Hangnail

A hangnail is a small, loose strip of torn skin near a fingernail or toenail, more specifically a small strip or shred of eponychium or paronychium that separates from the side of the cuticle of a fingernail or toenail. Hangnails are usually caused by dry skin or (in the case of fingernails) nail biting, and may be prevented with proper moisturization of your skin. The term “hangnail” is misleading, as a hangnail is not an actual part of the nail. It’s dead, dried skin, not nail, the latter being made up of mostly calcium and a fibrous protein, known as keratin.

When attempting to remove a hangnail, additional skin may be painfully ripped off if its attachment is not broken properly. This may lead to a painful infection called paronychia. Therefore, hangnails should usually be cut using nail scissors or a nail clipper; biting them frequently makes it worse. People with a hangnail should be careful to cut it all off and rub hand lotion into the cuticles two to three times a day.

Simple home treatment can help prevent problems with hangnails:

- Do not pull at or bite off a hangnail. This may cause the skin to rip.

- Clip off the hangnail neatly with sharp, clean cuticle scissors.

- Massage hand lotion or cream into your cuticles 2 to 3 times each day.

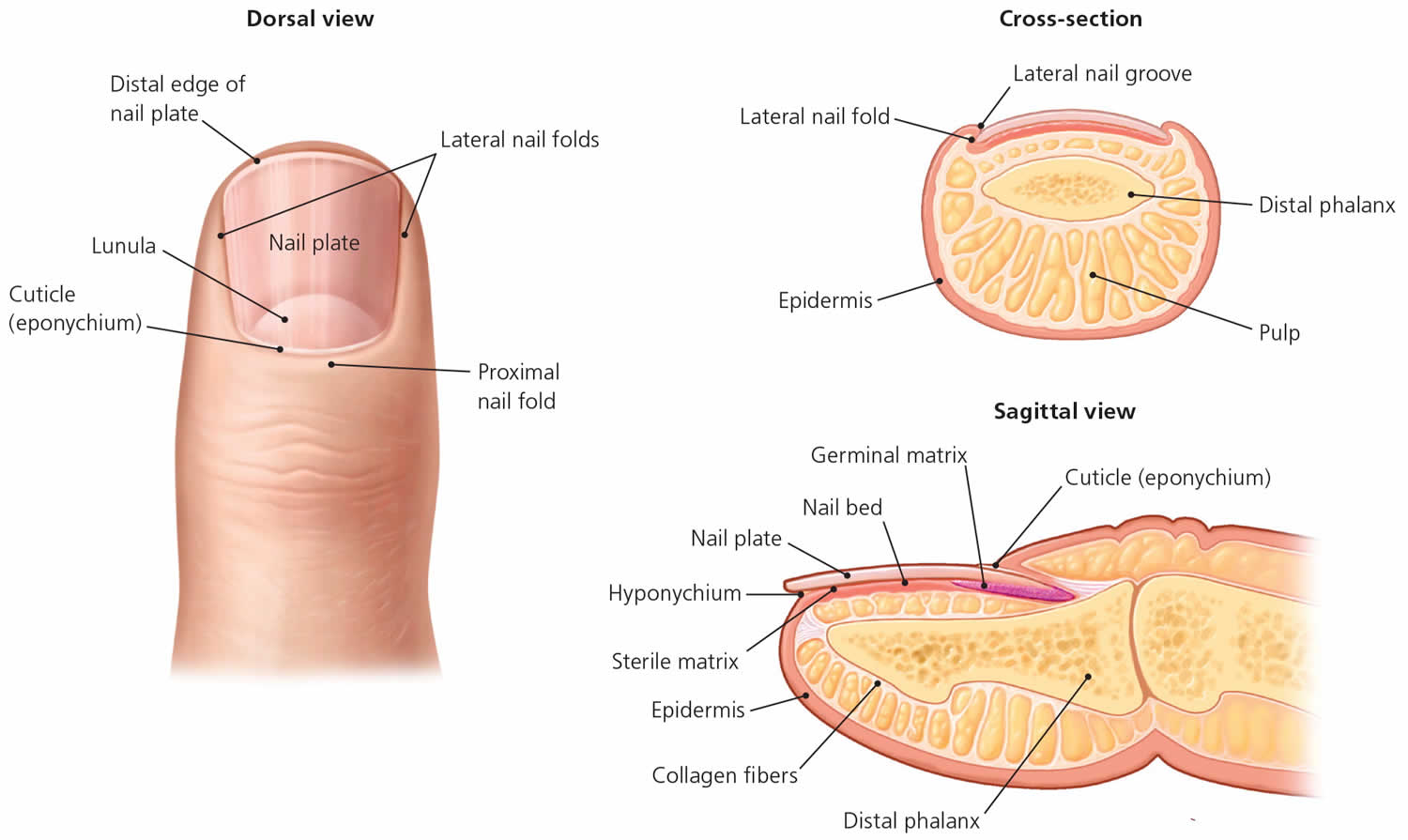

Nail anatomy

The relevant anatomy includes the nail bed, nail plate, and perionychium1 (Figure 1). The nail bed is composed of a germinal matrix, which can be seen as the lunula, the crescent-shaped white area at the most proximal portion of the nail. The germinal matrix is responsible for new nail growth. The more distal portion of the nail bed is made by the flesh-colored sterile matrix, which is responsible for strengthening the nail plate. The perionychium comprises the three nail folds (two lateral and one proximal) and the nearby nail bed.

The proximal nail fold is unique compared with the two lateral folds. The nail plate itself arises from a mild depression in the proximal nail fold. The nail divides the proximal nail fold into two parts, the dorsal roof and the ventral floor, both of which contain germinal matrices. The eponychium also called the cuticle, is an outgrowth of the proximal nail fold, forms a watertight barrier between the nail plate and the skin, protecting the underlying skin from pathogens and irritants 1.

