6. An intermetatarsal angle of 15 degrees or more necessitates an additional corrective osteotomy at the base of metatarsal I, where the potential for correction is greater (Figure 4b). Many different osteotomy techniques have been described. The simplest are opening osteotomies that are then filled medially with bone, for example from the resected exostosis. At the same time, osteotomies in two planes provide greater stability, because the bony contact surface is increased and the danger of dislocation reduced. After correction the osteotomy has to be stabilized with an implant. Here too, an inexpensive cancellous screw suffices. We take the view that complicated, costly implants such as fixed angle plates are unnecessary. When closing the capsule on the medial side of the metatarsophalangeal joint, the surgeon must take great care to ensure that the capsule is sufficiently tightened after resection of the bony pseudoexostosis.

Figure 4. Severe hallux valgus

Footnote: Radiographs of a foot with severe hallux valgus

(a) Severe deformity with an intermetatarsal angle of 19°, an incongruent metatarsophalangeal joint, and a rigid deformity

(b) After correction by a distal soft tissue intervention with release of the soft tissues on the lateral side and tightening of the soft tissues on the medial side of the metatarsophalangeal joint, with additional correction of the position of metatarsal I by an osteotomy at its base

[Source 1 ]Hallux valgus causes

Hallux valgus are more common in women than men. Hallux valgus can run in the family, in which case they are caused mainly by an inherited weak or faulty structure of the foot. People born with abnormal bones in their feet are more likely to form a bunion.

Hallux valgus can also be caused by:

- conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or cerebral palsy

- diseases such as polio

- injuries to the foot

Wearing shoes that are too narrow and tight can cause bunions in feet that are already prone to this condition. Experts disagree on whether tight shoes alone can cause bunions, but they definitely make them worse.

Avoid high-heeled shoes with pointy tips that squeeze the toes together. The heels tip your body weight forward, putting greater pressure on the toes which are rammed into the end of the shoe.

Hallux valgus symptoms

Hallux valgus symptoms, which occur at the site of the bunion, may include:

- Pain or soreness

- Inflammation and redness

- A burning sensation

- Possible numbness

Symptoms occur most often when wearing shoes that crowd the toes, such as shoes with a tight toe box or high heels. This may explain why women are more likely to have symptoms than men. In addition, spending long periods of time on your feet can aggravate the symptoms of bunions.

Hallux valgus diagnosis

Hallux valgus are readily apparent—the prominence is visible at the base of the big toe or side of the foot. However, to fully evaluate the condition, the foot and ankle surgeon may take x-rays to determine the degree of the deformity and assess the changes that have occurred.

Because bunions are progressive, they do not go away and will usually get worse over time. But not all cases are alike—some bunions progress more rapidly than others. Once your surgeon has evaluated your bunion, a treatment plan can be developed that is suited to your needs.

Hallux valgus treatment

Sometimes observation of the bunion is all that is needed. To reduce the chance of damage to the joint, periodic evaluation and x-rays by your surgeon are advised.

In many other cases, however, some type of treatment is needed. Early treatments are aimed at easing the pain of hallux valgus, but they will not reverse the deformity itself.

The first thing to do is to wear comfortable, softer, wider shoes that allow your toes enough space to spread out. Walk barefoot when possible. Often this eases the discomfort and stops the bunion developing further.

Other ways to reduce the pain and pressure of hallux valgus include:

- Padding. Using special cushioning bunion pads over the area of the bunion can help minimize pain. These can be obtained from your surgeon or purchased at a drug store.

- Activity modifications. Avoid activity that causes bunion pain, including standing for long periods of time.

- Medications. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, may be recommended to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Icing. Applying an ice pack several times a day helps reduce inflammation and pain.

- Injection therapy. Although rarely used in bunion treatment, injections of corticosteroids may be useful in treating the inflamed bursa (fluid-filled sac located around a joint) sometimes seen with bunions.

- Orthotic devices. In some cases, custom orthotic devices such as shoe inserts (orthotics) or orthopedic shoes, may be provided by the foot and ankle surgeon.

- Strapping or taping your toe or foot

If these things don’t work and your foot is deformed or very painful, your doctor might refer you to an orthopedic surgeon. Before agreeing to surgery, ask what is involved and the benefits and risks to you. It can take a long time to recover from bunion surgery.

Figure 5. Hallux valgus splint

Hallux valgus surgery

Your doctor may recommend hallux valgus surgery if you have a bunion that has not gotten better with other treatments, such as shoes with a wider toe box. Hallux valgus surgery corrects the deformity and relieves pain caused by the bump.

