What is LSD?

LSD is short for lysergic acid diethylamide (D-lysergic acid diethylamide), and is also known as acid, trips, tabs, microdots, dots, Lucy or “club drug”. LSD is an illicit hallucinogenic drug or psychedelic drug 1. It is illegal to administer, manufacture, buy, possess, process, or distribute LSD without a license from the DEA 2. LSD is a semisynthetic substance derived from lysergic acid, a natural substance from the parasitic rye fungus Claviceps purpurea 3. When people take LSD, it can powerfully distort their senses — they may see changing shapes or colors or have hallucinations. It can also intensify mood and alter thought processes. LSD produces an alteration of consciousness, increased sensory processing, produces changes in body perception, pseudo-hallucinations, thinking expansion, audiovisual synesthesia, altered meaning of perceptions, derealization, depersonalization, and mystical experiences 4, 5. People who use LSD have ‘trips’ or “mystical experiences”, which can be enjoyable or can be very frightening 6, 3.

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was first synthesized in 1937 by Albert Hoffman and its psychoactive effects discovered in 1943 7. LSD was used during the 1950s and 1960s as an experimental drug in psychiatric research for producing so‐called “experimental psychosis” by altering neurotransmitter system and in psychotherapeutic procedures (“psycholytic” and “psychedelic” therapy) 8. From the mid 1960s, LSD became an illegal drug of abuse with widespread recreational and spiritual purposes that continues today 9. Psychosis is when people lose some contact with reality. This might involve seeing or hearing things that other people cannot see or hear (hallucinations) and believing things that are not actually true (delusions).

