What is hemangioblastoma

Hemangioblastoma is a benign, highly vascular tumor that can occur in the brain, spinal cord, and retina (the light-sensitive tissue that lines the back of the eye). A hemangioblastoma tumor accounts for about 2% of brain tumors. According to the World Health Organization classification of tumors of the nervous system, hemangioblastomas are classified as meningeal tumors of uncertain origin 1. As hemangioblastoma enlarges, it presses on the brain and can cause neurological symptoms, such as headaches, weakness, sensory loss, balance and coordination problems and/or hydrocephalus (a buildup of spinal fluid in the brain). Most hemangioblastomas occur sporadically. However, some people develop hemangioblastomas as part of a genetic syndrome called von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. These people usually develop multiple tumors within the brain and spinal cord over their lifetime 2.

Hemangioblastomas are rare, and according to various series, they account for 1-2.5% of all intracranial neoplasms 3. Most hemangioblastomas are located in the posterior cranial fossa; in that region, hemangioblastomas comprise 8-12% of neoplasms. Hemangioblastoma is the most common primary adult intra-axial posterior fossa tumor 4. Cerebellar hemangioblastomas are frequently referred to as Lindau tumors because Swedish pathologist Arvid Vilhelm Lindau first described them in 1926 5.

The second most common location of hemangioblastomas is the spinal cord 6, where the frequency ranges from 2-3% of primary spinal cord neoplasms to 7-11% of spinal cord tumors. This tumor’s occurrence in other locations, such as the supratentorial compartment 7, the optic nerve 8, the peripheral nerves 9 or the soft tissues of extremities 10 is extremely rare.

Hemangioblastomas are more common in men than in women. In most clinical series, the male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1. Although hemangioblastomas may develop at any age, they rarely affect children; the usual age at diagnosis is between the third and fifth decades.

The peak age of incidence has been noted to be between 20 and 50 years. Hemangioblastomas are uncommon but not rare in patients older than 65 years. In a study at one institution, all patients (N = 77) were older than 18 years, and 6 of those were older than 65 years 11.

Because hemangioblastomas are benign tumors and generally are not invasive in nature they may be cured by surgical excision. Therefore, surgical resection is considered a standard of treatment and should be offered to the patient unless the risk of operation outweighs its potential benefits 12.

