What is laparotomy

Laparotomy is a major surgical procedure that involves cutting into the abdomen to gain access to the peritoneal cavity 1. Usually, a standard laparotomy is a cut made in the midline along the linea alba. The indication for a laparotomy is to gain sufficient access into the abdominal cavity to carry out a necessary operation. However, with recent advances in technology, surgery has progressed into the era of laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery as this is considered minimally invasive to patients and has benefits over the traditional open laparotomy approach such as reduced hospital stay, reduced post-operative pain, and decreased cosmetic scarring 1. However, there are still many circumstances where the laparotomy is indicated such as emergency situations where quick abdominal access is needed to stabilize the patient. In the elective setting, a laparotomy may be required if keyhole surgery is not sufficient to gain the necessary access to the viscera. In the case of a trauma laparotomy, a quick large cut in the midline is needed so that intra-abdominal packing can be undertaken in order to control hemorrhage.

Laparotomy is also used to diagnose and treat female pelvic conditions such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids, ovarian cysts, scar tissue (adhesions) and ectopic pregnancy. Laparotomy is less commonly used to explore the source of abdominal problems.

In brief, indications for a laparotomy include the following:

- Blunt abdominal trauma

- Hemorrhage/hemoperitoneum

- Perforated viscus

- Peritonitis

- Intestinal obstruction with hugely distended bowel loops, making a successful laparoscopic intervention unlikely

- Large specimen extraction, e.g., Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Multiple previous abdominal operations, making extensive adhesions likely

- Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding that is not controlled by endoscopic intervention or embolization

