Avocado

The avocado (Persea americana) originated in Mexico, Central or South America, and was first cultivated in Mexico as early as 500 BC 1. The first English language mention of avocado was in 1696. In 1871, avocados were first introduced to the United States in Santa Barbara, California, with trees from Mexico. By the 1950s, there were over 25 avocado varieties commercially packed and shipped in California, with Fuerte accounting for about two-thirds of the production. As the large-scale expansion of the avocado industry occurred in the 1970s, the Hass avocado cultivar replaced Fuerte as the leading California variety and subsequently became the primary global variety 1. The Hass avocado contains about 136 g of pleasant, creamy, smooth texture edible fruit covered by a thick dark green, purplish black, and bumpy skin. The avocado seed and skin comprise about 33% of the total whole fruit weight 2. Avocados are a farm-to-market food; they require no processing, preservatives or taste enhancers. The avocado’s natural skin eliminates the need for packaging and offers some disease and insect resistance, which allows them to be grown in environmentally sustainable ways.

Although the U.S. Nutrition Labeling and Education Act defines the serving size of an avocado as one-fifth of a fruit, or 30 g (1 ounce), the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2006 finds that the average consumption is one-half an avocado (approximately 68 g) 3.

The nutrition and phytochemical composition of avocados is summarized in Table 1.

One-half an avocado is a nutrient and phytochemical dense food consisting of the following: dietary fiber (4.6 g), total sugar (0.2 g), potassium (345 mg), sodium (5.5 mg), magnesium (19.5 mg), vitamin A (5.0 μg RAE), vitamin C (6.0 mg), vitamin E (1.3 mg), vitamin K1 (14 μg), folate (60 mg), vitamin B-6 (0.2 mg), niacin (1.3 mg), pantothenic acid (1.0 mg), riboflavin (0.1 mg), choline (10 mg), lutein/zeaxanthin (185 μg), cryptoxanthin (18.5 μg), phytosterols (57 mg), and high-monounsaturated fatty acids (6.7 g) and 114 kcals or 1.7 kcal/g (after adjusting for insoluble dietary fiber), which may support a wide range of potential health effects 4. Avocados contain an oil rich in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) in a water based matrix, which appears to enhance nutrient and phytochemical bioavailability and masks the taste and texture of the dietary fiber 5. Avocados are a medium energy dense fruit because about 80% of the avocado edible fruit consists of water (72%) and dietary fiber (6.8%) and has been shown to have similar effects on weight control as low-fat fruits and vegetables 6. An analysis of adult data from the NHANES 2001–2006 suggests that avocado consumers have higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol also known as the “good” cholesterol, lower risk of metabolic syndrome, and lower weight, BMI, and waist circumference than nonconsumers 7. One avocado fruit (136 g) has nutrient and phytochemical profiles similar to 1.5 ounces (42.5 g) of tree nuts (almonds, pistachios, or walnuts), which have qualified heart health claims 4 (Table 2).

Table 1. Avocado Calories – Carbs – Protein – Fiber – Nutrition Content

| Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g | cup, cubes 150 g | cup, pureed 230 g | cup, sliced 146 g | Avocado, Florida or California 201 g | |

| Approximates | |||||||

| Water | g | 73.23 | 109.84 | 168.43 | 106.92 | 147.19 | |

| Energy | kcal | 160 | 240 | 368 | 234 | 322 | |

| Protein | g | 2 | 3 | 4.6 | 2.92 | 4.02 | |

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 14.66 | 21.99 | 33.72 | 21.4 | 29.47 | |

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 8.53 | 12.79 | 19.62 | 12.45 | 17.15 | |

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 6.7 | 10.1 | 15.4 | 9.8 | 13.5 | |

| Sugars, total | g | 0.66 | 0.99 | 1.52 | 0.96 | 1.33 | |

| Minerals | |||||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 12 | 18 | 28 | 18 | 24 | |

| Iron, Fe | mg | 0.55 | 0.82 | 1.27 | 0.8 | 1.11 | |

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 29 | 44 | 67 | 42 | 58 | |

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 52 | 78 | 120 | 76 | 105 | |

| Potassium, K | mg | 485 | 728 | 1116 | 708 | 975 | |

| Sodium, Na | mg | 7 | 10 | 16 | 10 | 14 | |

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.64 | 0.96 | 1.47 | 0.93 | 1.29 | |

| Vitamins | |||||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 10 | 15 | 23 | 14.6 | 20.1 | |

| Thiamin | mg | 0.067 | 0.101 | 0.154 | 0.098 | 0.135 | |

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.13 | 0.195 | 0.299 | 0.19 | 0.261 | |

| Niacin | mg | 1.738 | 2.607 | 3.997 | 2.537 | 3.493 | |

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0.257 | 0.386 | 0.591 | 0.375 | 0.517 | |

| Folate, DFE | µg | 81 | 122 | 186 | 118 | 163 | |

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 7 | 10 | 16 | 10 | 14 | |

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 146 | 219 | 336 | 213 | 293 | |

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 2.07 | 3.1 | 4.76 | 3.02 | 4.16 | |

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 21 | 31.5 | 48.3 | 30.7 | 42.2 | |

| Lipids | |||||||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 2.126 | 3.189 | 4.89 | 3.104 | 4.273 | |

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 9.799 | 14.698 | 22.538 | 14.307 | 19.696 | |

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 1.816 | 2.724 | 4.177 | 2.651 | 3.65 | |

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | |||||||

| Caffeine | mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Table 2. Avocado compared to tree nut qualified health claims reference amount

| Nutrient | Hass avocado 1 fruit (136 g) | Almonds 1.5 oz (42.5 g) | Pistachios 1.5 oz (42.5 g) | Walnuts 1.5 oz (42.5 g) |

| Water (g) | 98.4 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.7 |

| Calories (kcal) | 227 | 254 | 240 | 278 |

| Calories (kcal) (insoluble fiber adjusted) | 201 | 239 | 235 | 269 |

| Total fat (g) | 21 | 22.1 | 19.1 | 27.7 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 13.3 | 13.8 | 10.1 | 3.8 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 2.5 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 20 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 2.9 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Protein (g) | 2.7 | 9 | 9 | 6.5 |

| Total Carbohydrate (g) | 11.8 | 9 | 12.2 | 5.8 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 9.2 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 2.9 |

| Potassium (mg) | 690 | 303 | 450 | 188 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 39 | 120 | 48 | 68 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 12 | 0 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| Folate (mcg) | 121 | 23 | 21 | 42 |

| Vitamin B-6 (mg) | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Niacin (mg) | 2.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.3 | 0.15 |

| Pantothenic acid (mg) | 2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Vitamin K (ug) | 28.6 | 0 | 6.3 | 1.2 |

| Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol) (mg) | 2.7 | 10.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| γ-Tocopherol (mg) | 0.44 | 0.3 | 9 | 8.9 |

| Lutein + zeaxanthin (ug) | 369 | 0 | 494 | 4.5 |

| Total phytosterols (mg) | 113 | 54 | 123 | 30 |

How To Choose and Use Avocado

There are hundreds of types of avocados, but seven avocado varieties (Bacon, Fuerte, Gwen, Hass, Lamb Hass, Pinkerton, Reed and Zutano) are grown commercially in California. The Hass variety accounts for approximately 95 percent of the total crop each year – which runs from Spring to Fall.

Many varieties are available as certified organic fruit.

How to know when your avocado is ripe

- The best way to tell if an avocado is ripe and ready for immediate use is to gently squeeze the fruit in the palm of your hand. Ripe, ready-to-eat fruit will be firm yet will yield to gentle pressure.

- Color alone may not tell the whole story, because some avocado like the Hass avocado will turn dark green or black as it ripens, but some other avocado varieties retain their light-green skin even when ripe.

- Avoid fruit with dark blemishes on the skin or over-soft fruit.