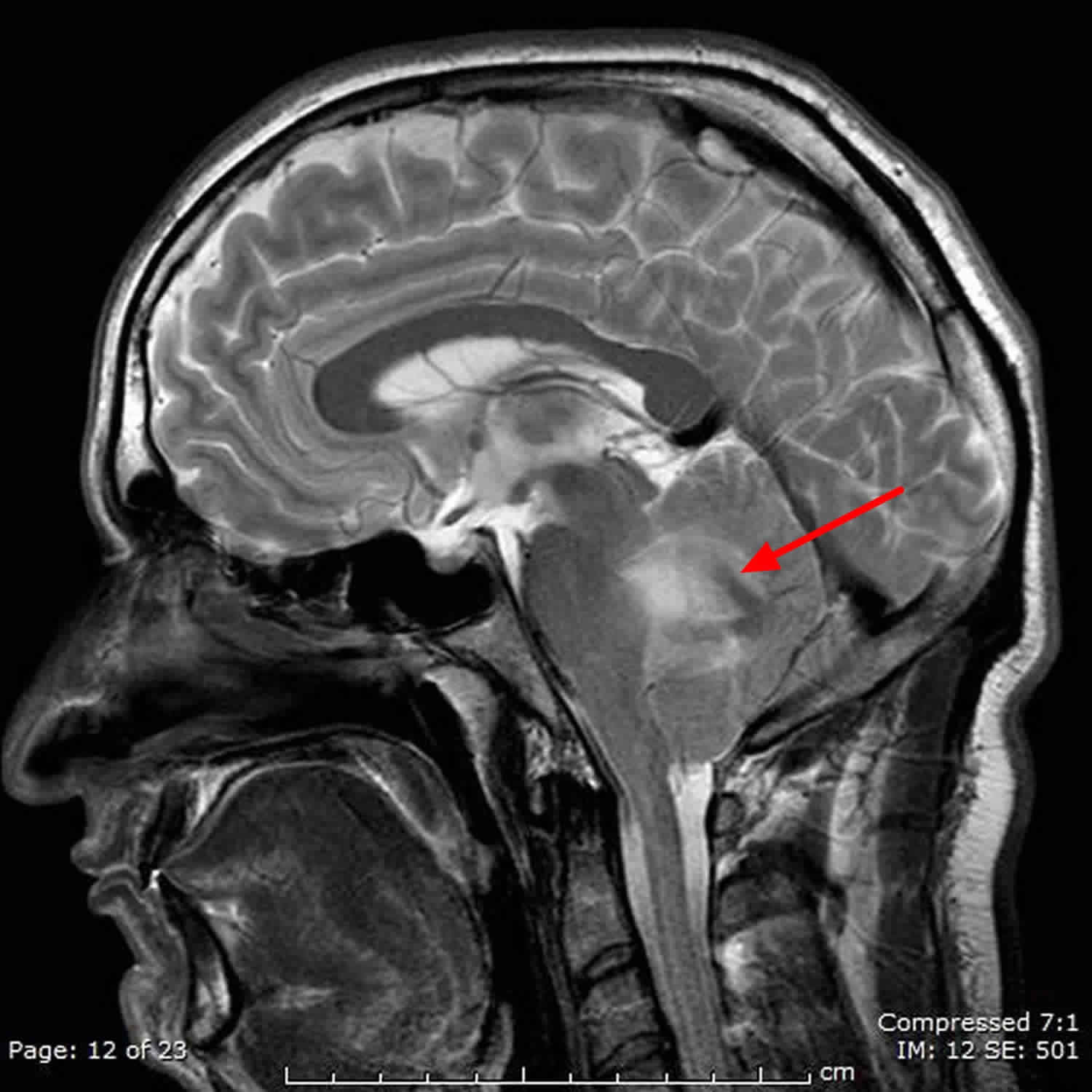

Figure 1. Hemangioblastoma of the retina

Footnote: Fundoscopic photograph illustrating a retinal hemangioblastoma (arrows)