Figure 1. Nail anatomy

Infected hangnail

Infected hangnail commonly called paronychia or whitlow, is inflammation of the skin around a finger or toenail. Infected hangnail can be acute (< 6 weeks) or chronic (persisting > 6 weeks). Infected hangnail may be associated with felon (infection of the pulp of the fingertip). Infected hangnail (paronychia) usually affects the fingernails, whereas ingrown nails (onychocryptosis) are more common with the toenails 2. Ingrown toenails resulting from abnormal growth of the nail plate into the nail fold are a cause of acute infected hangnail 3. Although prevalence data are lacking, acute infected hangnail is one of the most common hand infections in the United States. It is three times more common in women, possibly because of more nail manipulation in this population 4.

Acute infected hangnail usually involves only one digit at a time; more widespread disease warrants a broader investigation for systemic issues 1. Chronic infected hangnail typically involves multiple digits.

Acute infected hangnail can affect anyone. However, infected hangnail is more likely to follow a break in the skin, especially between the proximal nail fold/cuticle and the nail plate. For example:

- If the nail is bitten (onychophagia) or the nail-fold is habitually picked

- In infants that suck their fingers or thumbs

- Following manicuring

- Ingrown toenails (onychocryptosis)

- On application of sculptured or artificial fingernails

- Treatment with oral retinoid that dries the skin (acitretin, isotretinoin)

- Other drugs, including epidermal growth factor receptor and BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib)

Chronic infected hangnail mainly occurs in people with hand dermatitis, or who have constantly cold and wet hands, such as:

- Dairy farmers

- Fishermen

- Bar tenders

- Cleaners

- Housewives

- People with poor circulation

Acute and chronic skin infections tend to be more frequent and aggressive in patients with diabetes or chronic debility, or that are immune suppressed by drugs or disease.

