Herpes

Herpes is the name of a group of viruses that cause painful blisters and sores. The most common viruses are:

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) usually causes cold sores or fever blisters around your mouth. Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) usually causes sores on the genitals or sexual organs (genital herpes). Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection (STI). Once you’re infected, you have the virus for the rest of your life.

- Type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) usually causes oral herpes, fever blisters or cold sores. Type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infects more than half of the U.S. population by the time they reach their 20s. HSV-1 is mainly transmitted via contact with the virus in sores, saliva or surfaces in or around the mouth. People may be exposed to HSV-1 as children due to close skin-to-skin contact with someone infected. Less commonly, HSV-1 can be transmitted to the genital area through oral-genital contact to cause genital herpes. Type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) can be transmitted from oral or skin surfaces that appear normal; however, the greatest risk of transmission is when there are active sores. People who already have HSV-1 are not at risk of reinfection, but they are still at risk of acquiring HSV-2.

- Type 2 herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) usually affects the genital area. Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) usually causes sores on the genitals or sexual organs (genital herpes). Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted infection (STI). HSV-2 is mainly transmitted during sex through contact with genital or anal surfaces, skin, sores or fluids of someone infected with the virus. HSV-2 can be transmitted even if the skin looks normal and is often transmitted in the absence of symptoms.

- However, either HSV-1 or HSV-2 can affect almost any area of skin or mucous membrane. Once you’re infected, you have the virus for the rest of your life.

- Recurrent outbreaks of genital herpes caused by HSV-1 are often less frequent than outbreaks caused by HSV-2.

- In rare circumstances, herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2) can be transmitted from mother to child during delivery, causing neonatal herpes.

- Herpes zoster also known as varicella zoster virus (VZV) or herpesvirus 3, the same virus that causes chickenpox initially and later on shingles. After a person recovers from chickenpox, the varicella zoster virus (VZV) stays dormant (inactive) in the body inside the nerves within dorsal root ganglia of your spinal cord. The varicella zoster virus (VZV) can reactivate years later, causing shingles.

Once you have been infected with the herpes virus, you’ll go through different stages of infection.

- Primary stage. This stage starts 2 to 8 days after you’re infected with the herpes virus. Usually, the herpes virus infection causes groups of small, painful blisters. The fluid in the blisters may be clear or cloudy. The area under the blisters will be red. The blisters break open and become open sores. You may not notice the blisters, or they may be painful. It may hurt to urinate during this stage. While most people have a painful primary stage of infection, some don’t have any symptoms. They may not even know they’re infected.

- Latent stage. During this stage, there are no blisters, sores, or other symptoms. The herpes virus is traveling from your skin into the nerves near your spine where they stay dormant.

- Shedding stage. In the shedding stage, the herpes virus starts multiplying in the nerve endings. If these nerve endings are in areas of your body that make or are in contact with body fluids, the herpes virus can get into those body fluids. This could include saliva, semen, or vaginal fluids. There are no symptoms during this stage, but the herpes virus can be spread during this time. This means that herpes is very contagious during this stage.

- Recurrences. Many people have blisters and sores that come back after the first herpes attack goes away. This is called a recurrence. Usually, the symptoms aren’t as bad as they were during the first attack. Stress, being sick, or being tired may start a recurrence. Being in the sun or having your menstrual period may also cause a recurrence. You may know a recurrence is about to happen if you feel itching, tingling, or pain in the places where you were first infected.

Herpes key facts:

- Genital herpes is a common sexually transmitted infection (STI).

- Over the past 20 years, HSV-1 and HSV-2 estimated seroprevalence has steadily declined, yet certain populations remain disproportionately affected by HSV infection.

- Infection is lifelong; currently, there is no cure for HSV infection.

- Neonatal herpes infection (birth-acquired herpes or herpes during pregnancy) is uncommon yet can result in substantial morbidity and mortality.

If you think you have herpes, see your doctor as soon as possible. It’s easier to diagnose when there are sores. You can start treatment sooner and perhaps have less pain with the infection.

There’s no cure for herpes. But medicines can help. They may be provided as a pill, cream, or a shot. Medicines such as acyclovir and valacyclovir fight the herpes virus. They can speed up healing and lessen the pain of herpes for many people. They can be used to treat a primary outbreak or a recurrent one.

If the medicines are being used to treat a recurrence, they should be started as soon as you feel tingling, burning, or itching. They can also be taken every day to prevent recurrences.

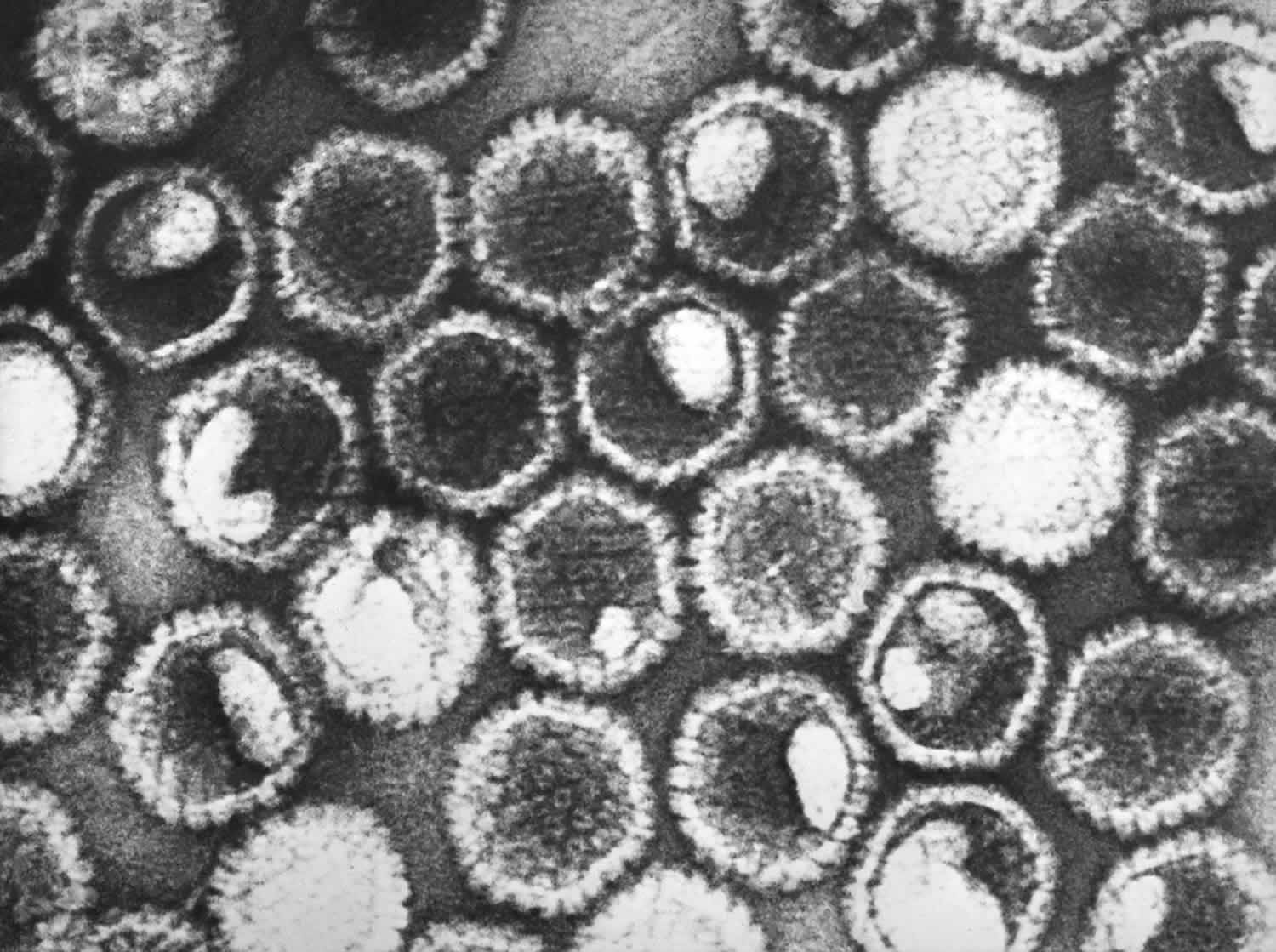

Figure 1. Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

Footnote: This negatively stained transmission electron microscopic image revealed the presence of numerous herpes simplex virions. At the core of its icosahedral proteinaceous capsid, the HSV contains a double-stranded DNA linear genome.

[Source 1 ]What causes herpes?

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by two types of herpes viruses – herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) 2. People with HSV infections can pass along the virus even when they have no visible symptoms.

Herpes is most easily spread when blisters or sores can be seen on the infected person. But it can be spread at any time, even when the person who has herpes isn’t experiencing any symptoms. Herpes can also be spread from one place on your body to another. If you touch sores on your genitals, you can carry the virus on your fingers. Then you can pass it onto other parts of your body, including your mouth or eyes.

The herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) that causes genital herpes is usually spread from one person to another during vaginal, oral, or anal sex. The herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) can enter your body through a break in your skin. It can also enter through the skin of your mouth, penis, vagina, urinary tract opening, or anus.

Herpes simplex 1

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a version of the virus that causes cold sores or fever blisters. People may be exposed to HSV-1 as children due to close skin-to-skin contact with someone infected.

A person with HSV-1 in tissues of the mouth can pass the virus to the genitals of a sexual partner during oral sex. The newly caught infection is a genital herpes infection.

Recurrent outbreaks of genital herpes caused by HSV-1 are often less frequent than outbreaks caused by HSV-2.

Neither HSV-1 nor HSV-2 survives well at room temperature. So the virus is not likely to spread through surfaces, such as a faucet handle or a towel. But kissing or sharing a drinking glass or silverware might spread the virus.

Herpes simplex 2

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is the most common cause of genital herpes. The virus can be present:

- On blisters and ulcers or the fluid from ulcers

- The moist lining or fluids of the mouth

- The moist lining or fluids of the vagina or rectum

The virus moves from one person to another during sexual activity.

Herpes symptoms

Many people who get herpes never have symptoms. Sometimes the symptoms are mild and are mistaken for another skin condition. Symptoms of genital herpes may include:

- Painful sores in the genital area, anus, buttocks, or thighs

- Itching

- Painful urination

- Vaginal discharge

- Tender lumps in the groin

During the first outbreak called primary herpes, you may experience flu-like symptoms. These include body aches, fever, and headache. Many people who have a herpes infection will have outbreaks of sores and symptoms from time to time. Symptoms are usually less severe than the primary outbreak. The frequency of outbreaks also tends to decrease over time.

Herpes prevention

The best way to prevent getting herpes is to not have sex with anyone who has the virus. It can be spread even when the person who has it isn’t showing any symptoms. If your partner has herpes, there is no way of knowing for sure that you won’t get it.

