What are Healthy Exercises

The Department of Health and Human Services recommends these exercise guidelines for most healthy adults:

- AEROBIC activity. Get at least 150 minutes a week of moderate aerobic activity — such as brisk walking, swimming or mowing the lawn — or 75 minutes a week of vigorous aerobic activity — such as running or aerobic dancing. You can also do a combination of moderate and vigorous activity. It’s best to do this over the course of a week.

- STRENGTH training. Strength train at least twice a week. Consider free weights, weight machines or activities that use your own body weight — such as rock climbing or heavy gardening. The amount of time for each session is up to you.

Five Amazing Things Aerobic Exercise Can Do for You

- Aerobic exercise rebuilds and strengthens your aerobic base, the system that brings fuel and oxygen to the teeny engines (the mitochondria) in your muscles where they are “burned” so you can move. The same system takes away the waste products—

lactic acid and so on—after the “burn,” which is just as important. (The pain when you run out of steam and feel as if you are out of

breath actually comes from the buildup of lactic acid, not muscle pain or lack of air.) And you, our beloved reader, almost certainly

need rebuilding pretty badly, because the likelihood is that you don’t begin to get enough exercise. And in all that idleness, your aerobic base has gone to hell. Do you notice it ? Of course you do. You get out of breath going up one flight of stairs. You shrink from the idea of walking five blocks. You don’t feel like yourself. Stuff like that. It seems minor and temporary but it is not. You know why ? Being able to move is who you are, in nature. In idleness, the little engines, the mitochondria, die off by the million. Your “horsepower” drops sharply. Very sharply. The capillaries that carry food and oxygen to the little engines (and carry away the wastes afterward) dry up and close, and . . . your horsepower drops some more. But here’s the short version: In idleness, the whole system goes to hell, with disastrous consequences. The great news is that aerobic exercise cures rot. Aerobic exercise restores and repairs the aerobic system; it gets you moving again. Pretty darned fast, too. You get millions of new mitochondria, vast new networks of capillaries. In a surprisingly short time, you feel better and are much more able to move freely. - Aerobic exercise reduces disease. Aerobic exercise radically reduces inflammation, which means it eliminates 50 percent of the

worst diseases in our lives forever. By reducing inflammation, serious aerobic exercise eliminates 50 percent of the worst diseases. In the normal course—when you are sitting at your desk or watching TV and your blood is barely trickling around your body—your blood itself is mildly inflammatory. Your own precious blood is making things a little bit worse, with its slow, steady drip of inflammation. But when you do serious aerobic exercise, you change the chemistry of your blood, and it becomes anti-inflammatory. It becomes a powerful, healing balm, coursing through your body, making things radically better. - Aerobic exercise improves your mood and reduces depression. Recent scientific studies support the observed fact that serious aerobic exercise is the single best thing you can do to combat depression and raise mood.

- Aerobic exercise reduces stress.

- Aerobic exercise makes you smarter. Scientific research in the last decade has shown that aerobic exercise grows new brain. You get 10 percent more cognitively efficient.

Any physical activity that increases your heart and breathing rates is considered aerobic activity, including:

- Household chores, such as mowing the lawn, raking leaves, gardening or scrubbing the floor

- Active sports, such as basketball or tennis

- Climbing stairs

- Walking

- Jogging

- Bicycling

- Swimming

- Dancing

Exercise For Overall Cardiovascular Health

The American Heart Association 1 recommends the following amounts of physical activity to maintain cardiovascular health:

- At least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity at least 5 days per week for a total of 150 minutes.

OR

- At least 25 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity at least 3 days per week for a total of 75 minutes; or a combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity.

AND

- Moderate- to high-intensity muscle-strengthening activity at least 2 days per week for additional health benefits.

For Lowering Blood Pressure and Cholesterol

- An average 40 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activity 3 or 4 times per week.

Exercise can lower your blood pressure

Becoming more active can lower your systolic blood pressure — the top number in a blood pressure reading — by an average of 4 to 9 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). That’s as good as some blood pressure medications. For some people, getting some exercise is enough to reduce the need for blood pressure medication.

If your blood pressure is at a desirable level — less than 120/80 mm Hg — exercise can help prevent it from rising as you age. Regular exercise also helps you maintain a healthy weight — another important way to control blood pressure.