Figure 2. Infected hangnail (acute infected hangnail is characterized by the rapid onset of erythema, edema, and tenderness at the proximal nail folds)

Infected hangnail causes

Acute infected hangnail

Acute infected hangnail is the result of a disruption of the protective barrier of the nail folds. Once this barrier is breached, various pathogens can create inflammation and infection. Acute infected hangnail is usually due to bacterial infection with Staphylococcus aureus which may be multiresistant to antibiotics, Streptococcus pyogenes, pseudomonas, or other bacterial pathogens. Infected hangnail can also be due to the cold sore virus, Herpes simplex, and the yeast, Candida albicans. Pseudomonas infections can be identified by a greenish discoloration in the nail bed (Figure 3) 5. The differential diagnosis of acute infected hangnail includes a felon, which is an infection in the finger pad or pulp 6. Although acute infected hangnail can lead to felons, they are differentiated by the site of the infection.

Patients typically present with rapid onset of an acute, inflamed nail fold and accompanying pain (Figure 2). The diagnosis is clinical, but imaging may be useful if a deeper infection is suspected 7. It is not helpful to send expressed fluid for culture because the results are often nondiagnostic and do not affect management 8. In a study of patients requiring hospitalization for infected hangnail who underwent incision and drainage with culture, only 4% of the cultures were positive, with a polymicrobial predominance of bacteria 7.

Most common risk factors of nail fold disruption 9

- Accidental trauma

- Artificial nails

- Manicures

- Manipulating a hangnail (i.e., shred of eponychium)

- Occupational trauma (e.g., bartenders, housekeepers, dishwashers, laundry workers)

- Onychocryptosis (i.e., ingrown nails)

- Onychophagia (nail biting)

Figure 3. Pseudomonas infected hangnail is typically caused by repeated minor trauma in a wet environment and often causes a green discoloration.

Chronic infected hangnail

The cause or causes of chronic infected hangnail are not fully understood. In many cases, it is due to from irritant dermatitis of the nail fold rather than an infection 1. Common irritants include acids, alkalis, or other chemicals commonly used by housekeepers, dishwashers, bartenders, laundry workers, florists, bakers, and swimmers. Once the protective nail barrier is disrupted, repeated exposure to irritants may result in chronic inflammation. Chronic infected hangnail is diagnosed clinically based on symptom duration of at least six weeks, a positive exposure history, and clinical findings consistent with nail dystrophy (see Figure 4 below) 9. The cuticle may be totally absent, and Beau lines (deep side-to-side grooves in the nail that represent interruption of nail matrix maturation) may be present 10. Multiple digits typically are involved. If only a single digit is affected, the possibility of malignancy, such as squamous cell cancer, must be considered 9. The presence of pus and redness may indicate an acute exacerbation of a chronic process.

Often several different micro-organisms can be cultured, particularly Candida albicans and the Gram negative bacilli, pseudomonas.

Fungal infections are thought to represent colonization, not a true pathogen, so antifungals are generally not used to treat chronic paronychia 11. Several classes of medications can cause chronic paronychia: retinoids, protease inhibitors (4% of users), antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibodies (17% of users), and several classes of chemotherapeutic agents (35% of users) 12. The effect can be immediate or delayed up to 12 months.

Infected hangnail prevention

Recommendations to prevent recurrent infected hangnail (recommendations are based on expert opinion rather than clinical evidence) 13:

- Apply moisturizing lotion after hand washing.

- Avoid chronic prolonged exposure to contact irritants and moisture (including detergent and soap).

- Avoid nail trauma, biting, picking, and manipulation, and finger sucking.

- Avoid trimming cuticles or using cuticle removers.

- Improve glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus.

- Keep affected areas clean and dry.

- Keep nails short.

- Provide adequate patient education.

- Use rubber gloves, preferably with inner cotton glove or cotton liners when exposed to moisture and/or irritants.

Infected hangnail symptoms

Acute infected hangnail

Acute infected hangnail develops rapidly over a few hours, and usually affects a single nail fold. Symptoms are pain, redness and swelling.

If herpes simplex is the cause, multiple tender vesicles may be observed. Sometimes yellow pus appears under the cuticle and can evolve to abscess. The nail plate may lift up (onycholysis). Acute paronychia due to Streptococcus pyogenes may be accompanied by fever, lymphangiitis and tender lymphadenopathy.

