Lichenoid dermatitis

Lichenoid dermatitis is a histological term that refers to a combination of histological findings that is close to those of lichen planus 1. Lichenoid dermatitis is a form of neurodermatitis, characterized by intense pruritus with exudative, weeping patches on the skin scattered irregularly over most of the body, many of which are of the eczematous type and undergo lichenification. Lichenoid dermatitis describes a skin condition that is microscopically characterized by band-like lymphocytic inflammation with alteration of the epidermal basal layer 2. Lichenification is the thickening of the skin with an exaggeration of the normal skin markings resulting from chronic rubbing and scratching. The term ”lichenoid” refers to papular lesion of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus is the prototype. However, this type of reaction can also be seen skin disorders associated with systemic illnesses like lupus erythematosus and the skin changes of potentially fatal disorders such as graft versus host disease, Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

The histological diagnosis of lichenoid dermatitis is a beginning rather than an end. A search for the underlying clinical disorder requires efforts by both the practitioner and the pathologist.

Interface dermatitis

Lichenoid tissue reaction or interface dermatitis is some of the commonly encountered clinical and histological presentations in dermatology and pathology. The term interface dermatitis refers to the finding in a skin biopsy of an inflammatory infiltrate that abuts or obscures the dermo-epidermal junction.

Frictional lichenoid dermatitis

Frictional lichenoid dermatitis also called Sutton’s summer prurigo or “summertime pityriasis of the elbow and knee” is skin disease that got its name from its appearance of flat topped and often somewhat scaly. Frictional lichenoid dermatitis is a dermatoses seen in children localized to the extensors which has been associated with friction, trauma, sunlight, sand, sports or atopic dermatitis. Frictional lichenoid dermatitis have various causes such friction 3, UV radiation 4 and an underlying atopic state 3. Though frictional lichenoid dermatitis is considered to be associated with atopic dermatitis (eczema), it is at best a minor morphological variant 5 and using the existing diagnostic criterion of atopic dermatitis (eczema) 6, in most cases a “atopic state” has been found, not overt atopic dermatitis (eczema). The consistently reported seasonal association with summers and spring 7 is a pointer against atopic dermatitis (eczema) which usually improves in summers.

Figure 1. Frictional lichenoid dermatitis

Frictional lichenoid dermatitis symptoms

Morphological types of frictional lichenoid dermatitis depends on its severity:

- Mild frictional lichenoid dermatitis:

- Faintly depigmented, pityriasiform lesions, pinhead sized, imperceptibly raised on a dark background

- Moderate frictional lichenoid dermatitis:

- Dull pink lichenoid, thick raised papules, periphery shows flat lesions

- Severe frictional lichenoid dermatitis:

- Crusted papules with itching

The elementary lesion is a lichenoid, globular, angular, papule, discrete and closely aggregated to occasionally forms plaques

Lichenoid dermatitis causes

Lichenoid dermatitis causes:

- Lichen planus:

- hypertropic, atropic, linear, ulcerative, actinic, planopilaris, erythematosus, pemphigoids

- Erythema dyschromicum perstans

- Keratosis lichenoides chronica

- Lupus erythematosus – lichen planus overlap syndrome

- Lichen nitidus

- Lichen striatus

- Lichen planus-like keratosis

- Lichenoid drug eruptions

- Drug induced:

- Fixed drug eruptions

- Erythema multiforme

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis

- Lupus erythematosus

- AIDS interface dermatitis

- Graft versus host disease

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus

- Miscellaneous:

- Poikiloderma

- Pityriasis lichenoides

- Lichenoid purpura

- Lichenoid contact dermatitis

- Late secondary syphilis

- Lichen amyloidosis

- Erythroderma

- Lichen photosensitive / phototoxic dermatoses

- Lupus erythematosus:

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- discoid lupus erythematosus

- subacute lupus erythematosus

- neonatal lupus erythematosus

Lichen planus and lupus erythematosus are the most common and best studied representatives of the lichenoid tissue reaction 8. In lupus erythematosus, basal damage usually is more focal and appears to be secondary, but the events following it are the same. The histologic picture of lichen nitidus is distinctive, but is quite similar to an early lichen planus papule. However, the clinical features of uniform, not enlarging, not confluent round papules, make lichen nitidus a distinctive entity 9. The lichenoid or lichen planus like actinic keratosis, is another example that basal cell damage, though by a neoplastic process, can lead to a typical lichenoid reaction 10. Lichenoid drug reactions caused by an ever increasing list of drugs used in medical therapeutics are the commonest culprit in induction of lichenoid dermatitis or lichenoid photodermatitis 11. Tropical lichen planus or lichen planus actinicus may be sunlight provoked lichen planus or due to direct damage of epidermal basal layer by ultraviolet rays 12.

Lichen planus and its clinical variants

Lichen planus and its variants latter are fairly common, extensively covered dermatosis encountered worldwide. The clinical and histological features are well documented. The lichen planus variants is a classic example of the lichenoid interface dermatitis, and is characterized by the basal cell damage in the form of multiple civatte bodies and a band-like infiltrate on the undersurface of the epidermis along with wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with saw toothed rete-ridges 13. However, individual histopathological variations may be seen in the different clinical types of lichen planus 14 and have been excellently recorded by Weedon. 15. Ulcerative lesions are usually seen on mucous membranes of the oral cavity, glans penis and vulva 16. In such instances, the typical histopathological changes are confined largely to the margins of the ulcer 17.