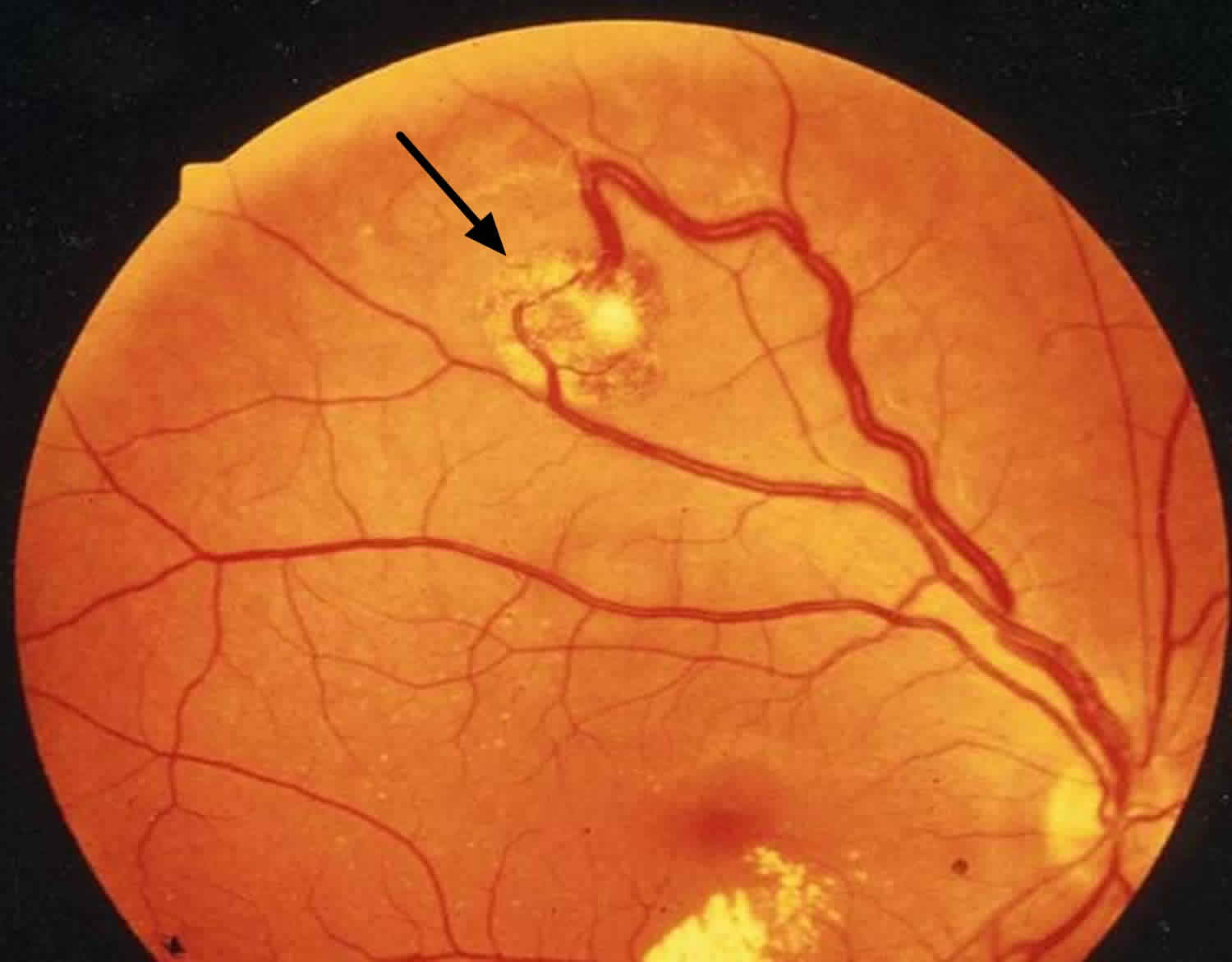

Figure 2. Hemangioblastoma spine

Footnote: A central vividly enhancing mass (green arrows) is surrounded by cystic elements and has a prominent serpiginous flow void posteriorly (red arrow). The entire cord is edematous, and the peritumoural cists are lined by hemosiderin (blue arrow).