Acute candida more commonly infects the proximal nail fold (see Figure 2 above).

Chronic infected hangnail

Chronic infected hangnail is a gradual process. It may start in one nail fold, particularly the proximal nail fold, but often spreads laterally and to several other fingers. Each affected nail fold is swollen and lifted off the nail plate. This allows entry of organisms and irritants.The affected skin may be red and tender from time to time, and sometimes a little pus (white, yellow or green) can be expressed from under the cuticle.

The nail plate thickens and is distorted, often with transverse ridges.

Figure 4. Chronic infected hangnail with typical loss of cuticle

Infected hangnail complications

Acute infected hangnail can spread to cause a serious hand infection (cellulitis) and may involve underlying tendons (infectious tendonitis).

The main complication of chronic infected hangnail is nail dystrophy. It is often associated with distorted, ridged nail plates. They may become yellow or green/black and brittle. After recovery, it takes up to a year for the nails to grow back to normal.

Infected hangnail diagnosis

Infected hangnail is a clinical diagnosis, other diagnostic tools such as radiography or laboratory tests are needed only if the clinical presentation is atypical. Imaging test may be useful if a deeper infection is suspected 7. It is not helpful to send expressed fluid for culture because the results are often nondiagnostic and do not affect management 8.

- Gram stain microscopy may reveal bacteria

- Potassium hydroxide microscopy may reveal fungi

- Bacterial culture

- Viral swabs

- Tzanck smears

- Nail clippings for culture (mycology).

If there is uncertainty about the presence of an abscess, ultrasonography can be performed. Fluid collection indicates an abscess, whereas a subcutaneous cobblestone appearance indicates cellulitis 14. The digital pressure test has been suggested as an alternative to confirm the presence of an abscess. To perform the test, the patient opposes the thumb and affected finger, applying light pressure to the distal volar aspect of the affected digit. The pressure within the nail fold causes blanching of the overlying skin and clear demarcation of an abscess, if present 15.

Infected hangnail treatment

Acute infected hangnail treatment

- Soak affected digit in warm water, several times daily.

- Topical antiseptic may be prescribed for localized, minor infection.

- Oral antibiotics may be necessary for severe or prolonged bacterial infection; often a tetracycline such as doxycycline is prescribed.

- Consider early treatment with aciclovir in case of severe herpes simplex infection.

- Surgical incision and drainage may be required for abscess followed by irrigation and packing with gauze.

- Rarely, the nail must be removed to allow pus to drain.

Treatment of acute infected hangnail is based on the severity of inflammation and the presence of an abscess. If only mild inflammation is present and there is no overt cellulitis, treatment consists of warm soaks, topical antibiotics with or without topical steroids, or a combination of topical therapies. Warm soaks have been advocated to assist with spontaneous drainage 16. Although they have not been extensively studied, Burow solution (aluminum acetate solution) and vinegar (acetic acid) combined with warm soaks have been used for years as a topical treatment. Burow solution has astringent and antimicrobial properties and has been shown to help with soft tissue infections 17. Similarly, 1% acetic acid has been found effective for treating multidrug-resistant pseudomonal wound infections because of its antimicrobial properties 18. Soaking can lead to desquamation, which is normal 19. Topical antibiotics for infected hangnail include mupirocin (Bactroban), gentamicin, or a topical fluoroquinolone if pseudomonal infection is suspected. Neomycin-containing compounds are discouraged because of the risk of allergic reaction (approximately 10%) 20. The addition of topical steroids decreases the time to symptom resolution without additional risks 21.

If an abscess is present, it should be opened to facilitate drainage. Soaking combined with other topical therapies can be tried, but if no improvement is noted after two to three days or if symptoms are severe, the abscess must be mechanically drained 9. No randomized controlled trials have compared methods of drainage, and treatment should be individualized according to the clinical situation and skill of the physician. An instrument such as a nail elevator or hypodermic needle can be inserted at the junction of the affected nail fold and nail 22.