If you are infected, there is no time that is completely safe to have sex and not spread herpes. If you have herpes, you must tell your sex partner. You should avoid having sex if you have any sores. Herpes can spread from one person to another very easily when sores are present.

You should use condoms every time you have sex. They can help reduce the risk of spreading herpes. But it’s still possible to spread or get herpes if you’re using a condom.

Herpes testing

Your doctor will do a physical exam and look at the sores. He or she can do a culture of the fluid from a sore and test it for herpes. Blood tests or other tests on the fluid from a blister can also be done.

Herpes treatment

There’s no cure for herpes. But medicines such as acyclovir and valacyclovir can help fight the herpes virus. If you think you have herpes, see your doctor as soon as possible. It’s easier to diagnose when there are sores. You can start treatment sooner and perhaps have less pain with the infection.

Your doctor give you a pill, cream, or a shot. They can speed up healing and lessen the pain of herpes for many people. They can be used to treat a primary outbreak or a recurrent one.

If the medicines are being used to treat a recurrence, they should be started as soon as you feel tingling, burning, or itching. They can also be taken every day to prevent recurrences.

To soothe the pain associated with herpes:

- Take acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin).

- Place lukewarm or cool cloths on the sore place.

- Take lukewarm baths. (A woman may urinate in the tub at the end of the bath if she is having pain urinating. This may help dilute the urine so it doesn’t burn the sores so badly.)

- Keep the area dry and clean.

- Wear cotton underwear.

- Wear loose-fitting clothes.

Living with herpes

It’s common to feel guilty or ashamed when you are diagnosed with herpes. You may feel your sex life is ruined or that someone you thought you could trust has hurt you. You may feel sad or upset. Talk to your family doctor about how you’re feeling.

Keep in mind that herpes is very common. About 1 in 6 adults have it. Herpes may get less severe as time goes by. You can help protect your sex partner by not having sex during outbreaks and by using condoms at other times.

Shingles

Shingles also called herpes zoster or zoster, is a painful blistering rash disease caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV) the same virus that causes chickenpox, that reactivates (wakes up) causing a painful blistering rash. If you’ve ever had chickenpox, you can get shingles. Most cases of chickenpox occur in children under age 15, but older children and adults can get it too. Chickenpox (varicella-zoster virus infection) spreads very easily from one person to another. After the chickenpox clears, the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) stays inside your body inside the nerves within dorsal root ganglia and lie dormant for years. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) may not cause problems for many years. Eventually, it may reactivates (wakes up) and travels along nerve pathways to your skin — producing shingles (herpes zoster) — a painful, blistering rash. But, not everyone who’s had chickenpox will develop shingles. Shingles tends to cause more pain and less itching than chickenpox. As you get older, the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) may reappear as shingles. Although shingles is most common in people over age 50, anyone who has had chickenpox is at risk. Shingles (herpes zoster) often affects people with weak immunity. People with various kinds of cancer have a 40% increased risk of developing shingles. People who have had shingles rarely get it again; the chance of getting a second episode is about 1%.

Almost 1 out of 3 people in the United States will develop shingles in their lifetime. There are an estimated 1 million cases of shingles each year in this country. Anyone who has recovered from chickenpox may develop shingles; even children can get shingles. However, the risk of shingles increases as you get older. About half of all cases occur in people 60 years old or older. Older adults also are more likely to have severe disease.

Shingles can lead to severe nerve pain called postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) that can last for months or years after the rash goes away.

Shingles generally lasts between two and six weeks. Most people get shingles only once, but it is possible to get it two or more times.

There is no cure for shingles. Early treatment with medicines that fight the virus may help. These medicines may also help prevent lingering pain.

- If you think you might have shingles, talk to your doctor as soon as possible. It’s important to see your doctor no later than 3 days after the rash starts. The doctor will confirm whether or not you have shingles and can make a treatment plan. Although there is no cure for shingles, early treatment with drugs that fight the virus can help the blisters dry up faster and limit severe pain. Shingles can often be treated at home. People with shingles rarely need to stay in a hospital.

The risk of getting shingles increases with age. A vaccine can reduce your risk of getting shingles or lessen its effects. Your doctor may recommend getting this vaccine after your 50th birthday or once you reach 60 years of age. There’s another — and maybe even more important — reason for getting the shingles vaccine. If you’ve had chickenpox, you can still get shingles after getting shingles vaccine. The vaccine also lessens your risk of developing serious complications from shingles, such as life-disrupting nerve pain.

The nerve pain can last long after the shingles rash goes away. Some people have this nerve pain, called post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), for many years. The pain can be so bad that it interferes with your everyday life. The shingles vaccine reduces your risk of developing this nerve pain, even more than it reduces your risk of getting shingles.

An anti-viral medicine may also prevent long-lasting nerve pain if your get shingles. It’s most effective when started within 3 days of seeing the rash. The anti-viral medicine can also make shingles symptoms milder and shorter.

- Shingles and chickenpox are caused by the same virus called varicella zoster virus.

- An estimated 1 million people get shingles each year in the United States.

- Anyone who has had chickenpox can get shingles, and you can get shingles at any age.

- Your risk of getting shingles and having more severe pain increases as you get older.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends people age 50 and older get two doses of the shingles vaccine Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine), separated by 2 to 6 months, to protect against shingles and its complications. Adults 19 years and older who have weakened immune systems because of disease or therapy should also get two doses of Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine), as they have a higher risk of getting shingles and related complications.

Figure 2. Shingles blisters (typical early onset of herpes zoster or shingles rash with blisters in groups)

Figure 3. Shingles rash

Figure 4. Shingles rash on body – typical of herpes zoster or shingles, this image display grouped blisters with central depressions in a red, band-like distribution.

