Infrapatellar bursitis

Infrapatellar bursitis also known as clergyman’s knee, is the inflammation of the infrapatellar bursa around the insertion of the distal patellar tendon, which is located just below the kneecap.

Infrapatellar bursitis may be:

- Superficial or subcutaneous: anterior to the distal patellar tendon

- Deep: posterior to the distal patellar tendon, in the region of the infrapatellar fat pad (Hoffa’s fat pad).

Bursa, which is a synovium-lined, sac-like structure found throughout the body near bony prominences and between bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. There are 11 bursae in each knee and their function is to facilitate movement in the musculoskeletal system, creating a cushion between tissues that move against one another 1. The most common bursa to become inflammed are the ones located over the kneecap (prepatellar bursa also known as “housemaid’s knee”).

Bursitis is a swelling or inflammation of a bursa, is a relatively common occurrence with a wide range of causes. Bursitis may be caused by trauma (acute or chronic), inflammatory disorders (gout, pseudogout, or rheumatoid arthritis), overuse injury, or infection 2. There have been many associations drawn between various occupations and their predisposition for specific types of superficial bursitis due to chronic, repetitive microtrauma 3. Infrapatellar bursitis may be a component of Osgood-Schlatter disease. When bursitis occurs, the bursa enlarges with fluid, and any movement against or direct pressure upon the bursa will precipitate pain for the patient. The name bursitis itself is often a misnomer, as not all forms of bursitis are due to a primary inflammatory process but are rather a swelling of the bursa due to a noxious stimulus 4.

Two forms of bursitis exist, chronic and acute, and the presentations of each will manifest differently from one another. A detailed medical history, as well as an understanding of the patient’s daily routine, will help the clinician differentiate the 2 types of bursitis from each other and from other diagnoses. Acute bursitis typically arises from trauma, infection, or crystalline joint disease, while chronic bursitis is more likely the result of inflammatory arthropathies and repetitive pressure/overuse, or “microtraumas.” In acute bursitis, patients generally present with pain on palpation of the bursa. The range of motion of the involved joint may be decreased secondary to pain. Active motion involving the affected bursa also elicits pain; however, this is dependent on the location of the bursa and the biomechanics involved in moving the bones, muscles, and tissues around the bursa. For instance, many patients will experience pain with active motion but with passive motion. When the surrounding muscles are not activated and therefore not compressing the bursa, there is little to no pain. Some acute bursitis will produce pain with flexion of the affected joint, but there will be no pain on extension (these findings are commonly seen with prepatellar and olecranon bursitis).

Contrary to the physical exam findings in acute bursitis, chronic bursitis is often painless. The bursa itself has had time to expand to accommodate the increased fluid, and the result is significant swelling and thickening of the bursa. An examination of the skin is very importation in the evaluation of acute or chronic bursitis. The skin should be evaluated for trauma, erythema, and warmth. One study found that a temperature increase of just 2.2 degrees centigrade between the skin overlying the affected bursa compared to that overlying the unaffected, contralateral bursa was highly sensitive and specific for septic bursitis. However, deep bursitis, even when acute, may produce no tenderness with palpation of the overlying structures, nor any obvious skin changes. Lastly, musculoskeletal imbalances or certain anatomic variants are sometimes associated with the development of bursitis. Decreased core strength and chronic back pain can exacerbate trochanteric bursitis, which itself is often precipitated by gluteus minimus or medius tendinopathy, while mechanical factors such as pes planus and genu valgum are risk factors for the development of pes anserine bursitis.

The vast majority of bursitis will heal on its own 1. However, there are several modalities for improving the patient’s pain and ensuring a return to complete functionality of the affected area. Conservative treatment involves the use of rest, ice, compression, and elevation for symptomatic improvement.