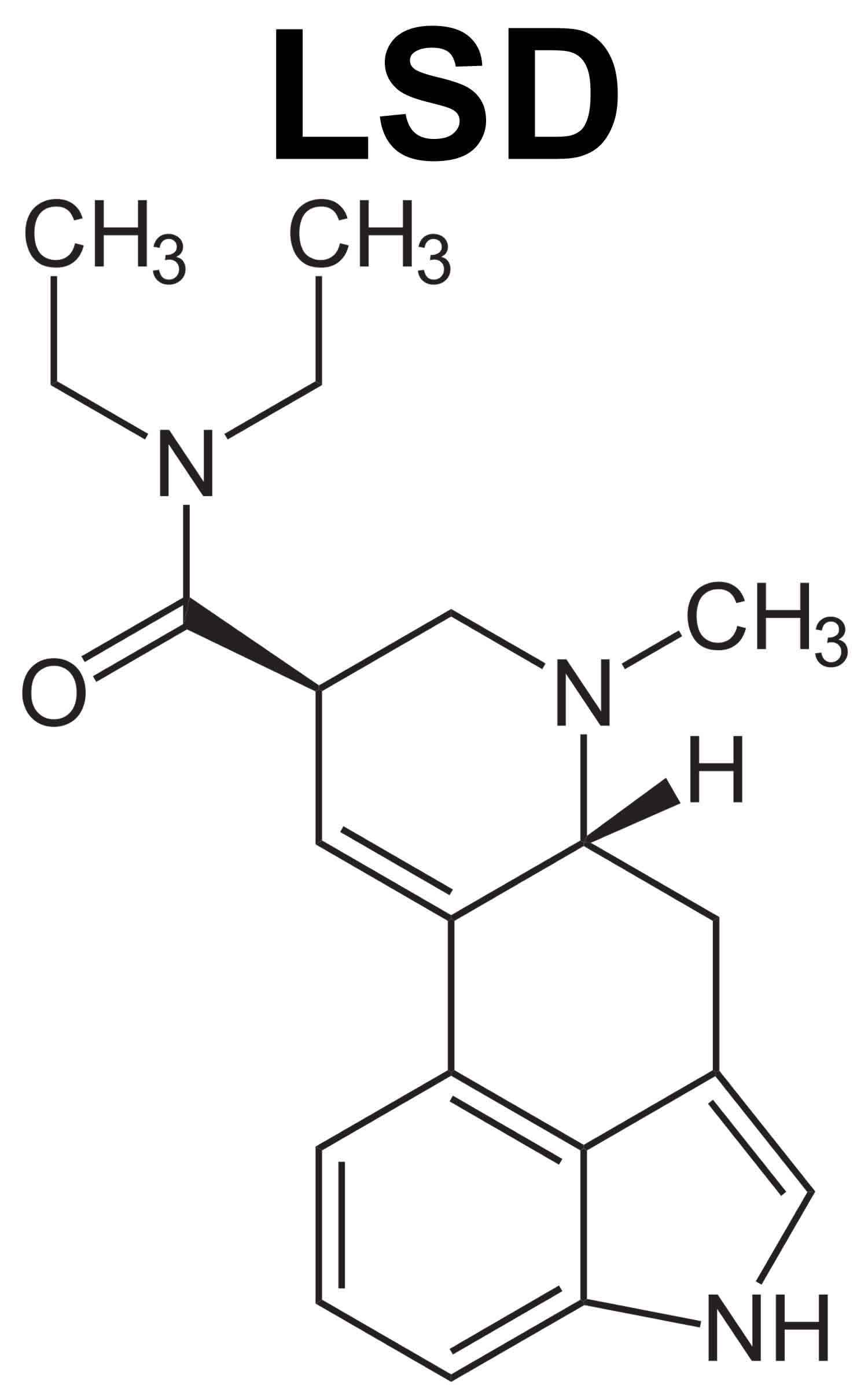

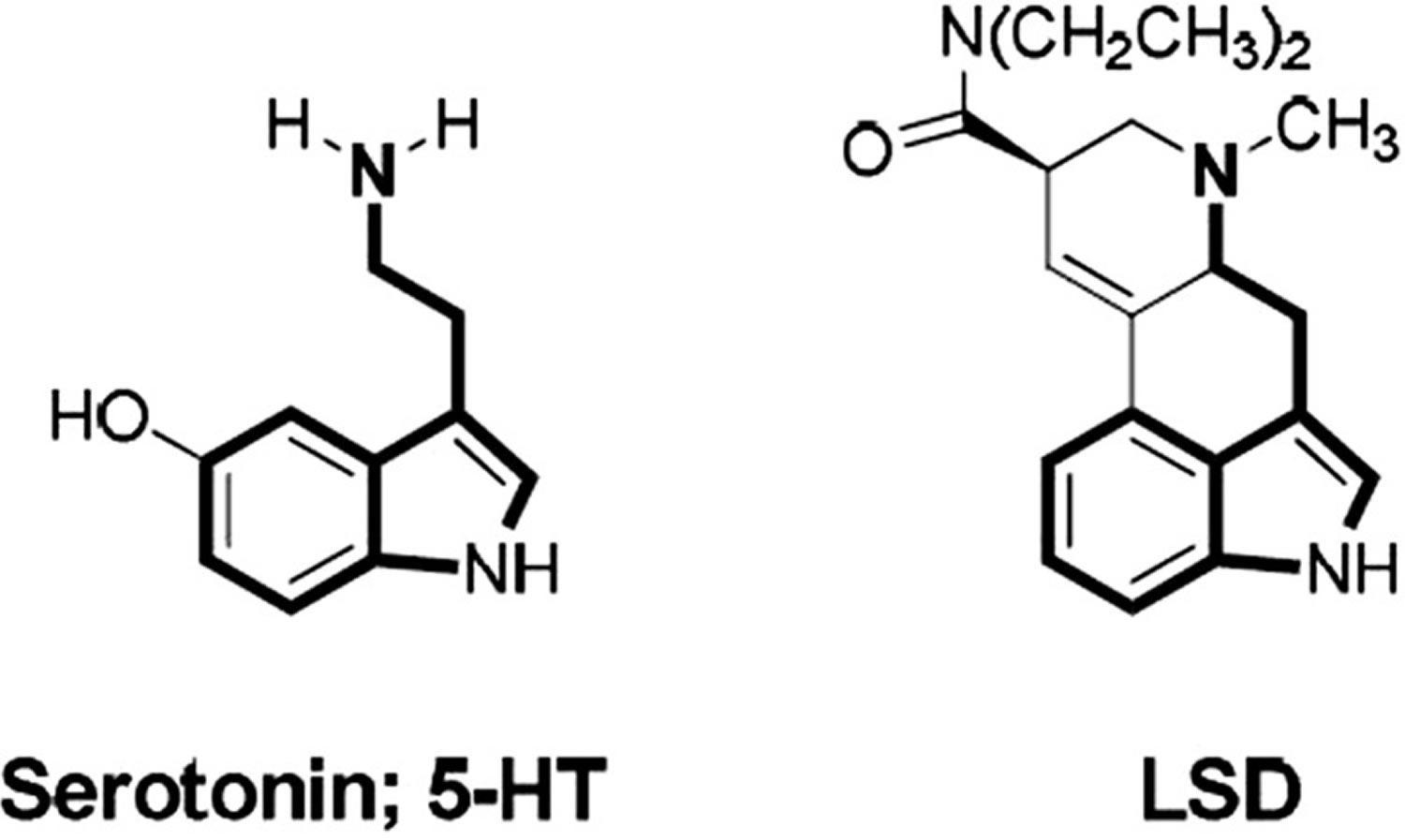

LSD is part of a family of drug group known as “classical hallucinogens” or “psychedelics” (term coined by Osmond in 1957) 10, sharing its chemical structure with magic mushrooms (psilocybin) and DMT (dimethyltryptamine) as a variant of indolamine (chemical structure similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin [also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT]) 11. Classical hallucinogens are psychoactive substances that are believed to mediate their effects mainly through an agonist activity in the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) 12. Experimental studies have previously shown that the use of serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A) antagonists attenuate the main effects of these substances, both in rats 13 and human subjects 14.

LSD is one of the most potent classical hallucinogens available, with the minimal recognizable dose of LSD in humans is about 25 mcg (microgram) orally 15. The “optimum” dosage for a typical fully unfolded LSD reaction is estimated to be in the range of 0.5 and 2 micrograms/kg body weight (100–150 mcg per dose) 16. The onset of effects usually begins within 30 to 60 minutes after taking the drug. The drug moves rapidly to the brain and is quickly distributed throughout the body, acting both on central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and autonomics. The drug disappears from the brain in 20 minutes, but the effects are prolonged and may last many more hours after it disappears from the brain. Its half-life is approximately 3 hours, varying between 2 and 5 hours, and its psychoactive effects are prolonged over time (up to 12 hours depending on the dose, tolerance, weight and age of the subject) 3. Recently LSD has been used in microdoses as low as 10 mcg to enhance performance 17. The subjective response between patients with similar concentrations of LSD and similar doses is unpredictable. Each patient may have a completely different experience.

More recent studies used 75 micrograms of LSD intravenously. Reported subjective effects began within 5 to 15 minutes. Effects peaked 45 to 90 minutes after intravenous dosing. The researchers reported no further details. In one study, the administration of 200 micrograms of LSD in a safe setting reportedly produced subjective positive effects for the user, further described as a long-lasting positive experience. There were significant reports of positive attitudes with self-esteem, mood, altruism, social skills, behavioral changes, and improved satisfaction in life. No reported negative changes in attitude, mood, social skills, or behavior were attributed to LSD 18.

LSD comes as an odorless white powder. The pure form of LSD is very strong, so it is usually diluted with other materials. The most common form is drops of LSD solution dried onto gelatin sheets, pieces of blotting paper (perforated sheets of paper often decorated with abstract artwork that can subdivide into smaller pieces with the substance uniformly laid across the sheet) or sugar cubes, which release the drug when they are swallowed. LSD is also sometimes sold as a liquid, small pills (microdot), in a tablet or in capsules.

LSD is usually swallowed or dissolved under the tongue, but it can be sniffed, injected, smoked or applied to the skin.

LSD can affect people differently based on:

- how much they take

- their height and weight

- their general health

- their mood

- their past experience with hallucinogens

- whether they use LSD on its own or with other drugs

- whether they use alone or with others, at home or at a party

LSD effects are extremely subjective, with significant variability and unpredictability. One patient may experience a positive effect filled with bright hallucinations, sights, and sensations, increased awareness owing to mind expansion, and marked euphoria. The positive spectrum of effects is colloquially called a “good trip.” Another patient may experience the total opposite with an experience filled with increased anxiety becoming panic, fear, depression, despair, and disappointment. The negative spectrum is colloquially called a “bad trip.” One patient can experience both the positive and negative spectrum at different times of use.

The short-term effects of LSD may include:

- seeing, smelling, hearing or touching things that aren’t real

- more intense senses

- a distorted sense of time and space

- strange feelings in the body, like floating

- rapidly changing or intense emotions

- altered state of thinking

- dilated pupils

- confusion

- headaches

- muscles twitching

- increased body temperature, heart rate and blood pressure

- insomnia, dizziness, nausea and vomiting

- being flushed, sweating or chills

The effects of LSD usually begin in 30 to 45 minutes and can last for 4 to 12 hours. The effects can last longer, depending on the dose taken.

In the days after using LSD, people may experience insomnia, fatigue, body and muscle aches or depression.

There are concerns about increased antisocial behavior and abuse with unsupervised use of LSD. There also are concerns about the negative implications of increased suggestibility. There are possible dangers of creating false memories or instilling wrong beliefs.

As a classic hallucinogen, LSD does not typically create compulsive drug-seeking behavior as is with most other drugs, but it can still be dangerous in non-clinical settings. Nonmedical use can precipitate prolonged psychiatric reactions in rare cases.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of serotonin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

[Source 12 ]What if I use other drugs or alcohol together with LSD?

The effects of taking LSD with other drugs (including those purchased over the counter or prescribed by your doctor) can be unpredictable and dangerous.

Using LSD with ice, speed or ecstasy increases the chance of a bad trip and can lead to a stroke.