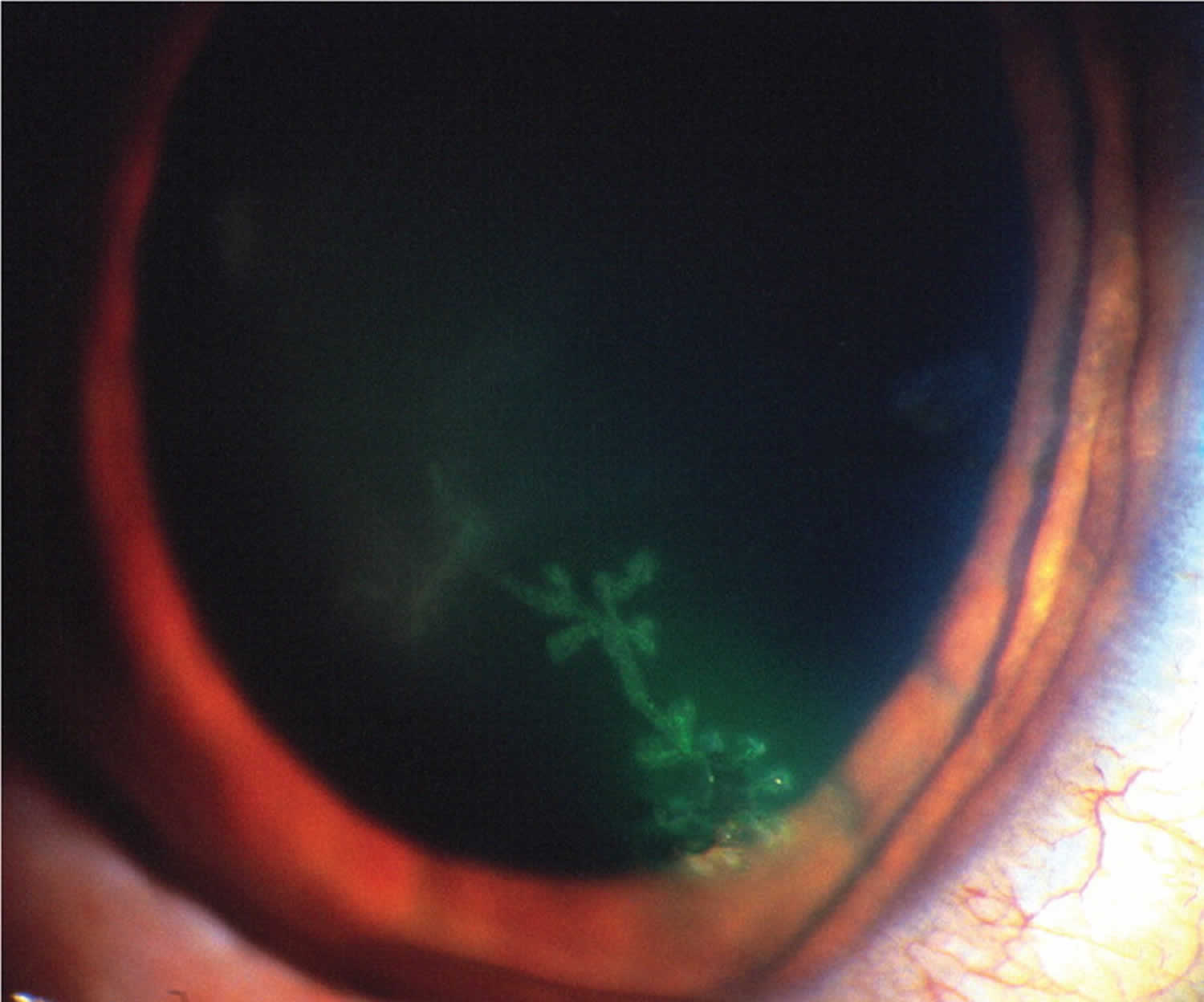

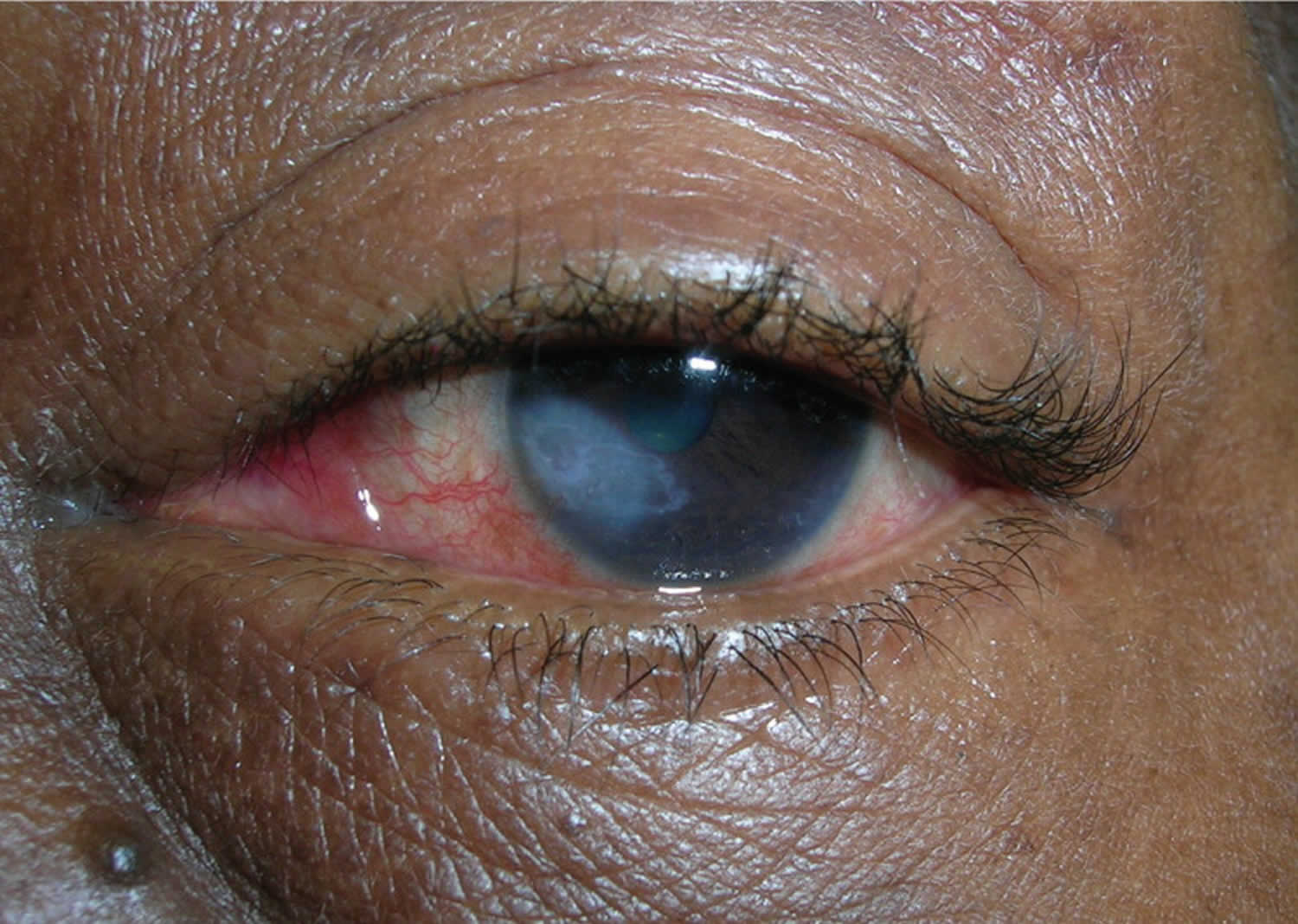

Figure 5. Shingles on face

Footnote: Shingles rash along the face or brow area may involve the eye. The varicella-zoster virus can travel through the nerve fibers and emerge in the cornea. Eye pain, redness, tearing, and blurring are common symptoms of ocular shingles. If this happens, your eye care professional may prescribe oral anti-viral treatment to reduce the risk of inflammation and scarring in the cornea. Shingles can also cause decreased sensitivity in the cornea. Corneal problems may arise months after the shingles are gone from the rest of the body. If you experience shingles in your eye, or nose, or on your face, it’s important to have your eyes examined several months after the shingles have cleared. If left untreated, this infection can lead to permanent eye damage.

You can’t catch shingles from someone. However, if you have a shingles rash, you can pass the virus to someone who has not had chickenpox (or the chickenpox vaccine) can get this virus. This would usually be a child, when this happens, the person develops chickenpox, not shingles. The virus spreads through direct contact with the rash and cannot spread through the air. Chickenpox can be dangerous for some people. Until your shingles blisters scab over, you are contagious and should avoid physical contact with anyone who hasn’t yet had chickenpox or the chickenpox vaccine, especially people with weakened immune systems, pregnant women and newborns.

If you have shingles, what can you do to prevent spreading the virus?

When you have shingles, you’re only contagious while you have blisters. To prevent spreading the virus while you have blisters, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that you:

- Cover the rash

- Wash your hands often and try to avoid touching the rash

- Avoid being around people for whom catching the virus could be dangerous

The varicella-zoster virus is especially dangerous for these people

- Catching this virus and getting chickenpox can be dangerous for women who are pregnant and have not had chickenpox or gotten the chickenpox vaccine. In this situation, the virus can harm the woman’s unborn baby.

Babies less than 1 month old and people who have a weak immune system can also have complications if they catch the virus. People who have a weak immune system include those who are:

- HIV positive

- Taking medicine that weakens their immune system

- Receiving chemotherapy or radiation treatments

You’re not contagious before you develop blisters or after the blisters scab over. Be sure to take precautions while you have blisters.

A person must have had chickenpox to get shingles. Some people who have had chickenpox have a higher risk of getting shingles. But, not everyone who’s had chickenpox will develop shingles.

Most people who develop shingles have only one episode during their lifetime. However, a person can have a second or even a third episode.

- One out of every three people 60 years old or older will get shingles.

- One out of six people older than 60 years who get shingles will have severe pain. The pain can last for months or even years.

- The most common complication of shingles is severe pain where the shingles rash was. This pain can be debilitating. There is no treatment or cure from this pain. As people get older, they are more likely to develop long-term pain as a complication of shingles and the pain is likely to be more severe.

- Shingles may also lead to serious complications involving the eye.

- Very rarely, shingles can also lead to pneumonia, hearing problems, blindness, brain inflammation (encephalitis), or death.

Some illnesses and medical treatments can weaken a person’s immune system and increase the risk of getting shingles. These include:

- Are 50 years of age or older

- Have an illness or injury

- Are under great stress

- Have medical conditions that keep their immune systems from working properly:

- Cancers like leukemia and lymphoma

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS

- Some cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiation

- Medicine taken to prevent rejection of a transplanted organ. Immunosuppressive drugs, such as steroids and drugs that are given after organ transplantation.

- Cortisone when taken for a long time

What causes shingles?

Shingles is caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), the same virus that causes chickenpox. After a person recovers from chickenpox, the virus stays dormant (inactive) in the body (in the nervous system). Shingles appears when the virus wakes up. Scientists aren’t sure why the virus can reactivates or “wakes up” years later, causing shingles. A short-term weakness in immunity may cause this. Shingles is more common in older adults and in people who have weakened immune systems.

Shingles cannot be passed from one person to another. However, the virus that causes shingles, the varicella zoster virus (VZV), can spread from a person with active shingles to cause chickenpox in someone who had never had chickenpox or received chickenpox vaccine.

The varicella zoster virus (VZV) is spread through direct contact with fluid from the rash blisters caused by shingles.

A person with active shingles can spread the virus when the rash is in the blister-phase. A person is not infectious before the blisters appear. Once the rash has developed crusts, the person is no longer infectious.

Shingles is less contagious than chickenpox and the risk of a person with shingles spreading the virus is low if the rash is covered.

If you have shingles, you should:

- Cover the rash.

- Avoid touching or scratching the rash.

- Wash your hands often to prevent the spread of varicella zoster virus.

- Avoid contact with the people below until your rash has developed crusts

- pregnant women who have never had chickenpox or the chickenpox vaccine;

- premature or low birth weight infants; and

- people with weakened immune systems, such as people receiving immunosuppressive medications or undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, and people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Risk factors for shingles

Anyone who has ever had chickenpox can develop shingles. Most adults in the United States had chickenpox when they were children, before the advent of the routine childhood vaccination that now protects against chickenpox.

Factors that may increase your risk of developing shingles include:

- Being older than 50. Shingles is most common in people older than 50. The risk increases with age. Some experts estimate that half the people age 80 and older will have shingles.

- Having certain diseases. Diseases that weaken your immune system, such as HIV/AIDS and cancer, can increase your risk of shingles.

- Undergoing cancer treatments. Radiation or chemotherapy can lower your resistance to diseases and may trigger shingles.

- Taking certain medications. Drugs designed to prevent rejection of transplanted organs can increase your risk of shingles — as can prolonged use of steroids, such as prednisone.

Triggering factors for shingles

Shingles triggering factors are sometimes recognized, such as:

- Pressure on the nerve roots

- Radiotherapy at the level of the affected nerve root

- Spinal surgery

- An infection

- An injury (not necessarily to the spine)

- Contact with someone with varicella (chickenpox) or herpes zoster (shingles)

Shingles prevention

A shingles vaccine may help prevent shingles. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends people age 50 and older get two doses of the shingles vaccine Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine), separated by 2 to 6 months, to protect against shingles and its complications. Adults 19 years and older who have weakened immune systems because of disease or therapy should also get two doses of Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine), as they have a higher risk of getting shingles and related complications.

Routine vaccination of people 50 years old and older 5:

- Whether or not they report a prior episode of herpes zoster.

- Whether or not they report a prior dose of Zostavax, a shingles vaccine that is no longer available for use in the United States.

- It is not necessary to screen, either verbally or by laboratory serology, for evidence of prior varicella.

In the United States, Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017. Studies suggest that Shingrix offers protection against shingles for more than five years. Shingrix is a nonliving vaccine made of a virus component. It is given in two doses, with 2-6 months between doses.

The shingles vaccine is used only as a prevention strategy. It’s not intended to treat people who currently have the disease. Talk to your doctor about which option is right for you.

Shingrix is approved and recommended for people age 50 and older, including those who’ve previously received the Zostavax vaccine or had shingles.

- The Zostavax vaccine is no longer sold in the U.S., but other countries may still use it.

The most common side effects of either shingles vaccine are redness, pain, tenderness, swelling and itching at the injection site, and headaches.

The shingles vaccine doesn’t guarantee that you won’t get shingles. But this vaccine will likely reduce the course and severity of the disease and reduce your risk of postherpetic neuralgia.

Adults 50 years old or older should talk to their healthcare professional about getting two doses of the shingles vaccine Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine), separated by 2 to 6 months, to protect against shingles and its complications.

- The shingles vaccine can reduce your risk of shingles and the long-term pain it can cause 6.

- Persons who have already had shingles or who have a chronic medical condition can receive the shingles vaccine.

- In a clinical trial involving thousands of adults 60 years old or older, the vaccine reduced the risk of shingles by about half. Even if the shingles vaccine doesn’t prevent you from getting shingles, it can still reduce the chance of having long-term pain or post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Talk with your healthcare professional for more information and to find out if the shingles vaccine is right for you.

Adults can get vaccines at doctors’ offices, pharmacies, workplaces, community health clinics, and health departments. To find a place to get a vaccine near you, go to https://vaccinefinder.org/

Most private health insurance plans cover recommended vaccines. Check with your insurance provider for details and for a list of vaccine providers. Medicare Part D plans cover shingles vaccine, but there may be costs to you depending on your specific plan.