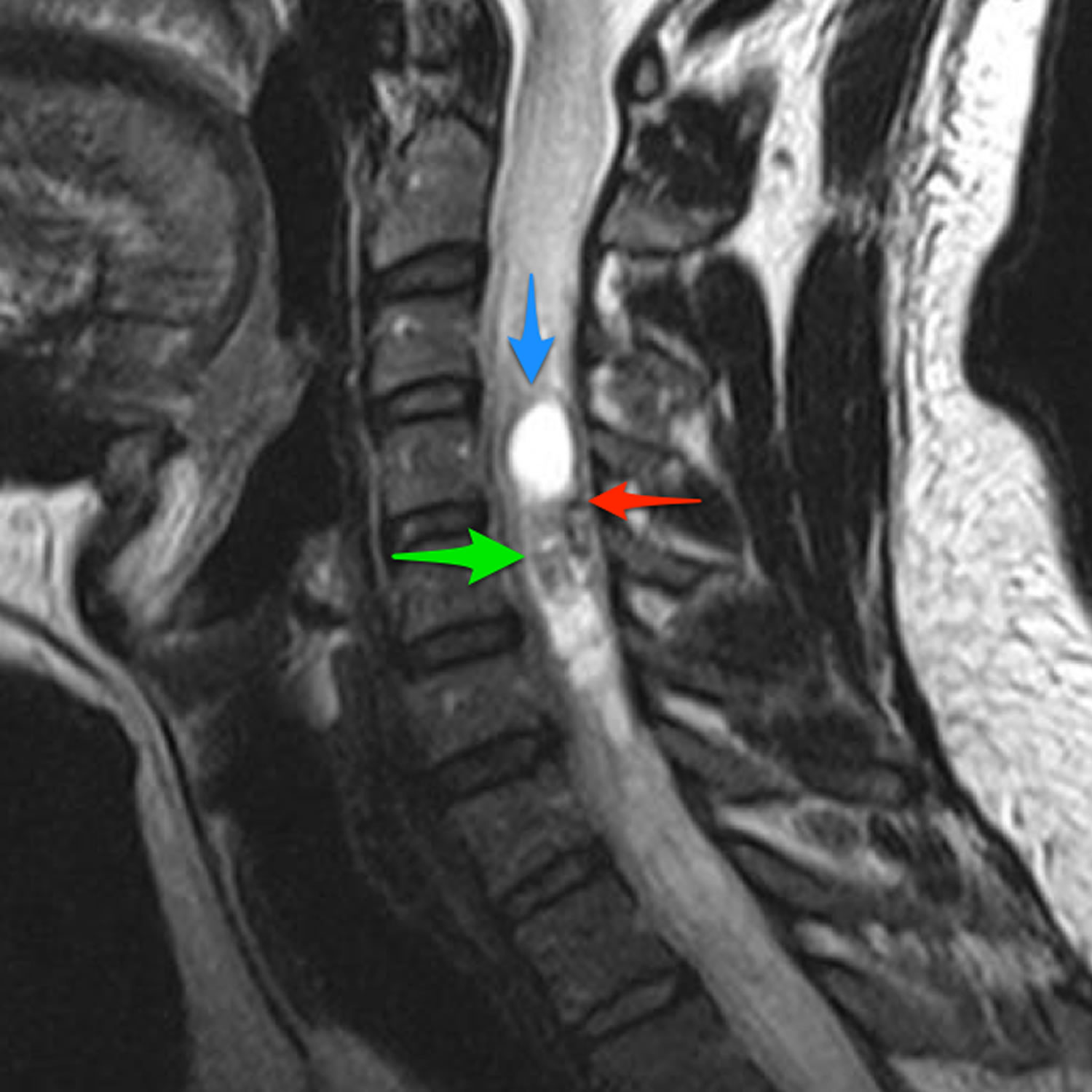

Figure 3. Hemangioblastoma brain

Footnote: Cystic lesion with non enhancing walls and vividly enhancing mural nodule in cerebellum = cerebellar hemangioblastoma

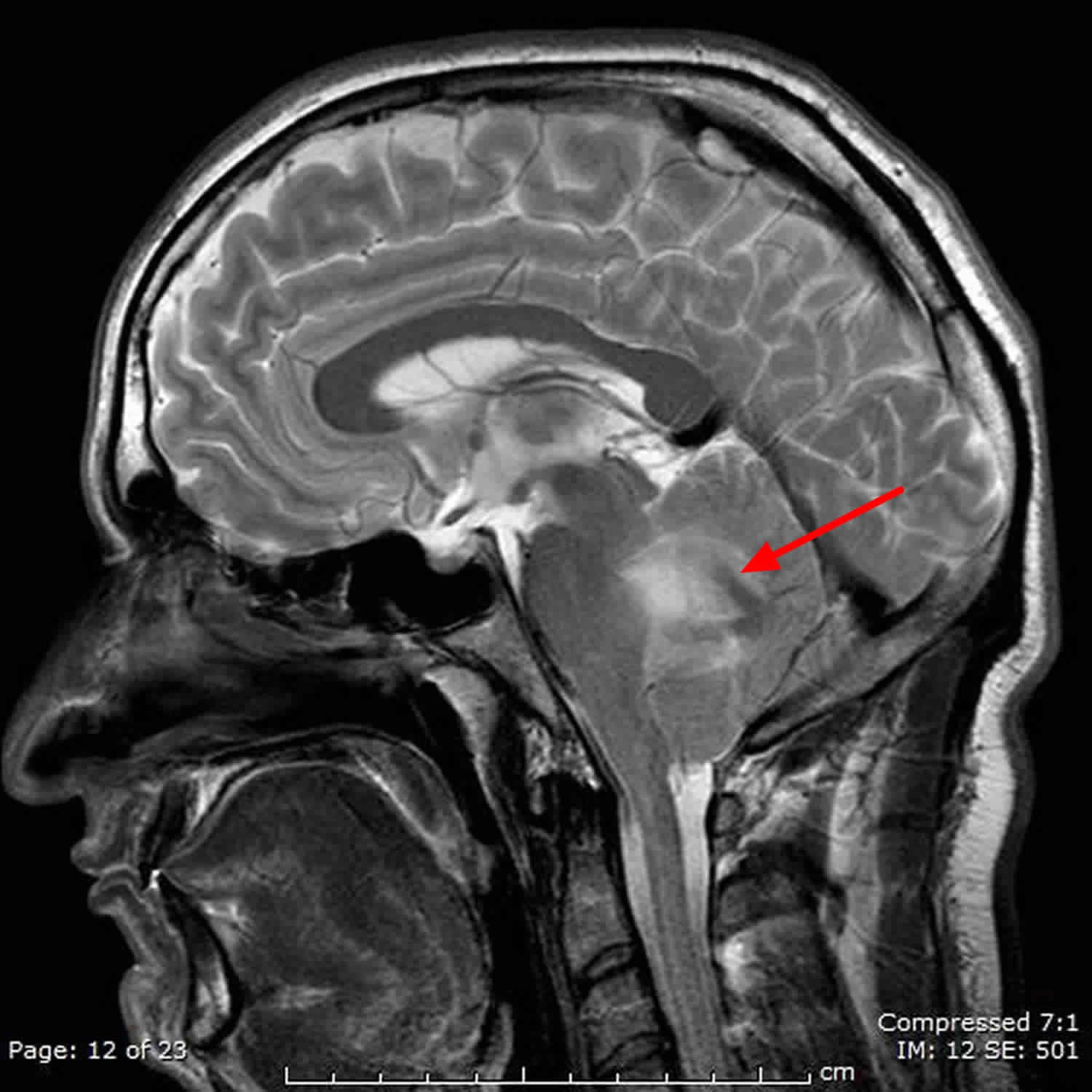

Figure 4. Cerebellar hemangioblastoma

Footnote: Intra-axial cystic right cerebellar hemispheric mass lesion containing intensely enhancing peripheral mural nodule. The cystic part is isointense T1, hyperintense T2/FLAIR and the soft tissue nodule is isointense on T1 and T2. The mass effect is better appreciated by MRI; compression effect on the brainstem and the fourth ventricle, crowded foramen magnum.