Using LSD with alcohol may increase the chance of nausea and vomiting.

Can I become dependent on LSD?

LSD is not thought to cause physical dependence, but regular uses of LSD may experience a need or craving if they stop using the drug. However, this is not common.

Tolerance means that you must take more of the drug to feel the same effects you used to have with smaller amounts. Anyone can develop tolerance to LSD. Taking LSD for 3 or 4 consecutive days may lead to tolerance where no amount of the drug can produce the desired effects. After a short period of abstinence (3 to 4 days), normal tolerance returns.

How does LSD work?

The mechanism by which LSD works is mainly mediated by potently binding to human serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, dopamine D2, and alpha-2 (α2) adrenergic receptors and less potently to alpha-1 (α1) adrenergic, dopamine D1 and D3 receptors 19. LSD is a partial agonist at 5-HT2A receptors 19. 5-HT2A receptors primarily mediate the hallucinogenic effects of LSD 20. The affinity of hallucinogens for 5-HT2A receptors but not 5-HT1A receptors is correlated with psychoactive potency in humans. Although the subjective effects of LSD in humans can be blocked by pretreatment with a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist 21, the signaling pathways and downstream effects that mediate the effects of LSD have not been conclusively identified 12. One study suggests that LSD-induced 5-HT2A receptor activation leads to a breakdown of inhibitory processes in the hippocampal prefrontal cortex. Specifically, it has been demonstrated to reduce brain activity in the right middle temporal gyrus, superior/middle/inferior frontal gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex, and the left superior frontal and postcentral gyrus and cerebellum. Studies also have shown activation of the right hemisphere, altered thalamic functioning, and increased activity in the paralimbic structures and the frontal cortex; this all leads to the formation of induced visual imageries 22.

A key mechanism of action of LSD and other serotonergic hallucinogens is the activation of frontal cortex glutamate transmission secondary to 5-HT2A receptor stimulation. However, interactions between the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) and glutamate systems are unclear 12. Increases in glutamatergic activity in the prefrontal cortex may result in downstream modulatory effects in subcortical areas and alterations in the gating functions of sensory and cognitive processing 5. Some notable differences can be seen between the pharmacological profiles of LSD and other serotonergic hallucinogens. First, LSD more potently binds 5-HT2A receptors than psilocybin, mescaline, and DMT (Table 1) 19. Second, LSD is more potent at 5-HT1 receptors 19, which may contribute to the effects of hallucinogens. However, there are no studies on the role of the 5-HT1 receptor in the effects of LSD in humans 5. Third, LSD binds adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors at submicromolar concentrations, which is not the case for other classic serotonergic hallucinogens (Table 1) 19. In animals, dopamine D2 receptors were shown to contribute to the discriminative stimulus effects of LSD in the late phase of the acute response 23. In humans, LSD may indirectly enhance dopamine neurotransmission 12, with no role of direct dopamine D2 receptor stimulation 20. Serotonergic hallucinogens presumably produce overall similar acute subjective and potential therapeutic effects in humans 24. The early clinical trials used mostly LSD while most of the recent hallucinogen studies used psilocybin because of its ease of use due to the shorter action and less controversial history 25. However, modern studies need to directly investigate whether the effects of LSD in humans differ qualitatively from those of psilocybin and DMT, notwithstanding LSD’s longer duration of action.

In substance abuse, it is well established that anxiety and stress are important triggers for relapse. It is possible that 5-HT2A receptor downregulation by hallucinogens could help in stress-induced relapses. LSD may also affect the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor(GDNF). Both of these play critical roles in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. There is some evidence that LSD can induce neuroplastic changes suggesting a basis for the persistent behavioral changes. LSD also induces remodeling of pyramidal cell dendrites.

Repeated administration of psychedelics leads to a very rapid development of tolerance known as tachyphylaxis, a phenomenon believed to result from 5-HT2A receptor downregulation. Several studies have shown that rapid tolerance to psychedelics correlates with downregulation of 5-HT2A receptors. For example, daily LSD administration selectively decreased 5-HT2 receptor density in the rat brain 26. Daily administration of LSD leads essentially to complete loss of sensitivity to the effects of the drug by day 4 27. In humans, cross-tolerance occurs between mescaline and LSD 28 and between psilocybin and LSD 29.

Table 1 shows the human receptor interaction profile for LSD compared with that of other classic serotonergic hallucinogens obtained with the same assays.

Table 1. Receptor interaction profiles for LSD and other classic serotonergic hallucinogens at human receptors

| LSD a | Psilocin b | DMT b | Mescaline a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.003±0.0005 | 0.123±0.02 | 0.075±0.02 | 4.6±0.4 |

| 5-HT2A | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.004±0.001 | 0.049±0.01 | 0.237±0.04 | 6.3±1.8 |

| 5-HT2A | Activation potency EC50±SD (μM) | 0.261±0.15 | 0.721±0.55 | 0.076±0.03 | 10±1.8 |

| 5-HT2A | Activation efficacy % maximum±SD | 28±10 | 16±8 | 40±11 | 56±15 |

| 5-HT2B | Activation potency EC50±SD (μM) | 12±0.4 | >20 | 3.4±3.2 | >20 |

| 5-HT2B | Activation efficacy % maximum±SD | 71±31 | 19±6 | ||

| 5-HT2C | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.015±0.003 | 0.094±0.009 | 0.424±0.15 | 17±2.0 |

| α2A | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.67±0.18 | 6.7±1.1 | 1.3±0.2 | >15 |

| α1A | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.012±0.002 | 2.1±0.01 | 2.1±0.4 | 1.4±0.2 |

| D1 | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.31±0.09 | >14 | 6.0±0.9 | >14 |

| D2 | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.025±0.0004 | 3.7±0.6 | 3.0±0.4 | >10 |

| D3 | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 0.10±0.01 | 8.9±0.8 | 6.3±2.1 | >17 |

| H1 | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | 1.1±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 | 0.22±0.03 | >25 |

| TAAR1 c | Activation potency EC50±SD (μM) | >20 | >30 | >10 | >10 |

| NET | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | >30 | 13±1.7 | 6.5±1.3 | >30 |

| NET | Inhibition potency IC50 (μM) (95% CI) | >100 | 14 (10–19) | 3.9 (2.8–5.3) | >100 |

| DAT | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | >30 | >30 | 22±3.9 | >30 |

| DAT | Inhibition potency IC50 (μM) (95% CI) | >100 | >100 | 52 (37–72) | >100 |

| SERT | Receptor binding Ki±SD (μM) | >30 | 6.0±0.3 | 6.0±0.6 | >30 |

| SERT | Inhibition potency IC50 (μM) (95% CI) | >100 | 3.9 (3.1–4.8) | 3.1 (2.4–4.0) | >100 |

| Dose d | milligram (mg) | 0.1 | 12 | 40 | 300 |

Footnotes: All data were generated using the same assays across substances to allow for direct comparisons.

a Rickli et al, 2015 30

b Rickli et al, 2016 19

c LSD activates rat and mouse trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) but not human TAAR1 31.

d Estimated average psychoactive dose in humans from Passie et al, 2008 32 and Nichols, 2004 33

Abbreviations: DAT = dopamine transporter; NET = norepinephrine transporter; SERT = serotonin transporter.