If you do not have health insurance, visit https://www.healthcare.gov/ to learn more about health insurance options.

Contraindications and precautions for herpes zoster vaccination

Shingrix (recombinant zoster vaccine) should NOT be administered to 5, 7:

- A person with a history of severe allergic reaction, such as anaphylaxis, to any component of this vaccine.

- A person experiencing an acute episode of herpes zoster. Shingrix is not a treatment for herpes zoster or postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). The general guidance for any vaccine is to wait until the acute stage of the illness is over and symptoms abate.

There is currently no CDC recommendation for Shingrix use in pregnancy; therefore, providers should consider delaying vaccination until after pregnancy. There is no recommendation for pregnancy testing before vaccination with Shingrix. Recombinant vaccines such as Shingrix pose no known risk to people who are breastfeeding or to their infants. Providers may consider vaccination without regard to breastfeeding status if Shingrix is otherwise indicated.

Adults with a minor acute illness, such as a cold, can receive Shingrix. Adults with a moderate or severe acute illness should usually wait until they recover before getting the vaccine.

Shingles signs and symptoms

Early signs of shingles include burning or shooting pain and tingling or itching, usually on one side of the body or face. The most common place for shingles is a band that goes around one side of your waistline. The pain can be mild to severe. Rashes or blisters appear anywhere from one to 14 days later. The rash consists of blisters that typically scab over in 7 to 10 days. The rash usually clears up within 2 to 4 weeks. If shingles appears on your face, it may affect your vision or hearing. The pain of shingles may last for weeks, months, or even years after the blisters have healed.

- The warning: Before the rash develops, people often have pain, itching, burning or tingling in the area where the rash will develop. And area of skin may feel very sensitive. This usually occurs in a small area on 1 side of the body. These symptoms can come and go or be constant. The lymph nodes draining the affected area are often enlarged and tender. Most people experience this for 1 to 5 days before the rash appears. It can last longer.

- Rash: A rash then appears in the same area. Most commonly, the rash occurs in a single stripe around either the left or the right side of the body. In other cases, the rash occurs on one side of the face. In rare cases (usually among people with weakened immune systems), the rash may be more widespread and look similar to a chickenpox rash. Shingles can affect the eye and cause loss of vision.

- Blisters: The rash soon turns into groups of clear blisters. The blisters turn yellow or bloody before they crust over (scab) and heal. The blisters tend to last 2 to 3 weeks.

- Pain: It is uncommon to have blisters without pain. Once the blisters heal, the pain tends to lessen. The pain can last for months after the blisters clear.

- Flu-like symptoms: The person may get a fever, headache, chills or upset stomach with the rash.

The chest (thoracic), neck (cervical), forehead (ophthalmic) and lumbar or sacral sensory nerve supply regions are most commonly affected at all ages. The frequency of ophthalmic herpes zoster or herpes zoster ophthalmicus (shingles affecting the eye) increases with age. Herpes zoster occasionally causes blisters inside the mouth or ears, and can also affect the genital area. Sometimes there is pain without rash—herpes zoster “sine eruptione”—or rash without pain, most often in children.

Pain and general symptoms subside gradually as the eruption disappears. In uncomplicated cases, recovery is complete within 2–3 weeks in children and young adults, and within 3–4 weeks in older patients.

Complications of shingles

The most common complication of shingles is a condition called post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). People with post-herpetic neuralgia have severe pain in the areas where they had the shingles rash, even after the rash clears up. Post-herpetic neuralgia is diagnosed in people who have pain that persists after their rash has resolved. Some define post-herpetic neuralgia as any duration of pain after the rash resolves; others define it as duration of pain for more than 30 days, or for more than 90 days after rash onset.

The pain from post-herpetic neuralgia may be severe and debilitating, but it usually resolves in a few weeks or months. Some people can have pain from post-herpetic neuralgia for many years and can interfere with daily life.

A person’s risk of having post-herpetic neuralgia after herpes zoster increases with age. As people get older, they are more likely to develop post-herpetic neuralgia, and the pain is more likely to be severe. Post-herpetic neuralgia occurs rarely among people under 40 years of age but can occur in approximately 13% (and possibly more) of untreated people who are 60 years of age and older with herpes zoster. Older adults are more likely to have post-herpetic neuralgia and to have longer lasting and more severe pain. Other predictors of post-herpetic neuralgia include the level of pain a person has when they have the rash and the size of their rash.

Other complications of herpes zoster include:

- Shingles may also lead to serious complications involving the eye (herpes zoster ophthalmicus, when the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve is involved) may result in vision loss.

- Bacterial superinfection of the lesions, usually due to Staphylococcus aureus and, less commonly, due to group A beta hemolytic streptococcus.

- Cranial and peripheral nerve palsies. Depending on which nerves are affected, shingles can cause an inflammation of the brain (encephalitis), facial paralysis, or hearing or balance problems. Muscle weakness in about one in 20 patients. Facial nerve palsy is the most common result (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). There is a 50% chance of complete recovery, but some improvement can be expected in nearly all cases

- Deep blisters that take weeks to heal followed by scarring.

- Very rarely, shingles can also lead to pneumonia, hearing problems, blindness, brain inflammation (meningoencephalitis), hepatitis, acute retinal necrosis or death.

People with compromised or suppressed immune systems are more likely to have complications from herpes zoster. They are more likely to have severe rash that lasts longer. Also, they are at increased risk of developing disseminated herpes zoster.

Shingles (herpes zoster) in the early months of pregnancy can harm the fetus, but luckily this is rare. Shingles in late pregnancy can cause chickenpox in the fetus or newborn. Herpes zoster may then develop as an infant.

Shingles diagnosis

Shingles is usually diagnosed based on the history of pain on one side of your body, along with the telltale rash and blisters. Your doctor may also take a tissue scraping or culture of the blisters for examination in the laboratory.

Shingles treatment

There’s no cure for shingles, but prompt treatment with prescription antiviral drugs can speed healing and reduce your risk of complications. These medications include:

- Acyclovir (Zovirax)

- Valacyclovir (Valtrex)

- Famciclovir

Antiviral treatment can reduce pain and the duration of symptoms if started within one to three days after the onset of herpes zoster. Aciclovir 800 mg 5 times daily for seven days is most often prescribed. Valaciclovir and famciclovir are also useful.

In healthy children shingles is often relatively mild and may not require treatment, however, children who take courses of systemic steroids, e.g., for asthma, are rendered vulnerable for up to three months after treatment is complete – if the child develops chickenpox in this period parents should seek urgent competent advice as treatment with oral antiviral therapy will be required.

Immunocompromised patients

- Should continue on with oral antiviral therapy for two days after crusting of the lesions

- If the patient is unwell / develops widespread (disseminated) zoster, hospital admission will be needed

Management of acute herpes zoster may include:

- Rest and pain relief

- Protective ointment applied to the rash, such as petroleum jelly.

- Oral antibiotics for secondary infection

Shingles can cause severe pain, so your doctor also may prescribe:

- Capsaicin topical patch (Qutenza)

- Anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin (Neurontin)

- Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline

- Numbing agents, such as lidocaine, delivered via a cream, gel, spray or skin patch

- Medications that contain narcotics, such as codeine

- An injection including corticosteroids and local anesthetics

Shingles generally lasts between two and six weeks. Most people get shingles only once, but it is possible to get it two or more times.

Shingles medication

It is best to get treatment immediately. Treatment can include:

Pain relievers to help ease the pain: The pain can be very bad, and prescription painkillers may be necessary. Your doctor also may prescribe:

- Capsaicin topical patch (Qutenza)

- Anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin (Neurontin)

- Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline

- Numbing agents, such as lidocaine, delivered via a cream, gel, spray or skin patch

- Medications that contain narcotics, such as codeine

- An injection including corticosteroids and local anesthetics

Post-herpetic neuralgia may be difficult to treat successfully. It may respond to any of the following.

- Local anesthetic applications

- Topical capsaicin

- Tricyclic antidepressant medications such as amitriptyline

- Anti-epileptic medications gabapentin and pregabalin

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation or acupuncture

- Botulinum toxin into the affected area

- Early use of antiviral medication

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and opioids are generally unhelpful.

Anti-viral medicine: This medicine may be prescribed when a doctor diagnoses shingles within 72 hours of the rash first appearing. The earlier anti-viral treatment is started, the better it works. Anti-viral medicines include famciclovir, valacyclovir, and acyclovir. These can lessen the pain and the amount of time the pain lasts.

Nerve blocks: Given for intense pain, these injections (shots) contain a numbing anesthetic and sometimes a corticosteroid.

Corticosteroids: To lower swelling and pain, some patients may get corticosteroid pills with their anti-viral medicine. This treatment is not common because it can make the rash spread.

Treatments for pain after the rash clears: Certain anti-depressants, pain relievers, anesthetic creams and patches, and anti-seizure medicines can help.

Ophthalmic zoster

- All patients with ophthalmic zoster, irrespective of age or severity of symptoms, should be prescribed oral antiviral drugs at the first sign of disease

- Patients with a red eye or visual complaints must be referred to an ophthalmologist on an urgent basis

- Those not needing referral must be reviewed after at most one week

Ramsay-Hunt syndrome

- Oral antiviral therapy must be started immediately and contact the on-call ENT (ear nose and throat) specialist

- Some advocate the use of systemic steroids – refer to local guidelines for management

Home remedies for shingles

- Get plenty of rest and eat well-balanced meals.

- Try simple exercises like stretching or walking. Check with your doctor before starting a new exercise routine.

- Apply a cool washcloth to your blisters to ease the pain and help dry the blisters.

- Cool compresses, baths or ice packs may help with the discomfort. Do not apply ice packs directly to the skin. Wrap the ice pack in a light towel and place it gently over the dressing. Wash the towel in hot water after use.

- Apply calamine lotion to the blisters.

- Cover the rash with loose, non-stick, sterile bandages.

- Wear loose cotton clothes around the body parts that hurt.

- Do things that take your mind off your pain. For example, watch TV, read, talk with friends, listen to relaxing music, or work on a hobby you like.

- Avoid stress. It can make the pain worse.

- Try not to scratch the rash. Scratching may cause scarring and infection of the blisters.

- If the blisters are open, applying creams or gels is not recommended because they might increase the risk of a secondary bacterial infection.

- After a bath or shower, gently pat yourself dry with a clean towel. Do not rub or use the towel to scratch yourself and do not share towels.

- Do not use antibiotic creams or sticking plasters on the blisters since they may slow down the healing process.

- Take an oatmeal bath or use calamine lotion to see if it soothes your skin.

- Avoid contact with people who may be more at risk, such as pregnant women who are not immune to chickenpox, people who have a weak immune system and babies less than 1 month old.

