What is hibiscus tea good for

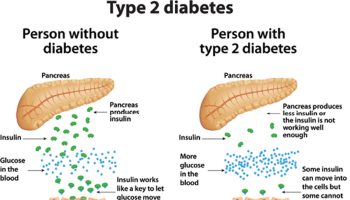

Hibiscus tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tisane) is a herbal tea made as an infusion from crimson or deep magenta-colored Hibiscus sabdariffa calyces (see Figure 1) (sepals) of the roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) flower. Hibiscus tea is consumed both hot and cold. Hibiscus tea is one of the most common ingredients found in commercial herbal tea (tisane) blends sold in the US 1. In other parts of the world, Hibiscus sabdariffa calyces (see Figures 1 and 2) and beverages derived from them, are called hibiscus tea, bissap, roselle, red sorrel, agua de Jamaica, Lo-Shen, Sudan tea, sour tea, or karkade. Hibiscus sabdariffa decoctions and infusions of calyxes (hibiscus tea), and on occasion Hibiscus leaves, are used in at least 10 countries worldwide in the treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia with no reported adverse events or side effects. In test tube studies show that Hibiscus sabdariffa has antioxidant properties 2, 3 and, in animal models, extracts of Hibiscus sabdariffa flower have demonstrated hypocholesterolemic 4 and antihypertensive properties 5. Concentrated Hibiscus sabdariffa beverages lower blood pressure (BP) 7 in patients with hypertension 6 and type 2 diabetes 7 compared with black tea (Camelia sinensis) and have an effect similar to common hypotensive drugs 8.

Table 1. Hibiscus sabdariffa raw (Roselle) nutrition facts

| Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g | |||||

| Approximates | |||||||

| Water | g | 86.58 | |||||

| Energy | kcal | 49 | |||||

| Energy | kJ | 205 | |||||

| Protein | g | 0.96 | |||||

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0.64 | |||||

| Ash | g | 0.51 | |||||

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 11.31 | |||||

| Minerals | |||||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 215 | |||||

| Iron, Fe | mg | 1.48 | |||||

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 51 | |||||

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 37 | |||||

| Potassium, K | mg | 208 | |||||

| Sodium, Na | mg | 6 | |||||

| Vitamins | |||||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 12 | |||||

| Thiamin | mg | 0.011 | |||||

| Riboflavin | mg | 0.028 | |||||

| Niacin | mg | 0.31 | |||||

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 14 | |||||

| Retinol | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 287 | |||||

| Lipids | |||||||

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0 | |||||

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | |||||

Table 2. Hibiscus tea brewed nutrition facts

| Nutrient | Unit | Value per 100 g | |||||

| Approximates | |||||||

| Water | g | 99.58 | |||||

| Energy | kcal | 0 | |||||

| Energy | kJ | 0 | |||||

| Protein | g | 0 | |||||

| Total lipid (fat) | g | 0 | |||||

| Ash | g | 0.42 | |||||

| Carbohydrate, by difference | g | 0 | |||||

| Fiber, total dietary | g | 0 | |||||

| Sugars, total | g | 0 | |||||

| Sucrose | g | 0 | |||||

| Glucose (dextrose) | g | 0 | |||||

| Fructose | g | 0 | |||||

| Lactose | g | 0 | |||||

| Maltose | g | 0 | |||||

| Galactose | g | 0 | |||||

| Minerals | |||||||

| Calcium, Ca | mg | 8 | |||||

| Iron, Fe | mg | 0.08 | |||||

| Magnesium, Mg | mg | 3 | |||||

| Phosphorus, P | mg | 1 | |||||

| Potassium, K | mg | 20 | |||||

| Sodium, Na | mg | 4 | |||||

| Zinc, Zn | mg | 0.04 | |||||

| Copper, Cu | mg | 0 | |||||

| Manganese, Mn | mg | 0.477 | |||||

| Selenium, Se | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamins | |||||||

| Vitamin C, total ascorbic acid | mg | 0 | |||||

| Thiamin | mg | 0 | |||||

| Riboflavin | mg | 0 | |||||

| Niacin | mg | 0.04 | |||||

| Pantothenic acid | mg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 0 | |||||

| Folate, total | µg | 1 | |||||

| Folic acid | µg | 0 | |||||

| Folate, food | µg | 1 | |||||

| Folate, DFE | µg | 1 | |||||

| Choline, total | mg | 0.4 | |||||

| Vitamin B-12 | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin B-12, added | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin A, RAE | µg | 0 | |||||

| Retinol | µg | 0 | |||||

| Carotene, beta | µg | 0 | |||||

| Carotene, alpha | µg | 0 | |||||

| Cryptoxanthin, beta | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin A, IU | IU | 0 | |||||

| Lycopene | µg | 0 | |||||

| Lutein + zeaxanthin | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) | mg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin E, added | mg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin D (D2 + D3) | µg | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin D | IU | 0 | |||||

| Vitamin K (phylloquinone) | µg | 0 | |||||

| Lipids | |||||||

| Fatty acids, total saturated | g | 0 | |||||

| 04:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 06:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 08:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 10:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 12:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 14:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 16:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 18:00:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| Fatty acids, total monounsaturated | g | 0 | |||||