[Source 5 ]LSD interactions with other substances

Various studies have evaluated drug–drug interactions with LSD. Early clinical studies focussed primarily on LSD interactions with neuroleptics, especially chlorpromazine 34. Chlorpromazine has proven to be an incomplete antagonist of LSD. When chlorpromazine is given simultaneously with LSD to humans in small doses (below 0.4 mg/kg), it produces no changes in LSD’s effects 34. At higher doses (0.7 mg/kg) of chlorpromazine, LSD‐induced side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, reduction in motor activity, and/or anxiety, have been reported to diminish or disappear 35. Chlorpromazine did not appreciably alter the production of hallucinations or delusions, but associated unpleasant feelings were reduced or eliminated 36.

Sedative‐hypnotics like diazepam (5mg p.o./i.m.) are often used in the emergency room setting for acute presentations of LSD intoxication to help reduce panic and anxiety 37. Chronic administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as well as monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) antidepressants are reported to diminish LSD effects 38. An explanation may be that chronic application of antidepressants decrease 5‐HT2‐receptor expression in several brain regions 39. In turn, one could predict that reabsorption of 5‐HT2A receptors will not be complete after single predosing with an SSRI or MAOIs; in such circumstances, the risk for serotonin syndrome may be heightened. Lithium and some tricyclic antidepressants have also been reported to increase the effects of LSD 38. It has to be mentioned that LSD in combination with lithium drastically increases LSD reactions and can lead to temporary comatose states as suggested by anecdotal medical reports 3.

LSD uses

Currently there is no approved uses for LSD-assisted therapy 1. LSD was used as a pharmacological model of psychosis in preclinical research. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was studied from the 1950s to the 1970s to evaluate behavioral and personality changes, as well as remission of psychiatric symptoms in various disorders. From 1949 to 1966, LSD (Delysid© Sandoz, LSD 25) was provided to psychiatrists and researchers ‘to gain insights into the world of mental patients’ and to assist psychotherapy. LSD has been used in the past for non-FDA approved treatments of anxiety, depressive disorders including those with conversion phobia, neurosis, manic-depression, and reactive depression, cyclothymic (obsessional) and passive-aggressive (obsessional) compulsive sexual deviation addiction, psychosomatic disorders, mixed, pan-neuroticism (including schizophrenia), borderline or latent and personality disorders (especially transient situational). The threshold dose of LSD is commonly accepted to be 15 micrograms (mcg), while a relatively heavy dose at the opposite end of the accepted spectrum is around 300 micrograms. As the dosage increases beyond this arbitrary setpoint, reports suggest an increase in the intensity of the drug’s effects 40.

LSD possession became illegal in the United States on October 24, 1968, in an amendment of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. LSD currently sits on a shortlist of schedule 1 drugs, along with other hallucinogens and stimulants such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT), gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), heroin, marijuana, methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), mescaline, and psilocybin 40. Because of the controversy surrounding LSD, clinical trials have been difficult to organize.

LSD as a treatment

Psychedelic drugs can affect the function and structure of the brain and promote neuron growth 41. Exactly how LSD affects the brain is complicated, but it seems to interact with multiple receptors and chemicals, such as serotonin and dopamine 42.

Research is exploring the use of LSD in developing new ways of thinking and ‘resetting’ the brain’s habitual patterns of thought.

The renewed interest in LSD is building on studies conducted 40 years ago primarily focusing on treating 5:

- Depression

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Drug dependency

- Reducing anxiety in patients with a life-threatening disease 43, 44.

- A larger trial that uses LSD in patients who suffer from anxiety associated with severe somatic disease and anxiety disorder is conducted in Switzerland 45.

LSD-assisted therapy has been shown to enhance suggestibility without hypnotic induction. It has shown the most improvement in suggestibility in neurotic and schizophrenic patients but the least in depression 1. Neural plasticity in the cortex and cognitive flexibility are possibly necessary for demonstrable improvement in suggestibility.

Research has also begun to look at LSD as a possible treatment for Alzheimer dementia and as a last resort for migraines or cluster headaches 1. This role is partly because patients have self-medicated using LSD off-label as an ablative therapy for treatment-resistant migraines and cluster headaches. Patients obtained the illicit psychoactive substances as a last resort. When patients use LSD as a treatment or a recreational drug, there are few if any reports of psychoactive effects. The effects were reportedly tolerable or avoided using minimal doses.

Researchers continue to study the utility of LSD-assisted therapy. The following non-FDA-approved indications show the most evidence for serotonin-based psychoactive agents: substance use disorders, especially in treating chronic alcohol addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in patients suffering from life-threatening illnesses. Combining LSD with counseling, researchers were able to create a psychedelic “trip” for the terminally ill, thereby decreasing the anxiety refractory to conventional anxiolytic therapy, depression, and pain associated with life-threatening diseases such as cancer. Sleep reportedly improved with terminally ill patients, and they were less preoccupied with death.

The role of LSD in improving mental health is linked to a weakening or ‘dissolution’ of the ego, helping individuals see the ‘bigger picture’ beyond their personal problems 43.

For therapeutic treatment, LSD is administered under supervision in a safe environment, such as a psychologist’s office. The psychologist or medical professional provides guidance and reassurance as the patient experiences the effects of the drug. Although the patient’s consciousness is dramatically altered, they still have a clear memory of their experience 43.

While LSD doesn’t seem to pose a risk for dependency and no overdose deaths have been reported, some people do experience anxiety and confusion. There have also been rare cases of self-harm outside of a therapeutic context 46.

People can have powerfully confronting experiences under the influence of LSD which is why administering it in a controlled environment where the participant is informed, supported and monitored, is important 47.

LSD therapy trials

While there’s positive progress in LSD-assisted therapy, research into its potential therapeutic benefits has a long way to go before scientists can really understand LSD’s impact on the brain. A 2016 study 48 demonstrated that LSD has the potential to change established patterns of thought and again flagged its potential as a treatment for depression and anxiety. Participants without a history of mental illness were given a single dose of LSD (75 mcg, intravenously), which resulted in feelings of openness, optimism, and mood for around two weeks.

In another study by Schmid et al. 49, LSD (200 mcg) was administered orally to 16 healthy subjects in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. LSD produced a pronounced alteration in waking consciousness that lasted for 12 hours and included visual hallucinations, audio-visual synesthesia, and positively experienced derealization and depersonalization phenomena. Compared with placebo, LSD increased subjective well-being, happiness, closeness to others, openness, and trust 49. Increases in blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, pupil size, plasma cortisol, prolactin, oxytocin, and epinephrine also were measured. On the five-dimensional altered states of consciousness (5D-ASC) scale, LSD produced higher scores than did psilocybin or DMT. The authors also described subjective effects on mood that were similar to those reported for MDMA that might be useful in psychotherapy. No severe acute adverse effects were observed and the effects subsided completely within 72 hours 49.