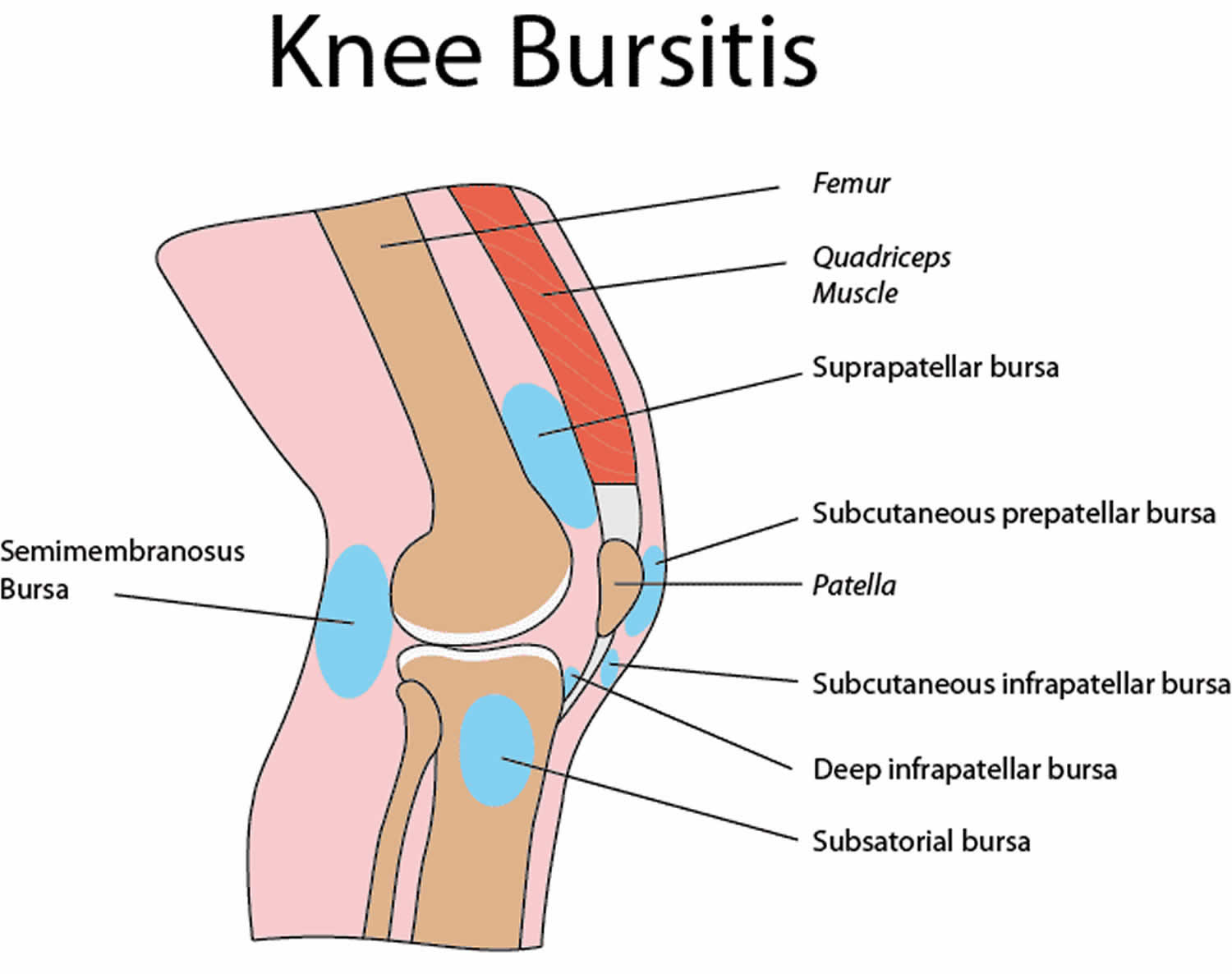

Figure 1. Knee bursitis

Infrapatellar bursitis causes

Infrapatellar bursitis can result from:

- A direct force to your knee

- Frequent falls on your knee

- Too much kneeling

- Bacterial infection of the bursa

- Existing osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis or gout in your knee.

The most common cause is prolonged pressure, whereby the bursa is stressed between a hard surface and bony prominence. Examples of prolonged pressure causing bursitis include students who frequently rest their elbows on their desk and people who work on their knees without adequate padding. Likewise, repetitive motions can also irritate the bursa and result in bursitis. The second most common cause of bursitis is trauma when direct pressure is applied to the bursa. Often the patient will not be able to recall the inciting incident as it may have seemed benign at the time.

Traumatic bursitis puts the patient at risk for septic bursitis, which is most often caused by direct penetration of the bursa through the skin. Septic bursitis can also be provoked through the hematogenous spread; however, due to the relatively poor blood supply to the bursa, this is rare. Staphylococcus aureus causes the majority of septic bursitis. Another important cause of bursitis is autoimmune conditions and systemic inflammatory conditions, as well as arthropathies, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, spondyloarthropathy, and gout. Lastly, bursitis can be idiopathic in origin, and septic bursitis, in particular, can be induced by invasive procedures 5.

Risk factors for infrapatellar bursitis

You can be at increased risk of developing knee bursitis due to:

- Excessive kneeling – People who work on their knees alot of the time, like gardeners and plumbers, are at increased risk of knee bursitis. Some common nicknames for this condition include Housemaid’s knee and Vicar’s or preacher’s knee.

- Obesity and osteoarthritis – Often obese women with osteoarthritis are more likely to develop knee bursitis

- Certain sports – Those that involve alot of falling, especially on the knee. These include volleyball and wrestling

- Impaired immune system – If you’re immune system is weak either due to disease or medications, you can have a greater risk of infectious (septic) knee bursitis. Some conditions include cancer, HIV, diabetes and systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE)

Infrapatellar bursitis symptoms

The main symptoms you may experience in your knee include:

- A hot knee

- A swollen appearance that occurs quickly. This may limit the motion of your knee.

- A painful knee, especially when moved or when pressure is put on it.

- If you have an infection, you might get a fever.