| 16:1 undifferentiated | g | 0 | |||||

| 18:1 undifferentiated | g | 0 | |||||

| 20:01:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 22:1 undifferentiated | g | 0 | |||||

| Fatty acids, total polyunsaturated | g | 0 | |||||

| 18:2 undifferentiated | g | 0 | |||||

| 18:3 undifferentiated | g | 0 | |||||

| 18:04:00 | g | 0 | |||||

| 20:4 undifferentiated | g | 0 | |||||

| 20:5 n-3 (EPA) | g | 0 | |||||

| 22:5 n-3 (DPA) | g | 0 | |||||

| 22:6 n-3 (DHA) | g | 0 | |||||

| Fatty acids, total trans | g | 0 | |||||

| Cholesterol | mg | 0 | |||||

| Other | |||||||

| Alcohol, ethyl | g | 0 | |||||

| Caffeine | mg | 0 | |||||

| Theobromine | mg | 0 | |||||

Figure 1. Hibiscus sabdariffa calyces

Figure 2. Dried hibiscus calyces

Figure 3. Hibiscus tea

Health benefits of hibiscus tea

Health benefits of hibiscus tea

Hibiscus sabdariffa (hibiscus tea) is consumed as a beverage in the United States 1, Mexico 10, Nigeria and other West African countries 11, 12, Egypt 13, Iran 14, India 15, Thailand 16 and Tawian 17, among other countries. Ethnomedicinal studies have reported the use of Hibiscus sabdariffa for the treatment of various cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension in Egypt, Jordan, and Trinidad and Tobago 18, 19, hypotension in Jordan and Iraq 20, hyperlipidemia in Jordan, Greece, Brazil, and Trinidad and Tobago 19, 21, and obesity in Iraq, Greece, and Brazil 21, 22.

The flowers (Figure 3), or more specifically the Hibiscus sabdariffa calyxes (Figure 1), are typically prepared using an aqueous decoction or infusion 18. However, the Bedouins in the North Badia region of Jordan use the Hibiscus sabdariffa leaves, as well as the flowers, and they drink the infusions hot when treating high blood pressure and cold when treating low blood pressure 23. In Trinidad and Tobago only the Hibiscus sabdariffa leaves are used to treat high blood pressure and the flower and seeds are used to treat high cholesterol 24. Dosing was only described in 1 of the 7 ethnobotancial studies reviewed 22. Mati and colleagues 22 discovered that herbalists in the Kurdistan Autonomous Region of Iraq recommend drinking 1 cup/day of an infusion of 1 tsp (1/2 tsp when ground) of Hibiscus sabdariffa flowers in 1 cup warm water for the treatment of hypotension and 2 cups/day of a decoction of 2 tsp of the Hibiscus sabdariffa flowers in 1/2 L of water or 1 cup/day of a decoction of 50 g in 2 cups of water for the treatment of obesity.

Ethnomedicinal studies provide evidence for the widespread use of a tea made with Hibiscus sabdariffa calyxes to treat hypertension and hyperlipidemia, but these studies provide little guidance for animal and human studies through their lack of attention to cultivation, preparation, and consumption patterns. Animal studies have consistently shown that consumption of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract reduces blood pressure in a dose dependent manner. They have also shown that total cholesterol, LDL “bad” cholesterol, and triglycerides were lowered in the majority of normolipidemic, hyperlipidemic, and diabetic animal models, whereas HDL “good” cholesterol was generally not affected by the consumption of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract.

Hibiscus tea blood pressure

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial 1 involving 65 prehypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults, age 30–70 years, not taking blood pressure (BP)-lowering medications, with either 3 X 240-mL servings/day of brewed hibiscus tea or placebo beverage for 6 week. The study found that daily consumption of 3 servings of Hibiscus sabdariffa (hibiscus) tea, an amount readily incorporated into the diet, effectively lowered blood pressure in pre-hypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults 1. The maximum hypotensive effect was observed after a few weeks of 3 servings of Hibiscus sabdariffa (hibiscus) tea. However, further research is warranted to understand the relative contributions of the acute and chronic actions of hibiscus tea.

The blood pressure-lowering effects of hibiscus tea observed in that study 1 were greater than those reported in 2 large dietary interventions, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) 25 and PREMIER 26 trials, both of which included participants with baseline blood pressure measures similar to this study volunteers. After 8 wk of consuming a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, the difference in systolic blood pressure between the placebo and treatment groups in the DASH study was 2.8 mm Hg, whereas after consuming the combination diet rich in fruits and vegetables plus low-fat dairy products, this difference was 5.5 mm Hg. After 6 months, participants in the PREMIER study given established lifestyle advice (i.e. lose weight, increase physical activity, and reduce sodium and alcohol consumption) lowered their systolic blood pressure by 3.7 mm Hg greater than those given more general advice (control group), whereas participants who were given the established advice and followed the DASH diet lowered their systolic blood pressure by 4.3 mm Hg compared with the control group. In a study, the difference in systolic blood pressure between the placebo and hibiscus tea groups was 5.9 mm Hg, similar to the systolic blood pressure-lowering effect obtained by following the combination DASH diet for 8 weeks. Effects of this magnitude are considered important for public health 1. On a population basis, a 5-mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure would result in a 14% overall reduction in mortality due to stroke, a 9% reduction in mortality due to coronary heart disease, and a 7% reduction in all-cause mortality 27. Although the health benefits of following the dietary pattern described in the DASH and PREMIER trials are substantiated, consumers may find these dietary changes too complex or difficult to comply with in full. In contrast, adding hibiscus tea to each meal is simple and, as such, may be an effective strategy for controlling blood pressure among pre-hypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults. Future research should consider whether combining the DASH diet with daily hibiscus tea consumption confers a greater reduction in blood pressure than either approach alone.