Lichen nitidus

Unlike lichen planus, asymptomatic lesions having predilection for the upper extremities, chest, abdomen, and male genitalia 18 clinically characterize it. Previously recorded summertime actinic lichenoid eruption (SALE), may well represent the actinic form of lichen nitidus 19. The histopathology is picturesque, a dense, well-circumcised subepidermal infiltrate enclosed by a ”claw-like” rete ridges 20. Overlying epidermis is thinned out with occasional civatte bodies.

Lichen striatus

This, on the other hand, displays papular lesions in a linear, unilateral fashion often following Blaschko’s lines, usually occurring in adolescents especially females 21. Its histopathology is marked by hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, often minute intraepidermal vesicles containing Langerhan’s cells and less dense infiltrate of lymphocyte, histiocytes, and melanophages in the mildly edematous dermal papillae 22. Hard et al. 22, believe that linear lichen planus and lichen striatus are the opposite ends of a spectrum.

Lichen planus-like keratosis

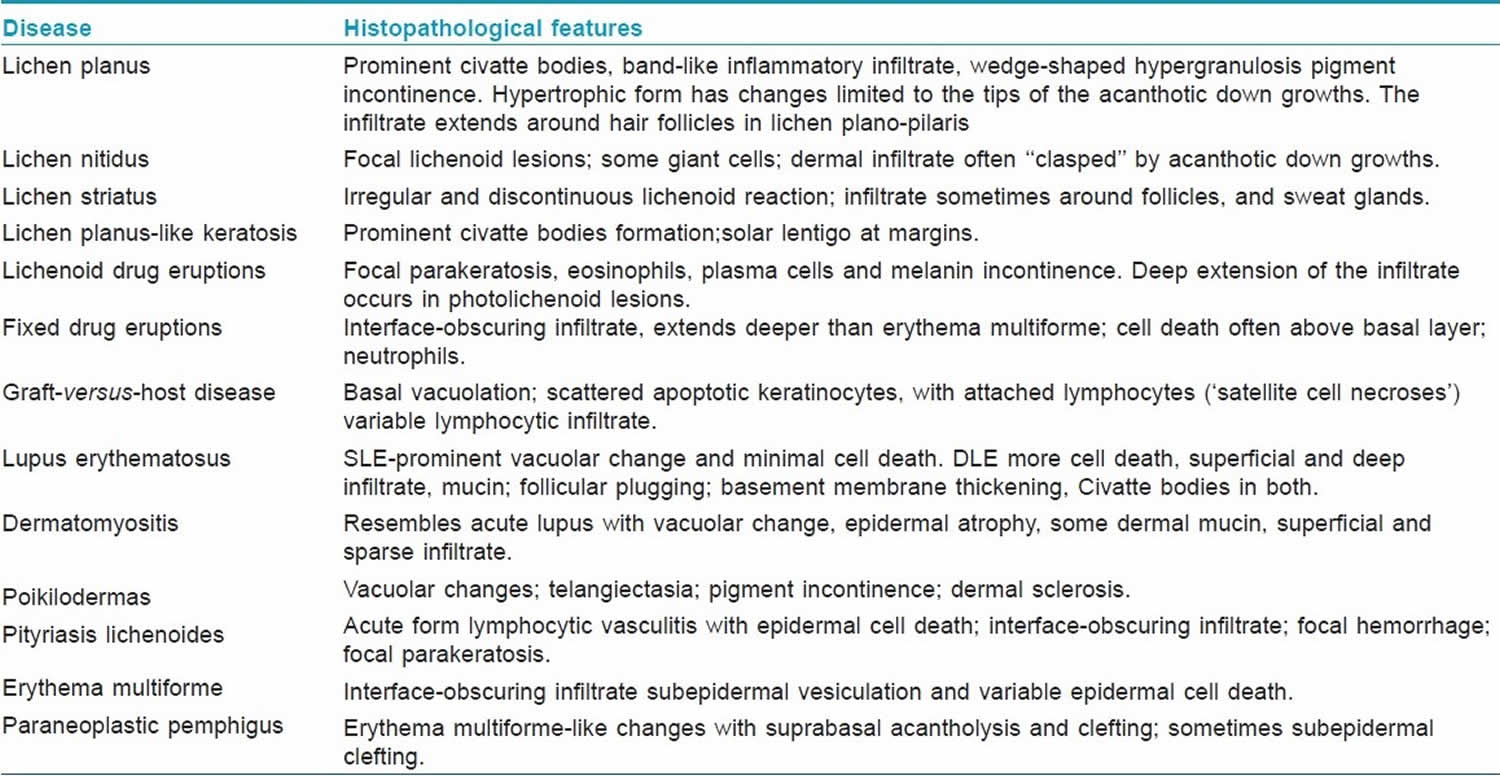

They are benign lichenoid keratosis present as sudden eruption of solitary or a few violaceous, rusty lesions with thin scale usually present on the arms or presternal areas of middle aged/elderly women 23. The microscopic features are pathognomonic characterized by florid lichenoid reaction, prominent pigment incontinence, and numerous civatte bodies. The dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages may also show a few plasma cell and eosinophilis 24. Individual histopathologic variations prompted Jang et al. 25, to classify lichenoid keratosis in three groups, namely, lichen planus-like, seborrheic keratosis-like, and lupus erythematosus-like lichenoid keratosis. The salient histopathological features of the preceding lichenoid interface dermatoses are outlined .