Research on LSD as a therapeutic treatment for alcohol dependency has demonstrated similar results with individuals experiencing improved levels of optimism and positivity, as well as an increased capacity to face their problems 47.

One of the more promising trials was with patients facing a life-threating disease. LSD was found to reduce anxiety associated with the anticipation of death 44. Patients also demonstrated an improved sense of self-assurance, relaxation, and mental strength, with the results lasting around 12 months 43.

LSD therapy the unknowns

In contrast with existing therapies for depression and some other mental health conditions, which may take years to create change, the results of LSD-assisted therapy seem to have a positive impact quite quickly.

One question that remains is how often the LSD-assisted therapy should be re-visited to maintain an individual’s progress 50. The viability of LSD as a treatment for people living with several other mental health conditions remains unknown.

As research continues to explore the full impact and medical potential of this drug, it’s clear that LSD offers a fascinating look into the human mind, and the need to look beyond the often sensationalist headlines when assessing any drug.

LSD side effects

LSD is physically non-toxic, but there are psychological risks especially when it is used in unsupervised settings 5. In addition, it is important to note that many novel hallucinogens are being used and may even be sold as LSD but have a different pharmacology and possibly risk profile than LSD 30. LSD has typically been reported to produce flashbacks. “Flashbacks” are characterized in the WHO International Classification of Diseases, Version 10 (ICD‐10) as of an episodic nature with a very short duration (seconds or minutes) and by their replication of elements of previous drug‐related experiences 51. In a web-based survey among hallucinogen users, greater past LSD use was a predictor of the probability of experiencing unusual substance-free visual experiences 52. These reexperiences of previous drug experiences occur mainly following intense negative experiences with hallucinogens, but can sometimes also be self‐induced by will for positive reexperiences and are in this case sometimes referred to as “free trips” 51. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Version IV (DSM‐IV) defines clinically significant flashbacks as “Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder”(HPPD), which appears to be particularly associated with LSD 53.

The term hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) has displaced an earlier somewhat more nonspecific one known as “flashbacks,” which was a re-experiencing of one or more of the perceptual effects induced by a hallucinogen at some later time, after the acute drug effects had worn off. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is composed of afterimages, perception of movement in peripheral visual fields, blurring of small patterns, halo effects, and macro- and micropsia long after the drug has been used 53. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is a diagnosis defined in DSM-5 as a disorder in which patients not currently intoxicated by a hallucinogenic agent experience perceptual symptoms that first manifested during prior hallucinogenic experiences. These symptoms must result in clinically significant distress and impair normal social and occupational functions. Reports have shown these symptoms to include mainly visual disturbances, such as geometric hallucinations, halos surrounding objects, alterations in motion-perception, floaters, and flashbacks to images seen during the prior drug experience 54.

Halpern and Pope 55 reviewed 20 quantitative studies from 1955 to 2001 and concluded that the occurrence of HPPD is very rare, but, when it occurs, it typically will have a limited course of months to a year, but can, in some even rarer cases, last for years with considerable morbidity. They also noted that when LSD was used in a therapeutic or research setting, HPPD appeared less frequently than when LSD was used recreationally 53. The authors concluded, however, that some individuals, especially users of LSD, can experience a long-lasting HPPD syndrome with symptoms of “persistent perceptual abnormalities reminiscent of acute intoxication.” Nevertheless, the incidence of HPPD is very small given the many tens of millions of persons who have taken LSD, most often in a recreational setting. Litjens et al. 56 provided a recent comprehensive review on the subject of HPPD. The actual incidence of HPPD is not known and depends on the prevalence of use in different countries, but epidemiologic information is scarce 57.

Although very rare, there have been reports of rhabdomyolysis after ingestion of LSD 58. Raval et al. 59 reported on a 19-year-old woman who experienced severe lower-extremity ischemia related to a single use of LSD 3 days prior to presentation. After intra-arterial nitroglycerin and verapamil failed, balloon percutaneous transluminal angioplasty therapy led to rapid clinical improvement in lower-extremity perfusion. As of the date of the report, the patient had not required a major amputation.

Sunness 60 described a 15-year-old female patient with a 2-year history of afterimages and photophobia after a history of drug use that included LSD, marijuana, and other illicit drugs. She had discontinued LSD 1 year prior to examination. Although the author connected her visual problems with her prior LSD use, it is not at all clear from the report that her LSD use was the cause of her visual problem.

Bernhard and Ulrich 61 reported a case of cortical blindness in a 15-year-old girl. She had headache and nausea 5 days after taking LSD and suddenly developed complete blindness in both eyes. The blindness persisted for 48 hours. Over the next 3 months, the subject had three more episodes of complete blindness that lasted 12–36 hours, with no visual disturbances between episodes. The authors suggested that the temporary blindness might be a correlate of “flashbacks” caused by LSD 61.

LSD use may cause:

- Hallucinations

- Greatly reduced perception of reality, for example, interpreting input from one of your senses as another, such as hearing colors

- Impulsive behavior

- Rapid shifts in emotions

- Permanent mental changes in perception

- Rapid heart rate and high blood pressure

- Tremors

- Flashbacks, a re-experience of the hallucinations — even years later

The most common unpleasant reaction from taking LSD is an episode of anxiety or panic (with severe, terrifying thoughts and feelings, fear of losing control, fear of insanity or death, and despair), commonly known as “bad trip” and is common when using LSD for the first time 62.

If you have a “bad trip”, you might experience:

- Extreme anxiety or fear

- Frightening hallucinations (e.g. spiders crawling on the skin)

- Panic, making you take risks (like running into the traffic or jumping off a balcony)

- Feeling you are losing control or going mad

- Paranoia (feeling that other people want to harm you)

Very rarely, someone experiencing a bad trip may attempt suicide or become violent. If someone you know is having a bad trip, they need to be reassured and comforted until the effects of the drug wear off. This can take many hours. They may not get over a bad trip for several days.

If you can’t wake someone up, they are having abdominal pain, seizures, they are overheated, or are paranoid and you can’t calm them down, or you are concerned the drugs may have made them fall and they have injured their head — call an ambulance immediately.

Other complicated reactions may include temporary paranoid ideation and, as after‐effects in the days following a LSD experience, temporary depressive mood swings and/or increase of psychic instability 63.

LSD particularly among vulnerable people and at high dose may also rarely induce lasting psychosis 4. Psychosis is when people lose some contact with reality. This might involve seeing or hearing things that other people cannot see or hear (hallucinations) and believing things that are not actually true (delusions).

The 2 main symptoms of psychosis are:

- Hallucinations – where a person hears, sees and, in some cases, feels, smells or tastes things that do not exist outside their mind but can feel very real to the person affected by them; a common hallucination is hearing voices

- Delusions – where a person has strong beliefs that are not shared by others; a common delusion is someone believing there’s a conspiracy to harm them

The combination of hallucinations and delusional thinking can cause severe distress and a change in behaviour.