Hemangioblastoma vs Hemangioma

Hemangioma is an abnormal buildup of blood vessels in the skin or internal organs. Most hemangiomas are on the face and neck. About one third of hemangiomas are present at birth. The rest appear in the first several months of life.

The hemangioma may be:

- In the top skin layers (capillary hemangioma)

- Deeper in the skin (cavernous hemangioma)

- A mixture of both

Symptoms of a hemangioma are:

- A red to reddish-purple, raised sore (lesion) on the skin

- A massive, raised, tumor with blood vessels

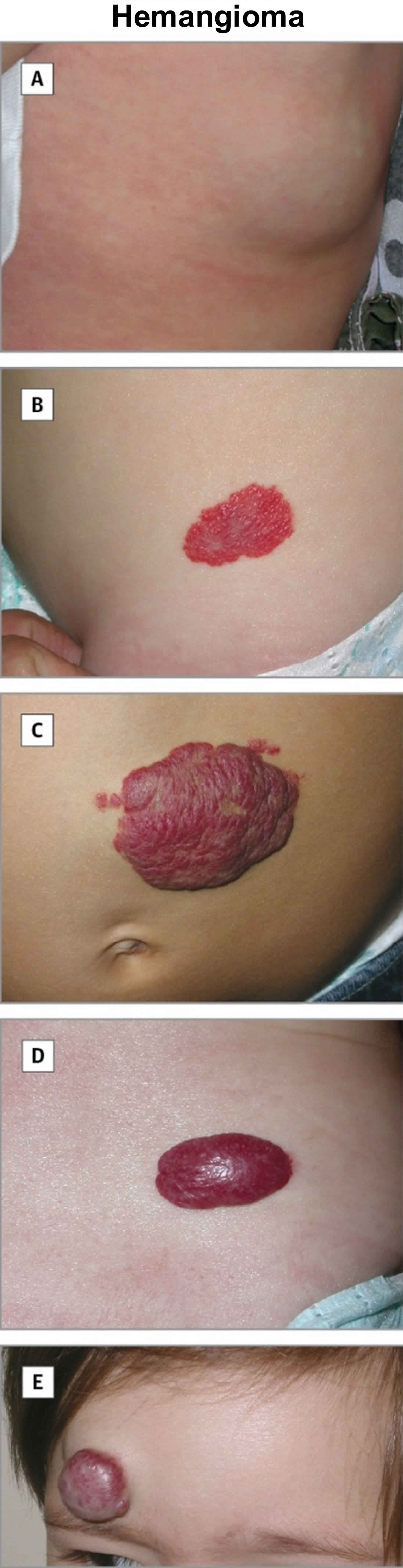

Figure 5. Hemangioma

Footnote: A, deep hemangioma; B, superficial hemangioma; C, mixed hemangioma; D, mixed hemangioma; and E, mixed hemangioma.

These complications can occur from a hemangioma:

- Bleeding (especially if the hemangioma is injured)

- Problems with breathing and eating

- Psychological problems, from skin appearance

- Secondary infections and sores

- Visible changes in the skin

- Vision problems

The majority of small or uncomplicated hemangiomas may not need treatment. They often go away on their own and the appearance of the skin returns to normal. Small superficial hemangiomas will often disappear on their own. About one half go away by age 5, and almost all disappear by age 7. Sometimes, a laser may be used to remove the small blood vessels.

Cavernous hemangiomas that involve the eyelid and block vision can be treated with lasers or steroid injections to shrink them. This allows vision to develop normally. Large cavernous hemangiomas or mixed hemangiomas may be treated with steroids, taken by mouth or injected into the hemangioma.

Taking beta-blocker medicines may also help reduce the size of a hemangioma.

What causes hemangioblastoma?

Most hemangioblastomas rise sporadically, without a known cause. However, in about one quarter of all cases, they are associated with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome 2. von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is an inherited condition characterized by the abnormal growth of tumors in certain parts of the body. The specific tumors that are associated with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome include hemangioblastomas of the brain, spinal cord, and retina; kidney cysts and clear cell kidney cell carcinoma; pheochromocytomas; and endolymphatic sac tumors. Mutations in the VHL gene cause von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. These mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern 13.