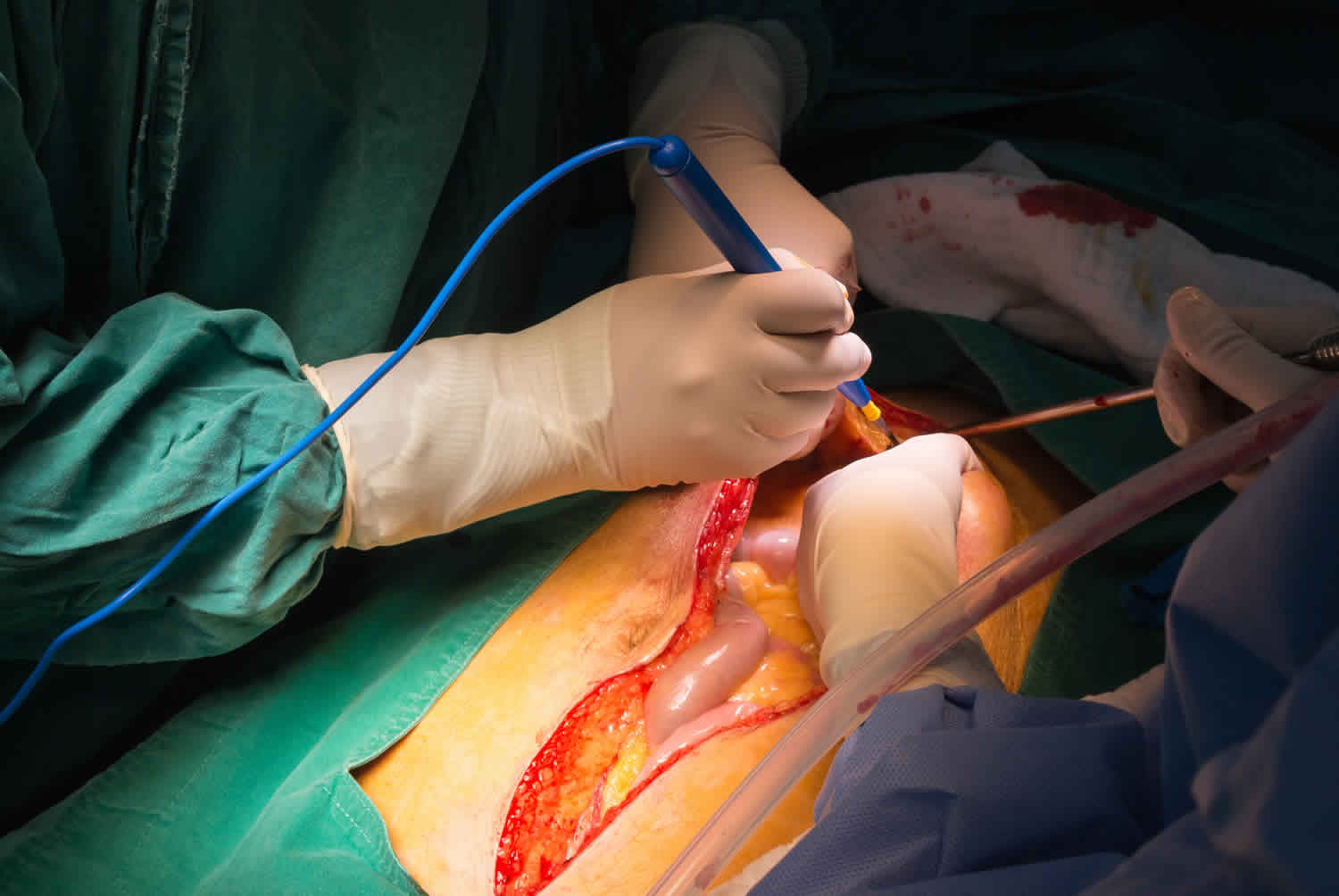

Figure 1. Laparotomy

What is exploratory laparotomy

Your health care provider may recommend a exploratory laparotomy if imaging tests of the abdomen, such as x-rays and CT scans, have not provided an accurate diagnosis.

Exploratory laparotomy is surgery to look at the organs and structures in your belly area (abdomen). This includes your:

- Appendix

- Bladder

- Gallbladder

- Intestines

- Kidney and ureters

- Liver

- Pancreas

- Spleen

- Stomach

- Uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries (in women)

Exploratory laparotomy is done while you are under general anesthesia. This means you are asleep and feel no pain.

The surgeon makes a cut into the abdomen and examines the abdominal organs. The size and location of the surgical cut depends on the specific health concern.

A biopsy can be taken during the procedure.

Exploratory laparotomy may be used to help diagnose and treat many health conditions, including:

- Cancer of the ovary, colon, pancreas, liver

- Endometriosis

- Gallstones

- Hole in the intestine (intestinal perforation)

- Inflammation of the appendix (acute appendicitis)

- Inflammation of an intestinal pocket (diverticulitis)

- Inflammation of the pancreas (acute or chronic pancreatitis)

- Liver abscess

- Pockets of infection (retroperitoneal abscess, abdominal abscess, pelvic abscess)

- Pregnancy outside of the uterus (ectopic pregnancy)

- Scar tissue in the abdomen (adhesions)

Laparotomy vs Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a surgical technique in which a lighted viewing instrument (laparoscope) is inserted into the lower abdomen through a small incision, usually made below your belly button. The abdomen is inflated with gas injected through a needle, which pushes the wall of the abdomen away from the organs so the doctor can see them more clearly.

Laparoscopy may be used for both diagnosis and treatment. Incisions may be made so that other instruments, such as cutting devices or lasers, can be inserted to treat certain problems. With laparoscopy, the doctor can identify diseased organs, take tissue samples for biopsy, and remove abnormal growths.

Laparoscopy is known as minimally invasive surgery. It allows for shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, less pain, and smaller scars than traditional (open) laparotomy.

Laparoscopy may allow a person to avoid more invasive open surgery that uses larger incisions. Compared to open laparotomy, it leaves smaller scars, is often less risky, and usually requires a shorter recovery period. If possible, laparoscopy will be done instead of laparotomy.

Laparoscopy is often used to diagnose and treat problems in the female reproductive organs, such as endometriosis, infertility, or tubal pregnancy. Tubal ligation (female sterilization) can also be done with laparoscopic surgery.

Laparoscopy may be used for a variety of procedures in both men and women, such as to remove the gallbladder.