- If you plan to serve the fruit in a few days, stock up on hard, unripened fruit.

How to Ripen your Avocados

- The easiest way to ripen an avocado is to place it on your counter or in your fruit bowl for a few days until it gives slightly to gentle squeezing in the palm of your hand.

- To speed up the process of ripening avocados, place the fruit in a plain brown paper bag and store at room temperature 65-75° F until ready to eat (usually two to five days).

- Including an apple or kiwifruit in the bag accelerates the process because these fruits give off natural ethylene gas, which will help ripen your avocados organically. Ethylene is a plant hormone that triggers the ripening process and is used commercially to help ripen bananas, avocados and other fruit. When placed in a paper bag, you are containing the ethylene and encouraging the fruit to ripen faster. For best results, use red or golden delicious apples. These old varieties produce more ethylene than newer varieties (e.g. Gala or Fuji) that have been bred to ripen slowly to maintain their crisp texture, and will be the most effective when it comes to ripening avocados 8.

- Tip: The more apples or kiwifruit you add, the quicker your avocados will ripen !

- Soft ripe fruit can be refrigerated until it is eaten, and should last for at least two more days.

- Refrigerate only ripe or soft avocados.

- Putting your avocado into the oven or microwave is not recommended. The avocado will soften, but it just won’t have the flavor or taste. It will actually taste like unripe avocado (because it is).

If you are cutting into an avocado and there are black spots, vascular bundles (stringiness) or bruises, discard those areas. Vascular bundles (stringiness or stringy avocado fibers running through the avocado pulp) are generally the result of fruit from younger trees, improper storage conditions or transitional times between origins (from one country to the next). Often times the fibers or strings will disappear or become less noticeable as the avocado season goes on and/or trees mature 8.

That being said, it’s very difficult to predict whether your avocados will have strings or not without cutting into them first.

Avocado and Weight Management

The availability and consumption of healthy foods, including vegetables and fruits, is associated with lower weight 9 and body mass index (BMI) 10. Over the last several decades, there has been the general perception that consuming foods rich in fat can lead to weight gain, and low-fat diets would more effectively promote weight control and reduce chronic disease risk 11. However, a key large, randomized, long-term clinical trial found that a moderate fat diet can be an effective part of a weight loss plan and the reduction of chronic disease risk 12. Strong and consistent evidence indicates that dietary patterns that are relatively low in energy density improve weight loss and weight maintenance among adults. Three randomized controlled weight loss trials found that lowering food-based energy density by increasing fruit and/or vegetable intake is associated with significant weight loss 10, 13, 14. The energy density of an entire dietary pattern is estimated by dividing the total amount of calories by the total weight of food consumed; low, medium, and high energy density diets contain 1.3 kcal, 1.7 kcal, and 2.1 kcal per g, respectively 15. Avocados have both a medium energy density of 1.7 kcal/g and a viscose water, dietary fiber and fruit oil matrix that appears to enhance satiety 16. This is consistent with research by Bes-Rastrollo et al. 9, which suggests that avocados support weight control similar to other fruits.

Several preliminary clinical studies suggest that avocados can support weight control. The first trial studied the effect of including one and a half avocados (200 g) in a weight loss diet plan. In this study, sixty-one healthy free-living, overweight, and obese subjects were randomly assigned into either a group consuming 200 g/d of avocados (30.6 g fat) substituted for 30 g of mixed fats, such as margarine and oil, or a control group excluding avocados for 6 weeks 17. Both groups lost similar levels of weight, body mass index (BMI), and percentage of body fat to confirm that avocados can fit into a weight loss diet plan. A randomized single blinded, crossover postprandial study of 26 healthy overweight adults suggested that one-half an avocado consumed at lunch significantly reduced self-reported hunger and desire to eat, and increased satiation as compared to the control meal 16. Additionally, several exploratory trials suggest that monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) rich diets help protect against abdominal fat accumulation and diabetic health complications 18, 19, 20.

Avocado and Cardiovascular Health Benefits

Avocados provide nearly 20 essential nutrients, including a good source of fiber and folate, potassium, Vitamin E, B-vitamins, and folic acid.

Avocados are a potent source of nutrients as well as monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs). According to a recent study, adding an avocado a day to a heart-healthy diet can help improve LDL levels in people who are overweight or obese.

There are eight preliminary avocado cardiovascular clinical trials summarized in Table 3 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 17.

Table 3. Avocado cardiovascular health clinical overview

| Conclusions | Methods | Results | References |

| Daily addition of California avocados to the habitual diet showed a beneficial effect on total cholesterol (TC) and body weight control (Preliminary, uncontrolled study) | – Open label study for 4 weeks (n = 16) – Normal/hypercholesterolemic male patients in Veteran’s Administration Hospital – 27–72 yrs old – 0.5–1.5 California avocados per day in addition to habitual diet | – 1/2 subjects had significantly lowered total cholesterol (TC) by 9–43% – 1/2 subjects had unchanged total cholesterol – No subjects had increased total cholesterol – 3/4 of subjects lost weight or remained weight stable despite an increase intake of calories and fat – Generally the subjects had a more regular bowel movement pattern | Grant 28 |

| An avocado enriched diet was more effective than the American Heart Association Diet in promoting heart healthy lipid profiles in women (Limited number of subjects and short duration) | – Randomized, crossover study for 3 weeks (n = 15) – Females w/ baseline total cholesterol (4–8 mm/L) – 37–58 years old – 66.8 ± 0.8 kg body weight – Two diets: (1) High monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) primarily avocado diet or (2) High in complex carbohydrates low-fat diet (American Heart Association Diet) | – Both diets decreased total cholesterol (TC) compared to baseline – Avocado diets were more effective in decreasing TC 8.2% vs. 4.9% – Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C also called “bad” cholesterol) decreased on avocado enriched diet but not American Heart Association Diet – High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C also called “good” cholesterol) did not change on avocado enriched diet but decreased by 13.9% on the American Heart Association Diet | Colquhoun et al. 29 |

| Avocado enriched diets can help avoid potential adverse effects of low-fat diets on HDL-C and triglycerides (Well designed study but limited number of subjects and short duration) | – Randomized, crossover study for 2 weeks (n = 16) – Healthy subjects baseline total cholesterol 4.2 ± 0.68 mm/L; mean age 26 years; mean BMI 22.9 – Four diets: (1) Control, typical diet (2) Monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) fat diets with avocado (75% from Hass Avocados) (RMF) (3) Habitual diet plus same level of Hass avocados as (2) (FME) (4) Low-saturated diet (LSF) | – Both RMF and LSF diets had similar reductions in total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C also called “bad” cholesterol) – Both habitual diet plus same level of Hass avocados (75% from Hass Avocados) and low-saturated fat diets had significantly lower total cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C – RMF and FME diets lowered triglycerides (TG) and the low-saturated fat diet had significantly increased triglycerides levels | Alvizouri-Munoz et al. 30 |