- Do not share towels, play contact sports, or go swimming.

- Share your feelings about your pain with family and friends. Ask for their understanding.

Also, you can limit spreading the virus by:

- Keeping the rash covered

- Not touching or scratching the rash

- Washing your hands often

Shingles prognosis

Most cases of shingles last 3 to 5 weeks. Shingles follows a pattern:

- The first sign is often burning or tingling pain; sometimes, it includes numbness or itching on one side of the body.

- Somewhere between 1 and 5 days after the tingling or burning feeling on the skin, a red rash will appear.

- A few days later, the rash will turn into fluid-filled blisters.

- About a week to 10 days after that, the blisters dry up and crust over.

- A couple of weeks later, the scabs clear up.

Most people get shingles only one time. But, it is possible to have it more than once.

Longterm pain and other lasting problems

After the shingles rash goes away, some people may be left with ongoing pain called post-herpetic neuralgia or PHN. The pain is felt in the area where the rash had been. For some people, post-herpetic neuralgia is the longest lasting and worst part of shingles. The older you are when you get shingles, the greater your chance of developing post-herpetic neuralgia.

The post-herpetic neuralgia pain can cause depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, and weight loss. Some people with post-herpetic neuralgia find it hard to go about their daily activities, like dressing, cooking, and eating. Talk with your doctor if you have any of these problems.

There are medicines that may help with post-herpetic neuralgia. Steroids may lessen the pain and shorten the time you’re sick. Analgesics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants may also reduce the pain. Usually, post-herpetic neuralgia will get better over time.

Some people have other problems that last after shingles has cleared up. For example, the blisters caused by shingles can become infected. They may also leave a scar. It is important to keep the area clean and try not to scratch the blisters. Your doctor can prescribe an antibiotic treatment if needed.

See your doctor right away if you notice blisters on your face—this is an urgent problem. Blisters near or in the eye can cause lasting eye damage or blindness. Hearing loss, a brief paralysis of the face, or, very rarely, swelling of the brain (encephalitis) can also occur.

Herpes and pregnancy

Newborn infants can become infected with herpes virus during pregnancy, during labor or delivery, or after birth. Herpes type 2 virus (genital herpes) is the most common cause of herpes infection in newborn babies. But herpes type 1 virus (oral herpes) can also occur.

Newborn infants can become infected with herpes virus:

- In the uterus (this is unusual)

- Passing through the birth canal (birth-acquired herpes, the most common method of infection)

- Right after birth (postpartum) from being kissed or having other contact with someone who has herpes mouth sores

If the mother has an active outbreak of genital herpes at the time of delivery, the baby is more likely to become infected during birth. Some mothers may not know they have herpes sores inside their vagina.

Some women have had herpes infections in the past, but are not aware of it, and may pass the virus to their baby.

If your baby has any symptoms of birth-acquired herpes, including skin blisters with no other symptoms, have the baby seen by your doctor right away.

It’s important to avoid getting herpes during pregnancy. If your partner has herpes and you don’t have it, be sure to always use condoms during sexual intercourse. Your partner could pass the infection to you even if they are not currently experiencing an outbreak. If there are visible sores, avoid having sex completely until the sores have healed.

If you’re pregnant and have genital herpes, or if you have ever had sex with someone who had it, tell her doctor. Your doctor will give you an antiviral medicine to start taking toward the end of your pregnancy. This will make it less likely that you will have an outbreak at or near the time you deliver your baby.

If you have an active genital herpes infection at or near the time of delivery, you can pass it to your baby. When the baby passes through the birth canal, it may come in contact with sores and become infected with the virus. This can cause brain damage, blindness, or even death in newborns.

If you do have an outbreak of genital herpes at the time of delivery, your doctor will most likely deliver your baby by C-section. With a C-section, the baby won’t go through the birth canal and be exposed to the virus. This lessens the risk of giving herpes to your baby.

Herpes and pregnancy causes

Newborn infants can become infected with herpes virus during pregnancy, during labor or delivery, or after birth during the first 28 days after birth 8. Herpes type 2 virus (genital herpes) is the most common cause of herpes infection in newborn babies. But herpes type 1 virus (oral herpes) can also occur. Neonatal HSV infrequently occurs, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 3,000 deliveries 8, 9. In the United States, however, HSV-related neonatal deaths increased significantly between 1995 and 2017 10.

Newborn infants can become infected with herpes virus:

- In the uterus (this is unusual)

- Passing through the birth canal (birth-acquired herpes, the most common method of infection) also called intrapartum infection

- Right after birth (postpartum) from being kissed or having other contact with someone who has herpes mouth sores

The following five factors have been identified as the major influence for risk of transmission 11:

- Whether the HSV infection is primary or recurrent

- HSV antibody status of the pregnant person

- Duration of membrane rupture

- Integrity of mucocutaneous barrier (e.g. use of fetal scalp electrodes)

- Mode of the delivery (vaginal versus cesarean)

Approximately 85% of neonatal HSV infections result from intrapartum infection (a period from the onset of labor through delivery of the placenta), with the remaining cases involving HSV exposure and transmission during the intrauterine (in utero) or postpartum (postnatal) periods 11. The risk of intrapartum HSV transmission is highest among pregnant persons who newly acquire genital HSV-2 (or HSV-1) late in pregnancy when compared to women who have reactivation of genital HSV during pregnancy 8.

If the mother has an active outbreak of genital herpes at the time of delivery, the baby is more likely to become infected during birth. Some mothers may not know they have herpes sores inside their vagina.

The highest HSV transmission risk occurs when a pregnant person acquires HSV near the time of delivery 12, 13, 14. If a pregnant woman has primary genital HSV infection and is shedding HSV at the time of delivery, the risk of HSV transmission to the neonate is 10 to 30 times higher than if they are shedding HSV during a recurrent episode of genital herpes 11.

Some women have had herpes infections in the past, but are not aware of it, and may pass the virus to their baby.

If your baby has any symptoms of birth-acquired herpes, including skin blisters with no other symptoms, have the baby seen by your doctor right away.

Herpes and pregnancy prevention

Practicing safe sex can help prevent the mother from getting genital herpes.

People with cold sores (oral herpes) should not come in contact with newborn infants. To prevent transmitting the virus, caregivers who have a cold sore should wear a mask and wash their hands carefully before coming in contact with an infant.

Mothers should speak to their doctors about the best way to minimize the risk of transmitting herpes to their infant.

Herpes and pregnancy symptoms

Herpes may only appear as a skin infection. Small, fluid-filled blisters (vesicles) may appear. These blisters break, crust over, and finally heal. A mild scar may remain. Herpes infection may also spread throughout your body. This is called disseminated herpes. In this type, the herpes virus can affect many parts of your body.

- Herpes infection in the brain is called herpes encephalitis

- The liver, lungs, and kidneys may also be involved

- There may or may not be blisters on the skin

Newborn infants with herpes that has spread to the brain or other parts of the body are often very sick. Symptoms include:

- Skin sores, fluid-filled blisters

- Bleeding easily

- Breathing difficulties such as rapid breathing and short periods without breathing, which can lead to nostril flaring, grunting, or blue appearance

- Yellow skin and whites of the eyes

- Weakness

- Low body temperature (hypothermia)

- Poor feeding

- Seizures, shock, or coma

Herpes that is caught shortly after birth has symptoms similar to those of birth-acquired herpes.

Herpes the baby gets in the uterus can cause:

- Eye disease, such as inflammation of the retina (chorioretinitis)

- Severe brain damage

- Skin sores (lesions)

Herpes and pregnancy diagnosis

Tests for birth-acquired herpes include:

- Checking for the virus by scraping from vesicle or vesicle culture

- Electroencephalogram (EEG)

- MRI of the head

- Spinal fluid culture

Additional tests that may be done if the baby is very sick include:

- Blood gas analysis

- Blood coagulation studies (PT, PTT)

- Complete blood count

- Electrolyte measurements

- Tests of liver function

Herpes and pregnancy treatment

It is important to tell your doctor at your first prenatal visit if you have a history of genital herpes.

- If you have frequent herpes outbreaks, you’ll be given a medicine to take during the last month of pregnancy to treat the virus. This helps prevent an outbreak at the time of delivery.

- C-section is recommended for pregnant women who have an active outbreak of herpes sores and are in labor.

- You may have some prodromal symptoms before a sore appears. You may experience itching in the affected area, “tingling” or “pinching” sensations, muscle tenderness, shooting pains in the buttocks, legs, or groin, and nerve pain in the leg. Be sure to notify your provider if you are having these sensations.

- For women with a first-episode genital herpes infection during the third trimester of pregnancy, C-section may be offered due to the possibility of prolonged viral shedding.

Herpes virus infection in infants is generally treated with antiviral medicine given through a vein (intravenous). The baby may need to be on the medicine for several weeks.

Treatment may also be needed for the effects of herpes infection, such as shock or seizures. Because these babies are very ill, treatment is often done in the hospital intensive care unit.

Management of babies with herpes

Infants with HSV disease should be treated with parenteral acyclovir therapy in consultation with a pediatric infectious diseases specialist. Treatment duration is generally 14 days for SEM disease or 21 days for disseminated and central nervous system disease, and suppressive therapy after central nervous system disease may be indicated for up to 6 months; detailed guidelines are available for management of neonates who are delivered vaginally in the presence of maternal genital HSV lesions 15, 16. Despite improvement in outcomes with parenteral acyclovir and subsequent suppressive oral acyclovir therapy, neurodevelopmental outcomes remain poor in neonates with central nervous system herpes if present at birth 16, 17:

Recommended treatment regimen of neonatal herpes for infants with neonatal herpes limited to the skin and mucous membranes:

- Acyclovir 20 mg/kg body weight IV every 8 hours for 14 days

Recommended regimen for infants with neonatal herpes who have disseminated disease and disease involving the brain and spinal cord (CNS):

- Acyclovir 20 mg/kg body weight IV every 8 hours for 21 days

Herpes and pregnancy prognosis

Infants with systemic herpes or encephalitis often do poorly. This is despite antiviral medicines and early treatment.

In infants with skin disease, the vesicles may keep coming back, even after treatment is finished.

Affected children may have developmental delay and learning disabilities.

Genital herpes

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by two types of herpes viruses – herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) 18, 2. Genital herpes is a chronic, lifelong viral infection that causes recurrent genital ulcers and on rare occasions, disseminated and visceral disease 19. Most people with genital herpes do not know they have it or may have very mild symptoms. Other people have pain, itching and sores around their genitals, anus or mouth. People with genital herpes are able to spread the virus despite having very mild symptoms or no symptoms. Genital herpes can often be spread by skin-to-skin contact during vaginal, anal and oral sex.