Experiencing the symptoms of psychosis is often referred to as having a psychotic episode.

You should see your doctor or a mental health specialist immediately if you’re experiencing symptoms of psychosis. It’s important psychosis is treated as soon as possible, as early treatment can be more effective.

Crucially, there is a lack of evidence that other complications will routinely occur or persist in healthy persons taking LSD in a familiar surrounding. Cohen 64, Malleson 65 and Gasser 66 observed approximately 10,000 patients safely treated with LSD as a psycholytic agent. Past clinical studies with LSD were completed reporting very few if any complications 3 .

An extensive number of individuals participated in LSD research, with Passie 8 estimating some 10,000 patients participating in research of the 1950s and 1960s. The incidence of psychotic reactions, suicide attempts, and suicides during treatment with LSD, appears comparable to the rate of complications during conventional psychotherapy.

Mental effects

The mental effects of LSD are the most pronounced, but they are unpredictable. They occur because of the interruption of the normal interaction between the brain cells and serotonin.

- Delusions

- Visual hallucinations

- A distorted sense of time and identity

- An impaired depth and time perception

- Artificial euphoria and certainty

- A distorted perception of objects, movements, colors, sounds, touch, and the user’s body image

- Severe, terrifying thoughts and feelings

- Fear of losing control

- Fear of death

- Panic attacks

Visual effects

Visual changes are very common. Patients can become fixated on the intensity of specific colors. Sensations can also have a cross-over phenomenon. Patients who use LSD can reportedly have feelings of “hearing colors” and “seeing sounds.”

Behavioral and emotional effects

Behavioral and emotional dangers are very noticeable. Severe anxiety, paranoia, and panic attacks often occur at high doses. These are colloquially called “bad trips.” Usually, these bad experiences are attributed by users to the environment and people surrounding their use at the time. Extreme changes in mood from a “spaced-out bliss” to “intense terror” can occur. The changes can be frightening, triggering panic attacks. Some people never recover from these bizarre psychoses.

LSD demonstrably produces these emotions:

- Feelings of happiness

- Trust of and closeness to others

- Enhanced explicit and implicit emotional empathy

- Impaired recognition of sad and fearful faces

LSD-enhanced participants desired to be with other people and increased their prosocial behavior; this is theoretically due to the increased plasma oxytocin levels that appear to contribute to the empathogenic prosocial effects.

Physical effects

The physical effects of LSD occur via the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. Patients commonly have the following physical symptoms:

- Dilated pupils

- Higher or lower body temperature

- Sweating or chills

- Loss of appetite

- Sleeplessness

- Dry mouth

- Tremors

LSD use can lead to hypothermia, piloerection, tachycardia with palpitation, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia.

The autonomic reactions listed above are not as significant as the mental and behavioral effects of LSD on the body. Actions on the motor and the central nervous system can lead to increased activity of the monosynaptic reflexes, an increase in muscle tension, tremors, and muscular incoordination.

LSD toxicity

There have been no documented human deaths from an LSD overdose 67, 3. Eight individuals who accidentally consumed a very high dose of LSD intranasally (mistaking it for cocaine) had plasma levels of 1000–7000 mcg per 100 mL blood plasma and suffered from comatose states, hyperthermia, vomiting, light gastric bleeding, and respiratory problems. However, all survived with hospital treatment and without residual effects 68.

Treatment of LSD toxicity is mainly supportive. Autonomic symptoms require symptomatic treatment. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) published protocols for improving treatment for patients under the influence of or withdrawing from specific substances in a 2006 update. For hallucinogenic toxicity, the recommendation is to provide a quiet environment for the patient, preferably free from external stimuli, and to provide direct one-to-one supervision to ensure the patient does not cause any harm, whether it is self-harm or harm to others. The guidelines also state that a low dose of a benzodiazepine may be indicated in some cases for control of anxiety. Individuals who have taken large doses of LSD are at risk for residual psychotic symptoms and are therefore managed with antipsychotic drugs if symptoms manifest and persist 69.

In 1967, a report gave evidence for LSD‐induced chromosomal damage 70. This report could not stand up to meticulous scientific examination and was disproved by later studies 71, 72. Empirical studies showed no evidence of teratogenic or mutagenic effects from use of LSD in man 73, 74. Teratogenic effects in animals (mice, rats, and hamsters) were found only with extraordinarily high doses (up to 500 mcg/kg s.c.) 75. The most vulnerable period in mice was the first 7 days of pregnancy 76. LSD has no carcinogenic potential 71.

Autonomic side effects

The threshold dose for measurable sympathomimetic effects in humans is 0.5–1.0 mcg/kg LSD orally 77. A moderate dose of LSD for humans is estimated as 75–150 mcg LSD orally 71. LSD moderately increased blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and pupil size 78. The sympathomimetic effects of 100 and 200 mcg doses of LSD were similar 79 and less pronounced than those of MDMA (ecstasy) and stimulants 80. Acute adverse effects up to 10–24 hour after LSD administration included difficulty concentrating, headache, dizziness, lack of appetite, dry mouth, nausea, imbalance, and feeling exhausted. Headaches and exhaustion may last up to 72 hours 49.

Endocrine side effects

LSD acutely increased plasma concentrations of cortisol 81, prolactin, oxytocin, and epinephrine (adrenaline) 49. LSD does not increase plasma concentrations of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) 49, testosterone, or progesterone 81. The endocrine effects of LSD are consistent with those of other serotonergic substances including psilocybin, DMT (dimethyltrytamine) and MDMA 82.

Long-term problems

It is possible to experience flashbacks weeks, months or years after taking LSD. Flashbacks are when you feel the effects of the drug again, like having hallucinations, for a minute or 2. They are more common in people who use LSD regularly.

Using LSD can damage the memory and concentration. LSD may also trigger or worsen mental health problems like depression, anxiety and schizophrenia.

References- Hwang KAJ, Saadabadi A. Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) [Updated 2021 Aug 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482407

- Belouin SJ, Henningfield JE. Psychedelics: Where we are now, why we got here, what we must do. Neuropharmacology. 2018 Nov;142:7-19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.02.018

- Passie, T., Halpern, J. H., Stichtenoth, D. O., Emrich, H. M., & Hintzen, A. (2008). The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 14(4), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x

- De Gregorio, D., Comai, S., Posa, L., & Gobbi, G. (2016). d-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) as a Model of Psychosis: Mechanism of Action and Pharmacology. International journal of molecular sciences, 17(11), 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17111953

- Liechti M. E. (2017). Modern Clinical Research on LSD. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(11), 2114–2127. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.86

- Pahnke WN, Richards WA. Implications of LSD and experimental mysticism. J Relig Health. 1966 Jul;5(3):175-208. doi: 10.1007/BF01532646

- Hofmann A. How LSD originated. J Psychedelic Drugs. 1979 Jan-Jun;11(1-2):53-60. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1979.10472092

- Passie T. Psycholytic and psychedelic therapy research: A complete international bibliography 1931–1995. Hannover : Laurentius Publishers, 1997.