Once the abscess has been opened, spontaneous drainage should occur. If it does not, the digit can be massaged to express the fluid from the opening. If massage is unsuccessful, a scalpel can be used to create a larger opening at the same nail fold–nail junction. If spontaneous drainage still does not occur, the scalpel can be rotated with the sharp side down to avoid cutting the skin fold. Spontaneous drainage should ensue, but if it does not, the area should be massaged to facilitate drainage. The skin directly over the abscess can be opened with a needle or scalpel if elevation of the nail fold and nail does not result in drainage. Ultrasonography can be performed if there is uncertainty about whether an abscess exists or if difficulty is encountered with abscess drainage 23.

Anesthesia is generally not needed when using a needle for drainage 22. More extensive procedures will likely require anesthesia. Applying ice packs or vapocoolant spray may suffice. If not, infiltrative or digital block anesthesia should be administered. Infiltrative anesthesia or a wing block is faster than a digital block and has less risk of damaging proximal digital blood vessels and nerves 24. A wing block is accomplished by inserting a 30-gauge or smaller needle just proximal to the eponychium and slowly administering anesthetic until the skin blanches (see YouTube video below). The needle is then directed to each lateral nail fold, and another small bolus of anesthetic is delivered until the skin blanches. Significant resistance is often encountered because of the small needle gauge and tight space. The needle is then removed and reinserted distally along each lateral nail fold until the entire dorsal nail tip is anesthetized. The anesthetic must be injected slowly to avoid painful tissue distension. The pulp and finger pad should not be injected. Several anesthetic agents are available, but 1% to 2% lidocaine is most common. Lidocaine with epinephrine is safe to use in patients with no risk factors for vasospastic disease (e.g., peripheral vascular disease, Raynaud phenomenon). The use of epinephrine allows for a nearly bloodless field without the use of a tourniquet and prolongs the effect of the anesthesia. Buffering and warming the anesthetic aids in patient comfort 25.

A wider incision may be needed if the infection extends around the nail. If the entire eponychium is involved, the nail plate can be removed or the Swiss roll technique (reflection of the proximal nail fold) can be performed 26. The Swiss roll technique involves parallel incisions from the eponychium just distal to the distal interphalangeal joint. The tissue is folded over a small piece of non-adherent gauze and sutured to the digit on each side. The exposed nail bed is thoroughly irrigated and dressed with non-adherent gauze, then reevaluated in 48 hours. If no signs of infection are present, the sutures can be removed and the flap of skin returned and left to heal by secondary intention.

Antibiotics are generally not needed after successful drainage 27. Prospective studies have shown that the addition of systemic antibiotics does not improve cure rates after incision and drainage of cutaneous abscesses, even in those due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus 28, which is more common in athletes, children, prisoners, military recruits, residents of long-term care facilities, injection drug users, and those with previous infections 29. Post-drainage soaking with or without Burow solution or 1% acetic acid is generally recommended two or three times per day for two to three days, except after undergoing the Swiss roll technique. The addition of a topical antibiotic and/or steroids can be considered, but there are no evidence-based recommendations to guide this decision.

The use of oral antibiotics should be limited 8. Patients with overt cellulitis and possibly those who are immunocompromised or severely ill may warrant oral antibiotics 28. When they are required, therapy should be directed against the most likely pathogens. If there are risk factors for oral pathogens, such as thumb-sucking or nail biting, medications with adequate anaerobic coverage should be used. Table 1 lists common pathogens and suggested antibiotic options 1., but local community resistance patterns should be considered when choosing specific agents 29.

Recurrent acute infected hangnail can progress to chronic infected hangnail. Therefore, patients should be counseled to avoid trauma to the nail folds. Systemic diseases such as psoriasis and eczema can cause acute infected hangnail; in these cases, treatment should be directed at the underlying cause.