But to keep your blood pressure low, you need to keep exercising on a regular basis. It takes about one to three months for regular exercise to have an impact on your blood pressure. The benefits last only as long as you continue to exercise.

Your exercise intensity must generally be at a moderate or vigorous level for maximum benefit. For weight loss, the more intense or longer your activity, the more calories you burn.

Balance is still important. Overdoing it can increase your risk of soreness, injury and burnout. Start at a light intensity if you’re new to exercising. Gradually build up to a moderate or vigorous intensity.

Consider your reasons for exercising. Do you want to improve your fitness, lose weight, train for a competition or do a combination of these ? Your answer will help determine the appropriate level of exercise intensity.

Be realistic and don’t push yourself too hard, too fast. Fitness is a lifetime commitment, not a sprint to a finish line. Talk to your doctor if you have any medical conditions or you’re not sure what your exercise intensity should be.

Activities such as strength training and high-intensity interval training, as well as regularly changing up your exercise routine can help maintain muscle mass, prevent cardiovascular decline and improve balance. All three of these components are essential to living a long, healthy and independent life.

Add these activities to your weekly fitness routine to slow down your body’s clock.

- Endurance exercises. Activities such as running, cycling and swimming are the best ways to improve your cardiovascular function and prevent your metabolism from slowing down. Aim to get at least 30 to 60 minutes of moderate-intensity cardio (aerobic) activity most days, for a total of 150 minutes each week.

- Interval training. Instead of a steady-state bout of running or cycling, with high-intensity interval training, you alternate bursts of intense activity (that makes you breathe heavily) with lighter activity. An example workout would include five intervals at a higher intensity (which may mean increasing speed, incline or resistance) for one to two minutes with a one- to two-minute period in between at a slightly lower intensity. An easy way to determine if you’re working hard enough is whether you can talk (or sing) easily. If you can’t, you’re working hard enough during your intervals. Add interval training to your workout routine one or two days each week.

- Strength training. Maintaining muscle mass is very important as you age, since both men and women lose muscle mass as they age and replace it with fat. Skeletal muscle burns more calories at rest compared to fat tissue. It also protects your joints and can help your bones become stronger and maintain their density, which can prevent fractures. Maintaining and increasing muscle mass can also help improve balance and agility, which is crucial as you get older.

So how can you stop the loss of muscle mass and increase it instead ? It’s simple — lift weights! And no, you don’t need to become a bodybuilder. If your routine doesn’t currently include strength training, start by doing one set of 10 to 15 repetitions of exercises that challenge your major muscle groups, including your chest, back, arms and legs. For example, a chest exercise is a bench press, a back exercise is a row, and a leg exercise is a squat. Do these moves two to three times a week. If you’re already lifting weights, increase the weight regularly. Aim for a modest increase every few weeks — in the range of 2.5 to 10 pounds — and keep track in a diary or journal to make certain you’re increasing regularly. Even if you keep your routine exactly the same, increasing the weight so that your last few repetitions are challenging (but still doable) will help you become stronger, which means more lean muscle tissue — and better calorie-burning potential!

The last way to help slow down age-related changes is to keep adding challenge and variety to your workouts. When you perform an exercise routine over and over, with no change in frequency, intensity, duration or type of exercise, you can plateau. Over time, this lack of challenge may allow age-related changes to creep in before you know it. If you get complacent with your workouts, your body will, too.

Understanding exercise intensity

When you’re doing aerobic activity, such as walking or biking, exercise intensity correlates with how hard the activity feels to you. Exercise intensity is also shown in your breathing and heart rate, whether you’re sweating, and how tired your muscles feel.

There are two basic ways to measure exercise intensity:

- How you feel. Exercise intensity is a subjective measure of how hard physical activity feels to you while you’re doing it — your perceived exertion. Your perceived level of exertion may be different from what someone else feels doing the same exercise. For example, what feels to you like a hard run can feel like an easy workout to someone who’s more fit.

- Your heart rate. Your heart rate offers a more objective look at exercise intensity. In general, the higher your heart rate during physical activity, the higher the exercise intensity.

Studies show that your perceived exertion compares well with your heart rate. So if you think you’re working hard, your heart rate is probably higher than usual.