- Krebs, T. S., & Johansen, P. Ø. (2013). Over 30 million psychedelic users in the United States. F1000Research, 2, 98. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-98.v1

- OSMOND H. A review of the clinical effects of psychotomimetic agents. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1957 Mar 14;66(3):418-34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb40738.x

- Hill SL, Thomas SH. Clinical toxicology of newer recreational drugs. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011 Oct;49(8):705-19. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.615318. Erratum in: Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011 Nov;49(9):880.

- Nichols D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews, 68(2), 264–355. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

- Glennon RA, Titeler M, McKenney JD. Evidence for 5-HT2 involvement in the mechanism of action of hallucinogenic agents. Life Sci. 1984 Dec 17;35(25):2505-11. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90436-3

- Valle M, Maqueda AE, Rabella M, Rodríguez-Pujadas A, Antonijoan RM, Romero S, Alonso JF, Mañanas MÀ, Barker S, Friedlander P, Feilding A, Riba J. Inhibition of alpha oscillations through serotonin-2A receptor activation underlies the visual effects of ayahuasca in humans. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 Jul;26(7):1161-75. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.03.012

- Hoffer A. LSD: A review of its present status. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1965;6:183–255. doi: 10.1002/cpt196562183

- Fuentes, J. J., Fonseca, F., Elices, M., Farré, M., & Torrens, M. (2020). Therapeutic Use of LSD in Psychiatry: A Systematic Review of Randomized-Controlled Clinical Trials. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00943

- Hutten, N., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., & Kuypers, K. (2019). Motives and Side-Effects of Microdosing With Psychedelics Among Users. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 22(7), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyz029

- Lipari RN, Ahrnsbrak RD, Pemberton MR, et al. Risk and Protective Factors and Estimates of Substance Use Initiation: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2017 Sep. In: CBHSQ Data Review. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2012-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481723

- Rickli A, Moning OD, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive tryptamines compared with classic hallucinogens. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 Aug;26(8):1327-37. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.05.001

- Kraehenmann R, Pokorny D, Vollenweider L, Preller KH, Pokorny T, Seifritz E, Vollenweider FX. Dreamlike effects of LSD on waking imagery in humans depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017 Jul;234(13):2031-2046. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4610-0

- Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, Planzer A, Kraehenmann R, Stämpfli P, Liechti ME, Seifritz E, Vollenweider FX. The Fabric of Meaning and Subjective Effects in LSD-Induced States Depend on Serotonin 2A Receptor Activation. Curr Biol. 2017 Feb 6;27(3):451-457. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.030

- Jalal B. (2018). The neuropharmacology of sleep paralysis hallucinations: serotonin 2A activation and a novel therapeutic drug. Psychopharmacology, 235(11), 3083–3091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5042-1

- Marona-Lewicka D, Nichols DE. Further evidence that the delayed temporal dopaminergic effects of LSD are mediated by a mechanism different than the first temporal phase of action. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007 Oct;87(4):453-61. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.06.001

- HOLLISTER LE, HARTMAN AM. Mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide and psilocybin comparison of clinical syndromes, effects on color perception and biochemical measures. Compr Psychiatry. 1962 Aug;3:235-42. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(62)80024-8

- Nichols DE, Johnson MW, Nichols CD. Psychedelics as Medicines: An Emerging New Paradigm. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Feb;101(2):209-219. doi: 10.1002/cpt.557

- Buckholtz NS, Zhou DF, Freedman DX, Potter WZ. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) administration selectively downregulates serotonin2 receptors in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990 Apr;3(2):137-48.

- BELLEVILLE RE, FRASER HF, ISBELL H, LOGAN CR, WIKLER A. Studies on lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25). I. Effects in former morphine addicts and development of tolerance during chronic intoxication. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1956 Nov;76(5):468-78.

- BALESTRIERI A, FONTANARI D. Acquired and crossed tolerance to mescaline, LSD-25, and BOL-148. AMA Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1959 Sep;1:279-82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1959.03590030063008

- ISBELL H, WOLBACH AB, WIKLER A, MINER EJ. Cross tolerance between LSD and psilocybin. Psychopharmacologia. 1961;2:147-59. doi: 10.1007/BF00407974

- Rickli A, Luethi D, Reinisch J, Buchy D, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel N-2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe) derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxy-substituted phenethylamines (2C drugs). Neuropharmacology. 2015 Dec;99:546-53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.034

- Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016 Apr;357(1):134-44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229765

- Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, Hintzen A. The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008 Winter;14(4):295-314. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x

- Nichols DE. Hallucinogens. Pharmacol Ther. 2004 Feb;101(2):131-81. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002

- MURPHREE HB. Quantitative studies in humans on the antagonism of lysergic acid diethylamide by chlorpromazine and phenoxybenzamine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1962 May-Jun;3:314-20. doi: 10.1002/cpt196233314

- HOCH PH. Experimental psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 1955 Apr;111(10):787-90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.111.10.787

- GIBERTI F, GREGORETTI L. Prime esperienze di antagonismo psicofarmacologico; psicosi sperimentale da LSD e trattamento con cloropromazina e reserpina [First trials of psychopharmacological antagonism; experimental psychoses induced with d-lysergic acid diethylamide and treated with chlorpromazine and reserpine]. Sist Nerv. 1955 Jul-Aug;7(4):301-10. Italian.

- Levy RM. Diazepam for L.S.D. intoxication. Lancet. 1971 Jun 19;1(7712):1297. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91810-1

- Bonson KR, Murphy DL. Alterations in responses to LSD in humans associated with chronic administration of tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors or lithium. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73(1-2):229-33. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00102-7

- Heninger GR, Charney DS. Mechanism of action of antidepressant treatments: Implications for the etiology and treatment of depressive disorders In: Meltzer HY, ed. Psychopharmacology: The third generation of progress. New York : Raven Press, 1987;pp. 535–545.

- Baquiran M, Al Khalili Y. Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Toxicity. [Updated 2021 Jul 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553216

- Ly, C., Greb, A. C., Cameron, L. P., Wong, J. M., Barragan, E. V., Wilson, P. C., Burbach, K. F., Soltanzadeh Zarandi, S., Sood, A., Paddy, M. R., Duim, W. C., Dennis, M. Y., McAllister, A. K., Ori-McKenney, K. M., Gray, J. A., & Olson, D. E. (2018). Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity. Cell reports, 23(11), 3170–3182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022

- Brands, B., Sproule, B., & Marshman, J. 1998. Drugs & Drug Abuse. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation.

- Gasser P, Kirchner K, Passie T. LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: a qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015 Jan;29(1):57-68. doi: 10.1177/0269881114555249

- Gasser, P., Holstein, D., Michel, Y., Doblin, R., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Passie, T., & Brenneisen, R. (2014). Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 202(7), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000113

- LSD Treatment in Persons Suffering From Anxiety Symptoms in Severe Somatic Diseases or in Psychiatric Anxiety Disorders (LSD-assist). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03153579

- Brands et al. 1998. ‘Drugs & Drug Abuse’.