Table 3. Hypertension and Hibiscus sabdariffa randomized clinical trials and effects on systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure

| Primary author, year | Condition | Sample size | Substance | Plant part | Extract mode | Dose | # of doses per day | Days dose taken | Mean change in SBP (SD) | Within group p-value | Mean change in DBP (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McKay, 2010 1 | Hypertension | 31(30) | AHFC | W | 1.2/240a | 3 | 42 | 1.3 (10.0) | NS | 0.5 (7.5) | |

| McKay, 2010 1 | Hypertension | 35(35) | HS | C | W | 2.25/240b | 3 | 42 | 7.2 (11.4) | Red | 3.1 (7.0) |

| Haji, 1999 28 | Hypertension | 40(23) | BT | L | W | 2/1c | 1 | 12 | 6.3 (7.7) | Red | 3.5 (6.0) |

| Haji, 1999 28 | Hypertension | 40(31) | HS | N/A | W | 2/1c | 1 | 12 | 17.6 (6.8) | Red | 10.9 (5.4) |

| Mozaffari-Khosravi, 2009 29 | Hypertension, Diabetes | 30(26) | BT | L | W | 2/240b | 2 | 30 | 8.4 (11.0) | Inc | 4.6 (11.8) |

| Mozaffari-Khosravi, 2009 29 | Hypertension, Diabetes | 30(27) | HS | C | W | 2/240b | 2 | 30 | 15.4 (7.5) | Red | 4.3 (12.3) |

| Herrera-Arellano, 2004 30 | Hypertension | 37(32) | Meda | 25d | 2 | 28 | 16.4 (9.6) | Red | 13.1 (7.2) | ||

| Herrera-Arellano, 2004 30 | Hypertension | 53(38) | HS | C | W | 9.62e | 1 | 28 | 14.2 (11.8) | Red | 11.2 (6.9) |

| Herrera-Arellano, 2007 31 | Hypertension | 93(N/A) | Medb | 10d | 1 | 28 | 23.3 (7.0) | Red | 15.4 (6.0) | ||

| Herrera-Arellano, 2007 31 | Hypertension | 100(N/A) | HS | C | W | 250e | 1 | 28 | 17.1 (10.0) | Red | 12.0 (7.0) |

Notes:

Condition: Hyper=hypertension, Diab=diabetes; Sample size= beginning of study (end of study), N/A=not available;

Substance: HS=Hibiscus sabdariffa, AHFC=artificial hibiscus flavor concentrate, BT=Black tea, Med=blood pressure medication,

Dose: a=mL substance/mL extraction substance;

Dep=depressed, a=more than comparator,

The potential mechanisms of action for the blood pressure-lowering effect of hibiscus tea were shown in laboratory test tube and animal studies that show that Hibiscus sabdariffa is a blood vessels relaxant 33, perhaps via action on calcium channels 34, an Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitor is medicine used in the treatment of hypertension and congestive heart failure) 35, and a diuretic 36. The angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor activity and natriuretic effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa have also been observed in human studies 8. Other potential mechanisms of action related to the effects of the anthocyanins present in Hibiscus sabdariffa are also possible 37.

Table 4. Major phenolic components and antioxidant activity per serving of Hibiscus sabdariffa tea

| Component | Hibiscus tea |

| unit/240 mL | |

| Total phenols, mg gallic acid equivalents | 21.85 |

| Total anthocyanins, mg CGE | 7.04 |

| Delphinidin-3-sambubioside, mg CGE | 3.69 |

| Cyanidin-3-sambubioside, mg CGE | 0.02 |

| ORAC, μmol trolox equivalents | 1950 |

Note: CGE = Cyanidin glucoside equivalents; Antioxidant capacity analyzed using the ORAC assay

[Source 38]The observed hypertensive-lowering effect of hibiscus tea could be due to its major flavonoid components, delphinidin-3-sambubioside and cyanidin-3-sambubioside. However, other phytochemicals present might also contribute to this effect 39. Herraro-Arellano et al. 8 demonstrated the blood pressure-lowering effects of a standardized Hibiscus sabdariffa extract containing 250 mg of these anthocyanins in a 4-week study of 171 hypertensive patients. The Hibiscus sabdariffa extract lowered blood pressure from baseline after 4 week, although the magnitude of this effect was lower than that achieved in the comparison group treated with 10 mg lisinopril (a medicine used to lower blood pressure). Other bioavailability studies show that anthocyanins are rapidly absorbed and eliminated and that they are absorbed with poor efficiency 40.