You can use either way of gauging exercise intensity. If you like technology, a heart rate monitor might be a useful device for you. If you feel you’re in tune with your body and your level of exertion, you likely will do fine without a monitor.

Moderate exercise intensity

Moderate activity feels somewhat hard. Here are clues that your exercise intensity is at a moderate level:

- Your breathing quickens, but you’re not out of breath.

- You develop a light sweat after about 10 minutes of activity.

- You can carry on a conversation, but you can’t sing.

For moderate-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 64% and 76% of your maximum heart rate 2, 3. You can estimate your maximum heart rate based on your age. To estimate your maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220. For example, for a 50-year-old person, the estimated maximum age-related heart rate would be calculated as 220 – 50 years = 170 beats per minute (bpm). The 64% and 76% levels would be:

- 64% level: 170 x 0.64 = 109 bpm, and

- 76% level: 170 x 0.76 = 129 bpm

This shows that moderate-intensity physical activity for a 50-year-old person will require that the heart rate remains between 109 and 129 bpm during physical activity.

Most moderate activities can become vigorous if you increase your effort.

Vigorous exercise intensity

Vigorous activity feels challenging. Here are clues that your exercise intensity is at a vigorous level:

- Your breathing is deep and rapid.

- You develop a sweat after only a few minutes of activity.

- You can’t say more than a few words without pausing for breath.

For vigorous-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 77% and 93% of your maximum heart rate 2, 3. You can estimate your maximum heart rate based on your age. To estimate your maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220. For example, for a 35-year-old person, the estimated maximum age-related heart rate would be calculated as 220 – 35 years = 185 beats per minute (bpm). The 77% and 93% levels would be:

- 77% level: 185 x 0.77 = 142 bpm, and

- 93% level: 185 x 0.93 = 172 bpm

This shows that vigorous-intensity physical activity for a 35-year-old person will require that the heart rate remains between 142 and 172 bpm during physical activity.

In general, 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity can give similar health benefits to 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity.

Gauging intensity using your heart rate

Another way to gauge your exercise intensity is to see how hard your heart is beating during physical activity. To use this method, you first have to figure out your maximum heart rate — the upper limit of what your cardiovascular system can handle during physical activity.

The basic way to calculate your maximum heart rate is to subtract your age from 220. For example, if you’re 45 years old, subtract 45 from 220 to get a maximum heart rate of 175. This is the maximum number of times your heart should beat per minute during exercise.

Maximum Heart Rate = 220 – Age

It’s important to note that maximum heart rate is just a guide. You may have a higher or lower maximum heart rate, sometimes by as much as 15 to 20 beats per minute. If you want a more definitive range, consider discussing your target heart rate zone with an exercise physiologist or a personal trainer.

Once you know your maximum heart rate, you can calculate your desired target heart rate zone — the level at which your heart is being exercised and conditioned but not overworked.

Here’s how heart rate matches up with exercise intensity levels 4:

- Moderate exercise intensity: 64 to 76 percent of your maximum heart rate

- Vigorous exercise intensity: 77 to 93 percent of your maximum heart rate

If you’re not fit or you’re just beginning an exercise program, aim for the lower end of your target zone (50 percent). Then, gradually build up the intensity. If you’re healthy and want a vigorous intensity, opt for the higher end of the zone.

- Taking Your Heart Rate

Generally, to determine whether you are exercising within the heart rate target zone, you must stop exercising briefly to take your pulse. You can take the pulse at the neck, the wrist, or the chest. We recommend the wrist. You can feel the radial pulse on the artery of the wrist in line with the thumb. Place the tips of the index and middle fingers over the artery and press lightly. Do not use the thumb. Take a full 60-second count of the heartbeats, or take for 30 seconds and multiply by 2. Start the count on a beat, which is counted as “zero.” If this number falls between 85 and 119 bpm in the case of the 50-year-old person, he or she is active within the target range for moderate-intensity activity.

How to determine your target heart rate zone?

Use an online calculator to determine your desired target heart rate zone. Or, here’s a simple way to do the math yourself. If you’re aiming for a target heart rate of 70 to 85 percent, which is in the vigorous range, you would calculate it like this:

- Subtract your age from 220 to get your maximum heart rate.