The different surgical procedures are based on various underlying principles, e.g., correction osteotomy, resection arthroplasty, or arthrodesis.

Over 150 different operations have been described for the treatment of hallux valgus. A selection of better-known procedures is presented in Table 1 and Figure 6.

Table 1. A selection of well-known surgical procedures for treatment of hallux valgus

| No. | Name | Principle | Site | Advantages/disadvantages | Comments |

| 1 | Akin | Corrective osteotomy | Proximal phalanx | In combination with other techniques, stability technically difficult | Used in hallux valgus interphalangeus |

| 2 | Metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis | Fusion | Metatarsophalangeal joint | Permanent correction, loss of mobility, subsequent osteoarthritis | Used in severe deformities and/or hallux rigidus |

| 3 | Basal osteotomy | Corrective osteotomy | Metatarsal I, proximal | In combination with soft tissue intervention, stability technically difficult, implant necessary, not possible if tarsometatarsal joint is unstable | Suitable for correction of severe deformities |

| 4 | Chevron | Corrective osteotomy | Metatarsal I, distal | Reliable technique, little soft tissue trauma, implant necessary, not possible with severe deformity, reduced perfusion of head of metatarsal I | Used in mild deformities |

| 5 | Hohmann | Corrective osteotomy | Metatarsal I, distal | Little stability with wires or sutures, reduced perfusion of head of metatarsal I | Now hardly ever used |

| 6 | Hueter | Resection arthroplasty | Metatarsal I, head | Simple technique, lack of support for head of metatarsal I, transfer metatarsalgia frequent | No longer used |

| 7 | Keller-Brandes | Resection arthroplasty | Proximal phalanx, proximally | Simple technique, loss of hallux function, transfer metatarsalgia frequent | Used in elderly and inactive patients |

| 8 | Kramer | Corrective osteotomy | Metatarsal I, distal | Little stability with wires, reduced perfusion of head of metatarsal I | Now hardly ever used |

| 9 | Lapidus | Fusion | Tarsometatarsal joint | In combination with soft tissue intervention, implant necessary, loss of mobility, technically difficult, danger of pseudarthroses | Used in cases of TMT-I joint instability or osteoarthritis |

| 10 | McBride | Soft tissue balancing with repositioning of the adductor tendon | Metatarsophalangeal joint | Frequent recurrence owing to inadequate correction of metatarsal I | Now hardly ever used, replaced by soft tissue procedure |

| 11 | Scarf | Corrective osteotomy | Metatarsal I, diaphyseal | Accurate correction angle, implant necessary, extensive soft tissue dissection | Suitable for correction of mild to moderate deformities |

| 12 | Soft tissue procedure | Soft tissue balancing | Metatarsophalangeal joint | Complete soft tissue correction, two skin incisions necessary | Usually in combination with proximal osteotomy |

Figure 6. Hallux valgus correction (the numbers correspond to those in Table 1 above)

[Source 1 ]There are only a small number of prospective randomized trials comparing different surgical procedures or investigating conservative treatment (see Table 2). The whole published literature contains only four publications 7 in which operative techniques were compared, none of which reached any clear conclusions. This shows the limits of current scientific knowledge, particularly when it comes to detailed questions of surgery. Whether, for example, the adductor tendon must be divided or the intermetatarsal angle corrected has to be decided according to the patient’s specific deformity. These techniques can hardly be randomized without taking account of the exact deformity. The wide variety of deformities would necessitate very large numbers of cases, involving the cooperation of many different centers. For this reason, prospective randomized trials concern themselves with details of surgical technique or compare very similar operations. The actual choice of procedure over the whole spectrum of hallux valgus deformities thus depends essentially on the surgeon’s expertise and experience.

A Cochrane review by a group of podiatrists in London, originally published in 2004 and updated in 2009, analyzed a total of 21 randomized or “quasi-randomized” clinical trials that were essentially equivalent to the studies listed in Table 2 with regard to operative technique. The conclusion: “The methodological quality of the….trials was generally poor and trial sizes were small.” No difference was found between conservative treatment and no treatment. No recommendations were given with regard to operative techniques. Trials of operative techniques have yielded inconsistent results; no one technique was superior to all others. Notably, in some studies 25% to 33% of patients were unsatisfied with the outcome of the operation although the relevant angles were improved. The authors of the Cochrane review criticized the maximal 3 years’ postoperative follow-up, writing that 20 to 30 years would be desirable 8.