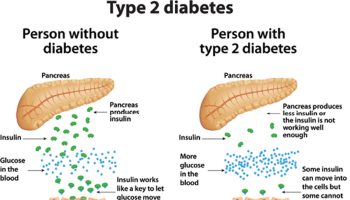

| Partial replacement of avocados for other dietary fats in patients with type 2 diabetes favorably affected serum lipid profile and maintained adequate glycemic control (Well designed study but limited number of subjects) | – Randomized, crossover study for 4 weeks (n = 12) – Women with type 2 diabetes; mean 56 ± 8 years; BMI 28 ± 4 – Three diets (1) Control, American Diabetes Diet plan; 30% kcal from fat (ADA) (2) High MUFA diet with 1 avocado (Hass) and 4 teaspoons of olive oil; 40% kcal from fat (3) High in complex carbohydrates 20% Kcal from fat (High-Carb) | – Both high MUFA and high-Carb diets had a minor hypo-cholesterolemic effect with no changes in HDL-C – High MUFA diet was associated with a greater decrease in triglycerides (20 vs. 7% for High-Carb) – Glycemic control was similar for both High MUFA and High-Carb diets | Lerman-Garber et al. 31 |

| Diets rich in avocados appear to help manage hyper-cholesterolemia (Well designed study but limited number of subjects and level of avocado consumption very high) | – Randomized crossover for study 4 weeks with a controlled diet (n = 16) – Hyper-cholesterolemic subjects with phenotype II and IV dyslipidemias – Two diets: (1) Avocado rich diet (75% fat from avocado) diet (2) Low-saturated fat diet | The Avocado diet had significantly lowered total cholesterol, LDL-C levels, and increased HDL-C with a mild decrease in triglycerides compared the low-saturated fat diet plan | Carranza et al. 32 |

| Avocado-enriched diets had significantly improved lipoprotein and/or triglyceride profiles in normal and hyper-cholesterolemic subjects (Complex clinical design and very short duration) | – Randomized, controlled study for 7 days (n = 67) (1) Healthy normo-lipidemic subjects (< 200 mg/dL) (2) Mild hyper-cholesterolemia and type 2 diabetic patients (201–400 mg/dL)- Enriched avocado diet vs. isocaloric non-avocado diets. 300 g Hass Avocado substituted for other lipid sources (both diets contained about 50% kcal from fat | – Subjects with normal cholesterol had a 16% decrease in serum total cholesterol following avocado diets vs. an increase in total cholesterol with the control (p < 0.001) – Subjects with elevated cholesterol had significant decrease (p < 0.001) total serum cholesterol (17%), LDL-C (22%), triglycerides (22%), and a slight increase in HDL-C – No changes with the non-avocado habitual diet | Lopez-Ledesma et al. 33 |

| Vegetarian diets with avocados promote healthier lipoprotein profiles compared to low-fat and vegetarian diets without avocados (Preliminary study with limited number of subjects) | – Randomized, prospective, transversal and comparative 4 week study and controlled diet (n = 13) – Dyslipidemic subjects with high blood pressure – Three vegetarian diets: (1) 70% carbohydrate, 10% protein and 20% lipids (2) 60% carbohydrates, 10% protein and 30% lipids (75% of the fat from Hass avocados) (3) Diet 2 w/o avocado | The avocado diet significantly reduced LDL-C, whereas high carbohydrate and non-avocado diets did not change LDL-C | Carranza-Madrigal et al. 34 |

| The consumption of as much as 1 1/2 avocados within an energy-restricted diet does not compromise weight loss or lipoproteins or vascular function (Well designed study) | – Randomized, controlled, parallel study, free-living (n = 61) – Male (n = 13) and female (n = 48) adults with a age 40.8 ± 8.9 years; BMI 32 ± 3.9 – Energy restricted diet for 6 weeks at the rate of 30% kcal from fat – 200 g avocado/day (30.6 g fat) substituted for 30 g of mixed fat (e.g., margarine and vegetable oil) compared to a control diet without avocado | – There was no difference in body weight, BMI, and% body fat when avocados were substituted for mixed fats in an energy restricted diet – There was also no difference in serum lipids (total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides), fibrinogen, blood pressure, or blood flow when avocados were substituted for mixed fats in an energy-restricted diet | Pieterse et al. 35 |

The first exploratory avocado clinical study demonstrated that the consumption of 0.5–1.5 avocados per day may help to maintain normal serum total cholesterol in men 21. Half the subjects experienced a 9–43% reduction in serum total cholesterol and the other subjects (either diabetic or very hypercholesterolemic) experienced a neutral effect, but none of the subjects showed increased total cholesterol. Also, the subjects did not gain weight when the avocados were added to their habitual diet.

In the 1990s, a number of avocado clinical trials consistently showed positive effects on blood lipids in a wide variety of diets in studies on healthy, hypercholesterolemic, and type 2 diabetes subjects 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 17. In hypercholesterolemic subjects, avocado enriched diets improved blood lipid profiles by lowering LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides and increasing HDL-cholesterol compared to high carbohydrate diets or other diets without avocado. In normolipidemic subjects, avocado enriched diets improved lipid profiles by lowering LDL-cholesterol without raising triglycerides or lowering HDL-cholesterol. These studies suggest that avocado enriched diets have a positive effect on blood lipids compared to low-fat, high carbohydrate diets or the typical American diet. However, since all these trials were of a small number of subjects (13–37 subjects) and limited duration (1–4 weeks), larger and longer term trials are needed to confirm avocado blood lipid lowering and beyond cholesterol health effects.

In a randomized crossover study of 12 women with type 2 diabetes, a monounsaturated fat diet rich in avocado was compared with a low-fat complex-carbohydrate-rich diet for effects on blood lipids 24. After 4 weeks, the avocado rich diet resulted in significantly lowered plasma triglycerides and both diets maintained similar blood lipids and glycemic controls. Additionally, a preclinical study found that avocados can modify the HDL-C structure by increasing paraoxonase 1 activity, which can enhance lipophilic antioxidant capacity and help convert oxidized LDL-C back to its nonoxidized form 37.

Avocado and Fatty Acids

Avocados can fit into a heart healthy dietary pattern such as the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet plan. Avocados contain a monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA)-rich fruit oil with 71% MUFA, 13% polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), and 16% saturated fatty acids (SFA). As the avocado fruit ripens, the saturated fat decreases and the monounsaturated oleic acid increases 38. The use of avocado dips and spreads as an alternative to more traditional hard, saturated fatty acids rich spreads or dips can assist in lowering dietary saturated fatty acids intake 39.

Table 4. Hass Avocado Spread and Dip Comparison

| Spread and Dip Nutritional Comparison | ||||||

| Fresh Avocado | Butter | Sour Cream | Margarine | Cheddar Cheese | Mayonnaise, Regular | |

| Serving Size | 50g (1/3 of a medium avocado) | 1 Tbsp. | 2 Tbsp. | 1 Tbsp | 1 oz. (1 slice) | 1 Tbsp. |

| Calories | 80 | 100 | 45 | 100 | 110 | 90 |

| Total Fat (g) | 8 | 12 | 4.5 | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| Sat Fat (g) | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1.5 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 0 | 30 | 10 | 0 | 30 | 5 |

| Sodium (mg) | 0 | 90 | 10 | 95 | 180 | 90 |

Footnote: A 50g serving of fresh avocados contain 0mg of cholesterol, 0mg of sodium, 1g saturated fat. Nutritional values are for the item listed only; not as consumed with other foods or ingredients.

[Source Avocado Central. Hass Avocado Spread Comparison 39]Avocado and Dietary Fiber

Avocado fruit carbohydrates are composed of about 80% dietary fiber, consisting of 70% insoluble and 30% soluble fiber 40. Avocados contain 2.0 g and 4.6 g of dietary fiber per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively. Thus, moderate avocado consumption can help to achieve the adequate intake of 14 g dietary fiber per 1000 kcal as about one-third this fiber level can be met by consuming one-half an avocado.

Avocado and Sugars

Compared to other fruits, avocados contain very little sugar. One-half an avocado contains only about 0.2 g sugar (e.g., sucrose, glucose, and fructose). The primary sugar found in avocados is a unique seven-carbon sugar called D-mannoheptulose and its reduced form, perseitol, contributes about 2.0 g per one-half fruit but this is not accounted for as sugar in compositional database as it does not behave nutritionally as conventional sugar and is more of a unique phytochemical to avocados 41, 42. Preliminary D-mannoheptulose research suggests that it may support blood glucose control and weight management 43. The glycemic index and load of an avocado is expected to be about zero due to its very low carbohydrate content.