Previous studies conducted in hypertensive patients used a higher dose of Hibiscus sabdariffa to compare its effects with that of either black tea 6 or a hypotensive drug 41. Haji Faraji and Haji Tarkhani 6 tested 54 patients, mean age 52 years, in a hospital-based, randomized, clinical trial over a 15-days period. In their study, the treatment group consumed 1 glass daily of Hibiscus sabdariffa tea prepared with 2 spoonfuls of blended tea per glass brewed in boiling water for 20–30 min. No quantitative analysis of the potential active ingredients in the Hibiscus sabdariffa beverage was reported, although it can be assumed that the higher quantity of dried Hibiscus sabdariffa calyces used in their study, and the longer brew time. Their control group consumed black tea prepared similarly. Black tea is not an inert placebo because it contains caffeine, catechins, and flavonols, compounds known to affect vasodilation. Herrera-Arellano et al. 41 compared Hibiscus sabdariffa with an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor in a randomized trial of 75 patients aged 30–80 years. In their study, an infusion prepared with 10 g of dry Hibiscus sabdariffa calyces in 0.5 L water (9.6 mg anthocyanins) and administered daily was compared with 25 mg captopril administered twice daily for 4 week and systolic blood pressure did not differ between the groups. The magnitude of change in systolic blood pressure from baseline in both the Haji Faraji and Haji Tarkhani 6 and Herrera-Arellano et al. 41 studies was approximately double the amount observed. This outcome was not unexpected, because the participants in these nonplacebo–controlled studies had higher initial systolic blood pressure (+10–30 mm Hg) and diastolic blood pressure (+12–22 mm Hg) and were taking antihypertensive medication prior to the intervention.

Wahabi et al in a more recent 2015 systematic review on the effectiveness of Hibiscus sabdariffa in the treatment of hypertension 42 found no reliable evidence to recommend Hibiscus sabdariffa as a treatment for primary hypertension in adults. The four randomized controlled studies identified in this review 42 with a total of 390 patients, two studies compared Hibiscus sabdariffa to black tea; one study compared it to captopril and one to lisinopril. The studies found that Hibiscus had greater blood pressure reduction than tea but less than the ACE-inhibitors. However, all studies, except one, were short term and of poor quality with a Jadad scoring of <3 and did not meet international standards. Based on available conflicting evidence, more studies are needed before Hibiscus sabdariffa can reliably be recommended for the treatment of primary hypertension in adults.

Hibiscus sabdariffa and high cholesterol

The clinical study populations were diverse and included healthy people as well as those with metabolic syndrome 43, hyperlipidemia 44, hypertension 45, or type 2 diabetes 29 (Table 5). The study designs compared different doses of Hibiscus sabdariffa 46 or compared Hibiscus sabdariffa to black tea 29, diet and a combination of Hibiscus sabdariffa and diet 43 or a placebo 47. In two studies the dried calyxes of Hibiscus sabdariffa were prepared and administered as a tea 29, 48 and in the other studies fresh calyxes 46, 10 or leaves 15 were prepared as a standardized powdered extract and administered in capsules. The doses of Hibiscus sabdariffa per serving and the frequency of administration varied from .015 g of dried calyxes prepared in water and administered twice daily 48 to 450 g of dried calyxes prepared in water and administered up to 3 times a day 46. Alcohol extractions formulated with 500 g of fresh calyxes were administered once daily 43 and alcohol extracts made from 60,000 g of fresh leaves were administered twice daily 15. The duration of the studies ranged from 15 days 45 to 90 days 15 with most lasting one month.

The effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa on total cholesterol varied. One brief 15 day study reported a significant increase in total cholesterol among hypertensive patients administered Hibiscus sabdariffa 45. In this same study, HDL “good” cholesterol increased and triglyceride and LDL “bad” cholesterol values remained unchanged. Of the remaining 4 studies, one showed no significant change in total cholesterol and the month long studies showed significant decreases in total cholesterol among participants with hypertension, metabolic syndrome and those receiving the two lower doses of Hibiscus sabdariffa 29, 43, 46. Hibiscus sabdariffa significantly increased beneficial HDL “good” cholesterol levels in participants with and without metabolic syndrome 43 and hypertension 29. LDL “bad” cholesterol was significantly decreased as a result of the consumption of Hibiscus sabdariffa in participants with metabolic syndrome 43, hyperlipidemia 15 and type 2 diabetes 29. Triglyceride levels were significantly decreased by Hibiscus sabdariffa in participants with hyperlipidemia 15, type 2 diabetes 29, and without metabolic syndrome 43.