The genetic hallmark of hemangioblastomas is the loss of function of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein 14. Upon gross examination, hemangioblastomas are usually cherry red in color. They may include a cyst that contains a clear fluid, but solid tumors are as common as cystic ones. The tumor usually grows inside the parenchyma of the cerebellum, brain stem, or spinal cord; it is attached to the pia mater and gets its rich vascular supply from the pial vessels. However, extramedullary and extradural hemangioblastomas have also been described 15.

Hemangioblastoma symptoms

The clinical presentation of hemangioblastomas usually depends on the anatomic location and growth patterns. Cerebellar lesions may present with signs of cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia and discoordination, or with symptoms of increased intracranial pressure due to associated hydrocephalus 16. In general, intracranial hemangioblastomas present with a long history of minor neurologic symptoms that, in most cases, are followed by a sudden exacerbation, which may necessitate immediate neurosurgical intervention.

Patients with spinal cord lesions most frequently present with pain, followed by signs of segmental and long-track dysfunction due to progressive compression of the spinal cord. Patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease may present with ocular or systemic symptoms due to involvement of other organs and systems.

The polycythemia that may develop in some patients with hemangioblastomas usually is clinically asymptomatic.

Spontaneous hemorrhage is possible in both intraspinal and intracranial hemangioblastomas 17, but this risk is low, and tumors smaller than 1.5 cm carry virtually no risk of spontaneous hemorrhage.

Doyle and Fletcher described 22 cases of hemangioblastoma arising at peripheral sites. All the tumors were solitary, except 1, and arose in the spinal nerve roots (12), kidney (3), intestine (2), orbit (1), forearm (1), peritoneum (1), periadrenal soft tissue (1), and flank (1). Five patients had von Hippel-Lindau disease, and another 5 had lesions suggestive of von Hippel-Lindau disease 18.

Hemangioblastoma diagnosis

Your doctor will perform blood tests to help reveal associated lesions that may be a part of the von Hippel-Lindau disease complex. Unfortunately, finding polycythemia does not help in diagnosing the tumor.

The diagnostic workup of suspected hemangioblastomas must include, in addition to history, physical, and thorough neurologic examination, complete neural axis imaging and abdominal CT scan or ultrasound. The goal of these additional tests is to reveal associated lesions that may be a part of von Hippel-Lindau disease complex.

Your doctor will perform a detailed ophthalmologic evaluation to help reveal associated lesions that may be a part of the von Hippel-Lindau disease complex.

Imaging Studies

Radiographically, hemangioblastomas are best diagnosed with MRI 19. MRI of hemangioblastomas usually shows an enhancing mass clearly delineated from the surrounding brain or spinal cord tissue. The tumor tissue may be hypointense or isointense on precontrast T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images 20.

Plain radiographs usually do not aid in diagnosis. Myelography and cisternography, which were considered the tests of choice in the past, now are almost never used in the diagnostic workup of hemangioblastomas.

Plain computed tomography (CT) scan may reveal hypodensity of the tumoral cyst and associated hydrocephalus. CT scans with intravenous contrast show uniform enhancement of the tumor nodule that, in association with the adjacent cyst, may be extremely characteristic of posterior fossa hemangioblastomas.

Cerebral and spinal angiography reveals a highly vascular tumor blush, and this diagnostic modality may be extremely useful for assessing the vascular supply to the tumor. This information may help the surgeon during tumor resection.

In patients with hemangioblastomas, complete neural axis imaging usually is recommended to rule out multiple lesions, especially in those cases in which VHL syndrome is either diagnosed or clinically suspected.

Hemangioblastoma treatment

Surgery is considered the standard treatment for hemangioblastoma and usually cures this condition. Following surgery, individuals who have had a hemangioblastoma should continue to visit their physician regularly for physical examinations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. These suggested guidelines for follow-up after hemangioblastoma do not state how frequently physician visits or MRIs should be.

The tumors usually are well demarcated from the surrounding brain or spinal cord, but this border of separation does not contain any particular membrane or capsule. The surgical approach must be wide enough to avoid compression of the healthy tissues during retraction. Thorough evaluation of preoperative imaging studies is the key to the safest possible exposure of the tumor. In addition to MRI and CT scans, review the angiography findings to identify the principal blood supply to the tumor mass.

Other therapeutic modalities include endovascular embolization of the solid component of the tumor 21, which may decrease the vascularity of the tumor and lower blood loss during its resection, and stereotactic radiosurgery of the tumor using either a linear accelerator 22 or a gamma knife 23. After studying 186 patients from 6 centers in the North American Gamma Knife Consortium, Kano et al concluded that stereotactic radiosurgery provided control of growing tumors seen on serial imaging studies in 79-92% of cases 24. Antiangiogenic treatment of hemangioblastoma has also been described 25.