Twenty-nail dystrophy

Trachyonychia, a fascinating clinical condition, was brought to focus 25 years ago. Ever since, it has been sparingly reported. Nonetheless, the condition is well recognized, and its diagnosis is made on the basis of clinical features characterized by26 onset in infancy/childhood, and occasionally in adults. The lesions are fairly representative, and are characterized by the alternating elevation and depression (ridging) and/or pitting, lack of luster, roughening likened to sandpaper, splitting, and change to a muddy grayish-white color. Dystrophy is prominent. Several modes of occurrence have been described including an hereditary component. The confirmation of diagnosis is through microscopic pathology corresponding to endogenous eczema/dermatitis, lichen-planus-like or psoriatic-form. It is a self-limiting condition and may occasionally require intervention.

Drug induced lichenoid dermatitis

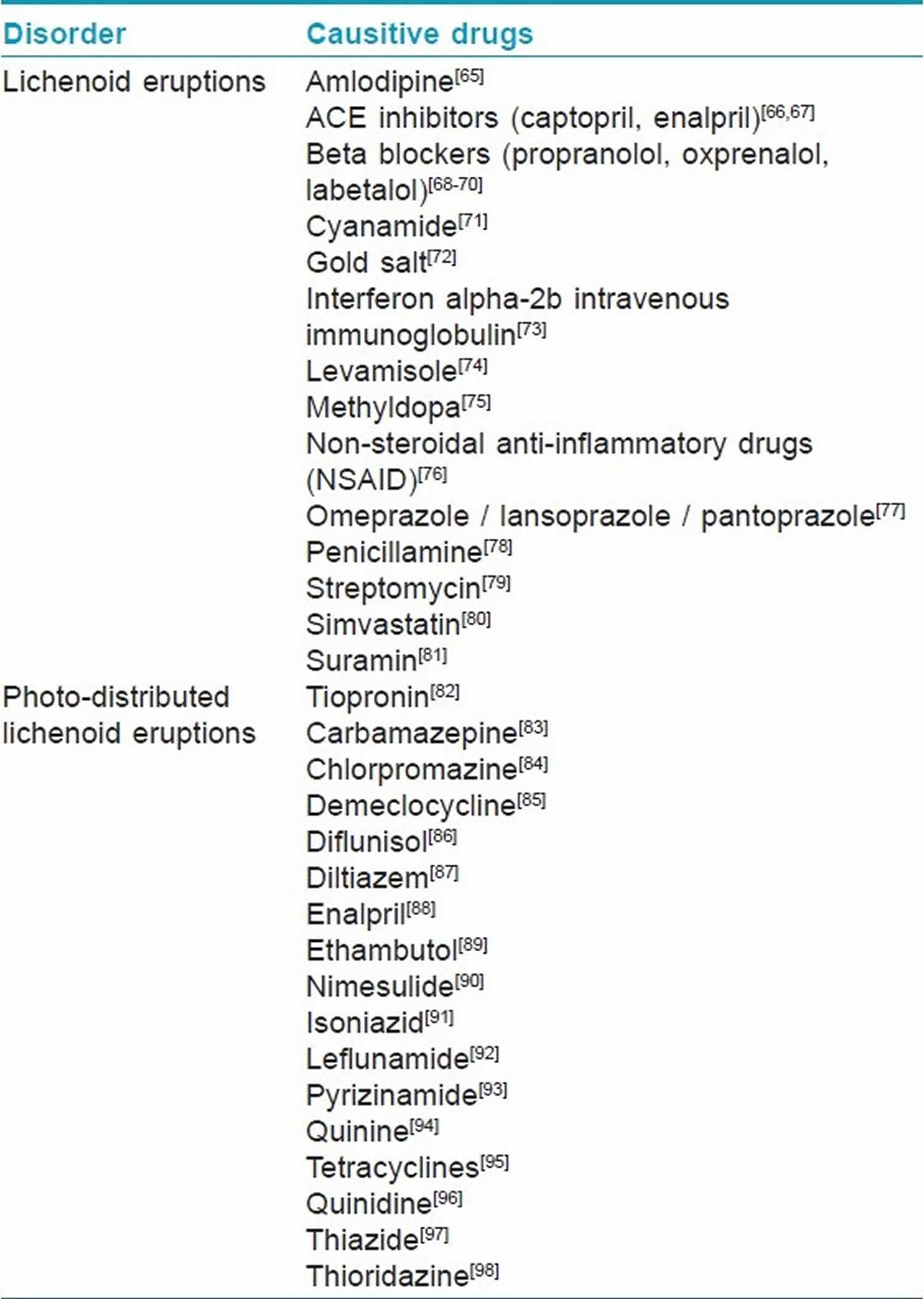

Lichenoid drug eruptions is an often encountered drug reaction to a heterogeneous group of ingested and/or injected drugs used in a wide variety of systemic disorders. Ever since the observation of lichen planus-like eruptions occurring in troops who took mepacrine in the World War II ( Bauer F. Quinacrine hydrochloride drug eruption (topical lichenoid dermatitis). Its early and late sequelae and its malignant potiential: A review. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;4:239-48.)), numerous reports have recorded this entity in response to different drugs (Table 1). Wechsler 27 initially reported photo-lichenoid dermatitis in the year 1954, as a photo allergic reaction to drug(s), presenting a lichenoid pattern on clinical as well as histopathological examination. The lichenoid eruptions/photo-lichenoid eruptions clinically closely mimic lichen planus, but may have some eczematous element and usually leave a pronounced residual pigmentation. Histopathologically, differentiating features of lichenoid eruptions include foci of parakeratosis, mild basal vacuolar changes with a few eosinophils/plasma cells. The degree of melanin incontinence is higher in lichenoid eruption in contrast that of lichen planus 28. However, the dermal infiltrate is less dense and less band-like. Photo-lichenoid eruptions, on the other hand, may closely mimic lichen planus 29.

Table 1. Lichenoid drug eruptions

Fixed drug eruptions

A wide variety of drugs have been incriminated 30. They may probably be induced by drug acting as hapten, binding to keratino/melanocytes producing an immunological reaction, an antibody-dependent cellular cytoid response. Suppressor/cytotoxic lymphocytes attack the drug altered epidermal cells causing the eruption, and thus retain the cutaneous memory in cases of repeated offence by the drug 30. The clinical lesions may mimic lichenoid interface dermatoses 30. The microscopic pathology of fixed drug eruptions (FDE) shows a prominent vacuolar change in the basal cells, civatte bodies, melanin incontinence, and inflammatory infiltrate often comprising neutrophils approximating the dermo-epidermal junction, extending up to mid-epidermis and dermis 30.

Erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis

They are other severe forms of drug eruptions. Histopathology shows changes that of lichenoid dermatitis, conforming to either epidermal, dermal, or mixed pattern. It is characterized by mild-to-moderate lymphocytic infiltrate, a few macrophages, obscuring dermo-epidermal junction, and surrounding the dermal blood vessels up to mid-dermis. Apoptosis with prominent epidermal cell death extending beyond basal cell layer 31 is another salient feature. Toxic epidermal necrolysis, on the other hand, may reveal a sub-epidermal bulla beneath a confluent epidermal necrosis. Lymphocytic infiltrate is sparse, and perivascular. Sweat ducts are often involved, and may show a basal cell apoptosis resulting even in necrosis 32.

It has been a controversial, infrequently encountered entity 15. An increased prevalence and severity of cutaneous photosensitivity has been recognized in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Lichenoid and/or nonlichenoid eczematous are the two distinct clinical manifestations. Burger and Dhar [118] have studied lichenoid photo eruptions in HIV infection. Systemic and cutaneous immune abnormalities may be relevant in their pathogenesis 33. Histopathology largely shows a lichenoid reaction pattern depicting interface changes, resembling those of erythema multiforme or fixed drug eruption 15.

Lichenoid reaction to graft versus host disease

Chronic graft versus host disease occurring after 3 months of transplantation or later may resemble lichenoid reactions, affecting the palms, soles, trunk buttocks, and thighs. Oral ulcers and xerostomia may be its accompaniment. The microscopic pathology of the chronic phase may resemble that of lichen planus albeit marked by a dense inflammatory infiltrate, and prominent pigment incontinence. Small foci of ”columnar epidermal necrosis” may also be a prominent feature 34.

Lichenoid eruptions in paraneoplastic pemphigus

They may either occur independently or on previously blistered skin. They are invariably accompanied by severe stomatitis. As the disease gets chronic or after treatment the lichenoid eruptions may overtake the blistering. Unlike, pemphigus vulgaris, they are often seen on the palms, soles, and over paronychial tissue 35. The microscopic findings resemble erythema multiforme with lichenoid tissue reaction. Dyskeratotic cell at different level of epidermis is another feature. Subepidermal as well as suprabasal cleft depicting acantholysis have also been recorded 36.

Lichenoid dermatitis in lupus erythematosus

A lichenoid reaction pattern in variable permutation and combination is a common denominator. The clinical features and variants of lupus erythematosus (LE) have been extensively recorded 35. Some degree of overlap may be seen in its different clinical variants. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) displays a lichenoid reaction pattern with chiefly a peripilosebaceous/follicular superficial and deep dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Liquefaction degeneration, scattered civatte bodies, hyperkeratosis, atrophic malpighian layer, and keratotic plugging are succinctly observed 37. Direct immunofluorescence of involved skin reveals the deposition of IgG and IgM along the basement membrane zone in most cases. The cutaneous lesions of SLE show vacuolar degeneration of the basement membrane, yet civatte bodies are unusual. Fibrinoid material can be deposited in dermis around capillaries and interstitium, which may cause thickening of the basement membrane zone. Special stains may reveal deposition of mucin. Hematoxyphilic bodies, which are usual in the visceral lesions, are rare in the skin lesions. A positive lupus band test is an additional pointer towards diagnosis, which is invariably positive in involved skin 38.