- Calculate your resting heart rate by counting your heart beats per minute when you are at rest, such as first thing in the morning. It’s usually somewhere between 60 and 100 beats per minute for the average adult.

- Calculate your Heart Rate Reserve (HRR) by subtracting your resting heart rate from your maximum heart rate.

- Multiply your HRR by 0.7 (70 percent). Add your resting heart rate to this number.

- Multiply your HRR by 0.85 (85 percent). Add your resting heart rate to this number.

- These two numbers are your training zone heart rate. Your heart rate during exercise should be between these two numbers.

For example, say your age is 30 and you want to figure out your target training heart rate zone. Subtract 30 from 220 to get 190 — this is your maximum heart rate. Next, calculate your HRR by subtracting your resting heart rate of 80 beats per minute from 190. Your Heart Rate Reserve (HRR) is 110. Multiply 110 by O.7 to get 77, then add your resting heart rate of 80 to get 157. Now multiply 110 by O.85 to get 93.5, then add your resting heart rate of 80 to get 173.5. So your target for your training zone heart rate should be between 157 and 173.5 beats per minute.

How to tell if you’re in the target heart rate zone?

So how do you know if you’re in your target heart rate zone? Use these steps to check your heart rate during exercise:

- Stop momentarily.

- Take your pulse for 15 seconds. To check your pulse over your carotid artery, place your index and third fingers on your neck to the side of your windpipe. To check your pulse at your wrist, place two fingers between the bone and the tendon over your radial artery — which is located on the thumb side of your wrist.

- Multiply this number by 4 to calculate your beats per minute.

Here’s an example: You stop exercising and take your pulse for 15 seconds, getting 33 beats. Multiply 33 by 4, to get 132. If you’re 30 years old, this puts you below of your target heart rate zone for vigorous exercise, since that zone is 157 to 173.5 beats per minute. If you’re under or over your target heart rate zone, adjust your exercise intensity.

Also note that several types of medications, including some medications to lower blood pressure, can lower your maximum heart rate and, therefore, lower your target heart rate zone. Ask your doctor if you need to use a lower target heart rate zone because of any medications you take or medical conditions you have.

Interestingly, research shows that high intensity interval training, which includes short bouts (around 15 to 60 seconds) of higher intensity (maximal effort) exercise alternated with longer, less strenuous exercise throughout your workout, is well-tolerated. It’s even safe for those with certain cardiac conditions. This type of training is also very effective at increasing your cardiovascular fitness and promoting weight loss.

You’ll get the most from your workouts if you’re exercising at the proper exercise intensity for your health and fitness goals. If you’re not feeling any exertion or your heart rate is too low, pick up the pace. If you’re worried that you’re pushing yourself too hard or your heart rate is too high, back off a bit.

Stop exercising and seek immediate medical care if you experience any warning signs during exercise, including:

- Chest, neck, jaw or arm pain or tightness

- Dizziness or faintness

- Severe shortness of breath

- An irregular heartbeat

How Much Activity Do People Need to Prevent Weight Gain?

Weight gain during adulthood can increase the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions. Since it’s hard for people to lose weight and keep it off, it’s better to prevent weight gain in the first place. Encouragingly, there’s strong evidence that staying active can help people slow down or stave off “middle-age spread” 5. The more active people are, the more likely they are to keep their weight steady 6; the more sedentary, the more likely they are to gain weight over time 7. But it’s still a matter of debate exactly how much activity people need to avoid gaining weight. The latest evidence suggests that the recommended two and a half hours a week may not be enough.

The Women’s Health Study, for example, followed 34,000 middle-age women for 13 years to see how much physical activity they needed to stay within 5 pounds of their weight at the start of the study. Researchers found that women in the normal weight range at the start needed the equivalent of an hour a day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity to maintain a steady weight 8.

Vigorous activities seem to be more effective for weight control than slow walking 9, 10. The Nurses’ Health Study II 11, for example, followed more than 18,000 women for 16 years to study the relationship between changes in physical activity and weight. Although women gained, on average, about 20 pounds over the course of the study, those who increased their physical activity by 30 minutes per day gained less weight than women whose activity levels stayed steady. And the type of activity made a difference: Bicycling and brisk walking helped women avoid weight gain, but slow walking did not.