In the face of the high number of different operations described and the mostly low level of evidence of the investigations published, it is extremely difficult to give treatment recommendations based on high-level evidence. The surgical procedures described in this review reflect the practice in our own institution. Other procedures that are not discussed here may be equally suitable, but any surgery must be specifically designed to eliminate the deformity concerned.

Table 2. Randomized clinical trials of hallux valgus surgery

| Study [reference] | Comparison | Number of patients | Results | Comments |

| Klosok et al. (1993) 9 | Chevron osteotomy versus Wilson osteotomy | 87 | Quicker return to work with Chevron osteotomy, better functional outcome with Wilson osteotomy | Three years’ follow-up, Wilson osteotomy now hardly ever used |

| Resch et al. (1994) 10 | Chevron osteotomy with versus without adductor tenotomy | 84 | Hallux correction 9.8°/7.5° with/without tenotomy, no other differences | Limited relevance, because capsule not divided |

| Connor et al. (1995) 11 | Rehabilitation with versus without continuous motion after Chevron osteotomy | 39 | Mobility better with continuous motion | Only 90 days’ follow-up, limited relevance for treatment |

| Easley et al. (1996) 12 | Curved versus proximal Chevron osteotomy | 97 | No significant differences regarding correction, but swifter and more reliable healing with proximal Chevron osteotomy | Only 2 years’ follow-up, various fixation techniques, limited relevance for treatment |

| Calder et al. (1999) 13 | Suture versus screw fixation in Mitchell osteotomy | 30 | Better results with screws | Superior stability with screws was to be expected, Mitchell osteotomy now seldom used |

| Torkki et al. (2003) 14 | Surgery versus 1-year conservative treatment with or without orthesis | 209 | Surgery superior to conservative treatment after 1 year, no difference after 2 years | Unclear interpretation of data |

| Faber et al. (2004) 15 | Hohmann osteotomy versus Lapidus operation | 101 | No significant difference, also not with regard to hypermobility of first tarsometatarsal joint | No severe deformities included, only 2 years’ follow-up |

| Saro et al. (2007) 16 | Lindgren versus Chevron osteotomy | 100 | No significant differences, both procedures suitable only for mild deformities | Long follow-up (6 years); comparison of two very similar techniques; Lindgren techniques now seldom used |

| Deenik et al. (2008) 17 | Scarf osteotomy versus Chevron osteotomy | 136 | No significant differences, good results in both groups | Comparison of two very similar techniques; the authors recommend Chevron osteotomy because it is technically simpler |

| Tonbul et al. (2009) 18 | Screw versus K-wires for stabilization; curved, distal metatarsal osteotomy | 16 | No significant differences, good results in both groups | Groups too small, limited relevance for treatment |

| du Plessis et al. (2011) 19 | Exercises versus night splint in conservative hallux valgus treatment | 30 | No difference between the groups | Groups too small |

| Pentikäinen et al. (2012) 20 | Chevron osteotomy with fixation (resorbable peg) versus no fixation, with plaster versus elastic bandage postoperatively | 100 | Osteotomy displacement 3.9 mm with fixation versus 3.1 mm without fixation (statistically significant), no difference for postoperative treatment | Accuracy of measurement technique not described, difference clinically irrelevant |

You will be given anesthesia (numbing medicine) so that you won’t feel pain.

- Local anesthesia — Your foot may be numbed with pain medicine. You may also be given medicines that relax you. You will stay awake.

- Spinal anesthesia — This is also called regional anesthesia. The pain medicine is injected into a space in your spine. You will be awake but will not be able to feel anything below your waist.

- General anesthesia — You will be asleep and pain-free.

The surgeon makes a cut around the toe joint and bones. The deformed joint and bones are repaired using pins, screws, plates, or a cast to keep the bones in place.

Your surgeon may repair the hallux valgus by:

- Making certain tendons or ligaments shorter or longer.

- Taking out the damaged part of the joints and then using screws, wires, or a plate to hold the joint together so that they can fuse.

- Shaving off the bump on the toe joint.

- Removing the damaged part of the joint.

- Cutting parts of the bones on each side of the toe joint, and then putting them in their proper position.

Most people go home the same day they have bunion removal surgery.

Your doctor will tell you how to take care of yourself after surgery.

You should have less pain after your bunion is removed and your foot has healed. You should also be able to walk and wear shoes more easily. This surgery does repair some of the deformity of your foot, but it will not give you a perfect-looking foot.