Table 1. Treatment options for typical pathogens associated with acute infected hangnail

| Pathogen | Antibiotic options |

|---|---|

Gram-negative aerobes | |

Fusobacterium | Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), clindamycin, fluoroquinolones |

Pseudomonas | Ciprofloxacin |

Gram-negative anaerobe | |

Bacteroides | Amoxicillin/clavulanate, clindamycin, fluoroquinolones |

Gram-negative facultative anaerobes | |

Eikenella | Cefoxitin |

Enterococcus | Amoxicillin/clavulanate |

Klebsiella | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, fluoroquinolones |

Proteus | Amoxicillin/clavulanate, fluoroquinolones |

Gram-positive aerobes | |

Staphylococcus | Cephalexin (Keflex) |

For suspected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: clindamycin, doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | |

Streptococcus | Cephalexin |

Footnote: Local community resistance patterns should always be considered when choosing antibiotics.

[Sources 1, 7 ]Chronic infected hangnail treatment

Treatment of chronic infected hangnail consists of stopping the source of irritation, controlling inflammation, and restoring the natural protective barrier 6. Topical anti-inflammatory agents, steroids, or calcineurin inhibitors are the mainstay of therapy 30. In a randomized, unblinded, comparative study, tacrolimus 0.1% (Protopic) was more effective than betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% 30. In severe or refractory cases, more aggressive treatments may be required to stop the inflammation and restore the barrier. If the Swiss roll technique is used, the nail bed will need to be exposed for a longer duration (seven to 14 days) than for acute cases (two to three days) 26.

If a medication is the cause, the physician and patient must decide whether the side effects are acceptable for the therapeutic effect of the drug. Discontinuing the medication should reverse the process and allow healing. Doxycycline has been found effective for treatment of infected hangnail caused by antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibodies 9. A case report describes successful treatment with twice-daily application of a 1% solution of povidone/iodine in dimethyl sulfoxide until symptom resolution in patients with chemotherapy-induced chronic infected hangnail 31. Zinc deficiency is known to cause nail plate abnormalities and chronic infected hangnail; treatment with 20 mg of supplemental zinc per day is helpful 32. It is important to inform the patient that the process can take weeks to months to restore the natural barrier. Effective strategies to avoid offending irritants are listed in prevention section above.

Attend to predisposing factors:

- Keep the hands dry and warm.

- Avoid wet work, or use totally waterproof gloves that are lined with cotton.

- Keep fingernails scrupulously clean.

- Wash after dirty work with soap and water, rinse off and dry carefully.

- Apply emollient hand cream frequently – dimeticone barrier creams may help.

Treatment should focus on the dermatitis and any microbes grown on culture 33.

- Topical corticosteroid ointment is applied for 2–4 weeks and repeated for flares.

- Tacrolimus ointment is an alternative when dermatitis is not responding to routine management 34.

- Intralesional steroid injections are sometimes used in resistant cases.

- Antiseptics or antifungal lotions or solutions may be applied for several months.

- Oral antifungal agent (itraconazole or fluconazole), if Candida albicans is confirmed.

Other management

- Patients with diabetes and vascular disease with toenail paronychia infections should be examined for signs of cellulitis.

- Surgical excision of the proximal nail fold may be necessary.

- Eponychial marsupialisation involves surgical removal of a narrow strip of skin next to the nail, to reduce the risk of infection 35.

- Swiss roll technique has the advantage of retaining the nail plate and quicker recovery 36.

Infected hangnail prognosis

Acute infected hangnail usually clears completely in a few days, and rarely recurs in healthy individuals.

Chronic infected hangnail may persist for months or longer, and can recur in predisposed individuals.

References- Chang P. Diagnosis using the proximal and lateral nail folds. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(2):207–241.

- Acute and Chronic Paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Jul 1;96(1):44-51. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0701/p44.html

- Heidelbaugh JJ, Lee H. Management of the ingrown toenail. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(4):303–308.

- Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(6):1113–1116.

- Biesbroeck LK, Fleckman P. Nail disease for the primary care provider. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(6):1213–1226.

- Shafritz AB, Coppage JM. Acute and chronic paronychia of the hand. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(3):165–174.