How Much Activity Do People Need to Lose Weight?

Exercise can help promote weight loss, but it seems to work best when combined with a lower calorie eating plan 12. If people don’t curb their calories, however, they likely need to exercise for long periods of time-or at a high intensity-to lose weight 13, 14.

In one study 13, for example, researchers randomly assigned 175 overweight, inactive adults to either a control group that did not receive any exercise instruction or to one of three exercise regimens-low intensity (equivalent to walking 12 miles/week), medium intensity (equivalent to jogging 12 miles/week), or high intensity (equivalent to jogging 20 miles per week). All study volunteers were asked to stick to their usual diets. After six months, those assigned to the high-intensity regimen lost abdominal fat, whereas those assigned to the low- and medium-intensity exercise regimens had no change in abdominal fat 13.

More recently, researchers conducted a similar trial with 320 post-menopausal women 15, randomly assigning them to either 45 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity, five days a week, or to a control group. Most of the women were overweight or obese at the start of the study. After one year, the exercisers had significant decreases in body weight, body fat, and abdominal fat, compared to the non-exercisers 15.

The Bottom Line

- For Weight Control, Aim for an Hour of Activity a Day

Being moderately active for at least 30 minutes a day on most days of the week can help lower the risk of chronic disease. But to stay at a healthy weight, or to lose weight, most people will need more physical activity-at least an hour a day-to counteract the effects of increasingly sedentary lifestyles, as well as the strong societal influences that encourage overeating.

Keep in mind that staying active is not purely an individual choice: The so-called “built environment”-buildings, neighborhoods, transportation systems, and other human-made elements of the landscape-influences how active people are 16. People are more prone to be active, for example, if they live near parks or playgrounds, in neighborhoods with sidewalks or bike paths, or close enough to work, school, or shopping to safely travel by bike or on foot. People are less likely to be active if they live in sprawling suburbs designed for driving or in neighborhoods without recreation opportunities.

Local and state governments wield several policy tools for shaping people’s physical surroundings, such as planning, zoning, and other regulations, as well as setting budget priorities for transportation and infrastructure. Strategies to create safe, active environments include curbing traffic to make walking and cycling safer, building schools and shops within walking distance of neighborhoods, and improving public transportation, to name a few. Such changes are essential to make physical activity an integral and natural part of people’s everyday lives-and ultimately, to turn around the obesity epidemic.

How much exercise do you need for general good health?

For general good health, the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 17 recommends that adults get a minimum of 2-1/2 hours per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity. Yet many people may need more than 2-1/2 hours of moderate intensity activity a week to stay at a stable weight 17.

The Women’s Health Study 18, for example, followed 34,000 middle-aged women for 13 years to see just how much physical activity they needed to stay within 5 pounds of their weight at the start of the study. Researchers found that women who were in the normal weight range at the start of the study needed the equivalent of an hour a day of physical activity to stay at a steady weight 18.

If you are exercising mainly to lose weight, 60 minutes or so a day may be effective in conjunction with a healthy diet 19.

If you currently don’t exercise and aren’t very active during the day, any increase in exercise or physical activity is good for you.

Aerobic physical activity—any activity that causes a noticeable increase in your heart rate—is especially beneficial for disease prevention.

Some studies show that walking briskly for even one to two hours a week (15 to 20 minutes a day) starts to decrease the chances of having a heart attack or stroke, developing diabetes, or dying prematurely.

You can combine moderate and vigorous exercise over the course of the week, and it’s fine to break up your activity into smaller bursts as long as you sustain the activity for at least 10 minutes.

Exercise Intensity:

Moderate-intensity aerobic activity is any activity that causes a slight but noticeable increase in breathing and heart rate. One way to gauge moderate activity is with the “talk test”—exercising hard enough to break a sweat but not so hard you can’t comfortably carry on a conversation.

Vigorous-intensity aerobic activity causes more rapid breathing and a greater increase in heart rate, but you should still be able to carry on a conversation—with shorter sentences.

Here is a summary of the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 17

Children and adolescents should get at least 1 hour or more a day of physical activity in age-appropriate activities, spending most of that engaged in moderate- or vigorous–intensity aerobic activities. They should partake in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity on at least three days of the week, and include muscle-strengthening and bone strengthening activities on at least three days of the week.