Avocado and Potassium

Clinical evidence suggests that adequate potassium intake may promote blood pressure control in adults 44. The mean intake of potassium by adults in the United States was approximately 3200 mg per day in men and 2400 mg per day in women, which is lower than the 4700 mg per day recommended intake 45. Avocados contain about 152 mg and 345 mg of potassium per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively. Also, avocados are naturally very low in sodium with just 2 mg and 5.5 mg sodium per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively 2. The health claim for blood pressure identifies foods containing 350 mg potassium and less than 140 mg of sodium per serving as potentially appropriate for this claim.

Avocado and Magnesium

Magnesium acts as a cofactor for many cellular enzymes required in energy metabolism, and it may help support normal vascular tone and insulin sensitivity 46. Preliminary preclinical and clinical researches suggest that low magnesium may play a role in cardiac ischemia 46. In the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, the results suggested that the intake of magnesium had a modest inverse association with risk of coronary heart disease in men 47. Magnesium was shown to inhibit fat absorption to improve postprandial hyperlipidemia in healthy subjects 48. Avocados contain about 9 and 20 mg magnesium per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively 2.

Avocado and Vitamins

- Antioxidant Vitamins

Avocados are one of the few foods that contain significant levels of both vitamins C and E. Vitamin C plays an important role in recycling vitamin E to maintain circulatory antioxidant protection such as potentially slowing the rate of LDL-cholesterol oxidation. Evidence suggests that vitamin C may contribute to vascular health and arterial plaque stabilization 49. According to a recent review article, vitamin C might have greater cardiovascular disease protective effects on specific populations such as smokers, obese, and overweight people; people with elevated cholesterol, hypertension, and type 2 diabetics; and people over 55 years of age 50. Avocado fruit contains 2.6 mg and 6.0 mg vitamin C per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively 2. Avocados contain 0.59 mg and 1.34 mg vitamin E (α-tocopherol) per 30 g and one-half avocado, respectively 2. One randomized clinical study suggested that a combination of vitamin C and E may slow atherosclerotic progression in hypercholesterolemic persons 51.

- Vitamin K1 (phylloquinone)

Vitamin K1 functions as a coenzyme during synthesis of the biologically active form of a number of proteins involved in blood coagulation and bone metabolism 52. Phylloquinone (K1) from plant-based foods is considered to be the primary source of vitamin K in the human diet. Vitamin K1 in its reduced form is a cofactor for the enzymes that facilitate activity for coagulation 53. The amount of vitamin K1 found in avocados is 6.3 μg and 14.3 μg per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively 2. Some people on anticoagulant medications are concerned about vitamin K intake; however, the avocado level of vitamin K1 per ounce is 150 times lower than the 1000 μg of K1 expected to potentially interfere with the anticoagulant effect of drugs such as warfarin (Coumadin) 54, 55.

- B-vitamins

Deficiencies in B-vitamins such as folate and B-6 may increase homocysteine levels, which could reduce vascular endothelial health and increase cardiovascular disease risk 56. Avocados contain 27 μg folate and 0.09 mg vitamin B-6 per 30 g and 61 μg folate, respectively, and 0.20 mg vitamin B-6 per one-half fruit 2.

Avocado and Phytochemicals

- Carotenoids

The primary avocado carotenoids are a subclass known as xanthophylls, oxygen-containing fat-soluble antioxidants 57 (Table 1). Xanthophylls, such as lutein, are more polar than carotenes (the other carotenoid subclasses including β-carotene), so they have a much lower propensity for pro-oxidant activity 58. Avocados have the highest lipophilic total antioxidant capacity among fruits and vegetables 59. In a relatively healthy population, the DASH diet pattern clinical study reported reduced oxidative stress (blood ORAC and urinary isoprostanes) compared to a typical American diet 60, which appears primarily due to the DASH diet providing significantly more serum carotenoids, especially the xanthophyll carotenoids lutein, β-cryptoxanthin, and zeaxanthin, as a result of increased fruit and vegetable consumption. Xanthophylls appear to reduce circulating oxidized LDL-C, a preliminary biomarker for the initiation and progression of vascular damage 61. The Los Angeles Atherosclerosis Study, a prospective study, findings suggest that higher levels of plasma xanthophylls were inversely related to the progression of carotid intima-media thickness, which may be protective against early atherosclerosis 62. Although this research is encouraging, more clinical studies are needed to understand the cardiovascular health benefits associated with avocado carotenoids.

The consumption of avocados can be an important dietary source of xanthophyll carotenoids 38. Hass avocado carotenoid levels tend to significantly increase as the harvest season progresses from January to September 38. In Hass avocados, xanthophylls lutein and cryptoxanthin predominate over the carotenes, contributing about 90% of the total carotenoids 38. USDA reports lutein and zeaxanthin at 81 μg and 185 μg per 30 g and one half fruit, respectively, and cryptoxanthin at 44 μg and 100 μg per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively 2. However, a more comprehensive analysis of avocados including xanthophylls has found much higher levels ranging from 350–500 μg per 30 g to 800–1100 μg per one-half fruit at time of harvest 38. The color of avocado flesh varies from dark green just under the skin to pale green in the middle section of the flesh to yellow near the seed 38. The total carotenoid concentrations were found to be greatest in the dark green flesh close to peel 63.

The intestinal absorption of carotenoids depends on the presence of dietary fat to solubilize and release carotenoids for transfer into the gastrointestinal fat micelle and then the circulatory system 64, 65. Avocado fruit has a unique unsaturated oil and water matrix naturally designed to enhance carotenoid absorption. For salads, a significant source of carotenoids, reduced fat or fat free salad dressings are common in the marketplace and these dressings have been shown to significantly reduce carotenoid absorption compared to full fat dressings 66. Similar clinical research has demonstrated that adding avocado to salad without dressing, or with reduced fat/fat free dressing and serving avocados with salsa increases carotenoid bioavailability by 2–5 times 67.

- Phenolics

Preliminary evidence suggests beneficial effects of fruit phenolics on reducing cardiovascular disease risk by reducing oxidative and inflammatory stress, enhancing blood flow and arterial endothelial health, and inhibiting platelet aggregation to help maintain vascular health 68, 69, 70, 71. Avocados contain a moderate level of phenolic compounds contributing 60 mg and 140 mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 30 g and one-half fruit, respectively. The avocado also has a total antioxidant capacity of 600 μmol Trolox Equilvalent (TE) per 30 g or 1350 μmol TE per one-half fruit 72. This places avocados in the mid-range of fruit phenolic levels. Avocados have the highest fruit lipophilic antioxidant capacity, which may be one factor in helping to reduce serum lipid peroxidation and promoting vascular health 72.

- Phytosterols

Avocados are the richest known fruit source of phytosterols 73 with about 26 mg and 57 mg per 30 g and one half fruit, respectively 2. Other fruits contain substantially less phytosterols at about 3 mg per serving 73. Although the avocado’s phytosterol content is lower than that of fortified foods and dietary supplements, its unique emulsified fat matrix and natural phytosterol glycosides may help promote stronger intestinal cholesterol blocking activity than fortified foods and supplements 74. A recent economic valuation in Canada of the potential health benefits from foods with phytosterols suggests that they may play a role in enhancing cardiovascular health and reducing associated health costs 75.

Avovcado and Healthy Aging

- DNA Damage Protection

Several clinical studies suggest that xanthophylls, similar to those found in avocados, may have antioxidant and DNA protective effects with possible healthy aging protective effects. One study was conducted involving 82 male airline pilots and frequent air travelers who are exposed to high levels of cosmic ionizing radiation known to damage DNA, potentially accelerating the aging process 76. There was a significant and inverse association between intake of vitamin C, beta-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and lutein-zeaxanthin from fruits and vegetables and the frequency of chromosome translocation, a biomarker of cumulative DNA damage. In another trial, lipid peroxidation (8-epiprostaglandin F2a) was correlated inversely with plasma xanthophyll levels 77. In other studies, inverse correlations were found between lutein and oxidative DNA damage as measured by the comet assay, and in contrast to beta-carotene 78, 79. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey analysis suggests that xanthophylls intake decreases with aging 80.

- Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is characterized by progressive deterioration of joint cartilage and function with associated impairment, and this affects most people as they age or become overweight or obese 81, 82. This joint deterioration may be triggered by oxidative and inflammation stress, which can cause an imbalance in biosynthesis and degradation of the joint extracellular matrix leading to loss of function 81. A cross-sectional study reported that fruits and vegetables rich in lutein and zeaxanthin (the primary carotenoids in avocados) are associated with decreased risk of cartilage defects (early indicator of osteoarthritis) 83.

Avocado and soy unsaponifiables (ASU) is a mixture of fat soluble extracts in a ratio of about 1(avocado):2(soy). The major components of avocado and soy unsaponifiables (ASU) are considered anti-inflammatory compounds with both antioxidant and analgesic activities 81, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89. In vitro studies found that pretreatment of chondrocytes with avocado and soy unsaponifiables blocked the activation of COX-2 transcripts and secretion of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) to baseline levels after activation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Further study revealed that avocado and soy unsaponifiables can also block tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1β, and iNOS expression to levels similar to those in nonactivated control cultures. Additional laboratory studies suggest that avocado and soy unsaponifiables (ASU) may facilitate repair of osteoarthritis cartilage through its effect on osteoblasts 81.

Clinical support for avocado and soy unsaponifiables in the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis comes from four randomized controlled trials 90, 91, 92, 89 and one meta-analysis 93. All studies used 300 mg per day. The clinical trials were generally positive with three providing osteoarthritis support and one study showing no joint cartilage improvement compared to placebo.

- Eye Health

Lutein and zeaxanthin are selectively taken up into the macula of the eye (the portion of the eye where light is focused on the lens) 94. Relative intakes of lutein and zeaxanthin decrease with age and the levels are lower in females than males 80. Mexican Americans have the highest intake of lutein and zeaxanthin than any other ethnicity and they are among the highest consumers of avocados in the United States. Observational studies show that low dietary intake and plasma concentration of lutein may increase age-related eye dysfunction 95. Research from the Women’s Health Initiative Observation Study found that MUFA rich diets were protective of age-related eye dysfunction 96, 97. Avocados may contribute to eye health since they contain a combination of MUFA and lutein/zeaxanthin and help improve carotenoid absorption from other fruits and vegetables 67. Avocados contain 185 μg of lutein/zeaxanthin per one-half fruit, which is expected to be more highly bioavailable than most other fruit and vegetable sources.

- Skin Health

Skin often shows the first visible indication of aging. Topical application or consumption of some fruits and vegetables or their extracts such as avocado has been recommended for skin health 98. The facial skin is frequently subjected to ongoing oxidative and inflammatory damage by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) and visible radiation and carotenoids may be able to combat this damage. A clinical study found that the concentration of carotenoids in the skin is directly related to the level of fruit and vegetable intake 99. Avocado’s highly bioavailable lutein and zeaxanthin may help to protect the skin from damage from both UV and visible radiation 98. Several small studies suggest that topical or oral lutein can provide photo-protective activity 100, 101, 102.

A cross-sectional study examined the relationship between skin anti-aging and diet choices in 716 Japanese women 103. After controlling for covariates including age, smoking status, BMI, and lifetime sun exposure, the results showed that higher intakes of total dietary fat were significantly associated with more skin elasticity. A higher intake of green and yellow vegetables was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles 103. Several preclinical studies suggest that avocado components may protect skin health by enhancing wound healing activity and reducing UV damage 103, 104.

- Cancer

Avocados contain a number of bioactive phytochemicals including carotenoids, terpenoids, D-mannoheptulose, persenone A and B, phenols, and glutathione that have been reported to have anti-carcinogenic properties 105. The concentrations of some of these phytochemicals in the avocado may be potentially efficacious (Jones et al., 1992). Currently, direct avocado anti-cancer activity is very preliminary with all data based on in vitro studies on human cancer cell lines.

Cancer of the larynx, pharynx, and oral cavity are the primary area of avocado cancer investigation. Glutathione, a tripeptide composed of three amino acids (glutamic acid, cysteine, and glycine) functions as an antioxidant 106. The National Cancer Institute found that avocado’s glutathione levels of 8.4 mg per 30 g or 19 mg per one-half fruit is several fold higher than that of other fruits 106. Even though the body digests glutathione down to individual amino acids when foods are consumed, a large population-based case controlled study showed a significant correlation between increased glutathione intakes and decreased risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer 107. One clinical study found that plasma lutein and total xanthophylls but not individual carotenes or total carotenes reduced biomarkers of oxidative stress (urinary concentrations of both total F2-isoprostanes and 8-epi-prostaglandin) in patients with early-stage (in situ, stage I, or stage II) cancer of larynx, pharynx, or oral cavity 78. Xanthophyll rich avocado extracts have been shown in preclinical studies to have anti-Helicobacter pylori activity for a potential effect on gastritis ulcers, which may be associated with gastric cancer risk.

Dietary carotenoids show potential breast cancer protective biological activities, including antioxidant activity, induction of apoptosis, and inhibition of mammary cell proliferation 79. Studies examining the role of fruits and vegetables and carotenoid consumption in relation to breast cancer recurrence are limited and report mixed results 79. In preclinical studies, total carotenoids and lutein appear to reduce oxidative stress, a potential trigger for breast cancer 108. In women previously treated for breast cancer, a significant inverse association was found between total plasma carotenoid concentrations and oxidative stress 79, but more clinical research is needed to confirm this finding.

Mammographic density is one of the strongest predictors of breast cancer risk 109. The association between carotenoids and breast cancer risk as a function of mammographic density was conducted in a nested, case-control study consisting of 604 breast cancer cases and 626 controls with prospectively measured circulating carotenoid levels and mammographic density in the Nurses’ Health Study 109. Overall, circulating total carotenoids were inversely associated with breast cancer risk. Among women in the highest tertile of mammographic density, elevated levels α-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and lutein/zeaxanthin in the blood were associated with a 40–50% reduction in breast cancer risk . In contrast, there was no inverse association between carotenoids and breast cancer risk among women with low-mammographic density. These results suggest that plasma levels of carotenoids may play a role in reducing breast cancer risk, particularly among women with high mammographic density. There are no direct avocado breast cancer clinical studies.

Exploratory studies in prostate cancer cell lines suggest antiproliferative and antitumor effects of avocado lipid extracts 63. Lutein is one of the active components identified. There are currently no human studies to confirm this potential lutein and prostate cancer relationship.

References- California Avocado Commission. California Avocado history. 2012. https://www.californiaavocado.com/

- United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service. USDA Food Composition Databases. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/

- Fulgoni V. L., Dreher M. L., Davenport A. J. Consumption of avocados in diets of US adults: NHANES 2011-2006. Boston, MA: American Dietetic Association; 2010a. Abstract #54.

- USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) Avocado, almond, pistachio and walnut Composition. Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 24. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2011.

- Unlu NZ, Bohn T, Clinton SK, Schwartz SJ. Carotenoid absorption from salad and salsa by humans is enhanced by the addition of avocado or avocado oil. J Nutr. 2005 Mar;135(3):431-6. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.431

- Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam RM, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL, Hu FB. Prospective study of dietary energy density and weight gain in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Sep;88(3):769-77. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.3.769

- Fulgoni V. L., Dreher M. L., Davenport A. J. Avocado consumption associated with better nutrient intake and better health indices in US adults: NHANES 2011-2006. Experimental Biology. 2010b. Abstract #8514. Anaheim, CA.