The subacute lupus erythematosus displays a wide range of clinical expressions and mild systemic/serological abnormalities 35. The histopathological features of cutaneous lesions, however, reveal most of the features seen in discoid lupus but with more basal vacuolar changes, epidermal atrophy, dermal edema and superficial mucin in the former. Compared to discoid lupus, it has less pronounced hyperkeratosis, keratotic plugging, pilo-sebaceous atrophy, basement membrane thickening, and cellular infiltrate 35.

Miscellaneous disorders showing lichenoid dermatitis

Late secondary syphilis

Its histopathology may display a lichenoid reaction pattern, the inflammatory infiltrate formed primarily by plasma cells, which are distributed through out the dermis 39.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

It is an uncommon, self-limited, acrodermatitis of childhood, characterized by an erythematous papular eruptions symmetrically distributed on the face and limbs with mild lymphadenopathy. It is thought to be of viral origin. The histopathologic findings are nonspecific, and include focal parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, superficial perivascular infiltrate, papillary dermal edema, and extravasated red blood cells. Interface changes with some basal vacuolization may be present 40.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV)

They are responsible for various atypical mucocutaneous manifestations in the immunosuppressed population. An altered virus-host cell relationship may be one of the pathomachanisms. Histopathology reveals lichenoid dermatitis. Specific HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV in situ hybridization proved the viral origin of the cutaneous lesions 41.

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA)

It may show a heavy lymphocytic infiltrate obscuring the dermo-epidermal junction with focal epidermal cell death, and confluent epidermal necrosis. A wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate with apex in deep dermis with variable hemorrhage may be diagnostic 42.

Poikilodermatous disorders

They are heterogeneous group of disorders, characterized by erythema, mottled pigmentation and epidermal atrophy, complimented histologically by basal vacuolar changes, melanin incontinence and telangiectasia of superficial dermal vessels 35. The genodermatoses-like Rothmund-Thomson syndrome More Details, Blooms syndrome and dyskeratosis congenital reveal their independent clinical characteristic, and histopathological peculiarities, but with a variable degree of lichenoid reaction. Poikiloderma atrophicans vasculare may represent an early stage of mycosis fungoides 35. Poikiloderma of civatte is now disputed as a distinct entity 43. Some poikilodermas may be related, in some ways to a graft versus host reaction 44.

Dermatomyositis

Skin lesions have shown a spectrum of histopathological changes, varying from sparse perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, edema, mucinous changes in the upper dermis, to full-fledged lichenoid reaction pattern with prominent basal vacuolar changes. Occasional civatte bodies and/or neutorphils can be an accompaniment. Severe cases resemble acute lupus erythematosus. Infrequently poikilodermatous features can be an additional with dilated superficial blood vessels and pigment incontinence. Lupus band test is usually negative, although colloid bodies containing IgM may be a salient feature in papillary dermis 45.

Lichen sclerosus/ lichen sclerosus et atrophicus/balanitis xerotica obliterans/kraurosis vulvae

It is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis that results in white plaques with epidermal atrophy. It appears to begin as an interface dermatitis. Its early lesions may show a heavy infilammatory infiltrate with vacuolar changes, and apoptotic basal changes. As the disease progresses, the infiltrate is eventually pushed downwards by expanding zone of edema and sclerosis 15.

Lichenoid contact dermatitis

It shows a patchy band-like dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes with a few eosinophils and a mild basal spongiosis. It usually results from contact with rubber and chemical used in clothing dyes and wine industries 15.

Progressive pigmented purpuric dermatosis/Schamberg’s disease

It is a chronic discoloration of the skin, which usually affects the legs and often spreads slowly. It may show lichenoid reaction pattern. However, the presence of purpura and deposits of hemosiderin distinguish it from other disorders 15.

Erythroderma and lichen amyloidosis may have prominent pigmented lichenoid tissue reaction 15.

The latter is recognized by hyperpigmented, lichenified and hyperkeratotic well-formed lesions 46. Pathologic changes in the form of acanthotic and hyperkeratotic epidermis is cardinal in lichenoid lesions. Eosinophilic cytoid bodies in the epidermis are diagnostic, following histo-chemical stains like congo-red and crystal violet. The eruption of lymphocyte recovery, initially recorded by Home et al. 47, are now believed to be a form of graft-versus-host disease 48.

Lichen aureus, a variant of pigmented purpuric dermatoses is known for persistent, golden, copper-colored, flat-topped papules that appear suddenly. Minute cutaneous blood vassels are the prime target 49.

Lichen spinulosus

It is characterized by round-to-oval patches of grouped follicular papules with rough keratotic centers 50 may yet be another entity, which requires confirmation by microscopic pathology evident as a keratotic plug consisting of laminated corneocytes, occupying a dilated follicle.

Lichenoid dermatitis pathology

The basal cell damage is a common denominator of these heterogeneous groups of disorders. The term ”interface dermatitis,” often used for lichenoid disorders, denotes that the inflammatory infiltrate along with basal cell damage appear to obscure the dermo–epidermal junction. The epidermal basal cell damage leads to cell death and/or vacuolar changes (liquefactive degeneration). The so-called civatte bodies are damaged epidermal cells with shrunken eosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclear remnants (apoptosis), However, certain disorders show frank necrosis of the epidermis rather than apoptosis. Filamentous degeneration is another type of cell damage which 51, may display none of the above changes. Melanin incontinence is another fall out of the damaged basal cells seen more frequently in drug or solar damage induced dermatoses 52.