Genital herpes is common in the United States. At least 50 million people in the United States—about one in six adults—are infected with HSV. More than one out of every six people aged 14 to 49 years have genital herpes. Genital herpes is more common in women than in men.

Genital herpes can cause outbreaks of blisters or sores on the genitals and anus. Once infected, you can continue to have recurrent episodes of symptoms throughout your life.

There are 2 types of herpes simplex virus (HSV), both viruses can affect either the lips, mouth, genital or anal areas, however:

- Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) commonly causes cold sores on the lips, mouth or face. However, most people do not have any symptoms. Most people with oral herpes were infected during childhood or young adulthood from non-sexual contact with saliva. Oral herpes caused by HSV-1 can be spread from the mouth to the genitals through oral sex. This is why some cases of genital herpes are caused by HSV-1.

- Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV2) causes most genital herpes in the United States 20.

Genital herpes is most easily spread when there are blisters or sores, but can still be passed even if a person has no current blisters or sores or other symptoms. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) also can be present on the skin even if there are no sores. If a person comes into contact with the herpes simplex virus (HSV) on an infected person’s skin, he or she can become infected.

In 2018, there were an estimated 18.6 million people age 18-49 years living with genital herpes caused by herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), plus several additional million persons living with genital herpes caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) 21. In 2018 alone, approximately 572,000 persons 18-49 years of age newly acquired HSV-2 in the United States 21. Since genital herpes is not a nationally notifiable condition, the true prevalence (persons living with genital herpes) and incidence (new cases of genital herpes) are difficult to accurately determine.

There is no cure for genital herpes, once you’re infected, you have the virus for the rest of your life. Symptoms often show up again after the first outbreak. Medicine can ease symptoms. It also lowers the risk of infecting others. Condoms can help prevent the spread of a genital herpes infection.

Treatment the first time you have genital herpes

- You may be prescribed antiviral medicine to stop the symptoms getting worse, you need to start taking this within 5 days of the symptoms appearing. You doctor may also give you cream for the pain.

Treatment if the blisters come back

- Go to your doctor or STD clinic if you have been diagnosed with genital herpes and need treatment for an outbreak. Antiviral medicine may help shorten an outbreak by 1 or 2 days if you start taking it as soon as symptoms appear. But outbreaks usually settle by themselves, so you may not need treatment. Recurrent outbreaks are usually milder than the first episode of genital herpes. Over time, outbreaks tend to happen less often and be less severe. Some people never have outbreaks.

- Some people who have more than 6 outbreaks in a year may benefit from taking antiviral medicine for 6 to 12 months. If you still have outbreaks of genital herpes during this time, you may be referred to a specialist.

- If you think you have genital herpes, it is important to see a doctor as soon as possible. Your doctor can confirm the diagnosis with testing and start treatment. Anti-viral medication may help to prevent transmission. Talk to your doctor about this in more detail.

- If you have genital herpes, it is important to always use condoms and dental dams when having sex, even when you have no symptoms. A dental dam is a square of thin latex that can be placed over the vulva or anal area during oral sex. It is safest to avoid sex when you have blisters, sores or symptoms.

- It is also important to tell your sexual partners that you have genital herpes. Your doctor can help you decide who to tell and how to tell them.

- If you’re pregnant: It’s important to tell your obstetrician that you or a partner have had genital herpes, so that they can monitor you for symptoms and manage your pregnancy safely. There is a risk you can pass the virus on to your baby if you have a vaginal delivery during a first attack of genital herpes. If this happens you may be recommended to have a caesarean delivery.

Genital herpes cause

Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by two types of herpes viruses – herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) 2. People with HSV infections can pass along the virus even when they have no visible symptoms.

First-episode genital herpes caused by HSV-1 has been identified with increased frequency among young women, college students, and men who have sex with men 22, 23, 24, 25, 26. Acquisition of genital HSV-1 can occur through genital-genital contact or via receptive oral sex 27, 28. In some settings, such as university campuses, HSV-1 has now replaced HSV-2 as the leading cause of first-episode genital herpes 23. One proposed reason for this shift is decreasing HSV-1 orolabial infection in childhood and early adolescence 25, with first exposure to HSV-1 occurring later in life with sexual activity. Changing sex practices in young adults, namely an increase in oral-genital sex, may also contribute to the changing epidemiology of genital herpes 25. General HSV-1 seroprevalence data, such as reported in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) studies, do not provide accurate information on genital herpes infections, since it is not possible to determine whether infection is oral or genital with a positive HSV-1 serologic test. Nevertheless, HSV-1 does contribute significantly to the burden of genital HSV, and there are likely at least several million prevalent genital HSV-1 infections in the United States 21.

How is genital herpes spread?

You can get genital herpes by having vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone who has the disease, often he/she is unaware that he/she has HSV infection 29, 30, 31.

If you do not have herpes, you can get infected if you come into contact with the herpes virus in 32:

- A herpes sore;

- Saliva (if your partner has an oral herpes infection) or genital secretions (if your partner has a genital herpes infection);

- Skin in the oral area if your partner has an oral herpes infection, or skin in the genital area if your partner has a genital herpes infection.

You can get herpes from a sex partner who does not have a visible sore or who may not know he or she is infected. It is also possible to get genital herpes if you receive oral sex from a sex partner who has oral herpes.

- You will not get herpes from toilet seats, bedding, or swimming pools, or from touching objects around you such as silverware, soap, or towels. If you have additional questions about how herpes is spread, consider discussing your concerns with a healthcare provider.

Risk factors for genital herpes

A higher risk of getting genital herpes is linked to:

- Contact with genitals through oral, vaginal or anal sex. Having sexual contact without using a barrier increases your risk of genital herpes. Barriers include condoms and condom-like protectors called dental dams used during oral sex. Women are at higher risk of getting genital herpes. The virus can spread more easily from men to women than from women to men.

- Having sex with multiple partners. The number of people you have sex with is a strong risk factor. Contact with genitals through sex or sexual activity puts you at higher risk. Most people with genital herpes do not know they have it. Each additional sexual partner raises your risk of being exposed to the virus that causes genital herpes.

- Having a partner who has genital herpes but is not taking medicine to treat it. There is no cure for genital herpes, but medicine can help limit outbreaks.

- Certain groups within the population. Women, people with a history of sexually transmitted diseases, older people, Black people in in the United States and men who have sex with men diagnosed with genital herpes at a higher than average rate. Women are more likely to have genital herpes than are men. The virus is sexually transmitted more easily from men to women than it is from women to men. People in groups at higher risk may choose to talk to a health care provider about their personal risk.

Genital herpes prevention

The only way to avoid sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) is to not have vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

If you are sexually active, you can do the following things to lower your chances of getting genital herpes:

- Be in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who is not infected with an STD (e.g., a partner who has been tested and has negative STD test results);

- Using latex condoms the right way every time you have sex.

Be aware that not all herpes sores occur in areas that are covered by a latex condom. Also, herpes virus can be released (shed) from areas of the skin that do not have a visible herpes sore. For these reasons, condoms may not fully protect you from getting herpes.

If you are in a relationship with a person known to have genital herpes, you can lower your risk of getting genital herpes if:

- Your partner takes an anti-herpes medication every day. This is something your partner should discuss with his or her doctor.

- You avoid having vaginal, anal, or oral sex when your partner has herpes symptoms (i.e., when your partner is having an outbreak).

Genital herpes signs and symptoms

The symptoms of genital herpes can vary widely, depending upon whether you are having an initial or recurrent episode. However, many people infected with genital herpes have no symptoms, or have very mild symptoms.

The first time a person has noticeable signs or symptoms of herpes may not be the initial episode. For example, it is possible to be infected for the first time, have few or no symptoms, and then have a recurrent outbreak with noticeable symptoms several years later. For this reason, it is often difficult to determine when the initial infection occurred, especially if a person has had more than one sexual partner. Thus, a current sexual partner may not be the source of the infection.

- Most people infected with HSV don’t know they have it because they don’t have any signs or symptoms or because their signs and symptoms are so mild.

When present, symptoms may begin about two to 12 days after exposure to the virus. If you experience symptoms of genital herpes, they may include:

- Pain or itching. You may experience pain and tenderness in your genital area until the infection clears.

- Small red bumps or tiny white blisters. These may appear a few days to a few weeks after infection.

- Ulcers. These may form when blisters rupture and ooze or bleed. Ulcers may make it painful to urinate.

- Scabs. Skin will crust over and form scabs as ulcers heal.

During an initial outbreak, you may have flu-like signs and symptoms such as swollen lymph nodes in your groin, headache, muscle aches and fever.

Differences in symptom location

Sores appear where the infection entered your body. You can spread the infection by touching a sore and then rubbing or scratching another area of your body, including your eyes.

Men and women can develop sores on the:

- Buttocks and thighs

- Anus

- Mouth

- Urethra (the tube that allows urine to drain from the bladder to the outside)

Women can also develop sores in or on the:

- Vaginal area

- External genitals

- Cervix

Men can also develop sores in or on the:

- Penis

- Scrotum

Genital herpes complications

Complications associated with genital herpes may include:

- Other sexually transmitted infections. Having genital sores increases your risk of transmitting or contracting other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV and AIDS.

- Newborn infection. Babies born to infected mothers can be exposed to the virus during the birthing process. Less often, the virus is passed during pregnancy or by close contact after delivery. Even with treatment, these newborns have a high risk of brain damage, blindness or death for the newborn.

- Bladder problems. In some cases, the sores associated with genital herpes can cause inflammation around the tube that delivers urine from your bladder to the outside world (urethra). The swelling can close the urethra for several days, requiring the insertion of a catheter to drain your bladder.

- Internal inflammatory disease. HSV infection can cause swelling and inflammation within the organs associated with sexual activity and urination. These include the ureter, rectum, vagina, cervix and uterus.

- Meningitis. In rare instances, HSV infection leads to inflammation of the membranes and cerebrospinal fluid surrounding your brain and spinal cord.

- Rectal inflammation (proctitis). Genital herpes can lead to inflammation of the lining of the rectum, particularly in men who have sex with men.

- Finger infection. An HSV infection can spread to a finger through a break in the skin causing discoloration, swelling and sores. The infections are called herpetic whitlow.

- Eye infection. HSV infection of the eye can cause pain, sores, blurred vision and blindness.

- Swelling of the brain. Rarely, HSV infection leads to inflammation and swelling of the brain, also called encephalitis.

- Infection of internal organs. Rarely, HSV in the bloodstream can cause infections of internal organs.

Persons with HSV-2 infection have a threefold increase in the risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection 33. This may be related to open ulcers, or lymphocytes at the site of eruptions, facilitating HIV invasion during sexual contact 34.