- California Avocado Commission. How to Ripen an Avocado – the Definitive Guide. https://www.californiaavocado.com/blog/how-to-ripen-an-avocado

- Prospective study of dietary energy density and weight gain in women. Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam RM, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL, Hu FB. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Sep; 88(3):769-77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18779295/

- A low-energy-dense diet adding fruit reduces weight and energy intake in women. de Oliveira MC, Sichieri R, Venturim Mozzer R. Appetite. 2008 Sep; 51(2):291-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18439712/

- Is a low fat diet the optimal way to cut energy intake over the long-term in overweight people? Walker KZ, O’Dea K. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2001 Aug; 11(4):244-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11831109/

- Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Smith SR, Ryan DH, Anton SD, McManus K, Champagne CM, Bishop LM, Laranjo N, Leboff MS, Rood JC, de Jonge L, Greenway FL, Loria CM, Obarzanek E, Williamson DA. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 26; 360(9):859-73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357/

- The impact of a long-term reduction in dietary energy density on body weight within a randomized diet trial. Saquib N, Natarajan L, Rock CL, Flatt SW, Madlensky L, Kealey S, Pierce JP. Nutr Cancer. 2008; 60(1):31-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18444133/

- Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Jun; 85(6):1465-77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17556681/

- Dietary energy density predicts women’s weight change over 6 y. Savage JS, Marini M, Birch LL. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Sep; 88(3):677-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18779283/

- Wien M., Haddad E., Sabate′ J. Effect of incorporating avocado in meals on satiety in healthy overweight adults. 2011. 11th European Nutrition Conference of the Federation of the European Nutrition Societies. October, 27. Madrid, Spain.

- Substitution of high monounsaturated fatty acid avocado for mixed dietary fats during an energy-restricted diet: effects on weight loss, serum lipids, fibrinogen, and vascular function. Pieterse Z, Jerling JC, Oosthuizen W, Kruger HS, Hanekom SM, Smuts CM, Schutte AE. Nutrition. 2005 Jan; 21(1):67-75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15661480/

- Differential effects of two isoenergetic meals rich in saturated or monounsaturated fat on endothelial function in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Tentolouris N, Arapostathi C, Perrea D, Kyriaki D, Revenas C, Katsilambros N. Diabetes Care. 2008 Dec; 31(12):2276-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18835957/

- Monounsaturated fat-rich diet prevents central body fat distribution and decreases postprandial adiponectin expression induced by a carbohydrate-rich diet in insulin-resistant subjects. Paniagua JA, Gallego de la Sacristana A, Romero I, Vidal-Puig A, Latre JM, Sanchez E, Perez-Martinez P, Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Jimenez F. Diabetes Care. 2007 Jul; 30(7):1717-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17384344/

- A MUFA-rich diet improves posprandial glucose, lipid and GLP-1 responses in insulin-resistant subjects. Paniagua JA, de la Sacristana AG, Sánchez E, Romero I, Vidal-Puig A, Berral FJ, Escribano A, Moyano MJ, Peréz-Martinez P, López-Miranda J, Pérez-Jiménez F. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007 Oct; 26(5):434-44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17914131/

- Influence of avocados on serum cholesterol. GRANT WC. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960 May; 104:45-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13828982/

- Comparison of the effects on lipoproteins and apolipoproteins of a diet high in monounsaturated fatty acids, enriched with avocado, and a high-carbohydrate diet. Colquhoun DM, Moores D, Somerset SM, Humphries JA. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Oct; 56(4):671-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1414966/

- Effects of avocado as a source of monounsaturated fatty acids on plasma lipid levels. Alvizouri-Muñoz M, Carranza-Madrigal J, Herrera-Abarca JE, Chávez-Carbajal F, Amezcua-Gastelum JL. Arch Med Res. 1992 Winter; 23(4):163-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1308699/

- Effect of a high-monounsaturated fat diet enriched with avocado in NIDDM patients. Lerman-Garber I, Ichazo-Cerro S, Zamora-González J, Cardoso-Saldaña G, Posadas-Romero C. Diabetes Care. 1994 Apr; 17(4):311-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8026287/

- Effects of avocado on the level of blood lipids in patients with phenotype II and IV dyslipidemias. Carranza J, Alvizouri M, Alvarado MR, Chávez F, Gómez M, Herrera JE. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex. 1995 Jul-Aug; 65(4):342-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8561655/

- Monounsaturated fatty acid (avocado) rich diet for mild hypercholesterolemia. López Ledesma R, Frati Munari AC, Hernández Domínguez BC, Cervantes Montalvo S, Hernández Luna MH, Juárez C, Morán Lira S. Arch Med Res. 1996 Winter; 27(4):519-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8987188/

- Effects of a vegetarian diet vs. a vegetarian diet enriched with avocado in hypercholesterolemic patients. Carranza-Madrigal J, Herrera-Abarca JE, Alvizouri-Muñoz M, Alvarado-Jimenez MR, Chavez-Carbajal F. Arch Med Res. 1997 Winter; 28(4):537-41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9428580/

- GRANT WC. Influence of avocados on serum cholesterol. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960 May;104:45-7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-104-25722

- Colquhoun DM, Moores D, Somerset SM, Humphries JA. Comparison of the effects on lipoproteins and apolipoproteins of a diet high in monounsaturated fatty acids, enriched with avocado, and a high-carbohydrate diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Oct;56(4):671-7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.4.671

- Alvizouri-Muñoz M, Carranza-Madrigal J, Herrera-Abarca JE, Chávez-Carbajal F, Amezcua-Gastelum JL. Effects of avocado as a source of monounsaturated fatty acids on plasma lipid levels. Arch Med Res. 1992 Winter;23(4):163-7.

- Lerman-Garber I, Ichazo-Cerro S, Zamora-González J, Cardoso-Saldaña G, Posadas-Romero C. Effect of a high-monounsaturated fat diet enriched with avocado in NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. 1994 Apr;17(4):311-5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.4.311

- Carranza J, Alvizouri M, Alvarado MR, Chávez F, Gómez M, Herrera JE. Efectos del aguacate sobre los niveles de lípidos séricos en pacientes con dislipidemias fenotipo II y IV [Effects of avocado on the level of blood lipids in patients with phenotype II and IV dyslipidemias]. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex. 1995 Jul-Aug;65(4):342-8. Spanish.

- López Ledesma R, Frati Munari AC, Hernández Domínguez BC, Cervantes Montalvo S, Hernández Luna MH, Juárez C, Morán Lira S. Monounsaturated fatty acid (avocado) rich diet for mild hypercholesterolemia. Arch Med Res. 1996 Winter;27(4):519-23.

- Carranza-Madrigal J, Herrera-Abarca JE, Alvizouri-Muñoz M, Alvarado-Jimenez MR, Chavez-Carbajal F. Effects of a vegetarian diet vs. a vegetarian diet enriched with avocado in hypercholesterolemic patients. Arch Med Res. 1997 Winter;28(4):537-41.

- Pieterse Z, Jerling JC, Oosthuizen W, Kruger HS, Hanekom SM, Smuts CM, Schutte AE. Substitution of high monounsaturated fatty acid avocado for mixed dietary fats during an energy-restricted diet: effects on weight loss, serum lipids, fibrinogen, and vascular function. Nutrition. 2005 Jan;21(1):67-75. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.09.010

- Dreher ML, Davenport AJ. Hass Avocado Composition and Potential Health Effects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2013;53(7):738-750. doi:10.1080/10408398.2011.556759. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3664913/

- High-density lipoproteins (HDL) size and composition are modified in the rat by a diet supplemented with “Hass” avocado (Persea americana Miller). Pérez Méndez O, García Hernández L. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2007 Jan-Mar; 77(1):17-24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17500188/

- California Hass avocado: profiling of carotenoids, tocopherol, fatty acid, and fat content during maturation and from different growing areas. Lu QY, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang D, Lee RP, Gao K, Byrns R, Heber D. J Agric Food Chem. 2009 Nov 11; 57(21):10408-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19813713/

- Avocado Central. Hass Avocado Spread Comparison: Spread on Nutrition with Hass Avocados. 2010. https://www.avocadocentral.com/nutrition/avocado-spread-comparison

- Database and quick methods of assessing typical dietary fiber intakes using data for 228 commonly consumed foods. Marlett JA, Cheung TF. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997 Oct; 97(10):1139-48, 1151; quiz 1149-50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9336561/

- Development of a rapid method for the sequential extraction and subsequent quantification of fatty acids and sugars from avocado mesocarp tissue. Meyer MD, Terry LA. J Agric Food Chem. 2008 Aug 27; 56(16):7439-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18680299/

- High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of D-manno-heptulose, perseitol, glucose, and fructose in avocado cultivars. Shaw PE, Wilson CW 3rd, Knight RJ Jr. J Agric Food Chem. 1980 Mar-Apr; 28(2):379-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7391374/

- Roth G. Mannoheptulose glycolytic inhibitor and novel calorie restriction mimetic. 2009. Experimental Biology. Abstract # 553.1. New Orleans, LA.