Laparoscopic surgery may be used to diagnose:

- Tumors and other growths

- Blockages

- Unexplained bleeding

- Infections

For women, laparoscopy may be used to diagnose and/or treat:

- Fibroids, growths that form inside or outside the uterus. Most fibroids are noncancerous.

- Ovarian cysts, fluid-filled sacs that form inside or on the surface of an ovary.

- Endometriosis, a condition in which tissue that normally lines the uterus grows outside of it.

- Pelvic prolapse, a condition in which the reproductive organs drop into or out of the vagina.

Laparoscopic surgery may also be used to:

- Remove an ectopic pregnancy, a pregnancy that grows outside the uterus. A fertilized egg can’t survive an ectopic pregnancy. It can be life threatening for a pregnant woman.

- Perform a hysterectomy, the removal of the uterus. A hysterectomy may be done to treat cancer, abnormal bleeding, or other disorders.

- Perform a tubal ligation, a procedure used to prevent pregnancy by blocking a woman’s fallopian tubes.

- Treat incontinence, accidental or involuntary urine leakage.

Laparoscopic surgery is sometimes used when a physical exam and/or imaging tests, such as x-rays or ultrasounds, don’t give enough information to make a diagnosis.

Figure 2. Laparoscopy (laparoscopic surgery)

Laparotomy myomectomy

Myomectomy is a surgical procedure to remove uterine fibroids — also called leiomyomas. These common noncancerous (benign) growths appear in the uterus, usually during childbearing years, but they can occur at any age.

The surgeon’s goal during myomectomy is to take out symptom-causing fibroids and reconstruct the uterus. Unlike a hysterectomy, which removes your entire uterus, a myomectomy removes only the fibroids and leaves your uterus intact.

Women who undergo myomectomy report improvement in fibroid symptoms, including heavy menstrual bleeding and pelvic pressure.

Your doctor might recommend myomectomy for fibroids causing symptoms that are troublesome or interfere with your normal activities. If you need surgery, reasons to choose a myomectomy instead of a hysterectomy for uterine fibroids include:

- You plan to bear children

- Your doctor suspects uterine fibroids might be interfering with your fertility

- You want to keep your uterus

Laparotomy myomectomy

In laparotomy myomectomy or abdominal myomectomy, your surgeon makes an open abdominal incision to access your uterus and remove fibroids. Your surgeon enters the pelvic cavity through one of two incisions:

- A horizontal bikini-line incision that runs about an inch (about 2.5 centimeters) above your pubic bone. This incision follows your natural skin lines, so it usually results in a thinner scar and causes less pain than a vertical incision does. It may be only 3 to 4 inches (8 to 10 centimeters), but may be much longer. Because it limits the surgeon’s access to your pelvic cavity, a bikini-line incision may not be appropriate if you have a large fibroid.

- A vertical incision that starts in the middle of your abdomen and extends from just below your navel to just above your pubic bone. This gives your surgeon greater access to your uterus than a horizontal incision does and it reduces bleeding. It’s rarely used, unless your uterus is so big that it extends up past your navel.

Laparotomy myomectomy risks

Myomectomy has a low complication rate. Still, the procedure poses a unique set of challenges. Risks of myomectomy include:

- Excessive blood loss. Many women already have low blood counts (anemia) due to heavy menstrual bleeding, so they’re at a higher risk of problems due to blood loss. Your doctor may suggest ways to build up your blood count before surgery. During myomectomy, surgeons take extra steps to avoid excessive bleeding, including blocking flow from the uterine arteries and injecting medications around fibroids to cause blood vessels to clamp down. Studies suggest blood loss is similar between a myomectomy and hysterectomy. Also, with both, blood loss is higher with a larger uterus.

- Scar tissue. Incisions into the uterus to remove fibroids can lead to adhesions — bands of scar tissue that may develop after surgery. Outside the uterus, adhesions could entangle nearby structures and lead to a blocked fallopian tube or a trapped loop of intestine. Rarely, adhesions may form within the uterus and lead to light menstrual periods and difficulties with fertility (Asherman’s syndrome). Laparoscopic myomectomy may result in fewer adhesions than abdominal myomectomy (laparotomy).