Cell-mediated cytotoxicity is regarded as a major mechanism of pathogenesis of lichen planus, as evidenced by T cells being the predominant cells in the inflammatory infiltrate 53. Various factors may precipitate the cell mediated reaction resulting in lichen planus lesions such as, mechanical trauma, systemic drugs, contact sensitivity, infective agents including some viruses 54.

Although the specific antigen of lichen planus is still unclear, the antigen presentation by basal keratinocytes are thought to cause T cell accumulation in the superficial lamina propria, basement membrane disruption, intra-epithelial T-cell migration, and CD8+ cytotoxic cell mediated keratinocyte apoptosis in lichen planus 55.

There is limited data about the role of cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lichen planus, which is mediated by both cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and natural killer (NK) cells. The cytoplasm of cytotoxic cells is enriched with granules composed of the potent cytolytic molecule perforin (pore-forming protein) together with serine esterase (granzymes) 56. Upon contact with the target cell and activation, cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells release perforin and granzymes in a contact zone between target and killer cells. Perforin forms pores in the target cell membrane and thus enables entry of granzymes, responsible for DNA degradation and apoptosis of target cells. Shimizu et al. 57 found a significant role of granzyme B-expressing CD8+ T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Massri et al. 58, found higher expression of cytolytic molecule perforin in lesional lichen planus as well as in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as compared to remission and healthy controls, supporting the hypothesis about the potential role of CD8+ cytolytic effector cells in the exacerbation of disease. Similarly, a variety of clinical and pathologic features uniquely observed in fixed drug eruption lesions can be explained by the presence of CD8+ intraepidermal T cells, with the effector memory phenotype in the fixed drug eruption lesion 59.

The possible mechanism involved in the variability of expression of lichenoid tissue reaction depends on the degree and pattern of expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). Normal epidermis is resistant to interaction with leukocytes because its keratinocytes have low constitutive expression of ICAM-1. In lichen planus the ICAM-1 expression is limited to the basal keratinocytes while in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, there is a diffuse ICAM-1 expression with basal accentuation 60. This pattern is induced by ultraviolet (UV) radiation possibly mediated by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha). The histogenesis of lichenoid interface dermatoses is diverse, and includes both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses 15. Furthermore, recent work has suggested that a number of different lichenoid tissue reaction or interface dermatitis skin disorders share a common inflammatory signaling pathway involving the actions of plasmacytoid dendritic cell-derived interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha). This signaling pathway appears to amplify cytotoxic T cell injury to the epidermal basal cell compartment. The preceding pathway as well as the other cellular and molecular mechanisms that are thought to be responsible for the prototypic lichenoid tissue reaction or interface dermatitis disorder, lichen planus has recently been reviewed 61.

The subject of lichen planus (lichen planus) and dental metal allergy long has been debated. An overwhelming majority of the existing literature focuses on mercury and gold salts in relation to oral lichen planus. It is an intriguing revelation and subject of investigations 62. Accordingly, dental materials like mercury and gold and certain drugs may induce epithelial alterations, resembling oral lichen planus. Although, these alterations do not have all the clinical and/or the histological features of Olichen planus; yet these lesions are known as oral lichenoid lesions (OLLs). Onset and/or worsening of oral lichenoid lesions or oral lichen planus after the administration of anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy have been highlighted. Furthermore, development of symptomatic oral lichenoid lesions, in consequence to anti-HCV therapy (interferon-alpha and ribavirin), in two human immunodeficiency virus-HCV-coinfected subjects has also been described. An immunological cause related to coinfection and administration of different medications too could be responsible for the onset of oral lichenoid lesions. The new reports, together with the previous ones of a possible association between oral lichen planus and/or oral lichenoid lesions and anti-HCV therapy, highlight the absolute need to monitor carefully the human immunodeficiency virus-HCV-coinfected subjects who are about to start the anti-HCV therapy and to define better the clinical and histopathological criteria to distinguish oral lichen planus from oral lichenoid lesions 63.

It is intriguing at this point in time, to enlighten that fludarabine, a purine antimetabolite with potent immunosuppressive properties, has previously been associated with the development of transfusion-associated graft versus host disease (TA-GVHD) in patients with hematologic malignancies. Its role as a risk factor for transfusion-associated graft versus host disease in patients without underlying leukemia or lymphoma is uncertain.

However, the increasing use of these drugs in the treatment of autoimmune disease might result in occurrence of transfusion-associated graft versus host disease after fludarabine therapy. Such an episode-developing in-patient with systemic lupus erythematosus strongly suggests that this drug is sufficiently immunoablative to be an independent risk factor for transfusion-associated graft versus host disease 64. It is therefore, worthwhile to study this aspect in lichenoid interface dermatosis.