- American Heart Association. How Potassium Can Help Control High Blood Pressure. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/PreventionTreatmentofHighBloodPressure/Potassium-and-High-Blood-Pressure_UCM_303243_Article.jsp

- American Heart Association. A Primer on Potassium. https://sodiumbreakup.heart.org/a_primer_on_potassium

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) Chapter 6. Magnesium. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D and Fluoride; pp. 186–255.

- Magnesium intake and risk of coronary heart disease among men. Al-Delaimy WK, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004 Feb; 23(1):63-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14963055/

- Effects of magnesium on postprandial serum lipid responses in healthy human subjects. Kishimoto Y, Tani M, Uto-Kondo H, Saita E, Iizuka M, Sone H, Yokota K, Kondo K. Br J Nutr. 2010 Feb; 103(4):469-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19941679/

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) Chapter 5. Vitamin C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium and Carotenoids; pp. 95–122.

- Vitamins and cardiovascular disease. Honarbakhsh S, Schachter M. Br J Nutr. 2009 Apr; 101(8):1113-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18826726/

- Six-year effect of combined vitamin C and E supplementation on atherosclerotic progression: the Antioxidant Supplementation in Atherosclerosis Prevention (ASAP) Study. Salonen RM, Nyyssönen K, Kaikkonen J, Porkkala-Sarataho E, Voutilainen S, Rissanen TH, Tuomainen TP, Valkonen VP, Ristonmaa U, Lakka HM, Vanharanta M, Salonen JT, Poulsen HE, Antioxidant Supplementation in Atherosclerosis Prevention Study.. Circulation. 2003 Feb 25; 107(7):947-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12600905/

- Dietary reference intakes: vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Trumbo P, Yates AA, Schlicker S, Poos M. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001 Mar; 101(3):294-301. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11269606/

- Vitamin K, an example of triage theory: is micronutrient inadequacy linked to diseases of aging? McCann JC, Ames BN. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Oct; 90(4):889-907. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19692494/

- Low-dose oral vitamin K reliably reverses over-anticoagulation due to warfarin. Crowther MA, Donovan D, Harrison L, McGinnis J, Ginsberg J. Thromb Haemost. 1998 Jun; 79(6):1116-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9657434/

- Vitamin K content of nuts and fruits in the US diet. Dismore ML, Haytowitz DB, Gebhardt SE, Peterson JW, Booth SL. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003 Dec; 103(12):1650-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14647095/

- Homocysteine and coronary atherosclerosis: from folate fortification to the recent clinical trials. Antoniades C, Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D, Marinou K, Stefanadis C. Eur Heart J. 2009 Jan; 30(1):6-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19029125/

- Carotenoids and cardiovascular health. Voutilainen S, Nurmi T, Mursu J, Rissanen TH. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Jun; 83(6):1265-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16762935/

- Biologic activity of carotenoids related to distinct membrane physicochemical interactions. McNulty H, Jacob RF, Mason RP. Am J Cardiol. 2008 May 22; 101(10A):20D-29D. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18474269/

- Lipophilic and hydrophilic antioxidant capacities of common foods in the United States. Wu X, Beecher GR, Holden JM, Haytowitz DB, Gebhardt SE, Prior RL. J Agric Food Chem. 2004 Jun 16; 52(12):4026-37. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15186133/

- A dietary pattern that lowers oxidative stress increases antibodies to oxidized LDL: results from a randomized controlled feeding study. Miller ER 3rd, Erlinger TP, Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Charleston J, Lin PH, Appel LJ. Atherosclerosis. 2005 Nov; 183(1):175-82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16216596/

- Relationships of circulating carotenoid concentrations with several markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA)/Young Adult Longitudinal Trends in Antioxidants (YALTA) study. Hozawa A, Jacobs DR Jr, Steffes MW, Gross MD, Steffen LM, Lee DH. Clin Chem. 2007 Mar; 53(3):447-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17234732/

- Oxygenated carotenoid lutein and progression of early atherosclerosis: the Los Angeles atherosclerosis study. Dwyer JH, Navab M, Dwyer KM, Hassan K, Sun P, Shircore A, Hama-Levy S, Hough G, Wang X, Drake T, Merz CN, Fogelman AM. Circulation. 2001 Jun 19; 103(24):2922-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11413081/

- Inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth by an avocado extract: role of lipid-soluble bioactive substances. Lu QY, Arteaga JR, Zhang Q, Huerta S, Go VL, Heber D. J Nutr Biochem. 2005 Jan; 16(1):23-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15629237/

- Differential effect of dietary antioxidant classes (carotenoids, polyphenols, vitamins C and E) on lutein absorption. Reboul E, Thap S, Tourniaire F, André M, Juhel C, Morange S, Amiot MJ, Lairon D, Borel P. Br J Nutr. 2007 Mar; 97(3):440-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17313704/

- Pigments in avocado tissue and oil. Ashton OB, Wong M, McGhie TK, Vather R, Wang Y, Requejo-Jackman C, Ramankutty P, Woolf AB. J Agric Food Chem. 2006 Dec 27; 54(26):10151-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17177553/

- Carotenoid bioavailability is higher from salads ingested with full-fat than with fat-reduced salad dressings as measured with electrochemical detection. Brown MJ, Ferruzzi MG, Nguyen ML, Cooper DA, Eldridge AL, Schwartz SJ, White WS. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Aug; 80(2):396-403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15277161/

- Carotenoid absorption from salad and salsa by humans is enhanced by the addition of avocado or avocado oil. Unlu NZ, Bohn T, Clinton SK, Schwartz SJ. J Nutr. 2005 Mar; 135(3):431-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15735074/

- Fruit polyphenols and CVD risk: a review of human intervention studies. Chong MF, Macdonald R, Lovegrove JA. Br J Nutr. 2010 Oct; 104 Suppl 3():S28-39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20955648/

- Polyphenols and disease risk in epidemiologic studies. Arts IC, Hollman PC. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jan; 81(1 Suppl):317S-325S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15640497/

- Vascular action of polyphenols. Ghosh D, Scheepens A. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009 Mar; 53(3):322-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19051188/

- Oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Victor VM, Rocha M, Solá E, Bañuls C, Garcia-Malpartida K, Hernández-Mijares A. Curr Pharm Des. 2009; 15(26):2988-3002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19754375/

- Wu X., Gu L., Holden J., Haytowitz D. B., Gebhardt S. E., Beecher G. R., Prior R. L. Development of a database for total antioxidant capacity in foods: A preliminary study. J. Food. Comp. Anal. 2007;17:407–422.