Full recovery may take 3 to 5 months.

Hallux valgus surgery risks

Risks for anesthesia and surgery in general include:

- Allergic reactions to medicines

- Breathing problems

- Bleeding

- Pain

- Bleeding

- Infection of the surgical site (wound)

- Unsightly scarring

- Blood clots

- Difficulty passing urine

Risks for hallux valgus surgery include:

- Numbness in the big toe

- The wound does not heal well

- Problems with bone healing

- The surgery does not correct the problem

- Instability of the toe

- Nerve damage

- Pain in the ball of your foot

- Severe pain, stiffness and loss of use of your foot (complex regional pain syndrome)

- Stiffness in the toe

- Arthritis in the toe

- The deformity coming back

- Wülker N, Mittag F. The treatment of hallux valgus. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(49):857-67; quiz 868. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3528062

- Austin DW, Leventeen EO. A new osteotomy for hallux valgus. Clin Orthop. 1981;157:25–30

- Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nix S, Smith M, Vicenzino B. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010 Sep 27; 3():21.

- Factors associated with hallux valgus in a population-based study of older women and men: the MOBILIZE Boston Study. Nguyen US, Hillstrom HJ, Li W, Dufour AB, Kiel DP, Procter-Gray E, Gagnon MM, Hannan MT. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010 Jan; 18(1):41-6.

- Mc Bride ED. A conservative operation for bunions. J Bone Joint Surg. 1928;10:735–739.

- Mann RA, Rudicel S, Graves SC. Repair of hallux valgus with a distal soft-tissue procedure and proximal metatarsal osteotomy. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:124–129.

- Equivalent correction in scarf and chevron osteotomy in moderate and severe hallux valgus: a randomized controlled trial. Deenik A, van Mameren H, de Visser E, de Waal Malefijt M, Draijer F, de Bie R. Foot Ankle Int. 2008 Dec; 29(12):1209-15.

- Interventions for treating hallux valgus (abductovalgus) and bunions. Ferrari J, Higgins JP, Prior TD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; (1):CD000964.

- Klosok JK, Pring DJ, Jessop JH, Maffulli N. Chevron or Wilson metatarsal osteotomy for hallux valgus.0 A prospective randomised trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:825–829

- Resch S, Stenström A, Reynisson K, Jonsson K. Chevron osteotomy for hallux valgus not improved by additional adductor tenotomy. A prospective, randomized study of 84 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65:541–544

- Connor JC, Berk DM, Hotz MW. Effects of continuous passive motion following Austin bunionectomy. A prospective review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1995;85:744–748

- Easley ME, Kiebzak GM, Davis WH, Anderson RB. Prospective, randomized comparison of proximal crescentic and proximal chevron osteotomies for correction of hallux valgus deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:307–316

- Calder JD, Hollingdale JP, Pearse MF. Screw versus suture fixation of Mitchell’s osteotomy. A prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:621–624.

- Torkki M, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S, Hoikka V, Laippala P, Paavolainen P. Hallux valgus: immediate operation versus 1 year of waiting with or without orthoses: a randomized controlled trial of 209 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:209–215.

- Faber FW, Mulder PG, Verhaar JA. Role of first ray hypermobility in the outcome of the Hohmann and the Lapidus procedure. A prospective, randomized trial involving one hundred and one feet. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(A3):486–495

- Saro C, Andrén B, Wildemyr Z, Felländer-Tsai L. Outcome after distal metatarsal osteotomy for hallux valgus: a prospective random-ized controlled trial of two methods. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:778–787.

- Deenik A, van Mameren H, de Visser E, de Waal Malefijt M, Draijer F, de Bie R. Equivalent correction in scarf and chevron osteotomy in moderate and severe hallux valgus: a randomized controlled trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:1209–1215

- Tonbul M, Baca E, Ada M, Ozbaydar MU, Yurdoðlu HC. Crescentic distal metatarsal osteotomy for the treatment of hallux valgus: a prospective, randomized, controlled study of two different fixation methods. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2009;43:497–503

- du Plessis M, Zipfel B, Brantingham JW, et al. Manual and manipulative therapy compared to night splint for symptomatic hallux abducto valgus: an exploratory randomised clinical trial. Foot (Edinb) 2011;21:71–78.

- Pentikäinen IT, Ojala R, Ohtonen P, Piippo J, Leppilahti JI. Radiographic analysis of the impact of internal fixation and dressing choice of distal chevron osteotomy: randomized control trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33:420–423.