Healthy adults should get a minimum of 2-1/2 hours per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, or a minimum of 1-1/4 hours per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, or a combination of the two. That could mean a brisk walk for 30 minutes a day, five days a week; a high-intensity spinning class one day for 45 minutes, plus a half hour jog another day; or some other combination of moderate and vigorous activity. Doubling the amount of activity (5 hours moderate- or 2-1/2 hours vigorous-intensity aerobic activity) provides even more health benefits. Adults should also aim to do muscle-strengthening activities at least two days a week.

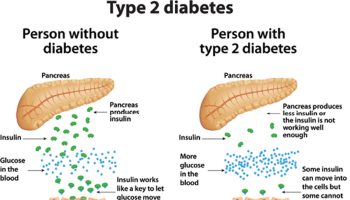

Healthy older Adults should follow the guidelines for healthy adults. Older adults who cannot meet the guidelines for healthy adults because of chronic conditions should be as physically active as their abilities and conditions allow. People who have chronic conditions such as arthritis and type 2 diabetes should talk to a healthcare provider about the amount and type of activity that is best. Physical activity can help people manage chronic conditions, as long as the activities that individuals choose match their fitness level and abilities. Even just an hour a week of activity has health benefits. Older adults who are at risk of falling should include activities that promote balance.

Strength training for all ages

Studies have shown strength training to increase lean body mass, decrease fat mass, and increase resting metabolic rate (a measurement of the amount of calories burned per day) in adults 20. While strength training on its own typically does not lead to weight loss 17, its beneficial effects on body composition may make it easier to manage one’s weight and ultimately reduce the risk of disease, by slowing the gain of fat—especially abdominal fat 21.

- Muscle is metabolically active tissue; it utilizes calories to work, repair, and refuel itself. Fat, on the other hand, doesn’t use as much energy. We slowly lose muscle as part of the natural aging process, which means that the amount of calories we need each day starts to decrease, and it becomes easier to gain weight.

- Strength training regularly helps preserve lean muscle tissue and can even rebuild some that has been lost already.

- Weight training has also been shown to help fight osteoporosis. For example, a study in postmenopausal women examined whether regular strength training and high-impact aerobics sessions would help prevent osteoporosis. Researchers found that the women who participated in at least two sessions a week for three years were able to preserve bone mineral density at the spine and hip; over the same time period, a sedentary control group showed bone mineral density losses of 2 to 8 percent 22.

- In older populations, resistance training can help maintain the ability to perform functional tasks such as walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and even carrying one’s own groceries. An emerging area of research suggests that muscular strength and fitness may also be important to reducing the risk of chronic disease and mortality, but more research is needed 23, 24.

- A systematic review of 8 studies 25 examining the effects of weight-bearing and resistance-based exercises on the bone mineral density in older men found resistance training to be an effective strategy for preventing osteoporosis in this population. Resistance training was found to have more positive effects on bone mineral density than walking, which has a lower impact 25.

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommends that muscle strengthening activities be done at least two days a week 17. Different types of strength training activities are best for different age groups.

- When talking about the benefits of exercise, keeping the heart and blood vessels healthy usually gets most of the attention. For many individuals, though, stretching and strength training exercises may be just as important.

- Strength training, also known as resistance training, weight training, or muscle-strengthening activity, is one of the most beneficial components of a fitness program.

Children and Adolescents: Choose unstructured activities rather than weight lifting exercises 17.

Examples:

- Playing on playground equipment

- Climbing trees

- Playing tug-of-war

Active Adults: Weight training is a familiar example, but there are other options 17:

- Calisthenics that use body weight for resistance (such as push-ups, pull-ups, and sit-ups)

- Carrying heavy loads

- Heavy gardening (such as digging or hoeing)

Older Adults: The guidelines for older adults are similar to those for adults; older adults who have chronic conditions should consult with a health care provider to set their activity goals. Muscle strengthening activities in this age group include the following 17:

- Digging, lifting, and carrying as part of gardening

- Carrying groceries

- Some yoga and tai chi exercises

- Strength exercises done as part of a rehab program or physical therapy

Flexibility training

Flexibility training or stretching exercise is another important part of overall fitness. It may help older adults preserve the range of motion they need to perform daily tasks and other physical activities 26.