- Avocado fruit is a rich source of beta-sitosterol. Duester KC. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001 Apr; 101(4):404-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11320941/

- Phytosterol glycosides reduce cholesterol absorption in humans. Lin X, Ma L, Racette SB, Anderson Spearie CL, Ostlund RE Jr. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009 Apr; 296(4):G931-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246636/

- Economic valuation of the potential health benefits from foods enriched with plant sterols in Canada. Gyles CL, Carlberg JG, Gustafson J, Davlut DA, Jones PJ. Food Nutr Res. 2010 Oct 7; 54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20941328/

- High dietary antioxidant intakes are associated with decreased chromosome translocation frequency in airline pilots. Yong LC, Petersen MR, Sigurdson AJ, Sampson LA, Ward EM. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Nov; 90(5):1402-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19793852/

- Plasma xanthophyll carotenoids correlate inversely with indices of oxidative DNA damage and lipid peroxidation. Haegele AD, Gillette C, O’Neill C, Wolfe P, Heimendinger J, Sedlacek S, Thompson HJ. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000 Apr; 9(4):421-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10794487/

- Plasma Carotenoids and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Patients with prior Head and Neck Cancer. Hughes KJ, Mayne ST, Blumberg JB, Ribaya-Mercado JD, Johnson EJ, Cartmel B. Biomark Insights. 2009 Mar 23; 4():17-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19554200/

- Plasma and dietary carotenoids are associated with reduced oxidative stress in women previously treated for breast cancer. Thomson CA, Stendell-Hollis NR, Rock CL, Cussler EC, Flatt SW, Pierce JP. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007 Oct; 16(10):2008-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17932348/

- Intake of lutein and zeaxanthin differ with age, sex, and ethnicity. Johnson EJ, Maras JE, Rasmussen HM, Tucker KL. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Sep; 110(9):1357-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20800129/

- A potential role for avocado- and soybean-based nutritional supplements in the management of osteoarthritis: a review. DiNubile NA. Phys Sportsmed. 2010 Jun; 38(2):71-81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20631466/

- Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH, National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Jan; 58(1):15-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18163481/

- Effect of dietary lutein and zeaxanthin on plasma carotenoids and their transport in lipoproteins in age-related macular degeneration. Wang W, Connor SL, Johnson EJ, Klein ML, Hughes S, Connor WE. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Mar; 85(3):762-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17344498/

- Metabolic effects of avocado/soy unsaponifiables on articular chondrocytes. Lippiello L, Nardo JV, Harlan R, Chiou T. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008 Jun; 5(2):191-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18604259/

- Avocado soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) suppress TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, COX-2, iNOS gene expression, and prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide production in articular chondrocytes and monocyte/macrophages. Au RY, Al-Talib TK, Au AY, Phan PV, Frondoza CG. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007 Nov; 15(11):1249-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17845860/

- Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables prevent the inhibitory effect of osteoarthritic subchondral osteoblasts on aggrecan and type II collagen synthesis by chondrocytes. Henrotin YE, Deberg MA, Crielaard JM, Piccardi N, Msika P, Sanchez C. J Rheumatol. 2006 Aug; 33(8):1668-78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16832844/

- Signaling transduction: target in osteoarthritis. Berenbaum F. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004 Sep; 16(5):616-22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15314504/

- Avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) for osteoarthritis – a systematic review. Ernst E. Clin Rheumatol. 2003 Oct; 22(4-5):285-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14576991/

- Efficacy and safety of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in the treatment of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee and hip. A prospective, multicenter, three-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Blotman F, Maheu E, Wulwik A, Caspard H, Lopez A. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997 Dec; 64(12):825-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9476272/

- Structural effect of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables on joint space loss in osteoarthritis of the hip. Lequesne M, Maheu E, Cadet C, Dreiser RL. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Feb; 47(1):50-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11932878/

- Symptoms modifying effect of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) in knee osteoarthritis. A double blind, prospective, placebo-controlled study. Appelboom T, Schuermans J, Verbruggen G, Henrotin Y, Reginster JY. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001; 30(4):242-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11578021/

- Symptomatic efficacy of avocado/soybean unsaponifiables in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee and hip: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial with a six-month treatment period and a two-month followup demonstrating a persistent effect. Maheu E, Mazières B, Valat JP, Loyau G, Le Loët X, Bourgeois P, Grouin JM, Rozenberg S. Arthritis Rheum. 1998 Jan; 41(1):81-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9433873/

- Symptomatic efficacy of avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) in osteoarthritis (OA) patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008 Apr; 16(4):399-408. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18042410/

- Associations between lutein, zeaxanthin, and age-related macular degeneration: an overview. Carpentier S, Knaus M, Suh M. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2009 Apr; 49(4):313-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19234943/

- Association between dietary fat intake and age-related macular degeneration in the Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study (CAREDS): an ancillary study of the Women’s Health Initiative. Parekh N, Voland RP, Moeller SM, Blodi BA, Ritenbaugh C, Chappell RJ, Wallace RB, Mares JA, CAREDS Research Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov; 127(11):1483-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19901214/

- Fat consumption and its association with age-related macular degeneration. Chong EW, Robman LD, Simpson JA, Hodge AM, Aung KZ, Dolphin TK, English DR, Giles GG, Guymer RH. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009 May; 127(5):674-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19433719/

- Associations between age-related nuclear cataract and lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum in the Carotenoids in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an Ancillary Study of the Women’s Health Initiative. Moeller SM, Voland R, Tinker L, Blodi BA, Klein ML, Gehrs KM, Johnson EJ, Snodderly DM, Wallace RB, Chappell RJ, Parekh N, Ritenbaugh C, Mares JA, CAREDS Study Group., Women’s Helath Initiative. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar; 126(3):354-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18332316/

- Lutein and zeaxanthin in eye and skin health. Roberts RL, Green J, Lewis B. Clin Dermatol. 2009 Mar-Apr; 27(2):195-201. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19168000/

- Effect of fruit and vegetable intake on skin carotenoid detected by non-invasive Raman spectroscopy. Rerksuppaphol S, Rerksuppaphol L. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006 Aug; 89(8):1206-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17048431/

- Skin aging. Puizina-Ivić N. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008 Jun; 17(2):47-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18709289/

- Beneficial long-term effects of combined oral/topical antioxidant treatment with the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin on human skin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Palombo P, Fabrizi G, Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Fluhr J, Roberts R, Morganti P. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007; 20(4):199-210. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17446716/

- Role of topical and nutritional supplement to modify the oxidative stress. Morganti P, Bruno C, Guarneri F, Cardillo A, Del Ciotto P, Valenzano F. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2002 Dec; 24(6):331-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18494887/

- Association of dietary fat, vegetables and antioxidant micronutrients with skin ageing in Japanese women. Nagata C, Nakamura K, Wada K, Oba S, Hayashi M, Takeda N, Yasuda K. Br J Nutr. 2010 May; 103(10):1493-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20085665/

- Polyhydroxylated fatty alcohols derived from avocado suppress inflammatory response and provide non-sunscreen protection against UV-induced damage in skin cells. Rosenblat G, Meretski S, Segal J, Tarshis M, Schroeder A, Zanin-Zhorov A, Lion G, Ingber A, Hochberg M. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011 May; 303(4):239-46. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20978772/

- Selective induction of apoptosis of human oral cancer cell lines by avocado extracts via a ROS-mediated mechanism. Ding H, Han C, Guo D, Chin YW, Ding Y, Kinghorn AD, D’Ambrosio SM. Nutr Cancer. 2009; 61(3):348-56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19373608/

- Dietary glutathione intake and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Flagg EW, Coates RJ, Jones DP, Byers TE, Greenberg RS, Gridley G, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Haber M, Preston-Martin S. Am J Epidemiol. 1994 Mar 1; 139(5):453-65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8154469/

- Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for gastrointestinal disorders. Castillo-Juárez I, González V, Jaime-Aguilar H, Martínez G, Linares E, Bye R, Romero I. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009 Mar 18; 122(2):402-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19162157/

- Chemopreventive characteristics of avocado fruit. Ding H, Chin YW, Kinghorn AD, D’Ambrosio SM. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007 Oct; 17(5):386-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17582784/

- Circulating carotenoids, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer. Tamimi RM, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Cancer Res. 2009 Dec 15; 69(24):9323-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19934322/