Most studies did not make clear the type of randomized clinical trial being conducted and in many cases there were study design problems. In several randomized clinical trials black tea was used as the comparator, as opposed to a placebo, making the results difficult to interpret because of the active pharmacological properties of black tea. McKay and colleagues’ 1 in the only placebo-controlled trial to date provided a notable exception to this trend by using a placebo drink that was non-active and is used in the beverage industry to mimic the flavor of Hibiscus sabdariffa tea in commercially prepared drinks. In some comparative effectiveness trials it was difficult to compare effectiveness between treatments because the medication was not administered as directed by doctors 49, whereas other trials provided realistic comparators. The results from the study on dose response are difficult to interpret because the baseline values for total cholesterol differed substantially between groups 46.

Additionally, there were several problems specific to the cholesterol randomized clinical trials. Differences between groups were impossible to assess because none of the studies included effect sizes or statistical analyses of the between-group differences. Another problem with most of the cholesterol trials was short study duration with 4 trials lasting 15 days to 30 days and only one trial of a longer 90 day duration. In general, lipid profiles can take up to 2 months to reflect meaningful change in patients given statin medication or modifications to their diet and lifestyle 50. The hypertension trials selected patient populations with mild to moderate hypertension with only one study providing the additional condition of diabetes, whereas the patient populations in the cholesterol trials had an array of conditions, many of which did not include elevated cholesterol, making it difficult to assess the effectiveness of Hibiscus sabdariffa in treating hyperlipidemia.

There were also several problems with the preparation of Hibiscus sabdariffa. Many of the studies did not report the part of the plant that was used in the preparation. Kuriyan and colleagues 51 used the leaves in their extract without explanation, whereas the calyxes are most commonly used in Hibiscus sabdariffa preparations. In addition, the amount of Hibiscus sabdariffa used in preparations and the dose administered varied greatly with Mohagheghi and colleagues 52 choosing to use an extremely small amount of Hibiscus sabdariffa calyxes in the preparation per dose and many of the studies failing to include any measure of marker constituents. The absence of information related to product content and the method of preparation and the lack of uniformity of extracts made it difficult to compare findings between studies. In addition, the lack of information regarding ethnobotanical use made it difficult to determine the relationship between the studies and traditional therapeutic use.

Table 5. Cholesterol and Hibiscus sabdariffa randomized clinical trials and effects on total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglycerides

| Primary author, year | Condition | Sample size | Substance | Plant part | Extract mode | Dose | # of doses per day | Days dose taken | TC (SD) | HDL-C (SD) | LDL-C (SD) | TG (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 206 (39) | 44.3 (8.3) | 130.8 (29) | 153.5 (59) | ||||||||

| Mohagheghi, 2011 45 | Hyperten | 45 (42) | HS | C | W | .015/2a | 2 | 15 | 212 (37) | 46 (7.2) | 133.2 (26) | 157.5 (58) |

| 0 | 202.6 (41.6) | 41.6 (10.3) | 124.1 (41.7) | 148.0 (61.3) | ||||||||

| Gurrola-Diaz, 2010 43 | None | 26 (26) | HS | C | A | 100b | 1 | 30 | 197.5 (37.0) | 45.8 (9.3) | 124.5 (35.5) | 113.8 (54.1) |

| 0 | 199.8 (40.5) | 32.0 (5.8) | 130.1 (34.8) | 172.3 (107.4) | ||||||||

| Gurrola-Diaz, 2010 43 | MeSy | 18 (18) | HS | C | A | 100b | 1 | 30 | 179.7 (21.2) | 44.5 (8.3) | 104.1 (20.4) | 137.6 (62.1) |

| 0 | 207.1 (32.5) | 42.0 (9.4) | 155.3 (13.9) | 159.9 (90.6) | ||||||||

| Kuriyan, 2010 15 | Hyperlip | 30 (28) | HS | L | A | 500b | 2 | 90 | 198.5 (33.2) | 42.6 (8.9) | 127.6 (24.1) | 143.3 (73.9) |

| 0 | 236.2 (58.1) | 48.2 (10.6) | 137.5 (53.4) | 246.1 (84.9) | ||||||||

| Mozaffari-Khosravi, 2009 29 | Diab | 30 (27) | HS | C | W | 2/240c | 2 | 30 | 218.6 (38.4) | 56.1 (11.3) | 128.5 (41.2) | 209.2 (57.2) |

| Lin, 2007 53 | Hyperlip | 14 (N/A) | HS | F | W | 500b | 3 | 0 | 201.9 (27.2) | |||

| 28 | 194.6 (24.2) | |||||||||||

| 6 | 0 | 223.4 (36.8) | ||||||||||

| Lin, 2007 53 | Hyperlip | 14 (N/A) | HS | F | W | 500b | 28 | 213.9 (37.0) | ||||

| 9 | 0 | 207.5 (26.5) | ||||||||||

| Lin, 2007 53 | Hyperlip | 14 (N/A) | HS | F | W | 500b | 28 | 212.6 (40.0) |

Notes:

Condition: Hyperten=hypertension, MeSy=metabolic syndrome, Hyperlip=hyperlipidemia, Diab=diabetes; Sample size= beginning of study (end of study), N/A=not available; Substance: HS=Hibiscus sabdariffa; Plant part used in extract=F=flower, C=calyx, L=leaf; Extract mode: W=water, A=alcohol;

Dose: a=g substance/glass of extraction substance,

Hibiscus tea side effects

Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts have a low degree of toxicity with a LD50 (Lethal Dose 50% is the amount of the substance required (usually per body weight) to kill 50% of the test population) ranging from 2,000 to over 5,000 mg/kg/day 32. There is no evidence of hepatic or renal toxicity as the result of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract consumption, except for possible adverse hepatic effects at high doses 32.