Concurrent infection with HSV-2 and HIV increases the severity of HSV episodes and the likelihood of atypical presentations 35. The relationship between genital HSV-1 and HIV infections has not been well studied 36.

Genital herpes diagnosis

Your doctor usually can diagnose genital herpes based history of your sexual activity, a physical exam and the results of certain laboratory tests:

- Viral culture. This test involves taking a tissue sample or scraping of the sores for examination in the laboratory.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test also called nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). PCR is used to copy your DNA from a sample of your blood, tissue from a sore or spinal fluid. The DNA can then be tested to establish the presence of HSV and determine which type of HSV you have.

- Antigen detection. The use of direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing offers lower sensitivity than viral culture or PCR and is not recommended 37.

- Cytologic examination: Cells infected with HSV will show characteristic changes, and these can be observed by obtaining a sample from the lesion and smearing it on a microscope slide (e.g. Tzanck smear). This test is not recommended due to low sensitivity (less than 80%) and lack of differentiation of HSV-1 from HSV-2.

- Blood test. This test analyzes a sample of your blood for the presence of HSV antibodies to detect a past herpes infection.

To confirm a diagnosis of genital herpes, your doctor will likely take a sample from an active sore. One or more tests of these samples are used to see if you have herpes simplex virus (HSV), infection and show whether the infection is HSV-1 or HSV-2.

Less often, a lab test of your blood may be used for confirming a diagnosis or ruling out other infections.

Your doctor will likely recommend that you get tested for other STDs. Your partner should also be tested for genital herpes and other STDs.

Genital herpes treatment

There’s no cure for genital herpes. Treatment with prescription antiviral medications may:

- Help sores heal sooner during an initial outbreak

- Lessen the severity and duration of symptoms in recurrent outbreaks

- Reduce the frequency of recurrence

- Minimize the chance of transmitting the herpes virus to another

Genital herpes anti-viral medications include 15, 19:

- Acyclovir (Zovirax) 400 mg orally 3 times/day for 7–10 days

- OR

- Valacyclovir (Valtrex) 1 gm orally 2 times/day for 7–10 days

- OR

- Famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times/day for 7–10 days

* Treatment can be extended if healing is incomplete after 10 days of therapy.

Despite some evidence from animal models that early treatment may impact the long-term natural history of the infection, human trials have shown that oral acyclovir treatment of primary genital herpes does not influence the frequency of subsequent genital recurrences 38, 39.

These antiviral drugs will stop the herpes simplex virus multiplying once it reaches the skin or mucous membranes but cannot eradicate the virus from its resting stage within the nerve cells. They can therefore shorten and prevent episodes while the drug is being taken, but a single course cannot prevent future episodes.

Your doctor may prescribe anti-viral medication to help reduce the severity of genital herpes symptoms. This is most effective when started within 72 hours of the first symptoms.

If you have frequent or severe recurrent episodes there are medications available to help control them.

Other treatments being studied include:

- Imiquimod cream, an immune enhancer

- Human leukocyte interferon alpha cream.

Both appear less beneficial than conventional antiviral drugs.

Your doctor may recommend that you take the medicine only when you have symptoms of an outbreak or that you take a certain medication daily, even when you have no signs of an outbreak. These medications are usually well-tolerated, with few side effects.

- Different formulations of topical antiviral creams are available. They are not generally recommended for genital herpes.

Cold sore

Cold sores also called fever blisters or herpes labialis, are caused by a contagious virus called herpes simplex virus (HSV). Cold sores are tiny, fluid-filled blisters on and around the border of your lips (Figure 6). Cold sores may also appear on other areas of your face, such as your chin or nose. These blisters are often grouped together in patches. After the blisters break, a crust forms over the resulting sore. Cold sores usually heal in two to four weeks without leaving a scar. There are two types of herpes simplex virus. Type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) usually causes oral herpes, or cold sores. Type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infects more than half of the U.S. population by the time they reach their 20s. Type 2 herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) usually affects the genital area. However, either HSV-1 or HSV-2 can affect almost any area of skin or mucous membrane.

Even though they are called cold sores, they have nothing to do with having a cold. You catch a cold sore by coming into close contact with someone who has a cold sore, such as by kissing. Also, not everyone who comes into contact with the virus will get a cold sore. For these people, the virus just never becomes active. But the majority of people who are exposed to a cold sore will have some sort of reaction. It may be that they get one cold sore and never have another. Or they may have cold sore outbreaks several times a year.

After the primary episode of infection, the herpes simplex virus (HSV) resides in a latent state in spinal dorsal root nerves that supply sensation to your skin. During a recurrence, the virus follows the nerves onto the skin or mucous membranes, where it multiplies, causing the clinical lesion. After each attack and lifelong, it enters the resting state.

During an attack, the herpes simplex virus (HSV) can be inoculated into new sites of skin, which can then develop blisters as well as the original site of infection.

Some people have no symptoms from the infection. But others develop painful and unsightly cold sores. Cold sores usually occur outside the mouth, on or around the lips. When they are inside the mouth, they are usually on the gums or the roof of the mouth. They are not the same as canker sores, which are not contagious.

Because cold sores are caused by a virus there is no cure for cold sores. They normally go away on their own in a few weeks. Antiviral medicines can help them heal faster. They can also help to prevent cold sores in people who often get them. Other medicines can help with the pain and discomfort of the sores. These include ointments that numb the blisters, soften the crusts of the sores, or dry them out. Protecting your lips from the sun with sunblock lip balm can also help.