Table 2. Lichenoid dermatitis histopathological features

Lichenoid dermatitis treatment

Lichenoid dermatitis treatment involves treating the underlying cause. For example, for lichenoid drug eruption the trigger medication should be stopped and should result in improvement in the rash, although it can take weeks to months for it to disappear. Commonly flat pigmented freckles persist and fade more slowly. Nail disease will take six months or more to clear, although improvement can be seen gradually extending over this time. Sometimes the medication cannot be ceased because of the importance of the underlying medical condition compared to the rash, e.g. imatinib for chronic myeloid leukaemia or gastrointestinal stromal tumour. The dose may be reduced or continued unchanged and the rash treated with topical steroid cream or, if very extensive and severe, oral corticosteroids such as prednisone or prednisolone. Steroids may give good relief or even resolution.

References- Mutasim D. (2015) What Is Lichenoid Dermatitis?. In: Practical Skin Pathology. Springer, Cham. ISBN 978-3-319-14728-4 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14729-1_6

- Cohen PR. Injection Site Lichenoid Dermatitis Following Pneumococcal Vaccination: Report and Review of Cutaneous Conditions Occurring at Vaccination Sites. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6(2):287–298. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0105-x https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4906099

- Patrizi A, Di Lernia V, Ricci G, Masi M. Atopic background of a recurrent papular eruption of childhood (frictional lichenoid eruption) Pediatr Dermatol. 1990;7:111–5.

- Sardana K, Mahajan S, Sarkar R, Mendiratta V, Bhushan P, Koranne RV, et al. The spectrum of skin disease among Indian children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:6–13.

- Wüthrich B. Minimal Variants of Atopic Eczema. In: Ring J, Przybilla B, Ruzicka T, editors. Handbook of Atopic Eczema Second Edition. New York, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg; 2006. pp. 74–82.

- Williams HC, Burney PG, Hay RJ, Archer CB, Shipley MJ, Hunter JJ, et al. The UK Working Party’s Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis I: Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:383–96.

- Sardana K, Goel K, Garg VK, et al. Is frictional lichenoid dermatitis a minor variant of atopic dermatitis or a photodermatosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(1):66–73. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.147797 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4318066

- Pinkus H. Lichenoid tissue reactions. A speculative review of the clinical spectrum of epidermal basal cell damage with special reference to erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol 1973;107:840-6.

- Samman PD. Lichen planus and lichenoid eruptions. In: Rook A, Wilkinson DS, Ebling FJ, editors. Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1968. p. 1194-212.

- Hirsch P, Marmelzat WL. Lichenoid actinic keratosis. Deramtol Internationalis 1967;6:101-3.

- Lever WF. Histopathology of the skin. 4 th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co; 1967. pp. 255-6.

- El-Zawahari M. Lichen planus tropicus. Dermatol Internationalis 1965;4:92-5.

- Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Evolution, maturation, and regression of lesions of lichen planus. New observations and correlations of clinical and histologic findings. Am J Dermatopathol 1981;3:5-25

- Hartl C, Steen KH, Wegner H, Seifert HW, Bieber T. Unilateral linear lichen planus with mucous membrane involvement. Acta Derm Venereol 1999;79:145-6.

- Weedon D. The Lichenoid Reaction Pattern. In: Weedon D, editor. Skin Pathology. 2 nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. p. 31-74.

- Eisen D. The vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome of lichen planus. The clinical characteristics of 22 patients. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:1379-82.

- Vente C, Reich K, Rupprecht R, Neumann C. Erosive Mucosal lichen planus: Response to topical treatment with tacrolimus. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:338-42.

- Bettoli V, De Padova MP, Corazza M, Virgili A. Generalized lichen nitidus with oral and nail involvement in a child. Dermatology 1997;194:367-9.

- Hussain K. Summertime actinic lichenoid eruption a distinct entity, should be termed actinic lichen nitidus. Arch Dermatol 1998;134:1302-3.

- Khopkar U, Joshi R. Distinguishing lichen scrofulosorum from lichen nitidus. Dermatopathol: Pract Concept 1999;5:44-5.

- Ciconte A, Bekhor P. Lichen striatus following solarium exposure. Australas J Dermatol 2007;48:99-101.

- Rose C, Hauber K, Starostik P. Lichen striatus: A clinicopathologic study with follow-up in 13 patients. Am J Dermatopathol 2000;22:354.

- Herd RM, McLaren KM, Aldridge RD. Linear lichen planus and lichen striatus-opposite ends of a spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol 1993;18:335-7.

- Berger TG, Graham JH, Goette DK. Lichenoid benign keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11:635-8.

- Jang KA, Kim SH, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Lichenoid keratosis: A clinicopathologic study of 17 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:511-6.

- Sehgal VN. Twenty nail dystrophy trachyonychia: An overview. J Dermatol 2007;34:361-6.

- Wescsler HL. Dermatitis medicamentosa; a lichen-planus-like eruption due to quinidine. AMA Arch Dermatol Syphilol 1954;69:741-4.

- Hawk JL. Lichenoid drug eruption induced by propanolol. Clin Exp Dermatol 1980;5:93-96.

- West AJ, Berger TG, LeBoit PE. A comparative histopathologic study of photodistributed and nonphotodistributed lichenoid drug eruptions. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;23:689-93.

- Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Fixed Drug Eruption (FDE): Changing scenario of incriminating drugs. Int J Dermatol 2006;45:897-908.

- Solomon AR Jr. The histologic spectrum of the reactive inflammatory vesicular dermatoses. Dermatol Clin 1985;3:171-83.