Summary

Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts are generally considered to have a low degree of toxicity. Studies demonstrate that Hibiscus sabdariffa consumption does not adversely effect liver and kidney function at lower doses, but may be hepatotoxic at extremely high doses. In addition, electrolyte levels generally are not effected by ingesting Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts despite its diuretic effects.

The daily consumption of Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx extracts significantly lowered systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure in adults with prehypertension to moderate essential hypertension and type 2 diabetes 32. In addition, Hibiscus sabdariffa tea was as effective at lowering blood pressure as Captropril, but less effective than Lisinopril. McKay and colleagues 1 provide a notable exception with their high quality placebo-controlled trial. As the findings related to the effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa on blood pressure from lower quality studies are consistent with those of this high quality study, the totality of evidence suggests that Hibiscus sabdariffa consumption may have a public health benefit due to its anti-hypertensive effects. However, in a more recent 2015 systematic review on the effectiveness of Hibiscus sabdariffa in the treatment of hypertension 42 found no reliable evidence to recommend Hibiscus sabdariffa as a treatment for primary hypertension in adults. The four randomized controlled studies identified in this review 42 do not provide reliable evidence to support recommending Hibiscus sabdariffa for the treatment of primary hypertension in adults. Based on available conflicting evidence, more studies are needed before Hibiscus sabdariffa can reliably be recommended for the treatment of primary hypertension in adults.

Over half of the randomized clinical trials showed that daily consumption of Hibiscus sabdariffa tea or extracts had a favorable influence on lipid profiles including reduced total cholesterol, LDL “bad” cholesterol, triglycerides as well as increased HDL “good” cholesterol. Regrettably many of the randomized clinical trials were of low quality and did a poor job characterizing the Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts and utilized a form that is not widely consumed making it difficult to determine the amount of public health benefit related to Hibiscus sabdariffa tea consumption. In a 2013 systematic review and meta analysis on the effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa on blood cholesterol, Aziz et al. 54 found based available evidence from randomized clinical trials does not support the efficacy of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. in lowering serum lipids. Overall, Hibiscus sabdariffa L. did not produce any significant effect on any of the outcomes examined, when compared with placebo, black tea or diet. Further rigorously designed trials with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm the effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa on serum lipids.

Anthocyanins found in abundance in Hibiscus sabdariffa calyxes are generally considered the phytochemicals responsible for the antihypertensive and hypocholesterolemic effects, however evidence has also been provided for the role of polyphenols and hibiscus acid. A number of potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain the hypotensive and anticholesterol effects, but the most common explanation is the antioxidant effects of the anthocyanins inhibit LDL “bad” cholesterol oxidation which impedes atherosclerosis, an important cardiovascular risk factor. Research on active compounds in Hibiscus sabdariffa and the mechanisms of action are still fairly nascent making it difficult to justify carrying out randomized clinical trials using anything other than the whole plant parts used in general practice.

This body of evidence interpreted together suggests that Hibiscus sabdariffa may have potential to reduce risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease (e.g. hypertension) and merits further study.

References- Diane L. McKay, C-Y. Oliver Chen, Edward Saltzman, Jeffrey B. Blumberg; Hibiscus Sabdariffa L. Tea (Tisane) Lowers Blood Pressure in Prehypertensive and Mildly Hypertensive Adults, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 140, Issue 2, 1 February 2010, Pages 298–303, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.115097 https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/140/2/298/4600320

- Tseng TH, Kao ES, Chu CY, Chou FP, Lin Wu HW, Wang CJ Protective effects of dried flower extracts of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. against oxidative stress in rat primary hepatocytes. Food Chem Toxicol. 1997;35:1159–64.

- Tee P, Yusof S, Suhaila M Antioxidative properties of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in linoleic acid model system. Nutr Food Sci. 2002;32:17–20.

- Chen CC, Hsu JD, Wang SF, Chiang HC, Yang MY, Kao ES, Ho YC, Wang CJ Hibiscus sabdariffa extract inhibits the development of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:5472–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12926900

- Odigie IP, Ettarh RR, Adigun SA Chronic administration of aqueous extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa attenuates hypertension and reverses cardiac hypertrophy in 2K–1C hypertensive rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86:181–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12738084

- Haji Faraji M, Haji Tarkhani A The effect of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on essential hypertension. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;65:231–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10404421

- Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Jalali-Khanabadi BA, Afkhami-Ardekani M, Fatehi F, Noori-Shadkam M The effects of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on hypertension in patients with type II diabetes. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:48–54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18685605