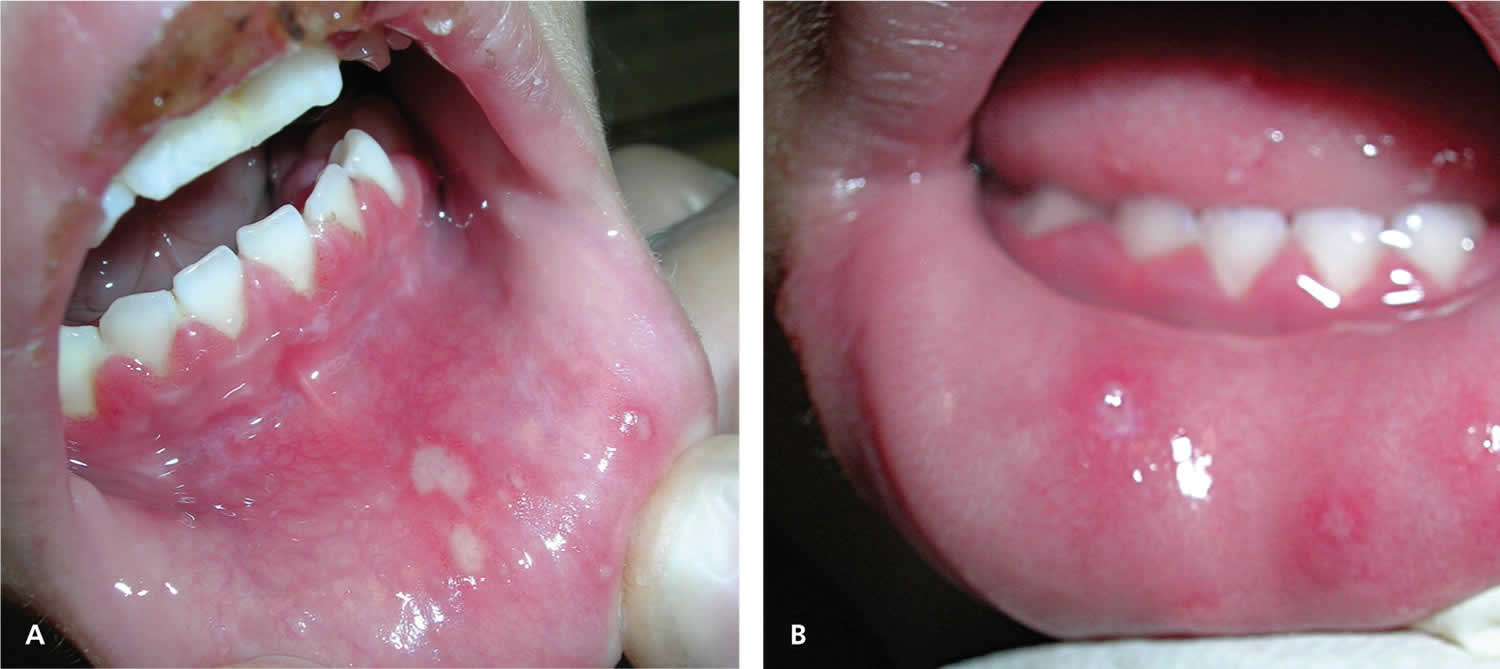

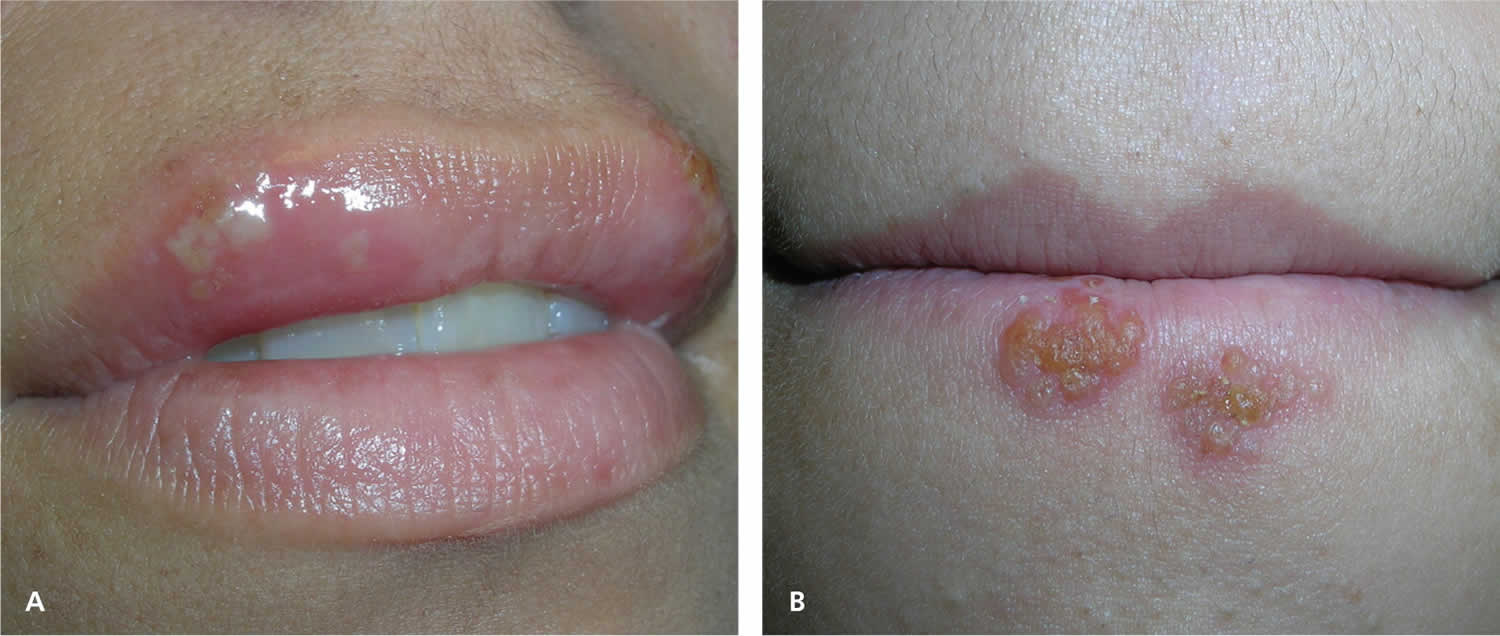

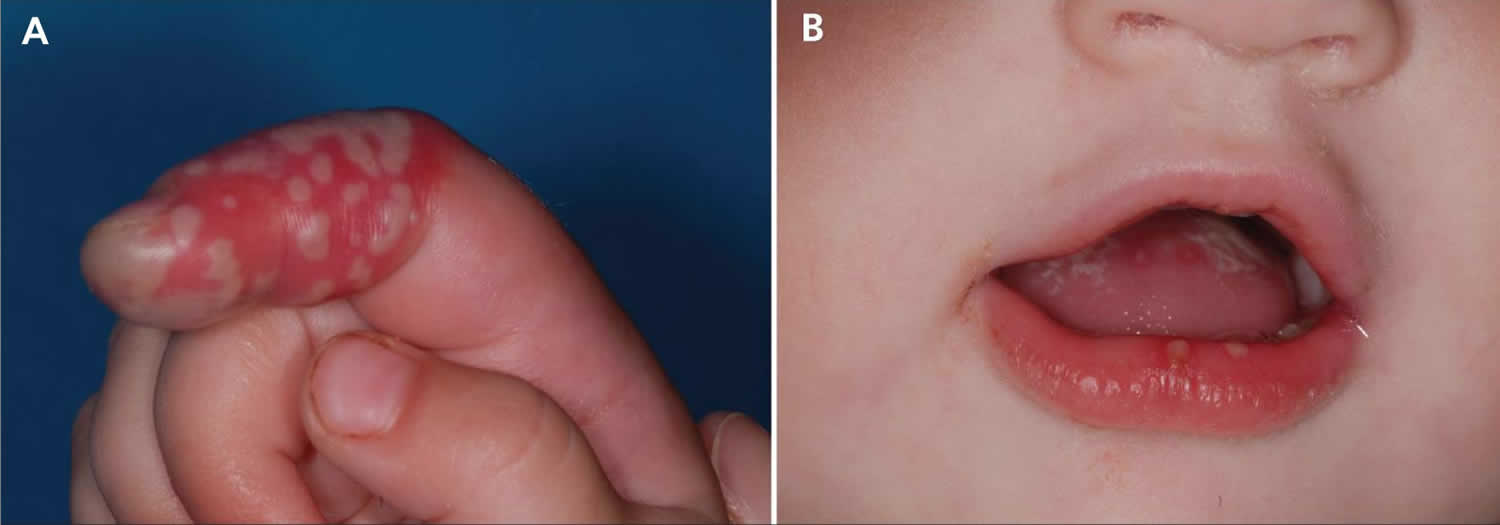

Figure 6. Primary oral herpes (primary herpetic gingivostomatitis) caused by herpes simplex virus type 1

Footnote: (A) a four-year-old girl with lower lip ulcers and crusting on the upper lip, and (B) a two-year-old girl with ulcers on the lower lip and tongue. Both patients show visible gingivitis with reddened, inflamed, and swollen gums.

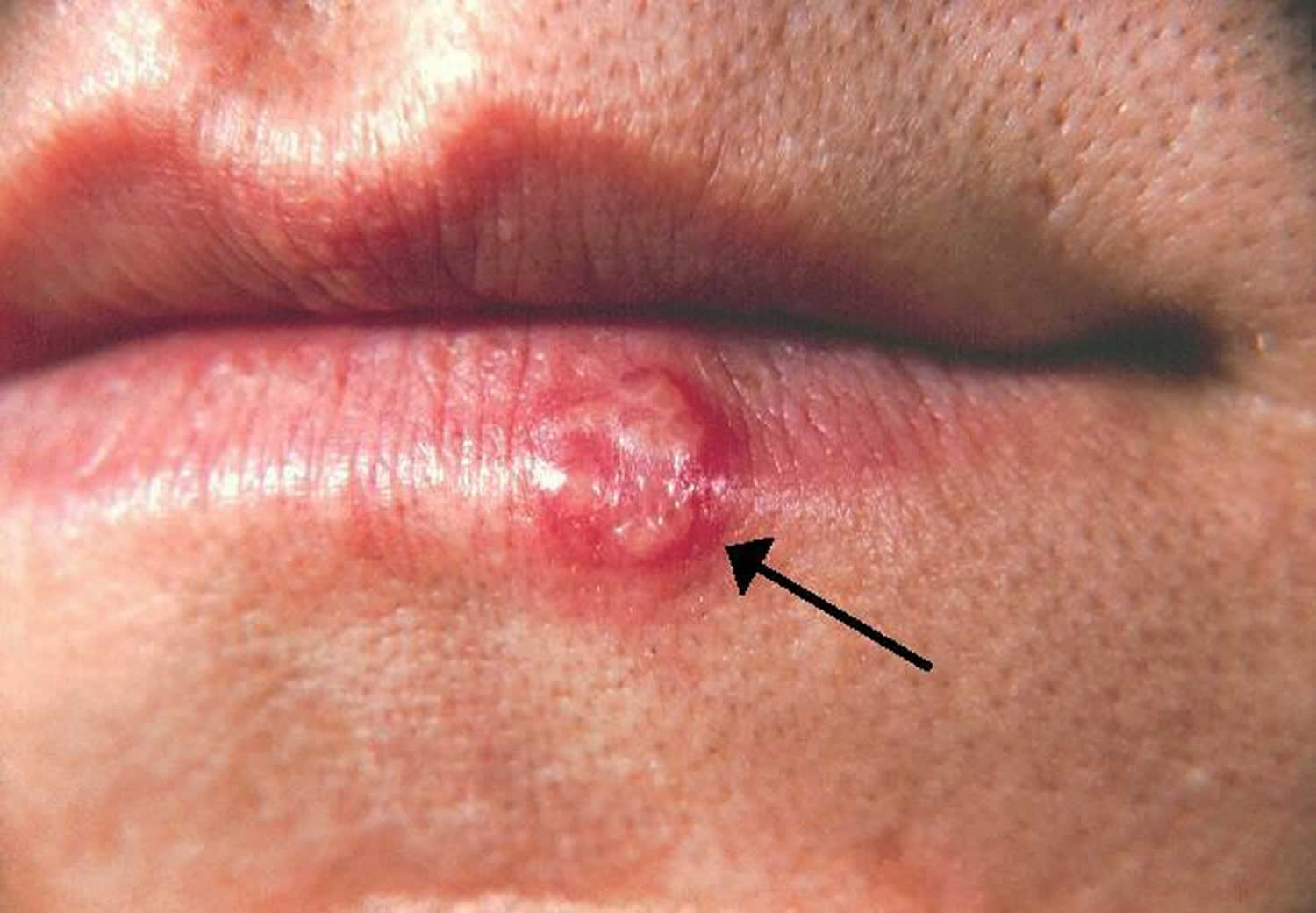

[Source 40 ]Figure 7. Cold sore on lip

Figure 8. Recurrent herpes simplex virus

Footnote: Young girl with recurrent herpes simplex virus type 1 showing vesicles on a red base at the vermilion border.

[Source 40 ]Figure 9. Recurrent oral herpes

Footnote: (A) Ulcers that form after the vesicles break, as shown in an adult women with herpes labialis. (B) Recurrent herpes simplex virus type 1 in the crusting stage seen at the vermilion border.

[Source 40 ]Figure 10. Oral herpes tongue in a patient with weak immune system causing a severe and large ulcer on tongue

Figure 11. Facial herpes

Cold sores generally clear up without treatment. See your doctor if you have more severe symptoms or a weakened immune system (e.g., you have HIV, on immune suppressant medications or you are having cancer treatment):

- You have a weakened immune system

- The cold sores don’t heal within two weeks

- Symptoms are severe

- You have frequent recurrences of cold sores

- You experience irritation in your eyes

It’s also a good idea to see your doctor if:

- there are signs the cold sore is infected, such as redness around the sore, pus and a fever

- you aren’t sure you have a cold sore

- the cold sore isn’t healing, it’s spreading or you have more than one cold sore

- your cold sore has spread to near your eyes

- you get cold sores often

Antibiotics may be needed if the cold sore gets infected.

Does having cold sore mean I have a sexually transmitted infection?

Having a cold sore does not mean that you have a sexually transmitted infection (STI). Most cold sores are caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Genital herpes (a type of STD) is typically caused by HSV-2. However, it is possible to transmit HSV-1 from a cold sore to the genital area during oral sex. In short, it is possible to get genital herpes from a cold sore from oral sex.

Are cold sores herpes?

Yes. Cold sores are caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV). There are two types of herpes simplex virus. Type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) usually causes oral herpes, or cold sores. Type 1 herpes virus infects more than half of the U.S. population by the time they reach their 20s. Type 2 herpes simplex virus (HSV-2) usually affects the genital area.

Are cold sores contagious?

Yes. Cold sores are contagious even if you don’t see the sores. Cold sores are spread from person to person by close contact, such as kissing. Cold sores are caused by a herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) closely related to the one that causes genital herpes (HSV-2). Both of these viruses can affect your mouth or genitals and can be spread by oral sex.

Can you get genital herpes from a cold sore?

Yes, it is possible to get genital herpes from oral sex.

Genital herpes is caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). There are two types of herpes viruses — HSV-1 and HSV-2. Genital herpes is usually caused by HSV-2; oral herpes (cold sores) is usually caused by HSV-1.

However, genital herpes can also be caused by HSV-1. Someone with HSV-1 can transmit the virus through oral contact with another person’s genitals, anus, or mouth, even if they don’t have sores that are visible at the time.

Other than abstinence (not having sex) the best way to help prevent herpes is to use a condom during any type of sex (oral, vaginal, or anal). Girls should have their partners use a dental dam every time they receive oral sex to help protect against genital herpes. And if either partner has a sore, it’s best to not have sex until the sore has cleared up.

How long do cold sores last?