- The American Heart Association 20 recommends that healthy adults engage in flexibility training two to three days per week, stretching major muscle and tendon groups.

- For older adults, the American Heart Association and American College of Sports Medicine recommend two days a week of flexibility training, in sessions at least 10 minutes long 26. Older adults who are at risk of falling should also do exercises to improve their balance.

- American Heart Association, Go Red for Womens : What Exercise is Right for Me ? – https://www.goredforwomen.org/live-healthy/heart-healthy-exercises/what-exercise-is-right-for-me/

- Jensen MT, Suadicani P, Hein HO, et al. Elevated resting heart rate, physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a 16-year follow-up in the Copenhagen Male Study. Heart 2013;99:882-887. https://heart.bmj.com/content/heartjnl/99/12/882.full.pdf

- All About Heart Rate (Pulse). https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/the-facts-about-high-blood-pressure/all-about-heart-rate-pulse

- Target Heart Rate and Estimated Maximum Heart Rate. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/heartrate.htm

- Wareham NJ, van Sluijs EM, Ekelund U. Physical activity and obesity prevention: a review of the current evidence. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005; 64:229-47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15960868

- Seo DC, Li K. Leisure-time physical activity dose-response effects on obesity among US adults: results from the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010; 64:426-31. http://jech.bmj.com/content/64/5/426.long

- Lewis CE, Smith DE, Wallace DD, Williams OD, Bild DE, Jacobs DR, Jr. Seven-year trends in body weight and associations with lifestyle and behavioral characteristics in black and white young adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 1997; 87:635-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1380845/pdf/amjph00503-0109.pdf

- Lee IM, Djousse L, Sesso HD, Wang L, Buring JE. Physical activity and weight gain prevention. JAMA. 2010; 303:1173-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2846540/

- Lusk AC, Mekary RA, Feskanich D, Willett WC. Bicycle riding, walking, and weight gain in premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170:1050-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3119355/

- Mekary RA, Feskanich D, Malspeis S, Hu FB, Willett WC, Field AE. Physical activity patterns and prevention of weight gain in premenopausal women. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009; 33:1039-47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2746452/

- Mekary RA, Feskanich D, Hu FB, Willett WC, Field AE. Physical activity in relation to long-term maintenance after intentional weight loss in premenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2010;18(1):167-174. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.170. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2798010/

- U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans; 2008. https://health.gov/paguidelines/

- Slentz CA, Aiken LB, Houmard JA, et al. Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. J Appl Physiol. 2005; 99:1613-8. https://www.physiology.org/doi/pdf/10.1152/japplphysiol.00124.2005

- McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Irwin ML, et al. Exercise effect on weight and body fat in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007; 15:1496-512. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1038/oby.2007.178

- Friedenreich CM, Woolcott CG, McTiernan A, et al. Adiposity changes after a 1-year aerobic exercise intervention among postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3061001/

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009; 87:123-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2879180/

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. https://health.gov/paguidelines/

- Lee, I.M., et al., Physical activity and weight gain prevention. JAMA, 2010. 303(12): p. 1173-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2846540/

- Jakicic, J.M., et al., Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women: a randomized trial. JAMA, 2003. 290(10): p. 1323-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12966123

- Williams, M.A., et al., Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation, 2007. 116(5): p. 572-84. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/116/5/572.long

- Schmitz, K.H., et al., Strength training and adiposity in premenopausal women: strong, healthy, and empowered study. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007. 86(3): p. 566-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17823418

- Engelke, K., et al., Exercise maintains bone density at spine and hip EFOPS: a 3-year longitudinal study in early postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int, 2006. 17(1): p. 133-42.

- Ling, C.H., et al., Handgrip strength and mortality in the oldest old population: the Leiden 85-plus study. CMAJ, 2010. 182(5): p. 429-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842834

- Ruiz, J.R., et al., Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ, 2008. 337: p. a439. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2453303/

- Bolam, K.A., J.G. van Uffelen, and D.R. Taaffe, The effect of physical exercise on bone density in middle-aged and older men: A systematic review. Osteoporos Int, 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0055053/

- Nelson, M.E., et al., Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2007. 116(9): p. 1094-105. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/116/9/1094.long