- Fowler JR, Ilyas AM. Epidemiology of adult acute hand infections at an urban medical center. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1189–1193.

- Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA. 2016;316(3):325–337.

- Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, Alevizos A. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(3):339–346.

- Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(8):779–787.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Ghetti E, Colombo MD. Topical steroids versus systemic antifungals in the treatment of chronic paronychia: an open, randomized double-blind and double dummy study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(1):73–76.

- Habif TP. Nail disorders. In: Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier; 2016:960–985.

- Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Gregoriou S, Alevizos A. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(3):343.

- Marin JR, Dean AJ, Bilker WB, Panebianco NL, Brown NJ, Alpern ER. Emergency ultrasound-assisted examination of skin and soft tissue infections in the pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):545–553.

- Turkmen A, Warner RM, Page RE. Digital pressure test for paronychia. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(1):93–94.

- Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, eds. Hand. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders; 2013:534–570.

- Jinnouchi O, Kuwahara T, Ishida S, et al. Anti-microbial and therapeutic effects of modified Burow’s solution on refractory otorrhea. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39(4):374–377.

- Nagoba BS, Selkar SP, Wadher BJ, Gandhi RC. Acetic acid treatment of pseudomonal wound infections—a review. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6(6):410–415.

- Madhusudhan VL. Efficacy of 1% acetic acid in the treatment of chronic wounds infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa prospective randomised controlled: clinical trial. Int Wound J. 2015;13(6):1129–1136.

- Gehrig KA, Warshaw EM. Allergic contact dermatitis to topical antibiotics: epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):1–21.

- Wollina U. Acute paronychia: comparative treatment with topical antibiotic alone or in combination with corticosteroid. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(1):82–84.

- Ogunlusi JD, Oginni LM, Ogunlusi OO. DAREJD simple technique of draining acute paronychia. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2005;9(2):120–121.

- Alsaawi A, Alrajhi K, Alshehri A, Ababtain A, Alsolamy S. Ultrasonography for the diagnosis of patients with clinically suspected skin and soft tissue infections: a systematic review of the literature. European Journal of Emergency Medicine: June 2017 – Volume 24 – Issue 3 – p 162–169 doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000340

- Jellinek NJ, Vélez NF. Nail surgery: best way to obtain effective anesthesia. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(2):265–271.

- Latham JL, Martin SN. Infiltrative anesthesia in office practice. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(12):956–962.

- Pabari A, Iyer S, Khoo CT. Swiss roll technique for treatment of paronychia. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2011;15(2):75–77.

- Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC, Agudelo Higuita NI. Skin and soft tissue infections. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(6):474–483.

- Duong M, Markwell S, Peter J, Barenkamp S. Randomized, controlled trial of antibiotics in the management of community-acquired skin abscesses in the pediatric patient. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(5):401–407.

- Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1357]. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):380–390.

- Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Belyayeva E, Larios G, Kontochristopoulos G, Katsambas A. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% vs. betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% in the treatment of chronic paronychia: an unblinded randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(4):858–860.

- Capriotti K, Capriotti JA. Chemotherapy-associated paronychia treated with a dilute povidone-iodine/dimethylsulfoxide preparation. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:489–491.

- Iorizzo M. Tips to treat the 5 most common nail disorders: brittle nails, onycholysis, paronychia, psoriasis, onychomycosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(2):175–183.

- Relhan V, Goel K, Bansal S, Garg VK. Management of chronic paronychia. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):15–20. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.123482 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884921

- Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Belyayeva E, Larios G, Kontochristopoulos G, Katsambas A. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% vs. betamethasone 17-valerate 0.1% in the treatment of chronic paronychia: An unblinded randomized study. Br J Dermatol. 2009 Apr;160(4):858-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08988.x. Epub 2008 Dec 16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08988.x

- Bednar MS, Lane LB. Eponychial marsupialization and nail removal for surgical treatment of chronic paronychia. J Hand Surg Am 1991;16:314-7.

- Swiss roll technique for treatment of paronychia. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2011 Jun;15(2):75-7. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181ec089e.