- Krebs TS, Johansen PØ. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2012 Jul;26(7):994-1002. doi: 10.1177/0269881112439253

- Carhart-Harris RL, Kaelen M, Bolstridge M, Williams TM, Williams LT, Underwood R, Feilding A, Nutt DJ. The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Psychol Med. 2016 May;46(7):1379-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002901

- Schmid Y, Enzler F, Gasser P, Grouzmann E, Preller KH, Vollenweider FX, Brenneisen R, Müller F, Borgwardt S, Liechti ME. Acute Effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2015 Oct 15;78(8):544-53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.015

- Thal, S. B., Bright, S. J., Sharbanee, J. M., Wenge, T., & Skeffington, P. M. (2021). Current Perspective on the Therapeutic Preset for Substance-Assisted Psychotherapy. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 617224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617224

- Holland D, Passie T (2011) Flaschback-Phänomene. Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung: Berlin, Germany.

- Baggott MJ, Coyle JR, Erowid E, Erowid F, Robertson LC. Abnormal visual experiences in individuals with histories of hallucinogen use: a Web-based questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011 Mar 1;114(1):61-7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.006

- Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Mar 1;69(2):109-19. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00306-x

- Orsolini, L., Papanti, G. D., De Berardis, D., Guirguis, A., Corkery, J. M., & Schifano, F. (2017). The “Endless Trip” among the NPS Users: Psychopathology and Psychopharmacology in the Hallucinogen-Persisting Perception Disorder. A Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 8, 240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00240

- Halpern JH, Pope HG Jr. Do hallucinogens cause residual neuropsychological toxicity? Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999 Feb 1;53(3):247-56. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00129-x

- Litjens RP, Brunt TM, Alderliefste GJ, Westerink RH. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder and the serotonergic system: a comprehensive review including new MDMA-related clinical cases. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014 Aug;24(8):1309-23. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.05.008

- Halpern JH, Lerner AG, Passie T. A Review of Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) and an Exploratory Study of Subjects Claiming Symptoms of HPPD. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:333-360. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_457

- Berrens Z, Lammers J, White C. Rhabdomyolysis After LSD Ingestion. Psychosomatics. 2010 Jul-Aug;51(4):356-356.e3. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.51.4.356

- Raval MV, Gaba RC, Brown K, Sato KT, Eskandari MK. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in the treatment of extensive LSD-induced lower extremity vasospasm refractory to pharmacologic therapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008 Aug;19(8):1227-30. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.05.008

- Sunness JS. Persistent afterimages (palinopsia) and photophobia in a patient with a history of LSD use. Retina. 2004 Oct;24(5):805. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200410000-00022

- Bernhard MK, Ulrich K. Rezidivierende kortikale Blindheit nach LSD-Einnahme [Recurrent cortical blindness after LSD-intake]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2009 Feb;77(2):102-4. German. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109114

- Strassman RJ. Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. A review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984 Oct;172(10):577-95. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198410000-00001

- Grof S. Realms of the human unconscious: Observations from LSD research. New York : Viking, 1975.

- COHEN S. Lysergic acid diethylamide: side effects and complications. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1960 Jan;130:30-40. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196001000-00005

- Malleson N. Acute adverse reactions to LSD in clinical and experimental use in the United Kingdom. Br J Psychiatry. 1971 Feb;118(543):229-30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.543.229

- Gasser P. Die psycholytische Psychotherapie in der Schweiz von 1988–1993 Eine katamnestische Erhebung. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr 1997;147:59–65.

- Nichols DE, Grob CS. Is LSD toxic? Forensic Sci Int. 2018 Mar;284:141-145. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.01.006

- Klock, J. C., Boerner, U., & Becker, C. E. (1974). Coma, hyperthermia and bleeding associated with massive LSD overdose. A report of eight cases. The Western journal of medicine, 120(3), 183–188. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1129381/pdf/westjmed00307-0025.pdf

- Williams JF, Lundahl LH. Focus on Adolescent Use of Club Drugs and “Other” Substances. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;66(6):1121-1134. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.08.013

- Cohen MM, Marinello MJ, Back N. Chromosomal damage in human leukocytes induced by lysergic acid diethylamide. Science. 1967 Mar 17;155(3768):1417-9. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3768.1417

- Grof S. The effects of LSD on chromosomes, genetic mutation, fetal development and malignancy In: Grof S. LSD psychotherapy. Pomoma , CA : Hunter House, 1980, pp. 320–347.

- Dishotsky NI, Loughman WD, Mogar RE, Lipscomb WR. LSD and genetic damage. Science. 1971 Apr 30;172(3982):431-40. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3982.431

- Smart, R. G., & Bateman, K. (1968). The chromosomal and teratogenic effects of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review of the current literature. Canadian Medical Association journal, 99(16), 805–810. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1945364/pdf/canmedaj01288-0029.pdf

- Robinson JT, Chitham RG, Greenwood RM, Taylor JW. Chromosome aberrations and LSD. A controlled study in 50 psychiatric patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1974 Sep;125(0):238-44. doi: 10.1192/bjp.125.3.238

- Idänpään-Heikkilä JE, Schoolar JC. 14C-lysergide in early pregnancy. Lancet. 1969 Jul 26;2(7613):221. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91466-4

- Auerbach R, Rugowski JA. Lysergic acid diethylamide: effect on embryos. Science. 1967 Sep 15;157(3794):1325-6. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3794.1325

- GREINER T, BURCH NR, EDELBERG R. Psychopathology and psychophysiology of minimal LSD-25 dosage; a preliminary dosage-response spectrum. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1958 Feb;79(2):208-10. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1958.02340020088016

- Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Müller F, Borgwardt S, Liechti ME. LSD Acutely Impairs Fear Recognition and Enhances Emotional Empathy and Sociality. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 Oct;41(11):2638-46. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.82

- Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Steuer AE, Kraemer T, Rentsch KM, Hammann F, Liechti ME. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017 Oct;56(10):1219-1230. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0513-9

- Hysek CM, Simmler LD, Schillinger N, Meyer N, Schmid Y, Donzelli M, Grouzmann E, Liechti ME. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of methylphenidate and MDMA administered alone or in combination. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014 Mar;17(3):371-81. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001132

- Strajhar P, Schmid Y, Liakoni E, Dolder PC, Rentsch KM, Kratschmar DV, Odermatt A, Liechti ME. Acute Effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide on Circulating Steroid Levels in Healthy Subjects. J Neuroendocrinol. 2016 Mar;28(3):12374. doi: 10.1111/jne.12374

- Seibert J, Hysek CM, Penno CA, Schmid Y, Kratschmar DV, Liechti ME, Odermatt A. Acute effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and methylphenidate on circulating steroid levels in healthy subjects. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;100(1):17-25. doi: 10.1159/000364879