- Herrera-Arellano A, Miranda-Sanchez J, Avila-Castro P, Herrera-Alvarez S, Jiménez-Ferrer JE, Zamilpa A, Román-Ramos R, Ponce-Monter H, Tortoriello J Clinical effects produced by a standardized herbal medicinal product of Hibiscus sabdariffa on patients with hypertension. A randomized, double-blind, lisinopril-controlled clinical trial. Planta Med. 2007;73:6–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17315307

- United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy Release. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/search/list

- Gurrola-Diaz CM, Garcia-Lopez PM, Sanchez-Enriquez S, Troyo-Sanroman R, Andrade-Gonzalez I, Gomez-Leyva JF. Effects ofHibiscus sabdariffa extract powder and preventive treatment (diet) on the lipid profiles of patients with metabolic syndrome (MeSy) Phytomedicine. 2010;17:500–505. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19962289

- Farombi EO, Ige OO. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of ethanolic extract from dried calyx ofHibiscus sabdariffa in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007;21:601–609. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18034661

- Mojiminiyi FBO, Dikko M, Muhammad BY, Ojobor PD, Ajagbonna OP, Okolo RU, Igbokwe UV, Mojiminiyi UE, Fagbemi MA, Bello SO, Anga TJ. Antihypertensive effect of an aqueous extract of the calyx ofHibiscus sabdariffa. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:292–297 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17482378

- El-Saadany SS, Sitohy MZ, Labib SM, El-Massry RA. Biochemical dynamics and hypocholesterolemic action ofHibiscus sabdariffa(Karkade) Food / Nahrung. 1991;35:567–576. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1787844

- Mohagheghi A, Maghsoud S, Khashayar P, Ghazi-Khansari M. The effect ofHibiscus sabdariffa on lipid profile, creatinine, and serum electrolytes: A randomized clinical trial. ISRN Gastroenterology. 2011;2011:4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3168576

- Kuriyan R, Kumar D, R R, Kurpad A. An evaluation of the hypolipidemic effect of an extract ofHibiscus sabdariffa leaves in hyperlipidemic Indians: a double blind, placebo controlled trial, BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010;10:27 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2906418/

- Hirunpanich V, Utaipat A, Morales NP, Bunyapraphatsara N, Sato H, Herunsale A, Suthisisang C. Hypocholesterolemic and antioxidant effects of aqueous extracts from the dried calyx ofHibiscus sabdariffa L. in hypercholesterolemic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:252–260 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16213683

- Peng C-H, Chyau C-C, Chan K-C, Chan T-H, Wang C-J, Huang C-N. Hibiscus sabdariffa polyphenolic extract inhibits hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and glycation-oxidative stress while improving insulin resistance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:9901–9909 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21870884

- AbouZid SF, Mohamed AA. Survey on medicinal plants and spices used in Beni-Sueif, Upper Egypt. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011;7:18 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141364/

- Lans C. Ethnomedicines used in Trinidad and Tobago for reproductive problems. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007;3:13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1838898/

- Alzweiri M, Sarhan AA, Mansi K, Hudaib M, Aburjai T. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Jordan, the Northern Badia region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:27–35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21335083

- Hanlidou E, Karousou R, Kleftoyanni V, Kokkini S. The herbal market of Thessaloniki (N Greece) and its relation to the ethnobotanical tradition. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91:281–299. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15120452

- Mati E, de Boer H. Ethnobotany and trade of medicinal plants in the Qaysari Market, Kurdish Autonomous Region, Iraq. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:490–510 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20965241

- Alzweiri M, Sarhan AA, Mansi K, Hudaib M, Aburjai T. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Jordan, the Northern Badia region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:27–35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21335083

- Lans C. Ethnomedicines used in Trinidad and Tobago for reproductive problems. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007;3:13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1838898/

- Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Vogt TM, Cutler JA, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–24. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM199704173361601

- Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ, Vollmer WM, Lin PH, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–93. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1357324

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JLJr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/42/6/1206.long

- Haji Faraji M, Haji Tarkhani AH. The effect of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on essential hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999;65:231–236 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10404421

- Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Jalali-Khanabadi BA, Afkhami-Ardekani M, Fatehi F. Effects of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on lipid profile and lipoproteins in patients with type II diabetes. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009;15:899–903 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19678781

- Herrera-Arellano A, Flores-Romero S, Chávez-Soto MA, Tortoriello J. Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract fromHibiscus sabdariffa in patients with mild to moderate hypertension: a controlled and randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:375–382 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15330492

- Herrera-Arellano A, Miranda-Sanchez J, Avila-Castro P, Herrera-Alvarez S, Jimenez-Ferrer JE, Zamilpa A, Roman-Ramos R, Ponce-Monter H, Tortoriello J. Clinical effects produced by a standardized herbal medicinal product ofHibiscus sabdariffa on patients with hypertension. A randomized, double-blind, lisinopril-controlled clinical trial. Planta Med. 2007;73:6–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17315307

- Hopkins AL, Lamm MG, Funk J, Ritenbaugh C. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. in the treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia: a comprehensive review of animal and human studies. Fitoterapia. 2013;85:84-94. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2013.01.003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3593772/

- Adegunloye BJ, Omoniyi JO, Owolabi OA, Ajagbonna OP, Sofola OA, Coker HA Mechanisms of the blood pressure lowering effect of the calyx extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa in rats. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1996;25:235–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10457797

- Owolabi OA, Adegunloye BJ, Ajagbona OP, Sofola OA, Obiefuna PCM Mechanism of relaxant effect mediated by an aqueous extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa petals in isolated rat aorta. Pharm Biol. 1995;33:210–4.