Regarding general surgical management, having blood products available for transfusion is very important because the vascular character of hemangioblastomas may result in serious intraoperative blood loss. Additionally, anesthesia for patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease may be quite challenging because of associated renal and endocrine dysfunction.

The tumor is usually easy to visualize because of its reddish-colored solid component and the yellow fluid inside the cyst.

If the cyst is present, it may be emptied by cutting the covering pial membrane or by aspirating the cystic contents using a syringe with a short small-caliber needle. Decompression of the cyst allows for improved delineation of the interface between the tumor and the brain or spinal cord.

The surface of the tumor may be coagulated with wide bipolar forceps; however, avoid penetration of the tumor itself because of its extreme vascularity and difficulties with hemostasis. Try to dissect the tumor circumferentially by careful coagulation and cutting the small feeding vessels and adhesions between the tumor and the surrounding brain or spinal cord and by putting cottonoid strips into the developing plane to avoid direct pressure on the brain or spinal cord tissue.

Once the feeding vessels are identified, they are coagulated and cut. Try to coagulate the arterial feeders prior to the draining veins, but this is not as crucial as it is in arteriovenous malformations.

After the tumor is totally removed, the raw surface of the brain or spinal cord remains relatively bloodless, and the oozing blood stops after a few minutes of gently packing the resection cavity with wet cotton balls, avoiding the need for additional coagulation.

If an associated hydrocephalus exists, it must be addressed separately, usually by means of external ventricular drainage prior to tumor resection. After the tumor is removed, the need for permanent shunt placement may be determined by the patient’s response to external ventricular drainage clamping. In most cases, an intramedullary syrinx does not require a separate drainage procedure because it usually resolves after tumor removal.

With an adequate preoperative workup, most complications of surgery for hemangioblastoma may be avoided. Meticulous maintenance of hemostasis, attention to minor details, and great respect for neural and vascular elements may significantly decrease the risk of postoperative complications. The main emphasis, as usual, should be placed on preventing complications rather than on treatment.

Follow-up care for patients with hemangioblastomas should include regular neurologic and imaging checks to confirm the absence of tumor recurrence and/or development of distant lesions.

Hemangioblastoma survival rate

Long-term results of hemangioblastoma management are generally favorable. Advancement of neuroimaging methods, improvements in microsurgical technique, and the addition of preoperative embolization have significantly lowered morbidity and mortality associated with hemangioblastoma surgery.

Subarachnoid dissemination of hemangioblastomas is extremely rare 26 and local recurrences after complete tumor resection seem to be more frequent in patients with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, in patients diagnosed at a young age, and in patients with multiple hemangioblastomas. The results of one study found that resection of brainstem hemangioblastomas is generally a safe and effective treatment for patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. However, due to von Hippel-Lindau disease–associated progression, long-term decline in functional status may occur 27. The recurrence rates vary in different surgical series but generally remain less than 25%. Histologic subtype has been found to correlate with a probability of hemangioblastoma recurrence, with a 25% recurrence rate in cellular subtype and an 8% recurrence rate in reticular subtype 28.

At final follow-up examination of patients who underwent resection of sporadic hemangioblastoma in the cerebellum, patients with solid tumors more frequently showed poor outcomes than patients with cystic tumors. According to the study authors, the solid configuration observed on preoperative images of sporadic cerebellar hemangioblastomas is one of the most important clinical factors related to both immediate and long-term outcomes after surgery 29.

References- Gonzales MF. Classification and pathogenesis of brain tumors. Kaye AH, Laws ER, eds. Brain Tumors. 1st ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. 31-45.

- Hemangioblastoma. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/250670-overview

- Neumann HP, Eggert HR, Weigel K, Friedburg H, Wiestler OD, Schollmeyer P. Hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. A 10-year study with special reference to von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1989 Jan. 70(1):24-30.

- Constans JP, Meder F, Maiuri F, Donzelli R, Spaziante R, de Divitiis E. Posterior fossa hemangioblastomas. Surg Neurol. 1986 Mar. 25(3):269-75.

- Lindau A. Studien uber Kleinhirncysten. Bau, Pathogenese und Beizeihunger zur Angiomatosis Retinae. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1926. 1(Suppl):3-120.

- Roonprapunt C, Silvera VM, Setton A, Freed D, Epstein FJ, Jallo GI. Surgical management of isolated hemangioblastomas of the spinal cord. Neurosurgery. 2001 Aug. 49(2):321-7; discussion 327-8.