- Pregnancy or childbirth complications. A myomectomy can increase certain risks during delivery if you become pregnant. If your surgeon had to make a deep incision in your uterine wall, the doctor who manages your subsequent pregnancy may recommend cesarean delivery (C-section) to avoid rupture of the uterus during labor, a very rare complication of pregnancy. Fibroids themselves are also associated with pregnancy complications.

- Rare chance of hysterectomy. Rarely, the surgeon must remove the uterus if bleeding is uncontrollable or other abnormalities are found in addition to fibroids.

- Rare chance of spreading a cancerous tumor. Rarely, a cancerous tumor can be mistaken for a fibroid. Taking out the tumor, especially if it’s broken into little pieces to remove through a small incision, can lead to spread of the cancer. The risk of this happening increases after menopause and as women age.

Strategies to prevent possible surgical complications

To minimize risks of myomectomy surgery, your doctor may recommend:

- Iron supplements and vitamins. If you have iron deficiency anemia from heavy menstrual periods, your doctor might recommend iron supplements and vitamins to allow you to build up your blood count before surgery.

- Hormonal treatment. Another strategy to correct anemia is hormonal treatment before surgery. Your doctor may prescribe a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist, birth control pills, or other hormonal medication to stop or decrease your menstrual flow. When given as therapy, a GnRH agonist blocks the production of estrogen and progesterone, stopping menstruation and allowing you to rebuild hemoglobin and iron stores.

- Therapy to shrink fibroids. Some hormonal therapies, such as GnRH agonist therapy, can also shrink your fibroids and uterus enough to allow your surgeon to use a minimally invasive surgical approach — such as a smaller, horizontal incision rather than a vertical incision, or a laparoscopic procedure instead of an open procedure. In most women, GnRH agonist therapy causes symptoms of menopause, including hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness. However, these discomforts end after you stop taking the medication. Treatment generally occurs over several months before surgery. Evidence suggests that not every woman should take GnRH agonist therapy before myomectomy. GnRH agonist therapy may soften and shrink fibroids enough to interfere with their detection and removal. The cost of the medication and the risk of side effects must be weighed against the benefits. Drugs that modulate progesterone action, such as ulipristal (ella), also may decrease symptoms and shrink fibroids. Outside the United States, ulipristal is approved for three months of therapy before a myomectomy.

Laparotomy procedure

Before the laparotomy procedure

You will visit with your doctor and undergo medical tests before your surgery. Your doctor will:

- Do a complete physical exam.

- Make sure other medical conditions you may have, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or heart or lung problems are under control.

- Perform tests to make sure that you will be able to tolerate the surgery.

- If you are a smoker, you should stop smoking several weeks before your surgery. Ask your provider for help.

Tell your doctor:

- If you’re on medications, ask your doctor if you should change your usual medication routine in the days before surgery. Tell your doctor about any over-the-counter medications, vitamins or other dietary supplements that you’re taking.

- If you have been drinking a lot of alcohol, more than 1 or 2 drinks a day

- If you might be pregnant

During the week before your laparotomy surgery:

- You may be asked to temporarily stop taking blood thinners. Some of these are aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), vitamin E, warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or ticlopidine (Ticlid).

- Ask your doctor which drugs you should still take on the day of your surgery.

- Prepare your home for your return from the hospital.

On the day of your laparotomy surgery:

- You’ll need to fast — stop eating or drinking anything — in the hours before your surgery. Follow your doctor’s recommendation on the specific number of hours.

- Take medicines your provider told you to take with a small sip of water.

- Arrive at the hospital on time.

Laparotomy procedure

You will be given a general anaesthetic, so you won’t be awake during the surgery. A cut will be made in your abdomen, so the doctor can look inside. Other procedures might be done at the same time, depending on the type of problem. You should discuss these possibilities with your doctor.