- Stone N, Sheerin S, Burge S. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and graft vs. host disease: A clinical spectrum but a diagnostic dilemma. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:260-2.

- Rico MJ, Kory WP, Gould EW, Penneys NS. Interface dermatitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;16:1209-18.

- Saijo S, Honda M, Sasahara Y, Konno T, Tagami H. Columnar epidermal necrosis: A unique manifestation of transfusion-associated cutaneous graft-vs-host disease. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:743-6.

- Pittelkow MR, Daud MZ. Lichen Planus. In: Wolff K, Gold Smith LA, Katz SI, et al, editors. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in Genneral Medicine. 7 th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill Medical; 2008. p 244-55.

- Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Paraneoplastic pemphigus/paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome. Int J Dermatol 2009;48:162-9.

- Winkelmann RK. Spectrum of lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol 1979;6:457-62.

- Jacobs MI, Schned ES, Bystryn JC. Variability of the lupus band test. Results in 18 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol 1983;119:883-9.

- Tilly JJ, Drolat BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:606-24.

- Stefanato CM, Goldberg LJ, Andersen WK, Bhawan J. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome presenting as lichenoid dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol 2000;22:162-5.

- Nikkels AF, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Rentier B, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Low-productive alpha-herpesviridae infection in chronic lichenoid dermatoses. Dermatology 1998;196:442-6.

- Suarez J, Lopez B, Villaba R, Perera A. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: A case report and review of the literature. Dermatology 1996;192:277-9.

- Katoulis AC, Stavrianeas NG, Georgala S, Katsarou-Katsari A, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E, Antoniou C, et al. Familial cases of poikiloderma of civatte: Genetic implications in its pathogenesis? Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:385-7.

- Person JR, Bishop GF. Is poikiloderma a graft-versus-host-like reaction? Am J Dermatopathol 1984;6:71-2.

- Ito A, Funasaka Y, Shimoura A, Horikawa T, Ichihashi M. Dermatomyositis associated with diffuse dermal neutrophilia. Int J Dermatol 1995;34:797-8.

- Wang WJ. Clinical features of cutaneous amyloidoses. Clin Dermatol 1990;8:13-9.

- Horn TD, Redd JV, Karp JE, Beschorner WE, Burke PJ, Hood AF. Cutaneous eruptions of lymphocyte recovery. Arch Dermatol 1989;125:1512-7.

- Horn TD. Acute cutaneous eruptions after marrow ablation: Roses by other name? J Cutan Pathol 1994;21:385-92.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPD): An overview. Int J Dermatol 2004;43:482-8.

- Friedman SJ. Lichen spinulosus. Clinicopathologic review of thirty-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:261-4.

- Goeckerman WH, Montogomery H. Lupus eryhtematosus: An evaluation of histopathologic examination. Arch Dermatol 1932;25:304-16.

- Shiohara T, Moriya N, Nagashima M. The lichenoid tissue reaction. A new concept of pathogenesis. Int J Dermatol 1988;27:365-74.

- Iijima W, Ohtani H, Nakayama T, Sugawara Y, Sato E, Nagura H, et al. Infiltrating CD8+ T cells in oral lichen planus predominantly express CCR5 and CXCR3 and carry respective chemokine ligands RANTES/CCL5 and IP10/CXCL10 in their cytolytic granules: A potential self-recruiting mechanism. Am J Pathol 2003;163:261-8.

- Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus; a report of an international consensus meeting: Part 1. Viral infections and aetiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40-51.

- Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Zhao ZZ, Zhou XJ, Khan A, et al. The pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2002;13:350-65.

- Podack ER. Execution and suicide: Cytotoxic lymphocytes enforce draconian laws through separate molecular pathways. Curr Opin Immunol 1995:7:11-6.

- Shimizu M, Higaki Y, Higaki M, Kawashima M. The role of granzyme B-expressing CD8-positive T cells in apoptosis of keratinocytes in lichen planus. Arch Dermatol Res 1997;289:527-32.

- Prpiæ Massari L, Kastelan M, Gruber F, Laskarin G, Sotosek Tokmadziæ V, Strbo N, et al . Perforin expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes and skin-infiltrating cells in patients with lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:433-9.

- Mizukawa Y, Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: A prototypic disorder mediated by effector memory T cells. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2009;9:71-7.

- Bennion SD, Middleton MH, David-Bajar KM, Brice S, Norris DA. In three types of interface dermatitis, different patterns of expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-I (ICAM-I) indicate different triggers of disease. J Invest Dermatol 1995;105:71S-79S.

- Sontheimer RD. Lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis: Clinical and histological perspectives. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:1088-99.

- Scalf LA, Fowler JF Jr, Morgan KW, Looney SW. Dental metal allergy in patients with oral, cutaneous, and genital lichenoid reactions. Am J Contact Dermat 2001;12:146-50.

- Giuliani M, Lajolo C, Sartorio A, Scivetti M, Capodiferro S, Tumbarello M. Oral lichenoid lesions in HIV-HCV-coinfected subjects during antiviral therapy: 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:466-71.

- Leitman SF, Tisdale JF, Bolan CD, Popovsky MA, Klippel JH, Balow JE, et al. Transfusion-associated GVHD after fludarabine therapy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Transfusion 2003;43:1667-71.