- Peker S, Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Sun I, Sav A, Pamir MN. Suprasellar haemangioblastoma. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2005 Jan. 12(1):85-9.

- Kerr DJ, Scheithauer BW, Miller GM, Ebersold MJ, McPhee TJ. Hemangioblastoma of the optic nerve: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995 Mar. 36(3):573-80; discussion 580-1.

- Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Hellbusch LC, et al. Peripheral nerve hemangioblastoma. Mod Pathol. 1998 Oct. 11(10):999-1004.

- Patton KT, Satcher RL Jr, Laskin WB. Capillary hemangioblastoma of soft tissue: report of a case and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2005 Oct. 36(10):1135-9.

- Yoon JY, Gao A, Das S, Munoz DG. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of hemangioblastomas in the elderly: An update. J Clin Neurosci. 2017 Sep. 43:264-266.

- Imagama S, Ito Z, Ando K, Kobayashi K, Hida T, Ito K, et al. Rapid Worsening of Symptoms and High Cell Proliferative Activity in Intra- and Extramedullary Spinal Hemangioblastoma: A Need for Earlier Surgery. Global Spine J. 2017 Feb. 7 (1):6-13.

- Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/von-hippel-lindau-syndrome

- Zagzag D, Krishnamachary B, Yee H, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005 Jul 15. 65(14):6178-88.

- Agostinelli C, Roncaroli F, Galassi E, Bernardi B, Acciarri N, Tani G. Leptomeningeal hemangioblastoma. Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2004 Aug. 101(1 Suppl):122.

- Morais BA, Cardeal DD, Ribeiro E Ribeiro R, Frassetto FP, Andrade FG, Matushita H, et al. Hydrocephalus: a rare initial manifestation of sporadic intramedullary hemangioblastoma : Intramedullary hemangioblastoma presenting as hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017 Aug. 33 (8):1399-1403.

- Gläsker S, Van Velthoven V. Risk of hemorrhage in hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. Neurosurgery. 2005 Jul. 57(1):71-6; discussion 71-6.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. Peripheral hemangioblastoma: clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014 Jan. 38 (1):119-27.

- Lee SR, Sanches J, Mark AS, Dillon WP, Norman D, Newton TH. Posterior fossa hemangioblastomas: MR imaging. Radiology. 1989 May. 171(2):463-8.

- Arima H, Hasegawa T, Togawa D, Yamato Y, Kobayashi S, Yasuda T, et al. Feasibility of a novel diagnostic chart of intramedullary spinal cord tumors in magnetic resonance imaging. Spinal Cord. 2014 Oct. 52 (10):769-73.

- Takeuchi S, Tanaka R, Fujii Y, Abe H, Ito Y. Surgical treatment of hemangioblastomas with presurgical endovascular embolization. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2001 May. 41(5):246-51; discussion 251-2.

- Chang SD, Meisel JA, Hancock SL, Martin DP, McManus M, Adler JR Jr. Treatment of hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease with linear accelerator-based radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 1998 Jul. 43(1):28-34; discussion 34-5.

- Pan L, Wang EM, Wang BJ, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for hemangioblastomas. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1998 Oct. 70 Suppl 1:179-86.

- Kano H, Shuto T, Iwai Y, Sheehan J, Yamamoto M, McBride HL, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial hemangioblastomas: a retrospective international outcome study. J Neurosurg. 2015 Jun. 122 (6):1469-78.

- Schuch G, de Wit M, Holtje J, et al. Case 2. Hemangioblastomas: diagnosis of von Hippel-Lindau disease and antiangiogenic treatment with SU5416. J Clin Oncol. 2005 May 20. 23(15):3624-6.

- Hande AM, Nagpal RD. Cerebellar haemangioblastoma with extensive dissemination. Br J Neurosurg. 1996 Oct. 10(5):507-11.

- Wind JJ, Bakhtian KD, Sweet JA, Mehta GU, Thawani JP, Asthagiri AR, et al. Long-term outcome after resection of brainstem hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2011 May. 114(5):1312-8.

- Hasselblatt M, Jeibmann A, Gerss J, et al. Cellular and reticular variants of haemangioblastoma revisited: a clinicopathologic study of 88 cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005 Dec. 31(6):618-22.

- Fukuda M, Takao T, Hiraishi T, Yoshimura J, Yajima N, Saito A, et al. Clinical factors predicting outcomes after surgical resection for sporadic cerebellar hemangioblastomas. World Neurosurg. 2014 Nov. 82 (5):815-21.