In laparotomy surgery, your surgeon makes an open abdominal incision to access your abdomen. Your surgeon enters the abdominal cavity through the following incisions:

Midline/Median approach

The most common procedure is the midline laparotomy where an incision is made down the middle of the abdomen along the linea alba. The size of the incision can be limited depending on the site of the pathology. For example, an upper gastrointestinal problem may not require a lower midline incision. However, the decision can always be extended lengthways to gain more access if needed. Some surgeons will curve their incision around the umbilicus; however, a more cosmetically pleasing technique includes retracting the umbilicus away from the midline using a Littlewoods clamp to keep the incision vertically straight. The incision is usually made with a scalpel, although cutting cautery is also an option for the skin cut. Then, coagulative cautery is used to dissect the subcutaneous fat and superficial fascial layers down to the rectus sheath. As the linea alba is where the aponeuroses converge, this is an avascular plane, and therefore muscle should not be encountered. Once dissected through the rectus sheath (anterior and posterior components), two Fraser-kelly clips can be applied to the peritoneum and lifted up. McIndoe scissors then cut between the clips which should allow access into the peritoneal cavity. The surgeon then sticks his/her fingers into the hole created and widens the incision in the peritoneum, taking care not to injure any underlying structures such as the bowel.

Paramedian approach

This approach is similar to the midline approach; however, the vertical incision is made lateral to the linea alb to allow access to lateral/retroperitoneal structures such as the kidneys and adrenal glands. The linea semilunaris, which is the lateral border of the rectus, is usually the landmark used. The paramedian incision increases the possibility of muscle atrophy, hematoma, and nerve injury because it is more likely for the surgeon to encounter various vessels and nerves supplying the muscles of the abdominal wall.

Transverse approach

As the name suggests, this approach uses a transverse incision lateral to the umbilicus (compared to the previous approaches which are vertical). This is a common approach as it causes least damage to the nerve supply to the abdominal muscles as it follows a dermatome, and heals well. The incised rectus abdominis heals producing a new tendinous intersection. An example of where this is used is in an open right hemicolectomy.

Pfannenstiel approach

Pfannenstiel incisions are made 5 cm superior to the pubis symphysis in a curved transverse fashion to gain access to the pelvic cavity When performing this incision, care must be taken not to perforate the bladder as the fascia around the bladder is thin. Intestinal loops can also be commonly encountered here. This incision is commonly used in emergency cesarean sections as well as a site of extraction for pathological specimens that have been excised elsewhere within the abdominal cavity.

Subcostal approach

This incision starts inferior to the xiphoid process and extends inferior and parallel to the costal margin. The incision should be at least two fingerbreadths below the costal margin to reduce the risk of post-operative pain and poor wound healing. It is used to access the gallbladder and liver when performed on the right-hand side and the spleen when on the left-hand side. If both left and right subcostal incisions are joined together in the midline, they form a rooftop incision.

Laparotomy recovery time

A laparotomy is a significant operation, and recovery will take time. When you wake, you might have a catheter (a tube in your bladder) to help you pass urine. You will be given medicine for pain.

It may be a while before you can eat and drink normally, and you will probably need time off work to recover. You might have stitches or staples in the wound that will need to be removed. Your doctor can advise you about having this done.

You will probably stay in hospital for at least a few days after the surgery.

You should be able to start eating and drinking normally about 2 to 3 days after the laparotomy surgery. How long you stay in the hospital depends on the severity of your problem being treated. Complete recovery after a laparotomy usually takes about 4 weeks.

Open laparotomy risks

Risks of anesthesia and surgery in general include:

- Reactions to medicines, breathing problems

- Bleeding, blood clots, infection

Risks of laparotomy surgery include:

- Incisional hernia

- Damage to organs in the abdomen

Laparotomy complications

Complications of a laparotomy can be site-specific or general but are usually influenced by factors at the time of the operation. As such, it can be classified as patient-related or operator-dependent and, of course, should take into account the operation itself. The following is a broad list of possible complications:

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Bruising

- Seroma/ hematoma

- Wound dehiscence

- Necrosis

- Incisional herniation

- Chronic pain

- Skin numbness

- Fistulation with underlying structures

- Raised intra-abdominal compartment pressure

- Damage to underlying structures

- Poor cosmesis