- Jonadet M, Bastide J, Bastide P, Boyer B, Carnat AP, Lamaison JL [In vitro enzyme inhibitory and in vivo cardioprotective activities of hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.)]. J Pharmacie Belgi. 1990;45:120–4.

- Onyenekwe PC, Ajani EO, Ameh DA, Gamaniel KS Antihypertensive effect of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) calyx infusion in spontaneously hypertensive rats and a comparison of its toxicity with that in Wistar rats. Cell Biochem Funct. 1999;17:199–206. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10451541

- Sacanella E, Vasquez-Agell M, Mena MP, Antúnez E, Fernández-Solá J, Nicolás JM, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Ros E, Estruch R Down-regulation of adhesion molecules and other inflammatory biomarkers after moderate wine consumption in healthy women: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1463–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17991660

- Hertog MG, Feskens EJ, Hollman PC, Katan MB, Kromhout D Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet. 1993;342:1007–11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8105262

- Ali BH, Al Wabel N, Blunden G Phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxological aspects of Hibiscus sabdariffa L: a review. Phytother Res. 2005;19:369–75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16106391

- Manach C, Williamson G, Morand C, Scalbert A, Remesy C Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in human. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:S230–42.

- Herrera-Arellano A, Flores-Romero S, Chavez-Soto MA, Tortoriello J Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa in patients with mild to moderate hypertension: a controlled and randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:375–82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15330492

- The effectiveness of Hibiscus sabdariffa in the treatment of hypertension: a systematic review (Structured abstract). Phytomedicine.2010;17(2):83‐86. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0944711309002293

- Gurrola-Diaz CM, Garcia-Lopez PM, Sanchez-Enriquez S, Troyo-Sanroman R, Andrade-Gonzalez I, Gomez-Leyva JF. Effects ofHibiscus sabdariffa extract powder and preventive treatment (diet) on the lipid profiles of patients with metabolic syndrome (MeSy) Phytomedicine. 2010;17:500–505 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19962289

- Kuriyan R, Kumar D, R R, Kurpad A. An evaluation of the hypolipidemic effect of an extract ofHibiscus sabdariffa leaves in hyperlipidemic Indians: a double blind, placebo controlled trial, BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010;10:27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2906418/

- Mohagheghi A, Maghsoud S, Khashayar P, Ghazi-Khansari M. The effect ofHibiscus sabdariffa on lipid profile, creatinine, and serum electrolytes: A randomized clinical trial. ISRN Gastroenterology. 2011;2011:4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3168576/

- Lin T-L, Lin H-H, Chen C-C, Lin M-C, Chou M-C, Wang C-J. Hibiscus sabdariffa extract reduces serum cholesterol in men and women. Nutr. Res. 2007;27:140–145.

- Kuriyan R, Kumar D, R R, Kurpad A. An evaluation of the hypolipidemic effect of an extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa leaves in hyperlipidemic Indians: a double blind, placebo controlled trial, BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010;10:27 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2906418/

- Mohagheghi A, Maghsoud S, Khashayar P, Ghazi-Khansari M. The effect ofHibiscus sabdariffa on lipid profile, creatinine, and serum electrolytes: A randomized clinical trial. ISRN Gastroenterology. 2011;2011:4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3168576/

- Herrera-Arellano A, Miranda-Sanchez J, Avila-Castro P, Herrera-Alvarez S, Jimenez-Ferrer JE, Zamilpa A, Roman-Ramos R, Ponce-Monter H, Tortoriello J. Clinical effects produced by a standardized herbal medicinal product ofHibiscus sabdariffa on patients with hypertension. A randomized, double-blind, lisinopril-controlled clinical trial. Planta Med. 2007;73:6–12.

- Jones P, Kafonek S, Laurora I, Hunninghake D. Comparative dose efficacy study of atorvastatin versus simvastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia (the CURVES study) Am. J. Cardiol. 1998;81:582–587 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9514454

- Kuriyan R, Kumar D, R R, Kurpad A. An evaluation of the hypolipidemic effect of an extract ofHibiscus sabdariffa leaves in hyperlipidemic Indians: a double blind, placebo controlled trial, BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010;10:27.

- Mohagheghi A, Maghsoud S, Khashayar P, Ghazi-Khansari M. The effect ofHibiscus sabdariffa on lipid profile, creatinine, and serum electrolytes: A randomized clinical trial. ISRN Gastroenterology. 2011;2011:4

- Lin T-L, Lin H-H, Chen C-C, Lin M-C, Chou M-C, Wang C-J. Hibiscus sabdariffa extract reduces serum cholesterol in men and women. Nutr. Res. 2007;27:140–145

- Effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. on serum lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013 Nov 25;150(2):442-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.042. Epub 2013 Oct 10. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378874113006892