Infrapatellar bursitis complications

There is a very small chance that an inflammed bursa can become infected. Infection of the bursa is quite rare but it is an important complication that can arise. If you have an infected bursa you may experience redness, swelling, pain and heat in the area. If this occurs you need to contact your doctor immediately.

Complications of traumatic bursitis can include repeated irritation or injury, and persistent pain.

Infrapatellar bursitis diagnosis

Usually your doctor can diagnose infrapatellar bursitis clinically without any imaging and without further studies; however, imaging plays a role in the diagnosis and management of bursitis. Other tests may be done to rule out other conditions.

Imaging tests

These tests may be ordered for you

- X-ray – This can’t be used to look at bursa but can detect a fracture, tumor or arthritis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – This can be used to look at the soft tissue in your knee (eg ligaments, tendons)

- Ultrasound – This can be used to visualize swelling in your knee.

Imaging can be helpful to narrow down the differential diagnosis or even provide a precise answer in cases of diagnostic uncertainty. Plain film imaging of the affected joint or bursa should be considered in cases where there is a history of trauma or concern for foreign body or fracture causing swelling or pain. MRI can be used to evaluate the deeper bursa, as can ultrasound which has the added benefit of showing real-time images within a joint or area surrounding the bursa and can be used to observe changes with active and passive movement.

Ultrasound is particularly helpful for visualizing cobblestoning of the fat overlying a bursa, which can help differentiate cellulitis from infectious bursitis. Color Doppler can likewise be used to show signs of infection, such as hyperemia of the bursa and the surrounding tissues.

Aspiration

This can be done if your doctor believes you may have an infection or gout in the bursa. Your doctor will use a needle to drain some fluid for testing.

Aspiration of the inflamed bursa can be helpful when there is a question of septic bursitis or bursitis secondary to crystalline disease. Aspirated fluid should be sent for cell count, Gram stain and culture, glucose, and analysis for crystals. A white blood cell count of less than 500/mm3 from the aspirated fluid is consistent with noninfectious and noncrystalline bursitis 6.

Infrapatellar bursitis treatment

There are a few options for treatment. The first steps include:

- Resting your knee

- Applying ice

- Applying compression

- Elevating your knee

Some active treatments consist of the following.

- Aspiration – Your doctor may directly drain the bursa with a needle and syringe to reduce excess fluid and treat inflammation.

In bursitis caused by systemic inflammatory conditions, it is important that the physician treats the underlying condition. For septic bursitis, systemic antibiotics with activity against gram-positive organisms are the first line therapy. The majority of patients with septic bursitis can be treated as an outpatient with oral antibiotics, and admission is only required if systemic or whole-joint involvement is suspected, or if the patient appears unstable. For certain recalcitrant cases, the bursa can be excised surgically, usually by endoscopic or arthroscopic procedures.

Medications

- Corticosteroid injection – This can be injected directly into the affected site to reduce inflammation. Local injections of corticosteroid are not recommended for the superficial bursa, however, as this carries an increased risk of iatrogenic septic bursitis, local tendon injury, skin atrophy, or draining sinus tracts. Another danger of corticosteroid injections is that it may improve pain and therefore, delay the diagnosis of another condition, in which there is an optimal time frame for surgical repair. In general, the evidence supporting the use of corticosteroid injections for chronic bursitis is lacking, and a recent study suggested no benefit.

- Antibiotics – The doctor may prescribe you antibiotics if infection is suspected.

Allied health

- Physiotherapy – You may be referred to a physiotherapist to have some exercise therapy which may alleviate pain and reduce your risk of having recurring episodes of knee bursitis. Physical therapy and range of motion exercises play a role in increasing the strength of the muscles that support the area around the bursa.

Surgery

This option may be chosen if you have severe chronic bursitis which hasn’t responded to other treatments. This involves surgically removing your bursa.

References- Williams CH, Sternard BT. Bursitis. [Updated 2019 Sep 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513340

- Common Superficial Bursitis. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Feb 15;95(4):224-231. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0215/p224.html

- Baumbach S. F., Lobo C. M., Badyine I., Mutschler W., Kanz K. G. Prepatellar and olecranon bursitis: literature review and development of a treatment algorithm. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2014;134(3):359–370. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1882-7

- Walter WR, Burke CJ, Adler RS. Ultrasound-Guided Therapeutic Scapulothoracic Interval Injections. J Ultrasound Med. 2019 Jul;38(7):1899-1906.

- Situ-LaCasse E, Grieger RW, Crabbe S, Waterbrook AL, Friedman L, Adhikari S. Utility of point-of-care musculoskeletal ultrasound in the evaluation of emergency department musculoskeletal pathology. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(4):262-266.

- Chen Y, Yang J, Wang L, Wu Y, Qu J. [Explanation on Evidence-based Guidelines of Clinical Practice with Acupuncture and Moxibustion: Periarthritis of Shoulder]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2017 Sep 12;37(9):991-4.